Press Release RBI Working Paper Series No. 02

Implications of MGNREGS on Labour Market, Wages and Consumption Expenditure in Kerala

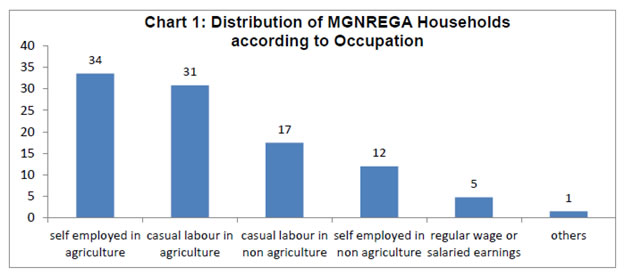

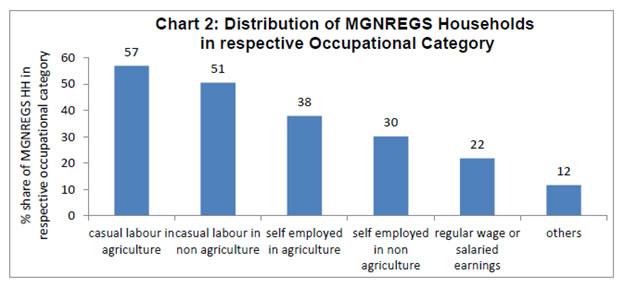

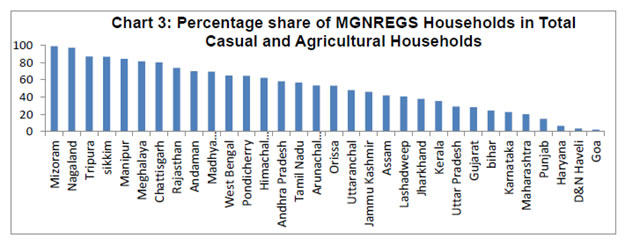

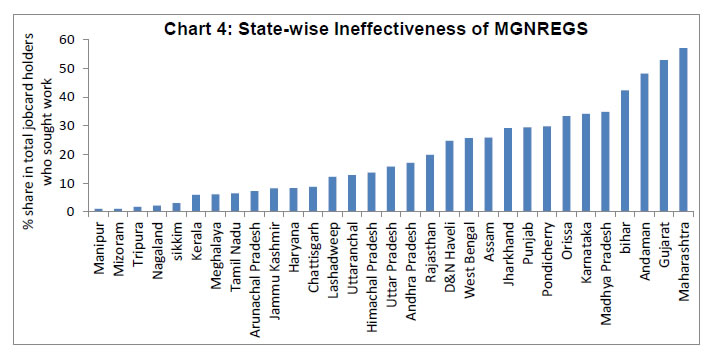

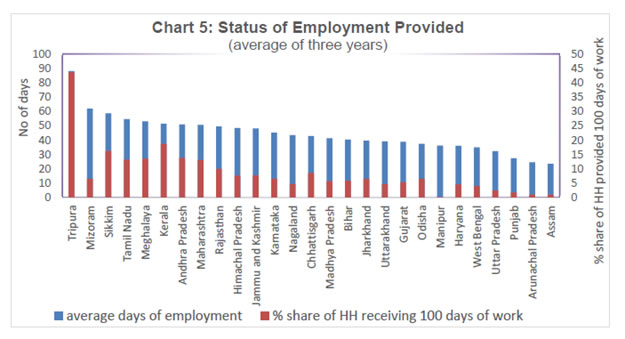

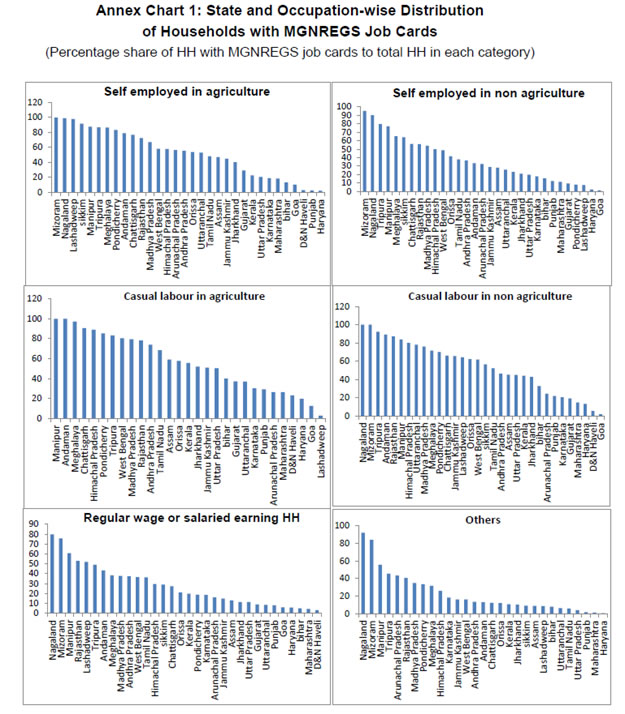

@V. Dhanya Abstract 1This paper makes an attempt to evaluate the implications of MGNREGS in labour short economy of Kerala. The analysis of NSSO unit level data revealed inter-state differences in implementation of the scheme with North-Eastern and Southern states performing better than its counterparts. The primary data analysis showed that MGNREGS has partial impact on labour market and wages in Kerala. It resulted in an increase in wages for certain rural works carried out by female labour force where there was only a marginal difference in wage rates. In general, it provided a fall back option for the rural workers and helped in smoothening consumption during the lean period. An indirect benefit of MGNREGS was improvement in financial inclusiveness and health standards of the workers. The analysis showed that along with implementation of the programme, the implication on labour market depends on initial wage conditions in other sectors. An increase in consumption expenditure, particularly on food items may be viewed as an immediate effect. However, the inflationary effect of this increase in consumption expenditure is limited due to low implementation in majority of states. JEL Classification: J390 J480 H5 R2 Key words: MGNREGS, wages, consumption expenditure, labour market, Kerala Section I: Introduction The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) later renamed as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (henceforth MGNREGA), is an ambitious project of Government of India to bring rural poor out of poverty. The Act was passed in the Parliament in August 2005 and came into effect from February 2006. In the first phase, it was enforced in 200 districts of the country and from April 2008 it is being implemented in all districts in India. “It aims at enhancing livelihood security of the rural households by providing at least one hundred days of guaranteed wage employment in every financial year to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work”2. Work is to be made available to anyone who demands it and is considered a legal right, in the absence of which the State is liable to pay unemployment allowance. MGNREGS is the latest in India’s endeavor to uplift poor from poverty. Unlike the earlier projects, MGNREGS is self-targeting and demand driven thereby giving the people the option of joining the programme. In other words, they can avail MGNREGS when they require it and discard in case of better opportunities. Further, by linking it to the minimum wages in each state, it ensures that minimum wages are paid across jobs making MGNREGS a fall back option thus improving the bargaining power of workers. By assuring 100 days employment, it is a protection against economic insecurity among rural households. The study aims to examine the implications of MGNREGS in a labour short economy like Kerala, in particular, its effect on labour market, wages and in turn on consumption expenditure of rural households. I.2: Methodology Both secondary and primary data is used for this study. Information from MGNREGS site is used for making preliminary analysis. To make detailed assessment of effectiveness of MGNREGS implementation National Sample Survey Organization’s (NSSO) unit level data is used. NSSO’s 66th and 68th round covered some salient features of MGNREGS. Data on employment-unemployment characteristics were collected through Schedule 10 which included questions on participation and demand for work in the MGNREGS. For the rural households information is collected on whether the household had MGNREGS job card and whether worked under the scheme during the last 365 days. The secondary data analysis is supplemented by primary data collected from select panchayats in Kerala. Panchayats are identified based on the performance on employment front and also after discussing with Joint Programme Coordinators of MGNREGS at various districts. As the selection is based on the employment provided, the results of the survey is biased to that extent and cannot be generalised to other areas where the programme is not effectively implemented. The paper is organized in five sections besides this introductory section. Section 2 examines the theoretical underpinnings of the study and also provides a brief literature review. Section 3 looks into various facets of MGNREGS Act and its implementation in various States and in particular in the study area. It also uses NSSO unit level data to analyse the effectiveness of implementation of MGNREGS in various states. The results of primary survey are examined in Section 4. Section 5 concludes the paper. Section 2: Literature Review The idea of government as employment guarantor is not a new one; it dates back to 17th century (Kaboub, 2007). The origins of Employment Guarantee Scheme (EGS) can be traced back to the 1817 Poor Employment Act and the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act in Great Britain (Basu et al, 2009). Later on, the New Deal programs of the 1930s in the United States received worldwide attention as a way out of high unemployment in the US economy. Further counter-cyclical public works programmes were introduced during the milder recessions around 1950-75 (Lipton 1996). Lipton (1996) points out that the nature of poverty in western countries made the programs successful in these countries while the difference in conditions limits its applicability in developing countries. According to him residual poverty in the West in the 1930s and 1960s was not due to the absence of skills or other assets in the workforce. Such poverty was, perhaps, substantially due to cyclical constraints on the demand for labour. The public works programmes addressed these temporary mismatches and helped to justify a policy of balancing the budget only over the business cycle, i.e. with substantial deficits to finance public-works employment in recessions, and offsetting surpluses to contain inflation in booms. On the other hand, employment guarantee schemes may not enable permanent escape from poverty as is experienced by developing countries, unless accompanied by special measures such that the works programme itself builds up assets (savings, physical capital, skills, health or infrastructure) owned by, or providing future employment income to, the poor. However, it is to be noted that many developing countries have resorted to public works programmes for increasing income and consumption, for reducing poverty or for infrastructure development or a combination of the three (Ninno et al, 2009). Public works programs are increasingly used in low and middle-income countries to achieve the dual purposes of providing a safety net for the poor while improving infrastructure to promote long-term growth (Bose 2013). A notable aspect of these programs, apart from their common stated objective of poverty reduction, lies in the specific limits they impose on reach and accessibility (Basu, 2009). This was achieved through targeted transfers to the poor through various workfare programs (Dreze and Sen, 1991). Within the targeted population, it mostly works in the principle of self-selection. For example, Tanzania's Special Public Works Programs (1978) was instituted within village limits, with employment guarantee limited only to residents. Similarly, Government of Argentina introduced ‘Trabajar’ in 1996 which continued till 2002 whereby wages were provided to beneficiaries in return for their work on small infrastructure projects proposed by local governments and NGOs. The food-for-work (FFW) program and the Rural Maintenance Program (RMP) of Bangladesh are another two examples of Government directly providing employment. The FFW program has been operating in Bangladesh since 1975 and aimed to create food-wage employment during the slack season, mostly in construction and maintenance of rural roads, river embankments and irrigation channels. Wage payments were made in kind (that is, in wheat) rather than in cash. Such a practice was thought to stabilize food grain prices in the market and improve food consumption and nutrition of the participating households (Ahmed et al, 1995). It is pointed out that employment guarantee programmes can induce positive labor market responses by improving the bargaining strength of workers (Drèze and Sen 1991; Dev, 1995). By bringing competition to local labor markets, employment guarantee schemes can help the development of markets where this is most needed (Zepeda E and DAlarcón, 2010). Various studies have examined the implication of MGNREGS on India’s labour market, particularly its effect on women labour force and wages. Imbert and Papp (2012), using a difference-in-difference approach, found that it increases employment by 0.3 days and private sector casual wage by 4.5 per cent. Azam (2012) points out that MGNREGS has not increased the wage rate in general; on the other hand, what it did was reduction in the gender wage gaps in casual works by increasing the wages of female casual worker. However, Zimmermann (2012) finds no effect on employment and only a small increase in private sector wage for women using regression discontinuity method. Dutta et al (2012) found that scheme is reaching the