| | CONTENTS | | | PART - I | | Sr. No. | Particulars | | | Letter of Transmittal | | 1 | Vision Document for UCBs | | | PART - II | | 1 | Chapter 1 - Introduction | | 2 | Acknowledgements | | 3 | List of Abbreviations | | 4 | Chapter 2 - Executive Summary | | 5 | Chapter 3 - Guiding Principles | | 6 | Chapter 4 - Review of Regulatory Policies and Financial Position of UCBs | | 7 | Chapter 5 – International Experience | | 8 | Chapter 6 – Regulatory Framework for UCBs | | 9 | Chapter 7 – Capital Augmentation Framework for UCBs | | 10 | Chapter 8 – Resolution and Consolidation of UCBs | | Annexes | | | 11 | Annex 1 – Meetings of the Committee | | 12 | Annex 2 - Feedback received from the UCB Sector | | 13 | Annex 3 –List of Federations of UCBs, which Responded to Questionnaire | | 14 | Annex 4 – Stakeholder Interaction | | 15 | Annex 5 – Legal Framework for Regulation of UCBs | | 16 | Annex 6 - Sample Study of Member and Non-Member Deposits | | 17 | Annex 7 - Regulatory Frameworks for UCBs, UNBs, SFBs and RRBs | | 18 | Annex 8 - Board of Management | | 19 | Annex 9 – Letter of Dissent from Shri Jyotindra M Mehta | | Boxes | | | 20 | Box 1 - Structuring capital in UCBs | | 21 | Box 2 - Dual Control of UCBs | | 22 | Box 3 - Proportionate Regulation | | 23 | Box 4 - Umbrella Organization | | 24 | Box 5 - Derived CRAR | | TABLES | | | 25 | Table 1 - Share of UCBs in the Banking Sector | | 26 | Table 2 - Region-wise distribution of UCBs, branches, deposits and advances (As on March 31, 2020) | | 27 | Table 3 - SWOT analysis of UCBs | | 28 | Table 4 - Major regulatory provisions for UCBs, UNBs, SFBs and RRBs | | 29 | Table 5 - Movement in the number of weak UCBs since 2014 | | 30 | Table 6 - Mergers in the UCB Sector since 2005 | | CHARTS | | | 31 | Chart 1 - Growth in the UCB Sector since 1967 | | 32 | Chart 2 - GNPA & NNPA Ratios (As on March 31, 2020) | | 33 | Chart 3 - Earnings Parameters (NIM, RoA, RoE) (As on March 31, 2020) | | 34 | Chart 4 - Interest Income on Loans and Advances (As on March 31, 2020) | | 35 | Chart 5 - State-wise distribution of UCBs | | 36 | Chart 6 - Deposits, Advances, and corresponding growth (2016 to 2020) | | 37 | Chart 7 - GNPA, NNPA and PCR of UCBs (2016 to 2020) | | 38 | Chart 8 - RoA, RoE and NIM of UCBs (2016 to 2020) | | 39 | Chart 9 - Distribution of UCBs with CRAR <9% (2016 to 2020) | | 40 | Chart 10 - Rating-wise distribution of UCBs (2016 to 2020) | | 41 | Chart 11 - Number of UCBs under AID (2016 to 2020) | | 42 | Chart 12 - Group-wise number of UCBs and % share (March 31, 2020) | | 43 | Chart 13 - Share in total Deposits of UCBs Sector (%) (2018 to 2020) | | 44 | Chart 14 - Share in total Loans and Advances of UCB Sector (%) (2018 to 2020) | | 45 | Chart 15 - NIM of UCBs (%) (2018 to 2020) | | 46 | Chart 16 - RoA of UCBs (%) (2018 to 2020) | | 47 | Chart 17 - Cost to Income Ratio of UCBs (%) (2018 to 2020) | | 48 | Chart 18 - GNPA Ratio (%) (2018 to 2020) | | 49 | Chart 19 - NNPA Ratio (%) (2018 to 2020) | | 50 | Chart 20 - UCBs whose licences have been cancelled (2015 to 2020) |

