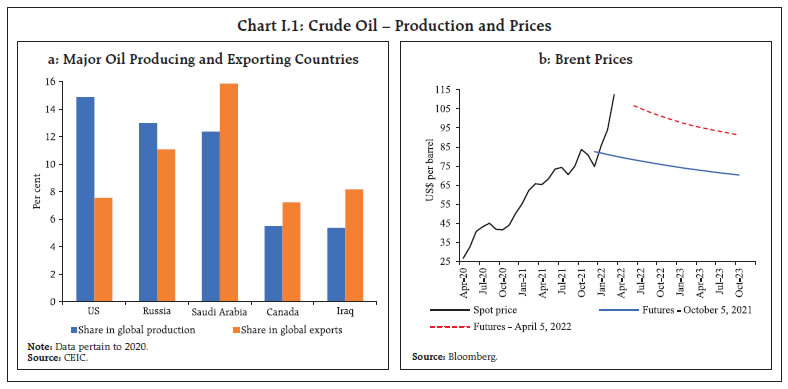

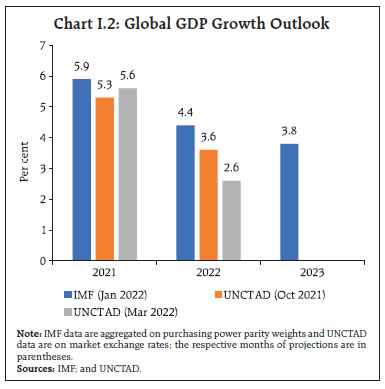

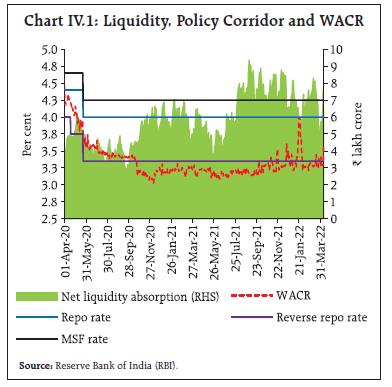

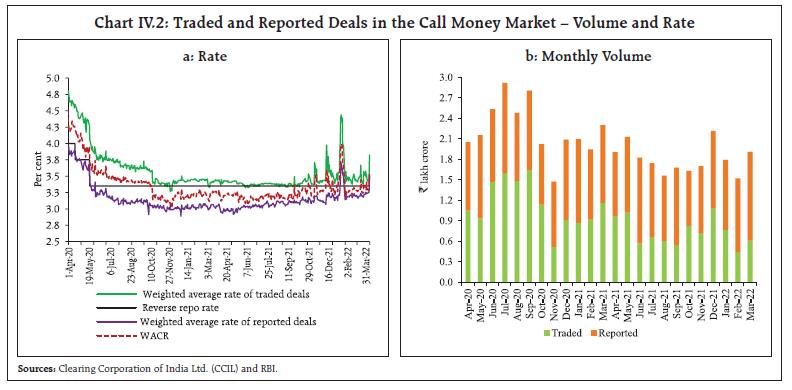

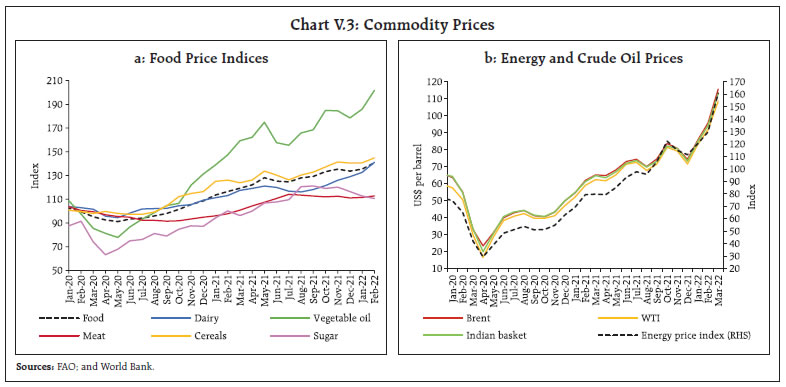

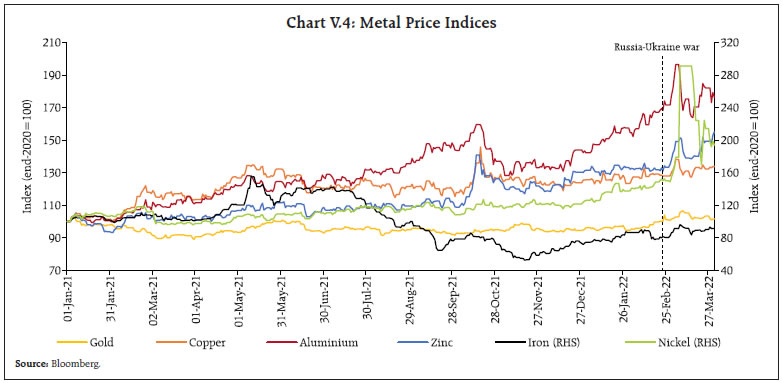

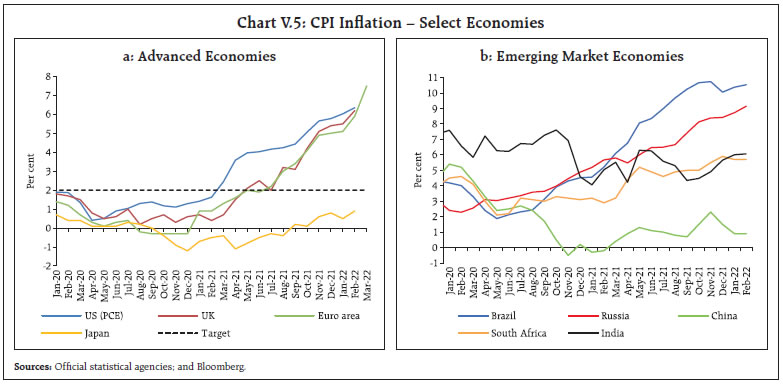

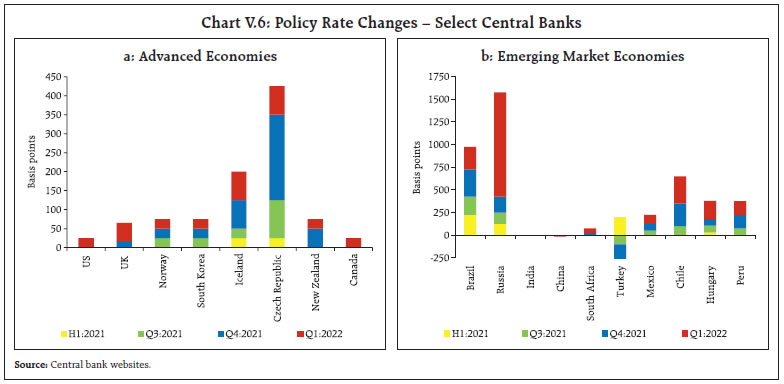

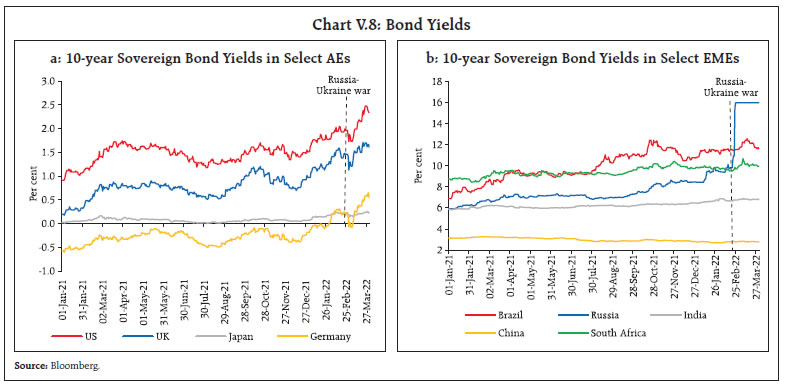

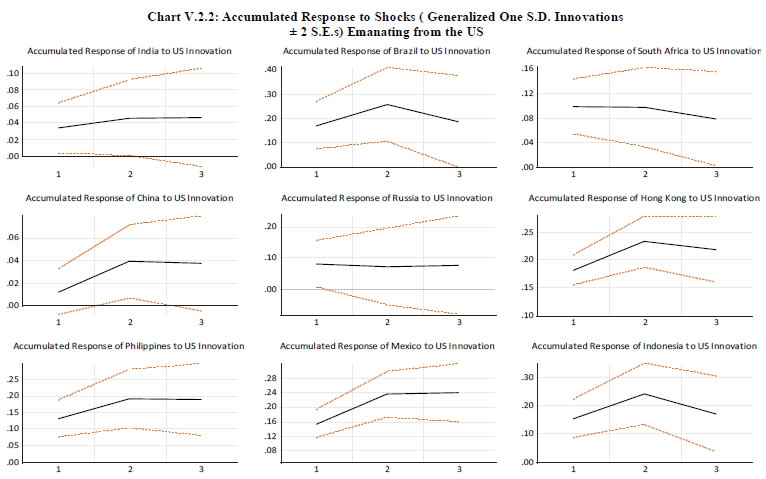

I. Macroeconomic Outlook The global economic environment has drastically altered, with the escalating geopolitical situation clouding the outlook for both growth and inflation in India and across the world warranting a revision in forecasts. Lingering war and sanctions, elevated oil and commodity prices, prolonged supply chain disruptions, accentuated global financial market volatility emanating from monetary policy shifts in major economies, and renewed waves of COVID-19 across countries pose downside risks to the growth and upside risks to the inflation outlook. I.1 Key Developments since the October 2021 MPR Since the release of the October 2021 Monetary Policy Report (MPR), the global economic environment has drastically altered, with the escalating geopolitical situation clouding the outlook for both growth and inflation in India and across the world warranting a revision in forecasts. Amidst persisting global supply chain disruptions, elevated energy and input prices and tighter labour markets, apprehensions of heightened global financial and commodity market volatility come together in a perfect storm. Brent crude prices crossed US$ 130 per barrel on March 8, 2022 and have hovered in the US$ 100-120 range since mid-March, posing the biggest risk to India’s economic prospects and putting the global recovery at heightened risk. The Bloomberg commodity index spiked by around 10 per cent since the war erupted on February 24 and 52 per cent on a year-on-year basis (as on April 5, 2022) as supply concerns exacerbated across commodities. Gold prices crossed US$ 2,000 per ounce on safe haven demand before some correction. Global food prices were at an all-time high in February 2022 and are expected to harden further in view of potential supply disruptions. With inflation turning out to be persistent and broad-based and well above targets, major advanced economies (AEs) quickened the pace of unwinding of their ultra-accommodative monetary policies. A number of emerging market economies (EMEs) have been in a tightening mode since 2021, and more are expected to follow. Sovereign bond yields in major AEs had hardened substantially in anticipation of a faster and steeper tightening of policy rates, but geopolitical risks have