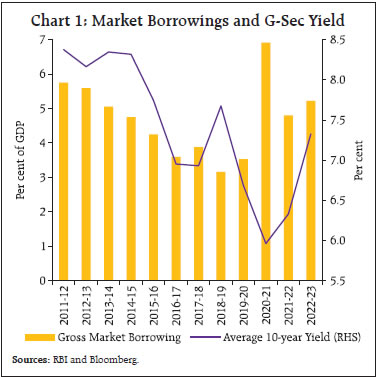

by Ipsita Padhi, Priyanka Sachdeva, Samir Ranjan Behera, Atri Mukherjee, and Indranil Bhattacharyya^ This article revisits the debate on the “Conventional” versus the “Keynesian” view on the key drivers of G-sec yields while analysing the nexus between the size of the government borrowing programme and yields on government securities. Based on data spanning January 2012 – May 2023, an event study analysis finds a significant instantaneous impact of budget and monetary policy announcements on G-sec yields. Results from an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model suggest that the amount of government borrowing, monetary policy actions, US treasury yields, inflation and banking system liquidity have a bearing on domestic bond yields. Introduction The government securities (G-sec) market or the sovereign bond market plays a key role in the financial architecture of a developing economy in several ways. First, it is the operating platform through which most central banks alter liquidity conditions in the financial system through open market operations (OMOs) – the purchase/sale of government securities. Second, it is an important element of the term structure of interest rates in the economy that facilitates the transmission of monetary policy signals from the short end of the yield curve to the longer end impacting economic activity. Third, it is the primary source of raising funds to meet the budgetary funding gap of governments that incur fiscal deficits continuously. Fourth, the G-sec market provides the benchmark yield – the risk-free rate – to investors for the pricing of other financial market instruments (Zaja et al., 2018). Fifth, government securities act as eligible collateral for financial entities (banks and other intermediaries) in availing central bank liquidity facilities. As such, the government securities market is a vital cog in the wheel of economic activity. From an investor’s perspective, close monitoring of G-sec yields is also crucial for assessing the potential gains/losses from their investment portfolios, which include government bonds (Pinho and Barradas, 2021). Post-globalisation, the availability of the global financial savings pool has made the price (and yield) of G-sec in emerging market economies (EMEs) increasingly dependent on global investors’ preferences, with country-specific risk factors playing a more limited role (Kumar and Okimoto, 2011). Thus, factors like global risk appetite, interest rates, savings and investment have gained importance in the pricing of long-term sovereign debt instruments, although government deficits/debt levels and other country-specific factors continue to play a significant role (Naidu et al., 2016). Therefore, a clear understanding of the determinants or drivers of government bond yields, viz., fiscal and monetary policy measures, regulatory announcements, significant domestic and global macroeconomic developments and geo-political news, is essential for market participants and policymakers. Although substantial cross-country literature exists, the debate on the determinants of bond yields and the relative importance of its key drivers remains unsettled (Schrynmakers, 2016). The divergence in findings is attributable to factors such as the choice of empirical methods, sample diversity, the nature of proxies measuring the various risk factors, and the periodicity of these studies (Pepino, 2013). The existing literature brings to light two contrasting strands of thought, viz., (i) the Conventional view; and (ii) the Keynesian view. The conventional view states that higher government debt and deficit (as a proportion of GDP) exert upward pressure on government bond yields, based on the classical loanable funds’ theory of interest (Min et al., 2003; Ardagna et al., 2007; Baldacci and Kumar, 2010; Tokuoka and Lam, 2011; Gruber and Kamin, 2012; Martinez et al., 2013; Cebula, 2014; Perovic, 2015; Poghosyan, 2014; Paccagnini, 2016). In contrast, the Keynesian view suggests that the central bank’s policy rate, along with other monetary policy instruments, plays a decisive role in determining G-sec yields, while fiscal indicators such as deficit and debt have no role (Kregel, 2011; Simoski, 2019). The relationship between the government’s fiscal condition and long-term interest rates has been an intensely debated issue. For instance, the deterioration of the long-term budget outlook in the United States raised questions as to whether and to what extent the expected rise in federal government debt will impact long-term interest rates (Cebula, 2014). In this regard, fiscal consolidation in the late 1990s by the United Kingdom and Canada did lower government bond yields. Furthermore, the yield differential on government securities attributable to