Acknowledgements The Committee would like to thank the representatives of Asset Reconstruction Company (India) Limited along with its sponsor i.e. Avenue India Resurgence Pte. Limited, Edelweiss Asset Reconstruction Company Limited, JM Financial Asset Reconstruction Company Limited, Assets Care & Reconstruction Enterprise Limited along with its sponsor ARES SSG Capital Management (Singapore) Pte. Limited, Lone Star India Asset Reconstruction Private Limited, ANA ARC Private Limited, State Bank of India, Indian Overseas Bank, IDBI Bank, Bank of Baroda, Yes Bank Limited, Axis Bank Limited, ICICI Bank Limited, Kotak Investment Advisors Limited and Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co. for their valuable inputs and suggestions. The Committee would also like to thank the representatives of CRISIL Ratings Limited, ICRA Limited and Acuite Ratings & Research Limited for their suggestions and perspectives on the issues covered under the Committee’s remit. The Committee acknowledges its gratitude to the representatives from law firms, viz. AZB & Partners, Juris Corp and Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas as well as the audit firms, viz. BSR & Co. LLP and S R Batliboi & Co. LLP for their excellent presentations. The Committee also places on record its appreciation for the valuable inputs received during the discussions held with the representatives of various industry associations/organisations, viz. Indian Banks’ Association, Finance Industry Development Council, Association of ARCs in India, Confederation of Indian Industry, Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India and Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry. The Committee acknowledges, with thanks, the views/ suggestions received from various other ARCs, market participants and other stakeholders, through public domain/email. Finally, the Committee would also like to convey its deep appreciation for the excellent support provided by the Committee’s secretariat, comprising of Shri J P Sharma, Chief General Manager, Ms. Veena Srivastava, General Manager and Shri Parimal Kumar Shivendu, Assistant General Manager, in drafting the Committee’s report, promptly responding to the complex information and analytical requirements of the Committee, and efficiently coordinating the meetings, which greatly facilitated the work of the Committee.

Abbreviations List of Abbreviations used in the Report | AIF | Alternative Investment Fund | | AMC | Asset Management Company | | ARC | Asset Reconstruction Company | | AUM | Assets Under Management | | BIFR | Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction | | BR Act | Banking Regulation Act, 1949 | | CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate | | CERSAI | Central Registry of Securitisation Asset Reconstruction and Security Interest of India | | CIRP | Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process | | CoC | Committee of Creditors | | CRAR | Capital to Risk-weighted Assets Ratio | | DRT | Debt Recovery Tribunal | | GNPA | Gross Non-Performing Asset | | GoI | Government of India | | FDI | Foreign Direct Investment | | FI | Financial Institution | | FPI | Foreign Portfolio Investor | | FY | Financial Year | | IBA | Indian Banks’ Association | | IBC | Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 | | IRACP | Income Recognition, Asset Classification and Provisioning | | IRR | Internal Rate of Return | | KAMCO | Korea Asset Management Corporation | | MF | Mutual Fund | | NAMA | National Asset Management Agency, Ireland | | NeSL | National E-Governance Services Limited | | NAV | Net Asset Value | | NBFC | Non-Banking Financial Company | | NCLT | National Company Law Tribunal | | NOF | Net Owned Fund | | NPA | Non-Performing Asset | | NPV | Net Present Value | | OF | Owned Fund | | PSB | Public Sector Bank | | QB | Qualified Buyer | | RA | Resolution Applicant | | RBI | Reserve Bank of India | | RDDBFI Act | Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act,1993 | | RoC | Registrar of Companies | | S4A | Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets | | SAREB | Sociedad de Gestión de Activos procedentes de la Reestructuración Bancaria, Spain | | The Act | Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 2002 | | SCB | Scheduled Commercial Bank | | SEBI | Securities and Exchange Board of India | | SICA | Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 | | SLMA | Secondary Loan Market Association | | SMA | Special Mention Account | | SR | Security Receipt |

