|

3.1 Globally, the story of banking has much in common, as it evolved with the moneylenders accepting deposits and issuing receipts in their place. According to the Central Banking Enquiry Committee (1931), money lending activity in India could be traced back to the Vedic period, i.e., 2000 to 1400 BC. The existence of professional banking in India could be traced to the 500 BC. Kautilya’s Arthashastra, dating back to 400 BC contained references to creditors, lenders and lending rates. Banking was fairly varied and catered to the credit needs of the trade, commerce, agriculture as well as individuals in the economy. Mr. W.E. Preston, member, Royal Commission on Indian Currency and Finance set up in 1926, observed “....it may be accepted that a system of banking that was eminently suited to India’s then requirements was in force in that country many centuries before the science of banking became an accomplished fact in England.”1 An extensive network of Indian banking houses existed in the country connecting all cities/towns that were of commercial importance. They had their own inland bills of exchange or hundis whichwere the major forms of transactions between Indian bankers and their trans-regional connections.

2 Banking practices in force in India were vastly different from the European counterparts. The dishonoring of hundis was a rare occurrence. Most banking worked on mutual trust, confidence and without securities and facilities that were considered essential by British bankers. Northcote Cooke observed “....the fact that Europeans are not the originators of banking in this country does not strike us with surprise. ”3 Banking regulation also had a rich tradition and evolved along with banking in India. In fact, the classic ‘Arthashastra’ also had norms for banks going into liquidation. If anyone became bankrupt, debts owed to the State had priority over other creditors (Leeladhar, 2007).

3.2 The pre-independence period was largely characterised by the existence of private banks organised as joint stock companies. Most banks were small and had private shareholding of the closely held variety. They were largely localised and many of them failed. They came under the purview of the Reserve Bank that was established as a central bank for the country in 1935. But the process of regulation and supervision was limited by the provisions of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and the Companies Act, 1913. The indigenous bankers and moneylenders had remained mainly isolated from the institutional part of the system. The usurious network was still rampant and exploitative. Co-operative credit was the only hope for credit but the movement was successful only in a few regions.

3.3 The early years of independence (1947 to 1967) posed several challenges with an underdeveloped economy presenting the classic case of market failure in the rural sector, where information asymmetry limited the foray of banks. Further, the non-availability of adequate assets made it difficult for people to approach banks. With the transfer of undertaking of Imperial Bank of India to State Bank of India (SBI) and its subsequent massive expansion in the under-banked and unbanked centres spread institutional credit into regions which were un-banked heretofore. Proactive measures like credit guarantee and deposit insurance promoted the spread of credit and savings habits to the rural areas. There were, however, problems of connected lending as many of the banks were under the control of business houses.

3.4 The period from 1967 to 1991 was characterised by major developments, viz., social control on banks in 1967 and nationalisation of 14 banks in 1969 and six more in 1980. The nationalisation of banks was an attempt to use the scarce resources of the banking system for the purpose of planned development. The task of maintaining a large number of small accounts was not profitable for the banks as a result of which they had limited lending in the rural sector. The problem of lopsided distribution of banks and the lack of explicit articulation of the need to channel credit to certain priority sectors was sought to be achieved first by social control on banks and then by the nationalisation of banks in 1969 and 1980. The Lead Bank Scheme provided the blue-print of further bank branch expansion. The course of evolution of the banking sector in India since 1969 has been dominated by the nationalisation of banks. This period was characterised by rapid branch expansion that helped to draw the channels of monetary transmission far and wide across the country. The share of unorganised credit fell sharply and the economy seemed to come out of the low level of equilibrium trap. However, the stipulations that made this possible and helped spread institutional credit and nurture the financial system, also led to distortions in the process. The administered interest rates and the burden of directed lending constrained the banking sector significantly. There was very little operational flexibility for the commercial banks. Profitability occupied a back seat. Banks also suffered from poor governance. The financial sector became the ‘Achilles heel’ of the economy (Rangarajan, 1998). Fortunately, for the Indian economy, quick action was taken to address these issues.

3.5 The period beginning from the early 1990s witnessed the transformation of the banking sector as a result of financial sector reforms that were introduced as a part of structural reforms initiated in 1991. The reform process in the financial sector was undertaken with the prime objective of having a strong and resilient banking system. The progress that was achieved in the areas of strengthening the regulatory and supervisory norms ushered in greater accountability and market discipline amongst the participants. The Reserve Bank made sustained efforts towards adoption of international benchmarks in a gradual manner, as appropriate to the Indian conditions, in various areas such as prudential norms, risk management, supervision, corporate governance and transparency and disclosures. The reform process helped in taking the management of the banking sector to the level, where the Reserve Bank ceased to micro-manage commercial banks and focused largely on the macro goals. The focus on deregulation and liberalisation coupled with enhanced responsibilities for banks made the banking sector resilient and capable of facing several newer global challenges.

3.6 In the above backdrop, this chapter traces the history of the banking sector in India. Although the focus is on its post-independence history, it starts with a broad brush sketch of the early years of banking. The chapter is organised in six sections. Section II narrates the story as it unfolded historically in the pre-independence period. Section III outlines the major developments in the banking sector from 1947 to 1967. Section IV deals at length with the major developments in the period from 1967 to 1991. Developments from 1991 and onwards are covered in Section V. Section VI sums up the main points of discussions.

II. THE EARLY PHASE OF BANKING IN INDIA –UP TO 1947

Beginning of Banking in India

3.7 The phase leading up to independence laid the foundations of the Indian banking system. The beginning of commercial banking of the joint stock variety that prevailed elsewhere in the world could be traced back to the early 18th century. The western variety of joint stock banking was brought to India by the English Agency houses of Calcutta and Bombay (now Kolkata and Mumbai). The first bank of a joint stock variety was Bank of Bombay, established in 1720 in Bombay4 . This was followed by Bank of Hindustan in Calcutta, which was established in 1770 by an agency house.5 This agency house, and hence the bank was closed down in 1832. The General Bank of Bengal and Bihar, which came into existence in 1773, after a proposal by Governor (later Governor General) Warren Hastings, proved to be a short lived experiment6 . Trade was concentrated in Calcutta after the growth of East India Company’s trading and administration. With this grew the requirement for modern banking services, uniform currency to finance foreign trade and remittances by British army personnel and civil servants. The first ‘Presidency bank’ was the Bank of Bengal established in Calcutta on June 2, 1806 with a capital of Rs.50 lakh. The Government subscribed to 20 per cent of its share capital and shared the privilege of appointing directors with voting rights. The bank had the task of discounting the Treasury Bills to provide accommodation to the Government. The bank was given powers to issue notes in 1823. The Bank of Bombay was the second Presidency bank set up in 1840 with a capital of Rs.52 lakh, and the Bank of Madras the third Presidency bank established in July 1843 with a capital of Rs.30 lakh. They were known as Presidency banks as they were set up in the three Presidencies that were the units of administrative jurisdiction in the country for the East India Company. The Presidency banks were governed by Royal Charters. The Presidency banks issued currency notes until the enactment of the Paper Currency Act, 1861, when this right to issue currency notes by the Presidency banks was abolished and that function was entrusted to the Government.

3.8 The first formal regulation for banks was perhaps the enactment of the Companies Act in 1850. This Act, based on a similar Act in Great Britain in 1844, stipulated unlimited liability for banking and insurance companies until 1860, as elsewhere in the world. In 1860, the Indian law permitted the principle of limited liability following such measures in Britain. Limited liability led to an increase in the number of banking companies during this period. With the collapse of the Bank of Bombay, the New Bank of Bombay was established in January 1868.

3.9 The Presidency Bank Act, which came into existence in 1876, brought the three Presidency banks under a common statute and imposed some restrictions on their business. It prohibited them from dealing with risky business of foreign bills and borrowing abroad for lending more than 6 months, among others. In terms of Act XI of 1876, the Government of India decided on strict enforcement of the charter and the periodic inspection of the books of these banks. The proprietary connection of the Government was, however, terminated, though the banks continued to hold charge of the public debt offices in the three presidency towns, and the custody of a part of the Government balances. bank established in July 1843 with a capital of Rs.30 lakh. They were known as Presidency banks as they were set up in the three Presidencies that were the units of administrative jurisdiction in the country for the East India Company. The Presidency banks were governed by Royal Charters. The Presidency banks issued currency notes until the enactment of the Paper Currency Act, 1861, when this right to issue currency notes by the Presidency banks was abolished and that function was entrusted to the Government.

AND FINANCE

The Act also stipulated the creation of Reserve Treasuries at Calcutta, Bombay and Madras into which sums above the specified minimum balances promised to the presidency banks, were to be lodged only at their head offices. The Government could lend to the presidency banks from such Reserve Treasuries. This Act enabled the Government to enforce some stringent measures such as periodic inspection of the books of these banks. The major banks were organised as private shareholding companies with the majority shareholders being Europeans.

