While the capital to risk weighted assets ratio (CRAR) of the scheduled commercial banks at 12.8 per cent as of

September 2014 is satisfactory, going forward, the banking sector, particularly the public sector banks (PSBs)

would require substantial capital to meet regulatory requirements with respect to additional capital buffers.

With the increased regulatory focus on segregating the cases of wilful defaults and ensuring the equity

participation of promoter(s) in the losses leading to defaults, there is a need for greater transparency in the

process of carrying out a net economic value impact assessment of large Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR)

cases. Another aspect that impinges upon the banks’ asset quality is corporate leverage and its impact on banks’

balance sheets, particularly ‘double leveraging’ through holding company structures and the pledging of shares

by promoters.

Indian stock markets have seen a rapid growth in recent months. While the retail investor base still remains

comparatively low, India’s stock markets have been attracting substantial amounts of foreign investments,

increasing the risks of reversal. The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has introduced an additional

safety net in the form of core settlement guarantee fund to mitigate risks from possible default in settlement of

trades and to strengthen risk management framework in the domestic capital markets.

With a view to improving participation of actual users / hedgers and the quality of price discovery in the market,

the Forward Markets Commission (FMC) has revised position limits which are linked to estimated production

and imports of the underlying commodities.

To deal with issues relating to unauthorised deposit acceptance and financial frauds, the State Level Coordination

Committee (SLCC) mechanism has been strengthened under the initiative of the Financial Stability and

Development Council (FSDC).

Progress on the global regulatory reforms programme

3.1 The financial sector reform programme,

initiated under the aegis of G20 as a response to the

global financial crisis was primarily aimed at correcting

the weaknesses in financial regulation and supervision

mainly in some advanced jurisdictions that caused or

aggravated the global crisis. A broad agreement has

been arrived at with regard to the contours and design

of most of the proposed regulatory reform measures

(for example, banking capital and liquidity regulations,

‘too-big-to-fail’, shadow banking and OTC derivatives,

among others) and the implementation of these

measures is being taken forward based on clear

principles and timelines.1 The implementation is

being coordinated by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) with active involvement of national regulatory,

supervisory and policymaking authorities and

international standard-setting bodies seeking to make

the global financial system safer, more resilient to

shocks and more efficient in catering to the needs of

the real sector for promoting strong and sustainable

economic growth.

Basel III: Banking capital and liquidity standards

Improvement in capital ratios of international

banks

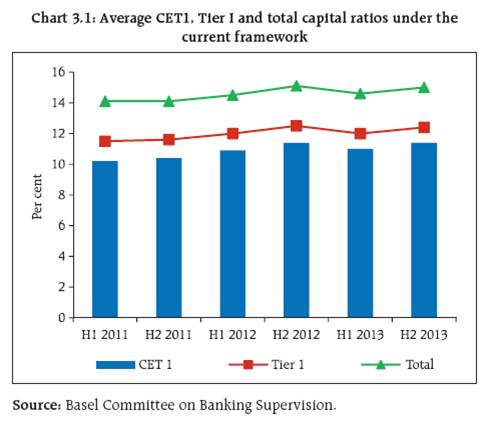

3.2 Regulatory initiatives on banking capital and

liquidity have contributed to the strengthening of

the global banking system. The capital ratios of large

internationally active banks have shown improvement over the last three years.2 The average common equity

Tier I (CET1) capital ratio of these banks rose from

10.2 per cent to about 11.4 per cent of their risk-weighted

assets (RWAs) during the second half of

2013 under the currently applicable regulatory

framework (Chart 3.1). If all the provisions of the

Basel III framework were to be applied on the

December 2013 position, the average CET1 capital

ratio of these banks would fall from 11.4 per cent to

10.2 per cent due to the new definition of eligible

capital under Basel III, deductions that were not

previously applied at the common equity level of

Tier I capital in most countries and increases in RWAs.

The transition, however, is specifically provided for

by Basel III to moderate the immediate impact on

balance sheets.

3.3 As banks adapt themselves to new regulatory

and business realities, the impact on profitability may

raise concerns about their ability to build capital

buffers and meet credit demand. These banks may

require a fundamental overhaul of their business

models, including a combination of re-pricing in

existing business lines, reallocation of capital across

activities or retrenching altogether.

Augmentation of capital: The ‘efficiency-redundancy’

paradigm

3.4 Although the Basel Committee’s global

regulatory standards on bank capital adequacy will

strengthen capital ratios in the long run, they may

also lead to increase in the cost of capital, which in

turn will affect the cost of lending and economic

growth and may force banks into aggressive and

riskier innovations to maintain their return on equity

(RoE). The issue has also created debates over the efficiency-redundancy trade-off involved in extra

capital that banks are mandated to raise. Furthermore,

an improvement in capital ratios per se may not

necessarily lead to improvements in the capacity of

banking institutions and their contribution to

economic development as capital ratios may increase

on account of many factors.

3.5 Previous Financial Stability Reports (FSRs)

have discussed issues relating to the possibility of

manoeuvring of risk-weights, especially under

internal models-based approaches for different types

of risks under the Basel framework. In order to

strengthen the comparability of implementation

across jurisdictions, the Basel Committee has started

an analysis of the discretions in risk-weight

prescriptions to understand how much they contribute

to unwarranted variations in capital standards. This

has been highlighted by some recent studies3 on the

variation of risk-weighted assets in the banking book

and the trading book. Going forward, some of these discretions may be removed in 2015.4 Further, Basel

Committee is examining prescription of other policy

measures and benchmarks to ensure more consistency

as part of Regulatory Consistency Assessment Process.

3.6 The introduction of a minimum Tier I

leverage ratio of 3 per cent by Basel Committee on

Banking Supervision (BCBS), was aimed at constraining

the build-up of leverage in the banking sector and

reinforcing risk-based capital requirement measures

with a simple and non-risk based ‘backstop’ measure.

The Reserve Bank has prescribed that banks should

strive to achieve a minimum Tier 1 leverage ratio of

4.5 per cent during the parallel run period.

Proposals for tougher capital measures for

addressing ‘too-big-to-fail’

3.7 Policy proposals on the adequacy of loss-absorbing

and recapitalisation capacity of Global

Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs)5 has been

under consideration in the form of a common

minimum requirement for their ‘gone-concern loss-absorbing

capacity’ (GLAC). In the recently released

set of principles6 for public consultation on the loss-absorbing

capacity of G-SIBs in resolution, FSB has

proposed a single specific minimum Pillar 1 ‘total

loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC)’ requirement to be set

within the range of 16–20 per cent of RWAs under the

condition that the minimum level should be at least

twice the Basel III Tier I leverage ratio requirement.

3.8 The objective of the TLAC requirements is to

ensure that G-SIBs have adequate loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity necessary to ensure that in

and immediately following a resolution, critical

functions can be continued without tax payers’ funds

or financial stability being put at risk. Implementation

of TLAC and the final calibration of the common Pillar

1 minimum TLAC requirement will take into account

the results of this consultation and the Quantitative

Impact Study and market survey which will be carried

out in early 2015.

3.9 TLAC requirements are not applicable to any

Indian bank as none of them is a G-SIB. However, it

may not be possible to rule out the risk of spill over

impact on emerging market and developing economies

(EMDEs) due to the adverse impact of the TLAC

proposal on G-SIBs.

Assessment of impact of higher capital requirements

3.10 Some studies7 show that, ceteris paribus, if

the ratio of common equity for a given loan is

increased by 2 per cent, banks will require to raise

the lending rate by 40 basis points (bps) in US and

19 bps in Europe, to maintain a level of 12 per cent

RoE. It has been observed that the banks tend to pass

on the increased cost to the lending spread without

any adjustments to other heads of income. Increased

cost of lending might impact the credit off-take from

banking sector.

3.11 Various studies to assess the impact of

implementation of Basel III on growth point towards

the negative impact of higher capital requirements

on GDP.8 Analytical work also shows that Basel III requirements will have spill over effects in the nonbank

financial sector due to shifting of credit to the

non-bank financial sector. A few other studies on the

assessment of the impact of implementation of Basel

III specifically focus on EMDEs.9

Capital levels of Indian banks

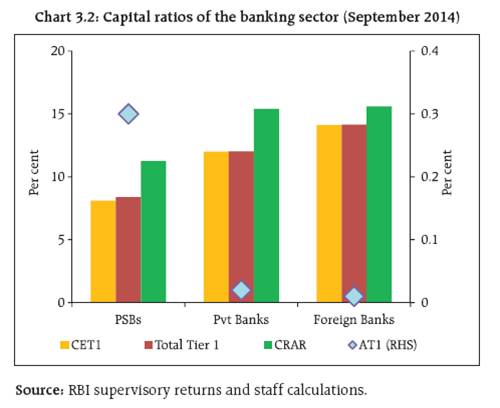

3.12 India has implemented Basel III capital

framework from April 1, 2013. The CRAR for Indian

banks under Basel III as of September 2014 stood at

a satisfactory level of 12.8 per cent (as against 13 per

cent as of March 2014). Banks are expected to remain

under pressure on account of additional requirements

towards the capital conservation buffer, the

countercyclical capital buffer and supervisory capital

under pillar 2 (Chart 3.2). While all bank groups met

the segregated requirements of minimum CET1 and

Tier I capital ratios as at the end of September 2014,

if the additional requirement of 2.5 per cent in the

form of CET1 for meeting the capital conservation

buffer is considered in future, then the capital

requirements, especially of public sector banks

(PSBs), would go up further.

