by Ramesh Jangili#, Srinivasa Sai Charan Marisetty^ and Yashoda Bai Mood^ We assess the financial literacy (FL) levels in India through a primary survey, as prescribed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). We obtained responses through a structured questionnaire and summarised FL broadly on three components — knowledge, behaviour and attitude. Our results show that some with relatively better financial knowledge levels, are lagging in financial behaviour or attitude and vice-versa. The findings reinforce many stylised facts; however, heterogeneity observed between the FL components within socio-economic groups necessitates policy intervention. While the RBI’s initiatives aim at improving financial knowledge for various groups, initiatives to improve the other two aspects may be supported by a targeted approach. Introduction Financial inclusion (FI) has been defined in many possible ways. According to the World Bank, “Financial inclusion means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs and are delivered responsibly and sustainably.” Though several definitions exist for FI1, access, usage, quality and cost of financial services are collectively used to define FI. Broadly, all definitions allude that FI is having access to the formal financial system for availing basic financial services at a reasonable cost. Low-income households may have to borrow from friends, family, or usurious moneylenders, to meet any unexpected expenditures. They have little awareness and limited access to financial services that could protect their financial resources in exigent circumstances. The provision of uncomplicated, small, affordable products can help bring low-income families into the formal financial sector (Joshi, 2013). Bringing low-income groups within the perimeter of the formal banking sector protects their financial wealth and other resources during exigent circumstances. FI helps to mitigate the exploitation of vulnerable sections by usurious money lenders by facilitating easy access to formal credit (Bhaskar, 2013). Steps towards achieving FI are also echoed in the Gandhian philosophy: “Sarvodaya through Antyodaya – Welfare of all through the upliftment of the weakest” (Das, 2021). Traditionally, FI was considered to be important only for achieving a country’s developmental goals and for eradicating poverty. But FI is also equally important for achieving monetary policy goals as financially included people can smoothen their consumption by drawing down their savings in difficult times and saving in good times. Thereby, people become both more interest-sensitive and responsive to monetary policy decisions. This would result in effective dampening of inflation and output volatility (Patra, 2021). Financial Literacy (FL) is an important adjunct in effectively promoting FI, tacitly protecting consumers and eventually ensuring financial stability. FI and FL2 need to go hand in hand, to enable a common person to understand the needs and benefits of the products and services offered by the formal financial institutions. In contrast, financial illiteracy can add to consumers’ inability in classifying and understanding the fine print from a large volume of information, which in turn leads to an information asymmetry between the financial intermediary and the consumer. FL, however, can bridge this gap and help consumers narrow the information divide. Therefore, FL is also an essential prerequisite for ensuring consumer protection. From a systemic perspective, greater FL can aid in better allocation of resources and thereby raise the long-term growth potential of the economy. As alluded by the former RBI Governor, Dr D. Subbarao, the ultimate goal of FL is to empower people to act in their self-interest and these actions accrue benefits to the economy at large. Only when consumers are fully aware of the available financial products, they can evaluate the merits and demerits of each product, then negotiate and avail the product of their choice, resulting in their empowerment in a very meaningful way. They will know enough to demand accountability and seek redressal of grievances. This, in turn, will enhance the integrity and quality of financial markets (Subbarao, 2010). Given the importance of FI, the RBI has constructed a composite Financial Inclusion Index3 (FI-Index) to capture the extent of FI across the country (Sharma et.al., 2021). Further, the ambitious agenda set by the National Strategy for Financial Inclusion (NSFI), 2019-24 and the National Strategy for Financial Education (NSFE), 2020-25 to achieve a financially literate and empowered India, makes one ponder over the present literacy levels across the country (RBI, 2020 and RBI, 2021). It is a common practice to conduct periodic surveys to assess the level of FL (OECD, 2020) and in the Indian context, National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE) carried out a Financial Literacy and Inclusion Survey in 2018-19 (NCFE, 2019). But it has been more than three years since the survey was carried out. The RBI has also undertaken several initiatives during the period to promote FL across the country (Annex I). However, no pertinent information is available on the current levels of FL. Therefore, a survey is conducted to assess the current levels of FL4 and the findings are presented in this study. The rest of the study is organised into five sections. We discuss the survey methodology and data collection process in next section. The descriptive profile of respondents is briefly presented in section 3. Prevalence of component-wise5 FL is presented in section 4 along with overall FL. FL scores and their relationship with respondents’ characteristics are discussed in section 5. Summary and policy suggestions are presented in the last section. 2. Survey Methodology and Data Collection Primary data was collected through a structured questionnaire for this study (Annex II). We prepared the questionnaire broadly in line with OECD/INFE Toolkit for measuring FL, which was drawn from OECD working paper (Kempson, 2009). Further, similar type of questionnaire was used as part of the OECD FL6 exercise. Our questionnaire comprises of 28 questions, divided into two blocks viz., FL and identification. The RBI, Hyderabad office sets up a stall in the annual Numaish7 exhibition to spread financial awareness among the visitors. Historically, we observed that people from various age groups, gender, occupation, qualification, domicile, states, etc. visit the exhibition, thereby providing a heterogeneous sample. Hence, we made an attempt to conduct a field-level survey to assess the level of FL. The survey approach involved two stages. In the first stage, we collected responses amongst Numaish visitors. We requested them to share the questionnaire on their social media platforms, and the second stage involved, thus received responses. Thus, a two-stage sampling methodology was adopted to obtain the sample. The first stage respondents are Numaish visitors, and the second stage is a snow-ball sampling originating from the first stage respondents. Though the questionnaire was drafted in English, we did ask the respondents in either English, Hindi or Telugu, to expand and diversify the sample. Cumulatively over a period of 45 days, 584 responses were received. About 40 per cent of the responses were received through the survey questionnaire at the stall (first stage), and the remainder were received through online mode (second stage). 3. Descriptive Profile of the Survey Respondents 3.1 Population Groups/Revenue Centres We found an adequate representation of respondents across population groups/revenue centres, despite targeting Numaish visitors for the survey. Respondents were primarily from metropolitan areas, followed by urban and rural regions (Chart 1). Lack of awareness of classification in terms of semi-urban and rural areas might have led to the lowest share of 9 per cent from the semi-urban population. It can be attributed to the ubiquitous awareness in terms of well-known village, town and city concept, avoiding semi-urban areas. Overall, the sample is representative of various population groups/revenue centres. 3.2 Gender Owing to the voluntary nature of the survey response, the gender distribution is highly skewed, with a higher male representation (Chart 2). Male responses are much higher at 84 per cent for rural and semi-urban population groups, whereas they account for about 75 per cent for urban and metropolitan groups.