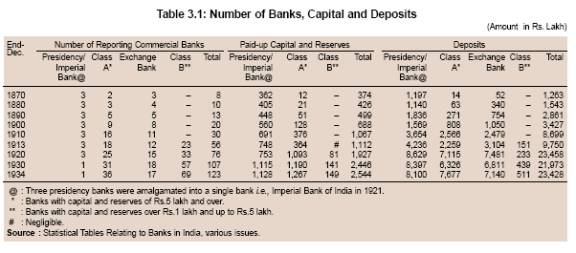

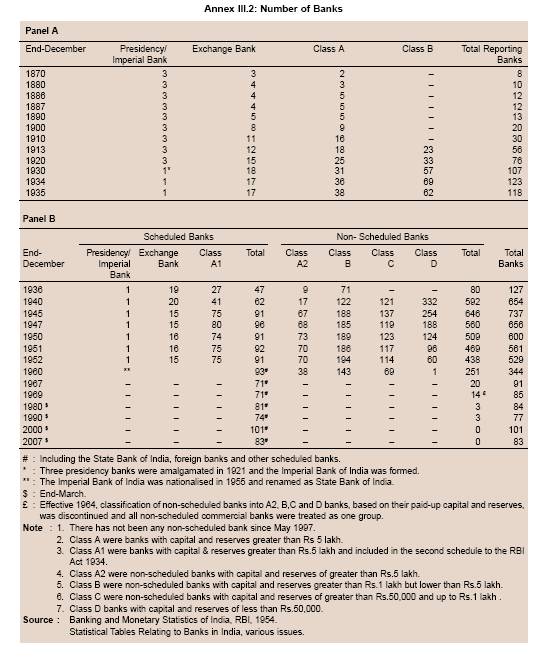

3.10 The first Indian owned bank was the Allahabad Bank set up in Allahabad in 1865, the second, Punjab National Bank was set up in 1895 in Lahore, and the third, Bank of India was set up in 1906 in Mumbai. All these banks were founded under private ownership. The Swadeshi Movement of 1906 provided a great impetus to joint stock banks of Indian ownership and many more Indian commercial banks such as Central Bank of India, Bank of Baroda, Canara Bank, Indian Bank, and Bank of Mysore were established between 1906 and 1913. By the end of December 1913, the total number of reporting commercial banks in the country reached 56 comprising 3 Presidency banks, 18 Class ‘A’ banks (with capital of greater than Rs.5 lakh), 23 Class ‘B’ banks (with capital of Rs.1 lakh to 5 lakh) and 12 exchange banks. Exchange banks were foreign owned banks that engaged mainly in foreign exchange business in terms of foreign bills of exchange and foreign remittances for travel and trade. Class A and B were joint stock banks. The banking sector during this period, however, was dominated by the Presidency banks as was reflected in paid-up capital and deposits (Table 3.1).

3.11 The Swadeshi Movement also provided impetus to the co-operative credit movement and led to the establishment of a number of agricultural credit societies and a few urban co-operatives. The evolution of co-operative banking movement in India could be traced to the last decade of the 19th Century. The late Shri Vithal L Kavthekar pioneered the urban co-operative credit movement in the year 1889 in the then princely State of Baroda.7 The first registered urban co-operative credit society was the Conjeevaram Urban Co-operative Bank, organised in Conjeevaram, in the then Madras Presidency. The idea of setting up of such a co-operative was inspired by the success of urban co-operative credit institutions in Germany and Italy. The second urban co-operative bank was the Peoples’ Co-operative Society in 1905 in Bangalore city in the princely State of Mysore. The joint stock banks catered mainly to industry and commerce. Their inability to appreciate and cater to the needs of clientele with limited means effectively drove borrowers to moneylenders and similar agencies for loans at exorbitant rates of interest - this situation was the prime mover for non-agricultural credit co-operatives coming into being in India. The main objectives of such co-operatives were to meet the banking and credit requirements of people with smaller means to protect them from exploitation. Thus, the emergence of urban co-operative banks’ was the result of local response to an enabling legislative environment, unlike the rural co-operative movement that was largely State-driven (Thorat, 2006).

3.12 After the early recognition of the role of the co-operatives, continuous official attention was paid to the provision of rural credit. A new Act was passed in 1912 giving legal recognition to credit societies and the like. The Maclagan Committee, set up to review the performance of co-operatives in India and to suggest measures to strengthen them, issued a report in 1915 advocating the establishment of provincial cooperative banks. It observed that the 602 urban cooperative credit societies constituted a meager 4.4 per cent of the 13,745 agricultural credit societies. The Committee endorsed the view that the urban cooperative societies were eminently suited to cater to the needs of lower and middle-income strata of society and such institutions would inculcate banking habits among middle classes.

3.13 Apart from commercial and co-operative banks, several other types of banks existed in India. This was because the term “bank” was an omnibus term and was used by the entities, which, strictly speaking, were not banks. These included loan companies, indigenous bankers and nidhis some of which were registered under the Companies Act, 1913. Although very little information was available about such banks, their number was believed to be very large. Even the number of registered entities was enormous. Many doubtful companies registered themselves as banks and figured in the statistics of bank failures. Consequently, it was difficult to define in strict legal terms the scope of organised banking, particularly in the period before 1913 (Chandavarkar, 2005).

World War I and its Impact on Banking in India

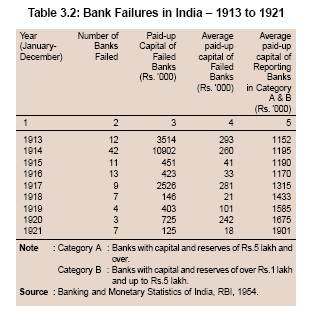

3.14 The World War I years (1913 to 1918) were indeed difficult years for the world economy. The alarming inflationary situation that had developed as a result of war financing and concentration on the war led to other problems like neglect of agriculture and consumers. Most activity during the war period was concentrated in urban areas. This further tilted the already adverse urban-rural balance. Rural areas lacked access to organised banking and this led to almost complete dependence of farmers on moneylenders who charged exorbitant rates of interest. During the war period, a number of banks failed. Some banks that failed had combined trading functions with banking functions. More importantly, several of the banks that failed had a low capital base. For instance, average capital of failed banks in 1913 was Rs.2.9 lakh as against the average capital of Rs.12 lakh for the category of Class A and B banks. The crisis had begun before the World War I, but accentuated during it (Table 3.2).

3.15 Most of these banks had also maintained an unduly low proportion of cash and other liquid assets. As a result, they were not resilient enough to be able to perform under difficult times. There were also some big banks that failed, such as Indian Specie Bank, a British bank with a paid-up capital of Rs.75.6 lakh. It failed not due to low capital, but due to its involvement in silver speculation (Tandon, 1988).

3.16 In retrospect, bank failures in India were attributed by scholars and committees, in a large measure, to individual imprudence and mismanagement, fraudulent manipulation by directors and managers; and incompetence and inexperience. Many banks had granted a large amount of unsecured advances to directors and their companies. The absence of adequate regulatory safeguards made it easy for directors and managers to mislead depositors/shareholders. It underscored the need for suitable machinery for regulation of commercial banking in India. Several exchange banks also failed during this period mainly due to external reasons relating to their parent countries/companies. The mor tality rate among exchange banks was disconcertingly high. The commonest causes of failure of exchange banks were global, the highs and lows of the World Wars and inflation.

3.17 Interestingly, the co-operatives presented a somewhat different picture primarily because these organisations were based on mutual trust and had effective control by its member owners. The member depositors had confidence in the working of cooperatives because of their small size. There was a phenomenon of flight of deposits from joint stock banks to urban co-operative banks. The Maclagan Committee that investigated the crisis stated “as a matter of fact, the crisis had a contrary effect and in most provinces there was a movement to withdraw deposits from non-co-operative institutions and place them in cooperative institutions. The distinction between the two classes of security was well appreciated and preference given to the co-operatives due partly to the local character, but mainly to the connection of Government with the co-operative movement” (Thorat, 2006).

3.18 The presidency banks were amalgamated into a single bank, the Imperial Bank of India, in 1921.8 The Imperial Bank of India was further reconstituted with the merger of a number of banks belonging to old princely states such as Jaipur, Mysore, Patiala and Jodhpur. The Imperial Bank of India also functioned as a central bank prior to the establishment of the Reserve Bank in 1935. Thus, during this phase, the Imperial Bank of India performed three set of functions, viz., commercial banking, central banking and the banker to the government.

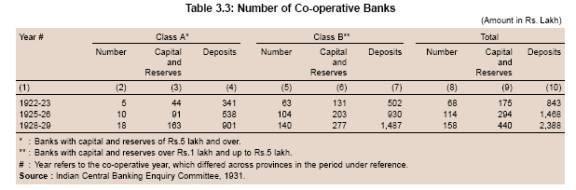

3.19 By 1930, the number of commercial banks increased to 107 with the Imperial Bank of India still dominating the Indian banking sector (refer Table 3.1). Besides, at end-March 1929, 158 co-operative banks also existed. The number of co-operative banks rose sharply (more than doubled) between 1922-23 to 1928-29 (Table 3.3). Although greater than commercial banks in number, the size of deposits of co-operative banks was much smaller.

