The macroeconomic environment in 2014-15 was marked by a modest pick-up in activity amidst building internal

and external stability, against the backdrop of a tepid and multi-speed global recovery across regions. Going forward,

the economy needs to grapple with significant challenges in the path towards realising its potential and sustaining

the growth process. Importantly, structural constraints to growth and asset quality concerns need to be addressed

sooner than later.

II.1 THE REAL ECONOMY

II.1.1 In January 2015, the Central Statistics

Office (CSO) released a new series on India’s

national accounts. The distinguishing features of

the new series are: (i) updating the base year from

2004-05 to 2011-12; (ii) improved coverage of

corporate activity by (a) using the MCA 21

database1 of the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, (b)

employing value-based indicators such as sales

tax collections in conjunction with volume-based

indicators such as industrial production, and (c) use

of results from the latest surveys, including on

activity in the unorganised sector; and (iii)

methodological changes such as shifting from the ‘establishment’ to the ‘enterprise’ approach for

estimating value added in mining and manufacturing.

In line with international practices, GDP at market

prices will henceforth be the headline measure for

output. Gross value added (GVA) at basic prices

will measure activity from the supply side instead

of GDP at factor cost. In terms of the new series,

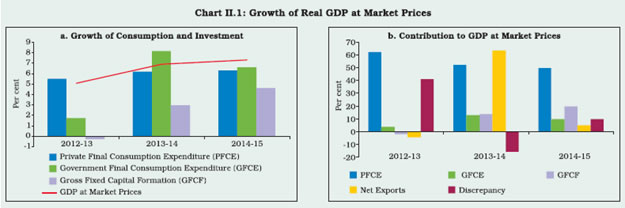

real activity (at market prices) picked up in 2014-15,

rising by 7.3 per cent on top of a growth of 6.9 per

cent in 2013-14 (Chart II.1). The firming up of

growth during 2014-15 was driven mainly by private

consumption and supported by fixed investment,

even as government consumption and net exports

slackened considerably.

II.1.2 From the supply side, the quickening of

activity in 2014-15 was largely led by industry and

services (Chart II.2). Within industry, higher growth

was observed in manufacturing and electricity

generation. The share of manufacturing was

augmented by trading activity of constituent entities

which formed part of services in the old series. In

the services sector, ‘financial, real estate, and

professional services’ as well as construction were

the primary drivers. On the other hand, the

agriculture sector lost momentum, adversely

impacted by the deficient southwest monsoon

(SWM) which affected kharif sowing and by

unseasonal rains and hailstorms at the time of rabi

harvesting.

II.1.3 Thus, in terms of the new series, India

emerged among the fastest growing economies in

the world, notwithstanding the still sluggish global

economy which dragged down the contribution of

net exports to growth in 2014-15.

Saving and Investment

II.1.4 In 2013-14, the gross domestic saving rate

declined for the second consecutive year to 30 per

cent of gross national disposable income (GNDI)

(Table II.1) This largely reflected the reduction in

the saving rate of households on account of a

decline in physical assets as well as in valuables.

On the other hand, household financial saving

gained from returns turning attractive with the moderation in inflation as well as the pick-up in

economic activity. For 2014-15, CSO has not yet

released its estimates of gross saving. However,

in terms of the Reserve Bank’s preliminary

estimates, household financial saving is placed at

7.5 per cent of GNDI in 2014-15, up from 7.3

per cent in 2013-14.

| Table II.1: Gross Saving (As a ratio of GNDI) |

| (Per cent) |

| Item |

2011-12 |

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 1 |

Gross Savings |

33.0 |

31.1 |

30.0 |

| |

1.1 Non-financial Corporations |

9.7 |

9.6 |

10.3 |

| |

1.1.1 Public non-financial corporations |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

| |

1.1.2 Private non-financial corporations |

8.3 |

8.4 |

9.3 |

| |

1.2 Financial Corporations |

2.9 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

| |

1.2.1 Public financial corporations |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

| |

1.2.2 Private financial corporations |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

| |

1.3 General Government |

-1.8 |

-1.3 |

-1.0 |

| |

1.4 Household sector |

22.2 |

19.7 |

17.8 |

| |

1.4.1 Net financial saving |

7.1 |

6.8* |

7.1* |

| |

1.4.2 Saving in physical assets |

14.8 |

12.6 |

10.4 |

| |

1.4.3 Saving in the form of valuables |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

Note: Net financial saving of the household sector is obtained as the difference between change in financial assets and change in financial liabilities.

Source: Central Statistics Office.

*: As per Reserve Bank’s latest estimates, household financial saving for 2012-13 and 2013-14 are 7.0 per cent and 7.3 per cent, respectively, of GNDI. |

II.1.5 As regards the saving rate of the private

corporate sector, non-financial corporations posted

a near-steady improvement since 2011-12, i.e.,

since the new series is available, but it appears that

this increase may not have sustained in 2014-15.

Private financial corporations, on the other hand,

underwent some erosion in saving rates in 2013-14,

partly reflecting the slowdown in the growth of

operating profits of private sector banks. Available

indicators suggest that this has been recouped in

2014-15.

II.1.6 The ongoing reduction in ‘dissaving’ of the

general government boosted the gross national

saving rate in 2013-14. With the perseverance of

fiscal consolidation, especially by the centre, the

decline in the dissaving of the government sector

has likely continued into 2014-15. There was,

however, a decline in the saving rate of the public

financial (including public sector banks) and nonfinancial corporations in 2013-14. In case of public

sector banks, there was a decline in profit after tax

during 2014-15.

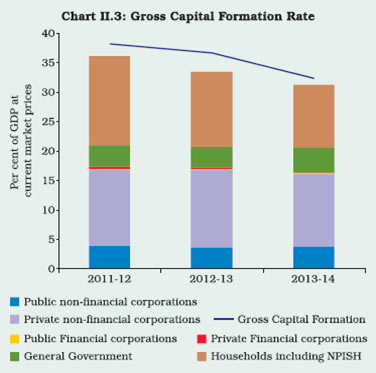

II.1.7 The investment rate (gross capital

formation as a proportion to GDP at current market

prices) declined in 2012-13 and 2013-14, largely

reflecting the slackening in the non-financial

corporations’ investment rate on account of weak

domestic and external demand and other structural

factors such as delay in land acquisition and

environment clearances, weak business confidence

and policy uncertainties. The household sector’s

investment rate also declined in 2012-13 and

2013-14. The improvement in general government

investment in 2013-14 did, however, provide some

offset (Chart II.3).

II.1.8 Viewed in conjunction with other indicators

of investment activity such as stalled projects, capital goods imports/production and capex

spending, the decline in the private investment

intention appears to have become more pronounced

in 2014-15 relative to the preceding year. As per

the Reserve Bank’s data on new projects which

were sanctioned financial assistance by banks/

financial institutions (FIs) or funded through external

commercial borrowings (ECBs)/foreign currency

convertible bonds (FCCBs)/domestic capital market

issuance, investment intentions for such projects

aggregated to ₹1,459 billion during 2014-15 as

against ₹2,081 billion in the previous year. A

turnaround in the investment demand cycle,

therefore, assumes critical importance to steer the

economy on to a sustainable high growth trajectory.

The recent experience suggests that a strong stepup

in public investment may be required to dispel

the inertia constraining private investment and to

crowd it in, given the robust business sentiment.

Key to this effort will be putting stranded investments

in stalled projects back to work while ensuring the

availability of key inputs such as power, land

(especially for roads) and skilled labour. Steadfast

implementation of structural reforms like the goods

and services tax (GST) is also required to

reinvigorate productivity and competitiveness.

Agriculture

II.1.9 The vagaries of the monsoon were in full

play during 2014-15. The likelihood of El Nino

emerging, was initially placed high, but it eventually

did not materialise. Nevertheless, delay, deficiency,

and unevenness in rainfall during the SWM season

led to a decline in the production of most kharif

crops. The deficient SWM did not replenish soil

moisture adequately and, in addition, the northeast

monsoon (NEM) also turned deficient. With the

production of most rabi crops estimated lower, the

initial hope that a good rabi harvest could make up

for the kharif losses was belied. At the end of the

seasons, the SWM turned 12 per cent below the

long period average (LPA) and the NEM 33 per cent

below the LPA. In addition to under-replenishment

of reservoirs and intermittent dry halts, a bigger

blow to rabi crops, mainly to wheat, came in the

form of unseasonal rainfall and hailstorms during

late February and early March 2015. As per the

fourth advance estimates of the Ministry of

Agriculture released on August 17, 2015, the total

foodgrains production declined by 4.6 per cent.

Similarly, the production of oilseeds and cotton

declined by 18.5 per cent and 1.2 per cent

respectively, though that of sugarcane increased by 2.0 per cent. The impact of a decline in the

volume of foodgrains production to 252.7 million

tonnes from 265.0 million tonnes a year ago may,

however, be mitigated by the availability of food

stock buffers of 55.6 million tonnes (end-July 2015),

which is much higher than the buffer norm which

varies between 21.0-41.1 million tonnes.

