Fundamental institutional changes impacted monetary policy in India following the amendment to

the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934, effected on June 27, 2016. The policy rate was reduced by

50 bps during 2016-17 and the policy stance shifted from accommodative to neutral in February 2017.

Even as inflation undershot the target of 5 per cent set for Q4 of 2016-17, monetary policy operations had to

contend with massive surplus liquidity conditions, necessitating a mix of conventional and unconventional

instruments of liquidity management. In spite of faster transmission of policy rate changes to marginal

cost of funds based lending rates (MCLRs), pass-through to actual lending rates remained incomplete.

III.1 The conduct of monetary policy in India

underwent a fundamental institutional reform

during the year 2016-17 in an environment fraught

with several challenges. Bouts of turbulence

ricocheting through global financial markets,

volatility in global crude oil prices, risk-laden

political climate globally, a distinctive break in

inflation formation in the domestic economy,

demonetisation and its side-effects, and new

data releases that overtook perceptions of the

state of the economy – all of these developments

impacted the setting of monetary policy with

different degrees of intensity and duration. In

this unsettled milieu, the agenda set for the

year was accomplished. The inflation target of 5

per cent for Q4 of 2016-17 was achieved with a

sizable undershoot as in the preceding two years

underscoring how extraordinary and intense ‘tail’

events, especially the food price dynamics, have

overwhelmed the trajectory of inflation in India.

The agenda for 2017-18 will be guided by the

mandate as enshrined in the RBI Act, 1934 “to

maintain price stability, while keeping in mind the

objective of growth’’. The materialisation of the path of monetary policy’s goal variable, viz., headline

consumer price inflation at 4.0 per cent with a ± 2

per cent tolerance band, and how it relates to the

conditional policy forecasts in numerical terms is

the recurring theme of the narrative of this chapter.

Even as inflation outcomes were falling off cliffs

during the year, the monetary policy framework

was undergoing a regime shift.

III.2 Parliament amended the RBI Act to accord

primacy to inflation as the goal of monetary policy

in India, while keeping in mind the objective of

growth. Subsequent notification in the Gazette

of India defined the goal. A Monetary Policy

Committee (MPC) was constituted and enjoined

to make the monetary policy decision under

explicitly laid out process of transparency and

accountability. The amended Act also required

the Reserve Bank to set out in the public domain

the operating procedure of monetary policy and

changes therein from time to time that would

secure the goals of monetary policy.

III.3 In accordance, a revised liquidity

management framework was implemented in April 2016 and published in the Monetary Policy

Report (MPR), which became a statutory bi-annual

requirement under the amended Act.

The operating framework of monetary policy was

further fine-tuned to enhance its effectiveness to

achieve the medium-term target of 4 per cent –

the centre of the target band – on a continuous

basis. Operations under this framework are

examined in the sub-section on The Operating

Framework: Liquidity Management especially in

the context of the exceptional swings in liquidity

that have characterised the year gone by. Issues

in the transmission of monetary policy impulses to

actual lending rates in the economy, particularly

those lost to structural impediments (Box III.1)

are addressed in sub-section on Monetary

Policy Transmission. Finally, the chapter sets out

an agenda that will guide the formulation and

implementation of monetary policy in 2017-18 in

pursuit of the mandate of price stability, keeping in

mind the objective of growth.

Agenda for 2016-17: Implementation Status

Monetary Policy

III.4 The first bi-monthly monetary policy

statement for 2016-17 issued in April was

formulated to subserve an accommodative

policy stance. The key policy repo rate was cut

by 25 bps to 6.5 per cent, its lowest since March

2011. Given the weak state of domestic demand

relative to potential, the policy rate reduction was

expected to help in reviving investment activity.

By the time of the second bi-monthly monetary

policy statement in June 2016, inflation readings

showed a sharper-than-anticipated upsurge,

driven primarily by food prices, interrupting the

phase of policy rate reductions signalled in April.

Accordingly, the policy rate was left unchanged

while persevering with an accommodative stance,

as further clarity from incoming data was awaited

on the evolving inflation trajectory.

III.5 Amendments to the RBI Act, which came

into force on June 27, 2016, provided the legislative

mandate to the Reserve Bank to operate the

monetary policy framework of the country with the

primary objective explicitly defined to “maintain

price stability while keeping in mind the objective

of growth”. While the monetary policy objective of

price stability has been explicitly specified in terms

of the commitment to meet the inflation target

based on the headline Consumer Price Index

(CPI), the factors that constitute a failure to achieve

the inflation target, i.e., if the average inflation is

more (less) than the upper (lower) tolerance level

for three consecutive quarters, have also been

defined and notified in the official Gazette. To

operationalise this mandate, the Government, on

August 5, 2016, notified the inflation target as four

per cent year-on-year growth in CPI-Combined

inflation, with upper and lower tolerance levels of

six per cent and two per cent, respectively.

