This chapter is divided into two parts. Part I sets the tone under the broad theme of ‘optimal financial system configuration’, while Part II discusses the regulatory and developmental issues related to the financial sector.1 The theme aims to bring into focus some of the dilemmas relating to the size and composition of the financial system and its effectiveness in supporting the real economy. The discussion takes a look at the process of financial intermediation, efficacy of resource allocation along with financial risk-sharing under different configurations of the financial system. Part I concludes with a brief review of the domestic financial market landscape. Part I

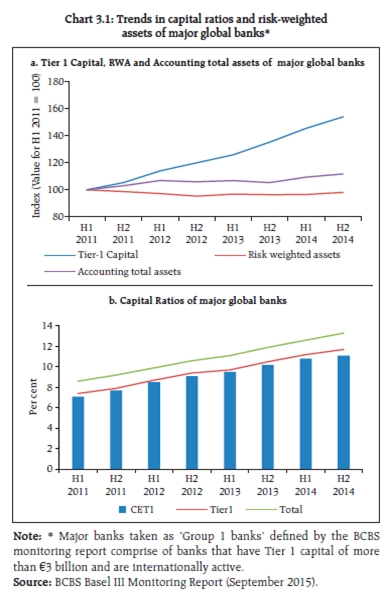

An optimal configuration for the financial system – Banks versus Market 3.i The financial sector primarily exists to serve the needs of the real economy by channelising savings towards productive purposes. As activity in the real economy expands and diversifies, the financial sector is also expected to grow, both in scale and scope, to facilitate the process of economic growth and development. While there is a significant relationship between economic growth and financial sector development2, the causation may run both ways. Production and distribution of economic information, allocation of resources, monitoring and control over the use of resources, facilitating the diversification and management of risks among others have been identified as some of the key functions of the financial sector which aid economic growth.3 The efficiency and resilience with which a financial system carries out these vital functions define the stability of the system, which in turn is important for sustainable economic growth. 3.ii While more developed financial systems are generally expected to be more stable, it has been observed that beyond a certain size and level of complexity, the benefits of financial development may prove counterproductive for stability. This was one of the major learnings from the experience of the global financial crisis (GFC), necessitating significant regulatory reforms and a balance between innovation and regulation.4 3.iii The theme of Financial Stability Report (FSR June 2015)5 focussed on the importance of a balanced regulatory approach and supervisory strategies so that the regulation itself does not stifle innovation while ensuring that the goals and incentives of financial institutions and financial markets remain aligned with the broader goals of optimising the efficiency for all stakeholders and supporting sustainable economic growth. 3.iv The ‘re-regulation’ that followed the GFC world over has probably ensured a more resilient banking sector through enhanced capital buffers. In the meanwhile, resource flows through financial markets have been picking up at a greater pace compared to bank intermediation, reflecting enhanced ‘financial risk sharing’. Though there has been no conclusive evidence as to the superiority of either a bank-dominated financial system or a market-dominated one, the GFC exposed the chinks in both. Excesses committed through both these channels of financial intermediation have swayed some economies violently between bubbles and rubbles with the spillovers being significant around them. 3.v The developments also brought new dimensions in the process of financial intermediation – ‘vertical intermediation’ that involves money moving from savers to users of funds and ‘horizontal intermediation’ wherein market participants move funds amongst themselves. The excesses mentioned earlier were supposed to be the result of an overgrowth of ‘horizontal intermediation’6. Besides, a significant part of the lending goes into financing existing assets and many financial systems have not put in place mechanisms to capture how much of the new lending goes into the acquisition of new assets. 3.vi The special theme of this report takes a look at the process of financial intermediation, efficacy of resource allocation and financial risk sharing through different configurations of financial systems as also their role in corporate governance structures. Bank-dominated and market-dominated financial systems 3.vii Traditionally, on the one extreme financial intermediation has been characterised by a bank-dominated system (Europe and Japan) with a relatively minor role played by capital markets and by a market-dominated system (the US) with banks and financial institutions playing a lesser role in supporting the dominant market-based system, with some other systems falling in between (that of the UK). In a way these different frameworks were the result either of the failure of extant frameworks or of policy responses to various provocations during phases of the evolution of financial markets. For instance, in the US, the Great Crash of 1929, the Glass Steagall Act and the restrictions on interstate banks restrained the banks and gave a fillip to the markets. The development of capital markets in the UK owes its origins to the wars that England fought as the London capital market became an important source of funds for the government. Though Germany and Japan have a bank dominated system, as against the Anglo-Saxon market-based system, there are some significant differences in the sense that the hausbank system in Germany developed in the private sector whereas the development of the mainbank system in Japan was actively supported by the government. Institutions versus markets: Competition or complementarity? 3.viii There are two broad views with regard to ‘financial institutions versus markets’. One view is that financial institutions and markets are competing sources of financing (Dewatripont and Maskin 1995; Allen and Gale 1997; Boot and Thakor 1997). As per this ‘competing’ view, financial institutions, by avoiding the use of ‘markets’ may be able to offer inter-temporal risk-smoothing services that markets cannot. Further, according to this view, markets are incomplete (in a market based system) and hence they expose households and investors to greater risks due to frequent fluctuations of asset values caused by investors’ beliefs and market information. However, competition from the markets may undermine the risk sharing benefits that institutions offer, since there will be situations in which the returns offered on the market diverge from those offered by institutions engaged in offering risk-sharing contracts (Allen and Gale, 1997). 3.ix Another view suggests that banks and capital markets are integral parts of a co-evolving financial system, wherein they not only compete, but also complement and co-evolve (Bossone, 2010; Song and Thakor, 2010). 