rural poor and backward classes and is attracting poor women into the workforce. Khera and Nayak (2009) reported that women have benefitted through better access to local employment, at minimum wages, with relatively decent and safe work conditions. MGNREGS has also widened the choice set for women by giving them independent income-earning opportunity. It has empowered the women of rural areas providing them decision making ability and also participating in Grama sabhas (Das, 2013). Another group of studies have examined MGNREGS’s impact on poverty and consumption expenditure. Klonner and Oldiges (2013) found MGNREGS to improve ';social protection and livelihood security'; for a particularly disadvantaged group of the rural population. IAMR (2008) evaluation study on MGNREGS found that there is an increase in spending on food and non-food items. Ravi and Englar (2009) by using survey data collected at two time periods found that MGNREGS significantly increased expenditure on food by 40 per cent and non-food consumables by 69 per cent. They also found that the program improved the probability of holding saving by 9 per cent. Significant impact on calorie consumption, protein intake and consumption expenditure was found by Liu and Deininger (2010) who used a panel data for 2500 households from five districts in Andhra Pradesh, during three separate time periods. The present study is an addition to the existing gamut of literature by looking from a regional perspective. Section 3: MGNREGS and its Implementation Across States 3.1: Status of MGNREGS in India and Kerala MGNREGS aims at enhancing livelihood security of the rural households by providing at least one hundred days of guaranteed wage employment in every financial year to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work. An overview of the performance of MGNREGS in the last few years is given in Table 1. As of now MGNREGS is implemented in more than 96 per cent of the districts in the country. In 2013-14, it had provided employment to 48 million households in rural areas. Women workers benefitted most from the scheme accounting for nearly 50 per cent of workforce at all-India level and 93 per cent in Kerala. | Table 1: Overview of MGNREGS - Kerala and All-India | | (No. in million) | | | All-India | Kerala | | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | | Coverage in district | 635.0 | 636.0 | 644.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | | No. of HH provided employment | 51.0 | 50.0 | 47.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | | No. of person days generated | 2188.0 | 2305.0 | 2177.0 | 63.3 | 83.8 | 86.5 | | SCs person days | 485.0 | 512.0 | 493.0 | 10.0 | 13.0 | 13.5 | | Percentage share | 22.9 | 23.4 | 25.7 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 15.6 | | STs person days | 409.0 | 410.0 | 372.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.3 | | Percentage share | 19.3 | 18.8 | 19.4 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 2.9 | | Women person days | 1019.8 | 1138.9 | 1025.6 | 59.0 | 78.0 | 80.8 | | Percentage share | 48.2 | 52.1 | 53.5 | 92.9 | 93.0 | 93.4 | | Average days of employment provided per HH | 43.2 | 46.2 | 45.8 | 44.7 | 54.9 | 56.8 | | % of HH completing 100 days | 7.8 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 22.3 | 24.2 | | Source: http://nrega.nic.in/ | While MGNREGS is introduced in 96 per cent of districts in India, it does not automatically ensure full implementation. As against the stipulated 100 days of employment per household, only less than 10 per cent are given 100 days of employment at the all-India level. On the other hand, in Kerala, more than 20 per cent of households have received the 100 days of employment during 2012-13 and 2013-14. Thus, even though it is introduced in majority of districts, its implementation differs across states and districts. Accordingly, the effect of MGNREGS will also be different based on the level of implementation. The data given in MGNREGS site relates only to MGNREGS households. However, for analyzing the effectiveness of the programme, wider details are required including the number of rural households in each state and their occupational and income classification as MGNREGS is targeted more on the casual labour category. Hence, for investigating the effectiveness of the programme, NSSO unit level data is analysed. 3.2: Effectiveness of MGNREGS - A State-wise Analysis In this sub section, NSSO unit level data on Employment and Unemployment Survey (68th Round) is examined for measuring effectiveness of MGNREGS3. The data pertains to the time period July 2011 to June 2012. As pointed out in Section 1, Schedule 10 of the Survey includes questions on MGNREGS like whether the household has got MGNREGS card and whether worked in MGNREGS during the last 365 days. Using these data the effectiveness of MGNREGS in each state is examined. Effectiveness can be analyzed at two levels; (1) in terms of number of households (HH) having MGNREGS job card and (2) whether the HH having job card have actually got work. While the former measures effectiveness in coverage, the latter measure effectiveness in implementation. Thus, in this scheme effectiveness of the scheme is looked at the limited perspective of providing job card as well as employment. Hence, issues like quality of work and asset created is outside the purview of this study. A state can be ineffective at the first level itself whereby only a limited number are offered job card. By its design MGNREGS is more applicable to casual labour and agriculture income household where income flow is not continuous. Within the agricultural income households, it is more applicable to small and medium farmers and hence analysis is made after eliminating households having land above 5 hectares. Our analysis on NSSO data supports the above assumption and reveals that majority of MGNREGS households belongs to casual labour households and agricultural households (Chart 1).  Similarly, more than half of the casual labour households in India have got MGNREGS job card (Chart 2). For example 57 per cent of casual labour in agriculture and 51 per cent of casual labour in non-agriculture households have MGNREGS job card. While their share is higher than the other categories, it throws light to fact that almost half of the casual labour households have still not even applied for job card. While there may be some element of voluntary exclusion in this, it underlines the need of increasing its coverage. Further, there may be inter-state disparities in implementation of the scheme which also needs to be addressed.  A state-wise analysis of MGNREGS implementation reveals wide difference in the coverage of MGNREGS (Chart 3). In general, North Eastern states, Chhattisgarh, Uttaranchal, Rajasthan, Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh, were more effective in providing MGNREGS job card. On the other hand, Haryana, Punjab and Maharashtra are the worst performers among the major states. Among the various occupational categories, casual labour households were having more MGNREGS job card holders compared to other job categories (Annex Chart 1).  The above analysis shows that there is wide differences in coverage of MGNREGA across states. Next, the status of implementation of MGNREGA across States is looked at. As pointed out above, a state can be effective in implementing MGNREGS only if they could provide job for those who have sought work. For analyzing this, the individuals who have registered for the MGNREGS job card is first identified and then examined their job status. Under job status the data provides three alternatives, viz, (1) worked under MGNREGS (2) sought but did not get work and (3) did not seek work. Among the three categories only the second can be taken as signal of ineffectiveness as the third is voluntary in nature. If at least one individual in a household have received job under the scheme, then that household is treated as covered. Accordingly, Chart 4 provides the state-wise ineffectiveness.  Maharashtra ranks top in ineffectiveness measured in terms of percentage share of individuals who have sought but did not get work to total number of individuals having job card. Among the households with MGNREGS job card, 57 per cent have sought work under MGNREGS and were not able to get work in Maharashtra. On the other hand, North Eastern states and Southern States like Kerala and Tamil Nadu were more effective in providing work for those having job card. Taken together, it can be concluded that North Eastern states and Chhattisgarh are the most effective in implementing MGNREGS in both counts. States like Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Jammu Kashmir also performed well in terms of providing job for the job card holders, though in coverage their performance is low. Haryana, on the other hand, though came in the top group in terms of work provided, performed dismally when the coverage was considered. Out of the total rural household with land below 5 hectares and also excluding the regular salaried and wage class, Haryana could provide job card only for a meager 7 per cent. Hence, even though it came top in terms of job provided, it cannot be considered as a high performer. On the other hand, Maharashtra, Bihar, Gujarat and Karnataka were the worst performers in both counts (Table 2). | Table 2: Effectiveness of Implementation of MGNREGS across States | | Share of individuals who have sought work but not provided work among the job card holders (%) | States | Share of job card holders among