3.13 Apart from the cost implications of raising

additional capital, banks will face challenges in terms

of depth, liquidity and sufficient appetite in India’s

capital markets for such risk bearing Additional

Tier I (AT1) capital instruments. In the absence of a

wider retail market, few select investor categories

and institutional investors, mainly insurance

companies might end up holding much of the AT1

instruments issued by banks (Chart 3.3). Since such

institutional investors mostly hold such securities

till maturity, feedback for pricing of such instruments

through secondary market trades are conspicuously

absent. In the absence of effective market making,

the banks may have to bear higher costs for issue of

such instruments relative to their international peers.

This issue further underlines the need for

development of a robust non-government debt

market.

3.14 On its part, as owner of the dominant part

of the banking industry, the Government of India

has made capital infusion of `586 billion in PSBs in

the last four years (2011-14) and plans to further

infuse an amount of `112 billion in 2014-15. Capital

infusion has broadly been carried out by way of

preferential allotment of equity by the banks. The

government is planning to bridge this gap by diluting

its stake in some PSBs to 52 per cent to enable banks

to raise capital from the market. Tentative calculations

show that PSBs require significant capital injection

in order to sustain even a moderate 15 per cent

compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) in RWAs.

Market valuations of PSBs and implicit sovereign

guarantee

3.15 Capital raising efforts by PSBs other than the

capital infusion by the government, face challenges

because of their relatively low equity valuations

compared to their private sector peers. The previous

FSR had raised issues about the low valuation of PSBs.

Despite implicit backing from the government, the

low equity valuations are justified by the options

pricing model for valuation of equity. The implicit

sovereign guarantee cannot be treated directly in this

model because if the value of a firm falls below the

face value of debt, then compensation to debtors is

assumed to be made up by the sovereign, but no

compensation will be forthcoming to equity investors.

Hence, the fortunes of equity investors are unaffected

by an implicit sovereign guarantee of debt. The

ultimate improvement in valuations can only come

from commensurate improvements in asset quality,

governance structures and operational efficiency.

Liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) norms

3.16 According to the guidelines issued by the

Reserve Bank on the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) in

June 2014, banks were permitted to reckon

government securities to the extent allowed by the

Reserve Bank under its Marginal Standing Facility

(MSF) as Level 1 High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA)

under LCR. Subsequently, banks have been allowed

(with effect from January 1, 2015) to include

government securities held by them up to another 5

per cent of their net demand and time liabilities

(NDTL) within their mandatory Statutory Liquidity

Ratio (SLR) requirement (see Box 3.2 for details). Such

government securities reckoned as HQLAs for the

LCR are to be valued at an amount not greater than

their current market value.11

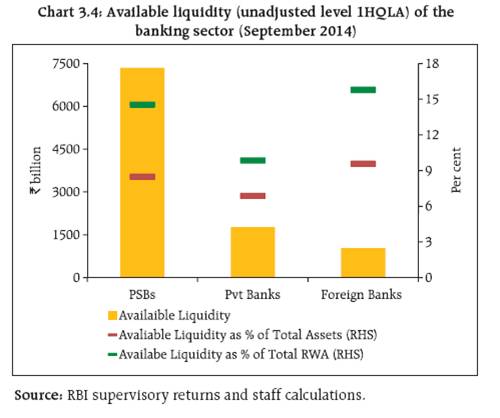

3.17 As of September 2014, the banking sector had

a liquidity buffer, represented by unadjusted level 1

HQLA12, of over `10 trillion which was around 8.2 and

13.5 per cent of total banking sector assets and RWAs

respectively (Chart 3.4). However, since LCR has to be

adopted in each significant currency separately, the

implementation of Basel III LCR norms for the foreign exchange portfolio of Indian banks may have

profound implications for the way the business is

being conducted hitherto. Currently, the foreign

exchange business model for Indian banks involves

running negative gaps (the duration of assets longer

than that of liabilities), with negligible foreign

currency HQLA backing. Moreover, overseas branches

being the major source of foreign exchange liabilities

may themselves be subject to host country liquidity

regulations, including implementation of Basel III

norms on a location by location basis (i.e. gross) and

not aggregate (i.e. net) basis, which may be further

adding to cost. After negative carry in prospective

HQLA in major currencies are taken into account, the

profitability of overseas operations as well as foreign

exchange book of major banks is likely to be materially

affected. The issue requires careful cost benefit

analysis of maintaining overseas operations of Indian

banks as well as an appropriate strategy to deal with

emerging liquidity regulations.

Shadow banking

3.18 The role of the ‘shadow banking system’,

defined as ‘credit intermediation involving entities

and activities outside the regular banking system’, as

a source of systemic risk was an important learning

outcome of the global financial crisis. Its importance

stemmed not only from its direct role in supplying

credit or liquidity to the economy but also due to its

interconnectedness with the more closely regulated

banking system.

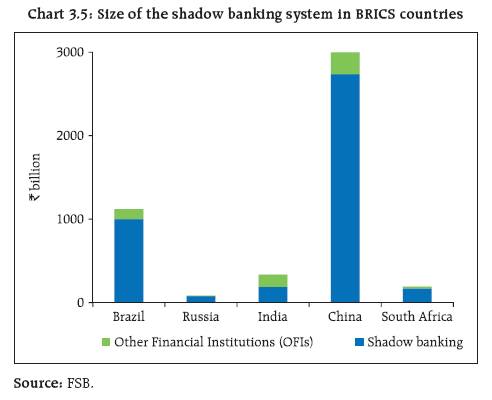

3.19 According to the FSB methodology and

classification, the size of the shadow banking sector

in India is estimated to be around USD 190 billion,

which is the 15th largest in the world. Among the

BRICS, India has the third largest shadow banking

sector (Chart 3.5).

Regulation of non-banking finance companies

3.20 The G20/FSB led reform proposals initiated

in this regard were aimed at developing appropriate

monitoring and regulatory frameworks to mitigate

the potential build-up of risks in and through the shadow banking system. The FSB approach was based

on first capturing the data and information with

respect to all kinds of non-bank credit intermediation

and then concentrating on the areas of non-bank

credit intermediation where maturity/liquidity

transformation and/or flawed credit risk transfer and/

or leverage could potentially create important

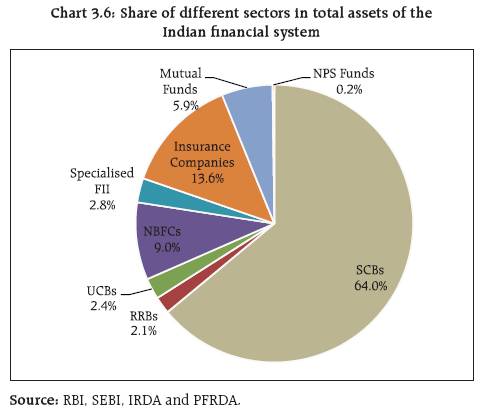

systemic risks. In the Indian financial system what

has been reckoned as shadow banking by the FSB are

predominantly non-banking financial companies

(NBFCs), which have been under prudential

regulation for a long time and account for a relatively

small share of the total assets of the Indian financial

system (Chart 3.6).

3.21 However, given the significant

interconnectedness of NBFCs with the rest of the

financial system, especially banks (Table 3.1) they

could impact banks under conditions of stress and

may face difficulties if banks show reluctance to lend

to them in case of a liquidity crunch.

3.22 Considering these aspects, regulations for

NBFCs have been tightened (Box 3.1). Furthermore,

efforts were also made to assess the size and profile

of actual shadow banking entities. From a preliminary

reconciliation of the database of the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA), Government of India, on

companies registered under the Companies Act, 1956

and classified under ‘Financial Intermediation, except

Insurance and Pension Funding’ and ‘Activities

auxiliary to Financial intermediation’, it is observed

that many of these companies though not registered

with the Reserve Bank might be carrying on (nonbanking)

financial activities. Financial statements of

many such companies reveal that a significant

number of them could be termed as NBFCs as per the

Principal Business Criteria (PBC) specified by the

Reserve Bank. Such companies include a small

number of deposit taking companies and also

companies whose applications for registration were

cancelled by the Reserve Bank on various grounds.

