I am indeed privileged to be sharing the dais with stalwarts and thank ASSOCHAM for giving me this opportunity to speak on challenges in implementing Basel III in India. 2. Basel III framework was basically the response of the global banking regulators to deal with the factors, more specifically those relating to the banking system that led to the global economic crisis or the great recession. In the advanced economies, there was a huge fiscal cost for protecting the financial system, which those governments did not want a repeat of. The framework therefore sought to increase the capital and improve the quality thereof to enhance the loss absorption capacity and resilience of the banks, brought in a leverage ratio to contain balance sheet expansion in relation to capital, introduced measures to ensure sound liquidity risk management framework in the form of liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and net stable funding ratio (NSFR), modified provisioning norms and of course enhanced disclosure requirements. 3. In India, Basel III capital regulation has been implemented from April 1, 2013 in phases and it will be fully implemented as on March 31, 2019. Further, we have also introduced Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) to be implemented by banks in India from January 1, 2015 with full implementation being effective from January 1, 2019. We have issued draft guidelines on implementation of Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR). We are also working on other areas of evolving regulations, especially those which are of critical importance from Indian perspective. 4. As this event is on challenges in implementing Basel III let me begin with the assumption that there are challenges. Any change, big or small, of whatever nature brings with it challenges. The issue one must look at is whether the challenges are as onerous as one would think them to be and whether the challenges are worth facing up to. 5. The first element in this debate was whether we needed Basel III at all for a country like India. On this, Dr. Subba Rao, the then Governor of RBI1 made an interesting point and I quote him: “One view, although not explicitly spelt out in that form, is that India need not adopt Basel III, or should adopt only a diluted version of it, so as to balance the benefits against the putative costs. To buttress this view, it is argued that Basel III is designed as a corrective for advanced economy banks which had gone astray, oftentimes taking advantage of regulatory gaps and regulatory looseness, and that Indian banks which remained sound through the crisis should not be burdened with the ’onerous’ obligations of Basel III. The Reserve Bank does not agree with this view. Our position is that India should transit to Basel III because of several reasons. By far the most important reason is that as India integrates with the rest of the world, as increasingly Indian banks go abroad and foreign banks come on to our shores, we cannot afford to have a regulatory deviation from global standards. Any deviation will hurt us both by way of perception and also in actual practice. The ‘perception’ of a lower standard regulatory regime will put Indian banks at a disadvantage in global competition, especially because the implementation of Basel III is subject to a “peer group” review whose findings will be in the public domain. Deviation from Basel III will also hurt us in actual practice. We have to recognize that Basel III provides for improved risk management systems in banks. It is important that Indian banks have the cushion afforded by these risk management systems to withstand shocks from external systems, especially as they deepen their links with the global financial system going forward.” 6. Once we take this postulate for granted, and in fact it needs to be, let us see what the challenges are: Capital What are the factors that lead to higher capital? 7. The first set of Basel III reforms agreed in later part of 2010 tackled the issue of numerator part of regulatory capital ratio. While minimum total capital requirements were kept unchanged at 8% of the RWA, the definition of various components of capital and its composition were thoroughly revised to ensure that capital performs its intended role of loss absorption. The minimum common equity requirement was raised from 2% level, before the application of regulatory adjustments, to 4.5% after the application of stricter adjustments. This meant that common equity requirement was effectively raised from 1% to 4.5%. The Tier 1 capital, which includes common equity and other qualifying financial instruments based on stricter criteria, was increased from 4% to 6%. It has also been agreed that there would be a capital conservation buffer of 2.5% above the regulatory minimum requirement to be met with common equity. This effectively increases the total capital requirements from present 8% to 10.5%. In our case, the level of capital increases from 9% to 11.5%, if capital conservation buffer is taken into account. In this context, it may be pertinent