III.6 The amended RBI Act also provided for

the constitution of a six member MPC. As per the

amended RBI Act, the MPC would be entrusted

with the task of fixing the benchmark policy rate

(repo rate) required to contain inflation within the

specified target level. Out of the six members of the

MPC, three members would be from the Reserve

Bank and the other three members would be

appointed by the central government. The three

external members would hold office for a period of

four years. The MPC is stipulated to hold meetings

at least four times a year. To ensure transparency

of the MPC proceedings, the amended RBI Act

prescribes for attributing the vote of each member

of the MPC. It also requires each member of the

MPC to write a statement specifying the reasons

for voting in favour of, or against the proposed

resolution. At the end of each meeting, the MPC

would publish the resolution adopted by the Committee. On the fourteenth day after every

meeting of the MPC, the minutes of the meeting

containing the resolution adopted at the meeting

of the MPC, the vote of each member of the MPC

ascribed to such member, and the statement of

each member of the MPC are required to be put out

in the public domain. In the case of failure to meet

the target, wherein the average inflation remains

more (less) than the upper (lower) tolerance level

of the inflation target for any three consecutive

quarters, the Reserve Bank would have to explain

in a report to the central government setting out

the reasons for failure to achieve the inflation

target; the remedial actions proposed to be taken

by the Reserve Bank; and an estimate of the time

period within which the inflation target would be

achieved.

III.7 The amended RBI Act also requires the

publication of MPR, once in every six months,

explaining the sources of inflation; and the

forecasts of inflation for the period between six

to eighteen months from the date of publication

of the document. The Reserve Bank has been

publishing the MPR since September 2014.

III.8 The third bi-monthly monetary policy

statement of August 2016 kept the policy repo rate

unchanged, assessing that risks to the inflation

target of 5 per cent for March 2017 still remained on

the upside, given the implications of the 7th Central

Pay Commission’s (CPC’s) award on inflation

trajectory and inflation expectations. Further,

uncertainty on trajectory of inflation excluding

food and fuel arose from the possibility of higher

input price pressures and whether the then benign

movement in crude prices would turn out to be

transient, feeding to output prices as output gap

continued to close. An upturn in inflation excluding

food and fuel on account of these factors, possibly

even counterbalancing the benefit of the expected easing of food inflation, was also highlighted by

the policy statement. However, the monetary

policy stance continued to be accommodative with

emphasis on pro-active liquidity management to

enable faster pass-through of the past policy rate

cuts to the banks’ MCLRs.

III.9 Under the new framework, the six-member

MPC constituted on September 29, 2016 met for

the first time on October 3 and 4, 2016 in the

context of the fourth bi-monthly monetary policy

statement. Observing that space had opened

up by the moderating trajectory of inflation,

underpinned by the supply side measures taken

by the Government, the MPC unanimously voted

for a reduction in the key policy rate by 25 bps. The

steady improvement in liquidity conditions from

deficit at the beginning of the year to surplus by July

2016, under the modified liquidity management

framework, helped transmit the policy rate

reduction to various segments of the market. The

MPC assessed that inflation would remain within 5

per cent by Q4 of 2016-17, though potential cost-push

pressures, including the impending 7th CPC’s

award on house rent allowances, and the increase

in minimum wages with potential spillovers to

minimum support prices, were flagged as upside

risks to inflation.

III.10 The MPC’s meeting of December 6 and

7, 2016 for the fifth bi-monthly monetary policy

statement was overcast by heightened uncertainty

around the outlook for growth and inflation in the

aftermath of demonetisation. In the MPC’s view,

short-run disruptions in economic activity in cash-intensive

sectors were likely to be transitory,

given the war-time drive launched by the Reserve

Bank to restore the pre-demonetisation stock

of currency in circulation by ramping up the

circulation of new currency notes, alongside

the greater usage of non-cash based payment instruments in the economy. The large surplus

liquidity following the demonetisation in November

2016, was also considered transitory in view

of liquidity management operations targeted at

restoring system-level liquidity to a position closer

to neutrality. Accordingly, the MPC unanimously

decided to keep policy repo rate unchanged, while

continuing with an accommodative policy stance.

III.11 In the sixth bi-monthly monetary policy

statement of February 8, 2017, the MPC judged

that growth would recover sharply in 2017-18 on

account of the following factors: (i) a resurgence

of discretionary consumer demand, held back

by demonetisation; (ii) quick revival of economic

activity in cash-intensive sectors; (iii) pick-up

in both consumption and investment demand

as the demonetisation-induced ease in bank

funding conditions leads to a sharp improvement

in transmission of past policy rate reductions into

MCLRs, and in turn, to lending rates for healthy

borrowers; and (iv) the positive impact on growth

of measures announced in the Union Budget for

2017-18 to step up capital expenditure, boost

the rural economy and affordable housing. The

MPC reiterated its commitment to bring headline

inflation closer to 4.0 per cent on a durable basis

and in a calibrated manner, noting that this required

further significant decline in inflation expectations.

While observing that the persistence of inflation

excluding food and fuel could set a floor on further

downward movements in headline inflation and

trigger second-order effects, the MPC indicated

that it needed more time to assess the manner in

which the transitory effects of demonetisation on

inflation and the output gap could play out. The

committee decided to change the policy stance

from accommodative to neutral while keeping the

policy rate on hold.

III.12 The headline inflation target of 5.0 per

cent for Q4 of 2016-17 undershot by around 140 bps largely driven by deflation in pulses and

vegetables. The sustained decline in food prices

since August 2016 has been unprecedented by

historical patterns. The initial drop in food prices

was driven by correction in prices of pulses and

vegetables in response to supply management

measures. Since November, collapse in vegetable

prices across the board was driven by demand

compression and fire sales of vegetables post

demonetisation in a scenario of high seasonal

supply. While the sharp decline in vegetable

prices was expected to be transitory as effects

of demonetisation fade, there was considerable

uncertainty on the timing and the strength of the

expected reversal, especially during the summer

months. Pulses were expected to remain soft on

the back of a sharp rise in production and imports.