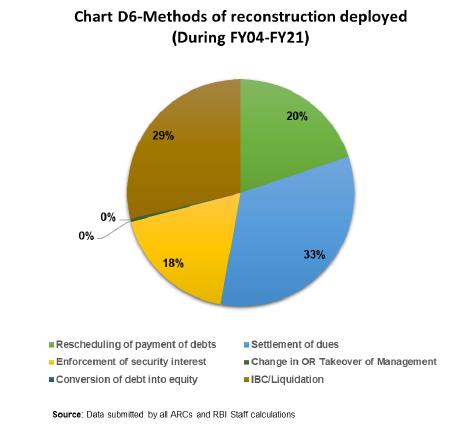

Executive Summary 1. Background 1.1. Against the backdrop of significant build-up of non-performing assets (NPAs) in the financial system, asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) are expected to play a critical role. The ARC framework is designed to allow originators to focus on their core function of lending, by removing sticky stressed financial assets from their books. ARCs act as the primary agent for recovery upon acquisition of such financial assets. The ARC framework is also designed to help borrowers revive their businesses, which protects the viable and productive assets of the economy and often ensures a better return to banks/ financial institutions (FIs), collectively referred to as ‘lenders’, from their stressed assets. 1.2. Data shows that the performance of the ARCs has been lacklustre, both in terms of ensuring recovery and revival of businesses. Banks and other investors could recover only about 14.29% of the amount owed by borrowers in respect of stressed assets sold to ARCs during the FY 2004 - FY 2013 period. Similarly, data shows that approximately 80% of the recovery made by ARCs has come through deployment of measures of reconstruction that do not necessarily lead to revival of businesses. 1.3. There are multiple factors behind the sub-optimal performance of the ARC Sector. These primarily include vintage NPAs being passed on to ARCs, lack of debt aggregation, non-availability of additional funding for stressed borrowers, difficulty in raising of funds by the ARCs on their balance sheet, etc. Also, ARCs have lacked focus on both recovery and acquiring necessary skill sets for holistic resolution of distressed borrowers. 1.4. Considering the challenges impacting the performance of the ARC Sector, the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies was constituted to undertake a comprehensive review of the working of ARCs. The terms of reference of the Committee were as under: (i) Review of existing legal and regulatory framework applicable to ARCs and recommend measures to improve efficacy of ARCs; (ii) Review of role of ARCs in resolution of stressed assets including under Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016; (iii) Suggestions for improving liquidity in and trading of security receipts; (iv) Review of business models of the ARCs; (v) Any other matter relevant to the functioning, transparency and governance of ARCs. 2. Approach/ Methodology adopted by the Committee The Committee extensively deliberated upon the matters under its remit. It held twenty-five meetings for this purpose, details of which are given in Annex I. The Committee met with various stakeholders to gain insight into the challenges faced by the ARC sector. Further, the Committee also invited1 views/ suggestions from market participants and other stakeholders. 3. Findings and Recommendations of the Committee 3.1. The Committee’s findings and recommendations cover all significant areas of functioning of ARCs. The recommendations particularly focus on matters related to acquisition, securitisation and reconstruction of financial assets and liquidity and trading of security receipts. Other areas of importance where the Committee has made recommendations include matters of governance and transparency, minimum Net Owned Fund (NOF) requirement, legal issues of significance and a few taxation issues. These recommendations are interlinked and interdependent and hence need to be examined in a holistic manner. While a summary of all recommendations made by the Committee is given in Chapter G, the following paragraphs highlight some of the key recommendations. 3.2. In the area of acquisition and securitisation of financial assets, the Committee argues for sale of stressed assets by lenders at an earlier stage to allow for optimal recovery by ARCs. In this respect, the Committee highlights the need for regulatory clarification on sale of all categories of special mention accounts (SMAs) to ARCs. Further, as a measure to incentivise lenders to sell their financial assets to ARCs at an early stage of stress, the Committee recommends a dispensation to lenders, on an ongoing basis, to amortise the loss on sale, if any, over a period of two years. To optimise upside value realisation by lenders, the Committee also recommends a higher threshold of investment in SRs by lenders below which provisioning on SRs held by them may be done on the basis of Net Asset Value (NAV) declared by the ARC instead of the IRACP norms. Further, to streamline the process of sale of stressed assets to ARCs, the Committee recommends that for accounts of Rs.100 crore2 and above, which are in default, the lender’s resolution plan should explicitly evaluate sale/ auction of such accounts to ARCs as one of the options. In case of these NPAs which are (i) more than two years old and (ii) no active resolution plan is in place and are not included in the list of NPAs identified for sale, the reason for their exclusion from the list of NPAs identified for sale should be documented. (Para D.1.7 to D.1.9 ibid) 3.3. Recognising the need of transparency and uniformity of processes in sale of stressed assets to ARCs, the Committee feels that an online platform may be created for sale of stressed assets. Infrastructure created by the Secondary Loan Market Association (SLMA) may be utilised for this purpose. Further, considering the critical role played by the reserve price in ensuring true price discovery in auctions conducted for sale of stressed assets, the Committee recommends that for all accounts above Rs.500 crore, two bank-approved external valuers should carry out a valuation to determine the liquidation value and fair market value and for accounts between Rs.100 crore to Rs.500 crore, one valuer may be engaged. Also, the final approval of the reserve price should be given by a high-level committee that has the power to approve the corresponding write-off of the loan. (Para D.1.13 to D.1.14 ibid) 3.4. In the interest of debt aggregation, the Committee recommends that the scope of Section 5 of the SARFAESI Act, and other related provisions, may be expanded to allow ARCs to acquire ‘financial assets’ as defined in the Act, for the purpose of reconstruction, not only from banks and ‘financial institutions’ but also from such entities as may be notified by the Reserve Bank. Under these proposed powers, Reserve Bank may consider permitting ARCs to acquire financial assets from all regulated entities, including AIFs, FPIs, AMCs making investment on behalf of MFs and all NBFCs (including HFCs) irrespective of asset size and from retail investors. (Para D.1.15 ibid) 3.5. The Committee understands that providing additional funding to the stressed borrowers is a key requirement for reviving their businesses. Therefore, the Committee recommends that ARCs should be allowed to sponsor SEBI registered AIFs with the objective of using these entities as an additional vehicle for facilitating restructuring/ recovery of the debt acquired by them. (Para D.2.3 to D.2.5 ibid) 3.6. One of the main obstacles faced by ARCs in effecting reconstruction of stressed assets is lack of debt aggregation. In this regard, the Committee recommends that if 66% of lenders (by value) decide to accept an offer by an ARC, the same may be binding on the remaining lenders and it must be implemented within 60 days of approval by majority lenders (66%). 100% provisioning on the loan outstanding should be mandated if a lender fails to comply with this requirement. Given that the debt aggregation is typically a time-consuming process, the Committee also recommends that the planning period be elongated to one year from the existing six months. The Committee also recommends that in cases where ARCs have acquired 66% of debt of a borrower, the Act should provide for two years of moratorium on proceedings against the borrower by other authorities. The Act should also provide that Government dues including revenues, taxes, cesses and rates due to the Central Government, State Government or local authority will be deferred in such cases. (Para D.2.6 to D.2.9 ibid) 3.7. The Committee recognises that in the interest of better value realization for originators and enhancing the effectiveness of ARCs in recovery, even the equity pertaining to a borrower company may be allowed to be sold by lenders to ARCs which have acquired the borrower’s debt. The Committee recommends that ARCs may be allowed to participate in the IBC process as a Resolution Applicant either through a SR trust or through the AIF sponsored by them. (Para D.2.10 to D.2.11 ibid) 3.8. The Committee recognises that listing and trading of SRs will take off only if ARCs’ ability to resolve the underlying stressed assets is strengthened to generate higher quantum of redemption and upside for investors. To this end, the Committee has made several key recommendations as mentioned above. Further, in the interest of giving impetus to listing and trading of SRs, the Committee recommends that the list of eligible qualified buyers may be further expanded to include HNIs with minimum investment of Rs.1 crore, corporates (Net Worth-Rs.10 crore & above), all NBFCs/HFCs, trusts, family offices, pension funds and distressed asset funds with the condition that (a) defaulting promoters should not be gaining access to secured assets through SRs and (b) corporates cannot invest in SRs issued by ARCs which are related parties as per SEBI definition. (Para E.1 to E.3 ibid) 3.9. The Committee also underscores that the need for protecting the interest of investors and investing lenders (for which the requirement of ‘skin in the game’, i.e., minimum investment of 15% is prescribed for the ARCs), should be weighed against the need for distribution of risk among the willing investors. Therefore, it recommends that for all transactions, per SR class/ scheme, the minimum investment in SRs by an ARC should be 15% of the lenders’ investment in SRs or 2.5% of the total SRs issued, whichever is higher. (Para E.4 ibid) 3.10. Considering the wider role envisaged for ARCs as the prime vehicle for resolution of stressed assets of the economy, the Committee recommends that the minimum NOF requirement for ARCs should be increased to Rs.200 crore wherein existing ARCs may be provided a glide path to meet this requirement. (Para F.1.1 ibid) 3.11. Recognising the critical role of Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) in the valuation of SRs and, therefore, the need for continuity in engagement of CRAs, the Committee recommends that ARCs must retain a CRA for at least 3 years. In case of change of a CRA, both parties must disclose the reason for such change. (Para F.2.2 ibid) 3.12. Due to information asymmetry, foreign investors appear to draw comfort if the documents are standardised in some manner with embedded investor protection features. Therefore, the Committee recommends that the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA) may review the standard Assignment Agreement and Trust Deed and update the same to reflect the changes and expectations of the investors. SLMA may also be appropriately engaged for standardisation of these documents. Further, the document (Offer Document or Prospectus as the case may be) for soliciting investment in SRs and its subsequent updates, if any, should indicate at least the track record of the ARC for at least 10 years. The track record should, inter alia, have information on return, rating migration and rating agency of past schemes. (Para E.5 and F.2.4 ibid) 3.13. In the interest of operational efficiency, the Committee recommends that the avenues for deployment of surplus funds on the ARC’s balance sheet may be widened to include a variety of short-term instruments as the currently restricted investment opportunities generate low return for ARCs and result in overall inefficient cash management. Further, in order to allow ARCs to raise additional equity from strategic and foreign sources and attract more capital to the sector without additional regulatory burden, the Committee recommends that the threshold of shareholding for recognising a sponsor should be increased to 20% from the existing 10% with suitable safeguards. (Para F.3.1 to F.3.2 ibid) 3.14. To make enforcement of security interest under the Act more efficient, the Committee recommends that the definition of ‘secured creditor’ in the Act be expanded to include the acquirer of a financial asset (e.g., ARC) in whose favour security interest is assigned, even if the enforcement rights under the Act were not available with the assignor. (Para F.4.1 ibid) 3.15. In the matter related to taxation of income generated from investment in SRs issued by ARCs, the possibility of a ‘pass-through’ regime for AIF investors may be looked into by Central Board of Direct Taxes(CBDT). The Committee also recommends that CBDT may consider clarifying on the tax rate applicable to FPIs. (Para F.5.1 to F.5.2 ibid) 3.16. This Report is divided into seven chapters. Chapter A profiles the ARC sector and the terms of reference of the Committee. Chapter B records the genesis of the ARC sector and briefly analyses design aspects of its international counterparts. Chapter C describes the regulatory and legal framework under which ARCs operate. Chapter D analyses and makes recommendations on the acquisition, securitisation and asset reconstruction aspects of ARC business. Chapter E is dedicated to analysing and recommending measures for stimulation of trading and listing of security receipts. Chapter F covers various other issues pertaining to the ARC sector. The final chapter summarises the Committee’s recommendations with appropriate action indicators.