the difference in the fiscal position of the eurozone economies drew wide attention (Akram and Das, 2017). On the other hand, the proposition that stressed government finances in Japan had affected government bond yields remains contentious (Akram and Das, 2014a; 2014b). All these contrasting arguments call for closer empirical scrutiny of the nexus between the government’s fiscal position and G-sec yields. The empirical evidence on factors determining Indian G-sec yields is quite varied. While short-term interest rates and the pace of inflation are found to be key determinants of G-sec yields, fiscal variables such as deficit and debt hardly have any impact (Akram and Das, 2019). In contrast, another study inter alia found that the deficit and borrowing requirements of the government have an impact on G-sec yields (Kapur et al., 2018). These conflicting evidences call for a relook at the debate between the “Conventional” vis-a-vis the “Keynesian” view. Against this backdrop, the rest of the article is divided into four sections. After a brief review of the literature in Section II, Section III presents some stylised facts on the evolution of government borrowing and G-sec yields in the Indian context. The empirical methodology and results are presented in Section IV, while the final Section sets out the concluding observations. II. Related Literature The theoretical literature on the impact of fiscal policy on long-term domestic yields is somewhat discordant without any consensus. Consistent with the loanable funds approach, neoclassical theory postulates that a rise in fiscal deficit reduces national savings and raises interest rates (Elmendorf and Mankiw, 1998). In contrast, the Ricardian view suggests that any increase in government deficit is perceived by forward-looking economic agents as a mere shift in tax liability to the future; therefore, rational agents would save more today (in an intertemporal sense) to meet higher tax obligations later, which would mitigate/offset the adverse impact on interest rates (Barro, 1974). A more acceptable view is that if taxes are non-distortionary and individuals are heterogeneous, debt accumulation may be consistent with a rise in interest rates in the short-run but may not have a pronounced impact on long-term bond yields (Mankiw, 2000). In an open economy framework with international capital mobility, the link between fiscal deficit and interest rate is tenuous as fiscal policy influences interest rates only through its impact on the risk premium (Mundell, 1963). Much of the earlier work on the relationship between the government’s fiscal balance and interest rate pertains to advanced economies (AEs), though studies on EMEs proliferated in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC). Many EME-centric studies concede that the role of fiscal balance, amongst other domestic and global factors, is crucial in driving interest rates. In a study comprising both AEs and EMEs, higher fiscal deficits and public debt are found to increase long-term interest rates significantly, with the magnitude varying because of the ingrained differences in institutional, fiscal and other structural conditions; moreover, these effects are exacerbated in times of global risk aversion and heightened uncertainty (Baldacci and Kumar, 2010). Taking cognisance of increased inflows into EMEs engendered by the low-interest rate environment post-GFC, many subsequent studies have incorporated global factors (US interest rates, VIX) in their analysis of EMEs. In a panel-based study of 10 EMEs that explicitly modelled the foreign participation in the domestic bond market, the fiscal balance-to-GDP ratio was found to have a positive effect on long-term bond yields, whereas domestic monetary aggregates and real economic activity did not have any significant impact. In addition, long-term yields were found to be influenced by changes in inflationary expectations, policy interest rates, and foreign participation in domestic bond markets (Peiris, 2010). Expectations regarding fiscal deficits and government debt were found to play a significant role in determining domestic bond yields during periods of high-risk aversion, while real GDP and inflation expectations were more important during tranquil times (Jaramillo and Weber, 2013a). Moreover, the extent of EMEs’ vulnerability to these factors depended on country-specific characteristics, including financial sector openness, fiscal fundamentals, and external current account balance (Jaramillo and Weber, 2013b). Domestic factors such as expectations of short-term interest rates and the fiscal balance were found to be relatively more important in driving bond yields of EMEs than global factors such as US bond yields and the VIX (Miyajima et al., 2015). The role of fiscal deficit was also