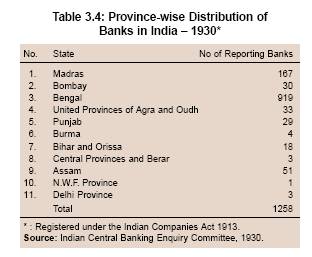

3.20 In 1930, the banking system, in all, comprised 1258 banking institutions registered under the Indian Companies Act, 1913 (Table 3.4).

3.21 Of the 1258 entities registered as banks in 1930, while some were banks in genuine terms, others were indigenous banks, nidhis and loan companies. In a large number of towns and villages, indigenous banks were the main source of credit. According to the Indian Central Banking Enquiry Committee, “a certain number of indigenous bankers work along modern lines and transact all kinds of business which the ordinary joint-stock banks transact, including the issue of pass books and cheque books.” They did not publish balance sheets and were managed by proprietors. Some of these, such as ‘Bank of Chettinad’ were registered under the Indian Companies Act. However, there were other smaller banks that did not register themselves.

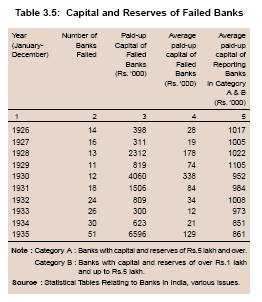

3.22 The world economy was gripped by the Great Depression during the period from 1928 to 1934. This also had an impact on the Indian banking industry with the number of banks failing rising sharply due to their loans going bad. The capital of banks that failed, on an average, was lower than the average size of the capital of reporting banks in categories A and B, indicating that the banks that failed were small (Table 3.5).

3.23 The Indian Central Banking Enquiry Committee, which was set up in 1929 to survey extensively the problems of Indian banking, observed that a central bank be established for the country and that a special Bank Act be enacted incorporating relevant provisions of the then existing Indian Companies Act (1913), and including new provisions relating to (i) organisation, (ii) management, (iii) audit and inspection, and (iv) liquidation and amalgamations. It also noted that the commercial banks played a negligible role in financing the requirements of agricultural production and cooperative credit .9 Examining the credit requirements of the cultivator, it noted “his needs are satisfied, if at all, inadequately and at ruinous prices”. In an agrarian economy, like India at that time, credit to agriculture was very crucial. Bank credit to agriculture was 0.3 per cent of GDP. Rural indebtedness in 1931 was estimated at Rs.900 crore, and it was increasing due to past indebtedness; extravagant social and ceremonial expenditure; high interest rates; recurring losses of cattle due to drought and disease; and lease of land at high prices and high rentals, resulting in the transfers of land from farmers to moneylenders.

3.24 The lack of spread of banking in rural areas and the consequent dependence of the rural population on informal sources was a major concern during these times. The problem of rural credit to some extent was also due to the fact that there was no distinction of the type of credit dispensed and the term for which it was granted. Bigger amounts of loans taken for investment purposes were unlikely to be paid off in a single season. It was reported that in many provinces, credit overdues to credit co-operative institutions constituted 60 to 70 per cent of the outstanding principal due.10

Setting up of the Reserve Bank and its Role

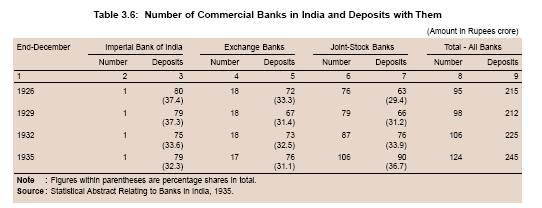

3.25 The setting up of a central bank for the country was recommended by various committees that went into the causes of bank failures.11 It is interesting to note that many central banks were established specifically to take care of bank failures. For instance, the US Federal Reser ve, was established in 1913 pr imarily against the background of recurrent banking crises. It was felt that the establishment of a central bank would bring in greater governance and integrate the loosely connected banking structure in the country. It was also believed that the establishment of a central bank as a separate entity that does not conduct ordinary banking business (like the Imperial Bank of India) was likely to have the stature to be able to deftly handle the central banking functions without the other joint stock banks feeling any rivalry towards it.12 Accordingly, the Reserve Bank of India Act 1934 was enacted paving the way for the setting up of the Reserve Bank of India. The issue of bank failures and the need for catering to the requirements of agriculture were the two prime reasons for the establishment of the Reserve Bank. The banking sector came under the purview of the Reserve Bank in 1935. At the time of setting up of the Reserve Bank, the joint stock banks constituted the largest share of the deposits held by the banking sector, followed by the Imperial Bank of India and exchange banks (Table 3.6).

3.26 The Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 gave the Reserve Bank powers to regulate issue of bank notes, the custody of the commercial banks’ cash reserves and the discretion of granting them accommodation. The preamble to the RBI Act set forth its functions as “to regulate the issue of bank notes and the keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary stability in India and generally to operate the currency and credit system of the country to its advantage”. The Reserve Bank’s main functions could be classified into the following broad categories (a) to act as a banker to the Government; (b) to issue notes; (c) to act as a banker to other banks; and (d) to maintain the exchange ratio. The RBI Act had a limited control on banks although its obligations in each sphere were spelt out in clear terms. There was some amount of built-in flexibility as the Reserve Bank was vested with extra powers and maneuverability under extra-ordinary circumstances, that could be exercised only with the prior approval of the Governor General in Council or the Central Board of the Bank as might be prescribed in each case.

3.27 The Reserve Bank, as the lender-of-last-resort, had a crucial role in ensuring the liquidity of the short-term assets of commercial banks. The banking sector had adequate liquidity in the initial years because it had a facility of selling Government securities freely to the Reserve Bank.13 In 1935, banks were required to maintain cash reserves of 5 per cent of their demand liabilities and 2 per cent of their time liabilities on a daily basis. The task of managing the currency that was assigned to the Controller of Currency came to the Reserve Bank in March 1935 under Section 3 of the RBI Act, 1934. The provisions of the RBI Act also required the Reserve Bank to act as a banker’s bank. In accordance with the general central banking practice, the operations of the Reserve Bank with the money market were to be largely conducted through the medium of member banks, viz., the ‘scheduled’ banks and the provincial co-operative banks. The ‘scheduled’ banks were banks which were included in the Second Schedule to the RBI Act and those banks in British India that subsequently became eligible for inclusion in this Schedule by virtue of their paid-up capital and reserves being more than Rs.5 lakh in the aggregate. The power to include or exclude banks in or from the Schedule was vested with the Governor General in Council. The preamble of the Reserve Bank of India Act that was accepted had no reference to a ‘gold standard currency’ for British India unlike that envisaged in the initial preamble of the 1928 Bill. This change occurred due to the fluidity of the international monetary situation in the intervening period, following Great Britain’s departure from the gold standard in September 1931.

3.28 Some promotional role was envisaged for the Reserve Bank from the very beginning as agricultural credit was a special responsibility of the Reserve Bank in terms of the RBI Act. The Reserve Bank assumed a proactive role in the sphere of agricultural credit for the economy and took concrete action by commissioning two studies in 1936 and 1937 in this area. Almost the entire finance required by agriculture at that time was supplied by moneylenders; cooperatives and other agencies played a negligible part (Mohan, 2004a). During the period from 1935 to 1950, the Reserve Bank continued to focus on agricultural credit by fostering the co-operative credit movement through the provision of financial accommodation to co-operatives. As a result of the concerted efforts and policies of the Reserve Bank, a well-differentiated structure of credit institutions for purveying credit to agriculture and allied activities emerged. Within the short-term structure, primary agricultural credit societies at the village level formed the base level, while district central co-operative banks were placed at the intermediate level, and the State co-operative banks at the apex level. The long-term structure of rural co-operatives comprised State co-operative agriculture and rural development banks at the State level, and primary co-operative agriculture and rural development banks at the decentralised district or block level. These institutions focused on providing typically medium to long-term loans for making investments in agriculture and rural industries.

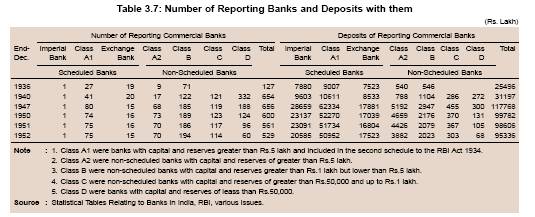

3.29 The central bank, if it is a supervisory authority must have sufficient powers to carry out its functions, such as audit and inspection to be able to detect and restrain unsound practices and suggest corrective measures like revoking or denying licences. However, the Reserve Bank in the earlier years did not have adequate powers of control or regulation. Commercial banks were governed by the Company Law applicable to ordinary non-banking companies, and the permission of the Reserve Bank was not required even for setting up of a new bank. The period after setting up of the Reserve Bank saw increase in the number of reporting banks. The classification of banks was expanded to include the banks with smaller capital and reserve base. Class ‘A’ banks were divided into A1 and A2. Further, two new categories of banks, viz,. ‘C’ and ‘D’ were added to include the smaller banks. Banks with capital and reserves of greater than Rs.5 lakh and included in the second schedule to the RBI Act 1934 were classified as Class A1, while the remaining non-scheduled banks with capital and reserves of greater than Rs.5 lakh were classified as Class A2. The rest of the non-scheduled banks were classified according to their size; those with capital and reserves of greater than Rs.1 lakh and lower than Rs.5 lakh were classified as Class B; banks with capital and reserves of greater than Rs.50,000 and up to Rs.1 lakh were classified as Class C; and those with capital and reserves of less than Rs.50,000 were classified as Class D. In 1940, the number of reporting banks was 654 (Table 3.7).