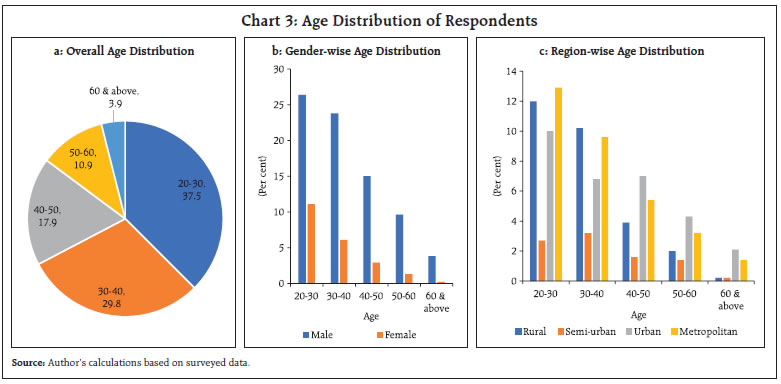

3.3 Age The sample has representation from all the age groups, with maximum number of respondents falling within the age group of 20-29 years, followed by 30-39 years (Chart 3). Further, the sample is representative of various socio-economic groups within each age group. 3.4 Distribution of Respondents by Occupation and Education Level We found that majority of the respondents are salaried employees, followed by others and self-employed/business (Table 1). Majority of respondents possess either graduation or post-graduation and above educational qualifications. However, it is worth mentioning that various open universities offer graduation courses to those students, who could not complete their formal schooling, subject to the candidate clearing Bachelor’s Preparatory Programme.8 These admissions would have resulted in the enrolment of a majority of the school dropouts into graduation courses, thereby completing the same in a couple of years.