important in the transmission of exchange rate risk to domestic bond yields in EMEs, i.e., less favourable fiscal conditions tended to increase the sensitivity of local currency bond yields to expected exchange rate depreciation (Gadanecz et al., 2018). In the Indian context, the literature on the role of fiscal indicators in determining interest rates is mixed. A recent study employing the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) methodology found that interest rates and fiscal deficits are positively associated, while money supply and inflation have a negative relationship with the real rate of interest in the long run (Rani and Kumar, 2016). Similarly, government deficit and borrowing requirements – apart from the Reserve Bank’s policy rate, prevailing liquidity conditions, non-resident investment flows into domestic bond markets as well as sovereign bond yields in the U.S. and other major AEs – are found to impact G-sec yields (Kapur et al., 2018). While examining the transmission channel from fiscal policy to interest rates for the period Q1:1996 to Q3:2018 in a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) framework, it was found that fiscal deficit had a direct (though temporary) impact on interest rate in the short run while the indirect impact through inflation was larger in the long run. Besides, foreign interest rate shocks also had a positive impact on domestic interest rates in the long run (Mohanty and Bhanumurthy, 2020). Using similar methodology, a study on the relationship between public debt, inflation, interest rate, economic growth, and investment revealed that public debt (of the central as well as combined government) had an adverse impact on economic growth and a hardening impact on long-term interest rates (Mohanty and Panda, 2020). In contrast, some other studies found a negligible role of fiscal deficit in determining interest rates – both the short- and the long-term – in India. Changes in the short-term interest rate, after controlling for other important variables like changes in inflation rate and the pace of economic activity, were found to be the key drivers of government bond yields (Chakraborty, 2012). Moreover, the government’s fiscal position did not have any hardening impact on bond yields in the short run (Akram and Das, 2015a; 2015b), which supported the Keynesian view. Subsequently, the authors extended their study to the long run using ARDL methodology and concurred with their earlier findings on short-run dynamics; additionally, longer-term bond yields were found to be positively associated with the short-term rate, industrial production, and inflation (Akram and Das, 2019). III. Government Borrowing and G-Sec Yields Gross market borrowing of the central government (as a proportion of GDP) declined steadily from 5.8 per cent in 2011-12 to around 3.6 per cent in 2016-17 as the government embarked on fiscal consolidation. Concomitantly, the yield on 10-year government paper moderated from an average of 8.4 per cent in 2011-12 to 7.0 per cent in 2016-17 (Chart 1). Yields, however, rose intermittently during 2013-14 and H1:2014-15 as the Reserve Bank undertook liquidity tightening measures after the taper tantrum-induced market volatility, and subsequently increased policy rates to arrest inflation pressures in accordance with the ‘glide path’ for disinflation as recommended by an expert committee (RBI, 2014).1 Barring these episodes, G-sec yields eased in tandem with the reduction in government borrowing, reaching a trough of 6.4 per cent in January 2017, as unprecedented surplus liquidity conditions triggered a sharp decline in yields following the withdrawal of ₹500 and ₹1000 denomination currency notes from circulation in November 2016.  Yields, however, started hardening from H2:2017-18 inter alia due to increased market borrowings, higher crude oil prices and rising US yields. Market borrowings moderated in 2018-19, but yields continued to harden during H1:2018-19 because of rising crude oil prices and capital outflows triggered by global trade tensions and faster than anticipated normalisation of US monetary policy. In H2:2018-19, yields moderated on the back of large-scale OMO purchases by the Reserve Bank, easing crude oil prices and decline in the US treasury yields. In 2019-20 and 2020-21, market borrowings surged as the COVID crisis impinged on government revenues, even as the pandemic necessitated higher spending. Nevertheless, yields declined from 8.09 per cent in September 2018 to a decadal low of 5.82 per cent in July 2020, driven by the extraordinary monetary and liquidity measures undertaken by the Reserve Bank, including Operation Twist (OT), wherein the Reserve Bank simultaneously bought long-term and sold short-term government securities (generally of identical amounts) to compress