II.1.10 For the 2015 SWM season, the India

Meteorological Department (IMD) has forecast

precipitation at 88 per cent of the LPA in June 2015,

and retained the same forecast in August 2015 with

a higher likelihood of El Nino effect intensifying

during the season2. Though delayed in arrival, the

rainfall was in excess in June barring the last week

when a dry spell set in and continued till mid-July,

limiting the season’s precipitation to 9 per cent

below LPA so far (August 19, 2015). Better rainfall

in June augmented sowing under most kharif crops

vis-à-vis last year. In view of these developments,

the prospects of kharif harvest 2015 could be

expected better notwithstanding the persisting risks

to supply shortfalls and likely inflation pressures

given the unpredictability of SWM during the

remaining part of the season, alongside the need

for reappraisal of the degree of weather proofing of

Indian agriculture in the context of monsoon

vagaries (Box II.1).

Box II.1

How Monsoon Proof is Indian Agriculture?

Historically, agricultural failures in India have often been

associated with deficient south west monsoons (SWM). The

SWM which constitutes 75-80 per cent of total rainfall received

in India, coincides with kharif sowing and is vital for

replenishment of ground water, soil moisture and reservoirs

and thus crucial for a good rabi harvest as well. Visual

observation of trend growth rates of agriculture seems to

suggest resilience at least in some bad monsoon years

(Chart 1).

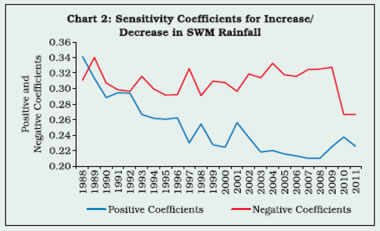

Empirical analysis of positive and negative SWM shocks

suggests that during 1988-2012, the impact of variations in

SWM is statistically significant for agricultural output, but it is much less than that of variations in net sown area (Chart 2).

The absence of multicollinearity between rainfall and sown

area is validated by variance inflation factor (VIF).

Clearly, Indian agriculture is yet to become fully weather

proof and public policy interventions to insulate crop

production from monsoon shocks is an imperative. Saturation

of land use and exhaustion of economies of scale can be

halted by multi-pronged strategies covering, inter alia, credit,

capital and machinery, technology, research and

development, use of improved and hybrid seeds, irrigation

and water management, and land reclamation including in

arid and semi-arid areas while more vigorously pursuing the scheme of extending the green revolution in the east. A

diversified approach to agricultural development with

emphasis on livestock, fishery, forestry and logging will also

buffer agricultural output from SWM variations, provided it

is pursued in the overall context of food and nutritional

security.

Contingency plans put in place during 2009-10 in the face of

a 22 per cent shortfall in SWM warrant careful consideration

for replication. The provision of quality and short duration

seeds, agricultural inputs, an active rabi campaign and an

action plan for the next cropping season, media telecasting

and awareness campaigns, enhanced availability of funds

under centrally sponsored programmes, and additional diesel

subsidy for irrigation served well, bringing home the point that

the impact of adverse monsoon shocks can be ameliorated

by pro-active policy measures.

References:

Aggarwal P.K. et al. (2009), ‘Vulnerability of Indian Agriculture

to Climate Change: Current State of Knowledge’ available at

http://www.moef.nic.in

RBI Bulletin (2015), ‘Monsoon and Indian Agriculture –

Conjoined or Decoupled?’, May.

Industry

II.1.11 Industrial production turned around from

the contraction recorded in 2013-14 and posted a

growth of 2.8 per cent during 2014-15. The

production of consumer durables continued to

shrink as in the previous year, especially telephone

instruments, including mobile phones which was

due to the one-off closure of Nokia’s manufacturing

unit in Chennai in November 2014. Excluding this

category, industrial production would have risen by

5.3 per cent during 2014-15 (Chart II.4).

II.1.12 Higher production of basic metals, electricity

and capital goods drove up the index of industrial

production (IIP) growth during 2014-15. In terms of

the use-based classification, the production of basic

and capital goods accelerated, while that of

intermediate goods decelerated and the output of

consumer goods contracted (Table II.2).

| Table II.2: Index of Industrial Production |

| (Per cent) |

| Industry Group |

Weight in IIP |

Growth Rate |

| 2011-12 |

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

April-June 2015-16P |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| Overall IIP |

100.0 |

2.9 |

1.1 |

-0.1 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

| Mining |

14.2 |

-2.0 |

-2.3 |

-0.6 |

1.5 |

0.7 |

| Manufacturing |

75.5 |

3.0 |

1.3 |

-0.8 |

2.3 |

3.6 |

| Electricity |

10.3 |

8.2 |

4.0 |

6.1 |

8.4 |

2.3 |

| Use-Based |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Basic Goods |

45.7 |

5.5 |

2.5 |

2.1 |

7.0 |

4.7 |

| Capital Goods |

8.8 |

-4.0 |

-6.0 |

-3.6 |

6.4 |

1.5 |

| Intermediate Goods |

15.7 |

-0.6 |

1.6 |

3.1 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

| Consumer Goods |

29.8 |

4.4 |

2.4 |

-2.8 |

-3.4 |

2.4 |

| Consumer Durables |

8.5 |

2.6 |

2.0 |

-12.2 |

-12.6 |

3.7 |

| Consumer Non-durables |

21.3 |

5.9 |

2.8 |

4.8 |

2.8 |

1.6 |

| Source: Central Statistics Office.

P: Provisional |

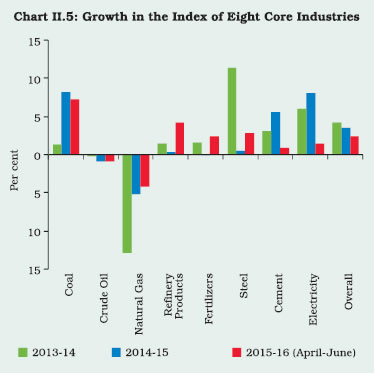

II.1.13 Mining activity recovered during 2014-15

from a three-year slump, buoyed by a sharp increase in the production of coal (Chart II.5). Among other

items within the mining sector, the production of

crude oil declined on account of ageing oil fields and

delay in the execution of new oil field projects. Also,

contraction in the production of natural gas from the

KG-D6 block affected natural gas production during

2014-15 as in the previous three years. Electricity

generation registered its highest growth in the last

two decades during 2014-15, facilitated by improved

coal supply and higher capacity addition of 22,566

MW (as against a target of 17,830 MW), which is

the highest ever achieved in a single year. Capacity

addition, coupled with higher generation and

improved transmission capacity resulted in a

considerable reduction in power shortage from a

level of 7 to 11 per cent during the last two decades

to a record low of only 3.6 per cent during 2014-15.

The plant load factor (PLF) in the thermal power

sector was largely sustained in 2014-15. However,

there has been some slippage in the PLF in the first

quarter of 2015-16.

II.1.14 Weakness in consumer spending, sluggish

investment activity and poor external demand operated as drags on manufacturing activity during

2014-15. Within the manufacturing sector, exportoriented

industries like textiles, wearing apparels

and refined petroleum products decelerated. On

the other hand, capital goods industries like

machinery and equipment and electrical machinery registered improved growth. Revival in the

production of capital goods after three years of

contraction signals improved prospects for

investment demand going forward. During April-

June 2015, however, the growth in IIP decelerated

mainly on account of a sluggish performance in

capital goods, electricity and food products.

Services

II.1.15 The services sector is estimated to have

grown by 9.4 per cent during 2014-15 mainly driven

by ‘financial, real estate and professional services’

and construction sector. As for 2015-16, available

data on lead indicators of services sector including

commercial/passenger vehicles sales, air passenger

traffic, port and international air cargo, show an

improvement over the corresponding period last

year. However, railway freight traffic, domestic air

cargo, tourist arrivals, cement production and steel

consumption - which provide lead indications of

construction activity- show moderation. During

2014-15, purchasing managers index (PMI) for

services remained in an expansionary mode since

May 2014, though the rate of expansion was at a

slower pace in ensuing months. However, PMI

services contracted in May-June 2015 on account

of a decline in both output and new orders though

it expanded marginally in July 2015. Also, given the

drag emanating from fiscal consolidation by central

and state governments on total spending, ‘public

administration, defence and other services’ may not

serve as a durable growth driver, going forward.

Employment Generation

II.1.16 Quarterly employment surveys conducted

by the Labour Bureau for select export-oriented

sectors reveal that the rate of employment

generation in these sectors picked up in 2013 and

2014, after a significant decline in 2012. However, the pace of employment generation is yet to recover

to its pre-2010 level. Information technologybusiness

process outsourcing (IT-BPO) and textiles

continue to be the key export oriented sectors

generating large employment from 2009 to 2014.

Infrastructure

II.1.17 The growth of production in core industries

(coal, crude oil, natural gas, refinery products,

fertilisers, steel, cement and electricity) moderated

during 2014-15 (Chart II.5) and remained sluggish

during April-June 2015. Structural constraints have

resulted in a persistent decline in the production of

natural gas, crude oil and fertilisers. The growth of

the steel industry was affected by the fall in global

prices of steel and the resultant increase in steel

imports. On the other hand, the coal sector’s

impressive growth performance during 2014-15

benefitted from several efficiency enhancing

measures taken by the government for Coal India

Limited (CIL), like use of mass production

technologies, rationalisation of linkages from coal

sources to end-users, coordinated efforts with

railways for speedy evacuation of coal and shifting

to underground mines.