Table 3.1: Exposure of banks, AMCs and insurance

companies to top NBFCs13 |

(` billion) |

Mar

2012 |

Mar

2013 |

Mar

2014 |

Sep

2014 |

Banks |

1513 |

1453 |

2919 |

1495 |

AMCs |

83 |

624 |

756 |

912 |

Insurance Companies |

780 |

880 |

965 |

1023 |

Source: RBI supervisory returns and staff calculations. |

Box 3.1: Salient Features of Revised Regulatory Framework for NBFCs

i) The minimum Net Owned Fund (NOF) criterion for

existing NBFCs (those registered prior to April 1999)

has been increased to `20 million. NBFCs have been

allowed till March 2017 to achieve the required

minimum levels.

ii) In order to harmonise and strengthen deposit

acceptance regulations across all deposit taking

NBFCs (NBFCs-D) credit rating has been made

compulsory for existing unrated asset finance

companies (AFCs) by March 31, 2016. Maximum

limit for acceptance of deposits has been harmonised

across the sector to 1.5 times of NOF.

iii) In view of the overall increase in the growth of the

NBFC sector, the threshold for defining systemic

significance for non-deposit taking NBFCs has been

revised to `5 billion from the existing limit of `1

billion. Non-deposit taking NBFCs shall henceforth

be categorised into two broad categories: NBFCs-ND

(those with assets less than `5 billion) and NBFCs-

ND-SI (those with assets of `5 billion and above –

deemed as systemically important) and regulations

will be applied accordingly. NBFCs-ND will be

exempt from capital adequacy and credit

concentration norms while a leverage ratio of 7 has

been introduced for them.

iv) For NBFCs-ND-SI and all NBFCs-D categories, tighter

prudential norms have been prescribed - minimum Tier I capital requirement raised to 10 per cent (from

earlier 7 per cent in a phased manner by end of

March 2017), asset classification norms (from 180

days to 90 days in a phased manner by the end of

March 2018) in line with that of banks and increase

in provisioning requirement for standard assets to

0.40 per cent in a phased manner by March 2018.

Exemption provided to AFCs from the prescribed

credit concentration norms of 5 per cent has been

withdrawn with immediate effect. Additional

corporate governance standards and disclosure

norms for NBFCs have been issued for NBFCs-D and

NBFCs-ND.

v) NBFCs with assets of less than `5 billion shall not

be subjected to prudential norms if they are not

accessing public funds and those not having

customer interface will not be subjected to conduct

of business regulations.

vi) Assets of multiple NBFCs in a group shall be

aggregated to determine if such consolidation falls

within the asset sizes of the two categories.

Regulations as applicable to the two categories will

be applicable to each of the NBFC-ND within the

group. Reporting regime has been rationalised with

only an annual return prescribed for NBFCs of assets

size less than `5 billion.

3.23 A preliminary exercise to map the universe

of ‘finance’ companies currently not registered with

the Reserve Bank shows that the relative proportion

of the segment of un-registered companies in terms

of asset size may be much lower than companies

under Reserve Bank’s regulation. Thus, a large

number of small companies populating the NBFC

sector do not appear to be posing a major risk to

systemic stability (Table 3.2). Nonetheless, they give

rise to issues with regard to consumer protection as

well as reputational risks for the regulator. In this

regard the State Level Coordination Committee

(SLCC)14 mechanism has been strengthened under

the initiative of the Financial Stability and

Development Council (FSDC) to improve surveillance and deal with issues such as unauthorised deposit

acceptance and financial frauds.

Need to bring government owned NBFCs under

prudential regulations

3.24 In addition to NBFCs in the private sector,

there are some (central and state) government owned

finance companies (not being banks) registered with

the Reserve Bank as NBFCs, which account for

significant proportion of the total assets and business

of the NBFC sector. Government owned NBFCs hold

37 per cent of the assets of the entire NBFC sector

but are exempt, at present, from certain regulatory

prudential norms of the Reserve Bank. These NBFCs

are highly leveraged with a leverage ratio of 6.4

(leverage of state government owned NBFCs at 8.8

and central government owned NBFCs at 6.2) as

compared to 3.3 for the entire sector. Their aggregate

outside liabilities are around `3.8 trillion of which

`385 billion are in the form of bank borrowings.

3.25 While these NBFCs have been playing a useful

role in financing certain critical infrastructure sectors,

and certain degree of forbearance might have been

warranted in the initial stages, there is a need to bring

all deposit taking and systemically important

government owned companies under the prudential

regulatory framework as applicable to other NBFCs,

especially in view of the rationalisation of regulations

(and where necessary, alignment with banking sector

regulations).

Table 3.2: Size-wise distribution of NBFCs registered with the Reserve Bank |

Assets size category (in `) |

Number of companies |

Total Assets size

(in ` billion) |

Proportion of Number of

Companies (%) |

Proportion of

Total Asset Size (%) |

Above 1 billion |

454 |

11621 |

3.8 |

89.6 |

500 Million to 1 billion* |

686 |

490 |

5.7 |

3.8 |

Up to 500 million |

9555 |

854 |

79.4 |

6.6 |

Data not available |

1334 |

NA |

11.1 |

|

* Data pertains to 384 reporting companies |

Indian banking sector’s health and asset quality:

Focus on PSBs

Regulatory forbearance

3.26 The extent of restructured assets in the

banking sector, especially PSBs, is a cause of serious

concern (see Chapter II for details). The relatively

higher possibility of slippages in restructured

standard advances is required to be factored in by

banks from the capital adequacy perspective. Even

in ‘business as usual’ conditions (as against ‘stressed

conditions’), any restructured advance which would

be generally categorised by a rating agency as a sub-investment

grade, carries much higher probability of

turning into non-performing asset (NPA) than a

standard asset. Since banks, traditionally have been

short term working capital providers, their

appreciation of idiosyncratic risks in infrastructure

projects seems to have been inadequate. Hence, the

appraisals of most of the project loans have been the

prerogative of a handful of merchant banks. However,

since the compensation of merchant banks is linked

to closure of funding and the decision to fund the

respective projects still rests with the banks, it is

necessary that the banks strive for a more detailed

understanding of the risk-return profile of the

underlying projects before committing funds,

whenever project appraisal is outsourced.

3.27 While it may be somewhat legitimate to

justify regulatory forbearance in times of major

crises, forbearance for extended periods and as a

cover to compensate for lenders/borrowers’

inadequacies engenders moral hazard. Furthermore,

going forward, with the initiation of risk based

supervision as well as implementation of Basel II

advanced norms for credit, accounting discretions

such as restructuring will have no impact on capital

requirements since such processes incorporate

capital provisioning based on expected losses , (i.e.

internal rating based approach for credit risk under

Basel II or the Risk Based Supervision model initiated

by the Reserve Bank) and would largely align regulatory capital with economic capital rendering

discretionary accounting forbearance of little

consequence. Hence, an early end to regulatory

forbearance may be the right step. In addition,

governance reforms along the lines suggested by the

P.J. Nayak Committee will build in inherent checks

and balances on the risks and returns of the credit

portfolio thereby leading to more informed risk

taking.

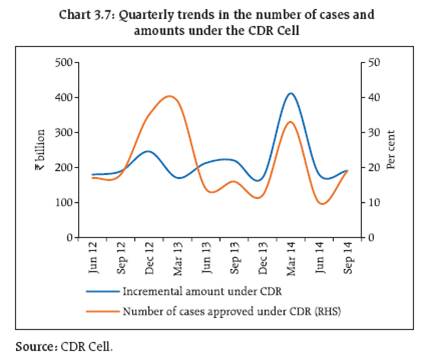

Reduction in cases referred under CDR in the last

six months

3.28 Out of the total number of cases referred to/

approved under CDR, 49 per cent have been

successfully implemented till date. Further, it is

observed that the number of cases referred to the

CDR cell has come down in the recent past

(Chart 3.7). One of the reasons for this reduction

could be the Reserve Bank’s move to allow banks to

restructure their large credits with aggregate exposure

(AE) of `1 billion and above outside CDR under the

Joint Lenders’ Forum (JLF) constituted under the

provisions of the ‘Framework to Revitalise the

Distressed Assets in the Economy’ which became

effective from April 1, 2014. (Box 3.2).

3.29 There is also a need to review and strengthen

the accountability mechanism in the entire process

of reference, approval and implementation or exit

under CDR. Adequate disclosures on the eventual

cost-benefit profile of approved CDR cases (for

successful as well as failed cases) will help in forming

policy and aid proper use of scarce resources. With

increased regulatory focus on segregating cases of

wilful defaults and ensuring adequate equity

participation of promoter(s) in the losses leading to

defaults, there is a need for greater transparency in

carrying out a net economic value impact assessment

and audit of big ticket CDR cases.