III.13 In the first bi-monthly monetary policy

statement for 2017-18 of April 6, 2017, the MPC

held the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.25

per cent while persevering with a neutral policy

stance. The statement observed that although

CPI headline inflation fell to the then historic low

in January 2017 due to sharp moderation in food

inflation, inflation excluding food and fuel had

remained relatively sticky since September 2016

and was significantly above the headline inflation.

Though inflation was projected to be moderate

in the first half of the year, significant upside risks

remained in the form of uncertainty of monsoon,

implementation of allowances under the 7th CPC

even as moderation in crude prices and softening

of food prices could help contain inflation

impulses. Growth was projected to strengthen

to 7.4 per cent in 2017-18 from 6.7 per cent in

2016-17. As the output gap could gradually close,

aggregate demand pressures would build up, with

implications for the inflation trajectory, which was

projected to move up in the second half of the year. In this context, the MPC noted that the future

course of monetary policy would largely depend

on incoming data and evolving macroeconomic

conditions and underlined the need to closely and

continuously monitor inflation developments.

III.14 The second bi-monthly monetary policy

statement for 2017-18 of June 7, 2017 was

overshadowed by inflation falling below 4.0 per

cent in May 2017. While reiterating its commitment

to keep headline inflation close to 4.0 per cent on

a durable basis, the MPC took cognizance of the

unusual softening of headline inflation on account

of the sharp moderation in food inflation. inflation

projections were revised downwards to a range of

2.0-3.5 per cent in the first half of the year and

3.5-4.5 per cent in the second half of 2017-18. The

Committee noted that the risk of fiscal slippages,

which, by and large, could entail inflationary

spillovers, had risen with the announcements

of large farm loan waivers. This along with the

global, political and financial risks materialising

into imported inflation and the disbursement of

allowances under the 7th CPC’s award would be

the upside risks. Given, however, the uncertainty

surrounding the evolving inflation trajectory,

especially for the near months, the MPC was of the

view that premature monetary policy responses

risk disruptive policy reversals later and the loss

of credibility. The MPC’s resolution underlined

the need to revive private investment, restore

banking sector health and remove infrastructural

bottlenecks for monetary policy to play an effective

role. Accordingly, the MPC decided to keep the

policy repo rate unchanged at 6.25 per cent with

a neutral stance while remaining watchful of the

incoming data.

The Operating Framework: Liquidity Management

III.15 The operating framework of monetary

policy aims at aligning the operating target – the weighted average call rate (WACR) – with the policy

repo rate through proactive liquidity management

consistent with the stance of monetary policy.

Liquidity management during 2016-17 can

be heuristically categorised into two distinct

phases. First, active operations were launched to

progressively move the ex-ante liquidity position

in the system from deficit to closer to neutrality.

Second, managing the post-demonetisation surge

in surplus liquidity became an overriding priority,

warranting unorthodox instruments to augment

the arsenal of regular operations so as to prevent

excessive softening of money market rates under

the weight of the deluge of liquidity.

III.16 The liquidity management framework

was modified in April 2016 in the first phase. The

Reserve Bank proactively injected durable liquidity

of ₹2.1 trillion during the year up to November 8,

2016 (i.e., the pre-demonetisation period) in the

form of open market purchase operations, net forex

market operations, and buyback of government

securities. As a result, the system level ex-ante

liquidity position transited from a deficit of about

₹813 billion, on a daily average basis, in Q1 to a

surplus of ₹292 billion in Q2 and ₹64 billion in Q3

(up to November 8, 2016).

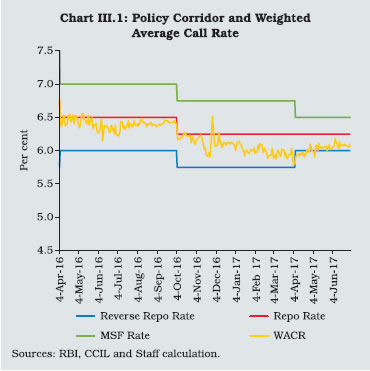

III.17 Two other changes under the modified

liquidity management framework worked in

combination to tightly anchor money market rates

with the policy rate. First, the cash reserve ratio

(CRR) maintenance requirement was reduced

to a daily minimum of 90 per cent from 95 per

cent earlier, which moderated banks’ holdings of

excess reserves. Second, the policy rate corridor

was narrowed to +/-50 bps on April 5, 2016, on the

back of assurance of both durable and frictional

liquidity. This narrowed the spread of WACR vis-à-vis

the repo rate and reduced its volatility (Charts

III.1 and III.2). The Reserve Bank also ensured front-loading of adequate liquidity proactively

in anticipation of potential pressure and market

concerns arising out of scheduled redemptions of

foreign currency non-resident (bank) [FCNR (B)]

deposits. As a result, liquidity turned into surplus

even prior to the announcement of demonetisation

on November 8, 2016.

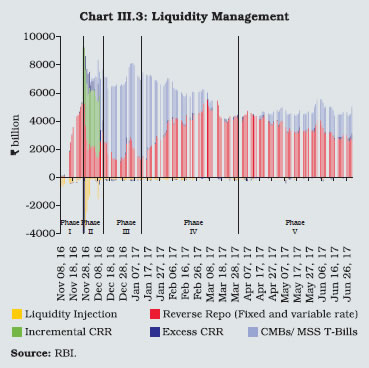

III.18 With regard to the unprecedented surge

of surplus liquidity created by demonetisation, a

mix of instruments was employed by the Reserve

Bank at different points in time (Chart III.3).