rural HH excluding regular salaried/ wage earners (%) | States | | 1-10 | Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, Nagaland, Sikkim, Kerala, Meghalaya, Tamil Nadu, Arunachal Pradesh, Jammu Kashmir, Haryana, Chhattisgarh | More than 80 | Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, Sikkim, Manipur, Meghalaya, Chhattisgarh | | 10-20 | Uttaranchal, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan | 60-80 | Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Himachal Pradesh | | 20-30 | West Bengal, Assam, Jharkhand, Punjab | 40-60 | Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Arunachal Pradesh, Odisha, Uttaranchal, Jammu Kashmir, Assam | | 30-40 | Odisha, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh | 20-40 | Jharkhand, Kerala, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Bihar, Karnataka, Maharashtra | | 40-60 | Bihar, Gujarat, Maharashtra | less than 20 | Punjab, Haryana | | Source: Calculated from NSSO 68th Round data | NSSO data does not provide data on the number of days the individual has worked under the scheme and hence if the person is provided work even for a single day, then the household to which he belongs is considered to be a provided work. Accordingly, even if the state is providing work only for a few number of days per household, then also, as per the above analysis, it is considered to be effective if large number of households are provided work. To overcome this, average days of employment and percentage share of Household worked for 100 days are looked at for each state in Chart 5. The data taken is the average figure for the last there years, i.e. 2012-13 to 2014-15.  In case of providing 100 days of work, with the exception of Tripura, other states performed miserably during the last three years. Tripura provided 100 days of work for 44 per cent of Households coming under the scheme. Tripura also came highest with average number of man days at 88 days. North Eastern states like Mizoram, Sikkim and Meghalaya also performed well though Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur came at the lower end. In providing 100 days of work also these states performed dismally with 1.0 and 0.2 per cent, respectively. Among other States, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh performed relatively better than its counterparts and in general the results are in sync with the analysis of NSSO data. The major exception is Maharashtra which performed well compared to other least effective states as per NSSO data analysis. Thus, the analysis in this section shows that there is inter-state difference in implementation of MGNREGS with North Eastern and Southern States performing better than others. Because of this inter-state differences in implementation of the scheme, the implication of it will also be different in different states. Accordingly, it is meaningful to take the case of states separately while looking at the effect of MGNREGS. In the next section, status and implications of MGNREGS in Kerala is looked at by analysing the primary survey data. Section 4: Results of Primary Survey Kerala is faced with an unusual scenario whereby high unemployment rate co-exists with labour shortage. As per NSSO 2011-12 data, unemployment in Kerala as per usual status (adjusted) was 6.8 per cent in rural areas and 6.1 per cent in urban areas as against the all-India average of 1.7 and 3.4 per cent, respectively. On the other hand, Kerala faces shortage of manual labour, which is closely linked with Keralites migration to Gulf region. Majority of migrants to Gulf countries belonged to the casual labour category resulting in their shortage in the homeland. Further, the ensued inflow of foreign remittances resulted in construction boom in the economy which increased the demand of casual labour. This combined with labour shortage pushed up the labour cost. Further, the reluctance for manual labour among the educated youth also resulted in shortage in this category. The demand supply mismatch is evident from the high wages prevalent in Kerala when compared to other States. The higher wages attracted labourers from other states. At present, demand for casual labourers is often met by hiring migrant labourers even in villages of Kerala. In normal circumstance, MGNREGS is redundant in such an economy as demand for labour already exists and thus invalidates the need for a government programme providing employment. This may be one reason for the low percentage of job card applicants in Kerala as is evident from the NSSO data. At the same time, the analysis on effectiveness of implementation shows that Kerala is one of the state in which it is effectively implemented. Only 6 per cent of individuals did not get a job even after seeking it making it a high performer in implementing the programme. This means that the programme is indeed utilized in Kerala and hence is worthwhile to examine its implication. The question addressed in this context are (i) whether MGNREGS resulted in further shortage in supply of labour and resulted in an increase in wages. (ii) Whether it has increased consumption or helped in smoothening consumption among the MGNREGS households. 4.1: Profile of Survey Area A primary survey was conducted among the select panchayats in Kerala, chosen based on employment provided under MGNREGS. The panchayats which have given maximum employment is considered for primary survey. However, large panchayats have a natural advantage due to its population size, to avoid that the final selections are made after discussing with Joint Programme Coordinators of MGNREGS at various districts. Accordingly, the ten panchayats from four districts are selected for the survey, the details of which are given in Table 3. | Table 3: Indicators of MGNREGS in Survey Areas | | Districts | Panchayats | No. of HH demand-ing job cards

