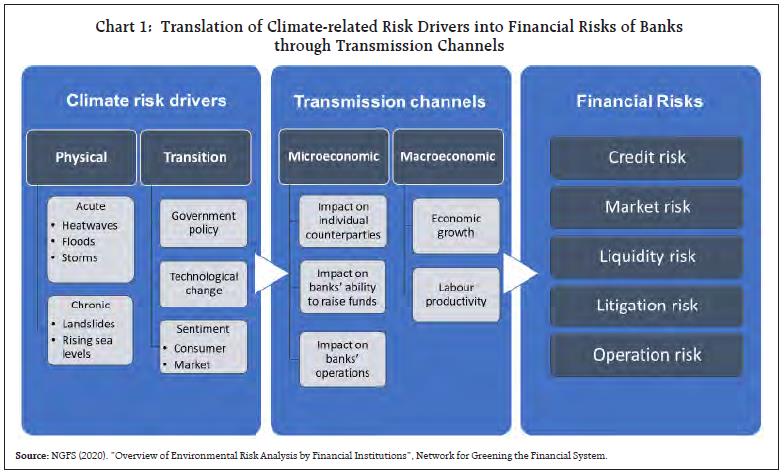

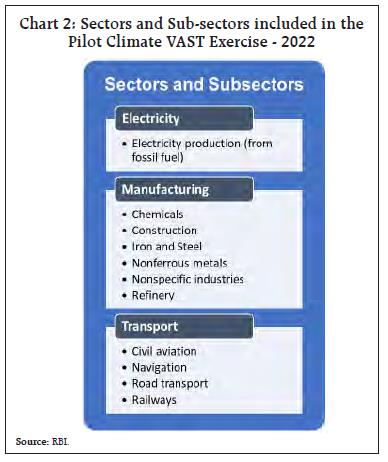

by Amit Sinha^ and Shivang Bhanvadia^ Stress testing/scenario analysis has emerged as a crucial tool for gauging the impact of climate-related risks for financial institutions, which are otherwise difficult to evaluate due to the lack of granular and reliable data. The Reserve Bank conducted a pilot climate vulnerability assessment and stress test (VAST) exercise in 2022 involving select banks. The exercise assessed the impact of climate change on banks and did not aim to assess capital adequacy or prescribe any minimum capital levels. The results showed a substantial increase in the credit loss potential1 of banks due to physical risk and transition risk. Introduction The Global Risks Report 2023 published by World Economic Forum (WEF) identified failure to mitigate climate change, failure of climate-change adaptation, and natural disasters and extreme weather events as the top three risks by severity (likely impact) over a 10-year period. Climate-related risks have the potential to affect individuals, entities (including financial institutions), and the stability of the entire financial system. The banks are vulnerable to climate risk through transmission channels mainly comprising of physical and transition risk drivers. The assessment of the potential impact arising from climate change on banks and the corresponding responses are still developing. Nonetheless, it has become necessary for banks to evaluate and manage the risks and opportunities arising from climate change. Stress testing has emerged as an important tool for regulators to assess banks’ capacity to withstand adverse scenarios and quantify the ensuing impact, if any, on the banks. It enables the banks to conduct assessment of risks on a forward-looking basis and promotes internal and external communication of the bank’s exposure to various types of risks. The outcome arising from stress testing is generally utilised by banks to take decisions on potential actions such as risk mitigation techniques, contingency plans, and capital and liquidity management under stressed conditions. Thus, stress testing has been integrated as a critical component within the risk management framework and capital planning, as envisaged in the publication of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) titled ‘An International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework’.2 A climate-related stress test is a comprehensive assessment of the impact of macroeconomic and financial variables derived from climate-economy models and aims at assessing the potential financial impact that financial institutions may face under scenarios that reflect varying degrees of risk arising from climate change vis-à-vis a given baseline scenario. The main objectives of a climate stress test are: (i) assess the potential exposure of banks to climate risks, (ii) assess the potential loss arising due to climate risks faced by banks, (iii) understand how climate change could impact the business strategy of banks, and (iv) develop climate risk management capabilities in banks. Assessing the impact of climate risk drivers through traditional stress tests presents significant challenges and differs from a traditional stress testing exercise. Climate-related risks are expected to materialise over longer time horizons than traditional financial risks. Measuring the impact of climate risk requires granular exposure data, ideally by region and sector. Unavailability of such data is a major roadblock in conducting comprehensive climate risk stress tests. The requirement of considering longer time horizons and the need of granular data increases the uncertainty in quantification of exposure sizes and assessing the impact on profitability of banks. Climate scenario analysis exercises are distinct from the regulatory stress tests. For instance, the US Federal Reserve Board while conducting its pilot climate scenario analysis indicated that while the regular stress tests are formulated to evaluate whether financial institutions possess sufficient capital to sustain their lending capacity to individuals and businesses in the event of a severe economic downturn or recession, the pilot climate exercises are exploratory in nature and carry no ramifications for bank capital or regulatory and/or supervisory consequences. In this context, this article gives a snapshot of the global efforts in monitoring the climate risk faced by banks and presents a brief on the pilot climate stress test conducted by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The rest of the article is organised in five sections. In the next section, we discuss the climate risk analysis carried out by various regulatory bodies. Section III focuses on the climate risk drivers and transmission channels of climate risk through which climate risk drivers translate into the financial risks. In section IV, we discuss the