PART - I VISION DOCUMENT FOR URBAN CO-OPERATIVE BANKS The Primary (Urban) Cooperative Banks (UCBs) play an important role in furthering financial inclusion by generally providing traditional, if not the more modern, banking services to persons in the less included segments of the economic strata. World over, financial cooperatives in different forms, as banks and closed loop societies with access to the payment system, have varying market presence. In India, only the financial cooperatives which are licensed to undertake banking business are regulated and supervised by the financial sector regulator, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The banks in the rural cooperative sector are supervised by NABARD, although regulated by the RBI. 2. UCBs have the potential to be the harbinger of economic empowerment of the large number of financially excluded persons in the country. As per information provided to the Committee, the number of borrowers of UCBs is 67 lakh. This is not a small number by itself and there are many cases of transformational changes that UCBs have brought to its customers. However, seen in the context of a very large number of persons yet to have access to formal credit, what has been achieved is not enough either from the standpoint of potential or need. The factors that have resulted in sub-potential performance of the UCB sector are multifarious, some endogenous to the sector and others external. 3. There were two broad sources of constraints because of which the sector has underperformed. The first set of factors are internal to the sector. Many UCBs are small and do not have either the capability - financial or human resources – and/or possibly inclination to provide technology-enabled financial services. These banks continue to leverage on member loyalty to remain in business. This can wane with time, generational changes and, of course, competition. Secondly, because of their small size, a large number of these banks have not had the benefit of professional management and committed governance by people who understand not only the spirit of co-operation but also principles of banking to take a bank to the next level. While one of the arguments for the existence of smaller cooperatives is that they actually reduce intermediation costs, the empirical evidence of the relatively higher Net Interest Margins (NIMs) of the smaller cooperative banks may be pointing to the contrary. These are not translating into sustainable return on assets either. While high cost to income ratio coupled with high NPAs are among the reasons, the unsustainability of the low scale of operations is at the core of the problem. 4. The second set of constraints are external to the banks. These emanate from the rather restrictive regulatory environment under which they have had to operate. This regulatory approach has been driven by several factors. The dual control regime that characterised the regulatory legislation for UCBs meant that many aspects of a bank’s functioning, which impinged on the sustainable operations of the bank, were outside the purview of the RBI. Similarly, the UCBs did not have many avenues to raise capital and the cooperative principle of “one member – one vote” led to the investment horizon of a shareholder being largely borrowing centric, making it even more difficult to raise capital when a bank is unable to lend. 5. In the view of the Committee, there is ample space for financial institutions that operate on the principles of co-operation and the inclusivity that they get. As such, the Vision for the UCB sector should be to emerge as the neighbourhood bank of choice powered by passion for inclusive finance as the core of the business model. This can happen only if their operations are founded on financial strength, strong branding, cutting edge technology driven processes, and skilled human resources coupled with an enabling regulatory environment. These internal drivers can be available to a bank either on a stand-alone basis or acquired through network arrangements. There are now several enabling factors, both for the UCBs themselves and the RBI as the regulator, to actualise this vision. These are - the recent legislative changes on the one hand and the grant of ‘in-principle’ approval for the setting up of an Umbrella Organisation (UO) on the other. The measures necessary to pursue this vision are the following: i) Understand the heterogeneity of the sector and frame regulations to harness the USP of each sub-segment The UCB sector displays extreme heterogeneity. There are a large number of small UCBs which embrace cooperative principles. Their membership has several common factors like community, profession, geographical location, etc. They are, however, stymied due to lack of financial resources, inadequately skilled human resources and unprofessional board governance. These, in turn, are outcomes of low scale of operations and impinge on their ability to provide modern banking services run with support of information technology. The regulatory architecture for this kind of banks should harness the advantages of their being run on cooperative principles while creating an imperative to get networked. In such an environment, these banks may be allowed some operational freedom, but they should not be left to drift away from the inclusive finance model. At the other end of the spectrum are very large UCBs, a few of which are larger than some of the smaller commercial banks permitted to function as universal banks. The legislative changes, which not only provide greater powers to the RBI but also additional capital raising opportunities for UCBs, should be used to allow such banks to grow within the cooperative structure. Depending on the level of capital, the UCBs should be regulated and enabled to function on the lines of a Small Finance Bank or Universal Bank as the case may be. ii) Umbrella Organisation should be expedited and empowered An important recent step has been taken to grant in-principle for the setting up of an Umbrella Organisation. (UO). The thought process on the UO has evolved over a long period of time since it was first mooted in 2006. The UO can and should be seen as a game changer for the sector and as such the National Federation of Urban Co-operative Banks and Credit Societies Ltd (NAFCUB) should expedite the process of setting it up. The UO should be financially strong and be well governed by a professional board and senior management, both of which are fit and proper. As an alternative to mandatory consolidation, the Committee prefers smaller banks acquiring scale through the network of the UO, which is one of the successful models of a strong financial cooperative system globally. The UO should provide cross liquidity and capital support to the UCBs when needed, as also the cloud services for facilitating IT-enabled operations by the member banks. The provision of cloud services has several advantages. It will standardise the IT platform across all the member UCBs and avoid the need for each UCB either to have skills or to hire services for maintaining the IT infrastructure. Further, due to the aggregation being done by the UO, it will provide to all member banks the benefit of innovation on an ongoing basis, including the advantages from emerging advancements on the IT front at lower cost. Since the basic functionalities of the UO have already crystallised, the UO should be adequately empowered to be able to discharge its role as the apex entity of the federating UCBs. The assessment of the eligibility of the UO to get a Certificate of Registration should inter alia look at the control function capabilities of the UO. The UO should be the branding partner for the member UCBs and both because of this and the business model itself, the UO has a significant systemic role. It should therefore be regulated and supervised closely. Recognising the important role of the UO in providing operational and financial strength to the smaller UCBs, the differentiated regulation should have a built-in incentive for the smaller UCBs to join in. A lot of effort has been made by various stakeholders to strengthen the skill sets of personnel working in UCBs and the members of their boards. The UO can emerge as the focal point for identifying training needs of the staff and directors of its member banks. It will need to train the persons working at the front end of the member banks and also on other aspects of their banking business. The UO is envisaged as the arrangement for the smaller entities to acquire scale through network. However, it can also emerge as the brand builder for the cooperative banking sector in its entirety. While there may not be a regulatory imperative for the larger banks to federate with the UO, steps should be taken by the system to encourage the larger UCBs to embrace the UO. The UO’s capital required to get a Certificate of Registration (COR) should be raised by its promoters and others who would support the establishment of the UO. Once the required capital has been raised, COR is issued and permission to commence business has been granted, the RBI could consider providing a one-time grant to the UO for a specific objective tied to the IT support the UO intends to provide to its member banks. This will not be part of the equity capital and hence obviates the typical conflict of interest arising from the regulator being a shareholder in the regulated entity. Since aggregation of IT services will be a financial inclusion enabler and can also contribute to system-stability through standardisation of the IT interface, there is justification for RBI’s financial support to the UO. iii) Enable the larger UCBs to raise capital The legislative changes have provided new instruments for raising capital. They also enable raising share capital at a premium. In the absence of listing facility, the securities issued by the UCBs do not have a secondary market through an exchange. However, a mechanism for issue of shares at a premium and facilitating bilateral transfer of shares through the concerned bank needs to be put in place. Adequate disclosure requirements, guidance for determining the intrinsic value of shares should be provided. Since, the cooperatives work on the principle of open membership, which implies primary issuance of shares on tap, it must be stipulated that such issues cannot be priced at below the book value of shares. Further, to facilitate investor interest in subscribing to issuances of non-voting securities like Perpetual Non-Cumulative Preference Shares, allowing limited lending to such investors should be explored. iv) Strengthen Governance, particularly in the Larger UCBs One of the major concerns with UCBs has been their poor governance. Prior to the recent legislative changes, the RBI did not have any powers with respect to board composition and executive appointments. Now that there is parity in this regard with commercial banks, the compliance with fit and proper requirements should be sine qua non for any regulatory authorisation, particularly for the large banks. Concurrently steps should be taken to enhance the skill sets of the Board Members through specially curated training programmes. v) Make Regulatory Authorisations Automatic The legislative framework has provided adequate headroom to the RBI to allow UCBs to grow organically. For the commercial banks, the permission to open branches is automatic and it is withdrawn in specific cases as a regulatory response to deal with entity specific concerns. The approach with regard to UCBs has been the contrary. To enable the UCBs to grow and harness their potential, similar approach as with commercial banks may be adopted with suitable modifications having regard to the differential regulation for different tiers of banks. Similar policy-based approach may be applied with regard to scheduling, authorised dealer licensing etc. vi) Maintain Regulatory Neutrality towards Voluntary Mergers in the normal course but encourage them as an alternative to mandatory amalgamations; Strengthen Supervisory Action Framework In the past, mandatory merger was not possible. As such wherever consolidation was seen as a possible alternative to avoid a weak bank slipping into insolvency, in the absence of voluntary proposals, RBI could not force any mergers. In the wake of legislative changes, there is a school of thought that the smaller UCBs should be consolidated. The question of an economically viable size of a bank was debated in the Committee. Having regard to the idea of creating scale through network under the UO, a minimum net worth of ₹2 crore for unit banks and ₹5 crore for single district banks on top of the prescribed CRAR was agreed upon. This provides an embedded size requirement for UCBs on a stand-alone basis. The Committee, therefore, believes that while regulatory neutrality towards voluntary mergers should be the default approach, the powers to order compulsory amalgamation should be used as the backstop to encourage voluntary mergers of banks that are not complying with the regulatory capital requirements but are still solvent. This will also require that supervisory interventions are more timely and decisive. The RBI should develop a playbook of alternative options linked to size and complexity of a weak bank to enable the choice of a particular resolution tool. vii) Empower TAFCUB The Task Force on Urban Co-operative Banks (TAFCUB) was invented as a non-legislative alternative to deal with the problem of dual control. Its success largely hinged on constructive voluntarism and cooperation. As with any such arrangements, over time, the TAFCUB’s role and influence in dealing with weak banks waned, to an extent accentuated by the mandatory nature of responses under the Supervisory Action Framework which left TAFCUB bereft of any leeway to find alternatives to deal with weak banks. One could argue that with the legislative changes TAFCUB may not be necessary at all. The Committee feels otherwise. The TAFCUB should be involved at the incipient stages where signs of stress are seen while the bank has still not hit the SAF triggers. The TAFCUB can also suggest measures beyond, rather than in place of, mandatory actions as per the SAF and could help identify suitors for voluntary mergers. The legislative framework still requires coordination with the RCS of a state or the Central Registrar. TAFCUB can continue to be the forum for such coordination. Once the UO is in place, the functionaries of the UO should be invited to the TAFCUB for dealing with UO-related or member bank-related issues. viii) Don’t target a market share for the UCBs It is normally a practice to target a market share, or even a specific rate of growth, as part of the vision. Some of the feedback received by the Committee suggested such an approach. The Committee did not consider this feasible for many reasons. The Committee realises that the market share of UCBs will be influenced by several factors exogenous to the sector, particularly how the competition performs, customer choices and the general economic situation. Whether it is the pursuit of market share or a rate of growth, it could lead to rush for balance sheet growth entailing the risk of adverse selection, thereby sowing seeds of systemic or idiosyncratic instability and proving detrimental to the larger interest of the sector itself. Instead, the Committee is of the opinion that the regulatory policy should be more enabling and the UCBs themselves should act responsibly to achieve sustainable growth. ix) Licensing of New UCBs may commence after the UO has stabilised There were suggestions that licensing of new UCBs should be immediately opened up. There are over 1500 UCBs already. The Committee has suggested that the existing UCBs may be allowed to expand their footprint. Proliferation of the number of UCBs is not by itself an instrumentality of strengthening the sector. Globally too, the trend has been for the number of financial cooperatives to come down. The effort of the Sector and RBI should be to instil and deepen public confidence in UCBs as efficient and dependable financial intermediaries by ensuring that the existing entities are working on a sound footing and the weak ones among them are either quickly nursed back to health or resolved in as non-disruptive manner as possible without further loss of time. At the same time, the small UCBs with the support of the UO can emerge as the neighbourhood bank of choice. Therefore, the Committee suggests that the grant of new licences for setting up UCBs could be considered after the UO satisfactorily emerges as a stabilising arrangement. x) Conclusion In sum, the vision of the Committee has been to make space for more and more operational and strategic autonomy of co-operative institutions and introducing larger regulatory requirements that provide system stability. This, the Committee hopes, will foster a healthy co-operative as well as a stable banking sector. The specific recommendations contained in Part II are largely driven by this vision.

PART - II REPORT OF THE EXPERT COMMITTEE ON URBAN CO-OPERATIVE BANKS Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION 1.1 Co-operatives are people-centred enterprises owned, controlled, and run by and for their members to realise their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations. Historically, co-operatives emerged by challenging the primacy of capital. While all the services rendered by a firm were pre-negotiated, capital was compensated with the residuals. The objective of a capital-centric corporation was completely predicated on maximizing these residuals. The other systems that evolved around this objective were also oriented towards the primacy of and reward for capital1. Whether it pertained to control, rewards or performance evaluation, they were broadly focussed on how a firm was delivering returns to the investors of risk capital. In this sense, the co-operatives were a different form of organisation. 1.2 Co-operatives, while acknowledging the importance of capital, started with questioning the primacy of capital and suggested that the usage or patronage could be an alternative basis to determine the primacy, with capital being rewarded on the basis of a pre-negotiated compensation. This was enshrined in the older principle of “limited interest on capital”, though the current principles have used the phraseology that represents more complicated financial arrangements that the members might have with the co-operative. It is now termed as ‘member economic participation’. 1.3 The primacy of patronage shifted the focus from capital to a particular service, drawing from the strength of aggregation of common interests of people. This poses a peculiar problem in case of financial services which are three-fold: -

Financial co-operatives have, at the core, the very aspect that the co-operatives aim to reject: that of capital; -

The financial co-operatives, on the one hand, serve the interests of the savers (thrift) who could be seen as suppliers of capital to the world at large, and on the other hand, serve the interests of the borrowers (credit) who are consumers of capital. These are competing needs; but financial co-operatives have structured them as a unique institutional arrangement on the principle of mutuality where the platform seeks to become an exchange to settle the competing needs within the community without external institutional intermediation leaving the co-operative to go to the outside world only when there is still a residual need, beyond what is cleared by the principle of mutuality. - The members are also not uniquely net borrowers or net savers. Their role could change from time to time.