3.x This view instead of looking at the ‘markets’ as an end in themselves, supports the co-existence and co-evolution of banks and markets and is based on the premise that ‘the financial system is plagued by two frictions impeding a borrower’s ability to obtain financing’ - the ‘certification friction’ that arises due to the imperfect information about the credit quality of the borrower and the ‘financing friction’ that arises from the external financing costs faced by a borrower. This view further posits that because of the certification friction there is a possibility that a creditworthy borrower may be wrongly denied credit and that the financing friction imposes excessive costs to the detriment of foregone good investment opportunities. Thus according to the ‘complementarity’ view - ’banks are better at diminishing the certification friction because of their credit analysis expertise, whereas capital markets are better at resolving the financing friction by providing a more liquid market for the borrower’s security and thereby lowering borrowing costs’ (Song and Thakor, 2010)7. In other words, even if there is an effort to spread the overall risks away from the banks in a hitherto bank-dominated financial system, one cannot undermine the role of banks, which do credit screening in a competitive market and that information becomes a vital input in the process of price discovery and risk management in capital markets. However, banks’ efforts in disseminating the information gathered through credit screening could be severely curtailed if active secondary markets are absent. 3.xi Song and Thakor (2010) further argue that such a co-dependence connects the banks and markets through two channels - securitisation and regulatory requirements of risk-sensitive bank capital. Under the process of securitisation, through credit screening the banking system certifies borrower’s credit quality (hence the importance of ensuring the quality of loan origination for developing a credible and sustainable securitisation market) and the markets provide the financing. Development of capital markets eases financing friction and thus reduces the cost of capital for banks. This helps banks in raising additional capital to extend riskier loans which they might avoid otherwise. Thus the complementarity model suggests a feedback loop between the banks and markets and lets them focus on what they can do best - credit analysis by banks and provision of finance by markets. In the absence of such an understanding, there is a possibility of misaligned regulatory policies and a scope for borrowers ‘gaming’ the system, which leads the discussion into corporate governance issues. 3.xii While acknowledging the role of the financial sector in corporate governance, Allen and Gale (1997) observe that ‘a careful comparison of financial system is not very supportive of existing governance theories. Markets for corporate control simply do not exist in some countries, and the evidence for the monitoring role of banks is weak.’ The importance of banks emanates from their role of delegated monitors to ensure proper use of resources lent to firms besides sharing of risks in the economy by diversifying and smoothing fluctuations over time and also ensuring corporate governance and helping overcome asymmetric information problems by forming long-lived relationships with firms (Allen and Carletti, 2008). In other words, the role of banks in disciplining borrowers is subtly different from the kind of ‘market discipline’ that capital markets are supposed to ensure. 3.xiii Some studies also suggest that expanding bank activities into capital markets by allowing them to hold equity stakes in firms might generate efficiency gains (Bosonne and Lee, 2004; Li and Masulius, 2004). Access to larger capital markets reduces bank costs by providing banks with more efficient instruments of risk management and reputation signalling which enable them to economise on the financial capital. However, ‘the informational externalities springing from capital markets strengthen the competitiveness of only those banks that are best equipped to benefit from efficient use of information, while they inevitably penalise less equipped banks’ (Bosonne, 2010). Will banks continue to remain special in the financial system? 3.xiv There are a few things that give special status to banking institutions within the universe of financial institutions. Given their unique role in payment systems and in the distribution of liquidity, banks are prone to systemic risks in a way that distinguishes them from other financial institutions. As deposit accepting financial institutions, limited liability joint stock banking companies have been in a peculiar situation as they promise to pay ‘all’ demand deposits on demand while engaging in a business of liquidity (converting liquid deposits into less liquid loans) and maturity transformation (converting short-term deposits to long-term loans). 3.xv Innovations for addressing these issues and a supportive regulatory stance in fact encouraged securitisation and greater risk sharing. However, in the light of circumstances that led to financial crises what probably could have been overlooked is whether the risks that were passed on by the banks were taken by those who did not have the capacity to absorb them. The danger in such situations comes from nontransparent markets and insufficient attention on the part of those who should otherwise be mindful of the ultimate distribution of credit risks. At the same time, in the absence of transparent and liquid capital markets, presumption of having one and imputing asset prices through artificial means could bring distortions in resource allocation. If the realised value was less than the true/fair value it might bring some endogeneity in the response of market participants. 3.xvi Deposit insurance is another area that makes banks distinct. In a way one can argue that partial deposit insurance encouraged banks to undertake risky lending options and capital requirements acted as a counterforce to such temptations. However, innovations like securitisation and credit default swaps fundamentally changed the way in which he banking business was done and also the relationship between lenders and borrowers, by providing an avenue for ‘more efficient use of capital’. On the other hand, the impact of the so-called moral hazard embedded in deposit insurance may be magnified in an alternate view according to which – ‘banks do not as too many text books still suggest, take deposits of existing money from savers and lend it to borrowers: they create credit and money ex nihilo – extending a loan to the borrower and simultaneously crediting the borrower’s money account’ (Turner, 2013). 3.xvii Another important dimension with regard to the evolution and configuration of the financial sector is the role of political intervention which may take different degrees and forms at various stages of financial system development (Song and Thakor 2012). In the initial stages of development of a financial sector, this may generally manifest through capital contribution or subsidies to banks by the government, with or without ‘directed lending’ prescriptions, to ensure broader coverage of bank lending. At intermediate and advanced stages of financial sector development, information acquisition and processing become less costly and bank profits increase thus reducing dependence on the government for capital. However, in the advanced stages political intervention may be seen in the form of ‘directed lending’ (which may theoretically mean extending the coverage of bank lending to ‘riskier’ borrowers who otherwise would tend to be financially excluded). Challenges facing traditional banking institutions and markets 3.xviii Globally, the post-crisis debates and fundamental questions regarding the future of banking are still continuing. The on-going ‘vollgeld initiative’ in Switzerland, which aims to restrict bank lending to banks’ capital bases and not through depositors’ money is an extreme example of such challenges. While the banking industry has been preoccupied with addressing problems which surfaced during the GFC and are grappling with the implementation of still evolving post-crisis regulations, emergence of alternative forms of financial services supported by technological advances are also challenging the traditional banking business. 