II.1.18 As on mid-August 2015, the government’s

Project Monitoring Group (PMG) has received

proposals for 675 projects (₹10 billion and above

or any other critical projects in sectors such as

infrastructure, manufacturing and power) with an

estimated project cost of ₹28.8 trillion for its

consideration. Out of these, 291 projects worth ₹9.9

trillion were cleared by the PMG with the majority

of projects pertaining to the power sector, followed

by coal, road and petroleum sectors. However, the

impact of government initiatives is yet to be felt in

terms of the revival of central sector infrastructure

projects (₹1.5 billion and above) monitored by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation

(MoSPI) (Table II.3).

|

| Table II.3: Status of Projects |

| Central Sector Infrastructure Projects |

| Period |

Total No. of Projects |

No. of Delayed Projects |

Value of Delayed Projects (₹ billion) |

No. of projects without DOC |

Value of projects without DOC (₹ billion) |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| May-15 |

766 |

237 |

4,826 |

371 |

2,470 |

| Mar-15 |

751 |

328 |

5,752 |

264 |

1,531 |

| Dec-14 |

738 |

315 |

4,961 |

266 |

1,475 |

| Sep-14 |

750 |

312 |

5,504 |

302 |

1,730 |

| Jun-14 |

729 |

290 |

4,975 |

300 |

1,805 |

Source: Infrastructure and Project Monitoring Division, MoSPI, Government of India (GoI).

DOC: Date of Commissioning. |

II.1.19 While investment through the public-private

partnership (PPP) mode was the highest in India

during 2008 to 2012 as per the World Bank’s

database3, thereafter the private participation in

prime infrastructure projects in roads and ports

decreased sharply. The focus of the government

on construction of highways through the publicly

funded engineering, procurement and construction

(EPC) mode is reflected in a marginal improvement

in road construction activity in 2014-15 vis-à-vis

2013-14 (Chart II.6).

II.1.20 Spectrum auctions in March 2015 elicited

vibrant bidding for all the four bands (1800 MHz,

900 MHz, 2100 MHz, and 800 MHz). This is the first

time that spectrum has been offered simultaneously

in all the four bands (Table II.4).

| Table II.4: Spectrum Auction |

Year |

Revenue Realisation (₹ billion) |

1 |

2 |

2010 |

1062.62 |

2012 |

94.07 |

2013 |

36.39 |

2014 |

611.61 |

2015 |

1098.75 |

| Source: Ministry of Information & Communication Technology, GoI. |

II.1.21 The government initiated a number of

structural reforms in the recent period to boost the

infrastructure sector: the passing of the Coal Mines

(Special Provisions) Act, 2015; auctioning of coal

mines; hike in tariffs on iron and steel; adoption of

the plug-and-play mode of project execution for

mega power projects; allowing foreign direct

investment up to 100 per cent in railway infrastructure; the proposed National Investment and

Infrastructure Fund; tax free infrastructure bonds

for projects in the rail, road and irrigation sectors

and increased plan outlays for roads and railways.

II.1.22 In order to give a direct thrust to

infrastructure investment, the government has

stepped in to boost public spending in infrastructure

by ₹700 billion in 2015-16. These efforts are also

expected to crowd in private participation. Going

forward, the government’s decision to award

new projects only after obtaining the requisite

clearances and linkages could catalyse the pace

of infrastructure project completion.

II.2 PRICE SITUATION

II.2.1 The year 2014-15 marked a turning point

in the evolution of price-cost dynamics in India. In

January 2014, the stance of monetary policy was

anchored to a path of disinflation that would take

inflation (measured in terms of y-o-y changes in

the all India consumer price index (combined) or

CPI-C, base 2010 =100) down from 8.6 per cent

to below 8 per cent by January 2015 and to below

6 per cent by January 2016. This stance was

backed by policy rate increases of 25 basis points

each in September 2013, October 2013 and

January 2014. Although unseasonal food price

spikes owing to weather-related transportation

disruptions in north India kept inflation stubbornly

high till July 2014, steadfast perseverance with the

anti-inflationary monetary policy allowed rate

increases in the second half of 2013-14 to feed

through into the economy. Aided by a range of

supply management strategies and a dramatic

plunge in international commodity prices4 by 28

per cent between September 2014 and February

2015, inflation persistence (near double digit CPI

inflation for six consecutive years) was finally

broken and headline inflation started easing from

August 2014. The abatement in food price

pressures contributed 76 per cent to the decline in

inflation between July and November 2014. By April

2015, it had declined to 4.9 per cent measured by

the new CPI series (base 2012=100), thus

confirming that disinflation was getting entrenched.

Notwithstanding an uptick in June 2015 to 5.4 per

cent, largely reflecting fuel price adjustments and

short-term food price pressures, inflation moderated

significantly to 3.8 per cent in July 2015. Importantly,

inflation excluding food and fuel almost halved from

8.3 per cent in May 2014 to 4.2 per cent in March 2015, providing abiding momentum to the

disinflation process. However, this moved

significantly up to 5.0 per cent in June 2015 before

falling to 4.5 per cent in July 2015. By December

2014, households’ inflation expectations (both

three months ahead and one-year ahead), which

had been ruling in double digits persistently since

September 2009, eased to single digit.

II.2.2 Average inflation at 5.9 per cent during

2014-15 turned out to be significantly lower than

9.5 per cent a year ago (Chart II.7). Intra-year

movements in inflation during 2014-15, however,

exhibited three distinct phases – first, weatherrelated

vegetable price pressures till August;

second, the subsequent fall in food prices and

pass-through of declining global commodity prices

into food, fuel and services prices, resulting in a

major shift in the inflation trajectory that took

inflation down to an intra-year low of 3.3 per cent

in November 2014; and finally the reversal of

favourable base effect, which pushed inflation up to 5.3 per cent in March 2015. Significantly, even

as inflation moved up during December 2014 -

February 2015, the month-on-month increase in

prices remained moderate or negative, attesting

to the sustained abatement of inflation risks.

Drivers of CPI Inflation

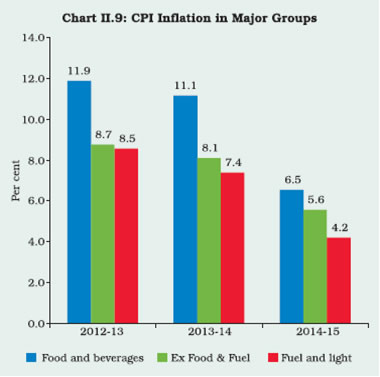

II.2.3 All the three major constituent groups of

CPI - food, fuel and categories excluding food and

fuel - contributed to a decline in headline inflation,

reflecting improvement in supply conditions and

the ebbing of inflation momentum (Chart II.8), with

the largest impact emanating from the food

component. Fuel group’s contribution to inflation

remained marginal, reflective of its relatively lower

weight and declining frequency of changes in

administered prices of non-transport fuel items.

The fall in inflation, excluding food and fuel, was

facilitated by the anti-inflationary monetary policy

stance as inflation in most of its sub-components

edged down.

Food Inflation

II.2.4 The wedge between inflation in food and

non-food groups narrowed considerably during

2014-15 (Chart II.9). Two major groups - cereals

and vegetables - together accounted for almost

80 per cent of the decline in average food price

inflation during the year. Cereals’ inflation declined

partly on account of the lower order of revision in

minimum support prices (MSPs) in 2014-15 (Table

II.5) and active supply management under the public distribution system (PDS), including the

open market sale of wheat. Vegetable prices

shrugged off bouts of weather-related volatility in

H1 of 2014-15 and declined relatively faster in H2

of 2014-15 with policy actions taken to discourage

stockpiling, and bringing vegetables under the

Essential Commodities Act (ECA). Sugar prices

moderated in tandem with global prices, but

protein-rich items (eggs, fish, meat, milk and

pulses) exhibited downward rigidity in inflation,

reflecting structural mismatches between demand

and supply.

| Table II.5: Minimum Support Prices of Food

Grains (₹ per quintal) |

| Commodity |

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

2015-16 |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Paddy (Common) |

1,250 |

1,310 |

1,360 |

1,410 |

| Wheat |

1,350 |

1,400 |

1,450 |

- |

| Gram |

3,000 |

3,100 |

3,175 |

- |

| Arhar (Tur) |

3,850 |

4,300 |

4,350 |

4,425 |

| Moong |

4,400 |

4,500 |

4,600 |

4,650 |

| Urad |

4,300 |

4,300 |

4,350 |

4,425 |

| Source: DAC, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. |

II.2.5 A number of policy initiatives were taken

to improve both supply chain and post-harvest

crop management. These included issuing

advisories to states to enable free movement of

fruits and vegetables by delisting them from the

Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee

(APMC) Act; bringing onions and potatoes under

the purview of ECA, thereby allowing state

governments to impose stock limits so as to deal

with cartelisation and hoarding and making

violation of stock limits a non-bailable offence.

Imposing a minimum export price (MEP) of US$

450 per metric tonne (MT) for potatoes with effect

from June 26, 2014 and US$ 300 per MT for onions

with effect from August 21, 2014 also helped in

maintaining domestic supplies of these perishable

items.