1.4 In the case of financial co-operatives, the unique features of a co-operative entity, viz. being member-owned, member-driven and member-controlled businesses, would translate to increasing the return on savings and reducing the interest on loans to members while ensuring adequate margins and surpluses for ploughing back for sustainability and growth. Ideally, a co-operative should do its core business only with its members and not with the public at large. On the other hand, a bank, by definition, is expected to deal with the public at large. By virtue of being a bank, there is a heightened sense of safety because banking institutions are not only licenced after due diligence but are also highly regulated compared to other entities in the financial sector. A financial co-operative becomes a bank when it is licenced to receive deposits, which are withdrawable on demand, from non-members as well. It also becomes eligible to be a part of the payment system. Once an institution is a bank, it can also offer complex products beyond plain vanilla savings and credit facilities. Some of these products could be provided only if the institution is large and a part of the interconnected world – whether it is for remittances through the payment system or offering a credit card facility or facilitating transactions on other instruments such as mutual funds, derivatives, and the like. Since banks are in the business of leverage, the question of capital becomes very important for the stability of the organisation. Herein lies the paradox: an organisation designed to meet the requirements of its members on the principle of mutuality, by becoming a bank, morphs into an organisation where capital is central to its operations. 1.5 Financial co-operatives the world over play a very important role of financial intermediation, particularly for the people who are not readily catered to by the mainstream banks. In India also, financial co-operatives are in existence for more than 100 years. While the financial co-operatives had been working as banks earlier too, they were brought under the purview of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 (BR Act), and thereby under the regulatory domain of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), in the year 1966. Primary (Urban) Co-operative Banks in India 1.6 As stated above, co-operative banks, including Primary Co-operative Banks (popularly known as Urban Co-operative Banks or UCBs), are co-operative societies that transact the business of banking2. While co-operative credit societies provide financial accommodation to its members by accepting deposits from its members and lending to them, co-operative banks provide financial accommodation by accepting deposits from the public and lending to its members. For a co-operative bank, the distinction between the deposit of a member and non-member ceases and in view of the normal regulatory capital requirements applied to them, they are able to work with a high leverage. As such, co-operative banks are exceptions in the co-operative sector, wherein the resources used for lending and investment come from the public rather than just their members. 1.7 The legal status of co-operative banks is akin to banking companies in many ways. Both are body corporates by the name in which they are registered, with limited liabilities, which can sue and be sued in their own name, with independent legal personalities distinct from their shareholders/members, with power to acquire, hold and dispose of property and enter into contract. However, there are certain vital distinctions between the two types of banks, primarily arising out of their structure, which need to be considered while formulating a regulatory regime for UCBs. The most fundamental difference between the banking companies and co-operative banks is in the rights of the shareholders to vote in resolutions. While in the case of a banking company, each share has a vote (subject to the limitations imposed by Section 12 of the BR Act), in the case of a co-operative bank, each shareholder has only one vote irrespective of the number of shares held. 1.8 The first watershed moment in the evolution of regulatory framework for co-operative banks in India came when they were brought under the purview of the BR Act in the year 1966. Owing to certain characteristics of the co-operative banks, distinct from the banking companies, a separate chapter was added in the Act. However, some of the important provisions, mainly related to governance, capital, audit and resolution including winding up were not applied on the co-operative banks. 1.9 The regulation of co-operative banks by the RBI so far has largely been restricted to certain aspects of their functions, mainly those directly related to ‘banking’, giving rise to the dual regulation, with governance, audit and winding-up related functions largely being in the domain of the State Governments in case of ‘single-state’ banks (i.e. banks whose area of operation is confined to a single state) and the Central Government in case of multi-state banks. Governance functions have rather been loosely regulated even by the Governments because of the perception of them being democratic institutions. The problem has been highlighted in the reports of many of the committees set up by the RBI in the past, more notably by the High-Power Committee on Urban Co-operative Banks (Chair: Shri K. Madhava Rao, 1999), the Expert Committee on Licensing of New Urban Co-operative Banks (Chair: Shri Y. H. Malegam, 2011) and the High-Powered Committee on Urban Co-operative Banks (Chair: Shri R. Gandhi, 2015). 1.10 Owing to lack of the desired level of regulatory comfort on account of the structural issues related to capital and the gaps in the statutory framework, the regulatory policies for co-operative banks have been restrictive with regard to their business operations, which, to some extent, have been one of the reasons affecting their growth. With the enactment of the Banking Regulation (Amendment) Act, 2020, the statutory gaps have been addressed to a very large extent. Constitution of the Expert Committee 1.11 It is in this context that the RBI, as part of the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies released along with the Monetary Policy Statement on February 05, 2021, announced setting up of an Expert Committee for UCB sector (‘the Committee’) involving all stakeholders in order to provide a medium-term road map to strengthen the sector, enable faster rehabilitation/resolution of UCBs, as well as to examine other critical aspects relating to these entities. The Committee was constituted vide Press Release dated February 15, 2021 with the following terms of reference and composition. Terms of Reference (TOR) -

Take stock of the regulatory measures taken by the RBI and other authorities in respect of UCBs and assess their impact over last five years to identify key constraints and enablers, if any, in fulfilment of their socio-economic objective. -

Review the current Regulatory/Supervisory approach and recommend suitable measures/changes to strengthen the sector, taking into account recent amendments to the BR Act. -

Suggest effective measures for faster rehabilitation / resolution of UCBs and assess potential for consolidation in the sector. -

Consider the need for differential regulations and examine prospects to allow more leeway in permissible activities for UCBs with a view to enhance their resilience. -

Draw up a vision document for a vibrant and resilient urban co-operative banking sector having regards to the Principles of Cooperation as well as depositors’ interest and systemic issues. Composition of the Committee Shri N. S. Vishwanathan

