The growth of the Indian banking sector moderated further during 2013-14. Profitability declined on account

of higher provisioning on banks’ delinquent loans and lacklustre credit growth. The financial health of urban and

rural co-operatives indicated divergent trends in terms of key indicators. While urban co-operative banks (UCBs)

exhibited improved performance, the performance of primary agriculture credit societies (PACS) and long term

rural credit co-operatives remained a matter of concern with a further increase in their losses coupled with a

deterioration in asset quality. While the asset size of the non-banking financial companies (non-deposit taking

systemically important) showed an expansion, asset quality deteriorated further during the period of review.

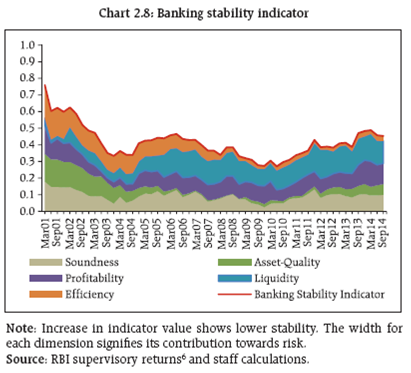

The banking stability indicator suggests that overall risks to the banking sector remained unchanged during the

first half of 2014-15. In individual dimensions, though the liquidity position improved in the system, concerns

remain on account of deterioration in asset quality along with weakened soundness. The profitability dimension

of the indicator showed an improvement but it remained sluggish. The stress tests suggest that the asset quality

of banks may improve in the near future under expected positive developments in the macroeconomic conditions

and banks may also be able to meet expected losses with their existing levels of provisions. However, the asset quality

of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) may worsen from the current level if the macroeconomic conditions

deteriorate drastically and banks are likely to fall short in terms of having sufficient provisions to meet expected

losses under adverse macroeconomic risk scenarios.

Analysis of the interconnectedness indicates that the size of the interbank market in relation to total banking

sector assets has been on a steady decline. However, contagion analysis with top five most connected banks reveals

that the banking system could potentially lose significant portion of its total Tier-I capital under the joint solvencyliquidity

condition in the event of a particular bank triggering a contagion.

2.1 Given the sluggish demand for credit and

concerns about asset quality, the Indian banking

sector experienced relatively lower growth and dip in

profitability in 2013-14. Scheduled commercial banks

(SCBs) showed a moderation in balance sheet growth

and a fall in net profits, while the trends were

divergent amongst other banking institutions with

urban co-operative banks and short-term rural credit

co-operative institutions other than primary

agriculture credit societies (PACS) showing an

improvement in growth as well as health. Long-term

credit co-operative institutions, however, continued

to be a weak spot within the banking sector.

2.2 Data used in this report are based on audited

accounts of banks for the year ended 31 March 2014

as well as supervisory returns till 30 September 2014.

The annual accounts include foreign operations of

banks, whereas, the supervisory returns covered only their domestic operations. The detailed data on

balance sheets as well as income and expenditure of

SCBs, regional rural banks, local area banks, urban

co-operative banks and rural credit co-operatives are

available in the ‘Statistical Tables Relating to Banks

in India 2013-14’ (www.rbi.org.in).

Scheduled commercial banks

2.3 This section discusses the health and

performance of SCBs on the basis of their:

(i) consolidated operations covering their domestic as

well as overseas operations during 2013-2014 (as

reported through their audited accounts) and

(ii) domestic operations during the first half of

2014-15 (based on supervisory returns).

Performance

Consolidated operations

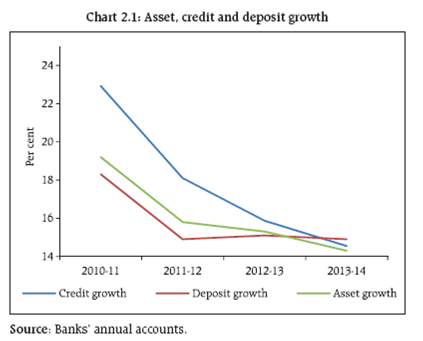

2.4 The consolidated balance sheet of SCBs in

2013-14 registered a decline in growth in total assets and credit for the fourth consecutive year (Chart 2.1).

This decline could be attributed to a variety of factors

ranging from slower economic growth, de-leveraging,

persistent pressure on asset quality leading to

increased risk aversion among banks and also

increasing recourse by corporates to non-bank

financing including commercial papers and external

commercial borrowings.

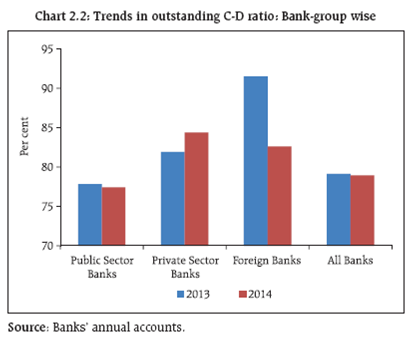

2.5 With both credit and deposit growth more or

less same, the outstanding credit to deposit (C-D) ratio

at the aggregate level remained unchanged at around

79 per cent (Chart 2.2).

Domestic operations

Credit and deposit growth

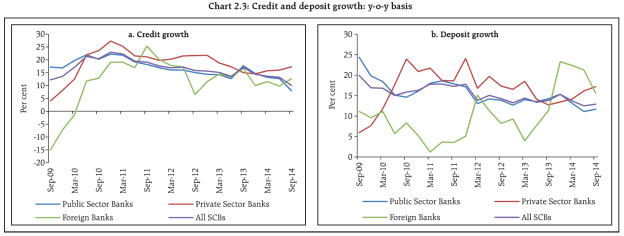

2.6 Credit growth on a y-o-y basis continues to

decline and recorded low growth at 10.0 per cent as

of September 2014, with public sector banks (PSBs)

underperforming the rest with a growth of 7.9 per

cent. Growth in deposits also declined to 12.9 per cent

as of September 2014 from 13.7 per cent as of March

2014 (Chart 2.3).

Soundness

Capital adequacy

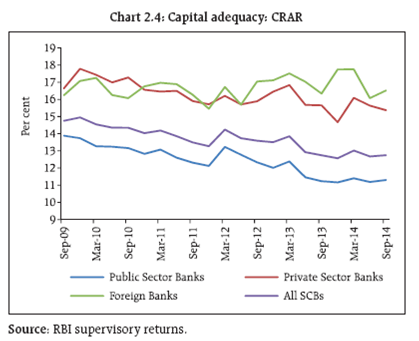

2.7 Between March and September 2014 the total

capital and risk weighted assets (RWA) of SCBs

increased by 1.9 per cent and 4.1 per cent respectively.

This has resulted in decline in the capital to risk

weighted assets ratio (CRAR) from 13.0 per cent to

12.8 per cent (Chart 2.4).

Leverage

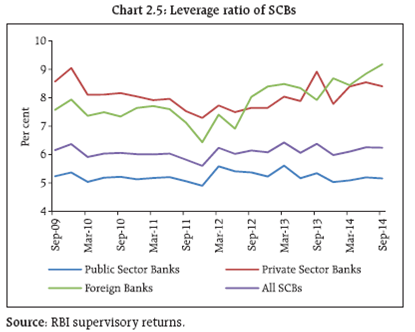

2.8 The Tier I leverage ratio1 was 6.2 per cent in

September 2014. In the case of PSBs, it marginally

improved to 5.2 per cent in September 2014 from 5.1

per cent in March 2014 (Chart 2.5).

Asset quality

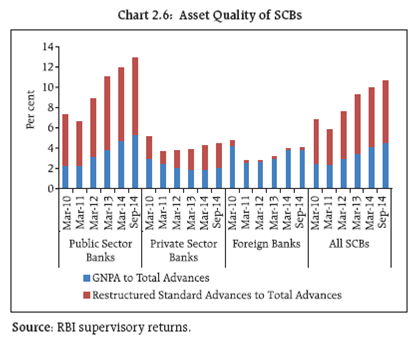

2.9 The gross non-performing advances (GNPAs)

of SCBs as a percentage of the total gross advances

increased to 4.5 per cent in September 2014 from 4.1

per cent in March 2014. The net non-performing

advances (NNPAs) as a percentage of total net advances

also increased to 2.5 per cent in September 2014 from

2.2 per cent in March 2014. Stressed advances2

increased to 10.7 per cent of the total advances from

10.0 per cent between March and September 2014.

PSBs continued to record the highest level of stressed

advances at 12.9 per cent of their total advances in

September 2014 followed by private sector banks at

4.4 per cent (Chart 2.6).

2.10 At a more granular level, share of stressed

advances in total advances increased in the case of 46

SCBs (accounting for around 88 per cent of total loan

portfolios of SCBs) between March and September 2014 (Table 2.1). There are 20 banks which have higher

share in the total stressed advances of all SCBs than

their share in the total advances of SCBs. These 20

banks together have 43 per cent of the total SCB loans

and contribute around 60 per cent of the total stressed

advances of the banking system.