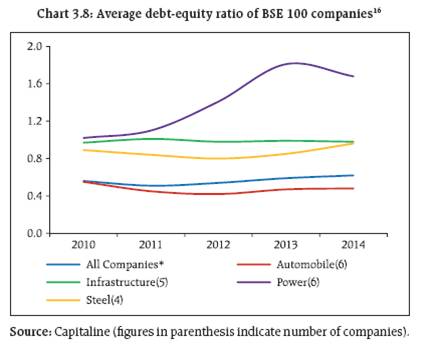

Corporate leverage

3.30 A related issue that impinges on the banks’

asset quality is the understanding of corporate

leverage and assessment of the impact on banks’

balance sheets. A report of the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) has flagged that trends in

corporate leverage ratios in emerging Asia (including

India) represented a ‘fault line’, with the potential

to amplify shocks as global liquidity conditions

tighten, interest rates rise and growth slows.15 In the

Indian context, various reports on indebtedness

among Indian companies (and business groups at the

aggregate level) have pointed towards increasing

corporate leverage (debt-to-equity) ratios, though the

Indian scenario is somewhat different with many

cash rich companies coexisting with debt ridden

companies (Chart 3.8). The euphoria during the

boom period might have driven many Indian

companies towards huge expansion/acquisition

programmes. For many such companies the slowdown

in the post-global financial crisis has been a shock

and there is some evidence that several of them are

on the path of deleveraging and the debt equity ratios

of many corporates seem to be stabilising, if not

tapering.

3.31 With renewed focus on speedy regulatory

clearances for projects and their implementation, the

profitability of corporate entities is expected to

improve once the stalled projects reach the stage of

commercial operations, thus also helping the cause

of the asset quality of the banking system.

Simultaneously, it may be pertinent to examine the

implications of certain corporate practices in India

relating to multi-layered structures and pledging of

shares by promoters which will improve an assessment

of vulnerabilities and the remedies thereof while

helping redefine regulatory and supervisory responses.

Effective leverage under holding company/SPV

structures

3.32 While the holding company structure has

evolved primarily to consolidate a group’s holdings

in various companies/projects, concerns emanate

when such holding companies start acting as

operating entities. The evolution of special purpose

vehicles (SPVs) may also be associated with the need

to reduce bankruptcy costs (and hence risks to

lenders). A practice popularly known as ‘double

leveraging’ has been prevalent, especially in the

infrastructure space since companies that undertake mega projects need not raise a lot of resources while

satisfying their equity contributions. In a typical

double leveraging, a holding company raises debt on

its balance sheet and infuses it as equity in SPVs.

From the lenders’ perspective, a debt-to-equity ratio

of 2:1 at the holding company level could transform

into a leverage of 8:1 at the SPV level. While there

could be some merit in such practices, risk assessments

by banks need to capture this effectively.

Implications of pledging of shares by promoters

3.33 The December 2013 FSR raised certain

concerns over pledging of shares by promoters. This

report examines the issue further from the lenders’

perspective. A majority of Indian companies are

family owned/controlled, as substantial levels of

promoter shareholding are concentrated within the

family hold (Table 3.3). The promoter shares can be

significant collateral for a typical company if it wants

to expand leverage. Pledging of shares is practiced in

other advanced economies too, but it has taken a

significantly different form in India.17 In the case of

a typical Indian company, the promoters pledge

shares not for funding ‘outside’ business ventures

but for the company itself. By pledging shares, the

promoters have no personal liability other than to

the extent of their pledged shares. In some instances

the shares pledged by unscrupulous promoters could

go down in value and the promoters may not mind

losing control of the company as there is a possibility

of diversion of funds before the share prices

collapse.18 While a lender has the option of selling

the shares when prices fall and hit a point that can

be called a default event, this can still have impact

on minority shareholders through market impact

costs, as with the invoking of the pledge, the pledged

shares will have to be sold immediately.

Table: 3.3: Industry-wise position on proportion of promoters’ pledged shares (as of March 2014) |

(in per cent) |

Sector |

Indian

Promoters |

Foreign

Promoters |

Total

Promoters’

Holding |

Promoters'

Ownership

Pledged |

Banks |

49.0 |

0.7 |

49.7 |

0.1 |

Engineering |

35.8 |

0.5 |

36.3 |

11.2 |

Financial Services |

47.4 |

1.1 |

48.4 |

7.6 |

FMCG |

27.9 |

3.2 |

31.1 |

11.7 |

Infrastructure |

69.8 |

1.1 |

70.9 |

14.7 |

Information Technology |

43.0 |

4.9 |

47.9 |

11.2 |

Manufacturing |

50.5 |

7.0 |

57.5 |

18.1 |

Media and Entertainment |

44.3 |

5.2 |

49.4 |

24.9 |

Petrochemicals |

54.8 |

5.3 |

60.1 |

8.7 |

Pharmaceuticals |

47.1 |

6.0 |

53.1 |

5.4 |

Services |

46.3 |

9.7 |

56.1 |

25.5 |

Telecommunication |

51.4 |

5.8 |

57.3 |

12.8 |

Miscellaneous |

53.1 |

2.8 |

55.9 |

12.6 |

Total |

51.6 |

4.7 |

56.3 |

14.2 |

Source: National Stock Exchange. |

3.34 In view of the prevalence of promoters

pledging a substantial portion of their shares, the

resultant leverage could be a concern not only for

shareholders but also for the health of the financial

system. This issue calls for a closer examination,

especially in the current scenario of buoyancy in stock

prices wherein the collateral in the form of pledged

shares may appear to justify higher leverage. In this

regard, the fundamental question is one related to

implications from a company’s perspective of the

practice wherein a company’s own shares can be

pledged to raise debt on its balance sheet.

Move towards a diversified banking system in India

3.35 The final guidelines for setting up ‘Payments

Banks’19 and ‘Small Finance Banks’20 have been issued on November 27, 2014. The primary objective of setting

up these differentiated banks will be to further increase

financial inclusion. The payments banks target at

providing small savings accounts and payments/

remittance services to the migrant labour workforce,

low income households and small businesses by

enabling high volume-low value transactions in deposits

and payments/remittance services in a secured

technology-driven environment. On the other hand, the

small finance banks shall help in provision of savings

vehicles primarily to unserved and underserved sections

of the population and supply of credit to small business

units, small and marginal farmers, micro and small

industries, and other unorganised sector entities,

through ‘high technology-low cost’ operations.

3.36 While a small finance bank will engage in

basic lending activities, a payments bank will be

limited to only accepting deposits up to a maximum

of `100,000 per individual customer. Further, the

small finance banks could also undertake other non-risk

sharing simple financial services such as

distribution of mutual fund units and insurance and

pension products. They can also become category II

authorised dealers in the foreign exchange business

for clients’ requirements. The scope of activities for

payment banks on the other hand will require them

to maintain a minimum 75 per cent of demand

deposit balances in SLR securities with a maturity up

to one year, besides maintaining Cash Reserve Ratio

(CRR) requirements. They will be allowed to deposit

a maximum of 25 per cent in other SCBs for

operational purposes and liquidity management.

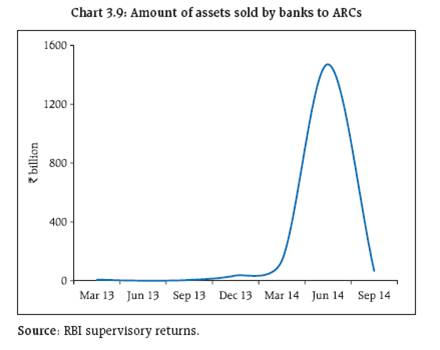

Asset reconstruction companies (ARCs)

3.37 In view of sudden spurt in sale of NPAs by

banks (mainly the PSBs facing asset quality pressures)

to ARCs during recent quarters, the previous FSR had

highlighted certain aspects related to the functioning

of ARCs and the need for a review of the regulatory

framework for the sector. A well capitalised and efficient ARC sector may play an important role in

the coming years in reconstruction and resolution of

stressed assets. There are 14 ARCs currently

functioning in India, out of which two have majority

ownership by public sector institutions, six have

shareholding which is a mix of the public and private

sectors (including foreign institutions), while the

remaining six are fully owned by the private sector.

Indian banks, both public sector and privately owned,

have a significant level of ownership stake in ARCs.