3.30 The underdeveloped nature of the economy and the lack of an appropriate regulatory framework posed a problem of effective regulation of a large number of small banks. The laisez faire policy that permitted free entry and exit had the virtues of free competition. However, benefits of such a policy are best reaped in a system that is characterised by ‘perfect competition’ unalloyed by market failures and imperfect markets. Indian financial markets at that stage, however, were certainly far from perfect. The free entry ushered in a very high growth of banking companies only to be marred by the problem of massive bank failures. Mushrooming growth of small banks in a scenario, where adequate regulation was not in place, led to various governance issues. The Reserve Bank’s statute alone then did not provide for any detailed regulation of the commercial banking operations for ensuring sound banking practices. The submission of weekly returns made by scheduled banks under Section 42(2) of the Act was mainly intended to keep a watch over their compliance with the requirements regarding maintenance of cash reserves with the Reserve Bank. Inspection of banks by the Reserve Bank was visualised for the limited purpose of determining the eligibility of banks for inclusion or retention in the Second Schedule to the Act. Thus, apart from the limited scope of the Reserve Bank’s powers of supervision and control over scheduled banks, a large number of small banking institutions, known as non-scheduled banks, lay entirely outside the purview of its control. When the Reserve Bank commenced operations, there were very few and relatively minor provisions in the Indian Companies Act, 1913, per taining to banking companies. This virtual absence of regulations for controlling the operations of commercial banks proved a serious handicap in the sphere of its regulatory functions over the banking system. There was ambiguity regarding the functioning of the smaller banks as there was no control on their internal governance or solvency.

3.31 Measures were taken to strengthen the regulation first by amending the Indian Companies Act in 1936. This amendment incorporated a separate chapter on provisions relating to banking companies. Prior to its enactment, banks were governed in all important matters such as incorporation, organisation and management, among others, by the Indian Companies Act, 1913 which applied commonly to banking as well as non-banking companies. There were only certain relatively innocuous provisions in the Companies Act 1913, which made a distinction between banks and other companies. The enactment of the Indian Companies (Amendment) Act, 1936 incorporated a separate chapter on provisions relating to banking companies, including minimum capital and cash reserve requirement and some operational guidelines. This amendment clearly stated that the banking companies were distinct from other companies.

3.32 In order to gradually integrate the non-scheduled banks with the rest of the organised banking, the Reserve Bank continued to make efforts to keep in close touch with the non-scheduled banks and provide them advice and guidance. The Reserve Bank also continued to receive the balance sheets and the cash reserve returns of these banks from the Registrars of Joint Stock Companies. According to the information received from them, in British India as on the 31st December 1938, about 1,421 concerns were operating which might be considered as non-scheduled banks. The real issue was to get them under the regulatory purview of the Reserve Bank because a large number of these companies claimed that they were not really ‘banks’ within the meaning of Section 277(F) of the Companies Act as that section defined a banking company as “a company which carried on as its principal business, the acceptance of deposits subject to withdrawal by cheque, draft, or order”, and they did not accept deposits so withdrawable.

3.33 In order to ensure a viable banking system, it was crucial that the weak links in the banking system were taken care of. For this, it was essential to address the root cause of bank failures, which was then the lack of adequate regulation. Hence, the need was felt to put in place sound regulatory norms. The fact that most of the banks that failed were small and non-scheduled underlined the need for monitoring the operations of the non-scheduled banks regularly. In October 1939, a report on the non-scheduled banks with a special reference to their assets and liabilities was submitted to the Reserve Bank’s Central Board. The report mentioned the low reserves position of these banks and the overextension of advances portfolios and large proportion of bad and doubtful debt. The report stressed the need for comprehensive banking regulation for the country.

3.34 In 1939, the Reserve Bank submitted to the Central Government its proposals for banking legislation in India. The important features of the proposals were to define banking in a simpler and clearer way than had been done in the Indian Companies Act, 1936. Second, the proposals sought to ensure that institutions calling themselves ‘banks’ started with sufficient minimum capital to enable them to operate on a scale large enough to make it possible for them to earn reasonable profits. Third, the proposals visualised certain moderate restrictions on bank investments in order to protect the depositors. Finally, an endeavour was made to expedite liquidation proceedings so that in the event of a bank failing, the depositors were paid off with the minimum delay and expense. However, the Government decided not to under take any comprehensive legislation during the war period when all the energies of the Government were inevitably concentrated on the war effort. Certain interim measures were taken to regulate and control by legislation certain issues that required immediate attention. After the war, the aspect of inadequate regulation was addressed partially by the promulgation of the RBI Companies (Inspection) Ordinance, 1946. New powers were given to the Reserve Bank under the Banking Companies (Restriction of Branches) Act, 1946 and the Banking Companies (Control) Ordinance, 1948. Most of the provisions in these enactments were subsequently embodied in the Banking Companies Act in 1949. This Act gave the Reserve Bank very comprehensive powers of supervision and control over the entire banking system as detailed in the subsequent section.

The World War II and its Impact on Indian Banking

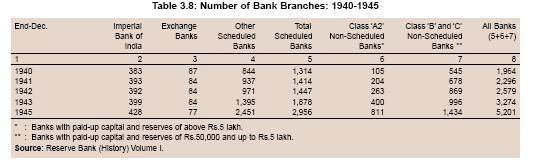

3.35 The effects of the Second World War (1939 to 1944) on Indian banking were far-reaching. As India increasingly became a supply base for the Allied armies in the Middle East and South-East Asia, Government expenditure on defence and supplies to the Allies led to a rapid expansion of currency. As a result, the total money income of some sections of the community rose. This combined with a diversity of causes such as the difficulty in obtaining imports, the diversion of internal supplies to war needs, the control of the channels of investment and the distortion in the pattern of income distribution, among others, led to a rapid increase in the ‘unspent margin’ in the higher income groups, which, in turn, brought about a large pool of bank deposits. Such a situation encouraged the development of banking enterprises, apart from exchange banks, whose performance was driven mainly by external factors. The number of branches increased sharply between 1940 and 1945 and most of this branch expansion was accounted for by scheduled commercial banks (other than Imperial Bank of India and exchange banks) and non-scheduled banks (Table 3.8).

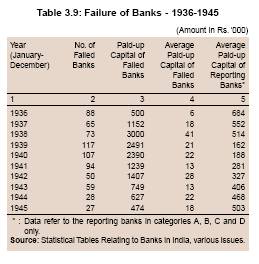

3.36 Several of the banks that expanded had very low capital. For instance, one bank with a capital of less than Rs.2 lakh opened more than 75 branches. The banking system that prevailed, therefore, was freer than the ‘free banking that prevailed in the US around the civil war’. This was because even under the free banking there were some norms regarding entry level capital, and anyone meeting the minimum requirement of integrity and capital could receive a charter. In India, even these entry level requirements were not enforceable. The funds deposited by the public were often utilised to acquire control over non-banking companies by the purchase of their shares at highly inflated prices. Other conspicuous features of these small banks were the cross holding of shares between the banks and other companies in which the management was interested, large unsecured advances to persons connected with the management, advances against speculative shares when prices were very high and advances against immovable property which could not be recovered easily in times of need. Between 1936 and 1945, many small banks failed (Table 3.9).

3.37 Several banks in the process of expansion spread out thin, which increased the risk of failure. Interestingly, in spite of this wave of bank failures, there was very little contagion across the banking sector. This was because the Indian banking sector was underdeveloped and was loosely connected. This lack of integration kept the effect of bank failures fairly localised even when relatively larger banks failed. The resilience of the Indian banking system came to a large measure from the relative isolation of banks and lack of integration of the banking sector. Besides, slower communications in those years paradoxically saved it from a wide spread crisis (Chandavarkar, 2005).

3.38 To sum up, the period leading up to the independence was a difficult period for Indian banks. A large number of small banks sprang up with low capital base, although their exact number was not known. The organised sector consisted of the Imperial Bank of India, joint-stock banks (which included both joint stock English and Indian banks) and the exchange banks dealing in foreign exchange. During this period, a large number of banks also failed. This was due to several factors. This period saw the two world wars and the Great Depression of 1930. Although global factors contributed to bank failure in a large measure, several domestic factors were also at play. Low capital base, insufficient liquid assets and inter-connected lending were some of the major domestic factors. When the Reserve Bank was set up in 1935, the predominant concern was that of bank failures and of putting in place adequate safeguards in the form of appropriate banking regulation. Yet, even after more than twelve years after the establishment of the Reserve Bank, the issue of strengthening of the Reserve Bank through a separate legislation did not come through. The major concern was the existence of non-scheduled banks as they remained outside the purview of the Reserve Bank. Banking was more focused on urban areas and the credit requirements of agriculture and rural sectors were neglected. These issues were pertinent when the country attained independence.

