A Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA) was signed between the Government of India and the Reserve

Bank on February 20, 2015. The policy rate was reduced by 75 bps during 2015-16 and 25 bps during 2016-17 so

far, in support of an accommodative policy stance. The target for CPI inflation below 6 per cent by January 2016

was met and the focus has shifted to attaining the inflation target of 5 per cent by the end of 2016-17. Effective

liquidity management kept the weighted average call rate (WACR) tightly around the policy repo rate during

2015-16. In April 2016, the liquidity management framework was revised to progressively move to a position closer to

neutrality. The policy rate corridor around the repo rate was narrowed to +/- 50 bps. The Reserve Bank introduced

the Marginal Cost of Funds based Lending Rate (MCLR) system effective April 1, 2016. The Union Budget

2016-17 announced the constitution of a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) by amending the RBI Act, 1934. The

amendment to the Act was notified in the Gazette of India on May 14, 2016 and came into force on June 27, 2016.

III.1 The conduct of monetary policy during

2015-16 was steered by the MPFA signed between

the Government of India and the Reserve Bank on

February 20, 2015 (Box III.1). Empowered by the

MPFA, the Reserve Bank set out an agenda for its

monetary policy operations: entrenching a durable

disinflationary process to take consumer price

index (CPI) inflation to the targets set for January

2016 and March 2017; improving transmission of

the policy rate to bank lending rates by ensuring

appropriate liquidity management consistent

with the monetary policy stance; and dampening

volatility of the WACR and other money market

rates around the repo rate, i.e., securing the first

leg of monetary transmission.

Agenda for 2015-16: Implementation Status

Disinflation

III.2 The first bi-monthly policy statement

of the Reserve Bank for 2015-16 maintained accommodative stance for monetary policy while

keeping focus on a gradual and durable disinflation

path that would take the CPI inflation below 6 per

cent by January 2016. The assessment at that time

was that inflation would be at 5.8 per cent by the

end of the year. Upside risks to the forecast such

as less than normal rainfall, large administered

price revisions, faster closing of the output gap and

possible geo-political spill-overs were expected

to be largely offset by downside risks originating

from global deflationary/disinflationary tendencies

and a soft outlook on global commodity prices.

Accordingly, the policy rate was kept unchanged

while awaiting transmission of past rate reductions

into banks’ lending rates, policy efforts to improve

food supply management and the unravelling of

global developments including the normalisation

of the US monetary policy. In June 2015, even as

concerns about a sub-normal south west monsoon

and its implications for food inflation remained, the

Reserve Bank reduced the policy repo rate by 25 bps, considering the weak investment climate

and the need to mitigate supply constraints. In

August 2015, the policy rate was kept unchanged

while awaiting clarity on domestic and global

developments and further transmission by banks.

Box III.1

Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA)

With the signing of the MPFA between the Government of

India and the Reserve Bank on February 20, 2015, flexible

inflation targeting (FIT) has been formally adopted in India.

Under the MPFA, the objective of monetary policy is to

primarily maintain price stability while keeping in view the

objective of growth. The Reserve Bank was to bring CPI

inflation below 6 per cent by January 2016. The target for

2016-17 and all subsequent years was set at 4 per cent with

a band of +/- 2 per cent. The MPFA also requires the Reserve

Bank to establish an operating target and an operating

procedure for monetary policy through which the operating

target is to be achieved. The Reserve Bank shall be seen to

have failed to meet the target if inflation remains above 6 per

cent or below 2 per cent for three consecutive quarters. In

such circumstances, the Reserve Bank is required to provide

the reasons for the failure, and propose remedial measures

and the expected time to return inflation to the target. The

Reserve Bank shall publish a document explaining the

sources of inflation as well as forecasts of inflation for the

next six to eighteen months.

The Reserve Bank has been publishing a bi-annual

Monetary Policy Report (MPR) since September 2014,

which provides forecasts of inflation and growth as well as

an assessment of the overall macroeconomic conditions.

The MPR also sets out the operating target and gives details

of the operating procedure of monetary policy and any

changes thereto.