Table 2.1: Changes in the stressed advances ratio : March - September 2014 |

|

No. of

Banks |

Share in Total

Advances of all

SCBs (in per cent) |

Increase in Stressed Advances Ratio |

46 |

88.2 |

Decline in Stressed Advances Ratio |

25 |

5.9 |

No Change in Stressed Advances Ratio |

18 |

5.9 |

Total |

89 |

100.0 |

Source: RBI supervisory returns. |

2.11 Five sub-sectors: infrastructure, iron and steel,

textiles, mining (including coal) and aviation, had

significantly higher levels of stressed assets and thus

these sub-sectors were identified as ‘stressed’ sectors

in previous FSRs. These five sub-sectors had 52 per

cent of total stressed advances of all SCBs as of June

2014, whereas in the case of PSBs it was at 54 per cent

(Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: Share of stressed advances in total loan portfolio |

(Per cent) |

Sub-sector |

|

All SCBs |

PSBs |

Mar-13 |

Mar-14 |

Jun-14 |

Mar-13 |

Mar-14 |

Jun-14 |

Mining |

Share in Total Advances of SCBs |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

Share in Total Stressed Advances of SCBs |

0.6 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

Iron and Steel |

Share in Total Advances of SCBs |

4.9 |

4.8 |

4.8 |

5.7 |

5.5 |

5.6 |

Share in Total Stressed Advances of SCBs |

8.2 |

10.8 |

10.2 |

8.7 |

11.2 |

10.6 |

Textiles |

Share in Total Advances of SCBs |

3.7 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

Share in Total Stressed Advances of SCBs |

7.5 |

7.7 |

7.2 |

7.5 |

7.8 |

7.4 |

Infrastructure |

Share in Total Advances of SCBs |

14.6 |

14.4 |

14.8 |

16.8 |

16.5 |

17.1 |

Share in Total Stressed Advances of SCBs |

28.8 |

29.4 |

30.7 |

29.5 |

30.2 |

31.9 |

Aviation |

Share in Total Advances of SCBs |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

Share in Total Stressed Advances of SCBs |

3.9 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

4.3 |

3.6 |

3.4 |

Total |

Share in Total Advances of SCBs |

24.4 |

23.9 |

24.2 |

28.0 |

27.2 |

28.0 |

Share in Total Stressed Advances of SCBs |

48.9 |

52.0 |

52.0 |

50.5 |

53.7 |

54.0 |

Source: RBI supervisory returns. |

2.12 The data on exposure to infrastructure as of

September 2014 shows that SCBs’ exposure to the

sector rose further to 15.6 per cent of their total loans.

Exposure to the energy segment largely comprising

of electricity, oil and gas constituted the major portion

(around 58 per cent) of banks’ aggregate exposure to

infrastructure sectors, followed by transport (around

21 per cent) and telecommunications (around 10 per

cent). Among bank groups, exposure of PSBs to

infrastructure stood at 17.5 per cent of their gross advances as of September 2014. This was significantly

higher than that of private sector banks (at 9.6 per

cent) and foreign banks (at 12.1 per cent).

Profitability

Consolidated operations

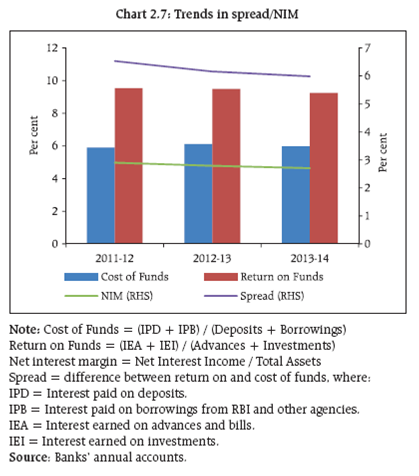

2.13 During 2013-14, the growth in net profits of

SCBs, which had been on a declining trend since

2011-12, turned negative. SCBs as a whole reported

net profits of about `809 billion, indicating decline

by 11.3 per cent compared to previous year. This

decline in net profits was primarily the result of higher

provisioning on banks’ delinquent loans which

registered an increase of nearly 34 per cent coupled

with growth in the interest expenses of around 12

per cent during the year. This in turn impacted their

return on assets (RoA) and return on equity (RoE)

(Table 2.3). Their spread and net interest margin (NIM)

also witnessed a decline (Chart 2.7).

Table 2.3: Return on assets and return on

equity of SCBs: Bank group-wise |

(Per cent) |

Sr. No. |

Bank Group/Year |

Return on Assets |

Return on Equity |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

1 |

Public sector banks |

0.80 |

0.50 |

13.24 |

8.47 |

2 |

Private sector banks |

1.63 |

1.65 |

16.46 |

16.22 |

3 |

Foreign banks |

1.92 |

1.57 |

11.53 |

9.02 |

|

All SCBs |

1.04 |

0.81 |

13.84 |

10.68 |

Notes: Return on Assets = Net profit/Average total assets.

Return on Equity = Net profit/Average total equity.

Source: Annual accounts of respective banks. |

Domestic operations

2.14 After contraction in the profit after tax (PAT)

during the financial year 2013-14, SCBs recorded

positive growth in PAT at 10.0 per cent in September

2014 due to the significantly lower growth in

provisioning and write-offs. The RoA of all SCBs

remained at 0.8 per cent as of September 2014,

whereas, RoE of SCBs improved to 9.9 per cent as of

September 2014 from 9.5 per cent as of March 2014

(Table 2.4).

Table 2.4: Profitability of SCBs |

(Per cent) |

|

Return on Assets |

Return on Equity |

PAT Growth |

Earnings Before

Provisions & Taxes-Growth |

Net Interest

Income-Growth |

Other Operating

Income-Growth |

Sep-11 |

1.0 |

12.4 |

6.3 |

11.2 |

16.8 |

4.1 |

Mar-12 |

1.1 |

13.4 |

14.6 |

15.3 |

15.8 |

7.4 |

Sep-12 |

1.1 |

13.2 |

24.5 |

13.2 |

12.9 |

12.4 |

Mar-13 |

1.0 |

12.9 |

12.9 |

9.9 |

10.8 |

14.4 |

Sep-13 |

0.8 |

10.2 |

-9.7 |

12.8 |

11.6 |

30.5 |

Mar-14 |

0.8 |

9.5 |

-14.1 |

9.5 |

11.7 |

16.6 |

Sep-14 |

0.8 |

9.9 |

10.0 |

7.0 |

9.7 |

4.3 |

Note: RoA and RoE are annualised figures, whereas growth on a y-o-y basis.

Source: RBI supervisory returns. |

Risks

2.15 As per the Banking Stability Indicator (BSI),3

risks to the banking sector have not changed much

since the publication of the previous FSR.4 The BSI

showed a continuous increase in vulnerability in the

banking sector over the past few years. The factors

contributing towards increase in risks, in the order

of their share, are liquidity, profitability, soundness

and asset quality. Though the liquidity position

improved in the system during March and September

2014, concerns remain over deterioration in asset

quality and soundness.5 Profitability improved but

remained sluggish (Charts 2.8 and 2.9).

Stress tests

Macro stress test: Credit risk

2.16 The resilience of the Indian banking system

against macroeconomic shocks was tested through a

series of macro stress tests for credit risk at the

system, bank group and sectoral levels. These tests

encompass assumed risk scenarios incorporating a

baseline and two adverse macroeconomic scenarios

representing medium and severe risks (Table 2.5). The

adverse scenarios were derived based on up to 1 standard deviation (SD) for medium risk and 1.25 to

2 SD for severe risk (ten years historical data).

Table 2.5: Macroeconomic scenario assumptions7 |

(per cent) |

FY |

|

Baseline |

Medium

Stress |

Severe

Stress |

2014-15* |

Real GDP Growth |

5.5 |

4.0 |

2.6 |

Gross Fiscal Deficit |

4.1 |

4.9 |

5.7 |

CPI (Combined) Inflation |

7.4 |

8.9 |

10.4 |

Weighted Average Lending Rate |

12.1 |

12.6 |

13.0 |

Merchandise Exports to GDP Ratio8 |

15.5 |

14.3 |

13.1 |

2015-16 |

Real GDP Growth |

6.3 |

4.1 |

2.1 |

Gross Fiscal Deficit |

3.6 |

4.8 |

6.0 |

CPI (Combined) Inflation |

7.2 |

9.5 |

11.6 |

Weighted Average Lending Rate |

12.1 |

12.8 |

13.5 |

Merchandise Exports to GDP Ratio |

16.5 |

14.7 |

13.0 |

* Average number for the last two quarters of FY 2014-15. |

System level credit risk

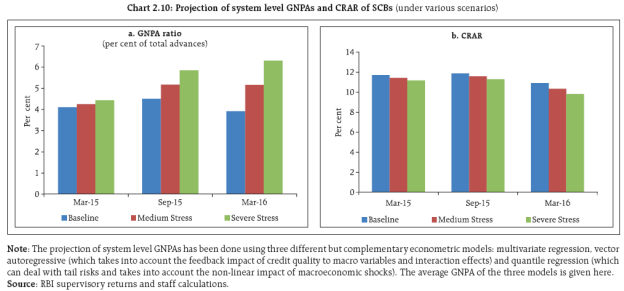

2.17 The macro stress tests for credit risk suggest

that under the baseline scenario, which assumes

improvement in the overall macroeconomic scenario

during the next financial year, the GNPA ratio of all

SCBs may decline to 4.0 per cent by March 2016 from

4.5 per cent as at end September 2014. However, if

macroeconomic conditions deteriorate, the GNPA ratio

may increase further and under a severe stress scenario could rise to around 6.3 per cent by March

2016. Under such a severe stress scenario, the system

level CRAR of SCBs could decline to 9.8 per cent by

March 2016 from 12.8 per cent in September 2014

(Chart 2.10).