Fuel Group Inflation

II.2.6 From August 2014, crude oil prices fell but

the full pass-through of this decline was impeded

by lingering under-recoveries of the oil marketing

companies (OMCs) (Table II.6). Further, the

government increased the excise duty on petrol

and diesel cumulatively by ₹7.75 per litre for petrol and ₹6.50 per litre for diesel during November

2014 - January 2015, which partially offset the

overall fall in prices. In case of coal, Indian prices

have historically remained substantially lower than

the global prices. Therefore, the decline in global

coal prices during 2014-15 resulted in bridging the

gap between global and domestic prices rather

than a fall in domestic prices. Since the CPI fuel

group includes a number of items, such as

electricity and kerosene whose prices are

administered, prices in this category remained

sticky (Chart II.10).

| Table II.6: Under-recoveries of

Oil Marketing Companies |

| (₹ billion) |

| Product |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

| Diesel |

628 |

109 |

| PDS Kerosene |

306 |

248 |

| Domestic LPG |

465 |

366 |

| Total |

1,399 |

723 |

| Source: PPAC, Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas. |

Inflation Excluding Food and Fuel

II.2.7 Prices in respect of the transport and

communication sub-group declined in tandem with

softening of global crude oil prices. By the end of

the year, the transport and communication

category contributed negatively to inflation (Chart

II.11). Also, housing inflation showed a much more

significant moderation under the new series (base

2012=100) partly on account of methodological

improvements, which included doubling the

sample size for collection of rentals data from

6,684 rented dwellings in the old series to 13,368

in the revised series. Inflation in services

components, such as health, education and

household requisites declined, reflecting a

slowdown in wage growth.

Rural Wage Growth Moderated

II.2.8 Input cost pressures from fuel, farm inputs

and rural wages ebbed significantly during 2014-

15. After the high and unprecedented rise in rural

wages during 2007-08 to 2012-13, the recent

slowdown in wage growth has evoked academic and policy interest. Average wage growth, as per

the new wage series, for November 2014 to May

2015, remained at 3.9 per cent for agricultural and

5.7 per cent for non-agricultural occupations,

respectively. This was substantially lower than the

annual average rate of 16 per cent for agricultural

occupations and 14 per cent for non-agricultural

occupations during the six-year period from 2007

to 2013. However, the role of productivity will have

to be examined carefully while assessing the

durability of the impact of the changes in wage

growth on inflation (Box II.2).

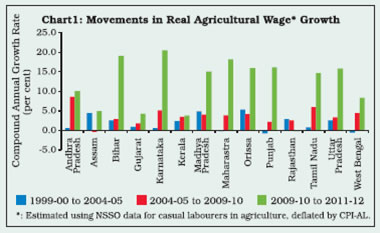

Box II.2

Wage Growth and Rural Inflation – Are They Related?

An increase in rural wages can influence prices, both by

increasing demand and pushing up the cost of production.

On the other hand, wage growth in itself could respond to

high price increases, particularly food price increases. The

wage-inflation nexus also works through productivity - as

labour productivity increases, wages rise. An increase in

labour productivity will reduce unit labour cost, which is the

average cost of labour per unit of output (usually calculated

as the ratio of total labour costs to real output) and therefore,

it will be possible to pay a higher wage without an increase

in final output price. On the other hand, if wage increases

are unaccompanied by productivity increases, rise in unit

labour costs will lead to further increase in output prices and

hence inflation. This dynamics is more complex in a regional

perspective, where there is large heterogeneity in product

and labour markets.

A comparison between agricultural labour productivity and

agricultural wages at the all-India level as well as for major

states is insightful. Real wage growth, i.e., growth in

agricultural wages adjusted for CPI - agricultural labourers

(AL) inflation, remained moderate during 1999-00 to 2009-

10. Subsequently, it went up sharply during 2009-10 to

2011-12 (Chart 1). This trend was broad-based and

observed in major agricultural states like Bihar, Maharashtra,

Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh.

Agricultural labour productivity declined in some states

over the period from 1999-2000 to 2004-05, but went up

subsequently during the period 2009-10 to 2011-12 at the

all-India level as well as for major states (Chart 2). The

productivity improvement was partly contributed by a shift

in labour force from agricultural to non-agricultural

occupations, which led to a decline in the total number of

persons engaged in agriculture in 2011-12 vis-à-vis 2004-

05. Thus, the sharp increase in real wages in recent years

was partly offset by a rise in productivity. The impact of

rural wage increases on rural food prices was not as large

due to commensurate rise in productivity (Goyal and Baikar

2014). Post-2013, real wage growth declined in India

barring a few states like Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh,

Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. The fall in real wage growth is

mainly contributed by a fall in nominal wage growth.

References:

Dholakia, R.H., M. B. Pandya and P. Pateriya (2014), ‘Urban

– Rural Income Differential in Major States: Contribution of

Structural Factors’, WP No. 7, Indian Institute of Management,

Ahmedabad.

Goyal, A. and A.K. Baikar (2014), ‘Psychology, Cyclicality

or Social Programs: Rural Wage and Inflation Dynamics in

India’, WP, IGIDR, Mumbai.

Wholesale Price Inflation

II.2.9 Inflation measured by the wholesale price

index (WPI) declined significantly during 2014-15.

Since November 2014, wholesale prices have

moved into contraction [(-) 4.1 per cent in July

2015, y-o-y] (Chart II.12). Prices of non-food

manufactured products also contracted in July

2015 [(-) 1.4 per cent, y-o-y], indicating the extent

of slack in the economy as well as falling cost

pressures.

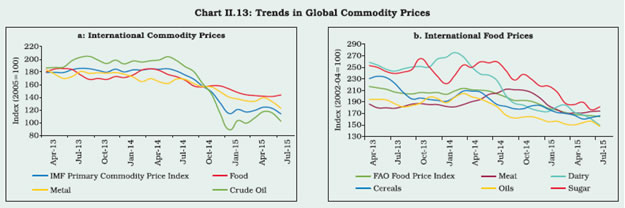

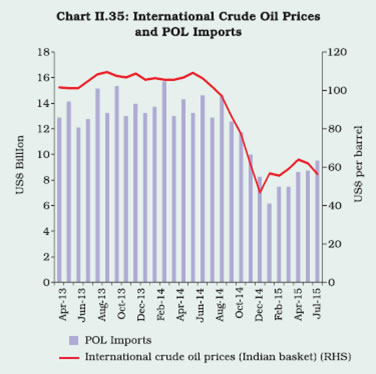

Global Commodity Prices and Supply Conditions

II.2.10 Global commodity prices declined sharply

amidst improved supply, large spare capacity and

weak demand conditions in 2014-15 (Chart II.13).

During the initial part of the year, crude oil prices

hardened on account of supply outages in Libya,

Nigeria and Syria. From August 2014, global

crude oil prices fell substantially, driven by

abundant supplies of North American shale oil

and the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting

Countries’ (OPEC) decision not to cut production

at its November 2014 meeting. Global crude oil

prices reached a trough of US$ 47 per barrel (Indian basket), marking a decline of 57 per cent

during June 2014 to January 2015. Though the

slow pace of global economic recovery has kept demand prospects weak, the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated that lower

demand could account for only 20 to 35 per cent of the price decline between June and December

2014.

II.2.11 Since January 2015, several factors, such

as falling oil rigs in the US, decline in stockpiles

and elevated geo-political tensions in the Middle

East rekindled upside risks to oil prices. Indian

basket prices firmed up to US$ 63.8 per barrel in

May 2015 but declined subsequently to US$ 49

per barrel by mid-August 2015 as supply prospects

improved with the clinching of the nuclear deal by Iran with the major world powers. Metal prices

edged down in 2014 aided by surplus supplies

and slowing demand conditions in emerging

economies, particularly in China.

II.2.12 Global food prices declined by 3.8 per cent

in 2014 as large accumulated stocks continued to

pull down international prices of commodities, such

as cereals, oils and sugar. The Food and Agriculture

Organisation (FAO), in its update of July 2015,

forecast that the world cereals production might

decline by 1.1 per cent in 2015 while exceptionally

high stocks were likely to compensate for the

production shortfall. During 2015 so far, prices have

continued to move downwards for almost all food

items, with large supplies and slow trading activity

as buyers are expecting a further fall in prices in

the coming months.

Revision in the CPI Base Year

II.2.13 In order to capture shifting consumption

pattern of households, the Central Statistics Office

(CSO) revised the base year of CPI to 2012 from

its earlier base of 2010, using the weighting pattern

from the latest consumer expenditure survey (CES),

2011-12 of the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). Changing patterns of consumer

expenditure over the years are reflected in subcategory-

wise weights computed for the new CPI

series (Table II.7).

| Table II.7: Comparison of Weighting Diagrams–Previous and Revised CPI Series |

| (Per cent) |

| Sub-Categories |

Base Year: 2010 |

Base Year: 2012 |

| Rural |

Urban |

Combined |

Rural |

Urban |

Combined |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| Food and Beverages |

56.59 |

35.81 |

47.58 |

54.18 |

36.29 |

45.86 |

| Pan, Tobacco and Intoxicants |

2.72 |

1.34 |

2.13 |

3.26 |

1.36 |

2.38 |

| Clothing and Footwear |

5.36 |

3.91 |

4.73 |

7.36 |

5.57 |

6.53 |

| Housing |

-- |

22.54 |

9.77 |

-- |

21.67 |

10.07 |

| Fuel and Light |

10.42 |

8.40 |

9.49 |

7.94 |

5.58 |

6.84 |

| Miscellaneous |

24.91 |

28.00 |

26.31 |

27.26 |

29.53 |

28.32 |

| Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

‘--’ : CPI (Rural) for housing is not compiled.