Each instrument has distinct advantages and

disadvantages (Table III.1).

III.19 After demonetisation, currency in circulation

declined by about ₹8,997 billion (up to January 6,

2017), which resulted in a large increase in surplus

liquidity with the banking system, equivalent to a

cut in the CRR by about 9 per cent. This, in turn,

posed a formidable challenge to the Reserve

Bank’s liquidity management operations. Initially,

conventional instruments, especially reverse

repo auctions under the liquidity adjustment

facility (LAF) window, were deployed to absorb surplus liquidity. Recognising, however, that these

operations could potentially be constrained by the

finite stock of domestic securities available with

the Reserve Bank, a pre-emptive strategy was put

in place involving two unconventional measures.

III.20 First, an incremental cash reserve ratio

(ICRR) of 100 per cent on the increase in net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) of banks

between September 16 and November 11,

2016 was applied. Second, the Government

was requested to enhance the limit of securities

issuable under the market stabilisation scheme

(MSS) to ₹6,000 billion from ₹300 billion. Open

market sales of cash management bills (CMBs)

issued under the MSS were undertaken (from

December 2, 2016 to January 13, 2017), which

marked a departure from the original intent of the

MSS of dealing with liquidity arising from surges in capital flows. The ICRR was withdrawn after

the Reserve Bank’s capacity to auction securities

expanded under the enhanced MSS limit.

| Table III.1: Advantages and Disadvantages of Instruments for Absorbing Surplus Liquidity |

| Instruments |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Incremental cash reserve ratio |

Most effective in absorbing any amount of

surplus liquidity without being constrained by

collateral. |

Unremunerated and therefore a cost to

the banking system; not a market based

instrument. |

| Securities issued under the MSS |

This is a market based instrument and

suitable for absorbing liquidity for a longer

period relative to reverse repos under

the LAF. Market participants prefer this

instrument vis-à-vis reverse repo because of

liquidity of the underlying instrument. |

Requires timely consent of the Government

of India.

Can bid up yields due to repetitive auctions. |

| Open market (outright) operations – sales |

Key market based indirect instrument for

absorbing durable surplus liquidity; most

effective indirect instrument. |

Requires adequate stock of domestic

securities in the portfolio of the Reserve

Bank; large scale operations can potentially

influence yields that may not be consistent

with the stance of monetary policy. |

| Term reverse repo auctions |

Provide flexibility in terms of responding to

fast changing liquidity conditions on a daily

basis; rollover option; simultaneous auctions

of multiple tenor; can aid the development of

the term money market. |

Inadequate market appetite for longer-term

auctions; may not prevent significant easing

of WACR under persistently high surplus

liquidity conditions; domestic securities

available with the Reserve Bank can limit the

use of term reverse repo. |

| Fine tuning overnight reverse repo auctions |

Robust market appetite because of the ease

of rollover; ideal instrument for managing

frictional surplus liquidity. |

Not suitable for dealing with large durable

surplus; most effective not in isolation

but when used in conjunction with other

instruments. |

| Fixed rate reverse repo window (the floor of

the LAF corridor) |

Provides certainty to market participants

about the surplus liquidity to be parked

overnight at a rate that is known in advance.

As there is no limit on the amount that could

be parked, it prevents WACR falling below

the lower bound of the corridor. |

Extensive use can lead to excessive easing

of the WACR relative to the repo rate within

the LAF corridor; domestic securities

available with the Reserve Bank can limit

the amount of absorption; can lead to ‘lazy’

liquidity management by banks and thus

effectively shift the money market on to the

Reserve Bank’s balance sheet. |

III.21 With fast paced remonetisation, surplus

liquidity in the system declined by mid-January

2017. As a result, the Reserve Bank reverted to its

conventional instruments – reverse repo auctions

– and discontinued further issuances of MSS

securities from January 14, 2017. All outstanding

MSS securities matured by end-March 2017.

III.22 The post-demonetisation period has had

five different phases of liquidity management

(Chart III.3).

III.23 In the first phase (November 10 to

November 25, 2016), the Reserve Bank

extensively used variable rate reverse repos of

tenors ranging from overnight up to 91 days. The

outstanding amount of surplus liquidity absorbed

through reverse repos (both variable rate and

fixed rate auctions) reached a peak of ₹5,242

billion on November 25.

III.24 In the second phase (November 26 to

December 9, 2016), 100 per cent ICRR was

applied, which helped drain excess liquidity in the

system to the extent of about ₹4,000 billion.

III.25 In the third phase (December 10, 2016

to January 13, 2017), the surplus liquidity was

managed through a mix of reverse repos and

issuances of CMBs under the MSS, with a

gradually increased reliance on the latter. The

peak net outstanding liquidity absorbed was

₹7,956 billion on January 4, 2017 (₹2,568 billion

absorbed through reverse repos and ₹5,466 billion

through CMBs).

III.26 In the fourth phase (January 14 to end-

March 2017), the Reserve Bank returned to the

conventional reverse repo operations as the key

instrument to absorb surplus liquidity, particularly

the liquidity released through the maturing CMBs

under the MSS.