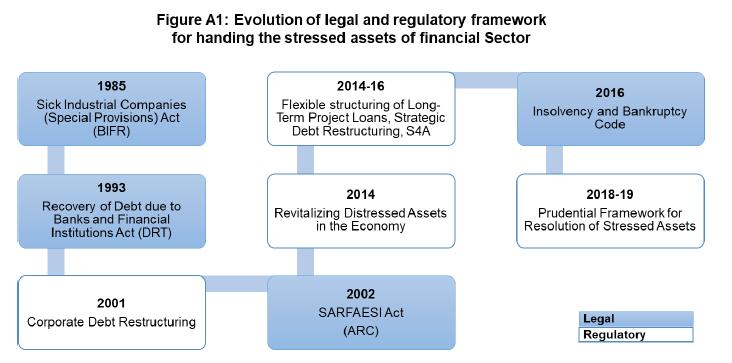

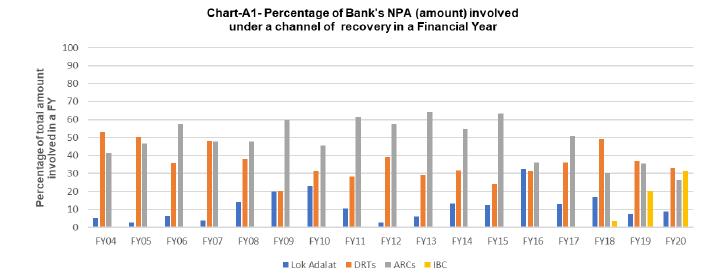

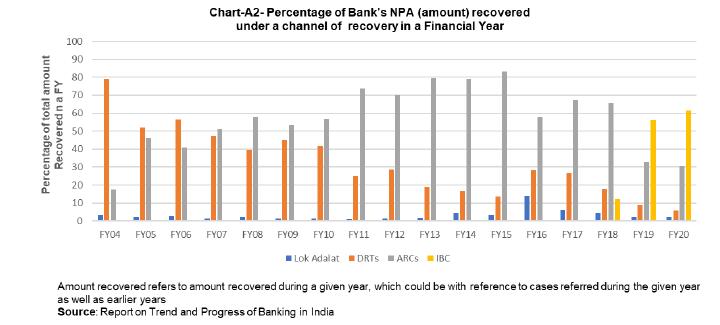

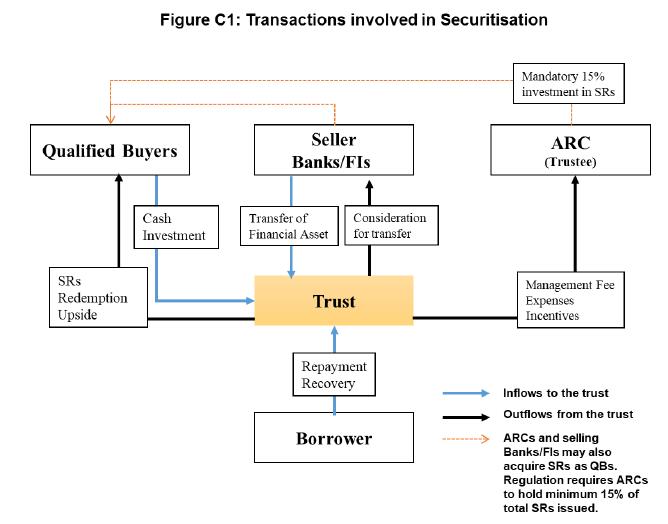

Chapter A. Introduction A.1. A sound banking system is an essential requirement for maintaining financial stability in any country. One of the parameters of soundness is the level of non-performing assets (NPAs) in the banking system. In this context, it is common knowledge that the Indian banking system has often been saddled with high levels of NPAs which has been affecting the profitability and eventually the capital position of banks, especially the public sector banks (PSBs). This has been one of the factors which has led to some level of risk aversion among the banks and thereby deceleration of credit growth in the country in the recent years. The level of gross NPAs (GNPAs) of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) stood at 7.5% at the end of March 2021. The Financial Stability Report of July 2021 published by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) indicates that the GNPA ratio of SCBs may transition to 9.80% in the baseline scenario by March 2022 and may increase to 10.36% and 11.22% under the other stress scenarios. Such a high level of NPAs in the economy can further decelerate growth of credit in the economy and can potentially undermine the stability of the financial system. A.2. In view of its importance for the health of the banking system, management of NPAs has been attracting attention from the RBI and the Government for quite some time now. A chronological evolution of important legal and regulatory frameworks for handling of stressed assets is given in the Figure A1 below. The first such significant legal framework to manage the stress in the banking system was the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 (SICA). It was enacted for timely detection of sickness in industrial units and to undertake speedy action to resolve the insolvency of sick units through a Board of experts, namely the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR). SICA failed to meet its objective due to delays caused by legal suits and lack of timely decisions by the stakeholders and, therefore, was finally repealed in the year 2003. Related provisions of this Act were added in the Companies Act, 2013 and the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) took over the functions of BIFR. Insolvency resolution frameworks as a tool for handling stressed assets culminated into the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC). IBC was enacted as a single code to consolidate the existing frameworks for insolvency and bankruptcy and has emerged as a significant tool for recovery. A.3. Other noteworthy legislations which aimed to facilitate recovery of debt for banks and Financial Institutions include the Recovery of Debt due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 (RDDBFI Act) and the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 2002. The former Act attempts to provide speedy recovery through tribunals, namely, Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) whereas the latter allows secured creditors to enforce their security interest without the intervention of the courts. The Act also led to creation of asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) as a permanent institutional arrangement to handle the stressed financial assets of banks and other financial institutions.  A.4. RBI has been providing regulatory frameworks to banks for efficient handling of stressed assets in their books. The Corporate Debt Restructuring framework envisaged vide circular dated August 23, 2001 provided a mechanism for timely and transparent restructuring of debt of viable entities, outside the purview of BIFR, DRT and other legal proceedings. This framework aimed at preserving viable corporates and minimizing losses to the creditors through an orderly and coordinated restructuring programme. Another major regulatory intervention was the “Framework for Revitalising Distressed Assets in the Economy” dated January 30, 2014. This framework attempted to centralise reporting and dissemination of information on large credit, incentivise lenders to agree collectively and quickly to a restructuring plan, provide improvements in restructuring process, etc. This was followed by various schemes of restructuring prescribed by RBI, namely, Flexible Structuring of Long Term Project Loans, Strategic Debt Restructuring Scheme, Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A), etc. Owing to the mixed success of these schemes, RBI issued a new set of guidelines vide the “Prudential Framework for Resolution of Stressed Assets” dated June 7, 2019. The new guidelines provide a framework for early recognition, reporting and time bound resolution of stressed assets and withdraw the aforementioned frameworks and schemes. A.5. Charts A1 and A2 below depict the use of various channels by banks for recovery of their NPAs. Data indicates that after their introduction in 2003, ARCs have been a major channel of recovery for banks until FY19. In FY20, however, banks took more NPAs for resolution through IBC compared to the ARC channel. Data also suggests that from FY19 onwards, recovery through IBC has been greater than the recovery through ARCs (Chart A2).   A.6. Preference given to ARCs by banks is largely on account of three fundamental needs that ARCs are able to fulfil. First, ARCs allow banks/ FIs to focus on their core function of lending by removing the sticky stressed assets from their books and thereby freeing up their capital and management for productive use. Second, where lenders invest in security receipts (SRs), ARCs make recovery for lenders by acting as the manager of the stressed assets. Third, ARCs can help the borrowers in reviving their businesses. Revival of businesses is a significant need both for protecting the viable and productive assets of the economy and for ensuring better return to lenders from their stressed assets. A.7. The recent trend of shift towards IBC is primarily driven by two factors. First, IBC promises both time-bound and optimal recovery for creditors as well as insolvency resolution of the borrowers in an intertwined manner. The other factor for this shift may be the lacklustre performance of the ARC sector, both in terms of ensuring recovery and reviving businesses. A.8. As on date, there are 28 ARCs in operation. The AUM of the top five ARCs (as on March 31, 2021) constitute 70% of total AUM of all the ARCs in terms of book value acquired. Further, only three ARCs have net owned fund (NOF) above Rs.1500 crore. Furthermore, in terms of the capital base of the sector, over 54% is held by the top three ARCs; the corresponding share is 62% for the top five ARCs. While ARCs have been in operation since 2003, their performance in management of stressed assets of banks/ FIs is still uneven on several parameters. A.9. Overall recovery made by the ARC sector during the period