Source: Press Release on CPI base year revision, MOSPI, GoI. |

II.2.14 Methodologically, the new series has

incorporated certain improvements: a weighting

pattern based on the modified mixed reference

period (MMRP); internationally accepted

‘classification of individual consumption according

to purpose’ with suitable deviations; and the use

of a geometric mean to compute indices at the

elementary/item level. Along with the prices of

items under the above poverty line (APL) and

below poverty line (BPL) categories, prices of

items under the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY)

are also incorporated in the new series. The

revision has a number of policy implications: lower

sensitivity of the overall index to food price shocks

and idiosyncratic price movements and

incisiveness in identifying sources of inflation at

the item level.

Developments in Inflation: 2015-16 so far

II.2.15 After dipping below 5 per cent in April

2015, CPI inflation edged up to 5.4 per cent in

June driven by the food group owing to a fall in

pulses production during 2014-15 and short-term

pressures in vegetables prices. In July, however,

inflation declined significantly to 3.8 per cent

aided by favourable base effect and ebbing food

price pressures. Excluding food and fuel, inflation

moved up substantially to 5.0 per cent in June

2015 from 4.2 per cent in March 2015 on account

of a broad-based rise in inflation in services

segment, such as health and education as well

as retail fuel price increases captured by the

transport and communication sub-group. It,

however, moderated to 4.5 per cent in July 2015

tracking lower transport costs with recent fall in

fuel prices. Importantly, household inflation

expectations returned to double digits in June

2015 quarter.

II.3 MONEY AND CREDIT

II.3.1 Monetary and credit conditions remained

sluggish through 2014-15 as reflected in the

subdued growth in key monetary and banking

aggregates. The sizeable expansion in Reserve

Bank’s net foreign exchange assets driven by

surges in capital inflows was largely sterilised by

active liquidity management operations.

Consequently, reserve money grew at a subdued

pace, reflecting the slow pace of economic activity

as well as the anti-inflationary monetary policy

stance of the Reserve Bank. Growth of money

supply (M3) also slowed in relation to the preceding

year reflecting the interaction of a number of factors.

First, credit demand was muted reflecting the slack

in the economy. Second, increasing levels of nonperforming

assets (including restructured assets)

imparted an element of risk aversion across the

banking sector. This inhibited credit supply,

especially to stressed sectors such as infrastructure,

with substitution at the margin in loan portfolios in

favour of personal loans and retail lending where

the incidence of non-performing assets (NPAs) was

markedly less. Accordingly, banks tended to

moderate their access to deposits which were also

impacted by inadequate real returns relative to

competing financial assets of households and

corporate entities.

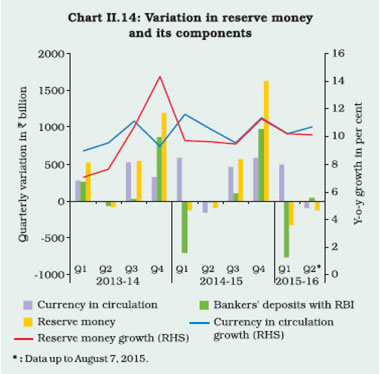

Reserve Money

II.3.2 During 2014-15, reserve money expanded

by 11.3 per cent, down from 14.4 per cent a year

ago. On the components side, currency in

circulation, constituting around 75 per cent of

reserve money, increased by 11.3 per cent. The

pick-up in currency demand from 9.2 per cent a

year ago reflected the interaction of several factors

-election-induced demand for currency and

increased food subsidy (Chart II.14). On the other

hand, growth of bankers’ deposits with the Reserve

Bank slowed to 8.3 per cent, mainly reflecting the deceleration in deposit growth. The maintenance

of reserves evened out across 2014-15 following

the introduction of minimum daily CRR balances of

95 per cent since September 2013. Average daily

excess reserve holdings by the banking sector

declined from around 3 per cent in 2013-14 to 2

per cent in 2014-15, which indicated some

efficiency gains under the new liquidity management

framework introduced in September 2014. Variable

rate auctions have induced some discipline in the

banking system in planning liquidity. A system level

liquidity flux appears to have eased with assurance

on availability of liquidity as needed.

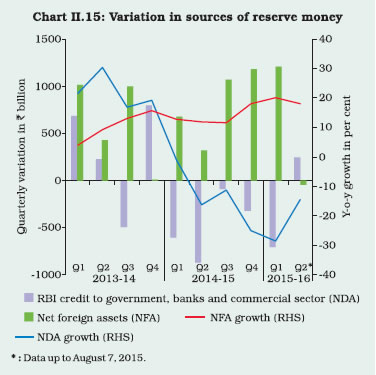

II.3.3 On the sources side, there was a change

in the composition of reserve money in 2014-15 in

terms of net domestic assets (NDA) and net foreign

assets (NFA). With the emergence of India as a

preferred destination for foreign capital, the Reserve

Bank’s foreign exchange operations to mitigate

undue volatility in the foreign exchange market

resulted in a large increase in NFA, injecting around

₹3.2 trillion primary liquidity (reserve money) into

the financial system. Concomitantly, NDA (adjusted

for net non-monetary liabilities) declined by around

₹1.9 trillion to partially sterilise the impact of the Reserve Bank’s forex market operations on reserve

money expansion.

II.3.4 Global financial markets have been roiled

by turbulence associated with divergence in

monetary policy stances in the G3 economies.

During 2014-15, significant shifts in monetary policy

settings were also observed among emerging

economies to manage the effects of G3 monetary

policies on their financial systems transmitted

through capital flows and asset prices as also to

deal with domestic fragilities which restrained growth and made them vulnerable to financial

shocks. Cross-border externalities associated with

the conduct of unconventional monetary policies in

advanced and emerging economies alike occupied

centre-stage in 2014-15 (Box II.3).

Box II.3

Spillovers and Spillbacks

‘Spillovers’ have come to be commonly employed in the

post-unconventional monetary policy (UMP) literature to

refer to the beneficial or damaging effects that a country’s

economic policies can have on other nations. In the more

recent period, the focus has largely been on negative

externalities associated with the Fed’s quantitative easing

(QE) and its widely anticipated normalisation, especially as

the Fed’s forward guidance on it has been data-dependent

and consequently, every incoming data has triggered intense

market reactions on its possible timing. In the event, UMPs

have generated large capital flows to emerging market

economies (EMEs) in an indiscriminate search for yields,

while exit from them has increased the risks of substantial

capital outflows of which the taper tantrum of the summer

of 2013 provided a sinister preview. Empirical evidence

suggests that UMPs have amplified the pro-cyclicality of

capital flows and leverage in EMEs by strengthening the

incentives to engage in maturity transformations, leading to

misalignment with fundamentals with adverse implications

for macroeconomic and financial stability (Fratzscher et al.

2013; Moore et al. 2013). Quite naturally, spillovers from

UMPs have been the subject of acrimonious disharmony

(Taylor 2013). Given the heterogeneity in the structural

characteristics of EMEs, it is important to nuance these

findings and qualify them with country-specific experiences.

For India, an analysis of the impact of spillovers from the

Fed’s QEs using a combination of methodologies, such as

the event study framework, generalised method of moments

(GMM) and vector auto-regressions (VARs) shows that

the largest favourable impact came from QE1 that pushed

capital flows into India, helping finance a widening current

account deficit. QE2, unlike QE1, was associated with

capital outflows from India. These spillovers were transmitted mainly through the portfolio rebalancing channel, followed

by the liquidity channel (Patra et al. 2014).

‘Spillbacks’ are a new entrant in this proliferating body of

work, essentially the boomerang effects from recipient

countries in a vicious loop that in a globally inter-dependent

world adversely affect the source country that caused the

spillovers in the first place. The larger global role played by

EMEs implies that spillbacks from fluctuations in their growth

as a result of shocks in advanced economies can be nontrivial.

VAR specifications suggest that about 50 per cent

of the fluctuations in outputs in advanced economies spill

over onto EMEs of which one-third spill back to advanced

economies (IMF 2014) (Table 1).

| Table 1: Estimated spillovers and spillbacks (per cent) |

| |

US |

Euro Area |

Japan |

UK |

Average |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| EM Spillover |

58.3* |

59.2* |

25.4* |

56.3* |

52.8 |

| EM Spillback |

12.4 |

29.8* |

12.7* |

7.2 |

17.4 |

| EM Spillback/ EM Spillover |

21.3 |

50.4 |

51.1 |

12.8 |

34.4 |

Source: IMF staff calculations.

*: Significant at the 10 per cent level. Estimates of spillovers and

spillbacks from a 1 percentage point increase in growth in advanced

economies (eight quarters after impact). |

Spillback effects are more pronounced for Japan and the

euro area, and less for the United States and the United

Kingdom due to stronger trade linkages (Trade openness

for the US and the UK is relatively far less).