Former Deputy Governor, RBI | Chairman | Shri Harsh Kumar Bhanwala

Former Chairman, NABARD | Member | Shri Mukund M Chitale

Chartered Accountant | Member | Shri N. C. Muniyappa

IAS (Retired) | Member | Shri R. N. Joshi

IAS (Retired) | Member | Prof M. S. Sriram

IIM Bangalore | Member | Shri Jyotindra M. Mehta

President, NAFCUB | Member | Shri Neeraj Nigam,

Chief General Manager-In-Charge Department of Regulation, RBI | Convenor | Approach / Methodology 1.12 The Committee held 14 meetings through video conferencing between (and including) March 8, 2021 and July 28, 2021 as detailed in Annex 1. It also held discussions with various stakeholders and experts and sought feedback from the UCB sector with the help of a questionnaire to elicit their responses on some of the issues drawn from the ToR (Annex 2). The questionnaire was emailed to all the UCBs and their Federations to seek their responses. Responses were received from 654 UCBs and 9 Federations (Annex 3). 1.13 The Committee formed sub-groups for interacting with select stakeholders such as Federations of UCBs, UCBs, Registrars of Co-operative Societies, auditors, technology providers and experts. The list of stakeholders who interacted with the Committee along with the dates of the interactions are given in Annex 4. All these interactions were conducted through video conference. The Committee also received feedback submitted to it suo motu by certain persons / organizations. The Committee also looked at the data and analyses related to various financial parameters of UCBs presented before it by the secretariat, to be able to formulate its opinion on the relevant areas. 1.14 The Committee has given its report based largely on the unanimous views of the members on the areas covered under the TOR. Differing views in certain areas given by Shri Jyotindra M Mehta, President, NAFCUB are enclosed as Annex 9. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Committee gratefully acknowledges the support provided by the secretariat headed by Shri Neeraj Nigam, Chief General Manager-In-Charge, Department of Regulations (DoR), RBI and comprising Shri T V Rao, General Manager, Shri Prabhat Ranjan, Deputy General Manager, Shri Praveen Kumar Yadav, Assistant General Manager, Shri Dinesh Kumar, Manager, Shri Manish Manhar, Manager and Shri Ashish Kumar Meena, Manager from DoR, RBI. The Committee also places on record its appreciation for the assistance rendered by Shri Abhilash Ankathil, Deputy Legal Advisor, RBI and a special invitee to the Committee meetings, in understanding the implications of various legal issues in general and those arising from the recent amendments to the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 in particular. The Committee would like to thank the stakeholders including the UCBs and their national and state level Federations who interacted with the Committee and/or responded to the questionnaire. The Committee also benefited from its interactions with Registrars of Co-operative Societies of select states and the Central Registrar of Co-operative Societies, experts in the field of co-operative banking, group of Chartered Accountants (CA-COB) and select IT service providers. The presentation made before the Committee on the Umbrella Organisation (UO) by the NAFCUB’s consultants was useful in understanding the shape the UO is expected to take and its business model. Finally, the Committee would like to thank the Deputy Governor (Shri M Rajeshwar Rao) and his team for agreeing to brief the Committee on the basic issues that the RBI would like the Committee to examine. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS | AACS | As Applicable to Co-operative Societies | | ACB | Audit Committee of the Board | | AD | Authorized Dealer | | AFS | Available for Sale | | AID | All-inclusive Directions | | AIFI | All Indian Financial Institution | | ALM | Asset-Liability Management | | ANBC | Adjusted Net Bank Credit | | ATM | Automated Teller Machine | | BC | Business Correspondent | | BF | Business Facilitator | | BoD | Board of Directors | | BoM | Board of Management | | BPCE | Banques Populaires-Caisses d’Epargne | | BR Act | Banking Regulation Act, 1949 | | CAMELS | Capital Adequacy, Asset Quality, Management, Earning, Liquidity, and System and Controls | | CAPEX | Capital expenditure | | CBS | Core Banking Solutions | | CD | Credit-Deposit / Certificate of Deposit | | CDA | Central Delegate Assembly | | CEO | Chief Executive Officer | | CEOBSE | Credit Equivalent Amount of Off-balance Sheet Exposure | | CET1 | Common Equity Tier 1 | | CGTMSE | Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises | | CIC | Credit Information Company | | CISBI | Central Information System for Banking Infrastructure | | COVID | Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) | | CRAR | Capital to Risk-Weighted Assets Ratio | | CRCS | Central Registrar of Co-operative Societies | | CRE | Commercial Real Estate | | CRE-RH | Commercial Real Estate - Residential Housing | | CRILC | Central Repository of Information on Large Credits | | CRR | Cash Reserve Ratio | | CTS | Cheque Truncation System | | CU | Credit Union | | DCC | District Consultative Committee | | DCCB | District Central Co-operative Bank | | DFS | Department of Financial Services | | DICGC | Deposit Insurance & Credit Guarantee Corporation | | DLRC | District Level Review Committee | | DOR | Department of Regulation | | DoS | Department of Supervision | | D-SIB | Domestically Systemically Important Bank | | ECB | European Central Bank | | EPN | Entry Point Norm | | ESOP | Employee Stock Ownership Plan | | FALLCR | Facility to Avail Liquidity for Liquidity Coverage Ratio | | FC | Financial Co-operative | | FSWM | Financially Sound and Well-Managed | | GFC | Global Financial Crisis | | GNPA | Gross Non-Performing Assets | | GoI | Government of India | | GSA | Graded Supervisory Action | | G-SIB | Globally Systemically Important Bank | | HPC | High Powered Committee | | HR | Human Resources | | HTM | Held to Maturity | | IAS | Indian Administrative Service | | IBPS | Institute of Banking Personnel Selection | | IDRBT | Institute for Development & Research in Banking Technology | | IIM | Indian Institute of Management | | IPDI | Innovative Perpetual Debt Instruments | | IRAC | Income Recognition and Asset Classification | | IT | Information Technology | | JPC | Joint Parliamentary Committee | | KYC | Know Your Customer | | LAB | Local Area Bank | | LAF | Liquidity Adjustment Facility | | LCR | Liquidity Coverage Ratio | | LFAR | Long Form Audit Report | | LTD | Long Term (Subordinated) Deposits | | LTV | Loan-to-Value | | MC | Master Circular | | MD | Managing Director | | MIS | Management Information System | | MLI | Member Lending Institution | | MMCB | Madhavpura Mercantile Co-operative Bank | | MoU | Memorandum of Understanding | | MSF | Marginal Standing Facility | | MSME | Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise | | MUDRA | Micro Units Development & Refinance Agency Ltd | | NABARD | National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development | | NAFCUB | National Federation of Urban Co-operative Banks and Credit Societies Ltd. | | NBFC | Non-Banking Finance Companies | | NDS-OM | Negotiated Dealing System - Order Matching | | NDTL | Net Demand and Time Liabilities | | NEFT | National Electronic Funds Transfer | | NGO | Non-Government Organization | | NHB | National Housing Bank | | NIM | Net Interest Margin | | NNPA | Net Non-Performing Assets | | NOC | No-Objection Certificate | | NPA | Non-Performing Assets | | NPCI | National Payments Corporation of India | | NRE | Non-Resident External | | NRO | Non-Resident Ordinary | | NSFR | Net Stable Funding Ratio | | OPEX | Operating Expenses | | OSS | Offsite Surveillance System | | PACS | Primary Agricultural Credit Society | | PAN | Permanent Account Number | | PCA | Prompt Corrective Action | | PCPS | Perpetual Cumulative Preference Shares | | PCR | Provision Coverage Ratio | | PFRDA | Provident Fund Regulatory & Development Authority | | PNCPS | Perpetual Non-Cumulative Preference Shares | | POS | Point of Sale | | PPI | Prepaid Payment Instrument | | PSL | Priority Sector Lending | | RBI | Reserve Bank of India | | RBIA | Risk Based Internal Audit | | RCPS | Redeemable Cumulative Preference Shares | | RCS | Registrar of Co-operative Societies | | RDA | Regional Delegate Assembly | | RDB | Recovery of Debt Due to Banks & Financials Institutions and Bankruptcy Act, 1993 | | RIDF | Rural Infrastructure Development Fund | | RNCPS | Redeemable Non-Cumulative Preference Shares | | RoA | Return on Assets | | RoE | Return on Equity | | RRB | Regional Rural Bank | | RTGS | Real-Time Gross Settlement System | | SAF | Supervisory Action Framework | | SARFAESI | Securitization and Reconstruction of Finance Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest | | SC/ST | Scheduled Caste / Scheduled Tribe | | SCB | Scheduled Commercial Bank | | SCRA | Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act, 1956 | | SEBI | Securities and Exchange Board of India | | SEZ | Special Economic Zone | | SFB | Small Finance Bank | | SGL | Subsidiary General Ledger | | SIDBI | Small Industries development Bank of India | | SLBC | State-Level Bankers Committee | | SLR | Statutory Liquidity Ratio | | SME | Small and Medium Enterprise | | SRO | Self-Regulatory Organization | | StCB | State Co-operative Bank | | SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats | | TAFCUB | Task Force on Urban Co-operative Banks | | TDS | Tax Deduction at Source | | TOR | Terms of Reference | | UNB | Universal Bank | | UCB | Primary (Urban) Co-operative Bank | | UK | United Kingdom | | UO | Umbrella Organization | | USA | United States of America | | USD | United States Dollar | | WTC | Whole-Time Chairman | | WTD | Whole-Time Director | Chapter 2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Overview 2.1 The regulation of co-operative banks by the RBI so far has largely been restricted to their ‘banking’ business, with governance, audit, reconstruction/amalgamation and winding-up related functions being in the domain of the state governments (in case of single-state banks, i.e., banks whose area of operation is confined to a single state) and the Central Government (in case of multi-state banks, i.e., banks whose area of operation extends to more than one state). Governance functions have rather been loosely regulated even by the Governments because of the perception of the UCBs being democratic institutions. (Para 1.9) 2.2 Owing to lack of the desired level of regulatory comfort on account of the structural issues including ‘capital’ and the gaps in the statutory framework, the regulatory policies for co-operative banks have been restrictive with regard to their business operations, which, to some extent, has been one of the reasons affecting their growth. With the enactment of the Banking Regulation (Amendment) Act, 2020, the statutory gaps have been addressed to a very large extent. (Para 1.10) 2.3 The Committee considered it appropriate to articulate the guiding principles which would inform its approach to the issues covered by the Terms of Reference, in assimilating the feedback received during stakeholder consultations, directing the deliberations within the Committee, and for identifying most of the recommendations. The Committee notes that having regard to the heterogeneity of the sector, the smaller banks, which are more rooted in co-operative principles, should be allowed to acquire scale through the network of the Umbrella Organisation, while the larger ones should have scale on a stand-alone basis. (Para 3.1 and 3.2). 2.4 The Committee observed that focus of the regulatory policies during the last five years has been to mitigate the risks in the banking business of UCBs, keeping in view the various constraints such as heterogeneity of the sector, limitations in the form of constraints in raising capital and non-availability of resolution tools under the provisions of the BR Act and, in general, lack of adequate regulatory control of the RBI. The Committee, however, did not find any regulatory changes brought about in the last five years to be largely limiting the growth of the UCBs. Nevertheless, it noted that the restrictive approach of the earlier years towards branch expansion, scheduling, which continued to be pursued on top of a more enabling regulatory approach towards business operations of the other banking and non-banking entities did hamstring the ability of the UCBs to grow. The Committee also noted that this approach was rooted in the inadequacy of regulatory powers with the RBI under the then existing legislative framework. (Para 4.4) 2.5 The Committee noted that the UCB sector has been under stress for quite some time. It felt that given the importance of the sector in furthering financial inclusion and considering the large number of its customer base, it is imperative that the strategies adopted for the regulation of the sector are comprehensively reviewed so as to enhance its resilience and provide an enabling environment for its sustainable and stable growth in the medium term. (Para 4.5.8) 2.6 The Committee carried out a SWOT analysis of the UCB sector and identified factors contributing to their strength and weakness as also the opportunities and threats they are likely to encounter. (Table 3) 2.7 In the Committee’s view, while it was possible that the structural factors arising from the co-operative character underlying the UCBs could still pose some challenges, the amendments to the BR Act address to a large extent the gaps in the legislative framework, which informed the extant approach of the RBI towards regulation and supervision of UCBs. Consequently, since the UCBs have the potential of driving financial inclusion and credit delivery to those with limited means, the regulatory policies can now be more enabling. (Para 6.2.2) 2.8 The Committee also discussed the issue of parallel statutory provisions in the BR Act and the co-operative societies’ laws, which was raised by UCBs and their federations during their interaction with the Committee. These are considered more to be administrative challenges rather than legislative conflicts. (Para 6.2.3) 2.9 The Committee observed that given the heterogeneity in the sector, a tiered regulatory framework with more than two tiers is required to balance the spirit of mutuality and co-operation more prevalent in banks of smaller sizes and those with limited area of operation vis-à-vis the growth ambitions of the large-sized UCBs to spread their area of operation and undertake more complex business activities on par with commercial banks. The Committee agreed that the deposit size can continue to be the basis for categorising banks into regulatory tiers, as for a normally functioning bank, deposit size can broadly serve as proxy for capital size and net worth. Further, additional tiers could be created to cater to the aspirations of the larger UCBs to undertake business akin to that of SFBs and UNBs. (Para 6.4.3) 2.10 With regard to the minimum capital and reserve (net worth) requirement for UCBs, irrespective of CRAR, one view favoured the status quo, arguing that the smaller UCBs have a long history of surviving and serving their customers, despite their small size. (Para 6.5.1.4) 2.11 The Committee felt that a liberal regulatory approach may be adopted for UCBs that meet a certain minimum level of capital and reserves (net worth) and CRAR requirements. Further, membership of the UO might also provide an extra comfort to the regulator as the smaller UCBs would benefit from the products and services provided by the UO. It was felt that UCBs meeting the criteria specified for UNBs or SFBs and having comparable risk management abilities may be regulated on the lines of UNBs or SFBs, as the case may be. (Para 6.6.2) 2.12 With regard to the existing regulatory approach of prescribing sectoral limits for UCBs, the Committee believed that given the heterogeneity in the sector, the monetary ceilings on different categories of loans may be dispensed with, particularly for larger UCBs. Instead, the Committee felt, the regulatory ceilings may be defined as a percentage of Tier I capital of the bank with appropriate monetary ceilings for smaller UCBs having inadequate risk management and risk bearing capacity. For larger UCBs, the monetary ceilings may be decided by their Boards, within the prescribed general exposure limits (for single/group borrowers). (Para 6.6.3) 2.13 At the same time, the Committee recognized the need for UCBs to be well capitalized in proportion to their risk weighted assets. The Committee felt that in line with the principles of proportionate regulation, it may not be desirable to expect smaller UCBs to switch over to Basel III which is complicated and require higher technical competence and skills. However, a higher level of CRAR needs to be prescribed to take care of the market and operational risks, particularly if operational freedom has to be enhanced. While doing so, the Committee also considered that membership of UO, once it becomes operational, would mitigate these risks for UCBs in lower tiers to a certain extent and, therefore, the CRAR requirement can be brought down. However, a glide path should be provided to UCBs to achieve the higher CRAR. (Para 6.6.4) 2.14 The Committee is of the view that the recent amendments to the BR Act need to be supplemented by legislative enablement for listing of certain securities issued by the UCBs. As there is no corresponding law in the co-operative realm, it is difficult to categorise the issuance of securities made by co-operative banks into ‘public offers’ and ‘private placements’ in the manner these are known in case of companies. (Para 7.9.2) 2.15 The Committee noted that even though the present SAF aims to start the resolution process early, close to one third of all UCBs consistently remain under the SAF over the years. This raises concerns about their functioning as also the efficacy of the resolution process. (Para 8.5.2) 2.16 The Committee feels that the ‘multiple indicators - multiple stages’ approach of the existing SAF mechanism needs a relook. If a UCB remains under more stringent stages of SAF for a prolonged period, it may have an adverse effect on its operations and may further erode its financial position. Delay in initiating the resolution process causes inconvenience to the depositors/customers and further leads to erosion in the enterprise value including deposits. Therefore, the Committee, after an extensive deliberation, recommends that the framework may contain a twin indicator only, viz. CRAR and Net NPA, with an emphasis on reducing the time spent by a UCB under SAF. (Para 8.6.1) 2.17 The Committee also finds it appropriate that the additional provisioning suggested by the Inspecting Officers (IOs) should be adjusted from GNPA to arrive at assessed NNPA similar to the adjustments in Tier I capital done to arrive at assessed CRAR. TAFCUB intervention may also be envisaged if the divergence is large, leading to significant increase in NNPA and reduction in CRAR. Such banks may be flagged for discussions in TAFCUB and early intervention. (Para 8.6.2) 2.18 During the process of stakeholder consultation, some UCBs suggested that TAFCUB should have a forum to study early warning signals of UCBs heading towards imposition of SAF. Concerns were expressed over the limited role of TAFCUB after introduction of SAF by the RBI, while some banks also mentioned that the regulatory action taken by the RBI should be in consonance with the decision of the TAFCUB. (Para 8.8.2) Recommendations 2.19 Regulatory Framework A. Categories of UCBs Based on the cooperativeness’ of the banks, availability of capital and other factors, UCBs may be categorised into following four tiers for regulatory purposes: -