3.xix Reduced institutional participation in the markets, though necessitated in the context of regulatory reforms post GFC along with massive asset purchase programmes by various central banks, have interfered with market liquidity and the pricing mechanism. On the other hand, with banks undertaking balance sheet repairs and facing capital constraints, other forms of financial intermediation need to fill this gap in meeting the economies’ credit needs. But the ensuing shifts will require redrawing regulatory perimeters and responses in such a way that the new frameworks balance innovation and financial stability. 3.xx Although the forces of innovation will continue to affect the functioning of institutions and markets, and in turn the configuration of financial systems, the approach to regulation may also influence this process of transition from a bank-dominated to a market-led system in particular and the evolution of a financial system in general. While it is necessary to align the policy environment and innovation strategies with available regulatory capacity, the latter needs to be upgraded to match the natural course of economic development. Sometimes necessary innovations will not even take off because policymaking is mired in paradoxes of innovative endeavours such as the ‘success failure paradox’ and the ‘feedback rigidity paradox’8. Finally, as a significant portion of the innovations is being led by technology, the challenge for all the stakeholders in the financial system is to guard against the downsides of technology. (Box 3.i) Box 3.i: Technology: the agathokakological companion? Previous financial stability reports have sporadically talked about the impact of technology and digitisation on the financial sector with the last one specifically cautioning about the challenges posed by cyber threats calling for board level appreciation of the issues involved in individual organisations.9 While technology and digitisation have become integral parts of an evolving financial system, potential risks associated with them are less appreciated ex ante, and for regulated financial entities or for that matter even for regulators, it becomes difficult to assess the impact and provide capital buffers for potential operational risks. While the recent central bank heist highlights the dangers of how even the nervous system of an established global payments mechanism can be easily targeted, a paper published by IO Active on remote hacking of a car is an indication of how every ecosystem (a complex network or an interconnected system) is increasingly getting vulnerable in the absence of appropriate cyber defence mechanisms. ‘Denial of service’ in information technology parlance, is something that sounds scary. While the current cyber defence mechanisms appear to be robust as they have been withstanding innumerable cyber-attacks, a multi-sigma event of a failure of such a mechanism in an increasingly networked global financial system is something all the stakeholders need to guard against. Regulation in general should not be standing in the way of innovation as regulation is but an effort to enhance the upside of an innovation. Thus all regulations are aimed at maximising the ‘public good’ outcome of any innovation - while curtailing its downside. Interesting though, financial market regulators have to deal with new forms of ‘insider trading’ – strictly going by the definition of the term – as digitisation of data is providing a recipe for digital criminals who steal data and make money with the help of what is otherwise ‘non-public corporate information’. The solutions for addressing cyber threats get compounded given their cross border reach pervading different legal jurisdictions. On the other hand, a lack of effort to voluntarily share information on cyberattacks makes it difficult to tackle their recurrence. This has assumed greater significance with the secular growth of financial technology (FinTech) over the last couple of years. Led by start-ups, FinTechs, are basically technology enabled financial solutions which bring about digital innovative disruptions not only in the development of applications and products, but also in business models of the banking and financial services sector. There is no gainsaying that FinTechs have brought in amazing customer experience ranging from ‘smart contracts’ to simple ‘shake for balance’ function on a bank’s app10 besides providing faster and easier delivery channels. However, increased levels of hacking threats and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks have the potential for causing significant disruptions in the services of these ventures apart from risks related to sensitive customer information and cyber frauds. Thus, the onerous task of efficient monitoring and management of the attendant information technology (IT) systems and data security risks are key to enhancing the net benefits of disruptive innovations. Search for a better balance between banks and market for the Indian financial system 3.xxi While India continues to be a bank dominated financial system, recent trends show that the flow of resources through non-bank sources is comparable to that from banks. With banks undertaking the much needed balance sheet repairs and a section of the corporate sector coming to terms with deleveraging, the onus of providing credit falls on the other actors. Amidst sluggish bank credit growth, capital markets do seem to be supporting the needs of the commercial sector (Chart 3.i). However, the increasing use of short term debt instruments and the private placement route (as against long term public issuance of debt securities) indicate that the debt markets have to go a long way before they can effectively supplement bank credit and share risks. 3.xxii A closer examination of the domestic financial markets does indicate that bank credit is closed to a section of borrowers exhibiting a strong network effect in their resource/capital allocation decisions. As a result, lending to un-networked small borrowers seems much less preferred - other than those that form part of ‘directed lending’ obligations, which bring their own distortions. Thus one gets to see an avoidable concentration risk. On the other hand, despite the strides made since the start of reforms a quarter century ago, capital markets lack breadth and depth when it comes to bond financing. The extant constraints faced by both the institutional and market channels in financial intermediation, however, may seem rational. There is, thus, a need to bring in a supporting ecosystem if both the channels need to complement and co-evolve. 