(‘000s) | Percentage Share | | HH issued job card among HH applied | HH demanded work among job card holders | HH alloted work among work demanded | HH worked among HH alloted work | HH completed 100 days | | Alappuzha | Mararikulam | 6.5 | 99.9 | 74.4 | 100.0 | 93.7 | 41.9 | | Alappuzha | Muhamma | 3.0 | 100.0 | 64.5 | 100.0 | 96.6 | 57.5 | | Alappuzha | Arattupuzha | 5.8 | 99.7 | 81.6 | 100.0 | 96.7 | 56.2 | | Idukki | Adimaly | 7.5 | 99.9 | 82.7 | 100.0 | 96.4 | 34.7 | | Idukki | Konnathady | 6.0 | 99.2 | 91.5 | 100.0 | 96.7 | 21.9 | | Thiruvananthap’m | Chenkal | 7.3 | 100.0 | 76.3 | 100.0 | 78.8 | 80.4 | | Thiruvananthap’m | Vellarada | 6.6 | 99.8 | 85.1 | 100.0 | 96.9 | 63.2 | | Wayanad | Mananthavady | 6.5 | 97.4 | 81.4 | 100.0 | 93.8 | 15.6 | | Wayanad | Vellamunda | 6.9 | 99.4 | 75.4 | 100.0 | 88.0 | 6.7 | | Wayanad | Poothadi | 6.7 | 99.9 | 85.7 | 100.0 | 96.3 | 20.3 | | Total of Panchayats | 62.7 | 99.5 | 80.6 | 100.0 | 93.2 | 38.3 | | Kerala | 2,844 | 99.4 | 59.4 | 100.0 | 90.8 | 26.7 | | India | 134,627 | 98.7 | 39.8 | 99.9 | 92.8 | 9.5 | | Source: http://mnregaweb4.nic.in/ | The various indictors show that the selected panchayats were relatively better in terms of performance when compared with Kerala and all-India level. In fact, the data shows that job card was issued almost to all those who have applied for job card. However, when compared to Kerala only less than half of the job card holders have demanded work at the all India level. In all the selected panchayat the demand pattern was higher than the Kerala average with Konnathadi panchayat of Idukki district having a demand ratio of 91 per cent. With the exceptions of panchayats in Wayanad and Idukki, other panchayats had higher percentage of households completing 100 days. Thus, in terms of various indicators, these panchayats are better performers, validating their selection for analyzing the implications of MGNREGS. Panchayats in Idukki and Wayanad districts have hilly terrain and are oriented towards plantation crops, specifically coffee, pepper and cardamom. Hence, occupations of low income households are centered on plantations involving pre-harvesting, harvesting and post-harvesting operations. Dairy farming is another occupation followed by households and is often managed with other jobs. Agriculture in panchayats in Thiruvananthapuram district are centered around paddy, rubber and vegetables. The occupation of panchayats of Alappuzha district is centered on paddy farming, fishing and coir industry. As other parts of Kerala, these regions have high literacy rate. All panchayats have at least one bank in their area. The socio-economic characteristics of the villages selected are given in table 4 | Table 4: Socio-economic Characteristics of Selected Panchayats | | No. | Panchayat | District | Major occupation of low income groups | Literacy rate