With further opening up of the economy, it is

expected that the ARC sector will attract substantial

fresh foreign investments.21

Impact of changes in regulatory norms

3.38 ARCs have witnessed very high growth in

recent times riding on the business opportunities

arising out of a high level of NPAs in the banking

sector. The fourth quarter of the previous financial

year (2013-14) and the first quarter of 2014-15 saw a

surge in their asset acquisition, with a number of

transactions being closed at aggressive prices. The

quarter ended September 30, 2014 however,

witnessed a sharp decline in acquisition (Chart 3.9).

3.39 The fall in asset acquisition by ARCs during

the last quarter may have been partly due to the

revised regulations introduced by the Reserve Bank

in August 2014. The revision of regulations enhanced

‘skin in the game’ for ARCs by mandating increased

investment in security receipts (SRs) from 5 per cent

to 15 per cent, linking the calculation of management

fee with the net asset value (NAV) of SRs rather than

the outstanding SRs issued as hitherto. The rationale

behind these regulatory changes was to incentivise

realisation and thereby expediting the process of

recoveries/restructuring as NAV of SRs is calculated

on the basis of the likely rate of recovery of stressed

assets. With the regulatory changes effected in August

2014, ARCs will need to focus on actual redeeming

of security receipts as it is no longer possible for them

to base their profit model on the basis of management

fees (details in Box 3.2). In the near term, ARCs may

find it difficult to align their pricing to the expectations

of the selling banks and the selling banks also may not have yet reconciled to a realistic sale price

expectation for the assets that they want to offload,

resulting in the reduction in sales during the second

quarter ended September 2014.

3.40 Some other regulatory measures introduced

in the guidelines for ARCs, inter alia, are greater

disclosures on the part of ARCs, membership in the

Joint Lenders’ Forum (JLF) in order to participate in

a corrective action plan for restructuring stressed

assets, lowering the threshold level to enforce the

Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets

and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act,

providing more time to ARCs to conduct due diligence

on stressed assets on the auction block, a shorter

period for valuation of SRs and a shorter planning

period for reconstruction. It is expected that a greater

degree of transparency in the sector will support its

long term sustainability as an effective institutional

response to controlling NPAs.

Box 3.2: Important Regulatory and Supervisory Measures

Dealing with domestic systemically important banks

(D-SIBs): Based on the internationally agreed reform

measures, the framework for dealing with D-SIBs in

India was issued in July 2014. The assessment

methodology incorporates major indicator categories:

size, interconnectedness, substitutability and

complexity. Based on their systemic importance scores

in ascending order, banks are slotted into four different

buckets and will be required to have additional CET1

capital ranging from 0.20 per cent to 0.80 per cent of

risk-weighted assets depending on the bucket that they

are slotted into. The computation of systemic importance

scores will be carried out at yearly intervals and the

banks classified as D-SIBs will be disclosed in August

every year starting from 2015.

Capital and provisioning requirements for bank

exposures to entities with unhedged foreign currency

exposure: Corporates’ unhedged foreign currency

exposures have been an area of concern not only for

individual corporates but also for the financial system as

a whole. The final guidelines, issued in January 2014, provide a methodology to be adopted by banks to

compute incremental provisioning and capital

requirements. More specifically, the incremental

provisioning requirements are to be calculated as per

the ratio of likely loss due to foreign exchange movement

to a company’s earnings and depreciation and

incremental capital will need to be provided accordingly.

It is expected that these measures will incentivise

corporates to hedge their foreign currency exposure and

also enable banks to develop capabilities to measure

and manage currency-induced risks.

Capital requirements for bank exposures to Central

Counterparties (CCPs): In order to promote central

clearing through well managed CCPs, in January 2014

banks were advised that their clearing exposure to a

Qualifying CCP (QCCP) would be kept outside of the

exposure ceiling of 15 per cent of its capital funds

applicable to a single counterparty. Other exposures to

QCCPs such as loans, credit lines, investments in the

capital of CCP, liquidity facilities, etc. will continue to be within the existing exposure ceiling of 15 per cent of

capital funds to a single counterparty. However, all

exposures of a bank to a non-QCCP should be within

this exposure ceiling of 15 per cent.

Countercyclical capital buffer: Taking into consideration

the evolution of the Indian economy and other relevant

factors including the BCBS document on this aspect, a

countercyclical capital buffer (CCB) was prescribed for

banks that in addition to their private sector lending,

takes into account other relevant factors such as the

incremental C-D ratio for a moving period of three years

(along with its correlation with the credit-to-GDP gap

and GNPA growth), the industry outlook assessment

index (along with its correlation with GNPA growth) and

interest coverage ratio (along with its correlation with

the credit-to-GDP gap). Decisions on CCB may be preannounced

with a lead time of four quarters. The lower

threshold (L) where the CCB is activated was

recommended at 3 percentage points of the credit-to-

GDP gap, provided its relationship with GNPA remains

significant and the upper threshold (H) where the CCB

is at its maximum was stipulated at 15 percentage

points of the credit-to-GDP gap.

Revitalising distressed assets: A framework for

revitalising distressed assets in the economy was

operationalised by the Reserve Bank with effect from

January 2014. In essence, the framework outlines a

corrective action plan that will incentivise an early

identification of problem accounts which are considered

viable and their timely restructuring and taking prompt

steps for recovery or sale of unviable accounts. The

salient features of the framework include: a) A Central

Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) has

been set up to collect, store and disseminate credit data

with respect to borrowers having aggregate fund-based

and non-fund based exposure of `50 million and above,

b) All commercial banks are required to mandatorily

report their credit information on their borrowers/

customers, c) NBFC-ND-SI, NBFCs-D and all NBFC-factors

(notified NBFCs, for short) are also required to furnish

such information, d) Banks were advised to furnish

details of all current accounts with outstanding balance

(debit or credit) of `10 million and above, and e) Banks

are required to monitor stress in borrowal accounts

through three categories of special mention accounts

(SMAs).

Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR): Taking into account

the final guidelines issued by BCBS, the Reserve Bank

issued its final guidelines on LCR, Liquidity Risk

Monitoring Tools and LCR Disclosure Standards’ in June

2014, keeping in view country-specific considerations as

well. Therefore, besides the usual phase-in arrangements

and definitional aspects, the guidelines by the Reserve

Bank also consider the range of high quality liquid assets

(HQLAs) available in Indian financial markets and their

liquidity features. As a result, investment in government

securities to the extent of 2 per cent of NDTL was

allowed to be included as level 1 HQLAs. Subsequently,

banks have now (with effect from January 1, 2015) been

permitted to reckon government securities held by

them up to another 5 per cent of their NDTL within the

mandatory SLR requirement as level 1 HQLAs. Further,

eligible common equity shares with 50 per cent haircut

have been allowed to be included as level 2B HQLAs.

Liquidity risk monitoring tools have also been suitably

prescribed in RBI’s standards. Accordingly, four

additional returns have been prescribed for banks: the

LCR, LCR by significant currencies, available

unencumbered assets, funding concentration and other

information on liquidity by banks.

Sale of NPAs to Asset Reconstruction Companies

(ARCs): In February 2014, as part of the Framework for

Revitalising Distressed Assets in the Economy, banks

have been allowed to: a) Reverse excess provision on

sale of NPAs to profit and loss account to the extent of

cash received on account of sale of NPAs is more than

the net book value of the NPAs, b) Amortise the loss on

sale of NPAs to ARCs where the sale consideration is

less than net book value (with regard to NPAs sold up to

March 31, 2015) over a period of two years, c) Sell

financial assets to Securitisation/Reconstruction

Companies (SCs/RCs) which are reported as SMA-2 by

the bank/FI to CRILC, and d) Use countercyclical/

floating provisions for meeting any shortfall on sale of

NPAs (i.e., when the sale is at a price below the net

book value). These measures are aimed at incentivising

banks to sell their NPAs to SCs/RCs, who in turn are

expected to act as a supportive system for stressed

asset management with greater emphasis on asset

reconstruction.

Depositor Education and Awareness (DEA) Fund

Scheme, 2014: Pursuant to the enactment of the

Banking Laws (Amendment) Act, 2012, a separate

section has been inserted in the Banking Regulation Act,

1949 relating to the Depositor Education and Awareness

(DEA) Fund. As per the scheme, which is applicable to

all commercial and co-operative banks in the country,

the amounts to be credited to the DEA Fund shall be the

credit balance in any deposit account maintained with a

bank which has not been operated for ten years or more,

or any amount remaining unclaimed for ten years or

more. The bank shall calculate the cumulative balances

in all such accounts, as on the day prior to the effective

date and transfer the amount to the DEA Fund on the

last working day of subsequent month along with the

accrued interest. The DEA Fund will be utilised for

promoting depositors’ interest and for such other

purposes which may be necessary for promoting

depositors’ interests as specified by the Reserve Bank

from time to time.

Draft guidelines for differentiated bank licences: The

final guidelines on payments banks and small banks

have been issued by the Reserve Bank (paragraphs 3.35

and 3.36).