III. BANKING IN THE EARLY YEARS OFINDEPENDENT INDIA - 1947 TO 1967

3.39 When the country attained independence, Indian banking was entirely in the private sector. In addition to the Imperial Bank, there were five big banks, each holding public deposits aggregating Rs.100 crore and more, viz., Central Bank of India Ltd., Punjab National Bank Ltd., Bank of India Ltd., Bank of Baroda Ltd. and United Commercial Bank Ltd. All other commercial banks were also in the private sector and had a regional character; most of them held deposits of less than Rs.50 crore. Interestingly, the Reserve Bank was also not completely State owned until it was nationalised in terms of the Reserve Bank of India (transfer to Public Ownership) Act, 1948.

3.40 Independence made a large difference to many spheres of economic activity and banking was one of the most crucial areas where a phenomenal transformation took place. On the eve of

independence, several difficulties plagued the banking system as noted by the then Governor C.D. Deshmukh:

“The difficulty of the task of the Reserve Bank of India in dealing with the banking system in the country does not lie in the multiplicity of banking units alone. It is aggravated by its diversity and range. There can be no standard treatment in practice although in theory the same law governs all’’.14

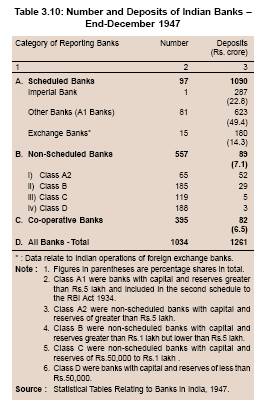

3.41 At the time of independence, the banking structure was dominated by the domestic scheduled commercial banks. Non-scheduled banks, though large in number, constituted a small share of the banking sector (Table 3.10).

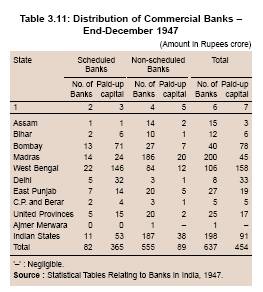

3.42 Commercial banks had a regional focus, as alluded to earlier. West Bengal had the largest number of scheduled commercial banks, followed by Madras and Bombay. As regards the non-scheduled banks, Madras had the largest number, followed by a distant second and third by West Bengal and Bombay, respectively (Table 3.11).

Bank Failures and Liquidation/Consolidation of Smaller Banks

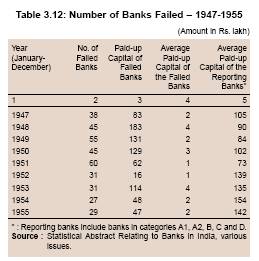

3.43 The partition of the country hurt the domestic economy, and the banking sector was no different. Of the 84 banks operating in the country in the organised sector before partition, two banks were left in Pakistan. Many of the remaining banks in two States of Punjab and West Bengal were deeply affected. In 1947, 38 banks failed, of which, 17 were in West Bengal alone, having total paid-up capital of Rs.18 lakh. The paid-up capital of banks that failed during 1947 amounted to a little more than 2 per cent of the paid-up capital of the reporting banks.15 The average capital of the failed banks between 1947 and 1955 was significantly lower than the average size of paid-up capital of reporting banks in the industry, suggesting that normally it was small banks that failed (Table 3.12).

3.44 The year 1948 was one of the worst years for the relatively larger banks as 45 institutions (out of more than 637 banks) with paid-up capital averaging about Rs.4 lakh were closed down. They failed as they had over-reached themselves by opening more branches than they could sustain on the strength of their resources and by making large loans against property or inadequate security. Some of these, however, had prudential issues as they were functioning with very low capital base. Repeated bank failures caused great hardships to the savers. Failures also reduced faith in the banking system. Most of the savings during this period were in the for m of land and gold. Household savings constituted 66 per cent of the total domestic savings. Of the total household savings, 89 per cent were in physical assets.16 Financial savings flowed in greater measure to the postal department that was considered a safer avenue due to government ownership. Bank deposits mobilised by commercial banks were largely lent out to security based borrowers in trade and industry.

3.45 The first task before the Reserve Bank after independence, thus, was to develop a sound structure along contemporary lines. It was recognised that banks and banking soundness were crucial in promoting economic prosperity and stability. Banks, through their spread and mobilisation of deposits, promote the banking habits and savings in the economy. This could help in garnering resources for investment and development. The initiation of planned economic development required the banking industry to spread far and wide to augment deposit mobilisation and provide banking services.

3.46 The issue of bank failure in some measure was addressed by the Banking Companies Act, 1949 (later renamed as the Banking Regulation Act), but to a limited extent. The Banking Companies Act of 1949 conferred on the Reserve Bank the extensive powers for banking supervision as the central banking authority of the country.17 It focused on basic prudential features for protecting the interests of depositors and covered various aspects such as organisation, management, audit and liquidation of the banking companies. It granted the Reserve Bank control over opening of new banks and branch offices, powers to inspect books of accounts of the banking companies and preventing voluntary winding up of licensed banking companies. The Act was the first regulatory step by the Government of independent India, enacted with a view to streamlining the functioning and activities of commercial banks in India. The Act was long overdue as the Indian Central Banking Enquiry Committee had, in 1931, recommended the enactment of such an Act for India. The most effective of the supervisory powers conferred on the Reserve Bank was the power to inspect banking companies at any time. The Reserve Bank was empowered to inspect any banking company with the objective of satisfying itself regarding the eligibility for a licence, opening of branches, amalgamation, compliance with the directives issued by the Reserve Bank. A key feature contained in this Act was to describe ‘banking’ as distinct from other commercial operations. This was in line with the traditional role of commercial banks, where banks were considered as a special entity in the financial system, requiring greater attention and separate treatment (Selgin, 1996).

3.47 The Banking Companies Act, however, had some limitations. It did not have adequate provisions against abuse of the powers by persons, who controlled the commercial banks’ managements. The Reserve Bank in July 1949 decided to organise efficient machinery for the systematic and periodical inspection of all banking companies in the country, irrespective of their size and standing. The ultimate aim was to create an organisation for the annual inspection of every bank. It was made clear that the primary objective of the inspections was to assist the banks in the establishment of sound banking traditions by drawing their attention to defects or unsatisfactory features in their working methods before they assumed serious proportions necessitating drastic action. The task of evolving an efficient machinery and organisation for conducting the inspections of all the banks was a formidable one.

3.48 Bank failures continued in the period after independence and after the enactment of the Banking Companies Act, although such failures reduced considerably. In order to protect public savings, it was felt that it would be better to wind up insolvent banks or amalgamate them with stronger banks. Accordingly, in the 1950s, efforts were tuned towards putting in place an enabling legislation for consolidation, compulsory amalgamation and liquidation of banks. This was required as the then existing procedure for liquidation was long and time consuming. It involved proceedings in the High Court and caused significant cost and hardship to the depositors. Similarly, the suspension of business was also a long drawn process for licensed banking companies as it involved declaration of moratorium, appointment of official liquidator by the High Court and inspection of the books and accounts of the respective banking companies by the Reserve Bank. Voluntary winding up was an easy exit route for banking companies that were not granted a licence under Section 22, as the provisions of Section 44 did not apply to such banking companies and the prior permission of the Reserve Bank was not required before voluntary liquidation of such companies. This made it easy for the fly-by-night operators to voluntarily wind-up their operations. Many non-scheduled banks, especially in West Bengal became untraceable. Of the 165 non-scheduled banks reported to exist in June 1954, the whereabouts of 107 banks were not known.18 The licence of all of these and the remaining non-scheduled banks, barring six, was cancelled.

3.49 The Travancore – Cochin region also had a large number of small banks. According to a survey by Travancore – Cochin Inquiry Committee in 1954, out of 163 banks in the region, as many as 136 were small set up in hamlets. Of these, only 16 had deposits above Rs.40 lakh. The working capital of 95 banks was less than Rs.10 lakh. Thirty-nine banks had capital and reserves below the level applicable to them under Section 11 of the Banking Companies Act 1949. The Committee suggested that these banks be given time to enhance their capital. Eighteen banks were refused licences. Elsewhere in India, the banks faced fewer problems. At the all-India level, in December 1957, only 21 banks were refused licences as they were beyond repair.

3.50 Even some bigger banks such as the Palai Central Bank were not performing well. Their performance was marred by the poor level of reserves and high percentage of unsecured advances. The Reserve Bank’s Committee of the Central Board in October 1952 considered the possibility of the bank being excluded from the second schedule of the Reserve Bank Act on the basis of the irregularities as pointed out by the inspection report.19 The Reserve Bank had two options, viz., to exercise its powers to close the bank or to nurse it back to normalcy. The first option was easy but was fraught with risks that it might precipitate a systemic crisis. The second option was more difficult. With the interest of depositors in mind, the Palai Bank was given time to improve its working and it was placed under moratorium. However, the bank failed in 1960. There was a public and parliamentary outcry after this failure that speeded up the move towards the requisite legislation to tackle bank failures.