With the amendment to the RBI Act on May 14, 2016, several

provisions of MPFA were subsumed in the amended Act. The

Central Government, in consultation with the Reserve Bank,

has notified the inflation target of 4.0 per cent (with 6.0 per

cent and 2.0 per cent as the upper and lower tolerance levels,

respectively) in the Official Gazette on August 5, 2016. This

inflation target is applicable for the period from August 5, 2016

to March 31, 2021. Moreover, factors that constitute a failure

to achieve the inflation target – i.e., if the average inflation is

more/less than the upper/lower tolerance level for three

consecutive quarters – have also been defined and notified

in the Official Gazette on June 27, 2016.

References:

RBI (2014), “Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and

Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework” (Chairman: Urjit

R. Patel), January.

Government of India (2015), “Agreement on Monetary Policy

Framework between the Government of India and the Reserve

Bank of India”, February.

III.3 By September 2015, the receding

inflationary pressure emanating from benign

cereal prices and moderation in international

crude oil prices opened up space for monetary

policy action. The Reserve Bank front-loaded the

policy action by effecting a 50 bps cut in the policy

repo rate to boost domestic demand and stimulate

investment.

III.4 From September onwards, inflation began

rising prompting status quo on the policy rate

in December 2015. In February 2016, with a

softening in food and fuel inflation, it became clear that the January 2016 disinflation target would be

met and the subsequent data release which placed

CPI inflation for January 2016 at 5.7 per cent

confirmed this. With the target for January 2016

achieved, the focus of monetary policy shifted to

attaining the inflation target of 5 per cent by the end

of fiscal year 2016-17. Based on an assessment

that the target of 5 per cent inflation by March

2017 was achievable, particularly when the Union

Budget 2016-17 adhered to fiscal consolidation

and announced measures to re-invigorate the

rural economy, upgrade the social and physical

infrastructure, deepen institutional reforms and

improve the environment for business, the policy

rate was reduced further by 25 bps to 6.5 per cent

in April 2016, the lowest since March 2011. The

policy rate was kept unchanged in June 2016 in

view of uncertainties due to larger than seasonal inflationary pressures emanating from food items

and reversal in commodity prices. Continuing with

the accommodative stance, a status quo on the

policy repo rate was maintained in August 2016 as

a sharper-than-anticipated increase in food prices

pushed up the projected trajectory of inflation over

the rest of the year.

Operating Framework

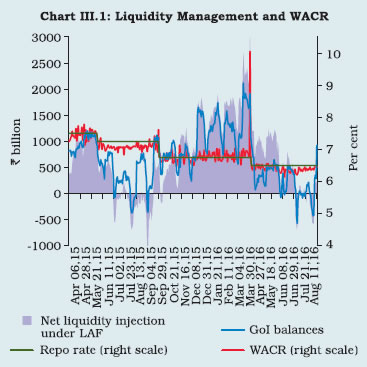

III.5 The goal of the operating framework of

monetary policy is to modulate liquidity conditions

in order to align the operating target – the WACR

– closely with the policy repo rate. During

2015-16, a considerable flux in autonomous liquidity

flows necessitated a pro-active assessment of

liquidity conditions and nimble responses through

a combination of regular facilities and fine-tuning

operations in the form of variable rate repo/reverse

repo auctions, drawing upon the revised liquidity

framework instituted in September 2014 (Chart

III.1). Liquidity conditions generally remained tight

during the second half of the year due to festival

related currency requirements and advance tax

outflows in Q3, followed by balance sheet

considerations and restraint in government spending in Q4. Accordingly, the daily recourse to

the Reserve Bank for liquidity which averaged ₹ 1.2

trillion during the second half of 2015-16 through

all liquidity windows, peaked at ₹ 3 trillion at end-

March 2016. The end-year spike in WACR was due

to the usual build-up of cash balances by banks

and the government. Effective liquidity management,

however, kept the WACR within +/- 10 bps and +/-

20 bps of the repo rate for 36 per cent and 79 per

cent of the total number of trading days, respectively,

during 2015-16.