3.xxiii While concerns emanating from the significant concentration of large exposures in banks’ books are justified in the current milieu, the challenge is to shift a part of the resource allocations to bond financing without impacting aggregate allocative efficiency and economic welfare. The most important challenges are those arising out of accounting treatment of loans and bonds, distortions due to illiquid secondary markets in bonds and the absence of a term benchmark. 3.xxiv First, the accounting treatment of bonds is not symmetric with loans, given the difference in the ease of their transferability. In addition, most of the loans are based on floating rate bank specific benchmarks while bonds in general are fixed coupon products. Hence bonds and loans are also not symmetric from the market risk perspective and that makes the asymmetry in accounting treatment an important issue. 3.xxv Second, passive holdings of corporate bonds in banks’ books do not add any information for non-bank holders of bonds regarding the current credit status of the issuer. Yet, illiquid bond markets imply that impact costs of bonds are higher and a valuation norm that does not take into account these high impact costs, reduces banks’ incentives to trade in them. In the absence of liquidity, any valuation is ‘theoretical’. Moreover, banks being a major contributor to the valuation polling process, the incentive to show ‘off market’ prices, given that such bonds are long only positions cannot be ruled out. 3.xxvi Further, given that the sizes of corporate bond issues are relatively small, the incentive to distribute the entire issue among a few subscribers preferably the ‘buy-and-hold’ type of investors (including banks) who would in turn prefer to hold them till maturity, while using passive polled valuations to value them run the risk, that in a hypothetical event of actual disposal, of the realised valuations being quite at variance with the polled ones. Thus, illiquid secondary markets create their own negative externalities in valuation of bonds which in turn can generate their own negative feedback impeding secondary market liquidity further. This is because, if secondary market valuations are not ‘market clearing’ ones due to the factors mentioned earlier, clearly, the end investors looking to invest in such securities are likely to get a better bargain in primary markets. Lack of interest from primary investors in secondary markets implies that the banks will carry a low inventory of such securities which in turn stand in the way of secondary market liquidity. 3.xxvii Third, the distortions created by differing accounting treatments and an illiquid secondary market implies that banks have few alternatives to be ‘valuation neutral’ with respect to their corporate bond portfolios, in the absence of standard tenor specific benchmarks (term curve) against which their loan books can be priced – a prerequisite for a transition from bank specific benchmarks. Establishing such benchmarks and enabling interest rate swaps in them are likely to enable the banks to convert fixed coupon corporate bond books to floating or floating rate corporate loan books to fixed rate assets based on their requirements thus making the ‘accounting’ issue much less relevant. More importantly, such swaps will like to standardise the pricing of corporate bonds vis-à-vis their corporate loan counterparts through the development of an underlying asset swap market and hence would tighten the corporate loan-corporate bond basis for the same obligor. Such asset swaps form a part of the essential building blocks for the pricing of credit derivatives. 3.xxviii In other words, what all this means is the complementarity of a commensurate market for interest rate derivatives for bringing institutional and market based intermediation closer. This will also help the securitisation market which is currently rife with asymmetric information that impairs liquidity. 3.xxix Finally, efforts towards greater transparency in the private placement market, encouragement for secondary market trading and nudging large borrowers to increasingly access the corporate bond market will help in achieving a better balance between market-based and bank-based finance. Part – II

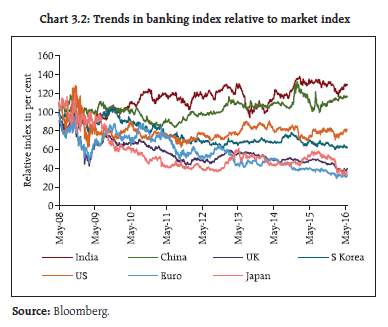

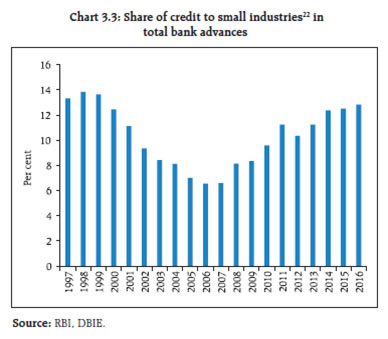

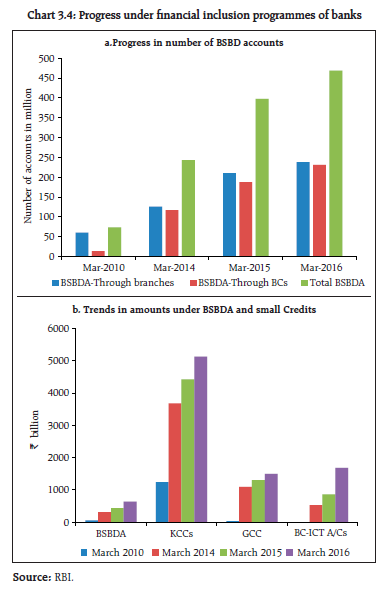

Financial sector in India – Regulation and development While global regulatory reforms have resulted in banks’ improved capital ratios, there will be challenges in terms of ensuring continued flow of credit and sustainable profitability for financial institutions. In India as the banking sector is grappling with balance sheet repairs, other institutions such as non-banking finance companies will need to play a bigger role even as the capital market will need to facilitate easy access to credit and equity financing for economically useful and viable projects. With the expanding mutual funds sector, India’s securities market continues to grow, covering a greater section of the investor population. It is important to ensure that eligible foreign investments are not attracted to offshore markets for the lack of required flexibility in terms of instruments and appropriate micro-structure of domestic markets. The depth of the commodity derivatives market should increase, alongside the necessary improvements in physical market infrastructure. The potential concentration of risks from reinsurance activities needs to be properly evaluated and managed, while keeping a check on possible mis-selling under bancassurance. The move towards risk based supervision and steps for formalising retirement planning advisory services will help in the development of the pension sector. The international regulatory reform agenda – progress and dilemmas 3.1 The previous issues of the Financial Stability Report (FSR), while noting the progress in formulating and implementing post-crisis international regulatory reforms, stressed the importance of appreciating differences in national priorities in deciding the pace and assessing the impact of some of the agreed reforms. That said, one of the most tangible effects of the reforms has been observed in banks’ larger and better quality capital buffers (Chart 3.1) and gradual reduction in leverage11. 3.2 Amidst various regulatory prescriptions to contain banks from taking excessive risks, the proposed new regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures under Basel III and the possibility of applying large limits on such exposures, might push up capital requirements for banks further, especially in emerging market economies (EMEs). Such regulations may also have repercussions for government securities markets. While strengthening regulation is expected to have a net positive impact in the long term, the challenge is to manage the current transition phase marked by falling revenues and narrowing margins of banks and the need for reworking business models and strategies in the face of developments arising from other factors such as rapid technological changes. In this context, there is a need for banks to recognise the importance of good governance systems and internalisation of the link between trust and business growth to find the right balance in view of the limitations and cost implications of more detailed regulations and closer supervision.  