3.51 In the wake of this development, amalgamation of banks was seen as a solution. The moratorium and consequent amalgamation of the Kerala banks ushered in a new era of rapid consolidation of the Indian banking system. Accordingly, the Banking Companies (Amendment) Act 1961 was enacted that sought, inter alia, to clarify and supplement the provisions under Section 45 of the Banking Companies Act, which related to compulsory reconstruction or amalgamation of banks. The Act enabled compulsory amalgamation of a banking company with the State Bank of India or its subsidiaries. Until that time, such amalgamation was possible with only another banking company. The legislation also enabled amalgamation of more than two banking companies by a single scheme. Detailed provisions relating to conditions of service of employees of banks, subject to reconstruction or amalgamation, were also laid down.

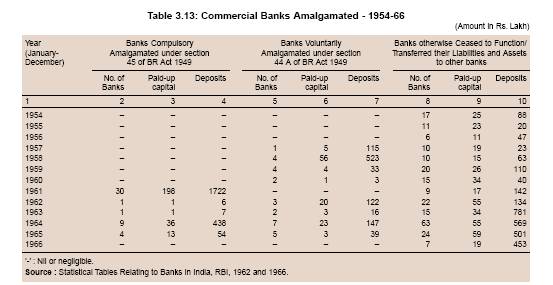

3.52 Between 1954 and 1966, several banks were either amalgamated or they otherwise ceased to function or their liabilities and assets transferred to other banks. During the six year period before the Reserve Bank was formally given the powers in 1960 to amalgamate banks, a total number of 83 banks were amalgamated. However, between the period from 1960 to 1966, as many as 217 banks were amalgamated under different provisions such as under Section 45 of the BR Act 1949 (compulsory amalgamation) and Section 44 A of BR Act 1949 (voluntary amalgamation). Liabilities and assets of those banks which otherwise ceased to function were transferred to other banks. In the year 1960 alone, as many as 30 banks were amalgamated. However, as a conscious policy, the smaller but well-functioning banks were not consolidated. The transferring the assets and liabilities to other banks proved to be a popular exit route. In 1964 alone, as many as 63 banks went out of business (Table 3.13). The process of bank consolidation was accompanied by a vigorous bank licensing policy, wherein the Reserve Bank tried to amalgamate the unviable units. A number of banks that did not comply with the requisite norms were also delicensed.

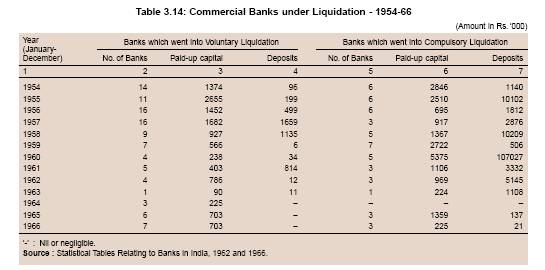

3.53 The process of strengthening of the banking sector also took the form of weeding out the unviablebanks by liquidation or the taking of the assets of the non-functioning banks by other banks. During the period 1954 to 1959 as many as 106 banks were liquidated. Of these, 73 banks went into voluntary liquidation and 33 went into compulsory liquidation. Between 1960 to 1966, another 48 banks went into liquidation (Table 3.14).

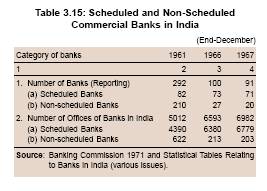

3.54 The policy of strengthening of the banking sector through a policy of compulsory amalgamation and mergers helped in consolidating the banking sector. The success of this could be gauged from the visible reduction in the number of non-scheduled banks from 474 in 1951 to 210 in 1961 and further to 20 in 1967. Their branch offices declined from 1504 in 1951 to 622 in 1961 and to 203 in 1967 (Table 3.15).

3.55 The bank failures and the hardship caused to the depositors led the Reserve Bank to provide safety nets to depositors. The Banking Companies (Second Amendment) Act, 1960, which came into force in September 19, 1960 sought to facilitate expeditious payments to the depositors of banks in liquidation and also vested the Government and the Reserve Bank with additional powers to rehabilitate banks in difficulties. Prior to the Amendment, the procedure for determination of claims of secured creditors and other persons entitled to preferential treatment was mainly responsible for a good deal of delay in the payment to depositors of banks in liquidation. The new provision required that such preferential payment should be made or provided for within three months from the date of the winding-up order or within three months from the date of commencement of the Amendment Act in respect of banks which had gone into liquidation earlier. It further provided that after the preferential payments, the three-month period as specified in the Act, every saving bank depositor should be paid the balance at his credit, subject to a maximum of Rs.250.

3.56 In order to ensure the safety of deposits of small depositors in banks in India, the Deposit Insurance Corporation Act, 1961 was enacted. Accordingly, Deposit Insurance Corporation of India was established in January 1962. India was then one of the few countries to introduce such a deposit insurance; the US was the first country to introduce the deposit insurance. This scheme was expected to increase depositors’ confidence in the banking system and was expected to facilitate the mobilisation of deposits and help promote the spread and growth of the banking sector. The Corporation provided insurance cover against loss of all or part of deposits with an insured bank up to a certain level.

3.57 As a regulator of the banking system, the Reserve Bank was empowered by the Banking Companies Act to inspect banks. The instances of failures of banks in Kerala that occurred due to misappropriation of depositors’ funds by directors underscored the need to strengthen the mechanism of inspection. Accordingly, changes in the policy regarding inspection were made to undertake surprise inspection of banks, and cover many more branches than in the past to detect frauds. The legislative changes that followed took shape in the insertion of a new Chapter IIIA in the RBI Act in 1962. The entire purpose of regulation of banking was to plug the loopholes in law that permitted any irregularity. An amendment Act passed in 1963, which became effective February 1, 1964, gave further powers to the Reserve Bank, particularly to restrain the control exercised by particular groups of persons over the affairs of banks and to restrict loans and advances as well as guarantees given by banks. It also enlarged the Reserve Bank’s powers of control in the appointment and removal of banks’ executive personnel.

Lending to Agriculture and Spread of Banking to Rural Areas

3.58 With independence, not only did the operating environment change but policies also were geared towards planned objectives. Regulation was also aligned to the attainment of these objectives. The adoption of the Constitution in 1950 and the enactment of the State Reorganisation Act in 1956 brought banking in the entire country under the purview of the Reserve Bank. These also enhanced the ambit of the Reserve Bank as a banker to the Government. The Reserve Bank was expected to fill the resource gap for planned purposes. The First Five Year Plan observed that central banking in a planned economy could hardly be confined to the regulation of the overall supply of credit or to a somewhat negative regulation of the flow of bank credit. It would have to take on a direct and active role (i) in creating or helping to create the machinery needed for financing developmental activities all over the country; and (ii) ensuring that the finance available flows in the directions intended.

3.59 The Government’s desire to use banking as an important agent of change was at the heart of most policies that were formulated after independence. These were the first attempts at enhancing the outreach of institutional credit. In India, thus, there was very little support for ‘passive’ or ‘pure’ role of banking. Banks were considered unique among financial institutions and were assigned a developmental role from the beginning of the planned era. Resources amassed from deposit mobilisation were required to be channeled to the most productive uses and the banking system was expected to function as an efficient conduit of the payment system. In doing this, the banking sector was expected to spread the institutional credit across the country. The need for these changes stemmed from the fact that at the time of independence of the country, the banking sector in India was relatively small, weak and concentrated in the urban areas. Most banks in the organised sector engaged primarily in extending loans to traders dealing with agricultural produce.

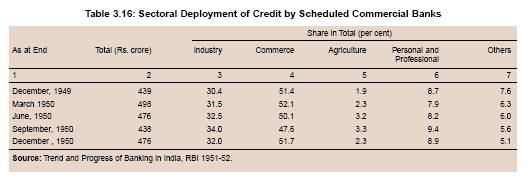

3.60 Banking had not penetrated into the rural and semi-urban centres and usury was still having a field day. A great degree of inter-linkage of markets of agricultural output and credit existed with the agricultural moneylender and traders giving advances to the cultivator and purchasing his produce at less than the market price. Such an inter-linkage between the credit and the output markets had sustained high interest rates and low product price cycles that brought about a high-interest rate-high debt-low income kind of equilibrium. This was sustained as institutional bank credit was not available to agriculture, small industries, professionals and self-employed entrepreneurs, artisans and small traders. Researchers found that since the rural credit markets were isolated, the moneylenders/landlords could act as monopolists and charge exorbitantly high rates of interest to cultivators (Bhaduri, 1977). The inter-linkage of markets of output, credit and labour could be effectively broken only by the spread of the institutional credit. Co-operatives had penetrated into the rural sector but were weak. At the time of independence, most of the bank credit went to commerce and industry, and very little to agriculture (Table 3.16). This was despite the fact that agriculture constituted about 55 per cent of GDP in 1950.