imparted high volatility as risk sentiment experiences sudden and sizeable shifts by every passing day. Equity markets have seen sharp corrections since the start of the calendar year with the market volatility index rising to a one-year high amidst geopolitical tensions. Currency markets have turned highly volatile in response to these developments, with the US dollar index reaching its highest since June 2020 due to flight to safety. Turning to the domestic economy, real gross domestic product (GDP) rose by 8.9 per cent in 2021-22, above its pre-pandemic (2019-20) level by just 1.8 per cent. Economic activity, which gained strength in Q2:2021- 22 (July-September) with the ebbing of the second wave, has lost pace since Q3:2021-22 (October- December), exacerbated by the spread of the Omicron variant in Q4 (January-March). The beneficial effects of the rapid ebb of infections have, however, been overwhelmed by the geopolitical conflagration since February 2022. Consumer price index (CPI) inflation edged above the upper tolerance band in February 2022 as unfavourable base effects combine with the onset of supply shocks as conflict escalates. While India’s direct trade and financial exposures are modest, indirect spillovers from the slowing global economy, the sharp jump in commodity prices across the board and elevated risk aversion and uncertainty owing to geopolitical developments weigh heavily on the outlook. Monetary Policy Committee: October 2021-March 2022 During October 2021-March 2022, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) met thrice. When the MPC met for its October 2021 meeting, CPI inflation had returned within the tolerance band after breaching the upper threshold in May-June 2021. The outlook for aggregate demand was progressively improving but output was still below the pre-COVID level and the recovery was uneven. The external environment had turned uncertain and challenging, with headwinds from slowing growth in major economies, a steep jump in natural gas prices and concerns emanating from normalisation of monetary policy in major advanced economies. Against this backdrop, the MPC noted that the domestic recovery needed to be nurtured assiduously through all policy channels and decided unanimously to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 4 per cent and by a majority of 5 to 1 to continue with an accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive and sustain growth on a durable basis and continue to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. In its December 2021 meeting, the MPC noted that continuing the normalisation of excise duties and value added taxes (VATs) on petroleum