Tier 1 - All unit UCBs and salary earner’s UCBs (irrespective of deposit size), and all other UCBs having deposits up to ₹100 crore -

Tier 2 - UCBs with deposits more than ₹100 crore and up to ₹1000 crore -

Tier 3 - UCBs with deposits more than ₹1000 crore and up to ₹10,000 crore -

Tier 4 - UCBs with deposits more than ₹10,000 crore (Para 6.7.1.1) B. Prescriptions for Tier 1 UCBs i) Tier 1 banks having area of operation within a district should have a minimum capital and reserves (net worth) of ₹2 crore and other Tier 1 banks should have a minimum capital and reserves (net worth) of ₹5 crore. ii) A suitable glide path may be provided for achieving the target minimum net worth, provided the banks meet the CRAR requirement. iii) The minimum CRAR stipulation for Tier 1 banks may be as under: | Sr. No. | Condition | Minimum required CRAR

(%) | | 1. | Meets the minimum net worth criteria of ₹2 crore / ₹5 crore and is a member of UO | 9.0 | | 2. | Meets the minimum net worth criteria of ₹2 crore / ₹5 crore but is not a member of UO | 11.5 | | 3. | Does not meet the minimum net worth criteria of ₹2 crore / ₹5 crore but is a member of UO | 11.5 | | 4. | Does not meet the minimum net worth criteria of ₹2 crore / ₹5 crore and is also not a member of UO | 14.0 | iv) There may be no differentiated risk weights. v) Banks meeting the minimum net worth and CRAR criteria may be given general permission to open, during a financial year, branches up to 10 per cent of the number of branches at the end of the previous financial year, subject to a minimum of one branch. The new branch(es) should be opened in an unbanked area within the district of operation of the banks requiring a minimum capital of ₹2 crore, and in current districts of operation or adjoining districts in case of banks requiring a minimum capital of ₹5 crore. The branch in the unbanked area should be front loaded wherever the number of branches to be opened by the bank is less than four. The extant regulations with regard to capital headroom should continue. vi) All other regulatory prescriptions may be in line with the present regulatory guidelines for UCBs, as amended from time to time and subject to the other recommendations of this Committee. vii) As already prescribed for all UCBs by the RBI, 75 per cent of the ANBC/CEOBSE of banks in this tier shall meet PSL criteria and 50 per cent of their credit portfolio should consist of loans of ticket size up to ₹25 lakh. The time given to these banks till March 31, 2024 to get their loan book in conformity with these stipulations is reasonable. (Para 6.7.1.2) C. Prescriptions for Tier 2 UCBs -

Minimum CRAR of 15 per cent3 on credit risk. The minimum CRAR requirement may be reduced by one per cent point upon the bank becoming a member of the UO. -

Additional timeframe (say two years) and glide path may be provided in case a UCB has to achieve the required minimum CRAR for Tier 2 category, on transitioning from Tier 1 to Tier 2 category on account of size of deposits. -

Banks meeting the CRAR requirements may be allowed to open branches in existing districts or contiguous districts (in the state where the bank has its head office) up to 10 per cent of the existing number of branches (subject to minimum one and maximum five) every year under automatic route with a prescription of opening at least 25 per cent of the branches in unbanked areas, subject to headroom capital availability and reporting to RBI. The branch(es) in the unbanked area should be front loaded wherever the number of branches to be opened by the bank in a year is less than four. -

All other regulatory prescriptions may be in line with the present regulatory guidelines for UCBs, as amended from time to time, and subject to the other recommendations of this Committee. -

As already prescribed by RBI for all UCBs, at least 75 per cent of the ANBC/CEOBSE of the UCBs in this tier shall meet the PSL criteria and 50 per cent of their credit portfolio should consist of loans of ticket size up to ₹25 lakh. The Committee also recommends that the hard timeline for achieving the PSL target be replaced with a stipulation that 95 per cent of the incremental portfolio of these banks should be corresponding to the aforesaid prescriptions till the overall loan book conforms to the stipulated composition. (Para 6.7.1.3) D. Prescriptions for Tier 3 UCBs i) Minimum CRAR of 15 per cent as applicable to SFBs ii) A Tier 3 UCB which meets both the entry point capital and the CRAR4 requirements applicable to SFBs may, on the RBI being satisfied that it meets the financial requirements and has a fit and proper Board and CEO, be allowed to function on the lines of an SFB. Such UCBs may be eligible for the following: -

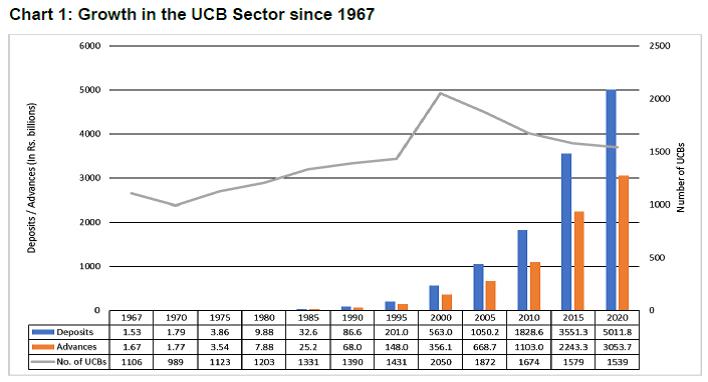

Deemed area of operation across the country and, consequently, deemed permission / NOC from RBI to become a multi-state bank, if it is not already one. -

Branch expansion throughout the country through automatic route, subject to a prescription of opening at least 25 per cent of the branches in unbanked areas and reporting to the RBI. The branch(es) in the unbanked area should be front loaded wherever the number of branches to be opened by the bank is less than four. -

Automatic inclusion in second Schedule to the RBI Act -

AD licensing regime on par with SFBs -

Any other regulatory permissions normally granted to SFBs iii) Tier 3 UCBs not fulfilling the conditions as at (ii) above may have operational freedom on par with Tier 2 UCBs. iv) The loan portfolio of all UCBs in Tier 3 shall conform to the stipulations made for SFBs as per instructions already in place. As in case of banks in Tier 2, the Committee recommends that the hard timeline be replaced with a stipulation that 95 per cent of the incremental portfolio of these banks should be corresponding to the aforesaid prescriptions till the overall loan book conforms to the stipulated composition. v) There may, however, be no sub-target for agriculture under PSL. vi) These banks may voluntarily become members of the UO. (Para 6.7.1.4) E. Prescriptions for Tier 4 UCBs -

Minimum CRAR as per Basel III prescriptions as applicable to UNBs. -

A Tier 4 UCB which meets both the entry point capital5 and CRAR requirements applicable to UNBs as also the leverage ratio may, on RBI being satisfied that it meets the financial requirements and has a fit and proper Board and CEO, be allowed to function on the lines of a universal bank. -