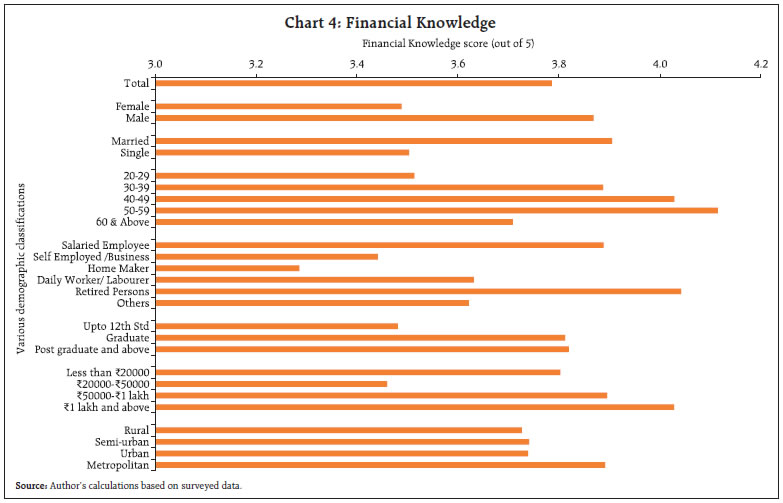

| Table 1: Distribution of Respondents – Occupation vis-à-vis Education Level | | (Per cent) | | S. No. | Occupation | Education Level | | 12th Std and below | Graduate | Postgraduate and above | Total | | 1. | Salaried Employee | 1.6 | 33.2 | 31.8 | 66.6 | | 2. | Self-Employed / Business | 2.7 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 11.1 | | 3. | Daily Worker/ Labourer | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 3.0 | | 4. | Homemaker | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 2.1 | | 5. | Retired Persons | 0.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.1 | | 6. | Others | 2.0 | 7.5 | 3.6 | 13.0 | | 7. | Total | 8.6 | 49.3 | 42.1 | 100.0 | We also observed that almost all salaried employees have their education level as graduation and above. The respondents with education level 12th std and below are majorly self-employed or are engaged in other activities. Few responses were received from respondents, who have at least completed graduation but working as a daily labourer or homemaker. 3.5 Distribution of Respondents by Income Level Respondents are spread across various income groups (Table 2). The majority of the respondents from rural areas have monthly earnings of less than ₹20,000, and the majority of respondents from the metropolitan region have monthly remuneration in the range of ₹50,000-₹1lakh, validating the general income perception. | Table 2: Distribution of Respondents – Income Group vis-à-vis Population Group | | (Per cent) | | S. No. | Income Group Classification | Population Group Classification | | Rural | Semi-urban | Urban | Metropolitan | Total | | 1. | Less than ₹20,000 | 20.9 | 3.0 | 9.8 | 2.7 | 36.4 | | 2. | ₹20000-₹50000 | 4.3 | 2.3 | 6.6 | 9.6 | 22.9 | | 3. | ₹50000-₹1 lakh | 2.5 | 1.3 | 8.2 | 11.3 | 23.2 | | 4. | ₹1 lakh and above | 0.5 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 8.9 | 17.5 | | 5. | Total | 28.2 | 9.1 | 30.2 | 32.5 | 100.0 | As a result, the data is representative of various population groups, occupational groups, income levels, both males and females, and also has representation from diverse age groups, making the sample suitable for further analysis and drawing inferences. 4. Prevalence of Financial Literacy 4.1 Prevalence of Financial Knowledge Questions (Q10-Q14 of Annex II) assess an understanding of the risk-return relationship, inflation, diversification and awareness of grievance redressal mechanism. We presume that those who indicated ‘TRUE’ to Q11-Q14 and ‘Yes’ to Q10 understand the risk-return relationship, inflation, diversification and Ombudsman mechanism, respectively. We have assigned a score of one to each correct answer, and therefore the respondent with all correct answers scores a maximum of five under financial knowledge. Most of the respondents are comfortable with risk-return relations and inflation but relatively less comfortable with diversification (Table 3). Further, 71 per cent of the respondents are aware of the Reserve Bank’s Ombudsman Scheme. Understanding of risk-return is found to be high amongst retired persons and among the respondents in the 50-59 years age group. On the other hand, respondents in the daily worker/labourer occupation group have a lower understanding of the risk-return relationship. While respondents with an average monthly income of ₹1 lakh and above have a higher cognisance of inflation, homemakers have a lower understanding of inflation. Awareness about the diversification aspect is generally lower in the sample. Respondents in the age group of 60 & above have a much lower appreciation of diversification. Regarding the ombudsman scheme, 83.3 per cent of retired persons are aware of the scheme, whereas only 35.7 per cent of homemakers are aware of the same. | Table 3: Financial Knowledge – Proportion of Respondents with Correct Answer | | (Per cent) | | Demographic Classification | Risk-Return1 | Risk-Return2 | Inflation | Diversification | Ombudsman | | Gender | | | | | | | Female | 70.9 | 76.4 | 81.1 | 61.4 | 59.1 | | Male | 83.4 | 82.9 | 83.4 | 62.8 | 74.4 | | Marital Status | | | | | | | Married | 83.5 | 83.0 | 86.1 | 64.5 | 73.5 | | Single | 74.0 | 78.0 | 75.1 | 57.8 | 65.3 | | Age | | | | | | | 20-29 | 75.9 | 79.0 | 77.2 | 56.7 | 62.5 | | 30-39 | 82.8 | 79.9 | 84.6 | 65.1 | 76.3 | | 40-49 | 80.2 | 86.8 | 87.7 | 73.6 | 74.5 | | 50-59 | 90.2 | 86.9 | 90.2 | 65.6 | 78.7 | | 60 & above | 87.5 | 79.2 | 83.3 | 41.7 | 79.2 | | Occupation | | | | | | | Salaried Employee | 82.6 | 83.1 | 84.9 | 65.5 | 72.7 | | Self-Employed /Business | 72.1 | 79.4 | 76.5 | 54.4 | 61.8 | | Homemaker | 78.6 | 85.7 | 64.3 | 64.3 | 35.7 | | Daily Worker/ Labourer | 73.7 | 63.2 | 73.7 | 73.7 | 78.9 | | Retired Persons | 91.7 | 87.5 | 87.5 | 54.2 | 83.3 | | Others | 77.0 | 77.0 | 82.4 | 54.1 | 71.6 | | Educational Qualification | | | | | | | Up to 12th Std | 78.8 | 75.0 | 73.1 | 57.7 | 63.5 | | Graduate | 83.0 | 84.4 | 80.2 | 62.5 | 71.2 | | Postgraduate and above | 78.3 | 79.5 | 88.1 | 63.5 | 72.5 | | Average Monthly Income Group | | | | | | | Less than ₹20000 | 77.9 | 79.3 | 79.8 | 58.7 | 84.6 | | ₹20000-₹50000 | 71.1 | 81.5 | 74.8 | 59.3 | 59.3 | | ₹50000-₹1 lakh | 88.1 | 82.1 | 86.6 | 65.7 | 67.2 | | ₹1 lakh and above | 88.8 | 85.0 | 94.4 | 70.1 | 64.5 | | Place of Residence | | | | | | | Rural | 76.4 | 74.5 | 78.3 | 59.0 | 84.5 | | Semi-urban | 79.6 | 79.6 | 79.6 | 66.7 | 68.5 | | Urban | 79.5 | 81.3 | 82.4 | 60.8 | 69.9 | | Metropolitan | 85.5 | 88.1 | 88.1 | 65.8 | 61.7 | | Overall | 80.7 | 81.5 | 82.9 | 62.5 | 71.1 | On assigning the financial knowledge score in the sample to Q10-Q15, we found that the overall score for financial knowledge is 3.89 (out of 5). We found that respondents in the age group of 40-59 years, those who retired and those with an average monthly income of ₹1 lakh and above scored four or more in the prevalence of financial knowledge (Chart 4). On the other hand, homemakers scored the lowest. Respondents whose occupation is self-employed and whose average monthly income is in the range of ₹20000-₹50000 also have lower financial knowledge scores.  