Overall, spillback effects appear to be modest but could

be larger in periods of stress, which in turn might have an adverse impact on the setting of monetary policy. Careful

calibration and clear communication, with cooperation

among policymakers could help in managing spillbacks and

spillovers.

References:

Fratzscher, Marcel, Marco Lo Duca and Roland Straub

(2013), ‘On the International Spillovers of US Quantitative

Easing’, Working Paper Series No. 1557, June.

International Monetary Fund (2014), Spillover Report 2014.

Moore J., S. Nam, M. Suh and A. Tepper (2013),‘Estimating the Impacts of US LSAP’s on Emerging Market Economies’

Local Currency Bond Markets’, Staff Report No. 595,

Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Patra, M.D., J.K. Khundrakpam, S. Gangadaran, Rajesh

Kavediya and Jessica Anthony (2014), ‘Responding to QE

Taper from the Receiving End’, mimeo, RBI.

Taylor John B. (2013),‘International Monetary Policy

Coordination: Past, Present and Future’, Paper prepared

for presentation at the 12th BIS Annual Conference on

‘Navigating the Great Recession: What Role for Monetary

Policy’, Lucerne, Switzerland, June 21.

II.3.5 In response to these global factors affecting

domestic liquidity conditions, the Reserve Bank

endeavoured to contain the expansionary effects

in keeping with its commitment to the glide path of

disinflation. The Reserve Bank, therefore,

appropriately calibrated repo auctions and open market operation (OMO) sales, both outright and

on the Negotiated Dealing System-Order Matching

(NDS-OM) platform to contract NDA and offset the

large increase in NFA (Chart II.15).

II.3.6 Quarterly movements in reserve money in

2014-15 evolved in line with changing drivers of

liquidity and resulting composition shifts in the

Reserve Bank’s balance sheet. On the components

side, except for the seasonal decline in Q2, currency

in circulation increased throughout the year. On the

sources side, the increase in NFA was largely offset

by a decline in NDA in the H1 of 2014-15. In Q4,

however, end year balance sheet adjustments and advance tax payments tightened liquidity conditions,

warranting injection of primary liquidity that

remained largely unsterilised. Consequently,

reserve money growth increased in the last quarter

of 2014-15.

II.3.7 There was also a change in the composition

of NDA during 2014-15 which was in accordance

with modifications in the Reserve Bank’s accounting

policies as recommended by the Technical

Committee formed to review the format of the

balance sheet and the profit and loss account of

the Reserve Bank (Chairman: Shri Y.H. Malegam).

Specifically, net repo operations are now being

recorded under the Reserve Bank’s credit to banks

and commercial sector rather than in its credit to

general government as was done earlier. These

accounting changes are reflected in a decline in

the Reserve Bank’s net credit to the government

and the commensurate increase in its net claim on

banks in 2014-15, though the absolute size of NDA

remains unaffected.

II.3.8 Movements in reserve money influence the

broader measures of money supply through the

money multiplier. In terms of magnitude, the money

multiplier stood at 5.5 in March 2015, unchanged

from its level a year ago. Both the cash deposit ratio

and the cash reserve ratio remained unchanged over

the year, imparting stability to the money multiplier.

Money Supply

II.3.9 The money supply growth slowed down in

2014-15 (Table II.8), mainly reflecting easing

inflation which lowered the demand for money. The

slowdown in money supply in general, and in

aggregate deposits in particular, vis-à-vis 2013-14

has to be seen in the context of the base effect

caused by the swap facility for FCNR(B) deposits

operated by the Reserve Bank during September-

November 2013 which led to high mobilisation of

these deposits in 2013-14. Money supply net of

FCNR(B) deposits was marginally lower in 2014-15

than in the preceding year. However, money supply

improved in the second half of the year (March 2015

over September 2014) in line with the growth in

credit. In tandem, the year-on-year growth in the

liquidity aggregate L1 [sum of the new monetary

aggregate (NM3) and postal deposits] remained

marginally lower than a year ago.

| Table II.8: Monetary Aggregates |

| Item |

Outstanding as on (₹ billion) |

Year-on-year growth rate (in per cent) |

Growth rate (in per cent) |

| March 31,

2015 |

August 7,

2015 |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

2015-16

(as on

August 7) |

FY 15:

H1 |

FY 15:

H2 |

FY16:

H1 |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| I. Reserve Money |

19,285 |

18,815 |

14.4 |

11.3 |

10.1 |

-1.4 |

12.9 |

-2.4 |

| II. Broad Money (M3) |

105,455 |

109,830 |

13.4 |

10.8 |

10.9 |

4.4 |

6.2 |

4.1 |

| III. Liquidity Aggregate (L1) |

106,759 |

110,722# |

11.2 |

10.7 |

11.6# |

4.0 |

6.5 |

3.7# |

| IV. Major Components of M3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IV.1. Currency with the Public |

13,863 |

14,251 |

9.2 |

11.3 |

9.5 |

3.4 |

7.6 |

2.8 |

| IV.2. Aggregate Deposits |

91,446 |

95,567 |

14.1 |

10.6 |

11.2 |

4.4 |

5.9 |

4.5 |

| V. Major Sources of Money Stock (M3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V.1. Net Bank Credit to Government |

30,062 |

33,781 |

12.4 |

-1.3 |

10.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.8 |

12.4 |

| V.2. Bank Credit to Commercial Sector |

70,396 |

71,627 |

13.7 |

9.2 |

9.0 |

2.3 |

6.8 |

1.7 |

| V.3. Net Foreign Exchange Assets of the Banking Sector |

22,506 |

23,664 |

17.6 |

17.0 |

16.0 |

3.9 |

12.6 |

5.1 |

| M3 Net of FCNR(B) |

102,782 |

107,009 |

11.5 |

11.0 |

11.1 |

4.4 |

6.3 |

4.1 |

| M3 Multiplier |

5.5 |

5.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| M3 Velocity |

1.25 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-: Not available;

#: Data pertain to July 2015.

Note: 1. Data are provisional.

2. FY 15: H1: Growth rate of September 2014 over March 2014,

FY 15: H2: Growth rate of March 2015 over September 2014, and

FY 16: H1: Growth rate of August 7, 2015 over March 31, 2015. |

II.3.10 Growth in aggregate deposits, which forms

a major component of money supply, has generally

been declining over the years in line with a decrease

in the saving rate of the economy. In addition,

slowdown in credit growth led to lower deposit

mobilisation by banks. The growth in aggregate

deposits decelerated to 10.6 per cent in 2014-15

from 14.1 per cent a year ago. On the sources side,

a decline in banks’ credit growth to the commercial

sector was one of the key drivers. Another major

constituent from the sources side, that is, net bank

credit to the government declined during the year

mainly due to reduction in the Reserve Bank’s

holding of government securities (G-secs).

Commercial banks, on the other hand, stepped up

their investment in G-secs in view of credit

deceleration during the year.

II.3.11 The velocity of money (Chart II.16), which

declined over the past six decades hovered around 1.25, indicating stability of the financial system in

the post-crisis years. Another commonly referred

indicator of financial deepening - M3 to GDP

ratio - which is a reciprocal of velocity, stood at

around 80.

CREDIT

II.3.12 Non-food credit growth decelerated

sharply in 2014-15 to 9.3 per cent (y-o-y), with

incremental non-food credit declining to ₹5.5

trillion from ₹7.3 trillion in the previous year. A

host of factors weighed down on credit off-take,

including lower corporate sales, softening of

inflation rate, risk aversion by banks due to rise

in non-performing loans, and procedural delays

in debt recovery (Box II.4). Further, with the

availability of alternative sources, both domestic and foreign, corporates switched some of the

demand for financing to non-bank sources. Sale

of significantly larger amount of non-performing

loans (₹317 billion) by banks to asset

reconstruction companies (ARCs) during 2014-

15 also contributed to a deceleration in bank

credit. Food credit also registered a decline of

4.1 per cent during the year, despite some pickup

in procurement, as a result of enhanced food subsidies which increased by 28.1 per cent in

2014-15.

Box II.4

Factors Underlying Recent Credit Slowdown: An Empirical Exploration

Credit plays an important role in economic development,

particularly in a bank-based financial system. Countries which

experienced high growth since 2000 also witnessed a surge

in private credit (Claessens et al. 2011). An empirical analysis

also suggests that credit growth is positively influenced by

deposit growth, GDP growth, easy global liquidity conditions

and exchange rate depreciation, whereas inflation dampens

real credit growth (Guo and Stepanyan 2011). In India’s bankbased

financial system, credit plays an important role in the

overall growth dynamics.

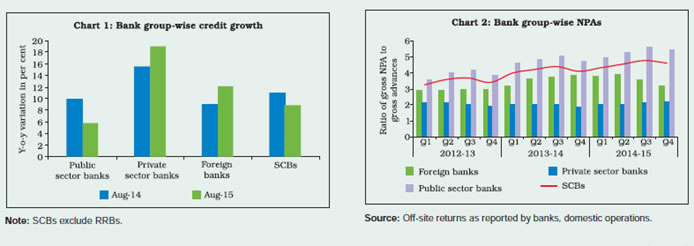

Asset quality concerns resulting in risk aversion are

considered to be one of the major factors underlying the

current slowdown in credit. Public sector banks, which

recorded higher NPA ratios, experienced a sharp decline in

credit growth. On the other hand, private sector banks with

lower NPA ratios, posted higher credit growth (Chart 1 and

2). At the aggregate level, the NPA ratio and credit growth

exhibited a statistically significant negative correlation of 0.8,

based on quarterly data since 2010-11.