3.61 Lack of knowledge of the area caused asymmetry of information and the grant of small agricultural loans required the banks to maintain a large number of small accounts that were both time-consuming and less profitable. Besides, lending operations were largely security based and the small borrowers had very little security apart from their land, which was often not unencumbered. According to the All India Rural Credit Survey Committee, the total borrowing of the farmers was estimated at Rs.750 crore in 1951-52. Of this, commercial banks provided only 0.9 per cent, agriculturist moneylenders provided 24.9 per cent and professional money lenders another 44.8 per cent. Thus, the financial system at the time of independence was typically underdeveloped. In 1951, there were 551 commercial banks in the country. The bank office to population ratio was at a staggering one branch per 1,36,000 persons.20 Saving habits had also not developed adequately, with the saving rate being at 10 per cent of national income. The underdeveloped banking system was characteristic of a more general lack of depth in the financial system. The needs of the agricultural sector were not met adequately as the banks had no expertise or desire to expand their rural operations. Moreover, banks were run by business houses with other considerations such as profit and financing parent industries. The agricultural operation did not interest many of them.

3.62 Extending the banking facilities to the rural areas was a prominent objective at the time of independence. It was suggested that the Imperial Bank of India should extend its branches to taluka or tehsil towns where the volume of government transactions and business potentialities warranted such extension.21 The Imperial Bank of India was given a target of opening 114 offices within a period of 5 years commencing from July 1, 1951. Other commercial banks and co-operative banks were advised to endeavour to extend their branches to the taluka towns, smaller towns and semi-urban areas. For the villages, it was considered desirable that the machinery of the postal savings banks and cooperative banks should be expanded and more fully utilised. As against the intention to open 114 branches in 5 years, the Imperial Bank of India could open only 63 branches till June 20, 1955.

3.63 The Reserve Bank assumed a unique role in this context that was occasioned by the predominantly agricultural base of the Indian economy and the urgent need to expand and co-ordinate the institutional credit structure for agriculture and rural development. The policy initiative by the Reserve Bank/Government was three-fold. First, to understand the dimension of the problem, a committee was set up. Second, the Imperial Bank of India was nationalised. Third, to address the issue of training of the bank officials in the area of agricultural banking, an institution was set up.

3.64 In order to understand the grass root level situation to be able to address the concerns regarding the financing of the rural sector, the Reserve Bank commissioned the All India Rural Credit Survey Committee (AIRCS) in 1951. The AIRCS survey results were submitted in August 1954 and published in December the same year. The survey had very clear suggestions regarding the Reserve Bank’s development role. The agenda for action and institution-building proposed by the All-India Rural Credit Survey Committee was, by almost any reckoning, impressive in scope and ambition.22 Equally more impressive were its principal recommendations. In fact, many of the changes that took place on the banking scene in India had their genesis in the recommendations of this report. The basic idea that the survey upheld was that banking should help to alleviate problems faced by the average Indian. The Survey Committee observed that the main deficiency of the rural credit system was its lack of focus. The Committee of Direction that conducted this survey observed that agricultural credit fell short of the right quantity, was not of the right type, did not serve the right purpose and often failed to go to the right people. The Committee also observed that the performance of co-operatives in the sphere of agricultural credit was deficient in more than one way, but at the same time, co-operatives had a vital role in channeling credit to the farmers and, thus, summed up that “co-operation has failed, but co-operation must succeed” (Mohan, 2004a). The Committee visualised co-operative credit to be very suitable to address the financial needs of agricultural operations, especially for specialised areas such as marketing, processing and warehousing. It noted that the Imperial Bank of India’s vigorous involvement in promoting the institutionalisation of credit to agriculture could be crucial and recommended the statutory amalgamation of the Imperial Bank of India and major state associated banks to form the State Bank of India (SBI). The Report indicated that the nationalization would be able to initiate an expeditious programme of bank expansion, particularly in rural areas.23 The creation of SBI was expected to ensure that the banking sector moved in consonance with national policies. It was also expected to foster the growth of the co-operative network. According to the Survey, a major obstacle to the establishment of co-operative banks in rural areas was the absence of facilities for the cheap and efficient remittance of cash. Only the Imperial Bank (through the currency chests it got from the Reserve Bank) could offer such facilities.

3.65 The Government, therefore, first implemented the exercise of nationalisation of the Imperial Bank of India with the objective of “extension of banking facilities on a large scale, more particularly in the rural and semi-urban areas, and for diverse other public purposes”. The Imperial Bank of India was converted into the State Bank of India in 1955 with the enactment of the State Bank of India Act, 1955. The nationalisation of the State Bank was expected to bring about momentous changes in the focus from ‘credit worthiness’ to ‘purpose worthiness’. The idea was to gear the banks into institutions that work as efficient conduits in the process of rapid socioeconomic development. A great care was taken to maintain an arm's length relationship between the SBI and the Government. It was in this context that the ownership of SBI was vested with the Reserve Bank. It was felt that the Reserve Bank would be able to safeguard the new institution from political and administrative pressures and ensure its adherence to sound banking principles and high standards of business even while orienting its policy broadly towards the desired ends. It was also believed that this step would preserve the corporate character of the Imperial Bank though under the changed name24.

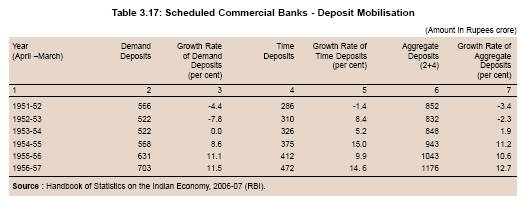

3.66 The State Bank of India, which was required to open 400 branches within 5 years in unbanked centres, exceeded the target by opening 416 branches (Mathur, 1995). The SBI was envisaged to act as the principal agent of the Reserve Bank to handle banking transactions of the Union and the State Governments throughout the country. The step was, in fact, in furtherance of the objectives of supporting a powerful rural credit cooperative movement in India. Its establishment led to a great deal of change in the banking scenario. With the setting up of the State Bank of India, a large number of branches were opened in unbanked centres. The ‘Government’ ownership of the State Bank of India helped it to compete with ‘safe’ avenues like post offices and physical savings. The sustained efforts to expand branch network had a positive impact on deposit mobilisation by banks and the overall savings rate. Aggregate deposits of scheduled commercial banks, which registered a negative growth in 1951-1953 and a small positive growth of 1.9 per cent in 1953-54, grew by 10-12 per cent during the period 1954-55 and 1956-57 (Table 3.17). The increased deposit mobilisation was also facilitated by the increased income levels. The Five Year Plan had a high multiplier effect on the economy. The income levels rose rapidly, which led to the spread of banking habits.

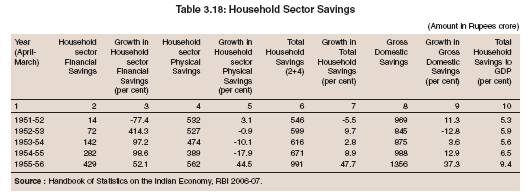

3.67 The increased deposit mobilisation by banks had a favourable impact on financial savings, which grew sharply during 1954-55 to 1955-56. A part of the increased financial savings during 1953-54 and 1955-56 emanated from conversion of physical savings into financial savings (Table 3.18).

3.68 Eight banks that then formed subsidiaries of SBI were nationalised in 1960. This brought one-third of the banking segment under the direct control of the Government. The idea was to spread institutional credit far and wide in order to free the average Indian from the often exorbitant interest rate-debt cycle.

3.69 Another recommendation of the Committee related to the restructuring of the short-term cooperative credit structure and the reorganisation of the institutions specialising in longer-term lending for agricultural development. The Report drew attention towards the need to have adequate institutional credit for medium-term lending to agriculture. These efforts culminated in the creation of Agricultural Refinance Corporation of India in 1963, which was to provide funds by way of refinance. To finance such investments, the Agricultural Refinance Corporation (ARC) was set up by the Act of July 1, 1963. Its objective was to refinance central land mortgage banks, State cooperative banks and scheduled commercial banks.

3.70 In order to address the genuine shortage of trained and experienced professional managers in the banking sector, the Reserve Bank took over the task of providing training facilities for the personnel involved in agri-rural development, co-operative banking and related areas to tone up effectiveness of their managerial staff. Accordingly, the Bankers’ Training College was set up by the Reserve Bank in 1954 for “the purpose of imparting training to bank personnel and improving the quality of management of banks in India”.25

3.71 The Banking Companies Act (section 23) required the banks to obtain the permission of the Reserve Bank before opening a new place of business. The mandate of spreading the umbrella of institutional credit was addressed by putting in place a ‘New Branch Licensing Policy’ in May 1962. The bank expansion policy put in place some entry level norms to take care of prudential requirements like in many other countries that had put in place extensive legal and regulatory norms for entry of banks. The rationale was to reinforce the bank’s internal governance structure and to ensure market discipline. This policy also addressed the social goal of spread of banking as it laid the stress on starting banks in unbanked areas. The identification of unbanked areas was undertaken by examining the data on population per bank office. The new licensing policy marked a change in focus for extension of the banking facilities throughout the country. Prior to the initiation of new policy, branch licenses were granted primarily on the basis of the financial position of banks. It was felt that by linking the grant of permission to open new offices with the financial position of the applicant bank, the general quality of its management, the adequacy of its capital structure and its future earnings prospects could be addressed. With the issue of viability of the banks, the expansion of smaller banks would be discouraged. That is, the policy discriminated in favour of larger and all-India banks.