FY04 to FY133 was 68.6% when measured in terms of redemption of SRs as a percentage of total SRs issued. However, the same comes down to 14.29% when the redemption is measured in terms of the book value of the assets acquired. Please refer to Table D1 on status of SRs for detailed breakup. Similarly, ARCs’ performance in ensuring revival of businesses has also been poor. The data indicates that approximately 80% of the recovery for the sector, so far, has come through deployment of methods of reconstruction that do not necessarily lead to revival of business. ARCs have rarely used methods such as change in or takeover of the management of the business of the borrower or conversion of debt into equity in a borrower’s company. Rescheduling of payment of debts was also involved only in 19.9% of the recovery made by ARCs. A.10. The overall performance of ARC Sector has left much to be desired. However, it would be incorrect to assume that the problems of ARC sector are entirely of its own making. In fact, the ageing of NPAs before their sale may be contributing to poor recovery. This gets further aggravated by lack of debt aggregation. Revival of stressed business typically requires additional funding which is difficult to come by for old NPAs. Inadequate capital at ARC level and the regulatory prescription limiting the extent of funds that could be raised, from external investors through securitization, seems to have made ARCs’ attempt at revival of businesses even more difficult. ARCs’ lack of skill sets in turning around borrowers cannot be ignored. A.11. Despite the reshaping of the ecosystem available for lenders for handling of stressed assets and the ARC sector’s sub-optimal performance and its challenges, the ARC model remains relevant as a private sector led permanent institutional framework for out-of-court resolution of stressed assets of the financial sector. Also, the ARC model, uniquely, allows investors to hold on to the upside of stressed assets in uncertain times through issuance of security receipts. However, for the model to remain sustainable, ARCs need to focus on turning around borrowers and not merely making recoveries. ARCs also need to acquire differentiated skill sets, and resources vis-à-vis the selling lenders in resolving stressed assets. Such empowered ARCs would better serve the needs of the financial sector and economy in general. A.12. It was in this context that the Committee was constituted to undertake a comprehensive review of the working of ARCs and to recommend suitable measures enabling ARCs meet the growing requirements of the financial sector. The terms of reference of the Committee were as under: (a) Review of existing legal and regulatory framework applicable to ARCs and recommend measures to improve efficacy of ARCs; (b) Review of role of ARCs in resolution of stressed assets including under Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016; (c) Suggestions for improving liquidity in and trading of security receipts; (d) Review of business models of the ARCs; (e) Any other matter relevant to the functioning, transparency and governance of ARCs. A.13. The Committee held twenty-five meetings to extensively deliberate on the matters under its remit. Details of the meetings are given in Annex I. During these meetings, the Committee met with various stakeholders including banks, ARCs, industry bodies, law firms, auditors and credit rating agencies to understand the challenges faced by the ARC sector and sought their suggestions for overcoming those challenges. Further, the Committee also invited views/suggestions from market participants and other stakeholders. Chapter B. Genesis of ARCs in India and International Experience Genesis of ARCs in India B.1. The Committee on Banking Sector Reforms of 1991 (Narasimham Committee I) had envisaged an asset management company (AMC) like structure, namely an Asset Reconstruction Fund (ARF) to address the NPA crisis of that time. The ARF was to take over bad and doubtful assets off the balance sheets of banks and FIs and allow lenders to recycle their funds and direct the same into generating new productive assets. The ARF was to be provided with broader powers for recovery and was proposed to be funded by Government of India, RBI, PSBs and financial institutions. However, the recommendation was not implemented. B.2. The current form of the ARC Model finds its root in one of the recommendations of the Committee on Banking Sector Reforms of 1998 (Narasimham Committee II). The Committee, while expecting that a combination of policy and institutional development would lower the level of new NPAs, emphasized the need for addressing the problem of the huge backlog of NPAs. The Committee held that financial restructuring in the form of hiving off the NPA portfolio from the books of the banks would play a major role in strengthening of the banks. The Committee therefore suggested that all loan assets in the doubtful and loss categories could be transferred to an ARC which would issue to the banks ‘NPA Swap Bonds’ representing the realizable value of the assets transferred. The Committee recommended that an ARC could be set up by one bank or a set of banks or even in the private sector. Funding of such an ARC could be facilitated by treating it on par with venture capital for the purpose of tax incentives. The Committee also recognized that some banks may be willing to fund such assets, in effect, by securitising them. It also recommended that to enable the ARC to effect recoveries, it may be allowed access to DRTs. The committee noted that these approaches should be backed by changes in the legal system as well. B.3. Another important committee involved in shaping the current form of the ARC model was the Expert Committee for Recommending Changes in the Legal Framework concerning Banking System (Andhyarujina Committee) (1999-2000) which, inter alia, had recommended a legal framework for securitisation. The Committee recognised that securitisation as a product provides many benefits to the originator, the investor and the financial system in general. The Committee had examined each stage of securitisation, viz., the transfer or assignment or vesting or transmission of financial assets, the form and the nature of special purpose vehicles, the issue of transferable receipts, and enunciated the legal initiatives required. The current framework of securitisation under the SARFAESI Act is based on the Committee’s draft Securitisation Bill. B.4. The Government of India enacted the SARFAESI Act in 2002 and paved the way for setting up ARCs in India. The Act envisaged that ARCs would be registered and regulated by RBI. Accordingly, initial guidelines were issued by RBI in April 2003. The first ARC, namely, Asset Reconstruction Company (India) Limited, was also registered in 2003. As on date, there are 28 ARCs in operation. As on March 31, 2021, the cumulative AUM of the Sector stood at approximately Rs.5.2 lakh crore in terms of book value acquired and