III.27 The usual year-end liquidity pressure

stemming from banks’ balance sheet adjustments

and tax payments to the government did not lead

to a very sharp spike in money market rates this

time around due to the large post-demonetisation

liquidity overhang. The absorption of liquidity

surplus using reverse repos (at both fixed and

variable rates) peaked at ₹5,522 billion on March

6, 2017. The surplus liquidity conditions continued in March, but net absorption of liquidity under

the LAF declined to ₹3,141 billion by end-March,

reflecting the build-up of cash balances by the

Government and higher excess CRR maintained

by banks.

III.28 In the fifth phase that began in April 2017

with the first auction of Treasury Bills (T-Bills)

under the MSS, surplus liquidity was managed

with a mix of issuance of T-Bills under the MSS

and reverse repo auctions. Anticipating that the

surplus liquidity conditions may persist through

2017-18, in April 2017 the Reserve Bank provided

guidance on liquidity, which contained the following

elements: (i) use of T- Bills and dated securities

under the MSS up to ₹1 trillion; (ii) issuances of

CMBs of appropriate tenors in accordance with

the memorandum of understanding (MoU) with

the Government of India to manage enduring

surpluses due to government operations up to

₹1 trillion; (iii) open market operations with a view

to moving system level liquidity to neutrality; and

(iv) fine tuning reverse repo/repo operations to

modulate day to day liquidity. The Reserve Bank

auctioned T-Bills (tenors ranging from 312 days to

329 days) aggregating ₹1 trillion in April and May

2017.

III.29 The WACR – the operating target of

monetary policy – traded at only about 15

basis points (bps) below the repo rate between

November 9, 2016 and January 13, 2017 and

about 27 bps below the repo rate on daily average

basis between January 14 and March 31, 2017.

While the WACR remained within the LAF

corridor, the large deviation of the WACR from the

policy repo rate during Q4 was mainly on account

of exclusive reliance on reverse repos to absorb

surplus liquidity arising out of maturing CMBs

(Chart III.4). After narrowing of the LAF corridor to

+/- 25 bps on April 6, 2017, the average spread of

WACR below the repo rate declined to 17 bps in June as compared with 31 bps and 21 bps in April

and May, respectively.

Monetary Policy Transmission

III.30 The Reserve Bank reduced the policy

repo rate by a cumulative 175 bps during January

2015 to June 2017. In response, banks reduced

their weighted average domestic term deposit

rate (WADTDR) by 126 bps during January

2015 to October 2016. The weighted average

lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee loans and

outstanding rupee loans declined by 97 bps and

75 bps, respectively, during the same period. The

reduction in the WADTDR was significantly higher

than that in the lending rates (Table III.2).

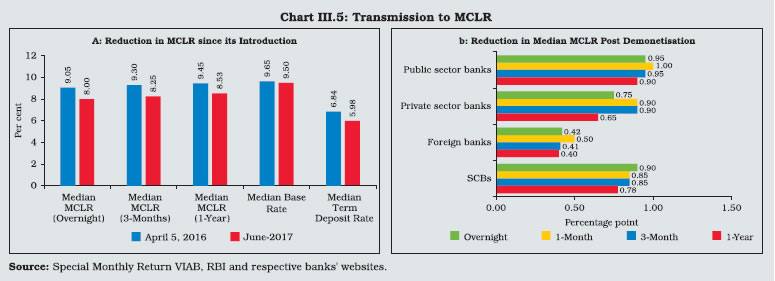

III.31 Monetary transmission, however, improved

significantly post-demonetisation. Buoyed by the

surplus liquidity, the share of current account and

saving account (CASA) deposits in aggregate

deposits increased to 40.6 per cent as at end-March 2017 from 35.2 per cent at end-October

2016, before declining to 38.6 per cent on June 23,

2017 (Table III.3). As the cost of CASA deposits

(3.2 per cent) is significantly lower than the

WADTDR, the overall cost of borrowings declined,

enabling banks to cut their lending rates. Banks

also lowered their median term deposit rate by 56

bps during November 2016 to June 2017. As a

result, the WALR on fresh rupee loans declined

by 98 bps, while the WALR on outstanding rupee

loans declined by 42 bps (up to June 2017).

| Table III.2: Deposit and Lending Rates of SCBs (Excluding RRBs) |

| (Per cent) |

| End-Month |

Repo Rate |

Term Deposit Rates |

Lending Rates |

| Median Term

Deposit Rate |

WADTDR |

Median Base

Rate |

WALR -

Outstanding

Rupee Loans |

WALR - Fresh

Rupee Loans |

MCLR

1- Yr Median |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

| Dec-2014 |

8.00 |

7.53 |

8.64 |

10.25 |

11.84 |

11.45 |

- |

| Mar-2015 |

7.50 |

7.49 |

8.57 |

10.20 |

11.76 |

11.07 |

- |

| Mar-2016 |

6.75 |

6.81 |

7.73 |

9.65 |

11.20 |

10.47 |

- |

| Apr-2016 |

6.50 |

6.65 |

7.64 |

9.65 |

11.23 |

10.59 |

9.45 |

| June-2016 |

6.50 |

6.63 |

7.59 |

9.65 |

11.19 |

10.43 |

9.45 |

| Sep-2016 |

6.50 |

6.52 |

7.41 |

9.65 |

11.13 |

10.35 |

9.35 |

| Oct-2016 |

6.25 |

6.54 |

7.38 |

9.64 |

11.09 |

10.48 |

9.30 |

| Dec-2016 |

6.25 |

6.22 |

7.19 |

9.64 |

11.07 |

10.12 |

9.15 |

| Mar-2017 |

6.25 |

6.15 |

6.97 |

9.55 |

10.80 |

9.74 |

8.60 |

| May-2017 |

6.25 |

6.08 |

6.86 |

9.50 |

10.66 |

9.84 |

8.55 |

| June-2017 |

6.25 |

5.98 |

6.81 |

9.50 |

10.67 |

9.50 |

8.53 |

| Variation (Percentage Points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Oct-16 over Dec-14 |