Bank group level credit risk

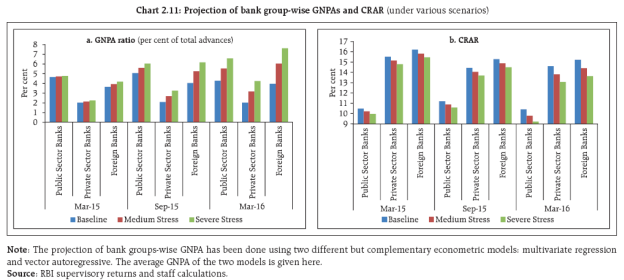

2.18 Under the assumed baseline scenario of

improved macroeconomic conditions, the asset

quality of public sector banks is expected to improve,

but they will continue to carry the highest GNPA ratio

among the bank groups (Chart 2.11).

2.19 Under a severe stress scenario, PSBs may

record the lowest CRAR of around 9.2 per cent by

March 2016 (as against 11.3 per cent in September

2014), close to the minimum regulatory capital

requirement of 9 per cent (Chart 2.11).

Sectoral credit risk

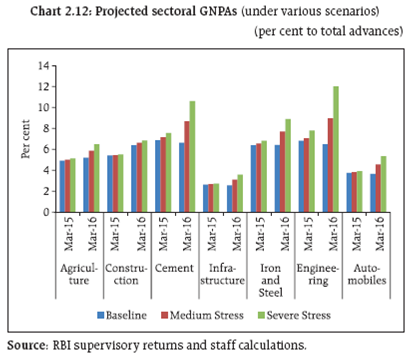

2.20 A macro stress test of sectoral credit risk

revealed that under a severe stress scenario, among

seven select sectors the engineering sector is expected

to register the highest GNPA ratio at 12.0 per cent by

March 2016 followed by the cement sector (10.6 per

cent) (Chart 2.12).

Estimation of losses9 for credit risk: Provisioning

and capital adequacy

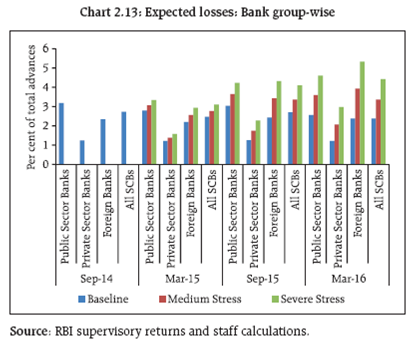

2.21 Due to secular deterioration in their asset

quality, SCBs’ expected loss (EL) continues to rise

but might decline in the second half of 2015-16 if

the assumed improvements in macroeconomic

conditions materialise. The current level of

provisions10 of various bank groups – public sector

banks, private sector banks and foreign banks as a

proportion of their respective total advances as of

September 2014 were at 3.2 per cent, 1.9 per cent

and 3.9 per cent respectively. Among the bank

groups, PSBs had the highest expected loss at 3.2 per

cent of their total advances as of September 2014.

Though they may meet the expected losses under

baseline scenarios they are likely to fall short in

terms of having sufficient provisions to meet

expected losses (EL) under adverse macroeconomic

risk scenarios11 (Chart 2.13).

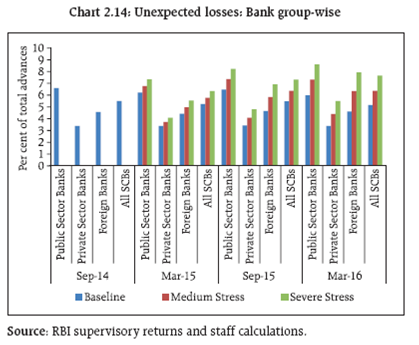

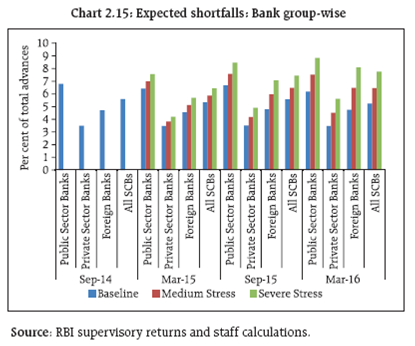

2.22 The estimated unexpected losses (UL) and

expected shortfalls (ES) arising from the credit risk of

various bank groups even under severe macroeconomic

stress conditions are expected to be much lower than

the present level of total capital (Tier-I plus Tier-II)

maintained by them. Public sector banks, private

sector banks and foreign banks maintained total

capital at the level of 12.5 per cent, 21.4 per cent and

36.0 per cent of total advances respectively as of

September 2014 (Charts 2.14 and 2.15).

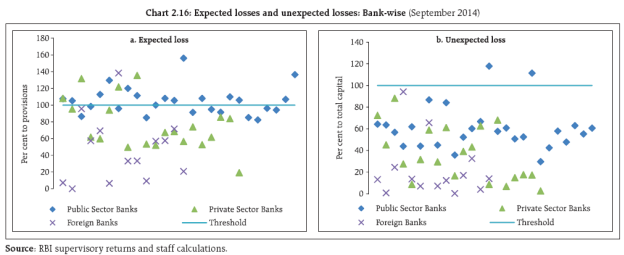

2.23 The bank-wise12 estimation of EL and UL

arising from credit risk shows that 20 banks (mostly

PSBs) were unable to meet their expected losses with

their existing provisions. These banks had a 29.8 per

cent share in the total advances of the select 60 banks.

On the other hand, there were only two banks (with

2.0 per cent share in total advances of the select banks)

which were expected to have higher unexpected

losses than the total capital (Chart 2.16).

Sensitivity Analysis: Bank Level13

2.24 A number of single factor sensitivity stress

tests (top-down) were carried out on select SCBs (60

banks accounting for 99 per cent of the total banking

sector assets) to assess their vulnerabilities and

resilience under various scenarios. The resilience of

commercial banks with respect to credit, interest rate

and liquidity risks was studied through the top-down

sensitivity analysis by imparting extreme but

plausible shocks. The results are based on September

2014 data.14

Top-down stress tests

Credit risk

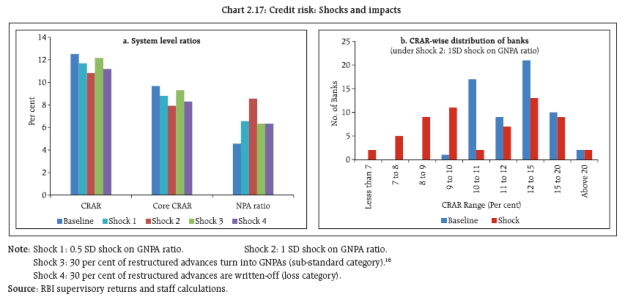

2.25 The impact of different static credit shocks

for banks as on September 2014 shows that the system

level stressed CRAR remained above the required

minimum of 9 per cent (Chart 2.17). Capital losses at the system level could be about 15 per cent in the

case of a severe shock of 1 SD15 (shock 2), while the

impact on banks’ profits would be more severe wiping

out their annual profits. The stress test results further

show that 16 banks, mostly PSBs, sharing about 28

per cent of SCBs’ total assets, would fail to maintain

required CRAR if GNPA increases under shock 2

assumptions. For 7 banks, the CRAR may even go

below the level of 8 per cent.

Credit concentration risk

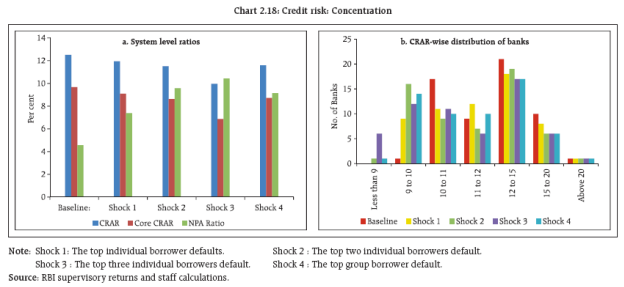

2.26 Stress tests on the credit concentration risk

of banks show that the impact under various stress

scenarios was significant for six banks, which account

for 8 per cent of the assets, with their CRAR falling

below 9 per cent. Capital losses could be around 5

per cent, 9 per cent and 14 per cent at the system

level under the assumed scenarios of default of the

top one, two and three individual borrowers respectively. Capital losses17 could be around 9 per

cent at the system level under the assumed scenarios

of default of the top group borrower. The impact on

profit before tax (PBT) could be as high as 202 per

cent with a minimum of 73 per cent under the same

scenarios. The direct impact on CRAR at the system

level under the assumed scenarios of default of the

top individual borrower, the top two individual

borrowers, the top three individual borrowers and

default by the top group borrowers would be 56, 100,

254 and 94 basis points respectively. However, system

level CRAR will remain above 9 per cent under these

shocks (Chart 2.18).