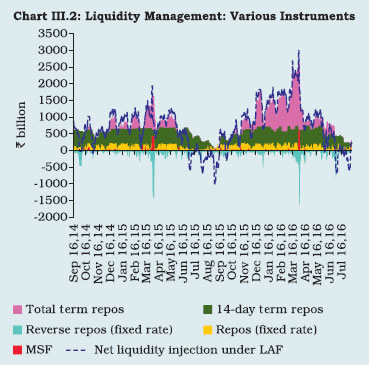

III.6 With the institution of the revised liquidity

management framework, the role of term repo

auctions under the liquidity adjustment facility

(LAF) has become significant. Normal 14-day and

fine tuning term repos of varying tenors ranging

from 2 to 56-day accounted for about 90 per

cent of the average net liquidity injection under

the LAF during the year (Chart III.2). Since July

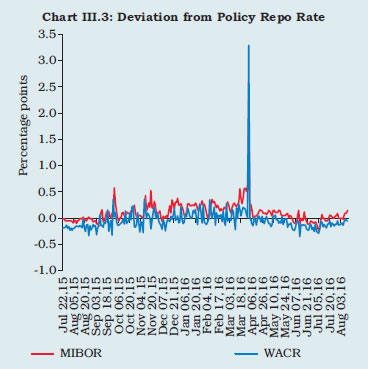

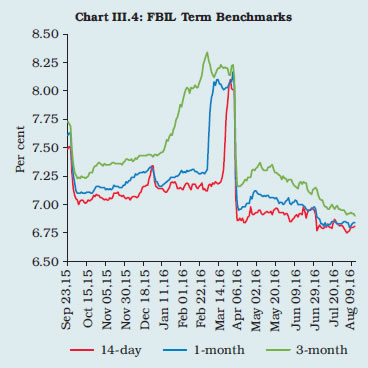

22, 2015, the Financial Benchmark India Private

Limited (FBIL) has started compiling the Mumbai

Inter-Bank Offer Rate (MIBOR) based on actual

data of the interbank call market transactions

covering a one hour time span – from 9.00 a.m. to 10.00 a.m. Given the market microstructure, thick

trading in the first hour usually elevates MIBOR

above WACR (Chart III.3). The FBIL has started

generating quote-based term benchmarks, but

their use in pricing of financial products and

transactions is yet to pick up (Chart III.4).

III.7 In April 2016, the liquidity management

framework was revised in a move to progressively lower the average ex ante liquidity deficit to a

position closer to neutrality. The Reserve Bank

assured the market of meeting the requirements

of durable liquidity and then using its fine-tuning

operations to make short-term liquidity conditions

consistent with the stated policy stance.

Accordingly, in Q1 of 2016-17 the Reserve Bank

injected permanent liquidity of ₹ 805 billion through

open market operations (outright), more than

offsetting the impact of currency leakage of ₹ 696

billion during the same period. For ensuring non-disruptive

FCNR(B) redemptions, the Reserve

Bank pro-actively injected ₹ 100 billion through

open market purchase auction on August 11,

2016. With a view to further minimising volatility

in WACR, as also easing liquidity management for

banks without abandoning liquidity discipline, the

minimum daily maintenance of the cash reserve

ratio (CRR) was lowered from 95 per cent of the

requirement to 90 per cent effective April 16,

2016. Furthermore, the policy rate corridor around

the repo rate was narrowed from +/-100 bps to

+/- 50 bps.

III.8 During 2015-16, as a part of the phased

implementation of the liquidity coverage ratio

(LCR), the minimum required high quality liquid

assets (HQLA) was raised from 60 per cent to

70 per cent of the total net cash outflow over the

next 30 calendar days under the stress scenario

effective January 01, 2016, which correspondingly

limited the capacity of banks to use the excess

statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) securities to access

collateralised liquidity from money markets and

the Reserve Bank. Recognising the scope for

providing greater flexibility to banks within the

prescribed SLR, effective February 11, 2016, the

Reserve Bank allowed banks to reckon additional

government securities held by them up to three

per cent of their NDTL within the mandatory SLR

requirement as level 1 HQLA for the purpose of

computing their LCR on top of the five per cent permitted in November 2014. On July 21, 2016,

additional headroom equivalent to 1 per cent of

NDTL was provided within the prescribed SLR.