Developments in cross-border supervision:

-

Basel core principles: In compliance with the FSAP

(2011) assessment of the Reserve Bank as

‘Materially Non-compliant’ in respect of three

Basel Core Principles (BCP) which include BCP 25

(Revised Principle 13) on ‘Home-Host

relationships’, the Reserve Bank has made

significant progress regarding supervisory

information sharing and cooperation with

jurisdictions where Indian banks are operating. As part of this process, the Reserve Bank has already

entered into 20 Memoranda of Understanding

(MoU) and one Letter for Supervisory Co-operation

with overseas regulators/supervisors.

-

Supervisory colleges: With a view to improving

cooperation and information exchange between

home and host supervisors, the Reserve Bank

arranged a supervisory college with respect to two

major Indian banks in 2013-14 (Bank of Baroda and

Bank of India). Supervisory colleges were hosted

earlier for State Bank of India and ICICI Bank

Limited in 2012-13.

-

Inspection of overseas branches/subsidiaries of

Indian banks: Global operations of Indian banks

are spread across 54 countries. In order to assess

the financial position, systems and control of

overseas branches, an inspection of eight banks in

five overseas jurisdictions covering almost 60 per

cent of the total overseas assets of Indian banks

was undertaken in 2012-13. In 2013-14, an

additional six banks in six jurisdictions covering

another 20 per cent of the asset ownership were

inspected.

Appointing NBFCs as Business Correspondents: To

hasten financial inclusion, the Reserve Bank has

undertaken certain measures including allowing

commercial banks to appoint NBFCs as Business

Correspondents (BCs) (only NBFCs-ND are eligible to act

as banks’ BCs). While appointing NBFCs as BCs, banks

have to ensure that their funds shouldn’t co-mingle with

those of the NBFCs. The banks also have to restrict

NBFCs-ND while functioning as BCs from adopting

practices such as offering savings or remittance functions

only to their own customers and avoiding the forced

bundling of services offered by them and the bank.

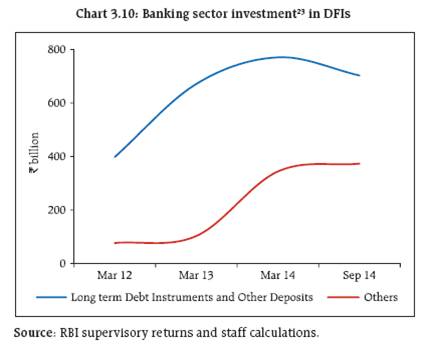

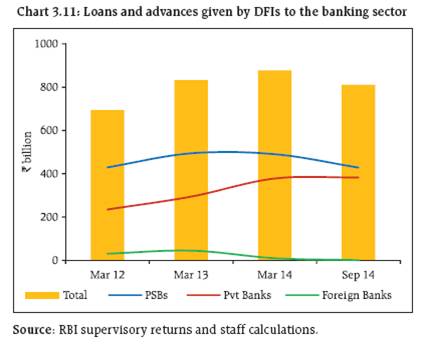

Development financial institutions: Dependence

on special funding dispensations

3.41 Development financial institutions (DFIs) like

National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development

(NABARD), Small Industries Development Bank of

India (SIDBI) and National Housing Bank (NHB), among others have been playing an important role

in the refinancing needs of banks and financial

institutions in niche sectors. The banks subscribe to

long term debt instruments issued by these

institutions and also avail refinance facilities from

them. However, certain peculiar features in the funding arrangements of DFIs may need a review in

the evolving regulatory and business scenario,

especially those pertaining to mandated contributions

by banks to some special funds like the Rural

Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF).22 The RIDF

and certain other special funds, mainly in the nature

of refinance funds, have been established within

these DFIs for providing financial assistance to

sectors such as micro, small and medium enterprises

(MSME) and housing, and to institutions such as cooperative

banks and regional rural banks (RRBs).

These funds are growing rapidly and now utilise a

major portion of shortfalls of the priority sector

lending of banks. The banking sector’s total

investment in long term bonds and special funds

taken together amounted to over ` 1 trillion as of

September 2014. Simultaneously, outstanding loans

and advances given by DFIs to the banking sector

were over `800 billion during the same period. This

indicates towards a possibility that a substantial

amount of funds originally dedicated by banks for

special purposes are getting back on to their balance

sheets (Charts 3.10 and 3.11).

Financial inclusion efforts by banks

3.42 The Reserve Bank had adopted financial

inclusion as one of its major projects in January 2010.

Subsequently, the financial inclusion initiative is

being led by a technical group on financial Inclusion

and financial literacy, under the FSDC sub-committee,

involving all financial sector regulators and other

government and non-government agencies. Banks

have been advised to devise financial inclusion plans

(FIPs) congruent with their business strategies and

comparative advantages to make them an integral part

of their corporate business plans. The initiative

included targets required to be set by banks for

opening banking outlets, Business Correspondent (BC)

outlets opened in urban locations, opening of basic

savings bank deposit accounts (BSBDAs), overdraft (OD) facility availed in BSBDAs and farm and nonfarm

credit such as Kisan Credit Cards/ General Credit

Cards (KCCs/GCCs) transactions in (Business

Correspondent – Information and Communication

Technology) (BC-ICT) accounts. Some important

points on progress made during the first half under

the financial inclusion plan for 2014-15 are provided

given in Box 3.3.

Convergence with the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan

Yojana (PMJDY)24

3.43 The objectives of PMJDY launched by the

Government of India are mostly in sync with the

financial inclusion objectives being advocated by the

Reserve Bank. The implementation plan for PMJDY

leverages on the policies laid down by the Reserve

Bank under financial inclusion. The comprehensive

FIP format devised by the Reserve Bank captures the

required data which is being used by banks to report

on the progress made under PMJDY also.

3.44 Going forward banks will have to revise their

targets set under FIPs so as to match with the targets allocated to them by the government under PMJDY.

The timeline for providing banking services in

villages with populations below 2,000 under the

roadmap may be advanced from March 2016 to

August 2015. With revised targets for opening of basic

bank accounts in place, banks will have to ensure

opening of at least one bank account in each

household by January 26, 2015.

3.45 While offering an overdraft facility of `5000,

banks will need to follow proper due diligence and

satisfactory operations in the account for six months.25

In addition, banks are advised to undertake financial

awareness campaigns in association with IBA so as to

educate customers with regard to the facilities offered

under the accounts opened under PMJDY.

Extending PMJDY to insurance and pension services

3.46 Given the low levels of penetration of

insurance and pension, there is a case for subsequently

extending or replicating a project on the lines of

PMJDY, to include the provision of insurance and

pension services for the common man.

Box 3.3: Financial Inclusion Plan: Progress up to September 2014

Progress made by domestic public and private sector

banks (including RRBs) under their financial inclusion

plan for the six month period from April 2014 to

September 2014 includes:

An increase of 62,948 banking outlets during the current

half year taking the total number of banking outlets to

446,752 as at the end of September 2014. BSBDAs reached

305 million for the half year ended September 2014

showing an increase of 62 million accounts during this

period. There was considerable increase in the opening

of BSBDAs during August/September 2014 in view of

government’s initiative under the Pradhan Mantri Jan

Dhan Yojana (PMJDY).

Nearly 57 million accounts had been opened under

PMJDY as at the end of September 2014. BC-ICT

transactions in BSBDAs showed steady progress with 220

million transactions for the half year ended September

2014 as against 329 million transactions recorded for

year ended March 2014.

KCCs which reflect flow of credit towards farm sector

entrepreneurial activities increased by 1.2 million during

the half year ended September 2014. GCCs which reflect

flow of credit towards non-farm sector entrepreneurial

activities increased by 1.3 million during the half year

ended September 2014. As at end September 2014, 8.8

million accounts were outstanding with a balance of

`1,165 billion.

Regulation of securities market

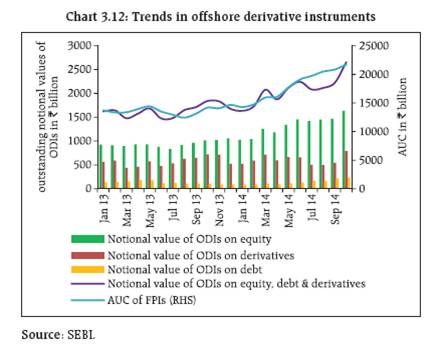

Trends in offshore derivatives instruments (ODIs)

3.47 Indian stock markets have seen rapid growth

during the last 2-3 quarters, reflecting the confidence

of investors in the fundamental strengths and

prospects of the Indian economy. While the

participation of the retail investor base still remains

comparatively narrow and shallow, the potential and

performance in terms of returns delivered by India’s

stock markets have been attracting substantial

amounts of foreign investments through offshore

derivatives instruments (ODIs).26

3.48 While foreign participation in Indian stock

markets adds to the depth and liquidity, it also

increases the risks of sudden episodes of heightened

volatility due to several global and domestic factors.