objective, approach and methodology adopted for the pilot VAST exercise. We list out the findings of exercise in section V. Lastly, a way forward on climate stress testing for regulated entities (REs) in India is presented in the section VI. II. Global Practices on Climate Risk Stress Testing Globally, regulatory authorities have taken the lead by initiating measures and are trying to understand implications that climate-related risks can have on banks and other REs. The first step in this direction was enhanced disclosure of climate-related financial risks as outlined in the 2017 report of the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB’s) Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Since then, growing efforts have been made to quantify banks’ exposure to climate risks. The approaches adopted by various central banks to monitor climate-related risks are at an early stage of development. These approaches include formulating climate disclosure requirements, ad hoc surveys, targeted information requests and use of climate risk stress test and scenario analysis. Climate scenario analysis (climate stress test) has been the primary tool employed to capture climate-related risks and credit risk is the most commonly analysed financial risk. An overview of climate risk analysis carried out by various regulatory bodies as published by FSB in the report3 titled “Supervisory and Regulatory Approaches to Climate-related Risks” is summarized below. Box I: Overview of Climate Risk Analysis carried out by various Regulatory Bodies Canada: A pilot project was carried out jointly by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and the Bank of Canada to conduct climate scenario analysis. The data gathered for banks pertained to credit risk and included information on loss-given-default (LGD), likelihood of default (PD), and anticipated credit loss (ECL). In addition to the quantitative data, a survey of the risk management practices, and governance of the participants was conducted. European Union: In 2021, the European Central Bank (ECB) conducted a climate stress test that utilised extensive information from banks and other corporations, containing both past and future climate and financial data. The test aimed to encompass the various ways climate risk affects the economy and its transmission channels over the next thirty years. France: The Autorité de contrôle prudentiel et de résolution (ACPR) of Banque de France carried out a pilot exercise in 2020 related to climate related risks, wherein data was gathered from banks and insurers. It pertained to their exposure to different sectors and geographic regions. Additionally, quantitative data concerning credit and market risks, such as PD and LGD, was also collected. Italy: Banca d’Italia conducted a climate stress test using survey and other data to estimate the effects of carbon taxes on financially vulnerable firms and households. Japan: The Japan Financial Services Agency (FSA) through its climate scenario analysis collects quantitative data including sector-wise lending exposures, credit costs as well as qualitative information such as governance, management actions. Singapore: The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) analysed the macroeconomic consequences of physical risks by conducting a simulation that assessed the impact of a significant flood. This simulation drew upon the damages caused by previous flooding incidents in the Southeast Asia region for reference. United Kingdom: The Bank of England launched the Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES) in June 2021. Under the exercise, information on banks’ clients and their exposure and their plans to deal with impact under different climate scenarios was gathered. United States of America: Recently, Federal Reserve Board initiated a pilot climate scenario analysis exercise aimed at gaining insights into the climate risk management practices and challenges faced by major financial institutions. The objective of the pilot exercise is to strengthen the capacity of both major banking organizations and supervisory authorities to recognize, assess, measure, oversee, manage and mitigate financial risks associated with climate change. Source: Supervisory and Regulatory Approaches to Climate-related Risks: Final report, published by Financial Stability Board. | III. Climate Risk Drivers and Transmission Channels of Climate Risk Climate Risk Drivers Climate risk drivers can be classified into two primary categories: physical risks and transition risks. Physical risks originate from severe weather incidents like floods, cyclones, drought, and heatwaves. The physical risk drivers have the potential to cause loss of lives, damage to properties as also affect livelihood. Transition risks result from the changes in policies designed to control/ mitigate the economic/ social costs associated with transitioning to a greener economy, technological advancements, changing consumer/ investor preferences, constraints on trade policies that impact the availability and affordability of both existing and emerging technologies4. Physical risk drivers can be further categorised into two types: acute and chronic events. Acute physical risk drivers involve sudden and severe weather events, including floods, heatwaves, landslides, storms, and wildfires. Chronic physical risk drivers result from the long-term changes in climate, such as variations in precipitation, increases in sea levels, and changes in average temperatures. Transition risk drivers emerge from modifications in policies implemented by governments and regulators to transition towards a low-carbon economy, technological advancements that enable the transition, changes in consumer and market sentiment towards less carbon-intensive products or investments. In addition, greater awareness and sensitivity to climate change may raise the reputational and litigation risks for corporations and banks. Transmission Channels Transmission channels refer to the causal chains that facilitate the manifestation of climate risk drivers into the financial risks encountered by banks. The BCBS divides these transmission channels into two categories: microeconomic and macroeconomic. The microeconomic transmission channel refers to the causal pathways that connect climate risk drivers to the individual counterparties of banks, their operations, and funding capacity. It encompasses the indirect impacts on the specific financial assets that banks possess, including bonds, single-name credit default swaps, and equities. The macroeconomic transmission channels refer to the pathways through which climate risk drivers affect macro-level elements such as economic growth and labour productivity. It refers to the direct effects on macro variables like inflation, risk-free interest rates, and more. Climate risk drivers do not necessarily represent a new type of risk, and can be translated into traditional financial risk categories through transmission channels (Chart 1). For instance, the effect of a flood on the profitability of a counterparty may lead to its incapacity to repay debt, thereby creating credit risk for the bank. Climate risk drivers, particularly those transmitted through macroeconomic channels, can result in elevated credit and market risk for banks. A policy shift that causes a change in the value of assets held in a bank’s investment portfolio may result in mark-to-market losses being reported, crystallising in market risk for the bank. Climate risk drivers have the potential to cause disruption in asset correlations and alter the liquidity conditions of specific assets, undermining the assumptions underlying liquidity risk. The banks may be vulnerable to increased litigation costs stemming from climate-sensitive lending or investments. Acute physical climate risk drivers can affect the operations of bank branches, administrative offices, and data centres. Governments’ initiatives to move away from fossil fuels can have repercussions on revenues, and a bearing on their credit ratings as well as of entities linked to the sovereign. It is also believed that climate change will adversely impact labour productivity and human mortality. These socioeconomic changes could have indirect effects on the banks, influencing economic growth and ultimately affecting the creditworthiness of the borrowers.  IV. Pilot Climate Vulnerability Assessment and Stress Testing (VAST) – RBI’s Endeavour to Measure Climate-related Financial Risks Faced by Banks In 2022, a concise and targeted survey5 was undertaken among select scheduled commercial banks in India to refine the regulatory and supervisory strategies concerning climate-related financial risks and sustainable finance. Subsequently, a consultative discussion paper (DP) on climate risk and sustainable finance covering aspects such as (i) governance (ii) strategy (iii) risk management, and (iv) disclosure was issued in July 2022.6 As a follow-up to the comments received on the discussion paper in area of climate stress testing, an exercise was conducted in October-November 2022 by the Reserve Bank on pilot basis for a forward-looking assessment of the exposure, impact, and resilience of participating banks’ financial position under severe but plausible scenarios. The pilot climate VAST exercise 2022 was exploratory in nature. The objective of the exercise was to (i) assess how the climate risk could impact individual banks, (ii) develop climate scenario analysis and stress testing capabilities in the banks and within the Reserve Bank, (iii) build in-house capacity in banks for identifying, measuring, and managing climate related financial risks and (iv) to facilitate and promote dialogue with the REs about climate-related financial vulnerabilities. The intent of the exercise was neither to assess capital adequacy under stress scenarios nor to prescribe any hurdle rates in terms of minimum capital levels. The