Together, the total carve-out from SLR available

to banks stands at 11 per cent of their NDTL,

including 2 per cent of NDTL available under MSF.

Monetary Policy Transmission

III.9 In response to the reduction in the policy

repo rate by 150 bps during January 15, 2015

through April 05, 2016, the median base rate of

banks declined by 60 bps as against a higher

decline of 92 bps in median term deposit rates,

reflecting banks’ preference to protect profitability

in the wake of deteriorating asset quality and

higher provisioning (Table III.1). The weighted

average lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee

loans declined by 100 bps (up to June 2016),

significantly more than the decline of 65 bps in

WALR on outstanding rupee loans.

Sectoral Lending Rates

III.10 Since December 2014, lending rates

across various sectors (except credit card) have

declined in the range of 16-110 bps, reflecting the varied credit conditions and risk appetite of

banks (Table III.2). Interest rates on fresh rupee

loans sanctioned for housing – personal and

commercial – declined more than that of the

respective categories of vehicle loans (Table III.3).

| Table III.1: Deposit and Lending Rates of

SCBs (Excluding RRBs) |

| (Per cent) |

| End-Month |

Repo Rate |

Term Deposit Rates |

Lending Rates |

| Median Term

Deposit Rate |

WADTDR |

Median

Base

Rate |

WALR

- Outstanding Rupee

Loans |

WALR

- Fresh

Rupee

Loans |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| Dec-14 |

8.00 |

7.55 |

8.64 |

10.25 |

11.84 |

11.45 |

| Mar-15 |

7.50 |

7.50 |

8.57 |

10.20 |

11.76 |

11.07 |

| Jun-15 |

7.25 |

7.22 |

8.43 |

9.95 |

11.61 |

11.03 |

| Sep-15 |

6.75 |

7.02 |

8.03 |

9.90 |

11.53 |

10.77 |

| Dec-15 |

6.75 |

6.77 |

7.83 |

9.65 |

11.31 |

10.59 |

| Mar-16 |

6.75 |

6.77 |

7.73 |

9.65 |

11.20 |

10.47 |

| Jun-16 |

6.50 |

6.63 |

7.52 |

9.65 |

11.19 |

10.45 |

| Variation (Percentage Points) (Jun-16 over Dec-14) |

-1.50 |

-0.92 |

-1.12 |

-0.60 |

-0.65 |

-1.00 |

| WADTDR: Weighted average domestic term deposit rate. |

Table III.2: Sector-wise WALR of SCBs (Excluding RRBs) - Outstanding Rupee Loans

(at which 60 per cent or more business is contracted) |

| (Per cent) |

| End-Month |

Agriculture |

Industry (Large) |

MSMEs |

Infra-structure |

Trade |

Profes- sional

Services |

Personal Loans |

Rupee Export Credit |

| Housing |

Vehicle |

Education |

Credit Card |

Other |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

| Dec-14 |

10.93 |

12.95 |

13.05 |

13.05 |

13.09 |

12.39 |

10.76 |

11.83 |

12.90 |

37.86 |

14.24 |

12.16 |

| Mar-15 |

10.96 |

12.80 |

12.91 |

12.89 |

13.07 |

12.46 |

10.99 |

11.62 |

12.87 |

37.88 |

13.94 |

12.04 |

| Jun-15 |

10.76 |

12.62 |

12.36 |

12.24 |

12.52 |

12.03 |

10.81 |

11.39 |

12.58 |

37.87 |

13.75 |

11.63 |

| Sep-15 |

10.73 |

12.39 |

12.43 |

12.18 |

12.51 |

12.17 |

10.63 |

11.49 |

12.51 |

37.34 |

13.24 |

11.89 |

| Dec-15 |

10.51 |

12.47 |

12.34 |

12.25 |

12.72 |

12.74 |

10.36 |

11.00 |

12.35 |

34.04 |

13.86 |

11.60 |

| Mar-16 |

10.74 |

12.36 |

12.25 |

12.06 |

12.50 |

11.81 |

10.56 |

11.65 |

12.48 |

38.00 |

13.90 |

11.46 |

| Jun-16 |

10.77 |

12.17 |

12.08 |

12.20 |

11.99 |

11.64 |

10.50 |

11.39 |

12.32 |

38.26 |

13.96 |

11.17 |

| Variation (Percent- age Points) (Jun-16 over Dec-14) |

-0.16 |

-0.78 |

-0.97 |

-0.85 |

-1.10 |

-0.75 |

-0.26 |

-0.44 |