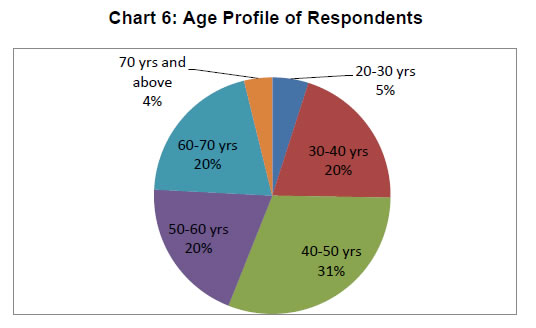

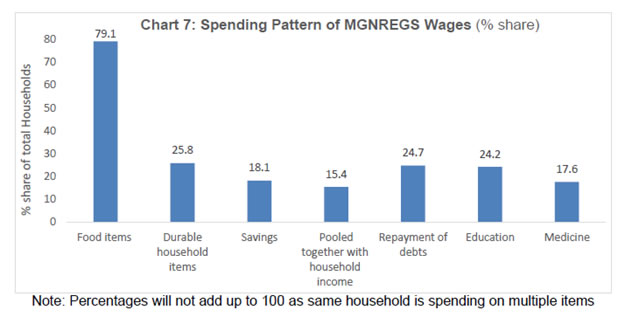

(2001 census) | | 1 | Adimali | Idukki | Plantation crops - Coffee, pepper; plantain | 83 | | 2 | Konnathadi | plantation crops - coffee, pepper | 94 | | 3 | Poothadi | Wayanad | Plantation Crops - Coffee, Cardamom, pepper | 85 | | 4 | Vellamunda | Plantation crops, Plantain cultivation, Arecanut | 82 | | 5 | Mananthavadi | Plantation crops, Plantain cultivation, Arecanut | 86 | | 6 | Vellarada | Thiruvananthapuram | rubber, paddy, vegetables | 83 | | 7 | Chenkal | Paddy, plantain, rubber, cassava, vegetables; small industries | 87 | | 8 | Arattupuzha | Alappuzha | Fishing, coir | 92 | | 9 | Muhamma | coir, fishing, paddy, plantain, vegetables | 94 | | 10 | Mararikkulam | coir, paddy, plantain, vegetables | 94 | Survey was conducted in 10 panchayats of 4 districts covering 182 NREGA workers. Nearly half of the respondents belonged to BPL category. About 62.4 per cent of respondents have studied only up to 10th standard. Out of the 68 respondents who have 10th and above education, two were graduates. The income category along with the educational profile of respondents showed that MGNREGS is preferred mostly by low income unskilled category. Most respondents fall under the age group of 40 to 50 years (Chart 6). In sync with state as well as national profile of MGNREGS workers, 93 per cent of respondents in the survey were women. Of the 7 per cent of the male respondents, 55 per cent belonged to the age category of 50 to 70 years. With the exception of one, all of them were farmers. Under MGNREGS scheme, lands of only those households having job card are attended to and the members of household needs to be part of the work. Hence, the male occupants of the households who are primarily into farming also participate in MGNREGS work to take benefit of the scheme.  The profile of respondents shows that they are in sync with the state level workers’ profile. Further, the indicators on performance position these panchayats ahead of state average. In the next sub section the implications of MGNREGS in these panchayats are examined. 4.2: Effects of MGNREGS Effect on Labour Market and Wages In a labour short economy like Kerala, the major factor that determines the implication on labour market is the type of workforce joining the scheme are - they new entrants or are they shifting from other occupations. The survey results give a mixed picture where by 57 per cent of respondents were working in some other sector earlier. Some have shifted due to low job opportunities at their respective occupational category. For example, nearly 43 per cent of respondents in the selected panchayats of Alappuzha district were coir workers prior to joining MGNREGS. They have shifted to MGNREGS due to lack of availability of coir fibre, the raw material for making coir yarn, at regular periods. Many of them combine coir braiding with MGNREGS work, whereby they take up coir work as and when coir fibre is available. Similar was the case of those who were engaged in seasonal jobs like fishing or agriculture. This does not strictly qualify for being called as ‘substitution’ as they did not give up their primary job for MGNREGS work. More than half of the respondents who were engaged in other works prior to MGNREGS responded of combining both works after becoming a member of the scheme. Hence, in most cases, it did not result in a shortage of labour, alternatively, the programme offered a fall back option to the workers in the event of non-availability of work in their regular sector. However, situation is different in the case of new workers who hitherto were not in labour force due to one reason or another. Nearly 43 per cent of respondents were new labourers and majority confines themselves as MGNREGS worker. Previously, many women, though belonging to the low income group were not willing to work, either due to absence of suitable employment or social stigma associated with manual labour. However, MGNREGS through its group labour and government tag succeeded in doing away with this social stigma. Further, the guidelines to provide work within 5 km of their residence4 also attracted women to come forward. However, majority of new entrants are not forming a part of labour force and are not willing to do manual labour outside MGNREGS. Only two have responded that MGNREGS helped them in learning new skills and are going for alternate employment. Thus, the programme has limited effect on labour market in terms of substitution between works as well as adding to the labour force in general. The high wages prevalent in alternative works acts as a disincentive for substituting with MGNREGS. Nevertheless, it has increased wages in certain segments of work, particularly; the women centric work in coffee and cashew producing areas. Wages have increased for women agricultural labourers in Wayanad and Idukki who were getting marginally higher wages than the MGNREGS work. Compared to the latter, the work intensity is higher as agricultural workers and the wage gap were also small. Along with this the 100 days of guaranteed work made MGNREGS the preferred one over the traditional job. As a result, the farm owners were compelled to offer higher wages for employing women agricultural labourers for harvesting and post harvesting operations. This is particularly so in plantation where women are involved in cleaning coffee plantation as part of pre-harvest operations, plucking of coffee and collecting cashew kernels in cashew plantations. Another stream of work affected is the household maids. These jobs generally done by women are facing severe challenge from MGNREGS works and very often owners are forced to pay higher wages. However, as pointed out earlier, wage increase cannot be generalized across all works. It depends to a large extent on the nature of the work as well as the regularity of work offered. Similar results were arrived at by Azam (2012) who analysed the implication of MGNREGS at the national level. Effect on Agriculture MGNREGS to an extent had mitigated the negative effect of high labour cost on agriculture in Kerala. MGNREGS work has offered a respite to the higher labour cost by allowing agricultural operations in the private land on the condition of owners also being MGNREGS member. According to the respondents, many have come forward for paddy farming and vegetable cultivation even by taking land on lease. MGNREGS and Women Empowerment MGNREGS has brought women to the forefront of decision making both within family and also in social circles. About 92 per cent of MGNREGS beneficiaries in Kerala are women as opposed to 55 per cent at all-India level (Table 1). Our survey results were also representative of state phenomenon whereby out of the total 182 persons surveyed 93 per cent were women. Women empowerment through MGNREGS in Kerala needs to be looked at together with the much discussed SHG movement in Kerala. Almost 90 per cent of women MGNREGS workers interviewed were part of Kudumbashree or other SHGs. These organisations which are bank-linked, through weekly saving (thrift) and small loans, already have familiarised women in handling financial matters. By being part of the scheme, they have got a means of income and together with the financial support offered by SHGs in times of need, they have become part of financial decision making in the family. Further, it also enhanced their credit worthiness. Majority opined that being an MGNREGS worker has enhanced their capacity to borrow as lenders are sure of getting back the money. Thus, being an MGNREGS member itself acts as a security for getting loans from friends and neighbours. In a way, both the institutions together have helped the poor to smoothen the consumption gaps. Implications on Poverty MGNREGSs implication on poverty is directly reflected in providing income during offseason by offering work and indirectly by enhancing the capacity to borrow, as mentioned earlier. In both ways, MGNREGS helps smoothening consumption over the lean period. This was particularly true for agricultural labourers and also fishermen community whose income is seasonal. Further, by bringing women which were hitherto not in workforce, MGNREGS has increased the income of household. Majority opined that MGNREGS has improved their living standards and income. Discussions with the village heads and villagers also pointed to the fact that MGNREGS has helped in reducing abject poverty. Those who are able and willing to do work could get work under the scheme, thus providing an avenue for income. MGNREGS and Consumption Expenditure The survey showed that MGNREGS has positively affected the consumption expenditure of households. The data collected is for a particular point of time and hence could not be compared with any other period. Nevertheless, by asking the respondents their view on their standard of living and consumption pattern, a subjective view on their improvements can be reached. Nearly 90 per cent opined that MGNREGS have improved their living standards, while 79 per cent replied of spending on food items using MGNREGS wages directly increasing the demand for these products (Chart 7). In particular, the respondents have pointed that consumption of fruits and dairy products has increased.  