products alongside measures to address other input cost pressures assumed critical importance for a sustained lowering of core inflation. The domestic recovery was gaining traction but was just about catching up with pre-pandemic levels and downside risks remained significant, rendering the outlook highly uncertain, especially on account of global spillovers, the potential resurgence in COVID-19 infections with new mutations, persisting shortages and bottlenecks and the widening divergences in policy actions and stances across the world. Against this backdrop, the MPC judged that the ongoing domestic recovery needed sustained policy support to make it more broad-based and decided unanimously to maintain status quo on the policy repo rate and with a majority of 5 to 1 to continue with the accommodative stance set out in the October resolution. At the time of MPC’s February 2022 meeting, CPI inflation had edged even higher, driven up by unfavourable base effects while demand-pull pressures remained muted. The MPC noted that inflation was likely to moderate in H1:2022-23 and move closer to the target thereafter, providing room to remain accommodative. The potential pick up of input costs was seen as a contingent risk, especially if international crude oil prices remained elevated. On economic activity, the MPC observed that COVID-19 continued to impart some uncertainty to the future outlook while the global macroeconomic environment was characterised by deceleration in global demand, with increasing headwinds from financial market volatility induced by monetary policy normalisation. Judging that the domestic recovery was still incomplete and needed continued policy support, the MPC decided unanimously to keep the policy repo rate unchanged and on a 5 to 1 majority to continue with the accommodative stance. The MPC’s voting pattern reflects the diversity in individual members’ assessments, expectations and policy preferences, a characteristic also reflected in voting patterns of other central banks (Table I.1). Macroeconomic Outlook Chapters II and III analyse macroeconomic developments related to inflation and economic activity during H2:2021-22 (October-March). For the updated projections set out in this Chapter, the evolution of key macroeconomic and financial variables over the past six months warrants revisions in the baseline assumptions (Table I.2). First, international crude oil prices have surged over the past six months. Crude oil prices initially declined in late November 2021 in the wake of the Omicron wave and the expected reduction in demand; since then, global crude oil prices have been on the rise as demand increased with the