-1.75 |

-0.99 |

-1.26 |

-0.61 |

-0.75 |

-0.97 |

- |

| Oct-16 over Mar-16* |

-0.50 |

-0.27 |

-0.35 |

-0.01 |

-0.11 |

0.01 |

-0.15 |

| Jun-2017 over Oct-16 |

0.00 |

-0.56 |

-0.57 |

-0.14 |

-0.42 |

-0.98 |

-0.77 |

WADTDR: Weighted Average Domestic Term Deposit Rate. WALR: Weighted Average Lending Rate.

MCLR was introduced on April 1, 2016.

*: For MCLR, the period pertains to October 2016 over April 2016.

Source: Special Monthly Return VIAB, RBI and banks’ websites. |

| Table III.3: Share of CASA Deposits in Aggregate Deposits |

| (Amount in ₹ billion) |

| Fortnight ended |

Demand Deposits@ |

Time Deposits@ |

Saving Deposits |

Aggregate Deposits |

Share of CASA Deposits (in per cent) |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| 18-Mar-16 |

6,874 |

59,530 |

23,930 |

90,333 |

34.1 |

| 28-Oct-16 |

7,175 |

62,295 |

26,673 |

96,143 |

35.2 |

| 31-Mar-17 |

10,135 |

61,774 |

32,022 |

1,03,931 |

40.6 |

| 23-Jun-17 |

8,356 |

62,586 |

31,034 |

1,01,976 |

38.6 |

@: Net of liabilities from saving account.

Source: Section 42 Banking Data, RBI. |

III.32 It is significant that the one-year median

MCLR declined by a cumulative 77 bps from

November 2016 to June 2017 even when the policy

rate was unchanged. This is in sharp contrast to

the decline in the median one-year MCLR by just 15 bps during the preceding seven months when

the policy rate was cut by 50 bps. The largest

reduction in MCLR post-demonetisation was

effected by public sector banks, followed by private

sector banks and foreign banks (Chart III.5).

Sectoral Lending Rates

III.33 Transmission was asymmetric across

sectors, reflecting varied credit conditions and

risk appetite. Since January 2015, lending rates

across sectors, barring credit card segment,

declined in the range of 15-238 bps, with the

largest transmission taking place in the case of

Rupee export credit (Table III.4).

III.34 Interest rates on fresh rupee loans declined

significantly in respect of housing in personal loan segment and vehicle loans in the commercial

segment during January 2015 to June 2017

(Table III.5).

Table III.4: Sector-wise WALR of SCBs (Excluding RRBs) - Outstanding Rupee Loans

(at which 60 per cent or more business is contracted) |

| (Per cent) |

| End-Month |

Rupee Export Credit |

Trade |

Industry (Large) |

Profes- sional Services |

Infra- struc- ture |

Personal- Other@ |

Personal Education |

MSMEs |

Personal Housing |

Personal Vehicle |

Agricul-

ture |

Per- sonal Credit Card |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

| Dec-14 |

12.16 |

13.09 |

12.95 |

12.39 |

13.05 |

14.24 |

12.90 |

13.05 |

10.76 |

11.83 |

10.93 |

37.86 |

| Mar-15 |

12.04 |

13.07 |

12.80 |

12.46 |

12.89 |

13.94 |

12.87 |

12.91 |

10.99 |

11.62 |

10.96 |

37.88 |

| Mar-16 |

11.46 |

12.50 |

12.36 |

11.81 |

12.06 |

13.90 |

12.48 |

12.25 |

10.56 |

11.65 |

10.74 |

38.00 |

| Jun-16 |

11.17 |

11.99 |

12.17 |

11.64 |

12.20 |

13.96 |

12.32 |

12.08 |

10.50 |

11.39 |

10.77 |

38.26 |

| Sep-16 |

10.54 |

11.91 |

11.68 |

11.65 |

12.07 |

12.89 |

12.09 |

12.18 |

10.01 |

11.46 |

10.91 |

39.07 |

| Oct-16 |

10.78 |

11.86 |

11.64 |

11.56 |

11.89 |

12.98 |

12.40 |

12.23 |

10.00 |

11.45 |

10.88 |

39.01 |

| Dec-16 |

10.61 |

11.78 |

11.63 |

11.49 |

11.78 |

13.11 |

11.95 |

12.03 |

9.95 |

11.24 |

10.86 |

38.84 |

| Mar-17 |

10.98 |

11.59 |

11.57 |

11.21 |

11.80 |

12.85 |

11.70 |

11.88 |

9.78 |

11.05 |

10.95 |

39.02 |

| May-17 |

10.61 |

11.36 |

11.44 |

10.97 |

11.94 |

12.97 |

11.79 |

11.73 |

9.75 |

11.00 |

10.81 |

38.93 |

| Jun-17 |

9.78 |

11.41 |

11.28 |

10.91 |

11.59 |

12.85 |

11.53 |

11.75 |

9.59 |

10.87 |

10.78 |

38.88 |

| Variation (Percentage Points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jun-17 over Dec-14 |