the cumulative capital at play, as measured in terms of NOF, of the Sector stood at approximately Rs.9.8 thousand crore. International Experience B.5. In the Indian context, ARCs mainly act as a private-sector led permanent institutional arrangement for handling of stressed assets. The world over, typically, stressed asset AMCs have been set up to play a similar role, though for a limited period. These AMCs are entities to which stressed assets are transferred from either for recovering their value (either through profit maximisation or loss minimisation) or for warehousing (insulating them from the market fluctuations, until market conditions normalise). These AMCs have been critical in resolution of stressed assets, especially in the wake of a financial crisis. Globally, AMCs typically are temporary entities and they generally do not keep the stressed assets in their own books for resolution. AMCs usually sell off the stressed assets to third party investors. On the other hand, ARCs in India not only take stressed assets in their books but even when they securitise it they remain solely responsible for resolution of the stressed assets. Like ARCs, AMCs also help revive credit expansion, preserve financial stability and help build a liquid market for stressed assets. The ARC mechanism also provides an alternate investment (with diversification benefit) opportunity for investors through securitisation. B.6. Fundamentally, the design of these specialised institutions has been influenced by the nature and extent of the crisis faced by a country. However, there are some general key design principles, pertaining to ownership of AMCs, method of transfer of stressed assets, sourcing and valuation of stressed assets, etc., that underlie the international AMCs. A closer look at these principles may be useful in improving the current design of ARCs. A brief snapshot of the same is as follows: (a) Ownership – There are various models of ownership across the world. Under these models, the ownership could be public, private or public-private partnership (PPP). The ‘transfer price’ (price at which NPAs are transferred to the AMC) plays a critical role in deciding whether an AMC is floated as a public or private entity. Setting up a private AMC implies that the ‘transfer price’ will be the ‘market price’ of the NPA. This in turn means banks may take large haircuts and thus will be recognising the loss upfront and thereby adversely impacting their level of capital. SAREB AMC in Spain was established in 2012 as a private for-profit company. Setting up a public AMC would give the flexibility to have a ‘transfer price’ above the economic value of an NPA. It will however mean that the AMCs pays an excessive price for the stressed asset, eventually leading to loss for the AMC. It will help banks avoid upfront losses and depletion of capital but at the cost of masking their weakness. KAMCO in Korea and Danaharta in Malaysia are examples of public AMCs. A similar trade-off also exists when AMCs are planned under the PPP model where a compromise between upfront provision of capital to banks and accepting eventual losses to AMC is made by the authorities. NAMA in Ireland set up in 2009 had an ownership that was private/public hybrid. (b) Sourcing of NPA – Centralised AMCs are set up when the NPAs arise due to systemic problems. In such a case it is also highly likely that a public AMC is set up as the private sector may not have the financial wherewithal or coordination capability to mop up system wide NPAs, especially at the time of heightened stress. Centralised AMCs give the benefit of consistency in workout practices and may have greater bargaining power to drive any legal changes that may be required for speedy loan recovery. KAMCO in Korea and Danaharta in Malaysia were centralised AMCs. Bank-specific AMCs are set up when NPA issues are limited to a few individual banks. An example of a bank-specific AMC framework is Sweden where Securum and Retrieva were established in 1992 to work out the NPAs of Nordbanken and Gota Bank, respectively. (c) Voluntary vs mandatory transfer – In order to counter the reluctance of banks to recognize losses upfront while dealing with a systemic NPA problem, the option of mandatory transfer to AMC is used. SAREB AMC in Spain used mandatory transfer. In other scenarios, voluntary transfer is used, especially if not all banks are affected by NPA problems. Voluntary transfer allows for a level playing field across banks so that banks transferring bad assets to the AMC do not gain an unfair advantage over the others, by strengthening their balance sheets more than their peers. (d) Valuing of NPA in the books of AMC – When AMCs are used for warehousing of the assets, an important consideration is how to account for the assets acquired. If these are valued at fair value, short-term mark-to-market price variations can adversely affect their value, defeating one of the objectives of putting these in AMCs. On the other hand, keeping the assets at book value can reduce the AMC’s incentive to dispose them off and, hence, unduly prolong the life of the asset. B.7. Naturally, the varied design possibilities imply that the performance of an AMC/ARC like entity can be judged only against the objective for which it has been established. However, international experience suggests that the performance generally depends on the operational independence, adequacy of resources, technical competence and the type and quality of assets these specialised institutions acquire. In this respect, the technical competence of these entities becomes extremely important. Typically, these specialised institutions acquire bad assets which the originators had failed to keep at performing levels. Therefore, the only way they would be able to extract value from such assets is if they have some comparative advantage over the originators in terms of management skills. In the absence of any comparative advantage over the lenders, AMC will only serve the limited purpose of cleaning up banks’ balance sheets and will eventually become ineffective. In this sense, it is imperative that these specialised institutions are differentially empowered though legal and regulatory frameworks. B.8. The Committee has attempted to reflect these design principles in its recommendations. It is expected that a principle-based redesigning of the ARC model would go a long way in improving the performance and relevance of the sector. Chapter C. Extant Legal and Regulatory Framework for ARCs Legal Framework C.1. ARCs are registered and regulated under the Act. They acquire financial assets from banks/ FIs either on their own books or in the books of a trust set up for the purpose of securitisation and/ or reconstruction. Section 10 of the Act outlines the other permissible activities of the ARCs. Accordingly, ARCs are permitted to undertake only the business of asset reconstruction, securitisation and other fee-based business as enumerated under Section 10(1) of the Act. Any