exercise adopted a hybrid approach (with certain datasets provided by the Reserve Bank to the participating banks) covering a total of fifteen banks with a mix of public sector banks, private sector banks, and foreign banks. The selected banks were amongst the largest banks in terms of asset size in their respective categories. A static7 balance sheet approach was used as a proxy for the participating banks’ extant business models. An assessment of potential loss due to different climate risk drivers under different climate scenarios, as also the vulnerability of the interest income of the banks due to the transition risk was estimated based on the financial year 2021-22 standalone audited financial statements. Given that it was a pilot exercise, data was collected for three sectors (electricity production, transport and manufacturing) and eleven sub-sectors (Chart 2) from the participating banks, which were selected based on the quantum of Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.8 Each participating bank identified top five non-financial corporate counterparties in terms of their gross fund-based exposure, in each of the aforesaid sectors and furnished the information in accordance with the requirements stipulated in the exercise. As part of the exercise, the banks furnished a mix of quantitative and qualitative data, under five schedules, to understand their exposures to financial risks arising from the climate change under different plausible future scenarios. The data provided by banks included counterparty specific data such as gross fund-based exposure as on March 31, 2022, interest income from the counterparty during the FY 2021-22, and the location of collateral/plant. The Reserve Bank provided the data on Vulnerability Factors (VF) for the chosen physical risk hazards, i.e., Flood and Cyclone, and transition risk under the chosen NGFS scenarios. Based on the VFs, the banks calculated stressed PDs and LGDs under different scenarios. The stressed PDs, and LGDs were used for estimating Credit Loss Potential (CLP). CLP calculated under the stressed scenarios was compared against the baseline CLP to estimate the impact on credit risk of the non-financial corporate counterparties (of the gross fund-based exposures) arising from physical and transition risks of the participating banks. Other risks viz. market risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, liability risk were not covered in the exercise. The data from the participating banks was sought in five Survey schedules. Details on the survey schedules are provided in the Annex.  V. Stylized Facts and Empirical Findings of Pilot Climate VAST Exercise - 2022 Stylized Facts Of the fifteen banks, only few banks reported that climate-related risk is being included in scenario analysis and stress testing (SAST) done by them, and the rest were not including climate risk in their SAST, due to issues relating to data availability, data consistency and lack of expertise. Only a few banks were including climate risk stress test framework in their Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP). Banks were generally of the view that climate stress testing exercises may not be considered for prescribing capital requirements. Banks were also of the mixed view on the adequacy of data supplied by the Reserve Bank for carrying out the pilot VAST exercise. Some banks reported that data provided were adequate while others indicated otherwise. The banks reported a number of other challenges faced by them in conducting the exercise like selection of counterparties, availability of climate emission information and modelling them to acceptable outcomes, getting corporate counterparty information on geographic location (district/ state-wise, including location of the manufacturing plants/ collateral, etc.), estimation of the potential loss key performance indicators9 (KPIs) based on the associated vulnerability factors (VFs) of physical risk and transition risk drivers faced by a corporate borrower, inadequate staff proficiency, and reluctance of their counterparties to provide necessary data. The banks generally felt that the overall ecosystem with respect to climate needs to evolve. They also highlighted the absence of borrower/ sector-specific climate-related financial risk indicators with objective, specific, monitorable and measurable metrics over the next 5-10 years in line with globally accepted Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi)10. Non-availability of climate risk-related stress testing models/ methodologies that specifically factor India’s climate goals was cited as a major challenge in integrating climate risk assessment into banks’ stress testing framework. Findings of the Pilot Climate VAST Exercise - 2022 Under the exercise, the assessment of short-term physical risk included estimation of the impact of counterparties’ exposure to extreme weather events, viz., floods and cyclones on banks’ credit