Sectoral credit risk

2.27 Credit risk of exposure to a few important

sectors/industries was examined through sectoral

credit stress tests. The assumed shock was an

increase in GNPAs ratio by 5 percentage points in

each sector. The results of a sensitivity analysis

revealed that the shocks would significantly increase

system level GNPAs, with the most significant effect

of the single sector shock being in the real estate

(Table 2.6). The impact of the shock on capital ratios

was limited given that only a portion of the credit

portfolio was shocked. However, there could be a significant impact on banks’ profitability (profit

before tax).

Table 2.6: Credit risk: Sectors |

(Per cent) |

Sector level |

System level |

CRAR |

Tier-1

CRAR |

GNPA

Ratio |

Losses as

per cent

of capital |

Losses as

per cent

of profit |

Baseline: |

12.5 |

9.7 |

4.6 |

- |

- |

|

Share in Total

Advances |

GNPA Ratio of

the Sector |

Shock: 5 percentage points increase

in GNPAs in each sector |

Agriculture |

12.6 |

5.4 |

12.3 |

9.4 |

5.2 |

2.4 |

17.6 |

Power |

9.0 |

1.4 |

12.3 |

9.5 |

5.0 |

1.6 |

11.7 |

Real Estate |

17.4 |

4.6 |

12.2 |

9.3 |

5.4 |

3.3 |

24.5 |

Telecom |

1.6 |

4.8 |

12.5 |

9.6 |

4.6 |

0.3 |

2.3 |

All 4 Sectors (Agriculture + Power + Real Estate + Telecom) |

41.0 |

4.0 |

11.7 |

8.8 |

6.6 |

7.7 |

57.9 |

Priority Sector |

34.1 |

5.2 |

11.8 |

9.0 |

6.3 |

6.4 |

47.7 |

Source: RBI supervisory returns and staff calculations. |

Interest rate risk

2.28 The interest rate risk in the trading book

(direct impact on AFS and HFT portfolios of banks)

under various stress scenarios is manageable with

reduction in CRAR by 74 basis points at the system

level. This impact is due to parallel upward shift (2.5

percentage points) in the yield curve. Reduction in

CRAR was 82 basis points reported in the previous

FSR (June 2014) for the same shock. At the disaggregated

level, three banks that accounted for 5.1 per cent

assets are getting impacted adversely. The total capital

loss at the system level would be about 6.6 per cent.

The assumed shock of 2.5 percentage points parallel

upward shift in the yield curve on the HTM portfolio

of banks, if marked-to-market, would significantly

reduce the CRAR by about 261 basis points (the

previous FSR reported an impact of 280 basis points),

impacting 25 banks. The income impact on the

banking book18 of SCBs could be about 50 per cent of

their profit (before tax) under the assumed shock of

a parallel downward shift (2.5 percentage points) in

the yield curve.

Liquidity risk

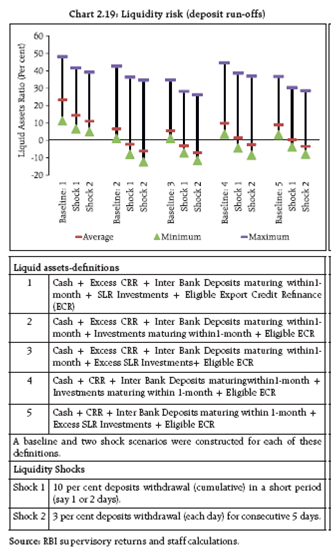

2.29 The liquidity risk analysis captures the impact

of assumed deposit run-off scenarios on banks. The

analysis used five definitions of liquid asset.19 As per

these definitions, liquid assets comprise of cash, CRR,

interbank deposits and investments in different

forms. Different liquid asset ratios20 were arrived at

using various definitions under the baseline scenario.

The stress scenarios were constructed to test the banks’ ability to meet a run on their deposits using

only their liquid assets. The analysis shows that

though there was liquidity pressure under the stress

scenarios, banks could withstand sudden and

unexpected withdrawals by depositors under assumed

shocks with the help of their statutory liquidity ratio

(SLR) investments (Chart 2.19).

2.30 Another liquidity risk analysis based on the

unutilised portion of credit lines which are sanctioned/

committed/guaranteed (taking into account the

undrawn working capital sanctioned limit, undrawn

committed lines of credit and letters of credit and

guarantees) was carried out to focus on banks’ ability

to fulfil the additional demand for credit. Banks were

required to meet the demand using their cash

balances, excess CRR, short term interbank deposits

(one month maturity), excess SLR and eligible export

credit refinance (ECR). The major impact was due to

the utilisation of undrawn working capital limits and

around 12 small banks were unable to meet the credit

requirements of their customers using existing liquid

assets (shock1). However, the number of impacted

banks was much lower at six, if only a portion (50 per

cent) of undrawn sanctioned working capital was

assumed to be used by the customers (Table 2.7).

Table 2.7: Liquidity risk: Utilisation of undrawn limits/

devolvement of contingencies |

|

System Level |

Impacted Banks |

Size of

Unutilised

Credit

(% to O/s

Advances) |

Liquid

Assets

Ratio

(%) |

Number

of Banks

with Deficit

Liquidity

after shock |

Deposit

Share

(%) |

Asset

Share

(%) |

Liquid assets: Cash, excess CRR, interbank deposits maturing 1-month, excess SLR, ECR |

Baseline |

- |

5.6 |

- |

- |

- |

Shock 1 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

12 |

8.5 |

9.5 |

Shock 2 |

1.4 |

4.4 |

6 |

4.2 |

5.0 |

Shock 3 |

0.4 |

5.0 |

2 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

Shock 4 |

0.2 |

5.1 |

1 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

Shock 5 |

0.4 |

5.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Note: Liquidity Shocks

Shock 1: Undrawn Sanctioned Limit - Working Capital - Fully Used

Shock 2: Undrawn Sanctioned Limit - Working Capital - Partially Used (50

per cent)

Shock 3: Undrawn Committed Credit Lines to Customers - Fully Demanded

Shock 4: Undrawn Committed Credit Lines to Customers - Partially

Demanded (50 per cent)

Shock 5: Letters of Credit/Guarantees given to Customers - Devolvement

Source: RBI supervisory returns and staff calculations. |

Bottom-up stress tests: Derivatives portfolios of

banks

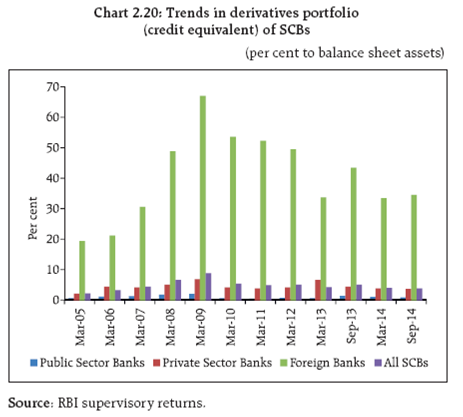

2.31 The derivatives portfolios of banks have

relatively shrunk in the recent period. The credit

equivalent of the derivatives portfolio is about 4 per

cent of balance sheet assets. However, the size of the

derivatives portfolio was quite significant for foreign

banks at 34 per cent of their balance sheet assets in

September 2014 (Chart 2.20).

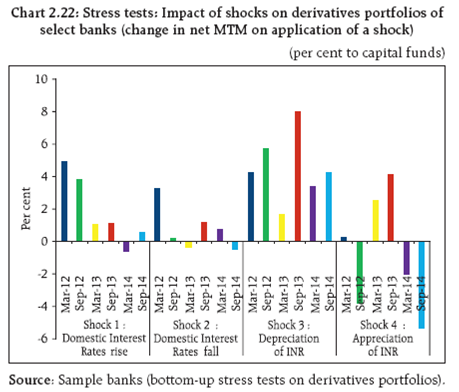

2.32 A series of bottom-up stress tests (sensitivity

analyses) on derivative portfolios were conducted

for select sample banks,21 with the reference date as

on 30 September 2014. The banks in the sample

reported the results of four separate shocks on

interest and foreign exchange rates. The shocks on

interest rates ranged from 100 to 250 basis points, while 20 per cent appreciation/depreciation shocks

were assumed for foreign exchange rates. The stress

tests were carried out for individual shocks on a

stand-alone basis.