other activity can be undertaken by these entities only with the prior approval of RBI. Some of the important provisions of the Act specifically pertaining to ARCs are enumerated below: | Table-C1- Important provisions of the Act specific to ARCs | | Section 3 | Registration of ARCs | | Section 4 | Cancellation of Certificate of Registration | | Section 5 | Acquisition of Rights or Interest in Financial Assets | | Section 7 | Issue of Security by Raising of Receipts or Funds by ARCs | | Section 8 | Exemption from Registration of Security Receipt | | Section 9 | Measures for Asset Reconstruction | | Section 10 | Other Functions of ARC | | Section 12 | Power of RBI to determine Policy and issue Directions | | Section 12A | Power of RBI to call for Statements and Information | | Section 12B | Power of RBI to carry out Audit and Inspection | | Section 30A | Power of Adjudicating Authority to impose Penalty | | Section 30B | Appeal against Penalties | | Section 30C | Appellate Authority | C.2. Section 2(1)(c) and Section 2(1)(m) of the Act define the terms ‘bank’ and ‘financial institution(FI)’, respectively. For the purpose of the Act, bank means a banking company as defined under Section 5(c) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 (B R Act), or a corresponding new bank as defined under Section 5(da) of B R Act, or the State Bank of India, or a multi-state co-operative bank. The Central Government has been empowered by the Act to notify any other class of banks for the purpose of this Act. FI under the Act includes public financial institution as defined in Companies Act, 2013, International Finance Corporation established under the International Finance Corporation (Status, Immunities and Privileges) Act, 1958, specified institutions under Section 2(h)(ii) of RDDBFI Act, a debenture trustee registered with SEBI and appointed for secured debt securities and an ARC. Central Government has been empowered by the Act to notify other institutions including NBFCs as FI. Central Government has notified NBFCs (including HFCs) having asset size of Rs.100 crore and above as FIs. C.3. In terms of Section 5(1) of the Act, ARCs can acquire financial assets from banks and FIs as defined under the Act. Another significance of an entity (e.g. a NBFC) being classified as FI under the Act is that it also gets enforcement powers with respect to secured financial assets under Section 13 besides the eligibility to sell financial assets to ARCs. C.4. Section 7 of the Act empowers ARCs to issue security receipts (SRs) and only qualified buyers (QBs) are permitted to acquire such SRs. Section 2(1)(u) of the Act defines QBs to include a financial institution, insurance company, bank, state financial corporation, state industrial development corporation, ARC or any asset management company making investment on behalf of mutual fund or a SEBI registered foreign institutional investor, any category of non-institutional investors as may be specified by RBI or any other body corporate as may be specified by SEBI. C.5. ARCs for the purpose of securitisation create trusts which are governed by the provisions of the Indian Trust Act, 1882. Section 7(2A) of the SARFAESI Act specifies that such trusts are to be managed by ARCs, and ARCs shall hold the assets in trust for the benefit of the QBs. ARC regulations require that ARCs, as trustees, compulsorily invest and remain invested in at least 15% of the SRs of each class till the redemption of all the SRs issued by them under each scheme. ARCs skin in the game helps in aligning the interest of QBs (beneficiary) and the ARCs(trustee). Selling lenders may also acquire SRs as part of the consideration for transfer of assets to the trust. In fact, this has been the dominant practice till 2016. Typical transactions involved in securitisation done by ARCs are indicated in the Figure C1 below.  C.6. On acquisition of financial assets, ARCs are required to realise the financial assets within the maximum permitted period of eight years from the date of acquisition. Section 9(1) of the Act prescribes measures of asset reconstruction that can be used by ARCs. The term ‘Asset Reconstruction’ is defined under Section 2(1)(b) of the Act as acquisition by any ARC of any right or interest of any bank or financial institution in any financial assistance for the purpose of realisation of such financial assistance. The Act empowers RBI under Section 9(2) to issue guidelines on the measures of asset reconstruction and Section 9(3) makes it binding on ARCs to take these measure in accordance with RBI guidelines. Regulatory Framework C.7. RBI, in exercise of the powers conferred by Sections 3, 9, 10 and 12 of the Act has issued the “Securitisation Companies and Reconstruction Companies (Reserve Bank) Guidelines and Directions, 2003”. These guidelines cover the whole gamut of ARCs’ functioning such as registration, measures of asset reconstruction, functions of the company, prudential norms, acquisition of financial assets and related matters. A list of important guidelines issued by RBI regarding the working of the ARCs is given in Annex II. These guidelines were last consolidated as of July 2015 and need to be updated. Recommendation: The various guidelines applicable to ARCs may be consolidated into a single set of Master Directions, which may be updated as and when regulatory changes are made. C.8. Section 2(1)(zh) of the Act defines Sponsor as any person holding not less than 10% of the paid-up equity capital of an ARC. Section 3(3)(f) of the Act empowers RBI to specify fit and proper criteria for Sponsors of the ARCs. Accordingly, the RBI Master Direction dated October 25, 2018 enumerates the criteria for determination of fit and proper status of the sponsors and provides a framework for monitoring of such status. Among other things, assessment of sources and stability of funds is integral to this exercise. These requirements seek to ensure that sponsor’s/management’s/executives’ integrity, reputation, track record and compliance with applicable laws and regulations meet the regulatory expectations. Further, the Act as well as regulation require prior approval of RBI for all appointment/re-appointment of directors/ managing director/ CEO or for change in Sponsors. Other important regulation pertaining to various prudential norms applicable to ARCs are given below in brief: | Table-C2- Important regulations relating to ARCs | | Net Owned Fund | Minimum Rs.100 crore on an ongoing basis | | Acquisition of financial Assets | Not allowed on a bilateral basis from sponsor banks/ FIs or an entity in the Group. However, these entities are allowed to participate in public auctions | | Investment in SRs | Minimum 15% of SRs in each class, under each scheme | | Realisation of Assets | 5 years, may be extended up to 3 more years with the approval of their Board | | CRAR (%) | 15% | | Asset Classification (Assets that are held in books of ARC) | Standard: During the planning period of 6 months otherwise if not an NPA;