-2.38 |

-1.68 |

-1.67 |

-1.48 |

-1.46 |

-1.39 |

-1.37 |

-1.30 |

-1.17 |

-0.96 |

-0.15 |

1.02 |

| Jun-17 over Oct-16 |

-1.00 |

-0.45 |

-0.36 |

-0.65 |

-0.39 |

-0.13 |

-0.87 |

-0.48 |

-0.41 |

-0.58 |

-0.10 |

-0.13 |

@: Other than housing, vehicle, education and credit card loans.

Source: Special Monthly Return VIAB, RBI. |

| Table III.5: WALR of Select Sectors of SCBs

(Excluding RRBs) - Fresh Rupee

Loans Sanctioned |

| (Per cent) |

| End-Month |

Personal |

Commercial |

| Housing |

Vehicle |

Housing |

Vehicle |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Dec-14 |

10.53 |

12.28 |

11.73 |

12.53 |

| Mar-15 |

10.47 |

12.42 |

12.04 |

12.30 |

| Mar-16 |

9.78 |

11.98 |

11.14 |

11.21 |

| Jun-16 |

9.64 |

11.79 |

10.53 |

11.49 |

| Sep-16 |

9.58 |

11.79 |

10.94 |

11.73 |

| Oct-16 |

9.55 |

11.50 |

10.70 |

11.79 |

| Dec-16 |

9.50 |

11.13 |

10.59 |

11.17 |

| Mar-17 |

8.94 |

10.77 |

10.03 |

10.24 |

| May-17 |

8.93 |

10.97 |

10.05 |

11.21 |

| Jun-17 |

8.99 |

10.81 |

10.42 |

10.83 |

| Variation (Percentage Points) |

|

|

|

| Jun-17 over Dec-14 |

-1.54 |

-1.47 |

-1.31 |

-1.70 |

| Jun-17 over Oct-16 |

-0.56 |

-0.69 |

-0.28 |

-0.96 |

| Source: Special Monthly Return VIAB, RBI. |

III.35 The pace of transmission to lending rates

was significantly slower than to deposit rates and

the MCLR on account of several factors. First,

banks treated the increase in CASA deposits as

transitory. The share of CASA deposits, which

had peaked in December 2016, declined with

progressive remonetisation; consequently, banks

were reluctant to adjust their lending rates fully.

Second, a sizeable share of past loans continues

to be priced with reference to the base rate. As

against a cumulative decline of 85 bps in the

1-year median MCLR during 2016-17, the median

base rate declined by only 10 bps over the same

period, resulting in a slower pace of transmission

to WALR on outstanding rupee loans. Third,

among the various components of the MCLR, only

the term deposit rates responded to the change in

the policy rate. Fourth, the higher lending spread

maintained by banks in the wake of stressed

asset quality of banks impeded transmission (Box III.1). Fifth, administered interest rates on

small savings have not moved adequately in line

with underlying changes in yields on government securities to which they are to be linked for

quarterly resetting. Going forward, greater liquidity

across various segments and maturity spectrum of financial markets, particularly, term money

and corporate bond markets, could facilitate

emergence of an external benchmark for pricing

of credit, contributing to speedier monetary policy

transmission.

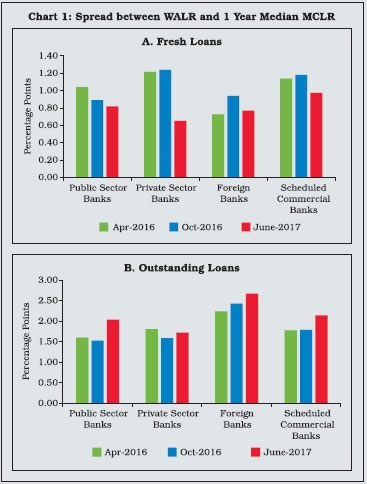

Box III.1

MCLR, Lending Rates and Health of the Banking Sector

The MCLR system, introduced in April 2016, was expected

to improve monetary policy transmission to banks’ lending

rates. Preliminary evidence suggests that while transmission

of the policy rate to MCLR has improved, the transmission

to lending rates has remained muted. This is because banks

often adjust the spread they charge over MCLR – both in

respect of the outstanding rupee loans and fresh rupee loans

sanctioned by banks (Chart 1). An inter-sectoral comparison

reveals that the spread between WALR and 1-year median

MCLR increased across most sectors during 2016-17

(Table 1). While some change in the spread is inevitable

due to sector-specific factors and the underlying risk, banks

appeared to have also changed spreads to improve their

net interest margins (NIMs), i.e., the difference between

interest income and interest expenditure, to compensate for

increased credit risk.