During the current phase of high growth in Indian

stock market valuations, investments through ODIs

also saw rapid growth and the notional values and

assets under custody touched the highest levels in

October 2014 (since 2008) (Chart 3.12).

3.49 The previous FSR had covered the major

changes in the regulatory framework for foreign

portfolio investors (FPIs) effected by the Securities

and Exchnage Board of India (SEBI) which was aimed

at, among other things, tightening the ‘know your

client’ norms for issuance of ODIs. The regulations

barred ‘unregulated’ foreign funds from dealing in

ODIs even though their investment managers were

under the regulation of their concerned regulators.

The regulations for FPIs have been further

strengthened with respect to requirements that the

entities subscribing to ODIs shall be from the

countries and jurisdictions which are members of

relevant international standards setting bodies like

International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) and Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

and signatories to relevant multilateral and bilateral

Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with SEBI.

Subscription to ODIs from residents in countries

identified in the public statement of the Financial

Action Task Force (FATF) has been prohibited as

compliance with international regulations for Anti-

Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of

Terrorism (AML/CFT).27 Entities having opaque structures have been prohibited from subscribing to

ODIs. Further the investment restrictions applicable

to FPIs which require that the purchase of equity

shares of each company by a single FPI or an investor

group shall be below 10 per cent of the total issued

capital of an Indian company, have been made

applicable to the ODIs also.

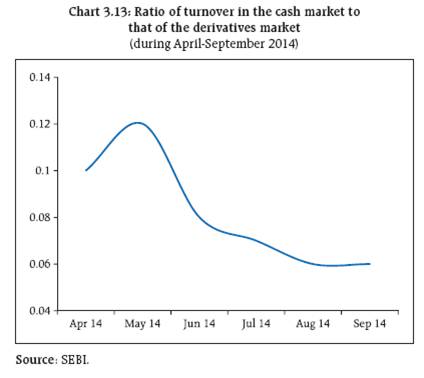

Faster growth in the derivatives segment of equity

markets

3.50 The previous FSR had raised the importance

of trends showing higher growth in the volumes of

equity derivatives as compared to that in cash market

segments. The ratio of turnover of cash markets to

that of derivatives markets continued its declining

trend during the first six months of the current

financial year 2014-15 (Chart 3.13).

Systemic risks from mutual funds: The Indian

context

3.51 The Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR)

(October 2014) observed that since 2007, mutual

funds (MFs), exchange traded funds (ETFs) and

households have become the largest owners of US

corporate and foreign bonds, accounting for 30 per

cent of the total holdings. Globally, from a financial

stability perspective, credit intermediation through

asset managers and markets has certain advantages

over that through banks, as the investment risk is

borne largely by investors and the liquidity is

provided mostly by markets. However, funds

investing in credit instruments have a number of

features that could result in elevated financial

stability risks. The previous FSR highlighted the

structural characteristics of the Indian mutual fund

industry which make it less prone to financial

stability risks with appropriate fencing provided by

SEBI regulations. Furthermore, retail participation in

the mutual fund industry is low as typically

corporates have a major share in the total Asset under

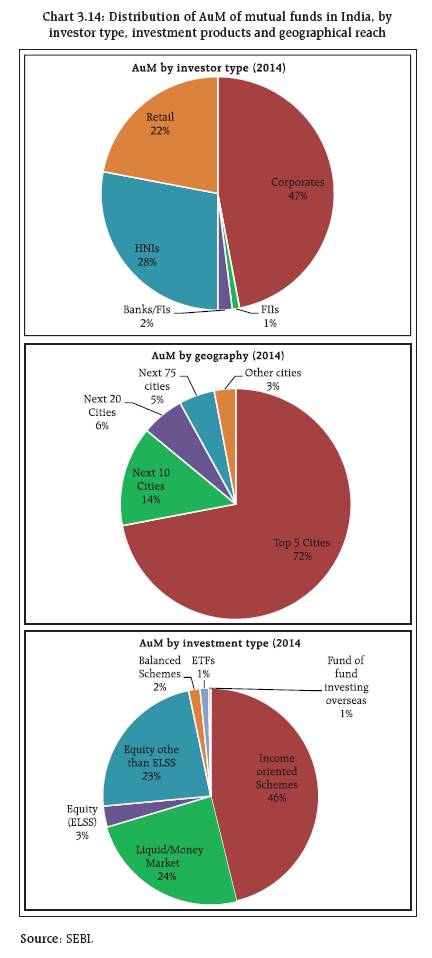

Management (AuM) which is around 47 per cent. In

addition, retail investors exhibit more ‘sticky’

behaviour in terms of holding to investments made

in mutual funds.

Holding pattern in the mutual fund industry

3.52 Across the globe, there is rich diversity in the

mutual fund sector as the asset management industry

offers a mix of traditional and alternative fund

products to a wide and diverse investor space

covering banks, corporate entities, insurance funds,

pension funds, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) and

high net worth individuals (HNIs)/retail investors.

The spread of Indian asset management is

comparatively limited and concentrated in terms of

investor categories, investment products and

geographical reach (Chart 3.14).

3.53 Corporates hold close to half of the total AuM

followed by HNIs and retail investors. The market is

highly concentrated as the five largest metropolitan

cities account for an almost three-fourth share of

total AuM. While the range of investment products

and fund schemes has expanded over the years,

income oriented schemes attract a major share of

investments followed by the liquid/money market

and growth oriented schemes. It has been observed

that in growth (equity) oriented schemes a major part

of the investment for the long term is by retail

investors, as compared to other investor categories.

3.54 The GFSR (October 2014), observed that the

risk of a run may be intensified by the increased

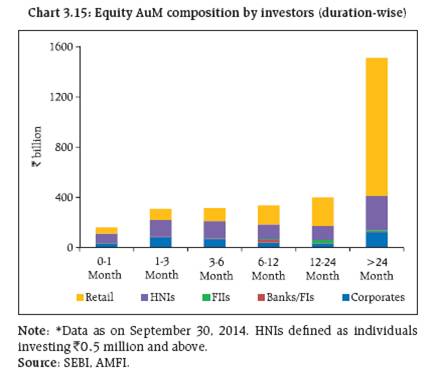

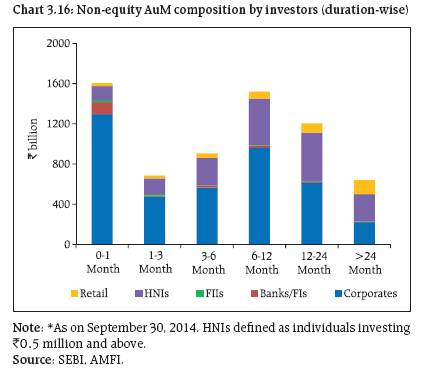

holdings of mutual funds.28 Shares of different

investors in composition of equity and non-equity

AuM in 2014 in different tenure holding baskets

ranging from extremely short term to long term,

indicates that in the Indian context retail investors

exhibit a tendency to hold mutual fund investments

for longer durations in the case of both equity as well

as non-equity investments (Charts 3.15 and 3.16).

This tendency of retail investors may also reveal their

vulnerability in falling behind the market when there

is a reversal in trend due to any reason, including

heavy selling by corporate or institutional investors. However, the principle of fair valuation adopted by

MFs as per SEBI’s directives in February 2012 ensures

fair treatment to all investors, existing as well as

those seeking to purchase or redeem units of MF

schemes. Adoption of this principle takes away the

incentive from investors to redeem prior to other

investors, thereby reducing the redemption pressure

on the scheme and risk of a run.

Concentration in equity portfolio holdings in

mutual funds across schemes by AMCs

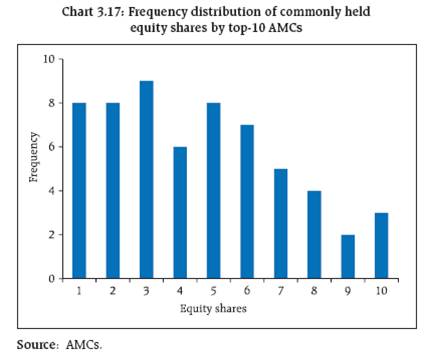

3.55 During the half year from April 2014 to

September 2014, deployment in equity by mutual

funds has surged about 50 per cent. There are 41

AMCs having AuM of `9,594.14 billion and the

distribution indicates a high degree of concentration

in the hands of a few AMCs, under a Pareto 80-20

principle. An analysis of portfolio holdings in equity

of the top ten AMCs29 along with their top ten

holdings in equity stocks shows that the portfolio

holdings of AMCs comprise quite a few common

stocks indicating preference towards a select group

of stocks (Table 3.4 and Chart 3.17).