Applying the methodology of Guo and Stepanyan (2011) to

Indian quarterly data from June 1997 to September 2014,

non-food credit was found to be influenced by lagged real

GDP growth in a positive and statistically significant manner.

The cost of credit proxied by the overnight call rate, as

expected, had a negative impact on credit growth. The impact

of the interest rate was found to be strong up to two lags,

reflecting transmission lags. In line with the theory, the

coefficient of gross fiscal deficit (GFD) of the Centre had a

negative sign, indicating crowding out effects of fiscal deficit

in market for bank credit. Finally, the change in outstanding

commercial papers (CPs), a proxy for an alternative source

of funds, had a negative and significant coefficient.

Adjusted R2=0.30; *: Significant at 5 per cent;

NPAs were not included in the regression as the series had multiple

structural breaks.

Note: 1. BC=q-o-q seasonally adjusted growth in bank credit;

WCMR=quarterly weighted average call rate; GDP= q-o-q seasonally

adjusted growth in GDP (base: 2004-05); GFD: quarterly GFD (Centre)

as per cent of GDP at current market price; CP_out: q-o-q seasonally

adjusted growth in CP outstanding.

2. The results were subjected to standard robustness checks.

Thus economic activity, cost of credit, the fiscal position and

competitive alternative funding sources turned out to be major

factors affecting credit behaviour in India.

References:

Claessens, S., M. A. Koseand M.E. Terrones (2011), ‘How Do

Business and Financial Cycles Interact?’, IMF Working Paper,

No. WP/11/88.

Guo K. and V. Stepanyan (2011), ‘Determinants of Bank Credit

in Emerging Market Economies’, IMF Working Paper

WP/11/51.

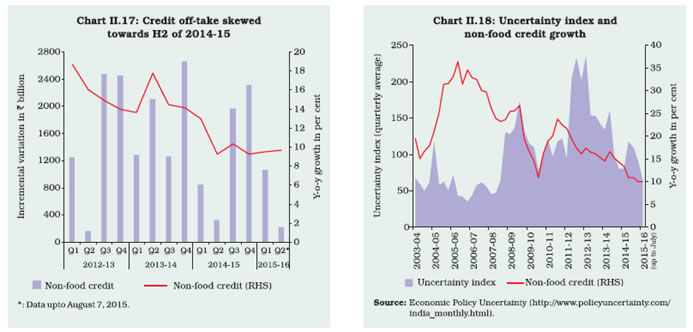

II.3.13 With the deceleration in non-food credit

growth on a year-on-year basis, nearly 80 per cent

of the incremental credit off-take during 2014-15

took place in the second half of the year, reflecting

the improving economic environment (Charts II.17

and II.18). Non-food credit growth increased to 7.1 per cent in H2 of 2014-15 from 2.0 per cent in H1,

representing an improvement of 5 percentage

points in H2 compared with 0.6 percentage point

increase a year ago.

II.3.14 In order to create more space for banks to

expand credit to the productive sectors of the

economy, the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) was

reduced in three stages from 23 per cent to 21.5

per cent of net demand and time liabilities (NDTL)

during 2014-15. However, banks continued to

maintain SLR investments around 28 per cent of

NDTL, the buffer providing access to collateralised

borrowings from the wholesale funding market and

the Reserve Bank. Maintaining excess SLR

securities also helped banks to weather the impact

of the current slow phase of the economic cycle on

their balance sheets and earnings.

II.3.15 Data on sectoral deployment of credit, which

constitutes about 95 per cent of total bank credit

by SCBs, indicate that deceleration in credit off-take in 2014-15 was more pronounced with respect to

the industry and services sectors, which together

constituted about 68 per cent of total non-food

credit. Credit growth in the services sector was

weighed down by its major components: trade and

non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) that

accounted for nearly 48 per cent of the total credit

to the services sector. In the industrial sector,

growth slowed down across sectors, particularly for

infrastructure, basic metals and food processing.

The sectors which witnessed lower incidence of

NPAs such as personal loans saw higher growth

during the year.

II.3.16 Infrastructure accounts for nearly one-third

of the credit to the industrial sector. Its main

components are power and roads, constituting 60

and 18 per cent of the total infrastructure credit

respectively. While deceleration in credit to the

power sector was modest, the slowdown was sharp

with respect to roads in 2014-15 (Table II.9).

| Table II.9: Trends in Credit Deployment to Select Sectors |

| (Variation in per cent) |

| |

Outstanding at

20-Mar-2015

(₹ billion) |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

2015-16 |

| H1 |

H2 |

Year |

H1 |

H2 |

Year |

H1 |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Non-food Credit (1 to 4) |

60,030 |

6.8 |

6.3 |

13.6 |

2.2 |

6.2 |

8.6 |

1.1 |

| 1. Agriculture & Allied Activities |

7,659 |

3.4 |

9.2 |

12.9 |

8.8 |

5.7 |

15.0 |

3.8 |

| 2. Industry |

26,576 |

6.3 |

6.1 |

12.8 |

-0.1 |

5.7 |

5.6 |

-1.0 |

| Of which: |

9,245 |

8.8 |

5.3 |

14.6 |

4.3 |

6.0 |

10.5 |

1.0 |

| (i) Infrastructure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Of which: (a) Power |

5,576 |

10.7 |

5.8 |

17.1 |

6.6 |

7.5 |

14.5 |

2.8 |

| (b) Telecommunications |

919 |

-0.6 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

-3.6 |

8.0 |

4.2 |

-2.9 |

| (c) Roads |

1,687 |

9.2 |

10.1 |

20.2 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

6.9 |

-0.7 |

| (ii) Basic Metal & Metal Product |

3,854 |

7.2 |

7.1 |

14.9 |

-0.4 |

7.2 |

6.8 |

-0.6 |

| (iii) Food Processing |

1,715 |

3.5 |

20.4 |

24.6 |

-2.6 |

20.4 |

17.3 |

-6.2 |

| 3. Services |

14,131 |

9.0 |

6.5 |

16.1 |

-1.2 |

6.9 |

5.7 |

1.4 |

| 4. Personal Loans |

11,663 |

7.5 |

4.6 |

12.5 |

8.0 |

6.9 |

15.5 |

4.0 |

| Note: Latest available data for H1 of 2015-16 are up to June 2015. |

II.3.17 During 2015-16 so far (up to August 7),

credit off-take seems to be picking up reflecting

an improving economic and policy environment,

though it is too early for a conclusive evidence.

Incremental non-food credit stood around

₹1,282 billion as against ₹963 billion during the

corresponding period last year. Data on sectoral

deployment (up to June 2015) reveal a

significant pick-up in services mainly supported

by trade and professional services, while

industry registered a decline. Within industry,

although credit to infrastructure shows signs of

pick-up, that to roads continues to be weak

(Chart II.19).

Non-bank funding

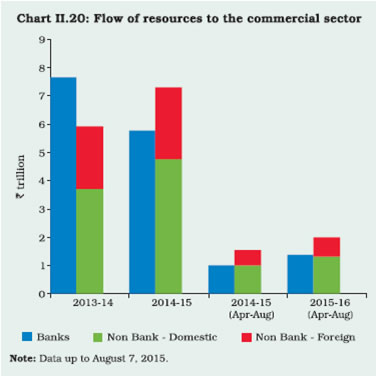

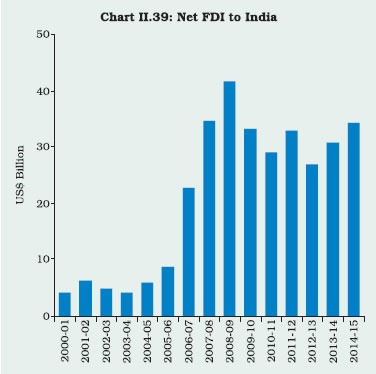

II.3.18 Slowdown in credit growth dragged down

the overall flow of financial resources to the

commercial sector in 2014-15, despite higher

recourse to non-bank sources of funds (Chart

II.20). Amongst the non-bank domestic sources, net issuance of CPs witnessed a four-fold

increase during the year, mainly attributable to

competitive pricing vis-á-vis banks’ lending

rates. Further, FDI inflows remained strong and

accounted for a major chunk of the non-bank

foreign resources to the commercial sector.

Reliance on non-bank sources continues during

2015-16 so far (up to August 7) amidst

comfortable liquidity conditions and competitive

rates.

II.3.19 Regime shifts in the conduct of monetary

policy shaped monetary and credit conditions in

2014-15. Money supply and other key monetary

aggregates decelerated in line with underlying

macroeconomic activity. Overall, credit growth was

subdued during 2014-15 owing to various factors,

such as risk aversion by banks due to rising NPAs

and alternative and cheaper sources of non-bank

funding, though there was some evidence that a

turnaround in the second half of the year might have

set in.