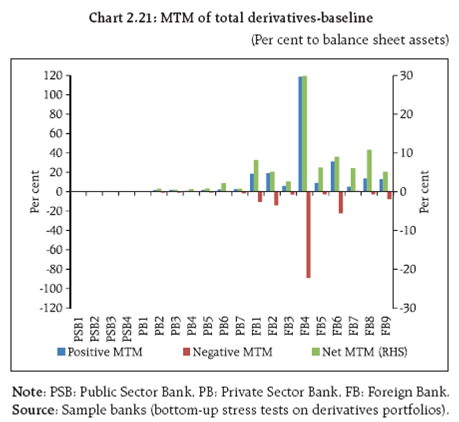

2.33 In the sample, the impact of mark-to-market

(MTM) of the derivatives portfolios for banks as a

proportion to their balance sheet assets as of

September 2014 varied with PSBs and PBs registering

small values, while foreign banks had relatively large

ratios. The banks had positive net MTM in September

2014 (Chart 2.21).

2.34 The stress test results showed that the average

net impact of interest rate shocks on sample banks

was not very high. However, foreign exchange shock

scenarios showed relatively higher impacts on banks

(Chart 2.22).

Regional rural banks

Balance sheet operations

2.35 Regional rural banks (RRBs) maintained stable

growth in assets around 16 per cent during 2013-14.

Major sources of growth were borrowings and capital

infusion by NABARD and sponsor banks on the

liabilities side and loans and advances on the assets

side.

Profitability

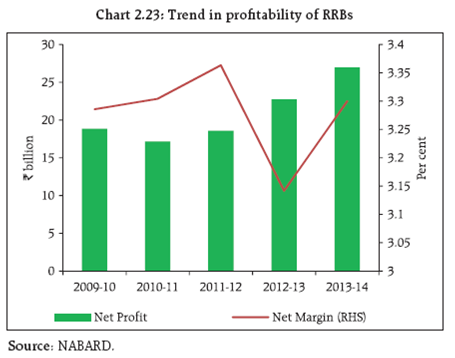

2.36 As per the provisional results, all the 57 RRBs

reported profits in 2013-14 with their net profits going

up by 18.5 per cent during the year. Net margin (net

interest income as per cent of average total assets)

also recovered from previous year (Chart 2.23).

Local area banks

Balance sheet operations and profitability

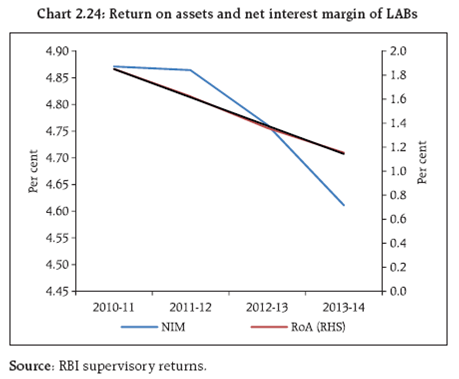

2.37 Four local area banks (LABs) are currently

operational. During 2013-14, they witnessed an asset

growth of 20 per cent. The decline in net profits by

over 21 per cent, can be attributed to growth in

interest expenses outpacing the increase in their

incomes (Chart 2.24).

Urban co-operative banks

Balance sheet operations

2.38 The balance sheets of urban co-operative

banks (UCBs) showed stable growth in 2013-14

(Chart 2.25). Growth in liabilities was driven by an

increase in their other liabilities and deposits.

Following consolidation, the number of UCBs came

down marginally to 1,589 in 2013-14 from over 1,600

a year ago.

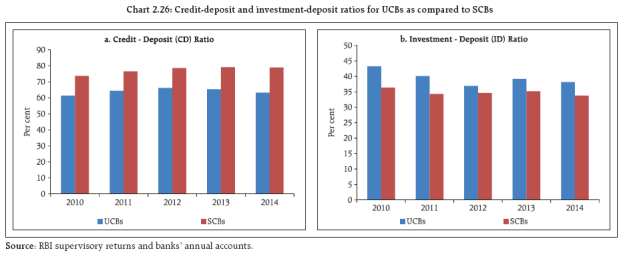

2.39 In 2013-14 UCBs’ C-D ratio declined by about

2 percentage points and the investment-deposit ratio

also showed a small contraction (Chart 2.26).

Profitability

2.40 Net profits of UCBs increased by 31 per cent

during 2013-14 as compared to a decline of 25 per

cent in the previous year. Although the growth in both

income and expenditure decelerated during the year,

the sharp contraction in provisions, contingencies

and taxes resulted in an increase in their net profits.

Consequently, RoA and RoE of UCBs improved to 0.9

per cent and 9.0 per cent, respectively, during the year

from 0.8 per cent and 7.2 per cent during 2012-13.

Scheduled urban co-operative banks

Performance

2.41 At the system level,22 CRAR of scheduled

urban co-operative banks (SUCBs) improved to 12.7

per cent as of September 2014 from 12.4 per cent as

of March 2014. However, at a disaggregated level,

seven banks failed to maintain the minimum required

CRAR of 9 per cent. The asset quality of SUCBs,

measured in terms of GNPAs, deteriorated and their

provision coverage ratio declined significantly

(Table 2.8).

Table 2.8: Select financial soundness indicators of SUCBs |

(per cent) |

Financial Soundness Indicators |

Mar-14 |

Sep-14 |

CRAR |

12.4 |

12.7 |

Gross NPAs to Gross Advances |

5.5 |

7.4 |

Return on Assets (annualised) |

0.7 |

0.9 |

Liquidity Ratio |

35.1 |

35.5 |

Provision Coverage Ratio (PCR) |

71.4 |

53.7 |

Note: 1. Data are provisional.

2. Liquidity Ratio = (Cash + due from banks + SLR

investment) / Total Assets * 100.

3. PCR is compiled as ‘NPA provisions held as per cent of Gross

NPAs’.

Source: RBI supervisory returns. |

Stress tests

Credit risk

2.42 A stress test for assessing credit risk was

carried out for SUCBs using the provisional data as of

September 30, 2014. The impact of credit risk shocks

on CRAR of SUCBs was observed under four different

scenarios.23 The results showed that except under the

extreme scenario (1SD increase in GNPAs which are

classified as loss advances), the system level CRAR of

SUCBs remained above the minimum regulatory

required level, though individually a large number of

banks (28 of the 50 banks under the fourth scenario)

would not be able to meet the required CRAR levels.

Liquidity risk

2.43 A stress test on liquidity risk was carried out

using two different scenarios assuming 50 per cent

and 100 per cent increase in cash outflows in the one

to 28 days time bucket. It was further assumed that

there was no change in cash inflows under both the

scenarios. The stress test results indicate that the

SUCBs will be significantly impacted under stress

scenarios (out of 50 banks, 24 banks under scenario

I and 38 banks under scenario II).

Rural co-operatives24

Short-term rural credit co-operatives

State co-operative banks

Balance sheet operations

2.44 There was some moderation in the growth of

the overall balance sheet size of state co-operative

banks (StCBs) during 2012-13 to 10.2 per cent from

14.4 per cent in the previous year. This decline was

primarily on account of deceleration in their borrowings, which accounted for about 30 per cent

of their total liabilities, even as deposits registered a

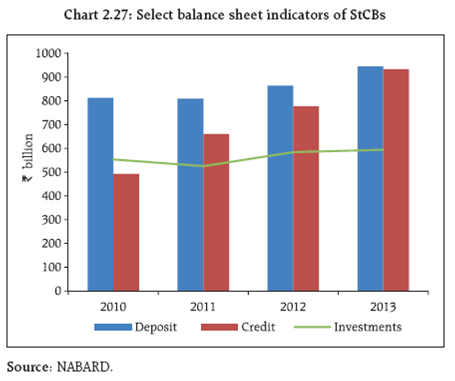

moderate growth (Chart 2.27).

Profitability

2.45 Continuing the trend of the previous year,

net profits of StCBs increased to `11.0 billion during

2012-13 from `6.2 billion in the previous year on the

back of a rise in total income (both interest and noninterest

income) which exceeded the growth in their

total expenditure. The decline in provisions and

contingencies also contributed to the rise in net

profits.

Asset quality

2.46 Although there was a marginal improvement

in the asset quality of StCBs during 2012-13,

the GNPAs ratio still remained high at 6.1 per cent

(Table 2.9).

Table 2.9: Soundness indicators of rural co-operative banks (short-term) |

(amount in ` billion) |

|

StCBs |

DCCBs |

As at end-March |

Percentage Variation |

As at end-March |

Percentage Variation |

2012 |

2013P |

2011-12 |

2012-13P |

2012 |

2013P |

2011-12 |

2012-13P |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

A. Total NPAs (i+ii+iii) |

54 |

56 |

-3.7 |

3.9 |

161 |

181 |

8.8 |

12.0 |

i. Sub-standard |

16 |

21 |

-8.6 |

30.1 |

63 |

79 |

6.4 |

25.7 |

|

(29.2) |

(36.6) |

|

|

(38.9) |

(43.6) |

|

|

ii. Doubtful |

24 |

20 |

-7.8 |

-15.3 |

71 |

76 |

13.9 |

7.1 |

|

(43.4) |

(35.4) |

|

|

(44.2) |

(42.2) |

|

|

iii. Loss |

15 |

16 |

10.4 |

6.3 |

27 |

26 |

2.1 |

-6.5 |

|

(27.4) |

(28.0) |

|

|

(17.0) |

(14.2) |

|

|

B. NPA-to-Loans Ratio (%) |

7.0 |

6.1 |

- |

- |

10.2 |

9.9 |

- |

- |

C. Recovery-to-Demand Ratio (%)

(as on 30 June of previous year) |

95.6 |

94.8 |

- |

- |

79.2 |

80.0 |

- |

- |

P : Provisional

Notes: 1. Figures in parentheses are percentages to total NPAs.