In most cases, the MGNREGS income is an extra income for the household. As pointed above, nearly half of the workers are new entrants to the labour market whose income adds to the total income of the household. Even in cases of alternative employment, the MGNREGS wages helps smoothening consumption by ensuring steady flow of income even in the lean period. This has reduced absolute poverty in rural areas and also improved consumption expenditure. Indirect Benefits of MGNREGS One of the indirect effects of MGNREGS is the improvement in financial inclusion. By making the payments of wages through banks or post office account, MGNREGS promoted usage of banks among the poorer section. It promoted financial inclusion among the lower strata of the society and particularly, among women who forms 95 per cent of MNREGA workers. Nearly 75 per cent of the respondents opened bank account after being a member of MGNREGS. Another indirect effect is the improvement in health standards of the people involved. The new entrants who were otherwise sedentary opined about the improved health after joining the programme. The incidence of life style diseases associated with sedentary routine has come down. Villagers and panchayat officials have also pointed out about the improvement in general cleanliness. Most of the works undertaken in Kerala are cleaning of waterways, ponds, public place etc which hitherto were neglected leading to contagious diseases. With the taking up of public work, this also has come down. However, detailed health study is required for corroborating this at a larger level and is not a focus of our study. Section 5: Summary and Conclusion 5.1: Major Findings of the Study This paper was an attempt to evaluate the implications of MGNREGS in labour short economy. In particular, the study evaluated its effect on the rural labour market, wages and also on the consumption habits of rural workers. The analysis of NSSO data showed that Kerala performed well in terms of implementation of MGNREGS though its coverage was limited. MGNREGS was able to attract only 29 per cent of casual and self-employed households. However, such low percentage cannot be construed as a failure of MGNREGS as this has more to do with finding better opportunities outside the programme than due to lack of awareness of the programme. Further, Kerala could provide job for 95 per cent of workers that sought work under MGNREGS making it one of the most effective states in implementation. Using primary data, the study found that MGNREGS has partial impact on labour market and wages, though it has improved the consumption expenditure of rural households. MGNREGS has resulted in shortage of women labour force involved in pre and post harvesting operations in agrarian districts of Wayanad and Idukki. Further, shortage of household maids has also increased after the implementation of the programme. As a result, wages for women labour force involved in this work has increased, which was earlier only marginally higher than the MGNREGS wages. However, this was limited to only certain types of work and cannot be generalized across works and regions. Nearly half of MGNREGS workers are new entrants to the labour force and are confined to the MGNREGS works only resulting in limited impact on the labour market and wages. Further, many of the works carried out by them like weeding, preparing land for agriculture were already faced by severe labour crunch and was hence left unattended in many areas. Hence, there was only limited conflict of interest between MGNREGS workers and already existing workers. One positive effect of MGNREGS is that it helped in smoothening consumption for the workers engaged in seasonal employment like agriculture and fishing. It gave them opportunity to work under MGNREGS when traditional employment is lacking. Over all, MGNREGS was found to have positive impact on consumption whereby consumption of food products and dairy products have increased for the MGNREGS workers. The payment of MGNREGS wages were made through bank accounts or post office accounts with former accounting for the major share. While this avoids the leakages, it has thrown light to the need for familiarizing the people with the use of ATMs and other technology induced banking services. Banking correspondent model may be used for providing wages to MGNREGS workers as this would help the people as well as the banks in providing better service. MGNREGS along with SHGs have made rural people less dependent on money lenders. The goal of MGNREGS is to provide livelihood security for the poor through the creation of durable assets, improved water security, soil conservation and higher land productivity. Most of the works carried out in Kerala are in the nature of soil conservation and cleaning of water-ways. The regular cleaning carried out by MGNREGS workers has improved the environment thereby improving the health status of the rural people. 5.2: Conclusion While the productivity of labour engaged in MGNREGS work is still a question, there is no doubt on its implications on livelihood security of the poor. It has provided a fall back option for the rural workers, thus providing security against unemployment and poverty in the lean period. However, providing more work days may lead people to consider MGNREGS as the main job rather than the supplementary job as it has been originally conceived. Needless to say, majority of the respondents wanted MGNREGS to increase its person days. However, this may result in severe shortage of labour in certain sectors as more and more labourers will be attracted to the programme unless the wages of competing sectors are hiked which will have implications on inflationary situation in the country. Thus, the programme which was envisaged as a counter cyclical measure will turn to a cyclical measure adding to inflationary pressures in the economy. The NSSO data showed that in most poverty stricken states, the coverage as well as implementation of MGNREGS is dismal. Efforts should be made at the state as well as panchayat level to make it effective. The objective of development planning ever since independence was to bring people out of poverty. By providing fall back option and payment of wages through bank and post office accounts, MGNREGS could bring more and more rural households out of poverty. A natural effect of this will be an increase in consumption expenditure, particularly, on food items as the marginal propencity to consume of poor is quite high. Given that the demand for these is higher than its supply, an increase in consumption expenditure will automatically increase the inflation pressures in the economy. Thus, MGNREGS has got its defects - it is not properly implemented in all states, the asset creation and quality of work may be dismal and it might be a contributing factor to the persistent inflationary situation in the country given its influence on consumption expenditure. However, withdrawing the programme may not be an ideal policy measure as MGNREGS has the potential to bring down rural poverty drastically. What is required is coordinated thinking and action on the part of implementing panchayats to use it as a productive weapon and minimizing its negative impacts. The panchayats can identify the potential of the region and also the supply shortages in agriculture and allied subjects. It could introduce the work during the lean season so that its effect on other works is minimal. Panchayats may come up with a plan document which elaborates the potential and shortages in their respective region and identify ways to improve the condition by using MGNREGS labour force. Incentive in terms of additional funding can be provided to the best performing panchayats both in terms of implementation as well as in terms of assets created (weightage should be given to self-sustaining durable assets) by comparing the results with the original agenda. For achieving this, states should be given considerable leeway in deciding what is permissible under MGNREGS and what comes under negative list. The guidelines for 2013 has included normal agricultural operations such as land preparation, ploughing, sowing, weed removal, turning the soil, watering, harvesting, pruning and such similar operations under negative list. MGNREGS was able to bring vibrancy in Kerala’s agricultural scenario particularly in paddy and vegetable farming. But the inclusion of agricultural operations in the negative list had a detrimental effect on Kerala, which depends on other states for nearly 75 percentage of its consumption needs. However, this may not be true for other states. A one size fits all approach may not be viable while formulating the guidelines as states and regions vary widely in agricultural and economic situations. Hence, the programme could perform better if states are given freedom to decide on the permissible and non-permissible list. At the same time, Centre should decide on the broad indicators like wages and number of person days to be provided employment and also the indicators to measure the efficiency of the programme. Overall the future of MGNREGS depends on how effectively it is implemented across the regions without transforming itself to a pro-cyclical measure.