Regression analysis based on the data for the period

Q1:2010-11 to Q3:2016-17 suggests that an increase in stressed assets1 is associated with higher NIMs (Raj, et

al, 2017)2. The foreign banks that experienced increase in

stressed assets from relatively lower levels were also able

to increase their NIMs. The coefficient of stressed assets

in respect of public and private sector banks is positive but

statistically insignificant (Table 2).

| Table 1: Spread between WALR and 1-Year Median MCLR |

| (Basis Points) |

| Sector |

Apr-16 |

Mar-17 |

Jun-17 |

| Agriculture |

128 |

235 |

225 |

| Industry (Large) |

287 |

297 |

275 |

| MSMEs |

284 |

328 |

322 |

| Infrastructure |

281 |

320 |

306 |

| Trade |

307 |

299 |

288 |

| Professional Services |

230 |

261 |

238 |

| Personal Housing |

110 |

118 |

106 |

| Personal Vehicle |

220 |

245 |

234 |

| Education |

297 |

310 |

300 |

| Credit Card |

2891 |

3042 |

3035 |

| Rupee Export Credit |

180 |

238 |

125 |

| Source: Special Monthly Return VIAB, RBI. |

| Table 2: Determinants of Net Interest Margin |

| Variables |

Public Sector Banks |

Private Sector Banks |

Foreign Banks |

SCBs |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| NIM(-1) |

0.785* |

0.650* |

0.521* |

0.568* |

| Stressed Assets |

0.002 |

0.005 |

0.023* |

0.008* |

| CRAR |

-0.005 |

0.003 |

0.002** |

0.003* |

| Credit Growth |

0.000 |

-0.001 |

0.0003** |

0.0002** |

| Operating Expense |

0.213* |

0.296* |

0.128** |

0.162* |

*: Significant at 1 per cent level; **: Significant at 5 per cent level.

Notes:

Model Specification: Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond dynamic panel-data regression-System GMM with bank fixed effects.

NIM = (Interest income minus interest expense) to total assets (in per cent).

Stressed assets = (Restructured assets plus gross NPAs) to total assets (in per cent).

The regressions are controlled for seasonality, credit growth, bank size, capital adequacy, return on assets, operating expense, non-interest income,

investment in SLR securities, GVA growth and inflation.

Hansen test for over identification restrictions and Arellano-Bond test for residual auto correlations are found to be satisfactory.

Source: Supervisory Returns, RBI. |

Reference:

Raj, Janak, D.P. Rath, A. K. Mitra and J. John (2017), “Banks’ Health and Monetary Transmission”, Reserve Bank of India, mimeo. |

Agenda for 2017-18

III.36 The agenda for 2017-18 will be guided by

the mandate as enshrined in the RBI Act, 1934 “to

maintain price stability, while keeping in mind the

objective of growth’’. The key agenda for 2017-18,

therefore, will focus on studying those aspects,

which may have a significant bearing on inflation

projections going forward. This will include: (i)

examining the impact of implementation of the

7th CPC’s award on inflation; (ii) assessing the

impact of GST on inflation; (iii) analysing the

impact of farm loan waivers on the fiscal situation

and inflation; and (iv) assessing the output

gap position incorporating financial conditions

and infrastructure constraints. The agenda will

also include studies on inflation such as: (i) a reassessment of the Phillips curve relationship in

India; (ii) an analysis of food inflation in the recent

period – particularly in terms of behaviour of

perishables; and (iii) an assessment of exchange

rate pass-through.

III.37 Data suggest that investment has remained

depressed despite significant monetary easing

and pass-through of such easing to bank lending

rates. Capacity utilisation has also remained

below the long-term trend. In this backdrop, a

study will be conducted to analyse factors that

have impacted investment activity and capacity

utilisation.

III.38 The GST in India has been implemented

from July 01, 2017. This is expected to remove

distortions and improve productivity. A study will

be conducted to assess the impact of GST on

growth, including the second order effects.

III.39 The MCLR introduced in April 2016 has not

performed as expected. Although the introduction

of MCLR resulted in better transparency on fixing of lending rates by banks vis-à-vis the base

rate system, banks have frequently adjusted

the spreads, thereby impeding transmission

to the actual lending rates. A detailed inter-departmental

study will be conducted to examine

various aspects of MCLR with a view to bringing

necessary refinements and exploring market rates

as alternative benchmarks.

III.40 An effective monetary transmission is the

key to successful implementation of monetary

policy. In this context, the following studies will

be conducted. First, post-demonetisation, there

have been large swings in liquidity. A study will be

conducted to assess the impact of liquidity swings

on the transmission of monetary policy impulses.

Second, the poor health of the banking sector

has been a matter of concern. This appears to

have impacted monetary transmission as banks

have either not responded adequately to cuts in

the policy rate or did not cut their lending rates.

A detailed study will be conducted to assess

whether banks’ poor health has impeded monetary transmission. Third, the Basel III liquidity coverage

ratio (LCR) was introduced in a phased manner

beginning January 2015. In order to ensure the

smooth implementation, the Reserve Bank has

allowed a carve out of 11.0 per cent of statutory

liquidity ratio (SLR). The Reserve Bank has also

reduced SLR to provide flexibility to banks to meet

the LCR norms by January 2019 when banks have

to reach the minimum LCR of 100 per cent. The

initial experience suggests that the introduction

of LCR has altered banks’ activity in the call

money market in the post-LCR regime. A study

will be undertaken to assess as to whether the

introduction of the LCR has impacted monetary

transmission.

III.41 As surplus liquidity is expected to pose

a challenge, especially in the first half of 2017-

18, the Reserve Bank will endeavour to manage

liquidity using multiple instruments available at

its disposal. However, the use of any particular

instrument will be situation-specific with the sole

objective of ensuring closer alignment of the

operating target to the policy repo rate.

|