-0.58 |

0.40 |

-0.28 |

-0.99 |

| MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. |

| Table III.3: WALR of Select Sectors of SCBs

(Excluding RRBs) - Fresh Rupee Loans

Sanctioned |

| (Per cent) |

| End-Month |

Personal |

Commercial |

| Housing |

Vehicle |

Housing |

Vehicle |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Dec-14 |

10.53 |

12.29 |

11.74 |

12.53 |

| Mar-15 |

10.47 |

12.42 |

12.05 |

12.30 |

| Jun-15 |

10.10 |

12.53 |

12.06 |

12.29 |

| Sep-15 |

10.22 |

12.24 |

11.79 |

11.90 |

| Dec-15 |

10.02 |

11.97 |

11.08 |

11.64 |

| Mar-16 |

9.79 |

11.99 |

11.15 |

11.21 |

| Jun-16 |

9.64 |

11.80 |

10.53 |

11.49 |

| Variation (Percentage Points) (June-16 over Dec-14) |

-0.89 |

-0.49 |

-1.21 |

-1.04 |

Experience of the MCLR System

III.11 As set out in the agenda for 2015-16, the

Reserve Bank introduced the Marginal Cost of

Funds based Lending Rate (MCLR) system for

scheduled commercial banks (excluding RRBs),

effective April 1, 2016 whereby all new rupee

loans sanctioned and credit limits renewed would

be priced with reference to the MCLR.

III.12 Under the MCLR system, banks determine

their benchmark lending rates linked to marginal

cost of funds which is more sensitive to changes

in the policy rate, unlike the earlier base rate system

where banks adopted different methodologies

(average/marginal/blended principles) for

computing their cost of funds. MCLR consists of

four components: (a) marginal cost of funds

(marginal cost of borrowings comprising deposits

and other borrowings, and return on net worth), (b)

negative carry on account of CRR, (c) operating

costs and (d) term premium. The MCLR plus spread

is the actual lending rates for borrowers. The spread

comprises of only two components, viz., business

strategy and credit risk premium.

III.13 Under the MCLR system, transmission to

WALR is expected to improve on the assumption that the marginal cost of funds is more sensitive to

changes in the policy rate than the average cost of

funds. As expected, the MCLR for the overnight

segment, one year segment and up to three-year

segment (as on July 31, 2016) was lower by 70 bps,

25 bps and 36 bps, respectively, than the base rate

of 9.65 per cent (Table III.4).

III.14 There has hardly been any transmission

of a reduction in the policy rate to the actual

lending rates charged to customers during

2016-17 so far (up to June). While the cost of

funding by banks has declined somewhat leading

to a decline in shorter maturity MCLR, there has

been an increase in the term premia in respect

of term loans of one year and above, thereby attenuating the transmission to actual lending

rates charged to customers. Moreover, banks may

have been loading (i) a higher credit risk premia on

their new customers in order to attain their desired

return on net worth in a rising NPA environment;

and/or (ii) a higher strategic risk premia on their

riskier loans as part of their business strategy

to reorient their lending operations towards less

risky activities. The consequent rise in the spread

is reflected in a near unchanged WALR in respect

of both outstanding and fresh rupee loans during

2016-17 so far (up to June).

| Table III.4: MCLR and Base Rate of SCBs

(Excl. RRBs) |

| (Per cent) |

| Tenor |

Median MCLR |

Variation [col. 3-col. 2] (Percentage

Points) |

| April 04, 2016 |

July 31, 2016 |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| Overnight |