risk. The impact on the banks’ credit loss potential on consolidated basis due to floods and cyclones was assumed to be nil under the baseline scenario. The impact on credit loss potential of banks due to flood was projected to increase by 66.1 per cent. Similarly, the impact on credit loss potential of banks due to cyclone was projected to increase by 65.8 per cent. Under the tail risk event in the short-term scenario, participating banks’ credit loss potential was projected to increase by 138.0 per cent as against the baseline scenario. The impact on credit risk of banks due to the long-term impact of transition risk was assessed under three scenarios and the increase in credit loss potential of banks at three time-intervals in year 2030, 2040 and 2050 was measured. Under the Below 2°C (orderly) scenario, credit loss potential of banks was observed to increase by 106 per cent in 2030, 109 per cent in 2040, and 107 per cent in 2050 as against the baseline scenario. Under the divergent net zero (disorderly) scenario, credit loss potential of banks was observed to increase by 110 per cent in 2030, 130 per cent in 2040, and 146 per cent in 2050 as against the baseline scenario. Under the nationally determined contributions (hot house world) scenario, credit loss potential of banks was observed to increase by 103 per cent in 2030, 98 percent in 2040, and 92 percent in 2050 as against the baseline scenario. VI. Way Forward The exercise, being exploratory in nature, covered only select REs and sectors with limited scope. Only two physical risk events, viz., flood and cyclone were considered out of the thirteen climate-events identified by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India. Going forward, the Climate VAST exercises may build upon the findings of the pilot exercise to include other REs too with a larger base of counterparties, other plausible climate scenarios and sectors (such as household, commercial, agriculture, sovereign etc.) based on the economic activity with the aim of enhancing the banks’ capacity to evaluate and manage climate risk. Globally, most of the work on climate stress testing is restricted to credit risk and therefore, this pilot exercise also focussed on assessing on the credit risk the impact of climate-related risk drivers. Drawing from the learnings of successive stress test iterations, future exercise may cover other risks faced by the banks such as market, operational, liquidity, and litigation risks. Due to the data and capacity challenges, banks faced difficulties in modelling the forward-looking KPIs in pilot Climate VAST exercise. The KPIs were determined based on the Judgmental Forecasting methods as also discussions with the concerned counterparty. However, in future, banks may need to construct and employ statistical models to calculate the forward-looking KPIs for the climate-related financial risks. Climate scenario analysis and stress testing initiatives are in an embryonic phase, owing to the intricacies involved in the scenario analysis and modelling of climate hazards, as well as the dearth of requisite data. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the banks and other stakeholders concur that such initiatives should continue to be refined, and periodically refreshed in order to identify, assess, measure, monitor and manage the climate-related financial risks, and to facilitate informed policymaking in the years ahead. Thus, there is a consensus that such coordinated efforts by the RBI, banks and their counterparties would go a long way in combating the challenge faced due to climate change. In this context, it is worth remembering the words of Mahatma Gandhi: “You may never know what results come of your actions, but if you do nothing, there will be no result.” References Bank for International Settlements. (2020). “The green swan - Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change.” Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2021). “Climate-related risk drivers and their transmission channels.” Federal Reserve Board. (2022). “Federal Reserve Board announces that six of the nation’s largest banks will participate in a pilot climate scenario analysis exercise designed to enhance the ability of supervisors and firms to measure and manage climate-related financial risks [Press release].” Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2022). “Supervisory and Regulatory Approaches to Climate-related Risks.” Gosling, S., Zaherpour, J., & Ibarreta Ruiz, D. (2018). “PESETA III: Climate change impacts on labour productivity”. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. MoEFCC. (2021). “India: Third Biennial Update Report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.” Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). (2020). “Overview of Environmental Risk Analysis by Financial Institutions.” Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). (2021). “NGFS Climate Scenarios for central banks and supervisors.” Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). (2021). “Implementing the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures.” World Economic Forum (WEF). (2023). “The Global Risks Report 2023.” World Health Organization. (2021). “Climate change and health. Fact sheet.” Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