ebbing of Omicron infections while supply remained sluggish due to the chronic under-performance versus targets by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) plus, a subdued shale response, multi-year low oil inventories, dwindling spare capacity and Russia- Ukraine developments (Chart I.1). The outlook has become highly uncertain due to escalating geopolitical tensions and sanctions, even as the US has decided to release about 180 million barrels of oil from its stockpile in a bid to cool crude prices. Taking into account these developments, crude prices (Indian basket) are assumed at US$ 100 per barrel in the baseline, 33 per cent above the October MPR baseline. | Table I.1 Monetary Policy Committees and Policy Rate Voting Patterns | | Country | Policy Meetings: October 2021-March 2022 | | Total meetings | Meetings with full consensus | Meetings without full consensus | Variation in policy rate (basis points) | | Brazil | 4 | 4 | 0 | 550 | | Chile | 4 | 4 | 0 | 550 | | Colombia | 4 | 0 | 4 | 300 | | Czech Republic | 4 | 0 | 4 | 350 | | Hungary | 6 | 6 | 0 | 275 | | India | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | | Israel | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | | Japan | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | | South Africa | 3 | 0 | 3 | 75 | | Sweden | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | | Thailand | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | | UK | 4 | 0 | 4 | 65 | | US | 4 | 3 | 1 | 25 | | Sources: Central bank websites. | Second, the nominal exchange rate (the Indian rupee or INR vis-à-vis the US dollar) has exhibited two-way movements in a range of INR 74-77 per US dollar since October 2021. The INR exhibited a depreciating bias till the middle of December 2021 over concerns about the economic fallout from the Omicron wave, elevated crude oil prices, and expectations of faster rate hikes by the US Fed. Subsequently, as the Omicron caseloads declined sharply, the INR showed signs of appreciation. The INR came under pressure from late February due to geopolitical tensions and the surge in crude oil prices. Taking these developments into consideration, the exchange rate is assumed at INR 76 per US dollar in the baseline as against INR 74.3 in the October 2021 MPR. | Table I.2: Baseline Assumptions for Projections | | Indicator | MPR October 2021 | MPR April 2022 | | Crude Oil (Indian basket) | US$ 75 per barrel during H2:2021-22 | US$ 100 per barrel during 2022-23 | | Exchange rate | ₹74.3/US$ during H2:2021-22 | ₹76/US$ during 2022-23 | | Monsoon | 1 per cent below long-period average | Normal for 2022-23 | | Global growth | 6.0 per cent in 2021