9.05 |

8.95 |

-0.10 |

| 1-Month |

9.20 |

9.03 |

-0.17 |

| 3-Month |

9.30 |

9.20 |

-0.10 |

| 6-Month |

9.40 |

9.28 |

-0.12 |

| 1-Yr |

9.45 |

9.40 |

-0.05 |

| 2-Yr |

9.60 |

9.55 |

-0.05 |

| 3-Yr |

9.65 |

9.63 |

-0.02 |

| 4-Yr |

9.65 |

9.68 |

0.03 |

| 5-Yr |

9.70 |

9.70 |

0.00 |

| 6-Yr |

9.73 |

9.73 |

0.00 |

| 7-Yr |

9.73 |

9.73 |

0.00 |

| 8-Yr |

9.73 |

9.73 |

0.00 |

| 9-Yr |

9.73 |

9.73 |

0.00 |

| 10-Yr |

9.73 |

9.73 |

0.00 |

| Up to 3-yrs |

9.38 |

9.29 |

-0.09 |

| Median Base Rate |

| |

9.65 |

9.65 |

0.00 |

| Variation (MCLR over Base Rate) (Percentage Points) |

| As on |

Overnight |

1-Yr |

Up to 3-Yrs |

| April 04, 2016 |

-0.60 |

-0.20 |

-0.27 |

| July 31, 2016 |

-0.70 |

-0.25 |

-0.36 |

III.15 In a competitive environment, it is expected

that the return on net worth of banks would vary in

a narrow range. Data for the month of June 2016,

however, show wide variations in the expected

return on net worth – between 0.33 per cent and

26.44 per cent (Table III.5).

Agenda for 2016-17

III.16 In the first bi-monthly policy statement for

2016-17, the Reserve Bank set a target for CPI

inflation at 5 per cent by March 2017. The eventual

aim is to move towards 4 per cent CPI inflation by

the end of 2017-18.

III.17 To strengthen the monetary policy

framework, the Union Budget 2016-17 announced

the formal constitution of a Monetary Policy

Committee (MPC) by amending the RBI Act, 1934,

which will be vested with the responsibility of setting the policy rate. With the introduction of MPC, the

decision making process will imbue diversity of

views, specialised experience and independence

of opinion, which will bring transparency to the

overall decision-making process. In this context,

as the cross-country experience shows, there is

an increasing recognition of the merit in following

a collegial approach to monetary policy decision

making, irrespective of whether the countries are

following inflation targeting or not (Box III.2).

| Table III.5: Return on Net Worth Expected by

Banks - June 2016 |

| (Per cent) |

| Bank Group |

Min |

Max |

Median |

| Public Sector Banks |

2.00 |

25.00 |

16.00 |

| Private Sector Banks |

2.81 |

22.00 |

16.50 |

| Old |

2.81 |

22.00 |

15.25 |

| New |

6.25 |

20.00 |

18.00 |

| Foreign Banks |

0.33 |

26.44 |

10.00 |

| SCBs |

0.33 |

26.44 |

14.00 |

III.18 The amended RBI Act, which was notified

in the Gazette of India on May 14, 2016 mandates

a Monetary Policy Committee to determine the

policy interest rate to achieve the inflation target

set by the Government. MPC is a new institutional

structure. The MPC shall consist of the Governor of

the Reserve Bank, the Deputy Governor-in-charge

of monetary policy, one officer of the Bank to be

nominated by the Central Board of the Reserve

Bank and three members to be appointed by the

Central Government. Each member shall have one

vote, and in the event of a tie, the Governor can

exercise a casting or second vote. The institution

of the MPC is the culmination of several preceding

processes and draws on the recommendations

of technical committees including the Committee

on Fuller Capital Account Convertibility, 2006

(Chairman: Shri S.S. Tarapore); the Committee on

Financial Sector Reforms, 2009 (Chairman: Dr.

Raghuram G. Rajan); the Committee on Financial

Sector Assessment, 2009 (Chairman: Dr. Rakesh

Mohan); the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms

Commission (FSLRC), 2013 (Chairman: Shri B.N.

Srikrishna) and the Expert Committee to Revise

and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework,

2014 (Chairman: Dr. Urjit R. Patel). It also

represents a progressive graduation of the initial

efforts towards collegial decision making under

the aegis of the Technical Advisory Committee on

Monetary Policy. The learning experience gained by the Reserve Bank will help refine and entrench

decision making under MPC with the passage of

time.