Annex Schedule 1 was a survey to capture qualitative information on the participating banks’ existing climate-related financial risk stress testing framework, climate-related financial risk management and modelling methods employed by the banks. Schedule 2 contained quantitative metrics to capture (a) the GHG emission footprint of the portfolio as regards the identified sectors and (b) the sensitivity of banks’ interest income to the transition risk, and the concentration of the GHG sensitive assets. The sector-wise GHG Emissions Intensity Factor (EI Factors) were provided by RBI which were estimated on the basis of data from Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change (MoEFCC) and the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), Government of India. The banks used these EI Factors to calculate the GHG emission transition sensitivity factors (TSFs) and the vulnerability of their interest income (VII) in respect of each corporate counterparty. Schedule 3 assessed credit risk in the short term. The assessment was done on account of acute physical risk drivers, viz., floods and cyclones over a one-year time horizon. It also included tail risk assessment under a Green Swan11 event arising out of disorderly transition risk drivers. The schedule provided quantitative inputs on the impact of physical/ transition risks on the credit portfolio of the participating banks. • For physical risks, Vulnerability Factors (VFs) were constructed based on the events, viz., floods/ cyclones and the economic losses caused by these events in about 50 years for each district. These VFs were constructed based on location of the corporate counterparty and the collateral using the datasets published by the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) and Ministry of Jal Shakti (MoJS), Government of India for each of the districts. The VFs were in turn provided to the banks for estimating the loss in total income of the counterparty as also the loss in the realizable value of the collateral. The banks estimated the potential loss key performance indicators (KPIs) vis-à-vis the baseline scenarios. • The assessment of credit risk on account of transition risk drivers for tail risk was done in respect of a Green Swan event arising out of disorderly transition risk. These disorderly transition shocks could affect banks through their credit exposures to the GHG sensitive sectors. The disorderly transition scenario, developed by Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) were used, which envisioned that the delayed policy measures to reduce GHG emissions led to sudden and unanticipated increase in GHG emission prices in 2030 to achieve the Paris Agreement targets. However, in the pilot exercise, it was assumed that the increase in the GHG emission prices would commence in April 2022 and not in 2030 to assess the tail risks in the participating banks’ current balance sheets over a five-year period. The banks estimated the potential loss in KPIs vis-à-vis the baseline scenarios for which the relevant macroeconomic and macro-financial parameters were provided to them. Schedule 4 envisioned that some climate-related financial risks would materialise within a bank’s traditional three-to-five-year capital planning horizon while other climate-related financial risks would materialise over longer time horizon. It was thus used to assess the credit risks on account of transition risk drivers in a longer-time horizon covering three NGFS scenarios (viz. Below 2oC, Divergent Net Zero, and Nationally Determined Contributions) with a longer time horizon (up to 2050). The relevant temporal macroeconomic and macro-financial parameters (for different future year-points up to 2050) were provided to the banks for estimating the KPIs under the three NGFS scenarios vis-à-vis the baseline scenarios. Schedule 5 required the participating banks to select any one corporate counterparty from any of the identified sectors and carry out their analysis and furnish results in a free style manner. The information that could be provided included the National Industrial Classification - 2008, asset type, gross exposure, duration of exposure, major risks faced by the selected counterparty (transition risks or physical risks including the specific physical hazard to which it was exposed). The information to be covered also include as to how the counterparty would adapt to the climate risks or mitigate them, location of the exposures, location of collateral, banks’ views as to how the corporate counterparty’s KPIs were expected to evolve under each scenario and projected periods. |

|