References Ahmed A U., Z. Sajjid, K. K. Shubh and H. C. Omar (1995), ‘Bangladesh’s Food for Work Programme and Alternatives to Improve Food Security’, in Jaochim von Braun (ed) Employment for Poverty Reduction and Food Security, Washington, D.C, International Food Policy Research Institute. Azam, Mehtabul (2012), ‘The Impact of Indian Job Guarantee Scheme on Labour Market Outcomes: Evidence from a Natural Experiment’, IZA Discussion Paper No.6548. Basu, A K, Chau N H, Kanbur R. (2009), ‘A Theory of Employment Guarantees: Contestability, Credibility and Distributional Concerns’, Journal of Public Economics, 93:482–497. Bose, Nayana (2013), ‘Raising Consumption through India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme’, October, available at https://my.vanderbilt.edu/nayanabose/files/2013/11/Job-Market-Paper_Nayana-Bose.pdf. Das, S. K. (2013), Employment for Poverty Reduction and Food Security ‘A Brief Scanning on Performance of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in Assam, India’, American Journal of Rural Development, 1(3): 49-61. Dev, S. Mahendra (1995), ‘India’s (Maharashtra) Employment Guarantee Scheme: Lessons from Long Experience’, in Joachim von Braun (ed.), Employment for Poverty Reduction and Food Security, pp. 108–143, Washington D.C, International Food Policy Research Institute. Drèze, Jean, Sen, Amartya (1991), ‘Strategies of entitlement protection in Hunger and Public Action’, Clarendon press, Oxford. Dutta, P., R. Murgai, M. Ravallion, and D. Van de Walle (2012), ‘Does India’s employment guarantee scheme guarantee employment?’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No.6003. IAMR, (2008), ‘All-India Report on Evaluation of NREGA: A survey of twenty districts’, New Delhi: Institute of Applied Manpower Research. Imbert, Clement and Papp, John (2012), ‘Labor Market Effects of Social Programmes: Evidence from India’s Employment Guarantee’, CSAE Working Paper, 2013-03. Kaboub, Fadhel (2007), ‘Employment guarantee programs: a survey of theories and policy experiences’, Levy Economics Institute Working paper No 498. Khera R and Nayak, N (2009), ‘Women workers and perceptions of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act’, Economic and Political Weekly, 44(43), 24-30 October, pp. 49-57. Klonner, S and Oldiges, C, (2013), ‘Can an Employment Guarantee Alleviate Poverty? Evidence from India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act’, Draft paper, University of Heidelberg. Lipton, Michael (1996), ‘Successes in anti-poverty, Issues in Development’, ILO Discussion Paper 8. Liu Yanyan and Klaus Deininger (2010), ‘Poverty Impacts of India's National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme: Evidence from Andhra Pradesh’, Paper presented at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association 2010, AAEA, CAES, & WAEA Joint Annual Meeting, Denver, Colorado, July 25-27, http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/62185/2/Paper_NREGA.pdf. Ninno Carlo del, K Subbarao and A Milazzo (2009), ‘How to Make Public Works Work: A Review of the Experiences’, World Bank SP Discussion Paper No 0905. Ravi, S., and M. Engler (2009), ‘Workfare in Low income Countries: An effective Way to Fight Poverty? The Case of NREGS in India’, available at http://www.isid.ac.in/~pu/conference/dec_09_conf/Papers/ShamikaRavi.pdf Zepeda E and DAlarcón (2010), ‘Employment Guarantee and Conditional Cash Transfers Programs for Poverty Reduction’, available at http://www.chronicpoverty.org/uploads/publication_files/zepeda_alarcon_cash_transfers.pdf Zimmermann, Laura (2012), ‘Labor Market Impacts of a Large-Scale Public Works Program: Evidence from the Indian Employment Guarantee Scheme’, IZA Discussion Paper No. 6858.