the term premium (Talwar et al., 2021; Patra and Bhattacharyya, 2022). Market borrowing remained elevated in 2021-22, but yields were supported by the Reserve Bank’s secondary market G-sec acquisition programme (G-SAP). With the termination of the G-SAP programme in October 2021 and the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in Q4:2021-22, yields hardened. During 2022-23, bond yields were conditioned by domestic inflation dynamics, domestic policy normalisation, lower than anticipated market borrowing programme of the central government for 2023-24 (announced in February 2023) and investor demand for safe assets following the banking turmoil in some AEs in March 2023. In addition, yields were significantly influenced by the US Fed actions. IV. Methodology and Results To examine the interlinkages of government borrowing and G-sec yields, a dual empirical strategy is adopted; first, the instantaneous announcement effect of Union Budget and monetary policy is examined in an event study (ES) framework; second, an ARDL model is used to estimate both the short run dynamics and the long run impact of government borrowing on G-sec yields. Announcement Effect Important policy announcements like the Union Budget or monetary policy can impact government bond yields. The instantaneous impact of such announcements on the benchmark 10-year G-sec yield is examined in an event study (ES) framework following the recent literature (Hartley and Rebucci, 2020; Talwar et al., 2021). The analysis is based on daily data for the period January 2012 to May 2023, which include 76 monetary policy and 12 Union Budget announcements. Usually, budget and monetary policy announcements are made in the forenoon well within trading hours; thus, the difference between closing and opening yield on the date of the announcement, controlled for other factors, captures the announcement effect. To assess the announcement effect, two separate equations are estimated in which intraday change in 10-year benchmark G-sec yield is regressed on its own lag and Union Budget announcement as well as monetary policy announcement dates (as dummies) with control for other main variables that can impact the intraday yields (Model 1 and 2, respectively). The impact of the two announcements is estimated separately as they are not coincidental. The control variables used for the analysis include global factors such as international crude oil prices; intraday liquidity position measured by net LAF to NDTL ratio2; and market volatility measured by India VIX. While the dependent variable, i.e., the intraday change in 10-year G-sec yield and the control variable India VIX, is stationary at level, the other control variables are found to be stationary at the first difference (Table 1). | Table 1: ADF Unit Root Test | | Variable | Level | First Difference | | Intra-day change in 10-year G-sec Yield | -51.077*** | -19.762*** | | Crude Oil Prices | -1.958 | -54.893*** | | India VIX | -6.045*** | -20.623*** | | Net LAF to NDTL | -1.973 | -9.958*** | Note: (1) * represents probability value; *, ** and *** imply significance at 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent, respectively.

(2) The ADF unit root test is based on daily data.

Source: Authors’ estimates. | In the estimated results, the positive coefficient of the Union Budget dummy in Model 1 suggests that G-sec yields have generally hardened on Budget days (Table 2). The positive and significant coefficient of the monetary policy dummy in Model 2 confirms that yield moves in tandem with monetary policy announcements – policy tightening raises yields and vice versa. Among the control variables, a rise in crude oil prices and higher market volatility hardens G-sec yields in both models. Surplus liquidity captured in the positive net LAF to NDTL ratio has a staggered sobering impact on yields, as indicated by the negative coefficient of the lagged term. Diagnostic test, viz., the ARCH-LM test, confirms robustness of the estimated models. Thus, the announcement impact of both the Union Budget and monetary policy is positive and significant. | Table 2: Results of Announcement Effect | | Explanatory/Control Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | | Dependent Variable: Intraday change in 10-year G-sec yield (∆ Y) | | Constant (C) | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | | Lag (∆ Y) | 0.0548*** | 0.0448** | | Budget Dummy | 0.0887*** | | | Monetary Policy Dummy | | 0.0116*** | | ∆ Crude Oil Prices | 0.0010*** | 0.0010*** | | ∆ India VIX | 0.0021*** | 0.0025*** | | ∆ Liquidity (-2) | -0.0061** | -0.0061** | | Diagnostic (P-value) | | | | Arch-LM Test | 0.7446 | 0.6037 | Note: * represents probability value; *, ** and *** imply significance at 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent, respectively.