Females have lower knowledge scores when compared to males. Similarly, unmarried respondents have lower scores when compared to married. Young respondents (less than 30 years of age) have a lower score, and the score improves with age, with the exception of those aged above 60 years. Respondents with lower educational backgrounds have a lower score. Respondents residing in the metropolitan area have higher financial knowledge scores when compared to others. 4.2 Prevalence of Financial Behaviour We assess the financial behaviour of the respondents based on their responses to money management (Q1); household budget (Q2); managing living cost (Q7); saving behaviour (Q8); evaluation of available options while selecting financial product/service (Q5) questions in Annex II; together with their response on a five-point Likert scale (1-strong disagreement to 5-strong agreement) to monitoring financial affairs (Q6f), setting long term financial goals and working to achieve them (Q6f), bill payment behaviour (Q6d) and affordability trait (Q6a). The respondents responsible/involved in day-to-day decisions either solely or jointly are considered to possess prudent financial behaviour. Similarly, those who have a household budget and meet their living costs through their income, those who are saving with formal financial institutions and those who exercise due diligence while choosing financial products/services possesses positive traits and are exhibiting financially prudent behaviour. Further, the respondents who indicate strong disagreement on the five-point Likert scale (Q6), indicate extravagant financial behaviour, a negative trait. We have assigned a score of one each to the respondents when they are personally or jointly responsible for money and finance management, when they maintain a household budget and when they can meet their living costs. Further, a score of one is given to the respondents with active saving behaviour, 0.5 for passive saving behaviour, and zero for not saving. Similarly, a score of one is awarded for due diligence, 0.5 for partial due diligence while selecting financial products or services, and zero for not exercising due diligence at all. The responses on a five-point Likert scale were converted into numerical scores based on the proximity to the desired response. For instance, strong agreement to bill payment behaviour is awarded a score of one and strong disagreement is awarded a zero. While the responses such as agree, neutral and disagree were awarded a score of 0.75, 0.50 and 0.25, respectively. Therefore, the respondents can obtain a maximum score of nine under financial behaviour. The average score for financial behaviour is 6.65 out of a maximum attainable score of 9 (Chart 5), higher than the average behaviour score of 5.3 (out of 9) for OECD member countries and also higher than the minimum threshold score10 of 6 (out of 9) mentioned by OECD-INFE. The average score obtained at the aggregate level is 74 per cent of the maximum possible score. About 69 per cent of the respondents achieved the minimum target score of 6, thus recognising and acting on the remaining 31 per cent of the respondents should be involved in the action plan going forward. 4.3 Prevalence of Financial Attitude Financial attitude is evaluated based on respondents’ attitude towards spending, saving and investing money. Specifically, we analyse the respondent’s opinion on a Five-point Likert scale on the statements (Q6b, Q6c and Q6e of Annex II). The strong agreement indicates a negative financial attitude towards spending, saving and planning money. We have assigned a financial attitude score for all the respondents in the sample based on their opinion on a Five-point Likert scale. A higher score is assigned to the respondents who exhibit more positive attitude towards spending, saving and planning money. Each of the statements described above focuses on short-term preferences and is likely to hinder financial resilience and well-being. The aim is to capture the level of financial attitude amongst the respondents, by considering it to be proportion to the level of disagreement with each statement. Higher levels of disagreement indicates that the respondent possesses better financial attitude. We found that the overall financial attitude score was 1.97 out of a maximum of 5 (Chart 6). Specifically, we found the financial attitude of daily workers/labourers to be meagre, at just 1.58 (out of 5). Financial attitude is higher amongst the respondents from semi-urban and urban areas, and also in the age group of 60 & above. The minimum threshold score mentioned by OECD-INFE is 3 (out of 5) for OECD-12 countries. Surprisingly, only 25 per cent of the respondents in our sample scored three or more, an issue of concern and concerted efforts are needed in this direction. 5. Financial Literacy Scores The FL score consists of the following three components (discussed in the previous section) and ranges between 0 to 19. -