4.9 per cent in 2022 | 3.5 per cent in 2022

3.5 per cent in 2023 | | Fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | To remain within BE 2021-22

Centre: 6.8

Combined: 10.2 | To remain within BE 2022-23

Centre: 6.4

Combined: 9.0 | | Domestic macroeconomic/ structural policies during the forecast period | No major change | No major change | Notes: 1. The Indian basket of crude oil represents a derived numeraire comprising sour grade (Oman and Dubai average) and sweet grade (Brent) crude oil.

2. The exchange rate path assumed here is for the purpose of generating the baseline projections and does not indicate any ‘view’ on the level of the exchange rate. The Reserve Bank is guided by the objective of containing excess volatility in the foreign exchange market and not by any specific level of and/or band around the exchange rate.

3. BE: Budget estimates.

4. Combined fiscal deficit refers to that of the Centre and States taken together.

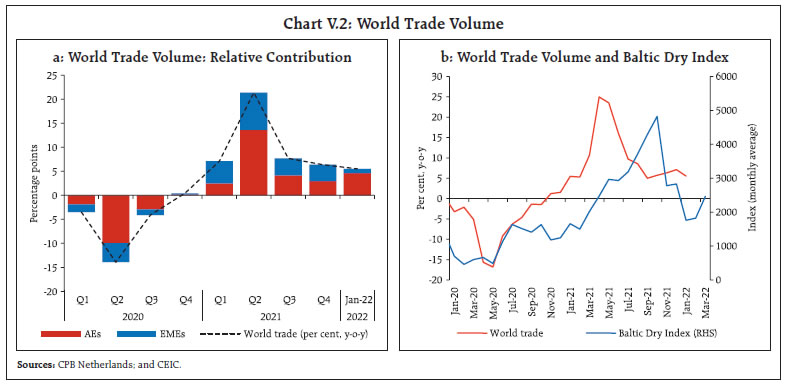

Sources: RBI staff estimates; Budget documents; and IMF. | Third, the global economic prospects have weakened significantly since the October MPR, with a sequence of headwinds from the Omicron wave, prolonged global supply chain disruptions, persistent container shortages, multi-decadal inflation highs in major advanced economies forcing their central banks to quicken the pace of monetary policy normalisation and more recently by the escalating geopolitical tensions (Chart I.2). According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the rise in commodity prices and financial market volatility since the ratcheting up of the geopolitical tensions in February, if sustained, could reduce global GDP growth by over one percentage point in the first year and push up global consumer price inflation by around 2.5 percentage points; the output losses could be higher in case of further sanctions, consumer and business boycotts, disruptions to shipping and air traffic, the unavailability of key products from Russia, trade restrictions such as export bans on food commodities, and undermined consumer confidence.1 In March, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) projected global growth for 2022 to be 100 bps below its October 2021 assessment.2