Sub-standard Asset: for a period not exceeding twelve months from the date it was classified as NPA;

Doubtful Asset: if the asset remains a sub-standard asset for a period exceeding twelve months;

Loss Asset: if the asset is non-performing for a period exceeding 36 months; the financial asset including SRs is not realized within the total time frame specified | | Provisioning requirements | Sub-standard Asset: 10% of the outstanding Doubtful Asset:

(i) 100% provision to the extent the asset is not covered by the estimated realisable value of security;

(ii) In addition to (i) above, 50% of the remaining outstanding Loss Asset: (i) Entire asset shall be written off;

(ii) If the asset is retained in the books, 100% shall be provided for | | Income Recognition | a. Yield on SRs as well as Upside Income should be recognised only after full redemption of SRs

b. Management Fee should be calculated as a % of net asset value (NAV) at the lower end of the range specified by Credit Rating Agency. | C.9. As mentioned above, the Act empowers the RBI under Section 9(2) to issue guidelines on measures for reconstruction of assets. Accordingly, detailed guidelines have been issued in this respect by RBI. A brief snapshot of these guidelines is as follows: | Table-C3 - Important Regulations regarding Measures for Asset Reconstruction | | Measures | Regulatory provisions | | Change in/ Takeover of Management of the Business of the Borrower | • In accordance with provisions of Section 15 of the Act and as per Board approved policy;

• If amount due to the ARC trust is at least 25% of the total assets owned by the borrower. If borrower is financed by more than one secured creditor (including ARC) holding not less than 60% of outstanding SRs agree to such action.

• Grounds - Wilful default, incompetent management or the management acting against the interest of creditors, fraudulent transactions, etc. | | Sale/ Lease of Business of the Borrower | RBI has not issued necessary guidelines in this regard | | Rescheduling of Debts payable by the Borrower | As per Board approved policy of the ARC | | Enforcement of Security Interest | • In accordance with provisions of Section 13 of the Act.

• The ARC may acquire the secured assets, either for its own use or for resale, only if the sale is conducted through a public auction. | | Settlement of Dues payable by the Borrower | • As per Board approved policy | | Conversion of Debt into Equity in a Borrower Company | • Shareholding by the ARC/ trust shall not exceed 26% or sectoral FDI limit of the post converted equity of the company under reconstruction. The 26% limit can be exceeded provided the ARC meets certain criteria.