3.3 The global financial sector has to overcome the impact of the dent in public trust, credibility and integrity of institutions and market mechanisms caused by many instances of misconduct and unethical approaches resulting in heavy financial penalties in many cases. The corporate governance principles12 laid down by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) are also aimed at promoting public confidence, upholding the safety and soundness of the banking system and providing a framework for banks and supervisors with emphasis on issues related to transparency and accountability in ‘board’ level governance and compensation practices. Such a framework and other regulations touch upon the importance of a risk culture and client protection. In the meanwhile, under the new US regulatory proposals, banking and finance executives are sought to face tougher bonus deferrals and ‘clawbacks’. The UK, which as of now follows European Union (EU) rules, has already imposed ‘clawback’ rules on senior bankers’ pay and bonuses. On their part, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) are pitching for ‘unbundling’ whereby brokers’ research costs are to be borne by the manager and not the client. In its 2015 review, one of the main findings of the FCA was that the ‘hospitality’ exchanged in the asset management industry did not always seem to be designed to improve the quality of customer service. In this context, mis-selling of financial products in the Indian context may also belong to the same ilk. Domestic financial system Banking sector 3.4 Previous FSRs have focussed on asset quality, capital levels and profitability related challenges facing Indian banks, especially public sector banks (PSBs). While the deterioration in performance parameters of Indian banks was primarily caused by the economic downturn, other factors, such as weaknesses in governance, appraisal and risk management processes and imprudence of banks coupled with the corporate sector’s excessive leverage, and in some cases misdemeanours also played a role. 3.5 With PSBs having a dominant share in the banking sector, the Government has taken some concrete steps for addressing the entire spectrum of issues for improving the governance, capital-base and performance of PSBs13, including establishing the Banks Board Bureau and introducing key performance indicators (KPIs). 3.6 The June 2015 issue of FSR stressed the paramount importance of speedily addressing extant asset quality issues, based on the premise that balance sheet risks increase non-linearly with deterioration in asset quality14. Apart from the measures taken by the Government with respect to the distressed industrial sectors, the Reserve Bank has also undertaken steps such as formation of Joint Lenders’ Forum (JLF) for revitalising stressed assets in the system, flexible structuring for long term project loans to infrastructure and core industries, and Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR) scheme. Along with the creation of the Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC), such regulatory steps will enable banks to take prompt steps for early identification of asset quality problems, timely restructuring of viable assets and recovery or sale of unviable assets15. All these efforts consummated in a comprehensive Asset Quality Review (AQR) undertaken by the Reserve Bank. 3.7 While these developments have had an adverse impact on banks’ stock market valuations in the short term, Indian banks seem to be faring better than their global peers in terms of their performance vis-à-vis the broader stock market indices (Chart 3.2). Asset quality review (AQR) 3.8 AQR covered 36 banks (including all PSBs) which accounted for 93 per cent of the SCBs’ gross advances. The sample reviewed under AQR constituted more than 80 per cent of the total credit outstanding and 5 per cent of the number of accounts of the banking system reported through CRILC. The exercise sought to validate objective compliance of banks with applicable income recognition, asset classification and provisioning (IRACP) norms and exceptions were reported by the supervisors as divergences in asset classification / provisioning. The major objectives of the AQR exercise were: • To examine the assessment of asset quality at the bank level and at the system level as a whole. • To uniformly deal with cases of divergence in identifying NPAs/ additional provisioning across banks. • To ensure early finalisation and communication of divergences in provisioning giving banks sufficient time to plan the additional provisioning requirements so that they can present clean and fully provisioned balance sheets by March 2017. The findings of the review were conveyed to the banks to ensure effective compliance with regulatory prescriptions.  3.9 Thus, the significance of AQR stems from: a) the need for a holistic approach to asset quality issues in the banking system, facilitated by CRILC; b) decision to rationalise the concept of regulatory forbearance to minimise the impact of embedded moral hazard; c) an understanding that marginal deterioration in asset quality on an accumulated basis will accentuate the probability of default by a borrower and that early recognition will lead to optimal solutions and d) the belief that given the low credit to GDP ratio and the high potential for credit and consumption growth, it was necessary to encourage the banking industry to overcome legacy issues and make a fresh start on a new and sustainable path. Above all, the philosophy behind AQR is that while the classification of NPAs is based on accounting norms, the proportion of NPAs in a credit portfolio by itself does not give complete information about the inherent quality of the credit portfolio. AQR thus intends to make banks reassess the credit risk of their asset portfolios by moving beyond accounting implications. While AQR has resulted in unprecedented pressure on the profitability of some banks in the short term, the push towards cleaning up of banks’ balance sheets is expected to improve their market valuations through a greater trust in accounting numbers, augment their capacity to lend more and support the economic growth in the medium to long run. 3.10 Subsequently, in view of the build-up of high concentration of credit risk at the system level resulting from individual banks’ large exposures to some of the large corporate entities, the Reserve Bank has proposed a simple ‘Large Exposures (LE) Framework’16, to supplement the risk-based capital framework for banks. The framework proposes additional risk weight and higher provisioning for standard assets with respect to large lending exposure to a single borrower, from the financial year 2017-18 onwards. 