to note that post-crisis, major banks in advanced economies have raised their capital adequacy level significantly. In general, globally banks have raised their CET1 ratio by almost 400 bps during last four years. And importantly, this is mainly by way of fresh infusion of equity capital. A comparative capital position of major Indian banks vis-à-vis major global banks as indicated in graph 1 below:  As may be appreciated, capital levels of our banking system need to go up significantly if our major banks have to compete globally. During recent years, the capacity of banks specifically, for the PSBs to generate capital internally have adversely affected mainly due to sharp deterioration in the asset quality. At the same time, banks have not made concerted efforts to shore up their capital level outside of the usual budgetary support. After the phased-in implementation of Basel III, the RBI apprised the Government of India on the need to initiate appropriate measures to ensure that PSBs have plans and a well-defined strategy for meeting the capital requirements from a medium-term perspective. In this context, it is heartening to note that Government has initiated several measures such as allowing PSBs to access market to raise capital subject to ensuring minimum shareholding of the Government of 52% and recent unleashing of a plan for revamping PSBs called ‘Indra dhanush’ These measures show the intent and commitment of Government to provide additional budgetary support to these banks to ensure that PSBs remain adequately capitalized to support economic growth. The improvement in the equity capital and all other measures taken together may also facilitate raising non-equity capital (AT1 and Tier 2), as the markets / investors would be more receptive to those banks holding a higher level of common equity. 8. The second element in the capital framework is the leverage ratio. We have advised banks that they would be monitored on a leverage ratio of 4.5%. We are watching this closely. Leverage ratio generally does not adjust the assets for risk weights and therefore would need the required capital for a given balance sheet. We have seen on the basis of the RW profile of banks that the leverage ratio is not acting as the binding factor for most banks in India. The graph 2 below shows the interaction between Tier 1 leverage ratios (horizontal axis) and Tier 1 risk-based capital ratios (vertical axis) of domestic banks. The diagonal line represents the points where the Tier 1 capital requirements would remain the same for meeting both the ratios. Therefore, for banks above the diagonal line, the leverage ratio requires more capital than risk-based capital ratio and vice-versa.  To ensure that the leverage ratio acts as a credible back-stop measure, the Reserve Bank would continue to monitor the leverage ratio behaviour of Indian banks and also the developments of other related regulatory framework before finalizing the appropriate level of leverage ratio for Indian banks. 9. Another element that could lead to higher capital is the changes in the Risk Weighted Assets, more specifically, on account of proposed revisions to the standardised approaches for risk measurements. The BCBS intends to avoid reliance on credit ratings for determining risk weights for credit risk given the lessons learnt from the crisis. Although this is work in progress, under the proposed revised framework, banks would be required to utilise a set of risk drivers like leverage of the entity, NPAs, etc. to determine the appropriate risk weight. Similarly, for market risk, there would be a requirement to compute sensitivities (delta, gamma, etc.) on a deal level for computing RWAs. For measuring counterparty credit risk (CCR) in the derivatives, both in the OTC and exchange-traded derivatives, the existing current exposure method (CEM) will be replaced with a revised method called standardised approach for CCR (SA-CCR). Besides, talks are already underway to review the existing treatment of sovereign assets under Basel framework wherein exposure to sovereign requires zero or very little capital charge. These proposals will alter the way banks compute RWAs. Besides, a new explicit capital charge for interest rate risk for banking book positions is also proposed to be introduced. Further, specific to the advanced approaches for risk measurement, the Basel Committee is undertaking a strategic framework review with a view to enhancing simplicity, reducing complexity and at the same time ensuring that the framework remains risk sensitive. The Committee would also examine the potential for interaction amongst various policy prescriptions amongst themselves as well as with the monetary policy objectives to assess whether there is any potential room for material inconsistency which may severely undermine the overall objectives. 