Tier 4 UCBs fulfilling the conditions at (ii) above may have all the operational freedom, including for branch expansion (including the obligation to open 25 per cent of the branches in unbanked areas subject to reporting), scheduling, AD license, etc. on par with UNBs. -

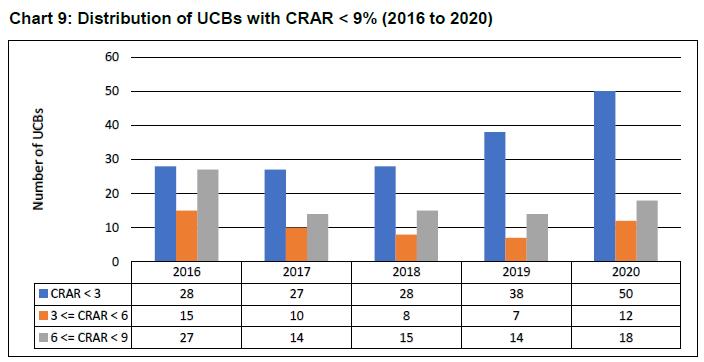

Any bank which is in Tier 4 by virtue of its deposit size but found ineligible to be authorised to function as a universal bank may be provided operational freedom as applicable to Tier 2 UCBs while their regulatory requirements will continue to be as applicable to banks in Tier 4. The loan portfolio of such UCBs shall conform to the stipulations made for SFBs as per instructions already in place. For the reasons outlined in case of Tier 2 banks above, the Committee recommends that the hard timeline be replaced with a stipulation that 95 per cent of the incremental portfolio of these banks should be corresponding to the aforesaid prescriptions till the overall loan book conforms to the stipulated composition. -

These banks may voluntarily become members of the UO. (Para 6.7.1.5) F. Recommendations on Sectoral Exposure Ceilings Regulation of UCBs in Tier 3 and Tier 4 will be largely on par with SFBs and UNBs, respectively. For Tier 1 and Tier 2 banks, including the banks in Tier 3 and Tier 4 not meeting the financial parameters of SFB and UNB, respectively, the following modifications are recommended to give more operational freedom to these banks, subject to banks meeting the suggested regulatory requirement of CRAR and net worth: i) Housing Loan -

The maximum limit on housing loans may be prescribed as a percentage of Tier 1 capital, subject to RBI-prescribed monetary ceiling for Tier 1 UCBs (but higher than the present ceiling) and respective Board of Directors-approved ceiling for Tier 2 UCBs. -

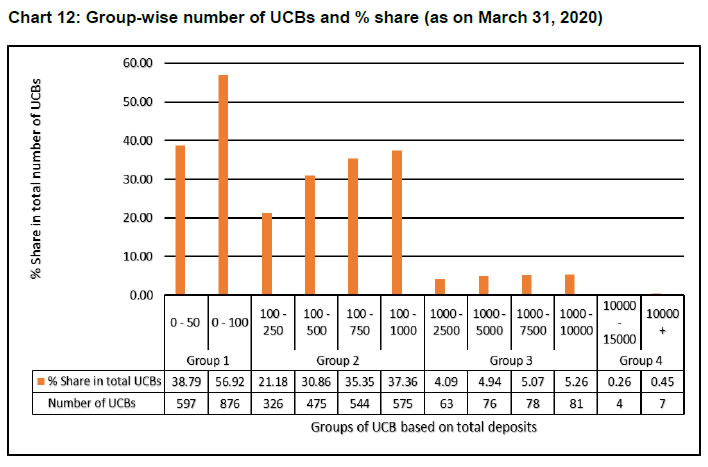

For Tier 2 UCBs, the risk weight on housing loans may be prescribed based on size of the loan and loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, in line with SCBs. ii) Loan against Gold Ornaments with Bullet Repayment Option -

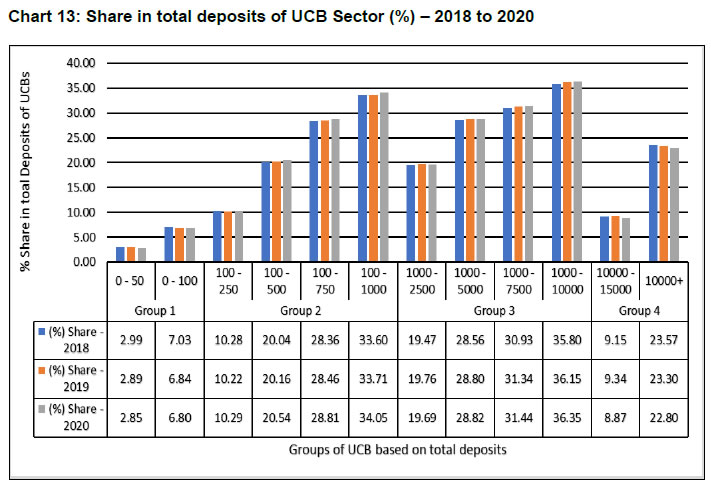

The maximum limit on loan against gold ornaments extended on bullet repayment terms may be prescribed as a percentage of Tier 1 capital, subject to suitable LTV ratio. -

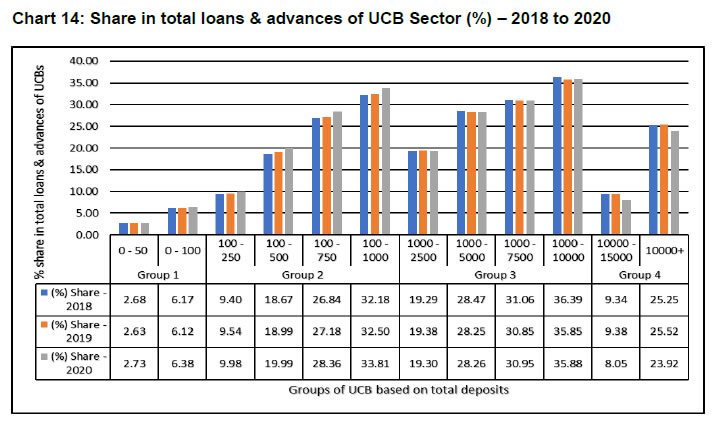

There may be an RBI-prescribed ceiling (higher than the present ceiling) for Tier 1 UCBs and respective Board of Directors-approved ceiling for Tier 2 UCBs. iii) Unsecured Advances -

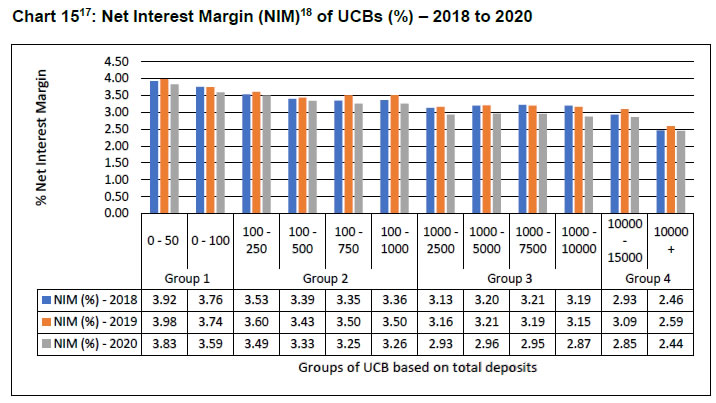

For banks in Tier 1 and 2, the maximum limit on individual unsecured loans may be linked to Tier-I capital, subject to a suitable upper cap for Tier 1 banks. Tier 2 banks may have a Board-approved ceiling. -

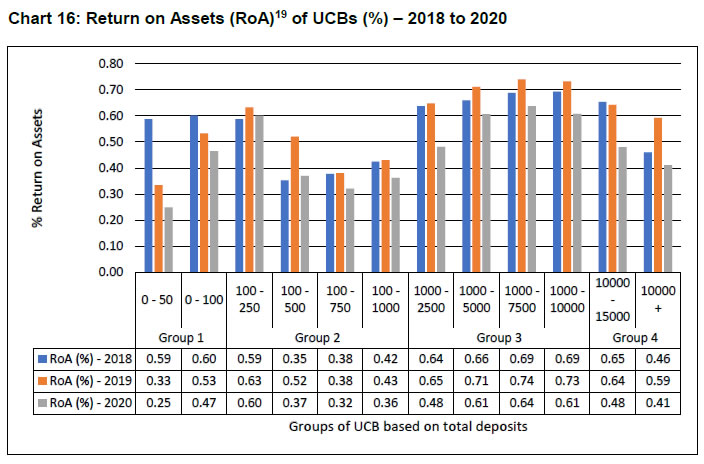

The present aggregate limit on unsecured advances, i.e., 10 per cent of total assets may continue. However, the UCBs may be allowed to have a higher limit with the approval of their Boards and subject to the condition that the loans exceeding the aforesaid 10 per cent limit must qualify to be classified as PSL. iv) For UCBs in Tier 2, the limit on exposure to various sectors may be removed (on par with concentration risk); additional standard asset provisioning may be imposed on exposure to a single sector beyond a specified percentage of the loan portfolio (say 20 percent). (Para 6.7.2) G. Computation of Tier I Capital Revaluation Reserve may be considered for inclusion in Tier I capital, subject to applicable discount on the lines of scheduled commercial banks. (Para 6.7.3.2) H. Umbrella Organization -