Source: Authors’ estimates. | ARDL Model In addition to government borrowing, G-sec yields are likely to be impacted by several other factors, as suggested in the literature, viz., policy rate, inflation expectations, liquidity conditions and global factors. The impact of US treasury yields is in consonance with the global financial cycle hypothesis (Miranda-Agrippino and Rey, 2021), which posits that the financing conditions and the monetary policy stance in the premier global financing centre, i.e., the US sets the tone for other countries. For EMEs, currency appreciation goes hand in hand with compressed sovereign bond spreads, even for local currency sovereign bonds, due to a reduction in the credit risk premium (Hofmann et al., 2019). Accordingly, the following independent variables are included in the ARDL model: government borrowing as proportion of G-sec volume (BORRVOL) to capture bond supply dynamics (Patra et al., 2021), weighted average call rate (WACR) as a proxy for the RBI’s policy repo rate, inflation as measured by the year-on-year (y-o-y) change in consumer price index (CPI), 10-year US treasury yield (UST) and exchange rate movements captured by y-o-y changes in the USD-INR. Liquidity condition is incorporated as a dummy variable in which surplus liquidity, as proxied by the net LAF position, is assigned a value of 1 and deficit as 0. The empirical investigation is conducted using monthly data, from January 2012 to May 2023. Sources of all data are detailed in Annex – Table 1. Before model estimation, all variables are tested for stationarity (Table 3). Since the variables are found to be a combination of stationary [I(0)] and non-stationary series [I(1)], an ARDL framework is preferred. The ARDL model integrates the short-run impact of the variables and the long-run equilibrium through an error correction term, helping to assess both short-run and long-run relationships between the variables (Sharma and Mittal, 2021). Before applying the ARDL model, the existence of long-run relationships among the variables needs to be tested using a bounds test. The ARDL model can be specified as: Where, p and q are the lag orders of the dependent andindependent variables and ut indicates the residual term. Furthermore, the error correction representation of the ARDL model can be specified as: | Table 3: ADF Unit Root Test | | Variable | Level | First Difference | | 10-Year G-sec Yield | -1.967 | -7.725*** | | BORRVOL | -5.475*** | -8.349*** | | WACR | -1.983 | -8.546*** | | UST | -1.597 | -8.422*** | | CPI | -1.977 | -5.132*** | | USDINR | -3.292** | -8.443*** | Notes: (1) * represents probability value; *, ** and *** imply significance at 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent, respectively.

(2) The ADF unit root test is based on monthly data.