Table 3.4: Select indicators on concentration in the

Indian mutual fund industry |

Equity AuM as percentage of total AuM |

31.6 |

Top-10 AMCs equity AuM as percentage of total equity AuM |

77.7 |

Top-10 stocks in each of top-10 AMCs/Total AuM of top-10 AMCs |

30.7 |

AuM of top-10 stocks overall as percentage of total equity AuM

of top-10 AMCs |

22.8 |

Share of equity AuM of top-4 AMCs as percentage of total

equity AuM |

49.0 |

| Source: AMCs. |

3.56 An analysis of the total exposure of top ten

AMCs to top ten stocks vis-à-vis the weightage of top

ten stocks (on the basis of market capitalisation) in

the index (CNX Nifty 100) also shows considerable

concentration levels in AMCs’ equity investments.

While top ten stocks account for 46 per cent of the

total market capitalisation of the index, the share of

top ten stocks in the AuM of top ten AMCs is around

74 per cent, indicating a strong preference towards

a select group of most liquid stocks. Although there

are regulations limiting the exposure of AMCs/

schemes to particular scrip, a significantly high degree

of concentration by the mutual fund sector may need

to be further monitored from a wider perspective of

its implications for stability and developing the

securities market.

Financial market infrastructure

3.57 As part of the Committee on Payment and

Settlement Systems (CPSS)30 and FSB, the Reserve

Bank is committed to implementing the CPSS-IOSCO

‘Principles for Financial Market Infrastructure’

(PFMIs). On the directions of the FSDC subcommittee,

an Inter-Agency Implementation Group

(IAIG) comprising members from the Reserve Bank,

SEBI and the Forward Markets Commission (FMC)

was constituted for monitoring the implementation

of PFMIs in India. The Clearing Corporation of India

Limited (CCIL) has been identified as an important

FMI under the regulation of the Reserve Bank.

Importance of cyber security and possible conflict

in priorities of PFMIs

3.58 With increasing use of electronic payments

and internet and mobile banking information

security and operational reliability challenges have

become very important from the financial stability

perspective. One of the clauses31 under PFMIs requires that an FMI operator’s business continuity

plans must ‘be designed to ensure that critical

information technology (IT) systems can resume

operations within two hours following disruptive

events’ and that there can be ‘complete settlement’

of transactions ‘by the end of the day of the

disruption, even in the case of extreme circumstances’.

However, a rush to comply with this requirement

may compromise the quality and completeness of

the analysis of causes and far-reaching effects of any

disruption. Restoring all the critical elements of the

system may not be practically feasible in the event

of a large-scale ‘cyber attack’ of a serious nature on a

country’s financial and other types of information

network infrastructures. This may also be in conflict

with Principle 16 of PFMIs which requires an FMI to

safeguard the assets of its participants and minimise

the risk of loss, as in the event of a cyber attack

priority may need to be given to avoid loss, theft or

fraudulent transfer of data related to financial assets

and transactions.

Legal entity identifiers for India

3.59 The Reserve Bank of India selected CCIL to

act as a local operating unit (LOU) for issuing globally

compatible legal entity identifiers (LEIs) in India.

Infrastructure in this regard has been set up, and the

use of LEI codes is likely to be mandated for OTC

derivatives transactions and large borrowers (legal

entities) in a phased manner.

Payment and settlement systems

Increasing use of electronic modes of transactions

3.60 The payment and settlement system

infrastructure in the country continued to perform

without any major disruptions. Development in the

system is evidenced by increasing use of electronic

modes of transaction settlements. Close to 90 per cent of the total settlement volumes was done

through retail electronic modes as of August 2014.

The share of paper-based clearing also declined

marginally over the last year (Charts 3.18 and 3.19).

Security issues and risk mitigation measures related

to ‘card not present’ transactions

3.61 Reserve Bank’s instructions on card

transactions’ security and risk mitigation, which have

been issued from time to time since 2009, mandate

the use of an additional factor of authentication (AFA)

for all ‘card not present’ (CNP) transactions. This was

earlier applicable to ‘card transactions’ in India with

cards issued by banks in India. Recently, instances

came to notice where entities, through adoption of

alternate business/payment models, were violating

these instructions on ‘card not present’ transactions

which were being effected without the mandated

additional authentication/validation even where the

underlying transactions were essentially taking place

between two residents in India.

3.62 In view of this, instructions were issued to

banks advising them that where cards issued by banks

in India are used for making ‘card not present’

payments towards purchase of goods and services

provided within the country, such transactions have

to be through a bank in India and the transaction

should necessarily be settled only in Indian currency

in adherence to extant instructions on security of

card payments as well as foreign exchange guidelines.

Core settlement guarantee fund, Default Waterfall

and Stress Test

3.63 Continuing with the objective ‘to promote

orderly and healthy growth of the securities market

in India’ along with safeguarding the markets from

systemic risks, SEBI has introduced a new layer of

safety net in the form of ‘core settlement guarantee

fund’ to mitigate risks from possible default in

settlement of trades and strengthen risk management

framework in the domestic capital markets.

3.64 The new structure aims at enhancing the

robustness of the present risk management system

of the clearing corporations to enable them to deal

with defaults of the clearing members much more

effectively. The granular norms related to core

settlement guarantee fund (SGF), stress testing and

default procedures would bring greater clarity and

uniformity as well as align the same with international

best practices while enhancing the robustness of the

present risk management system in the clearing

corporations (Box 3.4).

Box 3.4: SEBI Guidelines on Core SGF, Default Waterfall and Stress Test

SEBI has issued detailed guidelines on Core SGF,

Default Waterfall and Stress Test, with the following

objectives:

a) create a core fund (called core settlement guarantee

fund), within the SGF, against which no exposure is

given and which is readily and unconditionally

available to meet settlement obligations of clearing

corporation in case of clearing member(s) failing to

honour settlement obligation,

b) align stress testing practices of clearing corporations

with FMI principles (norms for stress testing for

credit risk, stress testing for liquidity risk and

reverse stress testing including frequency and

scenarios),

c) capture in stress testing, the risk due to possible

default in settlement of both institutional and non-institutional

trades,

d) harmonise default waterfalls across clearing

corporations

e) limit the liability of non-defaulting members in view

of the Basel capital adequacy requirements for

exposure towards Central Counterparties (CCPs),

f) ring-fence each segment of clearing corporation

from defaults in other segments, and

g) bring in uniformity in the stress testing and the risk

management practices of different clearing

corporations especially with regard to the default of

members.

The default waterfall in any segment will generally

follow the following order –

-

Monies of defaulting member

-

Insurance, if any

-

Clearing Corporations’ (CC) resources (equal to 5

per cent of MRC)

-

Core SGF (within it also penalties and then CC to

bear loss first to extent of 25 per cent of segment

MRC, then pro rata allocation to all contributors)

-

Proportion of remaining CC resources (excluding CC

contribution to core SGFs of other segments and

INR 100 Crore) equal to ratio of segment minimum

required corpus (MRC) to sum of MRCs of all

segments.

-

CC/Stock Exchange contribution to Core SGFs of

other segments and remaining CC resources to

extent approved

-

Capped additional contribution of non defaulting

members (pre-specified by CC)

-

Pro-rata haircut to pay-outs

Financial safety net: Deposit Insurance and

Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC)

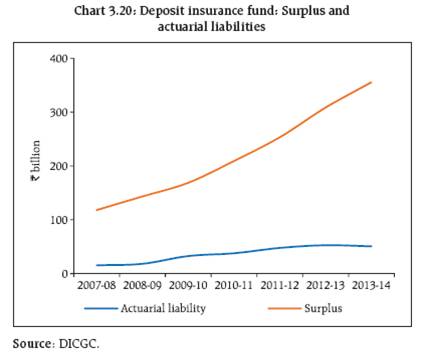

3.65 A strong deposit insurance system is a

necessary component of financial stability

arrangements in any jurisdiction. The previous FSRs

have highlighted some issues and challenges facing

the deposit insurance system in India which include,

inter alia, those related to the adequacy of the Deposit

Insurance Fund and coverage of deposit insurance,

apart from ensuring compliance with the Core

Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Systems.32

3.66 One of the core principles stresses on the

requirement for funding (including assured liquidity

funding) mechanisms necessary to ensure prompt

reimbursement of depositors’ claims and for banks

to bear the cost of deposit insurance. At present in

India, the DICGC maintains three distinct funds/

accounts: the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF), the

Credit Guarantee Fund (CGF), and the General fund

(GF). Out of these, DIF is primarily used for

settlement of claims from depositors and is sourced

out of the premium paid by the insured banks and