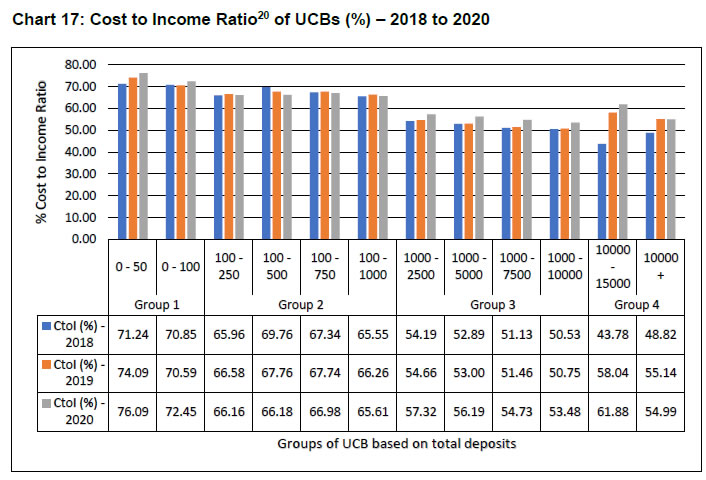

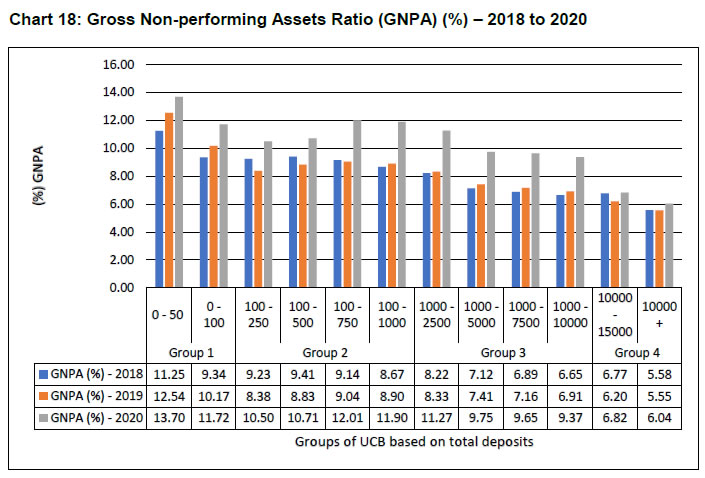

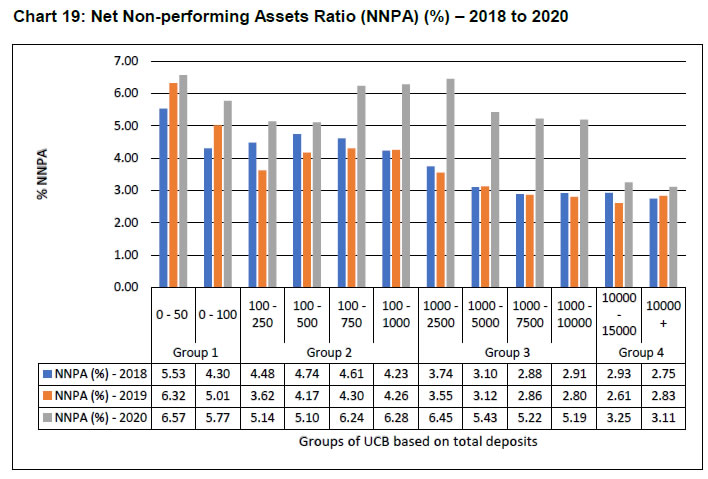

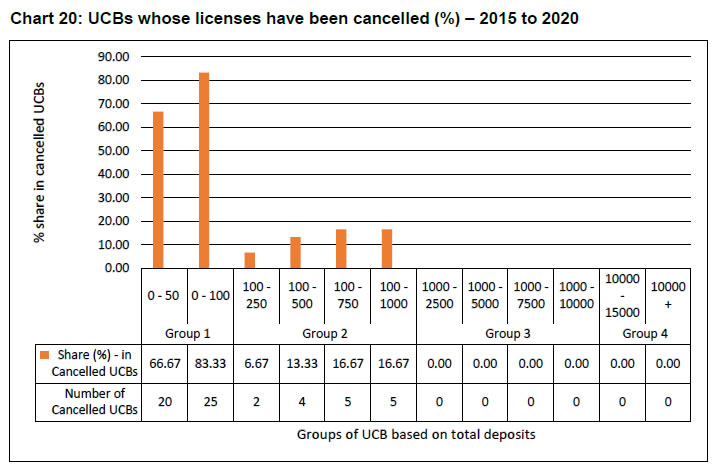

The UO is expected to play a crucial role in the strengthening of the sector. For that, it must be a financially strong organization with adequate capital and a viable business plan. The minimum capital for the UO should be ₹300 crore with CRAR and regulatory framework akin to the largest segment of NBFCs. It must be evaluated for quality of internal controls as it will also play the role of an SRO. -

In the long run, the UO may take up the role of a Self-Regulatory Organization (SRO) for smaller UCBs, where the UO could run an independent audit/inspection and supervisory division that may conduct both offsite and onsite supervision. Moreover, the membership of the UO could be opened to all types of co-operatives. While financial co-operatives would use most of the services of the UO, the non-financial co-operatives could use certain specific services provided by it, such as wallet services, cash management services and restricted/regulated access to payments and remittance systems. The contribution that the members make to the UO may, inter alia, be in the nature of share capital which will be permanently with the UO. It will have incremental membership with new members joining the UO, possibly at a premium that may be decided from time to time. -

Once the UO stabilizes, it may explore the possibilities of converting into universal bank and offer value-added services on behalf of its member banks. With suitable structural flexibility to operate as a bank, the UO can be owned by the co-operative institutions even if it is a joint stock company, which may encourage the smaller UCBs to become an extended arm of such a bank. -

Once the COR is issued and the UO commences its business, the RBI could consider providing a one-time grant to the UO for a specific objective tied to providing IT support to its member banks. Since aggregation of IT services will be a financial inclusion enabler and can also contribute to system-stability through standardisation of the IT interface, RBI’s financial support to the UO would be justifiable. (Para 6.7.4) I. Capital Instruments -

Amendments to BR Act empowering the RBI to declare certain securities issued by UCBs as covered under the Securities Contract Regulation Act to facilitate their listing and trading in a recognised stock exchange may be made. Till such time, the RBI may consider allowing banks in Tier 3 and 4, having the necessary technology and wherewithal, to issue shares at premium to persons residing in their areas of operation subject to certain conditions. (Para 7.13.1) -

UCBs may be permitted to grant advances to subscribers of PCNPS subject to the amount of loan being a limited multiple of the PNCPS subscribed to by the investor. The number of such borrowers and other nominal members having credit facility shall not exceed 20 percent of the total borrowing members of the UCB. In other words, the PNCPS subscribers who have borrowed from the bank will be akin to nominal members except that there shall not be a monetary ceiling of ₹1 lakh on the loans in their case but a limit in the form of a multiple of their subscription to PNCPS. (Para 7.13.2) -

For providing an avenue for persons to contribute to capital in the form of donations / grants-in-aid / contribution without accompanying voting rights, feasibility of issuing an alternate instrument, possibly in the form of Redeemable Preference Shares with very low coupon and maturity of 20 years could be considered. (Para 7.13.3.(ii)) 2.20 Recommendations on Supervisory Action Framework (SAF) and Consolidation -

SAF should follow a twin-indicator approach, i.e., it should consider only asset quality and capital measured through NNPA and CRAR instead of triple indicators at present. Additional provisioning suggested by the Inspecting Officers (IOs) should be adjusted from GNPA to arrive at assessed NNPA similar to the adjustments in Tier I capital done to arrive at assessed CRAR to determine whether SAF triggers are hit. The objective of the SAF should be to find a time-bound remedy to the financial stress of a bank. (Para 8.6.2 and 8.6.3.1). -

As hitherto, actions under the SAF may continue to be segregated into mandatory and discretionary. The action based on the suggested twin indicators may be taken by the RBI without reference to TAFCUB. However, there could be banks with other supervisory concerns like stress in profitability, governance-related concerns, etc., all of which call for further corrective action on the part of the banks. These may be considered for discretionary action in consultation with TAFCUB for banks in Tiers 1 and 2. (Para 8.6.3.2) -

All-inclusive directions should be treated on par with moratorium under Section 45 of BR Act and, if imposed, a bank should not continue thereunder beyond the time permitted to keep a bank under moratorium viz., three months extendable by a maximum of another three months. It is recommended that at some stage, the weak banks should be visited with a regulatory nudge to explore the possibility of voluntary merger or conversion into a non-banking society at an early stage with the clear understanding that in the absence thereof, the powers for mandatory resolution would be employed. (Para 8.6.3.3) -

In view of the powers derived from the recent amendment, the RBI may strive to begin the mandatory resolution process including reconstruction or compulsory merger as soon as a UCB reaches Stage III under the SAF. The RBI may also consider superseding the Board if the bank fails to submit voluntary merger / conversion proposal within the prescribed timeframe and take necessary steps to avoid undue flight of deposits once the news becomes public. (Para 8.6.3.4) -

A broad structure for SAF as recommended by the Committee is contained at Para 8.6.3.5. 2.21 Recommendations on Resolution of UCBs i) Under Section 45 of the BR Act, read with Section 56 thereof, RBI can prepare scheme of compulsory amalgamation or reconstruction of UCBs, like banking companies. This may be resorted to when the required voluntary actions are not forthcoming or leading to desired results. (Para 8.7.1.(ii)) ii) The action, other than voluntary responses by the banks may, inter alia, provide for one or more of the following: -

Compulsory amalgamation with another banking institution or a transfer of assets and liabilities to another financial institution. In such cases, the existing members of the transferor UCB may be disenfranchised for a period of five years. -