| Annex table 1: State-wise Distribution of MGNREGS Households as per Occupation | | Self-employed in agriculture | casual labour in agriculture | casual labour in non- agriculture | Self-employed in non- agriculture | regular wage or salaried earnings | Others | | Andaman | 41 | 2 | 14 | 8 | 33 | 2 | | Andhra Pradesh | 32 | 44 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 2 | | Arunachal Pradesh | 86 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | | Assam | 56 | 9 | 11 | 19 | 3 | 1 | | Bihar | 18 | 51 | 15 | 13 | 1 | 3 | | Chhattisgarh | 49 | 41 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | | D&N Haveli | 23 | 7 | 24 | 0 | 46 | 0 | | Goa | 9 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 75 | 0 | | Gujarat | 47 | 40 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | | Haryana | 11 | 34 | 35 | 6 | 14 | 1 | | Himachal Pradesh | 41 | 1 | 29 | 13 | 13 | 3 | | Jammu Kashmir | 35 | 5 | 35 | 16 | 8 | 2 | | Jharkhand | 50 | 6 | 32 | 9 | 2 | 1 | | Karnataka | 32 | 42 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 2 | | Kerala | 11 | 20 | 39 | 16 | 10 | 5 | | Lashadweep | 8 | 0 | 35 | 2 | 53 | 1 | | Madhya Pradesh | 44 | 25 | 17 | 9 | 4 | 1 | | Maharashtra | 41 | 45 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 0 | | Manipur | 52 | 3 | 3 | 24 | 15 | 2 | | Meghalaya | 52 | 15 | 5 | 19 | 8 | 1 | | Mizoram | 76 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 11 | 1 | | Nagaland | 59 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 20 | 7 | | Orissa | 40 | 21 | 17 | 16 | 3 | 2 | | Pondicherry | 16 | 37 | 31 | 2 | 10 | 4 | | Punjab | 4 | 33 | 33 | 17 | 11 | 1 | | Rajasthan | 44 | 4 | 30 | 12 | 6 | 3 | | sikkim | 79 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 0 | | Tamil Nadu | 16 | 50 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 1 | | Tripura | 26 | 7 | 39 | 18 | 6 | 4 | | Uttar Pradesh | 33 | 22 | 30 | 11 | 2 | 1 | | Uttaranchal | 48 | 6 | 27 | 15 | 3 | 1 | | West Bengal | 19 | 45 | 13 | 18 | 5 | 1 | | All-India | 34 | 31 | 17 | 12 | 5 | 1 | | Source: author's calculation based on NSSO data |

|