10. The fourth element impacting capital requirements is provisioning. IFRS 9 requires provisioning based on expected loss provisions. The BCBS only recently put out a discussion paper on accounting issues in estimating expected loss. 11. No doubt the new framework will need additional capital. Specific to the PSBs, Government has announced the infusion of Rs 70000 crore over the next four years. But the need of the hour is as much for the PSBs to improve their internal processes to enhance efficiency, optimise the capital allocation and deal with the asset quality issue. There are several measures internal to banks and they must look at them than just look at the external factors. A lot can be done to improve credit underwriting, manage the credit post disbursement and recoveries. There is thus scope for improvement of internal accruals as a source of capital, and improving efficiency, risk management system and asset quality management are one of the most important parts of that effort so that external capital is not required for cleaning up balancer sheets unlike what would be happening now. 12. When capital requirement increases, there is impact on growth. There are varying estimates of this impact. The Macroeconomic Assessment Group (MAG) established in February 2010 by Financial Stability Board and Basel Committee on Banking Supervision to coordinate an assessment of the macroeconomic implications of the Basel Committee’s proposed reforms, estimates that bringing the global common equity capital ratio to a level that would meet the agreed minimum requirement and the capital conservation buffer would result in a maximum decline in GDP, relative to baseline forecasts, of 0.22%, which would occur after 35 quarters. In terms of growth rates, annual growth would be 0.03 percentage points (or 3 basis points) below its baseline level during this time. This is then followed by a recovery in GDP towards the baseline. Banks can also respond to the higher capital requirements by reducing costs or becoming more efficient. In fact a less stable financial system could have more deleterious consequences. The extent to which the great recession put global economic growth back is proof enough of this. Liquidity 13. The second Challenge comes from Liquidity Framework. The global crisis underscored the importance of liquidity management by banks. The apparently strong banks ran into difficulties when the interbank wholesale funding market witnessed a seizure. In fact I have mentioned elsewhere too that for me it is only a matter of time before a liquidity risk degenerates into a solvency risk for a bank and therefore needs to be avoided. The crisis proved that and had it not been for central bank support, the crisis toll could have gone beyond what we saw. The LCR and the NSFR Frameworks basically address this problem. 14. In the Indian context, any discussion on the LCR issue brings to the fore the fact that it runs parallel to SLR requirement. We have over a period of time reduced SLR and of the current level of 21.5%, a portion i.e.7 % is available for LCR as well. There is always the contention that the parallel need to maintain SLR and LCR poses an additional burden on the banks in India. We are aware of this concern and already communicated our intention to reduce the SLR requirements in a phased manner. However, there are several factors that would have to be addressed before we can move further to address the potential overlap. 15. The NSFR framework is draft for consultation. We are looking at the comments received and will come out with the final guidelines taking into consideration the responses to the extent we can accommodate them. Technology 16. The Third challenge is technology. As I mentioned earlier, BCBS is in the process of making significant changes in standardised approach for computing RWAs for all three risk areas. These revised standardised approaches them selves will be quite risk sensitive and will be dependent on a number of computational requirements. Further, BCBS has proposed that for those banks which are under advanced approaches, RWAs based on standardised approaches may work as some kind of floor. BCBS is working on calibration of these floors. Banks may need to upgrade their systems and processes to be able to compute capital requirements based on revised standardised approach. Skill Development 17. The fourth challenge is skill development. I see this as a requirement both in the supervised entities and within the Reserve Bank. Implementation of the new capital accord requires higher specialised skills in banks. In fact it requires a paradigm shift in risk management. The governance process should recognise this need and make sure that the supervised entity gears up to it. Risk awareness has to spread bank-wide, the manner of doing business that measures risk adjusted returns needs to permeate the system. Top management and the Human Resource Development Policy of banks thus need to get tuned to this requirement. We in the Reserve Bank also need to hone up our skills in regulating and supervising banks under the new system. We see this as an ongoing process and are continuously working towards skill improvement. Governance 18. One can have the capital, the liquid assets and the infrastructure. But corporate governance will