2. Percentage variation could be slightly different because absolute numbers have been rounded off to `billion.

Source: NABARD |

District central co-operative banks

Balance sheet operations

2.47 There was a deceleration in growth of the

overall balance sheet of district central co-operative

banks (DCCBs) in 2012-13 which was evidenced by

decline in asset growth to 13.3 per cent during the

year from 14.5 per cent during 2011-12.

Profitability

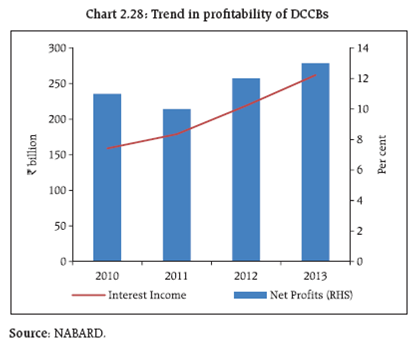

2.48 DCCBs reported decline in growth in net

profits in 2012-13 mainly on account of moderate

increase in both interest as well as non-interest

income (Chart 2.28). This is despite that provisions

and contingencies witnessed a sharp decline during

the year.

Asset quality

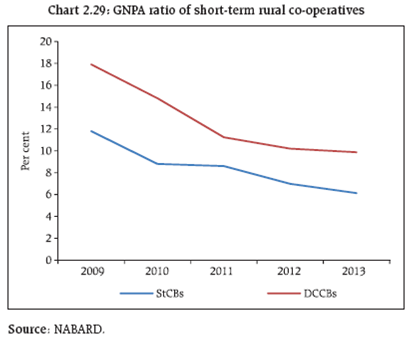

2.49 The reduction in provisions of DCCBs was

primarily on account of an improvement in asset

quality with a decline in the overall GNPA ratio from

10.2 per cent to 9.9 per cent between 2011-12 and

2012-13 (Chart 2.29). Notwithstanding this

improvement, the high GNPA ratio for DCCBs

remained a matter of concern.

Primary agricultural credit societies

Balance sheet operations

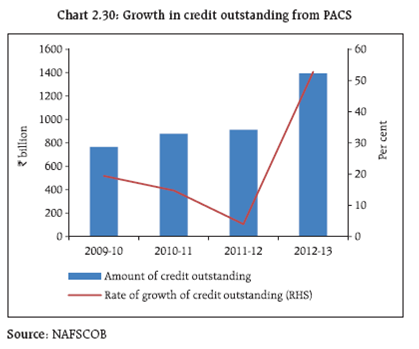

2.50 During 2012-13 an analysis of select indicators

on the balance sheets of primary agricultural credit

societies (PACS) suggests certain positive changes.

Their owned funds increased with lower growth in

borrowings. Loans outstanding during the year also

witnessed higher growth (Chart 2.30).

Profitability

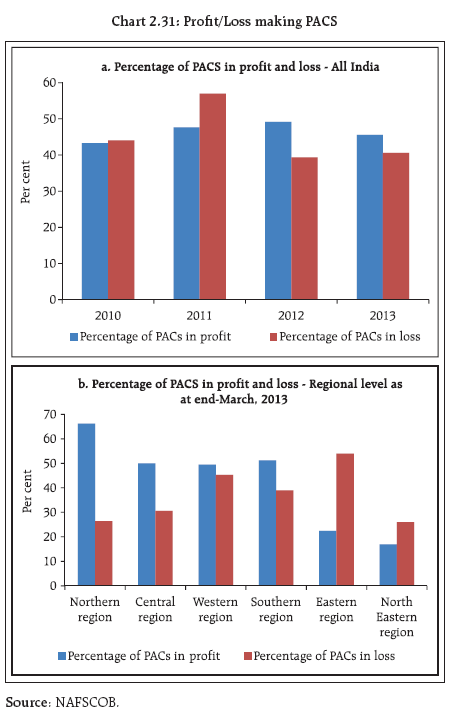

2.51 As of March 2013, about 41 per cent of all the

PACS in the country reported losses, while about 46

per cent were making profits. There was a concentration

of loss making PACS in the eastern region (Chart 2.31).

Long-term rural credit co-operatives

State co-operative agriculture and rural

development banks

Balance sheet operations

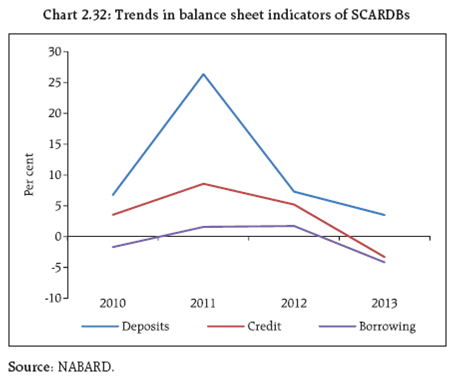

2.52 There was continued deceleration in balance

sheet growth of state co-operative agriculture and

rural development banks (SCARDBs) in 2012-13; this

was contributed to by all major components on the

liabilities and assets sides (Chart 2.32).

Profitability

2.53 Apart from the continued decline in their

asset sizes, SCARDBs also incurred losses to the tune

of `1.0 billion in 2012-13. These losses were primarily

on account of large provisioning towards loan losses.

Asset quality

2.54 There was a decline in the asset quality of

SCARDBs in 2012-13 taking their GNPA ratio to a high

of 36 per cent (Table 2.10).

Table 2.10: Soundness indicators of rural co-operative banks (long-term) |

(in ` billion) |

Item |

SCARDBs |

PCARDBs |

As at end- March |

Percentage Variation |

As at end-March |

Percentage Variation |

2012 |

2013P |

2011-12 |

2012-13P |

2012 |

2013P |

2011-12 |

2012-13P |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

A. Total GNPAs (i+ii+iii) |

64 |

68 |

7.7 |

5.1 |

46 |

46 |

-5.0 |

-0.1 |

i. Sub-standard |

30 |

28 |

1.4 |

-4.4 |

21 |

20 |

-14.5 |

-4.3 |

|

(46.1) |

(41.9) |

|

|

(45.3) |

(43.5) |

|

|

ii. Doubtful |

34 |

38 |

13.8 |

10.2 |

25 |

26 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

|

(53.6) |

(56.2) |

|

|

(53.9) |

(56.1) |

|

|

iii. Loss |

0.2 |

1.2 |

8.3 |

603.0 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

58.1 |

-35.0 |

|

(0.3) |

(1.8) |

|

|

(0.7) |

(0.5) |

|

|

B. GNPA-to-Loans Ratio (%) |

33.1 |

36.0 |

- |

- |

36.7 |

37.1 |

- |

- |

C. Recovery-to-Demand Ratio (%) (as on 30 June of previous year) |

40.2 |

32.3 |

- |

- |

47.3 |

42.7 |

- |

- |

P: Provisional

Note: 1. Figures in parentheses are percentages to total GNPAs.

2. Percentage variation could be slightly different because absolute numbers have been rounded off to `billion.

Source: NABARD. |

Primary co-operative agriculture and rural development banks

Balance sheet operations

2.55 The asset growth of primary co-operative

agriculture and rural development banks (PCARDBs)

further declined to 1.7 per cent in 2012-13 from 5.5

per cent during the previous year. These institutions

also showed weak growth in owned funds (including

capital and reserves) as well as negative growth in

credit outstanding during the year.

Profitability

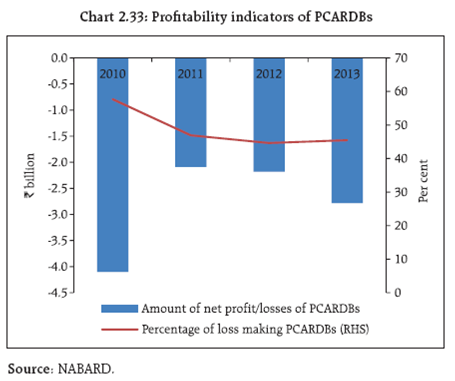

2.56 The number of loss making PCARDBs

marginally increased to 318 during 2012-13

(Chart 2.33). On aggregate basis, PCARDBs reported

losses in 2012-13.

Asset quality

2.57 The asset quality of PCARDBs continued to

be fragile with their GNPA ratio increased to 37 per

cent in 2012-13 (Table 2.10).