3.11 In order to further strengthen the lenders’ ability to deal with stressed assets, the Reserve Bank has formulated guidelines on a ‘Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A)17’ as an optional framework for the resolution of large stressed accounts, which envisages determination of the sustainable debt level for a stressed borrower and bifurcation of the outstanding debt into sustainable debt and equity/quasi-equity instruments. This will help in putting real assets back on track by another avenue for reworking the financial structure of entities facing genuine difficulties, while providing upside to the lenders when the borrower turns around. Evolving insolvency and resolution frameworks 3.12 An effective legal framework for timely resolution of insolvency and bankruptcy will support the development of credit markets, encourage entrepreneurship, improve ease of doing business, and facilitate more investments leading to higher economic growth and development. The enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code 2016 is likely to further help banks in early resolution of problem assets (Box 3.1). Box 3.1: The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code 2016 With the assent of the President of India in May 2016, ‘The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016’ (IBC, 2016) has been enacted and notified in the Gazette of India18. The IBC, 2016 thus becomes a single law that deals with insolvency and bankruptcy - consolidating and amending various laws relating to reorganisation and insolvency resolution. The IBC covers individuals, companies, limited liability partnerships, partnership firms and other legal entities as may be notified, except the financial service providers and is aimed at creating an overarching framework to make it easier for sick companies to either wind up their businesses or engineer a turnaround, and for investors to exit. Salient features of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code • The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (the Code) provides for a clear, coherent and speedy process for early identification of financial distress and resolution of companies and limited liability entities if the underlying business is found to be viable. Under the provisions of the Code, insolvency resolution can be triggered at the first instance of default and the process of insolvency resolution has to be completed within stipulated time limit. • For individuals, the Code provides for two distinct processes, namely – “Fresh Start” and “Insolvency Resolution” and lays down the eligibility criteria for the debtor for the purposes of making an application for a “fresh start” process. • The National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) and the Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) are designated as the adjudicating authorities for corporate persons and firms and individuals, respectively, for resolution of insolvency, liquidation and bankruptcy. • The Code also provides for establishing the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India for regulation of insolvency professionals, insolvency professional agencies and information utilities. • Insolvency professionals will assist in the completion of insolvency resolution, liquidation and bankruptcy proceedings envisaged in the Code. Insolvency professional agencies will develop professional standards, code of ethics and will be first level regulators for insolvency professionals leading to the development of a competitive industry for such professionals. Information utilities will collect, collate, authenticate and disseminate financial information to facilitate such proceedings. • The Code also proposes to establish a fund (the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Fund of India) for the purposes of insolvency resolution, liquidation and bankruptcy of persons. 3.13 The resolution mechanism for financial entities needs to be dealt with separately. Several steps have been taken towards achieving the desired objective in this regard, in line with broad guidelines laid down by the Financial Stability Board (FSB). A working group on resolution regime for financial institutions which submitted its report in May 2014 recommended the setting up of a Financial Resolution Agency (FRA) by either transforming the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC) into FRA or by setting up a new authority that will subsume DICGC. In order to support the establishment of a Resolution Corporation (RC), the Government set up a task force in September 201419. As a sequel to these attempts, the union budget 2016-17 proposed a comprehensive ‘Code on Resolution of Financial Firms’ to provide a specialised resolution mechanism to deal with bankruptcy situations in banks, insurance companies and other financial sector entities. A committee was set up in March 2016 by Government to bring out a draft Code on the Resolution of Financial Firms. Need for strengthening collateral management by banks 3.14 The discussion around the rising levels of stressed assets in the banking sector (especially the PSBs), has also brought to the fore certain weaknesses in the collateral management frameworks of PSBs. A poor performance on recovery of a significant part of impaired loans may largely be on account of deficiencies in collateral management, including instances of inadequate security cover, pledge / hypothecation of the same security to multiple lenders, fraudulent documentation, multiple funding and over-valuation. In cases of consortium and multiple bank financing, some of the banks tend to depend largely on the assessment done by the lead bank or the bank having largest exposure. As most of the PSBs do not have a centralised database for monitoring of collaterals, the task is often left to the largely over-burdened branches, thus adversely affecting efficiency of monitoring process. An IT-enabled integrated collateral management framework including a robust centralised database on collaterals may help banks in not only monitoring the collaterals on an ongoing basis but also detect the incipient cases of frauds in time. 3.15 The Central Registry of Securitisation Asset Reconstruction and Security Interest of India (CERSAI) is emerging as an important component of Indian financial market infrastructure that has a potential to go a long way in supporting the much needed credit risk management of banks and other financial institutions. An Immovable Asset Registry under the aegis of CERSAI has been operational since 2011. Recently, CERSAI has also been entrusted with the responsibility of supporting a robust movable asset registry. Additionally, CERSAI has been notified as the central know your customer (KYC) registry. Given the importance of collateral and KYC registries for sound credit risk management of banks and financial institutions and their role in promoting the financial inclusion especially of the micro and small enterprises and the poor, the role of CERSAI is critical. Encouraging bond financing 3.16 Under the new liquidity norms and in the absence of a vibrant market for securitisation and interest rate derivatives, banks are naturally constrained in extending long term financing. However, given the huge demand-supply gap for infrastructure financing in India, the market for long term corporate debt will continue to depend on banks and other designated specialised development financial institutions for various kinds of support including extending credit enhancements to such debt issuances.20 The Reserve Bank has permitted banks to provide partial credit enhancement to bonds issued for funding infrastructure and other types of projects by companies/special purpose vehicles (SPVs) subject to prudential limits21. Further, Indian companies have also been permitted to issue rupee denominated offshore bonds often referred to as ‘masala’ bonds. Financing needs of micro, small and medium enterprises 3.17 Given the importance of the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) for India’s economy, the financing needs of this sector will continue to command special attention (Chart 3.3). 