be the deciding factor in the ability of a bank to meet the challenges. BCBS has added a separate principle on corporate governance in its core principles for effective banking supervision which were revised in 2012. It is interesting to note that before 2012, there was no separate principle on corporate governance. I think global community is recognising the importance of corporate governance and is trying to fix the issues. Thus while strong capital gives financial strength, it cannot assure good performance unless backed by good corporate governance. Element of conservatism in minimum standards 19. Several speakers mentioned about the super equivalence issue. Let me add my bit to that discussion before I conclude. There is a general feeling that we have put in place a more stringent framework than what Basel Norms require. Of course one would point out to the 9 percent CRAR, the 4.5 leverage ratio, the SLR running parallel with LCR, the higher CCF for OTC derivatives and the like. We need to see this in a context. I have already dealt with the SLR-LCR issue. On capital, all I can say is that in the ultimate analysis, on an aggregate basis, it does not make much difference. We must also appreciate that relatively much longer recovery process of defaulted loans, shorter history of ratings assigned by rating agencies in Indian conditions putting certain constraint on benchmarking them against the international standards, relatively large population of unrated borrowers especially in mid and SME corporate sectors, market risk factors exhibiting more volatilities, etc. add challenges. Besides, Pillar 2 process and related add-on capital requirements is also yet to be fully stabilised. The higher prescription of 9% minimum requirements in comparison to Basel minimum of 8% may be seen in the above context. Moreover, in an economy whose financial system is dominated by banks, one has to build more resilience than if it were not the case. We have also announced two banks as DSIBs based on the criteria of size, interconnectedness, complexity and substitutability. 20. I must add here that the recent Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme of the BCBS did find our regulations to be fully compliant on all issues relating to capital. Such an affirmation that the banks are working in a regulatory environment consistent with global standards is an assurance to the international financial system that they can do business with Indian banks like with any other. It would be instructive to quote the BCBS Chairman2 here “I would like to remind you that the Basel framework is a minimum standard and members are free to go beyond the minimum. We actually encourage that, and most jurisdictions have adopted minimum requirements that exceed the global standard. Super-equivalences are often found in developing and emerging market economies, where banks have a higher risk profile. The local regulators therefore set higher minimum requirements”. Incidentally, it may also be appreciated that we are not the only jurisdiction having prescribed a higher minimum capital standards. Several other jurisdictions, particularly Asian countries, have proposed higher capital adequacy ratios under Basel III as may be seen from Table below: | Sample of Basel Member Jurisdictions with Higher Capital Adequacy Norms | | (in percentage) | | Jurisdictions | Minimum Common Equity Ratio | Minimum Tier 1 Capital Ratio | Minimum Total Capital Ratio | | Basel III (BCBS) | 4.5 | 6.0 | 8.0 | | India | 5.5 | 7.0 | 9.0 | | Singapore | 6.5 | 8.0 | 10.0 | | South Africa | 6.0 | 8.25 | 11.5 | | China | 5.0 | 6.0 | 8.5 | | China (D-SIBs) | 6.0 | 7.0 | 9.0 | | Russia | 5.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 | | Brazil | | | 11.5 till 2019 | | Switzerland | 4.5-10 | 6-13 | 8-19 | 21. Let me conclude now. I began by saying why it is necessary to implement Basel III in India. I looked at the various challenges that it brings but argued that we cannot see any challenge in isolation. The Basel rules seek to make banks more resilient and risk aware. Such a banking system is always better than an unstable one. We cannot overlook the fact that a crisis is better prevented than faced because the aftermath of the crisis is costlier than the incremental cost that one incurs to prevent it. I suppose the deliberations in today’s meet would not be oblivious to this reality. Let me thank you for your attention. __________________________________________________________________________________ Inaugural address delivered by Shri N. S. Vishwanathan, Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India on the occasion of National conference on BASEL III Implementation: Challenges for Indian banking system organised by The Associated Chambers of Commerce & Industry of India with support of National Institute of Bank Management (NIBM) on August 31, 2015. Assistance provided by Mr. Ajay Kumar Choudhary and Mr Rajnish Kumar in preparing this speech is gratefully acknowledged.

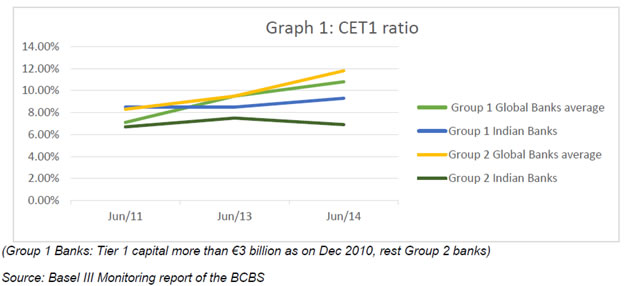

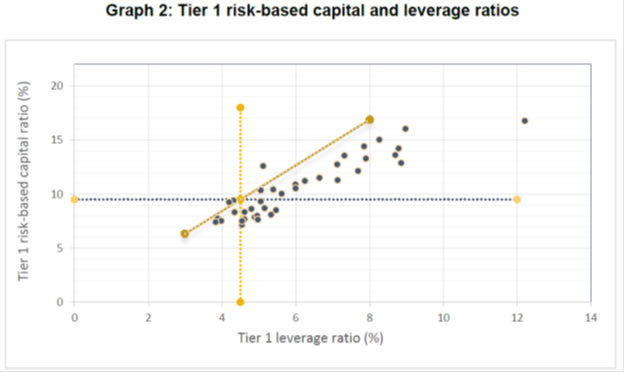

|