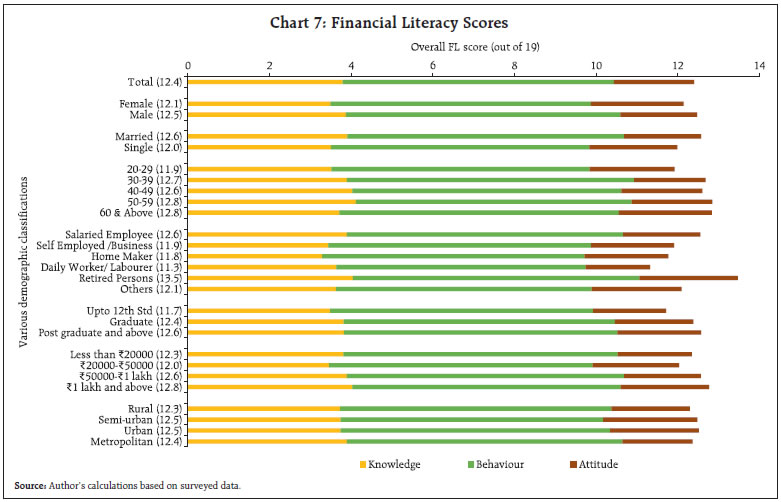

Financial knowledge score (takes the range of 0 to 5) -

Financial behaviour score (takes the range of 0 to 9) -

Financial attitude score (takes the range of 0 to 5) We reiterate that the methodology followed to arrive at the FL score is broadly in line with the approach described in the OECD-INFE Toolkit for measuring FL. We assigned scores based on the appropriate response to a set of questions ascertaining individual attributes, and the overall score11 is a simple aggregation of individual scores. Overall FL score is 12.4 out of a maximum attainable score of 19, demonstrating significant room for improvement (Chart 7). We observe heterogeneity within the FL components (knowledge, behaviour and attitude) among the respondents’ groups. Despite relatively high levels of financial knowledge in certain groups, the overall score is low because of their lower scores in financial behaviour/attitude. We observed higher FL scores for retired persons (13.5) followed by respondents who are above 50 years of age (12.8) and whose monthly income is more than ₹1 lakh (12.8). On the other hand, it is the lowest among respondents whose occupation is daily worker/labourer (11.3). The highest FL score of 69.6 per cent represents a decent level of financial knowledge, financially prudent behaviour and lower attitudes towards spending, saving and planning money (Table 4). FL scores increased with the increased level of education and average monthly household income. Surprisingly, FL scores did not vary significantly based on respondents’ place of residence.