3.18 A typical role for banks in mature markets is to originate loans and then distribute them to other willing players. In this context, it is necessary to overcome the post-crisis securitisation-stigma. In view of the inherent heterogeneity of MSMEs and relatively constrained availability of credit information, it may be more difficult to achieve a necessary level of disintermediation in the case of MSME financing. A centralised and shared database of MSMEs capturing all available data can help in resolving inherent information asymmetry problems associated with MSME lending, enabling efficiency in assessing the creditworthiness of the underlying MSME loans in securitisation.  3.19 In this context, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has encouraged a framework for a separate exchange/platform for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) thereby facilitating fund raising from the capital market and listing of securities. While there are 104 small companies listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) and eight companies listed on the National Stock Exchange (NSE)23, active trading is seen in very few stocks. In addition, various credit guarantee schemes of the government, also provide supporting mechanisms for the financing needs of MSMEs. Although well-structured and properly funded credit guarantee schemes, boost economic activity while maintaining credit quality, there is a need for rationalising and regulating such schemes (Box 3.2). Box 3.2: Regulation of credit guarantee schemes The Government of India has launched a number of credit guarantee schemes- Credit Guarantee Scheme for Micro and Small Enterprises (CGTMSE), Credit Risk Guarantee Fund Trust for Low Income Housing (CRGFTLIH), Credit Guarantee Fund Scheme for Educational Loans (CGFSEL) and Credit Guarantee Fund Scheme for Skill Development (CGSSD) to aid higher credit flow from formal credit channels to certain targeted beneficiaries. In order to consolidate the operations of various such credit guarantee schemes and thus benefit from the economies of scale, the Government of India set up the National Credit Guarantee Trustee Company (NCGTC). In addition, some of the state governments have also proposed implementing credit guarantee schemes, thereby leading to a fast growing credit guarantee ecosystem in the country. With several such schemes being launched, there may be a need for a proper regulatory framework and supervisory oversight to ensure that their objectives are achieved without resulting in a build-up of huge leverage and contingent fiscal liabilities for the government. When a credit guarantee scheme is not appropriately designed and implemented, it would lead to deterioration in credit quality and failure in achieving its objectives. A robust regulatory set-up for the credit guarantee schemes will broadly ensure: i) proper design of the guarantee schemes; ii) risk based pricing of guarantees; iii) proper rules for leverage, solvency, minimum capital requirements, and caps on pay-out ratio; iv) minimum requirements with regard to governance, risk management and internal controls and v) minimum customer service standards. Regulation of guarantee schemes will contribute to the credibility of the schemes, and efficient use of resources in cases where the schemes are supported by public resources. With proper regulations, guarantee products could become more market-oriented in their design and be less in the nature of social instruments, thus creating space for private credit guarantee companies to enter the market and bring in differentiated products and international best practices to the credit guarantee ecosystem. 3.20 With a view to specifically addressing the issue of delayed payments to the MSME sector, the Reserve Bank conceptualised the Trade Receivables Discounting System (TReDS) as an authorised electronic platform to facilitate discounting of invoices/bills of exchange of MSMEs. Other significant initiatives of the Government of India - ‘Make in India’, ‘Skill India Mission’, ‘Start up India’, ‘Stand up India’ and ‘Digital India’ are also expected to provide a further push to the sector. Financial inclusion 3.21 While debates continue on whether financial inclusion and financial stability are substitutes or complements24, there is no gainsaying the fact that under-penetration of financial services contribute to social instability and hinder financial development. Hence India accords utmost importance to financial inclusion. A committee25 was constituted with the objective of working out a medium-term (five year) measurable action plan for financial inclusion (Box 3.3). The recommendations of the committee along with the suggestions and comments received from the public are being reviewed for implementation. Also the Financial Inclusion Advisory Committee was reconstituted with renewed focus towards ensuring effective implementation of policies laid down for financial inclusion from time to time. 3.22 Financial inclusion plans (FIPs) submitted by banks which are duly approved by their boards form a part of banks’ business strategies. Comprehensive FIPs capture data relating to progress based on various parameters including basic savings bank deposit accounts (BSBDAs), small credits and business correspondent-information and communication technology (BC-ICT) transactions. Box 3.3: Major recommendations of the committee on medium-term path on financial inclusion • Introduction of a welfare scheme-‘Sukanya Shiksha’, for girl child with a view to linking education with banking habits and promoting gender inclusion. • Low-cost solutions based on mobile technology for enhancing the effectiveness of last mile delivery and also facilitating usage. • Phasing out of the interest subvention scheme and ploughing the amount into a very low premium universal crop insurance. • Opening specialised interest-free windows in banks with simple products like demand deposits, agency and participation securities and offering products based on cost-plus financing and deferred payment, deferred delivery contracts to widen inclusion. • Instituting professional credit intermediaries / advisors for MSMEs to help bridge the information gap and thereby help banks take better credit decisions. • Creating a registry for business correspondents (BCs) and encouraging BC certification, to enhance quality of last mile service delivery. • Inter-operability for pre-paid instruments and mobile transactions. • Maximum possible government-to-person (G2P) payments through the banking channel, which will necessitate greater engagement by the government in the financial inclusion drive. • Strengthening the financial literacy centre (FLC) network and complaint / grievance redressal mechanism by leveraging technology to ensure SMS-based acknowledgement of complaints. • Strengthening the information management system to facilitate monitoring of progress of various financial inclusion schemes at the district level. 