Source: Authors’ estimates. | where ∆ denotes the first difference; b0 represents the intercept term; b1 to b7 represent the short-run coefficients; p and q are the lags of dependentand independent variables, respectively; ECMt-1 is the error correction term; Ø denotes the speed of adjustment, and ωt depicts the residual term. Short-run and Long-run Dynamics The results from the ARDL bounds test for cointegration are presented in Table 4. Since the F-statistic is higher than the upper bound critical value, cointegration between variables/ long-run relationship is confirmed. The estimates from the long-run form and error correction model are presented in Table 5. The results suggest a positive and significant impact of borrowing to volume ratio, WACR, US T-bill yield and CPI on G-sec yields in the long run. A rise in the ratio of government borrowing to volume by 100 basis points (bps) can lead to an increase in 10-year G-sec yield by around 19 bps in the long-run. Similarly, an increase of 100 bps in the WACR can result in an increase of around 20 bps in the 10-year yield over time. US treasury yield movements also have a sizeable impact on domestic bond yield, in consonance with the results of several studies that long-term domestic interest rates are also dependent on global factors (Kumar and Okimoto, 2011; Abhilasha et al., 2023). Inflationary pressures also result in higher yields, possibly due to higher inflation premiums demanded by investors. In the short-run equation, US treasury yield, USDINR and liquidity position have a significant impact. The negative coefficient for the LAF dummy implies the softening impact of surplus liquidity on G-sec yields. Similarly, currency appreciation is also found to have a negative impact on bond yields (corroborating Hofmann et al., 2019). The error correction term, that represents the speed of adjustment if a deviation occurs from the long-run steady-state value, is negative and significant – its coefficient of about -0.16 indicates that the short-run deviation from the steady-state path gets corrected in about six months. | Table 4: Bounds Test for Cointegration | | F-Statistic | 95 per cent lower bound | 95 per cent upper bound | Inference | | 4.45 | 2.39 | 3.38 | Cointegrated | | Source: Authors’ estimates. | The diagnostics and stability tests confirm the robustness of the estimates. The Breusch–Godfrey Serial Correlation Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test failed to reject the null hypothesis of no serial correlation with a probability chi-square of 0.1440. Similarly, the null hypothesis of homoscedastic errors could not be rejected by the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey heteroskedasticity test with a probability chi-square of 0.6753. The stability of the long-run coefficients in the ARDL model is confirmed by the cumulative sum (CUSUM) of recursive residuals and the cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals (Annex – Chart 1). | Table 5: Results from ARDL Estimation | | Variable | Dependent Variable: G-sec yield | | Long-run | | | BORRVOL | 0.1914* | | WACR | 0.1989** | | UST | 0.5730*** | | CPI | 0.1281** | | C | 4.1465*** | | Short-run | | | D(10-yr G-sec(-1)) | 0.3238*** | | D(UST) | 0.2101*** | | D(USDINR) | -0.010* | | LAFDUMMY | -0.0874*** | | Error-correction term | | | CointEq (-1)* | -0.1554*** | | Diagnostics test | | | Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test | 0.1440 | | Heteroskedasticity Test: Breusch- Pagan-Godfrey | 0.6753 | Notes: (1) * represents probability value; *, ** and *** indicate significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent level, respectively.

(2) Table reports probability chi-square statistic for diagnostic tests and regression coefficients for the remaining variables.