| Table 4: Financial Literacy Scores – Normalised to 100 | | (Per cent) | | Financial Literacy (19=100), Knowledge (5=100), Behaviour (9=100) and Attitude (5=100) | | | Financial Literacy | Knowledge | Behaviour | Attitude | | Gender | | | | | | Female | 61.4 | 69.8 | 70.9 | 45.4 | | Male | 63.0 | 77.4 | 74.7 | 37.6 | | Marital Status | | | | | | Married | 63.6 | 78.1 | 75.3 | 37.8 | | Single | 60.3 | 70.1 | 70.4 | 43.0 | | Age | | | | | | 20-29 | 59.8 | 70.3 | 70.3 | 41.6 | | 30-39 | 64.0 | 77.8 | 78.2 | 35.0 | | 40-49 | 64.2 | 80.6 | 73.2 | 39.7 | | 50-59 | 64.9 | 82.3 | 75.0 | 39.6 | | 60 & above | 66.4 | 74.2 | 76.1 | 45.6 | | Occupation | | | | | | Salaried Employee | 63.4 | 77.8 | 75.2 | 37.9 | | Self-Employed/ Business | 60.3 | 68.8 | 71.5 | 40.6 | | Homemaker | 58.2 | 65.7 | 71.5 | 41.0 | | Daily Worker/ Labourer | 56.5 | 72.6 | 67.9 | 31.6 | | Retired Persons | 69.6 | 80.8 | 78.0 | 48.3 | | Others | 61.0 | 72.4 | 69.6 | 44.1 | | Educational Qualification | | | | | | Up to 12th Std | 58.7 | 69.6 | 71.6 | 35.8 | | Graduate | 62.4 | 76.3 | 73.8 | 38.5 | | Post-graduate and above | 63.7 | 76.4 | 74.4 | 41.0 | | Average Monthly Household Income | | | | | | Less than ₹20000 | 61.4 | 76.1 | 74.7 | 36.4 | | ₹20000-₹50000 | 61.0 | 69.2 | 71.7 | 42.4 | | ₹50000-₹1 lakh | 63.9 | 77.9 | 75.4 | 37.6 | | ₹1 lakh and above | 65.4 | 80.6 | 73.0 | 43.3 | | Place of Residence | | | | | | Rural | 61.4 | 74.5 | 73.8 | 38.5 | | Semi-urban | 62.9 | 74.8 | 71.4 | 46.2 | | Urban | 63.3 | 74.8 | 73.4 | 43.4 | | Metropolitan | 62.8 | 77.8 | 75.0 | 34.4 | | Overall | 62.6 | 75.7 | 73.9 | 39.3 | The average scores hide salient disparities. We found that heterogeneity exists between the components of FL within the socio-economic groups of the respondents. Some with relatively high levels of financial knowledge, such as males and respondents from metropolitan areas, score average in the overall FL due to their lower financial attitude scores. Some with relatively high levels of financial behaviour, such as respondents in the age group of 30-39 years, scored average FL due to their lower financial attitude score. Similarly, some with relatively better financial attitudes, such as female respondents and respondents from semi-urban areas, score average in the overall FL due to their lower financial knowledge and behaviour scores. Specifically, we observed that female respondents’ lower financial knowledge offset their better financial attitudes. On the other hand, married respondents’ better score in financial knowledge/ behaviour balanced their lower financial attitude. Therefore, FL camps must target to enhance knowledge of female respondents and of those residing in semi-urban areas; and target attitude development for remaining respondents’ groups so as to benefit the entire population in deprived areas. Thus, ensuring that everyone is fully cognisant of their financial decisions, aimed at self-development, besides helping in nation-building process. 6. Summary and Policy Suggestions We carried out a survey to assess the level of FL at Numaish All India Industrial Exhibition during April-May 2022. The data was collected through a structured questionnaire prepared broadly in line with OECD/INFE Toolkit for measuring FL. A two-stage sampling methodology was adopted. The first-stage respondents were the Numaish visitors, and the second stage is snowball sampling originating from the first-stage respondents. Our analysis reinforces most of the stylised facts, viz., higher financial knowledge among males and those with stable incomes. We also found that financial knowledge increases with income, age, education and proximity to metropolitan areas. We observed that financial behaviour is in sync with financial knowledge. On the financial attitude front, which was observed to be lower, females exhibited better financial attitudes as compared to males. FL, overall, was observed to be relatively lower amongst the younger population, those with lower educational qualifications and without a stable income source. We observed that respondents with an income up to ₹20,000 per month have higher knowledge as compared to respondents earning between ₹20,000 to ₹50,000. We found daily workers and labourers scoring low on financial behaviour aspect, despite having higher financial knowledge. While the common perception is that financial attitude improves with age, income, and proximity to a metropolitan area, the survey reveals that those in the age group of 30-39 score low on financial attitudes compared to the other age groups. Further, the respondents earning between ₹50,000 to ₹1 lakh per month score low in terms of financial attitude. We also found that heterogeneity exists between the components of FL (knowledge, behaviour and attitude) within the socio-economic groups of the respondents. Some with relatively high levels of financial knowledge such as males and respondents from metropolitan areas, have average scores in terms of overall FL owing to lower financial attitude scores. Similarly, those with relatively high levels of financial behaviour such as respondents in the age group of 30-39 years, had an average overall FL score due to their lower financial attitude score. Similarly, some with relatively high levels of financial attitude such as female respondents and respondents from semi-urban areas, are lagging in financial knowledge and Financial behaviour scores. It is therefore important to broaden the canvas of FL to include financial knowledge, behaviour and attitude, with special emphasis on those target groups, which were found to be lagging as compared to the rest. References: Atkinson, A., & Messy, F. A. (2012). Measuring financial literacy: Results of the OECD/International Network on Financial Education (INFE) pilot study, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15. Awasthy, S., Balachandran, R., Gupta, B., Saroy, R., Khobragade, A., Singh, G., Misra, R. and Dhal, S.C. (2023). Basic and Digital Financial Literacy in the Last Mile: A Snapshot from Rural West Bengal. RBI Bulletin, May. Bhaskar, P. V. (2013). Financial inclusion in India–an assessment. Speech delivered by Executive Director, RBI at the MFIN and Access-Assist Summit, on December 10. Chakrabarty, K. C. (2013). Financial Inclusion in India: Journey so far and way forward. Keynote address delivered by Deputy Governor, RBI at Finance Inclusion Conclave Organised by CNBC TV 18, on September 06. Das, S. (2021). Financial Inclusion – Past, Present and Future. Inaugaral address delivered by the Governor, RBI at the Economic Times Financial Inclusion Summit, on July 15. Joshi, D. P. (2013). Financial inclusion: Journey so far and Road ahead. Speech delivered by Executive Director, RBI at the Mint Conclave on Financial Inclusion, on November 28. Kempson, E. (2009). Framework for the development of financial literacy baseline surveys: A first international comparative analysis. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 1. NCFE (2019). Financial Literacy and Inclusion in India – Final Report, National Centre for Financial Education, Navi Mumbai. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020). OECD/INFE 2020 international survey of adult financial literacy. Ouachani, S., Belhassine, O., & Kammoun, A. (2021). Measuring financial literacy: A literature review. Managerial Finance, 47(2), 266-281. Patra, M. D. (2021). Financial Inclusion Empowers Monetary Policy. Keynote address delivered by Deputy Governor, RBI in the project on Financial Inclusion, a joint initiative by the IIMA, IRMA and CIIE, on December 24. RBI (2020). National Strategy for Financial Inclusion (NSFI): 2019-2024, Reserve Bank of India, Jan 10. RBI (2021). National Strategy for Financial Education: 2020-2025, Reserve Bank of India, March 17. Sharma, A. K., Sengupta, S. and Roy, I. (2021). Financial Inclusion Index for India, RBI Bulletin, September. Singh, B., Rajesh, R., Golait, R. and Samuel, K. L. (2023). Determinants of Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion in North-Eastern Region of India: A Case Study of Mizoram. DRG Study No. 48, Reserve Bank of India. Subbarao, D. (2010). Financial Education: Worthy and Worthwhile. Comments by the Governor, RBI at the RBI-OECD International Workshop on Financial Literacy, on March 22.