Reconstruction through reconstitution of the capital, assets, powers, rights, interests, privileges, liabilities, duties and obligations, change in Board of Directors, alteration of byelaws, etc. for giving effect to reconstruction. -

The amalgamation or reconstruction scheme may include reduction in the rights of creditors, including depositors and members of the bank; or payment in cash or in any other manner to depositors/creditors in respect of their entire claims or reduced claims, as the case may be. -

The section also offers flexibility to allot shares/long term debt instruments of the transferee bank (acquiring bank) to the depositors/creditors/members without reducing their claims. (Para 8.7.2) 2.22 Consolidation The minimum capital stipulation provides an embedded size to a UCB. The Committee feels that RBI should be largely neutral to voluntary consolidation except where it is suggested as a supervisory action. However, the RBI should not hesitate to use the route of mandatory merger to resolve UCBs that do not meet the prudential requirements after giving them an opportunity to come up with voluntary solutions. (Para 8.9.3) 2.23 Other Recommendations -

The existing regulatory neutrality in regard to the voluntary conversion of co-operative banks to joint stock companies as per the operating framework in place therefor may continue. (Para 6.2.2) -

To obviate difficulties for UCBs due to jurisdictional issues between the RBI and the concerned Registrars of Co-operative Societies (RCS) / Central Registrar of Co-operative Societies (CRCS), the RBI may consider clarifying the position appropriately to the concerned authorities. (Para 6.2.3) -

Since the recent amendments to the BR Act largely addresses the issues related to management and governance in UCBs with powers to RBI for prescribing ‘fit and proper criteria’ for directors and MD/CEO and requirement for minimum of 51 per cent of the directors having special qualification or experience, the extant guidelines related to constitution of Board of Management may be withdrawn. RBI should strictly enforce the new provisions of the BR Act with regard to Governance. A toolkit of appropriate regulatory responses besides enforcement action may be put in place. (Para 6.7.3.1) -

The Committee recommends that the UCBs should be included as eligible banks under the Government Schemes such as MUDRA, interest subvention/ subsidy scheme. UCBs should also be allowed to undertake Government business subject to them meeting the prescribed criteria. (Para 6.7.3.3) -

TAFCUB, as a forum for coordination should continue. While the mandatory action based on objective criterion under the SAF should be taken by the RBI, discretionary actions to address the deficiencies of other financial or non-financial nature, such as high GNPA, losses, governance issues, inefficiencies, weakness in systems and controls etc. in case of Tier 1 and 2 banks may be deliberated and appropriate supervisory action may be recommended by the TAFCUB. (Para 8.8.3) Chapter 3

GUIDING PRINCIPLES 3.1 The Committee considered it appropriate to deliberate on and articulate the guiding principles which informed its approach to the issues covered by the terms of reference in assimilating the feedback received during stakeholder consultations, directing the deliberations within the Committee, and finally for identifying most of the recommendations. These guiding principles are delineated below. 3.2 The Guiding Principles 3.2.1 Mutuality and Scale (i) The Committee considered the spirit of mutuality and co-operation at the member level and the principles of banking at the system and regulation level as one of the guiding principles. Traditionally, financial co-operatives have been community-based organisations – whether they are co-operative societies or credit unions – established on the principle of mutuality. Very much like the current day self-help groups, the principle of mutuality addressed the issue of lack of information (credit history or transaction trail) which is used in assessment of loans and leveraged on the knowledge of the community to assess risk. Since these institutions were envisaged as closed-loop institutions, their handshake with the external world was minimal. With the advent of technology and credit scoring systems, this needs to be redefined. Furthermore, a co-operative society leverages on co-operation whereas a bank leverages on capital. This friction is at the core of finding an optimal balance in adoption of the right approach to regulation and supervision of UCBs. The Committee feels that the regulatory framework needs to leverage the advantages that go with the co-operativeness of smaller UCBs in the form of proximity of the bank’s business operations to the customers, mutual trust, commonness of objectives leading to greater loyalty, benefit of informal channels of information, etc. 3.2.2 Approach regarding Statutory Provisions The legislative changes are taken as given and the Committee did not examine the feasibility or maintainability of the statutory provisions in the wake of the recent amendments to the BR Act and noted that by the construct of the legislation, the provisions of the BR Act would prevail, if they are in contradiction to the provisions of the Co-operative Societies’ Act under which a UCB is registered. The Committee took the view that it should instead work broadly based on the design principles that were necessary. The Committee, however, took note of some stakeholders’ viewpoint that the functionaries vested with the responsibility of the implementation of the Co-operative Societies laws may be prone to acting in a manner similar to the pre-amendment times. This could be a source for friction and cause complications in the smooth conduct of the UCBs’ banking business. Nonetheless, the Committee feels that this is primarily an administrative issue that needs to be resolved by mutual consultations and deliberations. 3.2.3 Implications of the Legislative Amendments - Conflict between the Provisions of the BR Act and the Co-operative Laws During the course of the deliberations with the stakeholders, the Committee was informed that as a result of the recent amendments to the BR Act, certain conflicts had arisen between the provisions of the amended BR Act and that of the various co-operative laws. This, for instance is important when it comes to sources of raising capital. The BR Act explicitly allows co-operative banks to issue shares at a premium, but it is silent on their redemption. Notwithstanding the rather paradoxical outcome, it would imply that if any co-operative societies’ legislation provides for redemption of shares only at par, then while a co-operative bank incorporated under that legislation can issue shares at a premium, it can redeem them only at par. However, for the reasons stated in (3.2.2) above, the Committee has let this be. 3.2.4 Shift in Legislative Approach to Co-operative Bank Regulation 3.2.4.1 Co-operative societies carrying on banking business were brought under the purview of the BR Act in the year 1966 by inserting a new Section 56 to the Act, which extended the provisions of the principal Act to them in the manner specified therein. Given the construct of section 56 of the Act prior to the recent amendments, the approach of the legislation was that even if a co-operative society was licensed as a bank, the underlying society had to be more governed by the Act under which it was set up rather than the Act under which it was licensed as a bank. It meant that many aspects of the working of the underlying society, even if they could have a fairly large bearing on the conduct of banking business, had to be seen through the lens of a co-operative society rather than that of a bank. Some such aspects were management, capital, audit, resolution, etc. The BR Act, post the recent amendments, reverses this philosophy to quite an extent and underscores the importance of regulating such entities as banks rather than as co-operative societies in the interest of depositors and in public interest. It, thus, marks a paradigm shift in the legislative approach with regard to regulation of co-operative societies carrying on banking business. 3.2.4.2 One of the major concerns with regard to regulation of UCBs, and perhaps the most important one, has been the absence of regulatory powers for RBI over their management, which made regulation of their banking business difficult insofar as RBI could hardly take any significant steps to bring about improvement in the quality of their management and governance. This and the other elements of what is called ‘dual control’, including, notably, absence of powers with regard to resolution, have significantly influenced RBI’s regulatory and supervisory approach towards UCBs. With a shift in the legislative framework consequent upon the recent amendments to the BR Act, it could be argued that the RBI now stands more empowered to regulate UCBs. 3.2.5 Heterogeneity Even as it recognized the need for and possibility of revisiting the current regulatory and supervisory template in the wake of the legislative changes, the Committee noted that any revised architecture will have to factor the extreme heterogeneity which the entities in the UCB sector display. The entities in the sector are quite heterogeneous in terms of size, geographical spread, business models, skill levels, technology adoption, clientele, etc. Even the laws bringing the underlying co-operative society into being and governing them are different as every state has its own Co-operative Societies’ Act with some such as Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, etc. having more than one, and there is a multi-state co-operative law as well. Given the heterogeneity, a ‘one size fits al’” regulatory approach creates constraints on resilience as well as growth of the banks. The framework should therefore strike an appropriate balance between putting in place tailor-made regulations that adequately recognize heterogeneity on the one hand, and avoiding multiple tiers of regulation to reduce complexity, on the other. In designing the approach, the Committee thought it fit to create, to the extent possible, the divide based on how closer or farther a bank’s functioning to co-operative principles is likely to be. 3.2.6 A Different Approach to Centrality of Capital 3.2.6.1 Banking is a complex business, and it was important to recognise the centrality of capital and the safety of public deposits. Therefore, entities undertaking banking business will be benefited by scale of operations. However, in case of UCBs, a dual approach to scale of operations will not only recognise the potential of the smaller entities to continue providing banking services while adhering more to co-operative principles and let the community derive the benefits thereof, but also delineate a framework for differentiated regulation. 3.2.6.2 At the base level, the Committee sees UCBs as the ones serving the underserved in a niche market and deepening the presence of formal banking. It also sees them as local institutions which aim to minimise the intermediation costs (low overheads, low costs of assessment) and thereby make it lucrative for both the savers and the borrowers. Using the above arguments, it is evident that co-operatives move away from the principles of mutuality as they grow in size or area of operations. The Committee believes that while one set of banks can be allowed to acquire scale through network, the others may be required to acquire scale on a stand-alone basis. This is further elaborated below: (i) Network-Based Scale While the spirit of co-operation based on the principle of mutuality could be maintained by small units that work within closed loop communities, the ecosystem has significantly changed and maintaining a connection with the complex financial world is important even for the smallest person as it opens up opportunities to access diverse range of financial products. In order to achieve this, the Committee kept the concept of an Umbrella Organisation (UO) as a pivotal point that would provide backstop arrangements for entities that continued to be small. The UO, when fully evolved, would provide the following backstop arrangements: -

Access to cloud-based technology, which could be used on a shared basis -

Access to payment systems, interchange and common branding for offering products based on technology (payments interface, cards) -

Access to other financial products that could be cross sold – insurance, mutual funds, pensions and other financial products -

Access to capital and liquidity support in case of stress to a particular member co-operative -