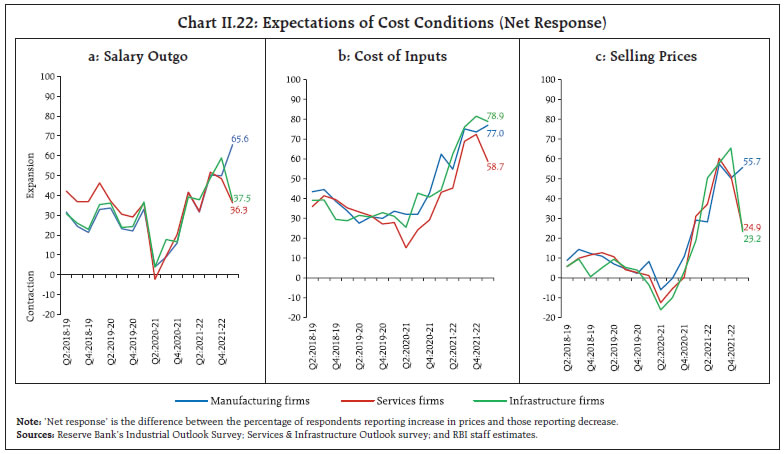

I.2 The Outlook for Inflation After easing to 4.3 per cent in September 2021, CPI inflation rose in the following months to reach 6.1 per cent in February 2022, driven by the increase in food inflation. Looking ahead, the three months and one year ahead median inflation expectations of urban households increased marginally by 10 bps each in the March 2022 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey.3 The proportion of respondents expecting the general price level to increase by more than the current rate also increased for both the three months and one year ahead horizons vis-à-vis the previous round (Chart I.3). Manufacturing firms polled in the January-March 2022 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey expected increase in their input costs and selling prices in Q1:2022-23 (Chart I.4a).4 Service and infrastructure sector companies expected moderation in the pace of increase in input costs and selling prices in Q1:2022-23 (Charts I.4b and I.4c).5 The respondents in manufacturing and services PMI reported continued input and output price pressures in March 2022.

Professional forecasters surveyed by the Reserve Bank in March 2022 expected CPI inflation to move from 6.1 per cent in Q4:2021-22 to 5.8 per cent in Q1:2022-23, 5.9 per cent in Q2, 5.4 per cent in Q3 and 5.2 per cent in Q4 (Chart I.5 and Table I.3).6 One-year ahead inflation expectations of professional forecasters are anchored around the inflation target, while those of households seem to be sensitive to volatility in food prices (Box I.1). | Table I.3: Projections - Reserve Bank and Professional Forecasters | | (Per cent) | | | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | | Reserve Bank’s Baseline Projections | | | | | Inflation, Q4 (y-o-y) | 6.2 | 5.1 | 5.5 | | Real GDP growth | 8.9@ | 7.2 | 6.3 | | Median Projections of Professional Forecasters | | Inflation, Q4 (y-o-y) | 6.1 | 5.2 | | | Real GDP growth | 8.8 | 7.5 | | | Gross domestic saving (per cent of GNDI) | 29.0 | 28.7 | | | Gross capital formation (per cent of GDP) | 30.1 | 30.6 | | | Credit growth of scheduled commercial banks | 8.0 | 9.4 | | | Combined gross fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | 10.4 | 9.7 | | | Central government gross fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | 6.9 | 6.4 | | | Repo rate (end-period) | 4.0 | 4.5 | | | Yield on 91-days treasury bills (end-period) | 3.9 | 4.5 | | | Yield on 10-year central government securities (end-period) | 6.8 | 7.1 | | | Overall balance of payments (US$ billion) | 42.5 | -18.1 | | | Merchandise exports growth | 39.0 | 8.9 | | | Merchandise imports growth | 53.0 | 12.9 | | | Current account balance (per cent of GDP) | -1.7 | -2.6 | | @: Second advance estimates, National Statistical Office.

Note: GNDI: Gross National Disposable Income.