Non-banking financial companies

2.58 As of March 2014, there were 12,029 NBFCs

registered with the Reserve Bank, of which 241 were

deposit-accepting (NBFCs-D) and 11,788 were nondeposit

accepting (NBFCs-ND). NBFCs-ND with assets

of `1 billion and above had been classified as

Systemically Important Non-Deposit accepting NBFCs

(NBFCs-ND-SI)25 since April 1, 2007 and prudential

regulations such as capital adequacy requirements

and exposure norms along with reporting requirements

were made applicable to them. From the standpoint

of financial stability, this segment of NBFCs assumes

importance given that it holds linkages with the rest

of the financial system (further discussed in Chapter

III, paras 3.21 to 3.23).

Performance

2.59 During 2013-14, the overall balance sheet of

NBFCs-ND-SI expanded by 9.5 per cent (Table.2.11).

Loans and advances (a major component on the assets

side) increased by 11.2 per cent. Total borrowings,

which constituted more than two-third of their

liabilities, increased by 9.8 per cent.

Table 2.11: Consolidated balance sheet of NBFCs-ND-SI

(As of March) |

(in ` billion) |

Item |

2013 |

2014P |

Percentage

Variation |

1. Share Capital |

647 |

695 |

7.4 |

2. Reserves & Surplus |

2,276 |

2,457 |

8.0 |

3. Total Borrowings |

8,104 |

8,902 |

9.8 |

4. Current Liabilities & Provisions |

574 |

647 |

12.8 |

Total Liabilities/ Assets |

11,601 |

12,701 |

9.5 |

1. Loans & Advances |

7,600 |

8,455 |

11.2 |

2. Hire Purchase Assets |

805 |

896 |

11.3 |

3. Investments |

1,945 |

2,075 |

6.6 |

4. Other Assets |

1,250 |

1,276 |

2.1 |

Memo Items |

1. Capital Market Exposure (CME) |

885 |

1,029 |

16.4 |

2. CME to Total Assets (per cent) |

7.6 |

8.1 |

|

3. Leverage Ratio |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

P: Provisional

Note: 1. Data presented here pertain to 420 entities which account for

more than 95 per cent of the total assets of the NBFCs-ND-SI

sector.

2. Percentage figures are rounded-off.

Source: RBI supervisory returns. |

2.60 The financial performance of NBFCs-ND-SI

improved during 2013-14 as their net profit to total

income increased from 18.3 per cent to 20.2 per cent.

As a result, return on assets rose to 2.3 per cent as of

March 2014 from 2.0 per cent a year ago

(Table 2.12).

Table 2.12: Financial performance of NBFCs-ND-SI sector

(As of March) |

(in ` billion) |

Items |

2013 |

2014 P |

1. Total Income |

1,272 |

1,436 |

2. Total Expenditure |

1,039 |

1,147 |

3. Net Profit |

233 |

290 |

4.Total Assets |

11,601 |

12,701 |

Financial Ratios (per cent) |

(i) Net Profit to Total Income |

18.3 |

20.2 |

(ii) Net Profit to Total Assets |

2.0 |

2.3 |

P: Provisional.

Source: RBI supervisory returns. |

Asset quality

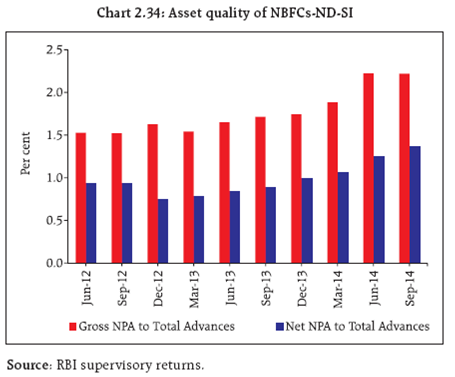

2.61 The asset quality of the NBFCs-ND-SI sector

has been deteriorating since the quarter ended March

2013 (Chart 2.34). The Reserve Bank issued separate

guidelines for both banks and NBFCs with an objective

of mitigating the stress due to their NPAs. NBFCs were

advised to identify incipient stress in their accounts

by creating a sub-asset category viz. ‘Special Mention

Accounts’ (SMA), which was further divided into three

sub-categories (viz., SMA-0, SMA-1 and SMA-2) based

on the extent of principal or interest payment overdue

as also the weakness of their accounts. They were also

directed to report relevant credit information to the

Central Repository of Information on Large Credits

(CRILC).

Capital adequacy

2.62 As per the guidelines, NBFCs-ND-SI

are required to maintain a minimum capital

consisting of Tier-I26 and Tier-II capital, of not less

than 15 per cent of their aggregate risk-weighted

assets. As of March 2014, by and large, the capital

adequacy position of the NBFCs-ND-SI remained

comfortable and was well above prudential norms.

Nevertheless, CRAR of the NBFCs-ND-SI slipped from

the peak of 29.0 per cent as of September 2013 to

27.2 per cent as of March 2014. It subsequently

recovered to 27.8 per cent by the quarter ended

September 2014 (Chart 2.35).

Profitability

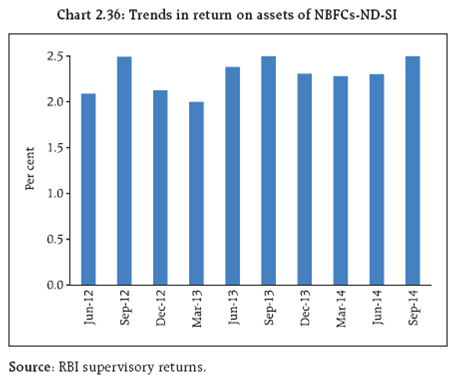

2.63 RoA of NBFCs-ND-SI increased to 2.5 per cent

in September 2014 after remaining at around 2.3 per

cent in previous three quarters (Chart 2.36).

Stress tests: Credit risk

System level

2.64 A stress test on credit risk for NBFC sector27 as

a whole for the period ended September 2014 is carried

out under three scenarios: (i) GNPA increased by 0.5

SD (ii) GNPA increased by 1 SD and (iii) GNPA is

increased by 3 SD. The results suggest that under first

two scenarios, CRAR of the NBFC sector is unaffected

while in the third scenario, it declines to 23.0 per cent

from its level of 23.6 per cent.

Individual NBFCs

2.65 A stress test on credit risk for individual

NBFCs is also conducted for the same period under

the same three scenarios. The results indicate that

under scenarios (i) and (ii) around 1.6 per cent of the

companies will not be able to comply with the

minimum regulatory capital requirements of 15 per

cent, while 4.1 per cent of companies will not be able

to comply with the minimum regulatory CRAR norm

under third scenario.

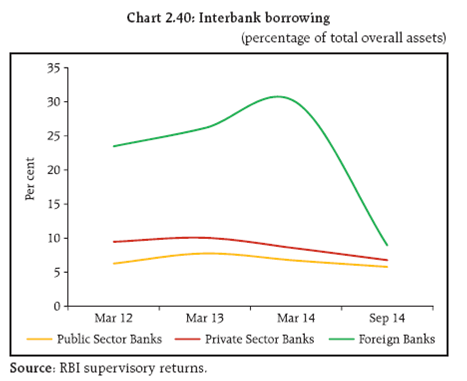

Interconnectedness

Trends in the interbank market

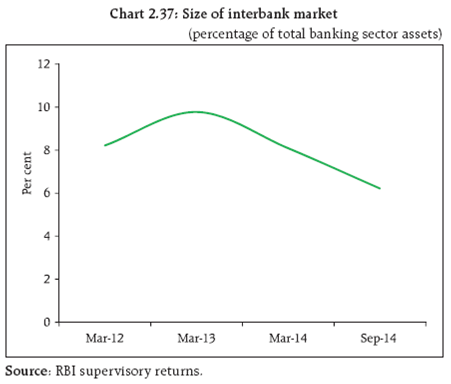

2.66 Banks’ dependence on the interbank market

for liquidity as well as long term uses reveals certain

noteworthy trends. While the size of the market in

absolute terms has hovered around a range of `6 to

8 trillion over the last ten quarters, the market as a

percentage of total banking sector assets has

witnessed a steady decline (Chart 2.37).

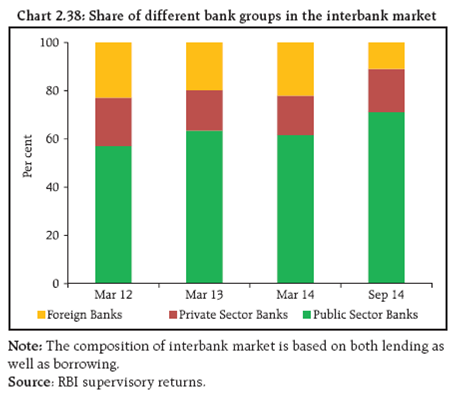

2.67 PSBs continue to be the biggest players in the

market with a share of over 70 per cent as of

September 2014. The share of foreign banks in the

interbank market, however, has declined considerably

since March 2012 (Chart 2.38).