3.23 There was a considerable increase in the opening of BSBDAs during the year because of the government’s initiative under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), along with a steady growth in small credits and BC-ICT transactions, Kisan Credit Cards (KCCs) and General Credit Cards (GCCs) (Chart 3.4). By improving the frequency and value of operations and balances in these accounts, banks may leverage their efforts in this regard to push their business growth. This drive towards financial inclusion will result in overall economic growth benefitting from synergies with other initiatives like direct benefit transfer of subsidies and curbing the use of cash in the economy. Non-banking financial companies 3.24 Non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) have been playing an important role in the Indian financial sector and this role assumes even greater significance at a time when banking institutions are focusing on cleaning up their balance sheets. In the current context, NBFCs can support the drive towards promoting inclusive growth, by catering to diverse financial needs, especially of MSMEs and individuals.  3.25 With the introduction of differentiated banking licences for setting up of payments banks (PBs) and small finance banks (SFBs) along with the push for an on-tap licencing regime for universal banks, the landscape of the banking industry is expected to undergo significant changes, going forward. While the impact of these changes will begin to emerge only after some of the newly licenced entities including PBs and SFBs start operating, the process itself is heralding a churning in various categories of financial entities, mainly NBFCs including the micro finance institutions (MFIs). Alongside these changes, the revised regulatory framework for NBFCs26 is also being phased in, which seeks to tighten the prudential norms applicable to deposit-accepting NBFCs (NBFC-D) and systemically important non-deposit accepting NBFCs (NBFC-ND-SI) and aligning asset classification norms with those applicable to banks. Thus, while focusing supervisory attention on entities which accept deposits and/or access public funds as also those that are systemically important, the regulations have been rationalised and liberalised to allow a greater operational freedom for other NBFCs. 3.26 In view of the continued importance of ensuring timely flow of funds to the infrastructure sector, the Government of India has set up the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) in the nature of an alternative investment fund (AIF). In addition, a separate category of NBFCs, called NBFC-infrastructure debt fund (NBFC-IDF) has been created. The NBFC-IDFs have also been permitted to raise funds through shorter tenor bonds and commercial papers (CPs) from the domestic market up to 10 per cent of their total outstanding borrowings. Payment and settlement systems 3.27 One of the major aspects of the Reserve Bank’s vision for payment and settlement systems is to proactively encourage electronic payment systems for ushering in a less-cash society. The systemically big payment systems – real time gross settlement (RTGS) and Clearing Corporation of India Limited (CCIL) account for a major share in aggregate transaction volumes under the payment systems (Chart 3.5). Unified payment interface (UPI) 3.28 The ‘Unified Payment Interface (UPI)’, launched by the Reserve Bank in April 2016, is a next generation online payment solution initiative by National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI). The solution leverages on the growing use of smart phones, availability of interfaces in local languages and wide access to internet and data. The solution has been built on the Immediate Payment Service (IMPS) platform which has seen rapid growth in the last few years (Chart 3.6). 3.29 UPI facilitates online transactions with features such as a single-click, two-factor authentication for transactions, virtual address as a payment identifier for transferring and receiving money, merchant payment using single application, scheduling pull and push payments for various purposes- utility bills, over the counter payments and barcode based payments. It enhances customer experience by way of easy accessibility, secured virtual identifier and use of single application for multiple bank accounts. In essence, UPI is a digital disruptive innovation which is not only expected to be a game changer for e-commerce businesses, but will also help banks provide better customer service apart from providing them an opportunity to enter into a niche area of business broadly dominated by mobile wallets. Cyber resilience in payment systems27 3.30 With increasing migration towards alternate modes of payment, resilience of payment systems, particularly cyber resilience, is critical for continued confidence in payment systems. For ensuring that critical services continue to operate, service providers should carry out risk analyses of primary and secondary sites to ensure that the secondary site is not generally affected by an event that affects the primary site. Prevention measures for cyber resilience include identification of risks, raising awareness within an organisation, implementing layered systems and system components, using anti-virus solutions, minimising access points to the system, adopting secure coding standards, undertaking security audits and penetration testing, preventing unauthorised access and tightening infrastructure controls. Cyber resilience is an enterprise wide issue and internal auditors can play a significant role in confirming the efficacy of cyber risk initiatives and policies.

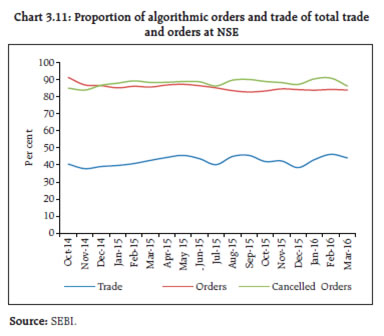

Capital markets Primary market 3.31 The amount raised through public issuance of equity and debt increased in 2015-16 (Chart 3.7). The proportion of amount raised through the qualified institutional placements (QIPs) and preferential allotments continued to be high (Chart 3.8). 3.32 The market for corporate bond issuances in India is characterised by the predominance of private placements as against public issues (Chart 3.9). Private placement issues are usually offered to a few select investors like qualified institutional buyers (QIBs), high net worth individuals (HNIs) or through arrangers over-the-telephone market and are then listed on the stock exchanges. 3.33 As the private placement mechanism may lack transparency in price discovery, SEBI has laid down a framework for issuance of debt securities on private placement basis through an electronic book mechanism. To start with, the electronic book mechanism is mandatory for all private placements of debt securities in primary markets with issue size of ₹ 5 billion and above, inclusive of the green shoe option, if any, with all recognised stock exchanges being eligible to act as electronic book providers (EBPs). The key benefits of an electronic book vis-à-vis over-the-telephone market, inter-alia, are improvements in efficiency, transparency in price discovery and a reduction in cost and time taken for such issuances.