Box III.2

Committee Approach to Monetary Policy: International Experience

A committee approach to monetary policy decisions has

emerged as the preferred framework across the globe.

Several advantages have been cited for this: enabling a

confluence of specialised knowledge and expertise on the

subject domain; bringing together different stakeholders

and diverse opinion and improving representativeness; and

collective wisdom making the whole greater than the sum

of the parts (Blinder and Morgan, 2005 and Maier, 2010).

Even for countries like Canada, Israel and New Zealand

where the Governor is responsible for decision making de

jure, she/he is typically supported by an advisory committee

de facto. Within this committee approach, there are several

variants in terms of size and composition of the committee,

representation of the government, the manner in which

the members are appointed, the frequency of committee

meetings and how a decision is arrived at, i.e., by voting

or consensus, and whether there are external members or

not and if so full time or part time, all of which impact policy

outcomes (Table 1).

References:

Blinder A. and J. Morgan (2005), ‘Are Two Heads Better than

One? An Experimental Analysis of Group versus Individual

Decision-making’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 35(5).

Maier, P. (2010), ‘How Central Banks Take Decisions: An

Analysis of Monetary Policy Meetings’ in P.L. Siklos, M.T.

Bohl and M.E. Woher (eds), Challenges in Central Banking:

The Current Institutional Environment and Forces Affecting

Monetary Policy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

| Table 1: Structure of MPC in Select Countries |

| Country |

Started |

Internal

Members |

External

Members |

Government

Representa-

tive (s) |

External

Members |

Decision

Making |

| Full time/part time |

Voting |

Consensus |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

| Australia |

1959 |

3 |

6 |

Yes |

Part time |

✓ |

|

| Brazil |

1996 |

8 |

0 |

No |

NA |

|

✓ |

| Chile |

1990 |

5 |

0 |

No |

NA |

✓ |

|

| Czech Republic |

1998 |

7 |

0 |

No |

NA |

✓ |

|

| ECB |

– |

6 |

19 |

No |

Full time* |

|

✓ |

| Hungary |

1993 |

4-6 |

1-3 |

No |

Full time |

✓ |

|

| Indonesia |

2005 |

6 |

0 |

No |

NA |

|

✓ |

| Japan |

1998 |

3 |

6 |

Yes – no

voting rights |

Full time |

✓ |

|

| Mexico |

1994 |

5 |

0 |

No |

NA |

✓ |

|

| Norway |

2001 |

2 |

5 |

No |

Part time |

✓ |

|

| Poland |

1998 |

1 |

9 |

No |

Full time |

✓ |

|

| South Africa |

1999 |

8 |

0 |

No |

NA |

✓ |

|

| South Korea |

1997 |

2 |

5 |

No |

Full time |

✓ |

|

| Sweden |

1999 |

6 |

0 |

No |

NA |

✓ |

|

| Thailand |

2001 |

3 |

4 |

No |

Full time |

|

✓ |

| Turkey |

2001 |

6 |

1 |

Yes – no

voting rights |

Full time |

|

✓ |

| UK |

1997 |

5 |

4 |

Yes – no

voting rights |

Part time |

✓ |

|

| US |

1935 |

12 |

0 |

No |

NA |

✓ |

|

NA: Not applicable.

*: External members are governors of member central banks.

Sources: Central bank websites and CCBS Handbook No. 29, February 2012. |

III.19 The revised liquidity management

framework being implemented since April 2016 is

expected to smoothen the supply of durable liquidity

over the year and progressively lower the average

ex ante liquidity deficit in the system to a position

closer to neutrality. This warrants continuous

monitoring and preparedness to calibrate instruments to unforeseen liquidity developments

in pursuit of this objective. In particular, the risk

of easy liquidity conditions either driving WACR

below the repo rate or the associated lower term

repo auction volumes dampening the prospect of

development of a term money market will have

to be avoided. The Reserve Bank will objectively

assess the efficacy of MCLR vis-à-vis the earlier

base rate system in terms of monetary policy

transmission. |