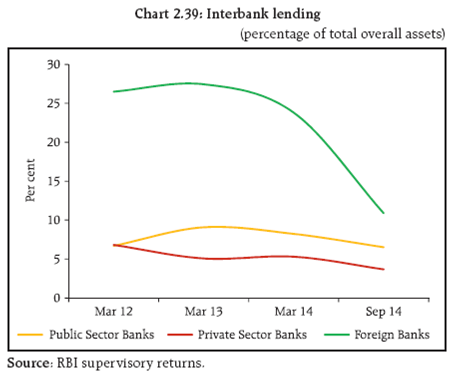

2.68 The ratio of lending and borrowing28 in the

interbank market by each bank group to its respective

total assets is an important indicator of business

models employed by a particular group. Foreign banks,

which had the highest ratios in this respect, have

shown a sharp fall in the recent past (Charts 2.39

and 2.40).

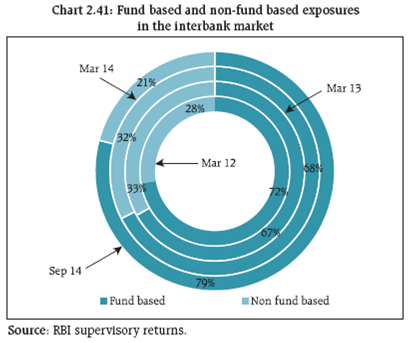

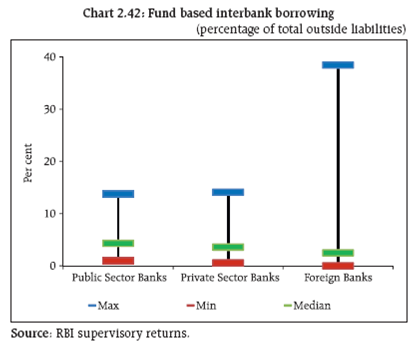

2.69 The interbank market continued to be

predominantly fund based (close to 80 per cent of

the exposures) as of September 2014 (Chart 2.41).

The banking sector as a whole had raised nearly 6

per cent of its total outside liabilities from this market

(Chart 2.42).

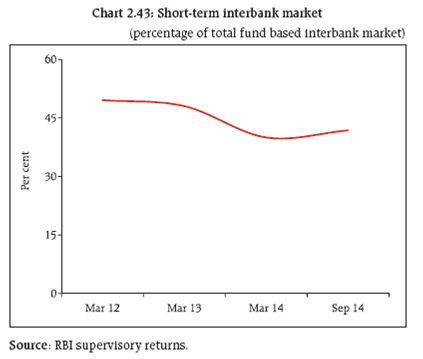

2.70 A substantial portion of fund-based exposures

in the interbank market are short term in nature.

Certificates of deposit (CDs) issued by banks are a

major contributor in this area. The size of the short

term interbank market as a percentage of the total fund-based interbank market stood at over 41 per cent

as of September 2014 (Chart 2.43).

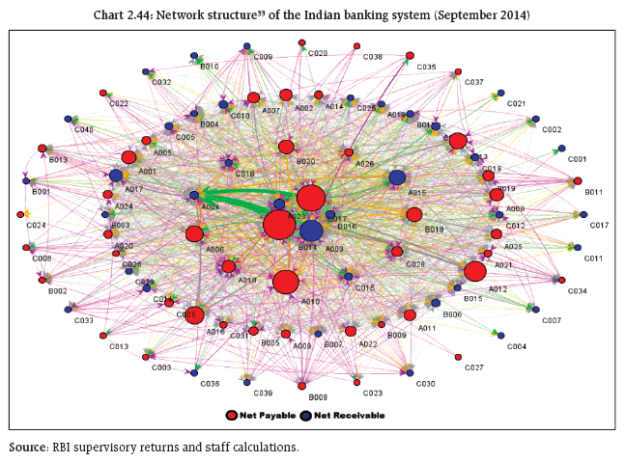

Network structure of the banking system

2.71 The banking system continues to be reasonably

connected with the connectivity ratio,29 which is a

simple estimate of interconnectedness, consistently

remaining over 20 per cent in the last three years. The

network structure30 of the banking system, which is

tiered31 in nature, reveals that the most connected

banks have been the same for the last two years.

Further, the bank which is systemically the most

important32 continues to be the same. PSBs are the

biggest net lenders while private banks are the biggest

net borrowers in the interbank market (Chart 2.44).

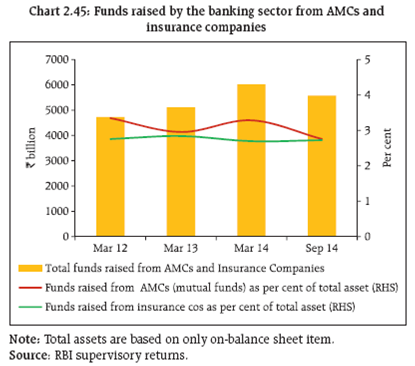

Interconnectedness in the financial system

2.72 A better perspective of the network structure

of the Indian financial system emerges when an

analysis of the interbank market is extended to

include the other two most important sectors: asset

management companies (AMCs) managing mutual

funds and insurance companies.34 The size of this

enlarged market as of September 2014 stood at over

`12 trillion which is roughly double the size of the

interbank market. Both mutual funds and insurance

companies are the biggest providers of funds in this

system, while the PSBs emerge as the largest receiver

of funds. Total funds raised by the banking sector

from mutual funds and insurance companies was to

the tune of `5.5 trillion (Chart 2.45).

2.73 When viewed from a different angle, AMCs’

and insurance companies’ investments in the banking

sector as a percentage of their respective assets under

management (AuM) were also sizeable.35 The interconnectedness that exists between different

sectors in the financial system does expose the system

to contagion risks in the event of stress scenarios.

Irrespective of this, good interconnectedness amongst

financial institutions is a necessary evil (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1: Interconnectedness in the Financial System: How Vital and How Critical

The post-crisis experience of many features in the

financial system which were not given due attention

earlier, led to the calibration of many new regulatory

standards. More notably, in addition to keeping a tab

on individual institutions, the importance of a macro

view of the financial system was acknowledged. Among

the many structures that emerged was ‘Too Connected

to Fail (TCTF)’. The US experience of one institution

going bust leading to the failure of a dozen others

due to common exposures, led the world to come

alive to the phenomenon of ‘interconnectedness’ that

exists between financial institutions. Subsequently,

interconnectedness has been accepted by standard

setting bodies as one of the parameters for identifying

systemically important financial institutions.

Why then are network models being increasingly used

across the world to assess interconnectedness among

financial institutions? The answer lies in the fact that

financial networks are complex and adaptive systems. They are complex because the interconnections involved

among financial institutions are massive and they are

adaptive because while individual institutions in the

system always want to be in an optimal position, they

are not fully informed. Such complex adaptive systems

have the potential to amplify losses manifold during

crisis events. This is exactly what happened during

the Lehman fallout when many institutions shut their

doors and refused liquidity to institutions just because

they were suspected of being ‘infected’.

To begin with, network models assist in understanding

the structure and pattern of connections in a particular

system. If the institutions with high centrality scores

are also heavy net borrowers in the system, then there

might be potential stability issues in the event of any

such institution facing distress. These sort of indications

can provide valuable inputs to a regulator in reassessing

the available redundancies in the system and initiate

counteractive measures.

Contagion analysis

2.74 A contagion analysis36 is conducted to

estimate potential loss to the banking system triggered

by either one or several banks. Though such an

analysis may appear hypothetical, it is a good indicator

about the toxicity of banks. The results further

provide an additional input in identifying systemically

important banks. Three types of contagion analysis

are generally carried out: solvency contagion, liquidity

contagion and joint liquidity-solvency contagion.

Solvency contagion is typical to distress generated by

the failure of a bank which is a net borrower in the

financial system. On the other hand, liquidity

contagion is generated by a net lender bank. In the

actual world, both solvency and liquidity contagion

are likely to emanate simultaneously due to the

obvious dynamics present in a financial system.

2.75 An analysis of the top five connected banks

as trigger banks reveals that the banking system could

potentially lose close to 50 per cent of its total Tier-I

capital under the joint solvency-liquidity condition in the event of a particular bank triggering a contagion

(Table 2.13). It may be noted that Bank E, which does

not cause substantial solvency or liquidity contagion

on a standalone basis, does have a massive impact

under the joint scenario. This is because Bank E is

causing distress to one particular bank that in turn is

magnifying the contagion. This underscores the

importance of monitoring not just the

interconnectedness, but also the counterparties and

magnitude of exposure involved in the connection.

Table 2.13: Contagion triggered by the top-5 connected banks in the system |

Trigger Banks |

Percentage loss of total Tier-I capital of the banking system |

Solvency Contagion |

Liquidity Contagion |

Joint Solvency-Liquidity Contagion |

Bank A |

3.4 |

13.7 |

37.1 |

Bank B |

0.7 |

11.2 |

49.5 |

Bank C |

5.5 |

0.9 |

42.5 |

Bank D |

0.5 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

Bank E |

4.4 |

3.3 |

47.5 |

Source: RBI supervisory returns and staff calculations. |

|