Annex I: Initiatives of RBI towards FL Recognising the importance of FL and its role in achieving the envisaged objectives of FI, RBI has adopted an integrated approach towards FI and FL. In this direction, RBI undertook the following initiatives in coordination with the banking system: 1. National Strategy for Financial Inclusion (NSFI) 2019-2024 laid down action plans to be implemented, to make financial services available, accessible and affordable to all citizens in a safe and transparent manner to support inclusive growth through a multi-stakeholder approach. 2. National Strategy for Financial Education (NSFE) 2020-2025 provided a road map for a coordinated approach towards FI, FL and consumer protection. 3. Banks in India were mandated to set up Financial Literacy Centres (FLCs) to extend FL services by adopting a tailored approach, and 1380 FLCs across India are functional as on date. 4. The Centre for Financial Literacy (CFL) Project is being set up across the country at the block level by March 2024 to enhance the effectiveness by community-led participatory approach for greater FL. As on date, 1107 CFLs are operational and cater to 3321 blocks across the country. 5. One of the strategic goals of the NSFE 2020-2025 is to integrate FL content into the school curriculum so as to instil financial concepts at a younger age. So far, 15 state educational boards have included FL content in their curriculum, in addition to central boards. 6. Financial Education material (which include comic books, films, messages, games and access link to RBIO Scheme, etc.) is made available on the RBI website in English, Hindi and 11 vernacular languages. 7. Distributing pamphlets, leaflets and comic books to spread financial awareness, in addition to skits, stalls in local fairs/exhibitions, and participating in information/literacy programmes. 8. Setting up a monetary museum, virtually, to create awareness about money and banking among the public and spread knowledge about the history of money. 9. Use of mobile FL vans by banks in select States. These initiatives are expected to strengthen financial education at the grass-roots level so as to realise the vision of creating a financially aware and empowered India. Besides, RBI started publishing FI-Index to measure the extent of FI in India. | Annex II: Survey Questionnaire – Financial Literacy Block 1: Financial Literacy 1) Who is responsible for day-to-day decisions about money, in your household? a) You