Source: Authors' estimates | V. Conclusion While government borrowing has declined from the pandemic-induced peak of 2020-21, it stands at 5.2 per cent of GDP in 2022-23, which is higher than the decadal average of 4.5 per cent (2010-11 to 2019-20). Since the size of borrowing determines the supply of securities in the market, it is an important determinant of G-sec yield. Furthermore, sovereign bond yields are an essential conduit for the effective transmission of monetary policy to the spectrum of financial prices (through the risk premium channel) and the broader real economy. This article analysed the impact of government borrowings on G-sec yields in India, both in the short-run as well as the long-run after factoring in other relevant control variables that have a bearing on yields, such as the monetary policy stance and the global financial cycle. The results from the empirical exercise indicate that government deficit, domestic inflation, and domestic as well as global monetary policy are major driver of yields. In the short-run, banking system liquidity has a significant bearing on yields. Thus, the findings are in consonance with both the Classical and the Keynesian views. From a policy perspective, the ongoing fiscal consolidation undertaken by the government and proactive debt management policies of the Reserve Bank are contributing to an orderly movement in g-sec yields. References Abhilasha, Talwar, B. A., Kushwaha, K. M., & Bhattacharyya, I. (2023). Open Market Operations in India - An Appraisal. RBI Bulletin, January, pp 91-104. Akram, T., & Das, A. (2014a). Understanding the Low Yields of the Long-term Japanese Sovereign Debt. Journal of Economic Issues, 48(2), 331-340. Akram, T., & Das, A. (2014b). The Determinants of Long-term Japanese Government Bonds’ Low Nominal Yields. Levy Economics Institute Working Papers, 818. Akram, T., & Das, A. (2015a). Does Keynesian Theory Explain Indian Government Bond Yields? Levy Economics Institute Working Papers, 834. Akram, T., & Das, A. (2015b). A Keynesian Explanation of Indian Government Bond Yields. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 38 (4): 565–87. Akram, T., & Das, A. (2017). The Dynamics of Government Bond Yields in the Euro Zone. Annals of Financial Economics, 12(03), 1750011. Akram, T., & Das, A. (2019). The Long-Run Determinants of Indian Government Bond Yields. Asian Development Review, 36(1), 168-205. Ardagna, S., Caselli, F., & Lane, T. (2007). Fiscal Discipline and the Cost of Public Debt Service: Some Estimates for OECD Countries. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics, 7(1). Baldacci, E. & Kumar, M. (2010). Fiscal Deficits, Public Debt, and Sovereign Bond Yields. IMF Working Paper, WP/10/184. Barro, R.J. (1974). Are Government Bonds Net Wealth? Journal of Political Economy, pp. 1095-1117. Cebula, R.J. (2014). Impact of Federal Government Budget Deficits on the Longer-Term Real Interest Rate in the U.S.: Evidence Using Annual and Quarterly Data, 1960-2013. Applied Economics Quarterly, 60, 23-40. Chakraborty, L. S. (2012). Interest Rate Determination in India: Empirical Evidence on Fiscal Deficit – Interest Rate Linkages and Financial Crowding Out. Levy Economics Institute Working Papers, 744. Elmendorf, D., W., and Gregory, N., M., (1998). Government Debt. NBER Working Paper, 6470. Gadanecz, B., Miyajima, K. & Shu, C. (2018). Emerging Market Local Currency Sovereign Bond Yields: The Role of Exchange Rate Risk. International Review of Economics & Finance. Gruber, J. W., & Kamin, S. B. (2012). Fiscal Positions and Government Bond Yields in OECD Countries. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 44(8), 1563-1587. Hartley, J. & Rebucci, A. (2020). An Event Study of COVID-19 Central Bank Quantitative Easing in Advanced and Emerging Economies. SSRN Electronic Journal. Hofmann, B., Shim, I. and Shin, H. S. (2019). Bond Risk Premia and the Exchange Rate. BIS Working Papers, 775, March. Jaramillo, L., & Weber, A. (2013a). Bond Yields in Emerging Economies: It Matters What State You Are In. Emerging Markets Review, 17, 169–185. Jaramillo, L., & Weber, A. (2013b). Global Spillovers into Domestic Bond Markets in Emerging Market Economies. IMF Working Paper, 13/264. Kapur, M., John, J., & Mitra, P. (2018). Monetary Policy and Yields on Government Securities. Mint Street Memo, 16, 1-11. Kregel, J. (2011). Was Keynes’s Monetary Policy, a Outrance in the Treatise, a Forerunner of ZIRP and QE? Did He Change His Mind in the General Theory?. Levy Economics Institute, 11-04. Kumar, M. S., & Okimoto, T. (2011). Dynamics of International Integration of Government Securities’ Markets. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(1), 142-154. Martinez, L. B., Terceno, A., & Teruel, M. (2013). Sovereign Bond Spreads Determinants in Latin American Countries: Before and During the XXI Financial Crisis. Emerging Markets Review, 17, 60-75. Min, H. G., Lee, D. H., Nam, C., Park, M. C., & Nam, S. H. (2003). Determinants of Emerging-Market Bond Spreads: Cross-Country Evidence. Global Finance Journal, 14(3), 271-286. Miyajima, K., Mohanty, M., & Chan, T. (2015). Emerging Market Local Currency Bonds: Diversification and Stability. Emerging Markets Review, 22, 126–139. March. Mohanty R. K., & Bhanumurthy N. R. (2020). Revisiting the Role of Fiscal Policy in Determining Interest Rates in India. NIPFP Working Paper, 296. Mohanty, R. K., & Panda, S. (2020). How Does Public Debt Affect the Indian Macroeconomy? A Structural VAR Approach. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 14(3), 253–284. Mankiw, N. G. (2000). The Savers-Spenders Theory of Fiscal Policy. NBER Working Paper, 7571. Miranda-Agrippino, S. and Rey, H. (2021). The Global Financial Cycle, NBER Working Paper, 29327. Mundell, R. (1963). Capital Mobility and Stabilization Policy Under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 29, 475-485. Naidu A, S. H., Goyari, P., & Kamaiah, B. (2016). Determinants of Sovereign Bond Yields in Emerging Economies: Some Panel Inferences. Theoretical and Applied Economics, XXIII(3), 101-118. Paccagnini, A. (2016). The Macroeconomic Determinants of the US Term Structure During the Great Moderation. Economic Modelling, 52, 216-225. Patra, M.D., Behera, H. and John, J. (2021). A macroeconomic view of the shape of India’s sovereign yield curve. RBI Bulletin, Reserve Bank of India, June. Patra, M. D., & Bhattacharya, I. (2022). Priming Monetary Policy for the Pandemic. Economic and Political Weekly, 57(20). Peiris, S. (2010). Foreign Participation in Emerging Markets’ Local Currency Bond Markets. IMF Working Papers 10/88. Pepino, S. (2013). Sovereign Risk and Financial Crisis: The International Political Economy of the Euro Area Sovereign Debt Crisis. London School of Economics and Political Science (Doctoral Dissertation). Perović, L. M. (2015). The Impact of Fiscal Positions on Government Bond Yields in CEE Countries. Economic Systems, 39(2), 301-316. Pinho, A., & Barradas, R. (2021). Determinants of the Portuguese Government Bond Yields. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(2), 2375-2395. Poghosyan, T. (2014). Long-Run and Short-Run Determinants of Sovereign Bond Yields in Advanced Economies., Economic Systems, 38(1), 100-114. Rani, R., and Kumar, N. (2016). Does fiscal deficit affect interest rate in India? An empirical investigation. Jindal Journal of Business Research, 5(2), 87-103. Schrynmakers, J. (2016). The Determinants of Government Bond Yield Spreads in the EMU Area: A Panel Data Analysis. Research Paper of Louvain School of Management. Sharma, V., & Mittal, A. (2021). Revisiting the Dynamics of the Fiscal Deficit and Inflation in India: The Non-Linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag Approach. Ekonomika Regiona, 17(1), 318-328. Simoski, S. (2019). A Keynesian Exploration of the Determinants of Government Bond Yields for Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. Talwar, B. A., Kushawaha, K. M. & Bhattacharyya, I. (2021). Unconventional Monetary Policy in Times of COVID-19. RBI Bulletin, March, pp 41-56. Tokuoka, K., & Lam, M. W. R. (2011). Assessing the Risks to the Japanese Government Bond (JGB) Market. International Monetary Fund, 2011/292. Zaja, M. M., Jakovcevic, D., & Visic, L. (2018). Determinants of the Government Bond Yield: Evidence from a Highly Euroised Small Open Economy. International Journal of Economic Sciences, 7(2), 87-106.

Annex | Table 1: Data Sources | | Variables | Sources | | G-sec Yield | Bloomberg | | Crude oil | Bloomberg | | US treasury yield | Bloomberg | | India VIX | Bloomberg | | Net LAF to NDTL | RBI | | CPI Inflation | MOSPI | | USDINR currency | Bloomberg | | Call Rate | CCIL |

|