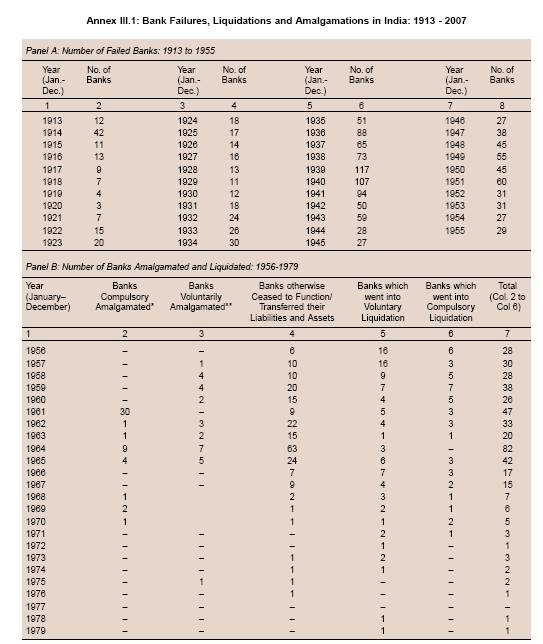

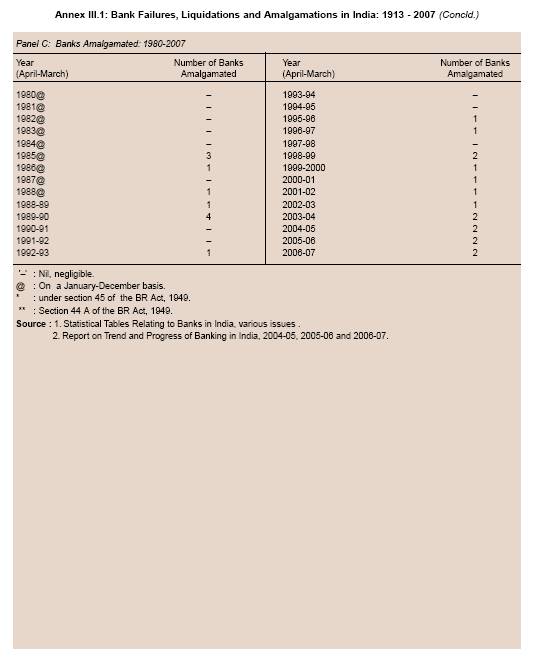

3.72 In every single year between 1913 and 1955, several banks failed in India (Annex III.1). The number of reporting banks increased till 1945, but declined steadily thereafter (Annex III.2).

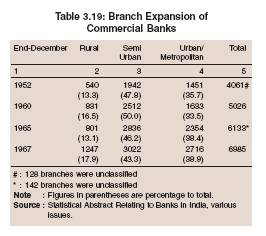

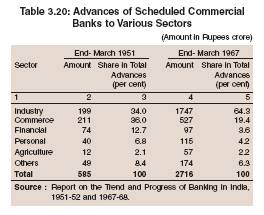

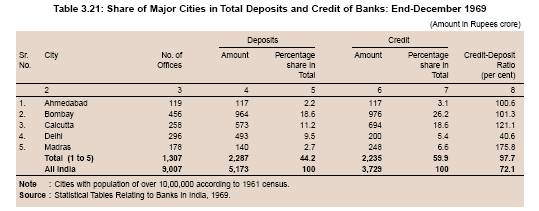

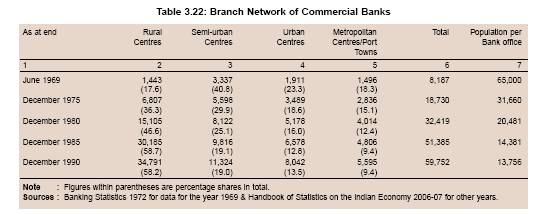

3.73 The number of branches increased significantly between 1952 and 1960 and further between 1960 and 1967. The population per office declined from 1,36,000 in 1951 to 92,000 in 1960 and further to 65,000 in 1967. However, the pattern of branches in rural/semi-urban and urban/metropolitan centres remained broadly unchanged (Table 3.19). The share of agriculture in credit dispensed by scheduled commercial banks also did not improve. Credit to agriculture constituted only 2.2 per cent, i.e., an increase of merely 0.1 per cent between 1951 and 1967 in sharp contrast to almost doubling of the share of industry from 34 per cent in 1951 to 64.3 per cent in 1967 (Table 3.20).

Emergence of Administered Structure of Interest Rates and Micro Controls

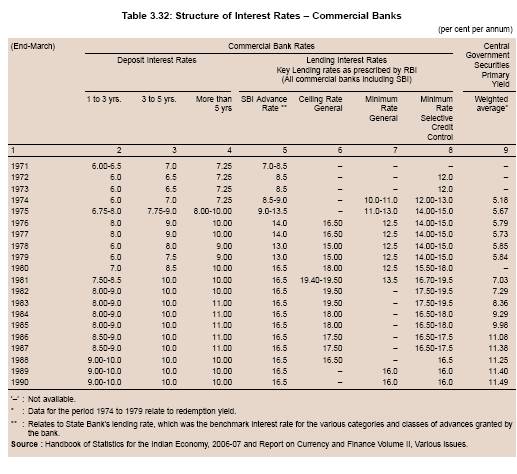

3.74 This period was also difficult for monetary policy as it had to accommodate fiscal policy that was under pressure on account of two wars and a drought. The rising deficit and the accompanying inflation led to an administered structure of interest rates and several other micro controls. In early years, the Reserve Bank relied on direct control over the lending rates of banks, rather than indirect instruments such as the Bank Rate for influencing the cost of bank credit. This was generally done by stipulating minimum rates of interest. The exigencies also required further sub-classification of interest rates with minimum lending rates being separately prescribed for credit against various commodities covered under selective credit control. Also, concessional or ceiling rates of interest were made applicable to advances for certain purposes or to certain sectors to reduce the interest burden, thereby facilitating their development. Interest rates on deposits were also regulated in September 1964. The objectives behind fixing the rates on deposits were to avoid unhealthy competition amongst the banks for deposits and keep the level of deposit rates in alignment with the lending rates of banks to ensure the profitability of banks. Prior to these, changes in interest rates were governed by voluntary inter-bank agreements amongst the important Indian and foreign banks which used to fix ceilings on interest rates. Thus, interest rate regulations were aimed at satisfying the conflicting objectives such as enhancing savings rate, while keeping the cost of credit for productive activities at a reasonably low level. These seemingly opposing objectives were addressed by setting the interest rates according to depositor, borrower, purpose, the background of the borrower, his economic status, type of activity for which the credit was granted and the amount of such credit. Some change in the pattern of deposits was also sought to be achieved by change in the interest rate across the deposit categories. To encourage long-term deposits, the ceilings on deposit rates as well as specification of floors for longer term deposits were prescribed. The need for resources for planned development gradually increased the Government borrowing. The overriding objective of keeping the cost of Government borrowing low, in addition to objectives of promoting growth, and the difficulty in reducing interest rates on bank deposits once they were raised, brought in considerable inflexibility in interest rate determination. While in some measure, all the avowed objectives were addressed, the interest rates ceased to function as a signal of monetary policy. The banks usually compete with each other by setting competitive interest rates. However, under the administrative set-up, the spreads of the banks were well worked out and the banks lost all initiative to optimise their resources, offer competitive rates and retain business. The net result was that borrowers had to pay higher interest rates. Because of the administered structure of interest rates, banks also could not price their products depending on the creditworthiness of the borrowers which also led to misallocation of resources.

3.75 The period during 1961 to 1967 was particularly difficult for the nation. These years witnessed two wars and a series of poor harvest seasons. Given the unstable situation and increased requirement of the public expenditure to be financed against the backdrop of a stagnating agriculture, the Government left no effort spared to ensure that the resources of the banking sector did not go into speculative or unproductive channels. Inflation was high and at times shortages also developed.

3.76 In 1966, the banking sector was increasingly subjected to selective credit controls. The issue of concentration of resources in the hands of a few entities starved the genuinely productive sectors. It was, therefore, decided to take measures to promote effective use of credit and prevent the larger borrowers from pre-empting scarce credit and enlarging the spectrum of borrowers covered by bank credit in the overall context of national priorities as enunciated over the years. Under the Credit Authorisation Scheme(CAS) introduced in 1965, the commercial banks were required to obtain prior permission of the Reserve Bank for sanctioning any fresh working capital limits above the prescribed norm which was revised from time to time. It was first set at Rs. one crore or more to any single party or any limit that would take the total limits enjoyed by such a party from the entire banking system to Rs. one crore or more, on a secured and/or unsecured basis. While in the first few years, the CAS meant no more than a scrutiny of proposed credit facilities with a view to ensuring that large borrowers were not unduly favoured by banks, in the subsequent years, it was seen as a means to achieving a closer alignment between the requirements of the Five Year Plans and the banks’ lending activities.