b) You and your partner

c) You and another family member

d) Your partner

e) Another family member (or family members)

f) Don’t know 2) Does your household have a budget? (A household budget is used to decide what share of your household income will be used for spending, saving or paying bills.) a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know 3) Have you heard of any of these types of financial products? (Yes/No) 4) Do you currently hold/use any of these types of products (personally or jointly)? (Yes/No) | | (Q3) | (Q4) | | A savings account | Yes/No | Yes/No | | A debit card | Yes/No | Yes/No | | A credit card | Yes/No | Yes/No | | Internet banking | Yes/No | Yes/No | | Mobile banking | Yes/No | Yes/No | | National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT) | Yes/No | Yes/No | | Immediate Payment Service (IMPS) | Yes/No | Yes/No | | BHIM UPI/GPay/PhonePe/etc | Yes/No | Yes/No | | A microfinance loan | Yes/No | Yes/No | | An unsecured bank loan (ex. personal loan) | Yes/No | Yes/No | | A bank loan secured on property | Yes/No | Yes/No | | Insurance (health or term or any) | Yes/No | Yes/No | | A pension fund | Yes/No | Yes/No | | Mutual funds | Yes/No | Yes/No | 5) How did you choose your last financial product/service? a) Considered several financial products from various banks/companies

b) Considered various financial products offered by a particular bank/company

c) Selected the product prescribed by a particular bank/company

d) Not considered any alternative financial products at all

e) Couldn’t find similar alternative financial products in the market, despite making efforts 6) How much you agree or disagree that each of the statements applies to you. Please use a scale of 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree) a) Before you buy something you carefully consider whether you can afford it (1/2/3/4/5)

b) You tend to live for today and let tomorrow take care of itself (1/2/3/4/5)

c) You find it more satisfying to spend money than to save it for the long term (1/2/3/4/5)

d) You pay your bills on time (1/2/3/4/5)

e) You are prepared to risk some of your own money when saving or making an investment (1/2/3/4/5)

f) You keep a close personal watch on your financial affairs (1/2/3/4/5)

g) You set long term financial goals and strive to achieve them (1/2/3/4/5) 7) Sometimes people find that their income does not quite cover their living costs. Has this happened to you in the last 12 months? a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t want to answer 8) In the past 12 months have you been saving money in any of the following ways? a) Saving cash at home or in your wallet

b) Depositing money in your bank

c) Giving money to family to save on your behalf

d) Saving in an informal saving club

e) Investing in market linked products (mutual funds, shares, bonds, etc.)

f) Has not been actively saving 9) Do you access digital financial services? a) Yes

b) No (Digital financial services are financial services accessed and delivered through digital channels, including via mobile devices) 9a) If No, reasons for not accessing a) Not aware of these services/lack of sufficient knowledge

b) Not comfortable in using technology

c) Lack of trust in digital financial services

d) Adequate grievance redressal mechanism is not in place

e) Others 10) Are you aware of Reserve Bank’s Ombudsman Scheme? a) Yes

b) No (A Scheme for resolving customer grievances in relation to services provided by entities regulated by Reserve Bank of India, typically Banks/NBFCs. Customer can lodge compliant against any RBI regulated entity by visiting https://cms.rbi.org.in/cms/indexpage.html#) 11) An investment with a high return is likely to be high risk a) True

b) False

c) don’t know 12) If someone offers you the chance to make a lot of money, there is also a chance that you will lose a lot of money. a) True

b) False

c) don’t know 13) High inflation means that the cost of living is increasing rapidly a) True

b) False

c) don’t know 14) It is usually possible to reduce the risk of investing in the stock market by buying a wide range of stocks and shares. a) True

b) False

c) don’t know Block 2: Identification 1) Name: 2) Gender: a) Male

b) Female

c) Other 3) Marital status: a) Married

b) single 4) Age (years): a) 20-29

b) 30-39

c) 40-49

d) 50-59

e) 60 & above 5) Occupation a) Salaried Employee

b) Self Employed/Business

c) Homemaker

d) Daily Worker/Labourer

e) Retired Persons

f) Others 6) Educational Qualification a) Illiterate

b) Below 5th Std.

c) Below 10th Std.

d) Below 12th Std.

e) 12th Std.

f) Graduate

g) Post-Graduate and above 7) Average monthly Household Income a) Less than ₹20,000

b) ₹20,000-₹50,000

c) ₹50,000-₹1 lakh

d) ₹1 lakh and above 8) Place of residence a) Metropolitan

b) Urban

c) Semi-urban

d) Rural |

|