• As per Board approved policy | C.10. ARCs are permitted to deploy their funds for undertaking restructuring of acquired assets with the sole purpose of realising their dues. Trusts may also utilize a part of funds raised under a scheme from the QBs for restructuring of assets acquired under relative schemes subject to certain conditions. One of the conditions requires that the extent of funds that shall be utilized for reconstruction purpose should not be more than 25% of the funds raised under the scheme. C.11. ARCs’ efforts towards resolution of assets results in redemption of SRs. However, from the recovery made by ARCs, they claim the management fee for managing the assets, expenses and incentives, if any, from the respective trusts. Residual recovery is used to redeem the SRs issued to the QBs. Residual recovery in excess of the acquisition cost, generally referred to as ‘upside income’, is distributed among the QBs and ARCs as per the agreed terms. Figure C2 below depicts the typical distribution of recovery from the resolution of a securitised asset.  C.12. Management fee of ARCs is based on the NAV of the SRs. NAV in turn depends on the rating obtained from a SEBI registered Credit Rating Agency (CRA). ARCs are required to obtain the initial rating within a period of six months of acquisition of assets. Thereafter, the rating is reviewed by a CRA on half yearly basis. Rating is given in terms of 'recovery rating scale' which has an associated range of probable recovery expressed in percentage terms. NAV is arrived at by multiplying the face value of outstanding SRs with the lower end of the said range. Management fee is to be recognised on accrual basis and is to be reversed, if not realised within 180 days or if NAV falls below 50% of face value within the said period. Extant guidelines for ARCs provide that the rationale for the rating should be disclosed by CRAs to ARCs on an ongoing basis. C.13. Prudential accounting norms require that SRs held by the ARC which have not been redeemed within the maximum permitted timeframe of 8 years are to be treated as loss assets. Under Section 7(3) of the Act, in the event of non-realisation of assets within the specified timeframe, QBs holding SRs of not less than seventy-five percent of the total value of SRs issued under a scheme are empowered to call a meeting of all the QBs and pass a resolution binding on the ARC. Chapter D. Business and Financial Model of ARCs D.1. Acquisition and Securitisation of Financial Assets D.1.1. The business of ARCs involves acquisition of stressed assets from lenders and recovery using various measures of asset reconstruction. It typically also involves securitisation of acquired assets. Acquisition of assets by ARCs, in terms of book value, grew at a CAGR of 27.2% for the period FY04 to FY21. As depicted in Chart D1 below, a considerable jump in acquisition was seen in FY14, followed by an overall upward trend over the succeeding years. Data shows that overall 79.8% of assets flowing into the ARC sector has been from the banks. Assets acquired from PSBs alone constituted 51.6% of the total assets acquired by the ARC sector. However, FY17 onwards, ARCs have been acquiring financial assets from a diverse set of entities.  D.1.2. NBFCs have emerged as a significant class of sellers of stressed assets since the notification of select NBFCs as FIs for the purpose of Act in FY17. During the period FY17-FY21 acquisition from NBFCs grew at a CAGR of 87.9%. In fact, in FY21, NBFCs were the largest supplier of stressed assets among the eligible entities. The emergence of NBFCs as a significant class of sellers can be attributed to multiple factors. One of the factors may be that, after initial notification in FY17, Central Government has been notifying an increasing number of NBFCs as FIs. At present, all NBFCs having asset size of Rs.100 crore and above are notified as FIs. Another underlying factor may be the liquidity crunch faced by the NBFC sector around FY19 which would have pushed them to increase encashment of financial assets. D.1.3. The increase in NBFCs’ share in supply of financial assets can also be explained in part by the shrinking of banks’ sale of financial assets to ARCs. PSBs’ sales to ARCs have been declining from FY19 onwards. One of the factors behind this decline may be the introduction of progressive provisioning for banks’ SR based deals which was introduced vide RBI circular dated September 1, 2016 and came into full force from FY19 onwards. To understand the banks’ use of ARCs as a mechanism for management of stressed assets, a comparison has been made between the GNPA (including assets sold to ARC)4 of scheduled commercial banks and ARC’s acquisition of financial assets from banks for the period of FY08 to FY19 in Chart D2 below. The data indicates that post FY14 there has been a downward trend in the percentage of NPAs sold to ARCs despite the upward trend in the level of GNPA in SCBs. Apart from the progressive provisioning discussed above, the emergence of IBC as an alternative resolution mechanism may also have contributed to this trend.  D.1.4. During the period FY04-FY21, the average discount rate at which ARCs acquired the financial assets stood at 66%. However, there has been an approximately 15 percentage point decline in the average discount rate during FY14-FY21 as compared to the period before it. Chart D3 below highlights this decline. The decline in the discount rate may reflect increased quality consciousness of ARCs, as the ‘skin in the game’ requirement for them (to hold in the ARC’s own books a minimum percentage of the SRs issued) was increased to 15% from 5% vide circular dated August 05, 2014. D.1.5. SRs issued by ARCs as part of securitisation of assets acquired grew at a CAGR of 30% during the period FY04-FY21. A snapshot of the current status of SRs originated in a particular year is shown in the Chart D4 below. ARCs are required to resolve the assets within a maximum of 8 years of acquisition of financial assets and redeem the SRs representing the assets. Therefore, the period after FY13 has SRs for which resolution is still underway. The overall redemption of SRs issued by the ARC sector during FY04 to FY13 was 68.6% of the total value of SRs issued. The redemption of SRs issued during this period, as a percentage of the book value of stressed assets acquired, however comes down to as low as 14.29%. This implies that banks and other investors could recover only about 14% of the amount owed by their borrowers5. A snapshot of the status of SRs originated during FY04-13 and FY14-21 is indicated in Table D1 below. | Table D1- Status of SRs | | | FY04-FY13 | FY14-FY21 | | | as % of Total SRs issued | as % of Book value acquired | as % of Total SRs issued | as % of Book value acquired | | Redeemed | 68.6% | 14.3% | 28.5% | 10.4% | | Written off | 31.4% | 6.5% | 0.7% | 0.3% | | Outstanding | 0.0% | 0.0% | 70.8% | 25.9% | D.1.6. The above data shows that the discount rate on book value has been high and a significant portion of SRs have had to be written off. This indicates two issues with the current market: (a) low rates of redemption, and (b) inflated acquisition costs. While enhancing the ability of ARCs to undertake asset reconstruction, we also recognize the importance of creating incentives to ensure that the price discovery process yields the true value of SRs. Such a process would minimize the write-off of SRs while aligning the discount (to asset book value) at which SRs are issued, to better reflect the realisable value of the assets sold. The relevant incentives are integrally linked with the percentage of investment in SRs by non-lender entities. Low proportions of such investment by non-lender entities are likely to be associated with high deal values. On the other hand, at high proportions of such investment by non-lender entities, the buyer’s bids are likely to be lower than the lender’s ask prices, thereby restricting market activity. Hence an economic model was developed to examine the combinations of acquisition cost and investment by non-lender entities (conversely, holding of SRs by lenders) that would be acceptable to both lenders and ARCs, and would yield true values of SRs. The model identifies the ranges of investment by non-lender entities that would facilitate the discovery of true value through the market mechanism. If the market operates in this range, (which is specified in paragraph D.1.7(b) below), we become confident that the market mechanism is leading to the discovery of true value. Hence, prudential norms with regard to provisioning can be relaxed. The model also indicates that the relaxation of the abovementioned norms is not merely justified on conceptual grounds, but necessary to kickstart the market. Details of the model are presented in the Annex III. D.1.7. One of the significant deterrents to sale of stressed assets by lenders to ARCs is that they are required to book the losses on immediate basis. This especially acts as a deterrent for the sale of recent (low vintage) NPAs with lower levels of provisioning on the lenders’ books. On the other hand, when lower vintage NPAs are assigned to ARCs, the chances of revival/ maximization of recovery are higher. ARCs may be able to resolve such NPAs through revival of business before resorting to other legal options for recovery. In order to incentivize lenders to sell stressed assets, especially with focus on those assets with low vintage, certain options may be considered, as elaborated below: (a) Currently, on sale of asset below Net Book Value, lenders are required to provide for the shortfall at the time of sale. However, as per guidelines dated February 26, 20146, as an incentive for early sale of NPAs RBI had given a dispensation to banks for amortising the shortfall on sale of NPAs to ARCs, over a period of two years. The dispensation was valid up to March 31, 2015 but was later extended till March 31, 2016 vide circular dated May 21, 2015. Subsequently vide circular dated June 13, 2016, for assets sold between April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2017, banks were allowed to amortise the shortfall over a period of four quarters. As an incentive for early sale of NPAs, the above dispensation may be extended further, and banks may be allowed, on an on-going basis, to spread loss on sale of financial assets to ARCs, over a period of two years, in line with the previous guidelines, subject to suitable disclosures in the published accounts. Illustrative example – | Gross Exposure (A) | Rs.100 | | Provisioning (B) | Rs.15 | | Net Exposure (C=A-B) | Rs.85 | | Sale Consideration (D) | Rs.50 | | Loss at the time of Sale (E=C-D) | Rs.35 | | Provisioning required in terms of current guidelines | Rs.35 on sale | | Recommended guidelines | Provisioning:

Year 1 @50% of Loss : Rs.17.50