II.4 FINANCIAL MARKETS

Global Financial Markets

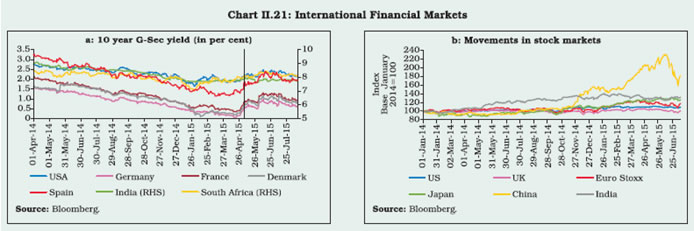

II.4.1 International financial markets remained

generally upbeat during 2014-15, lifted by

expectations of a relaxed approach of the US

Federal Reserve to monetary policy normalisation,

quantitative easing by the European Central Bank

(ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and decline in

crude oil prices. Government bond yields for most

of the countries were historically low with some

European countries even experiencing negative

yields (Chart II.21a). A number of stock markets

also reached historical highs during 2014-15 as

fears about US monetary policy rates lifting off

receded and the ECB and the BoJ enhanced their

asset purchase programmes. However, markets

experienced some volatility in mid-October 2014

on account of uncertainty on the global recovery,

a slew of weak data from the US and the euro area

and continuing geo-political tensions in the Middle

East. Again in the second half of December 2014,

markets were affected by the Ukrainian crisis

followed by the Russian currency crisis and large

exchange rate depreciation in Venezuela and

Argentina (Chart II.21b).

II.4.2 The US dollar index, which measures the

dollar’s movement against other major currencies,

strengthened by 23 per cent from 80.1 at end-March 2014 to 98.4 at end-March 2015. While it

strengthened primarily on account of a robust US

economic recovery, weak economic recovery in the

euro zone and Japan during the year resulted in

the euro and the Japanese yen depreciating against

the US dollar. In January 2015, as ECB prepared

to announce quantitative easing, the Swiss National

Bank (SNB) abandoned its cap on the Swiss franc/

euro exchange rate which led to heightened

exchange rate volatility. During Q4 of 2014-15, a

number of emerging markets and developing

economies (EMDEs) reduced their policy rates to

support economic growth. Interventions in foreign

exchange markets to address depreciating

pressures also increased.

II.4.3 In May 2015, markets were surprised by the

global bond sell-off that started in Germany as the

10-year German Bund yield increased to intra-day

high of 0.77 per cent on May 7 from 0.05 per cent

on April 17, 2015. Concerns over Greek debt,

sustained increase in crude oil prices and profit

booking quickly transmitted to US treasury bills as

well as emerging market economies.

II.4.4 During June 2015, movements in

international financial markets were abuzz with

uncertainty relating to the outcome of Greek debt

negotiations and meltdown in the Chinese stock

market. However, in July financial markets received support from the announcement of the bailout deal

between Greece and the euro zone members and

signing of the nuclear deal between Iran and major

world powers. In August, the global financial

markets were shaken by China’s decision to

devalue its currency by around 2 per cent.

Indian Financial Markets

II.4.5 Both domestic and global cues were at play

in buoying Indian financial markets during 2014-15.

Equity markets reached all-time highs during the

year. Money markets were stable and liquid with

call money rate evolving tightly around the policy

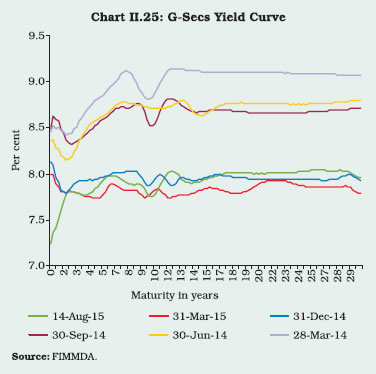

repo rate. Yields on government securities (G-secs)

declined gradually and activity in the corporate bond

market registered an increase mainly due to

primary issuances.

Money Market

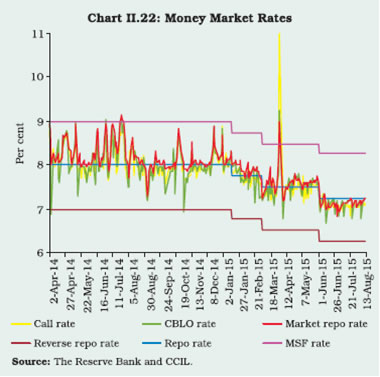

II.4.6 Overnight call money rates remained closely

aligned to the policy repo rate, with active liquidity

management operations under the revised liquidity

management framework, except adjustment for the

year-end window dressing. Money market rates

declined in Q4 in sync with cuts in the policy rate

(Chart II.22). With deposit growth generally

remaining above credit growth during the year,

structural liquidity conditions remained comfortable.

During 2015-16 so far, call money rates have

remained aligned to the policy repo rate with money

market rates declining after the cut in policy rate on

June 2, 2015.

II.4.7 The spread of the daily weighted average

call rate (excluding Saturdays) over the policy rate

narrowed down significantly during 2014-15 from

30 basis points (bps) to 18 bps after the adoption

of the revised liquidity management framework in

September 2014. The spread further narrowed

down to 16 bps during 2015-16 (upto August 14).

The spread of collateralised rates (CBLO and

market repo) also narrowed down during this period, indicating synchronised movement among overnight

money market rates. The collateralised segment

continued to attract a major portion of the turnover

in the overnight market, with the uncollateralised

(call money) segment registering relatively thin

volumes, rendering it susceptible to bouts of

volatility. A large part of the assured liquidity support

under the Reserve Bank’s liquidity adjustment

facility (LAF) is being offered through variable rate

term repos with one of its main objectives being

development of the term money market.

Notwithstanding these initiatives, the turnover in the

term money market has remained muted.

Issuance of CDs and CPs

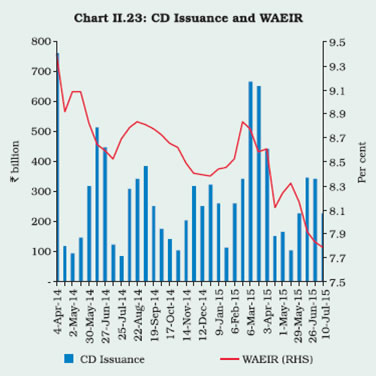

II.4.8 The average fortnightly issuance of

certificates of deposits (CDs) decreased to ₹297

billion during 2014-15 from ₹306 billion during the

previous year (Chart II.23). The easing of liquidity

conditions, coupled with a reduction in the policy

rate and relatively lower issuances of CDs by banks

on the back of subdued credit off-take, led to a

decrease in the weighted average effective interest

rate (WAEIR) on CDs from 9.74 per cent at end-

March 2014 to 8.58 per cent at end-March 2015. The easing trend has continued during 2015-16 so

far with WAEIR declining further to 7.79 per cent

by July 10, 2015.

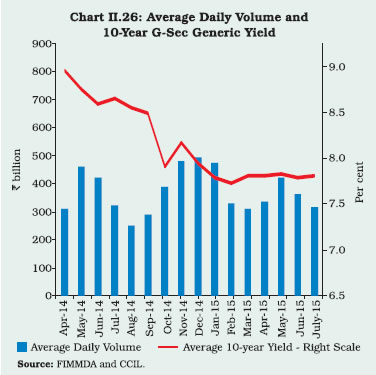

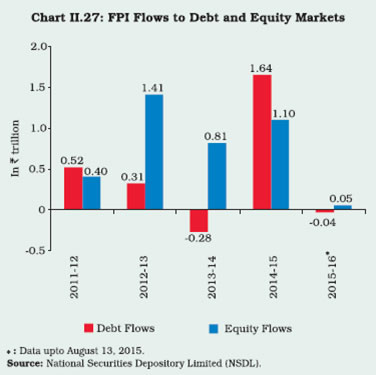

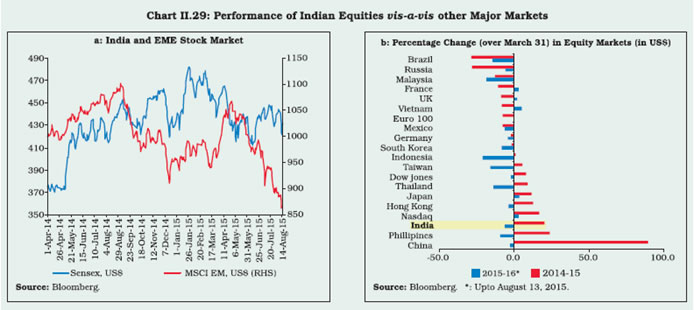

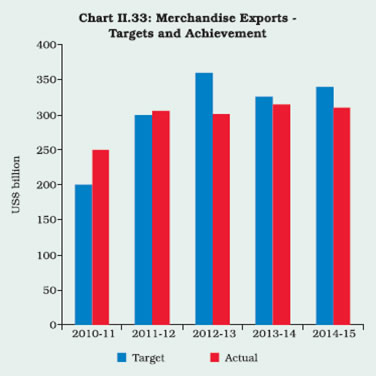

II.4.9 The average fortnightly issuance of