Sources: RBI staff estimates; and Survey of Professional Forecasters (March 2022). |

Box I.1: Inflation Expectations Anchoring Inflation expectations of firms and households are a key determinant of actual inflation dynamics. Two facets of the degree of anchoring of inflation expectations can be empirically examined – shock and level anchoring (Ball and Mazumder, 2011; Chen, 2019). Shock anchoring would imply that transitory supply-side shocks and inflation surprises (difference between the realised inflation and prior inflation expectations) do not affect inflation expectations of economic agents (equations 1 and 2 below). Level anchoring – a stronger form of the hypothesis – assesses directly whether inflation expectations are anchored at the inflation target (equation 3 below). Drawing upon this conceptual framework, an empirical analysis is undertaken for 4-quarter ahead inflation expectations of professional forecasters (SPF) and households (IESH) in the Indian context for the period October 2016 to February 2022. The analysis is also conducted for the pre-pandemic period for robustness, given the persistent supply-side shocks in the period since March 2020. | Table I.1.1: Shock Anchoring | | | SPF | IESH | | FIT period | FIT period excluding pandemic | FIT period | FIT period excluding pandemic | | Core inflation | 0.244** | 0.240* | 0.233** | 0.214** | 0.687*** | 0.596** | 0.657*** | 0.743*** | | Food and fuel inflation | -0.013 | - | -0.024 | - | 0.156** | - | 0.399*** | - | | Food inflation | - | -0.012 | - | -0.020 | - | 0.130** | - | 0.288*** | | Fuel inflation | - | 0.013 | - | 0.015 | - | 0.079 | - | 0.025 | | Constant | 3.242*** | 3.183*** | 3.397*** | 3.418*** | 5.411*** | 5.602*** | 4.628*** | 4.545*** | | Observations | 33 | 33 | 21 | 21 | 33 | 33 | 21 | 21 | | Adjusted R2 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.51 | | DW Statistic | 1.56 | 1.59 | 1.47 | 1.49 | 1.86 | 1.82 | 2.00 | 1.92 | Note: ***, **, * denote the level of significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. Regression estimates are corrected for first-order serially correlated residuals by using the Prais–Winsten transformation. FIT refers to Flexible Inflation Targeting.

Source: RBI staff estimates. |

One-year ahead expectations of professional forecasters are also level-anchored (i.e., they remain in close proximity to the inflation target); the null hypothesis of a unit coefficient on the inflation target and a zero coefficient on the actual realisation of inflation is not rejected (Table I.1.3 and Chart I.1.1a). Such anchoring of medium- and long-term inflation expectations can impart stability to bond yields and improve monetary transmission. Inflation expectations of households, on the other hand, seem to be adaptive and backward-looking, driven by changes in food prices (food items have a weight of 46 per cent in the CPI in India) as well as the relatively more volatile nature of food prices (Singh et al., 2022). A comparison of the regressions of households for the full period and the pre-pandemic period (Tables I.1.1 and I.1.2) indicates a reduction in the coefficients on food and fuel inflation as well as on inflation surprises in the extended sample, suggesting reduced sensitivity of their expectations to shocks. An upward bias in households’ inflation expectations is observed in other countries as well (Chart I.1.1.b). The co-movement of households’ inflation expectations with actual inflation appears to be in consonance with the cross-country experience with expectations responding more to an increase in prices than to an equivalent fall in prices (Baqaee, 2020). | Table I.1.2: Shock Anchoring | | | SPF | IESH | | FIT period | FIT period excluding pandemic | FIT period | FIT period excluding pandemic | | News shock | 0.082 | 0.030 | 0.219** | 0.442** | | Constant | -0.014 | -0.052 | 0.969** | 1.896** | | Observations | 33 | 21 | 33 | 21 | | Adjusted R2 | 0.03 | -0.04 | 0.08 | 0.15 | | DW Statistic | 1.61 | 1.52 | 2.27 | 2.26 | Note: ***, **, * denote the level of significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

Source: RBI staff estimates. |

| Table I.1.3: Level Anchoring | | | SPF | IESH | | FIT period | FIT period excluding pandemic | FIT period | FIT period excluding pandemic | | Target | 1.082*** | 1.118*** | 2.228*** | 1.574*** | | Inflation | 0.027 | -0.017 | 0.169 | 0.711*** | | Observations | 33 | 21 | 33 | 21 | | Adjusted R2 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.00 | | DW Statistic | 1.54 | 1.18 | 1.96 | 1.84 | | Wald Test for β1=1 & β2=0 (p-value) | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Note: ***, **, * denote the level of significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. Regression estimates are corrected for first-order serially correlated residuals by using the Prais–Winsten transformation.

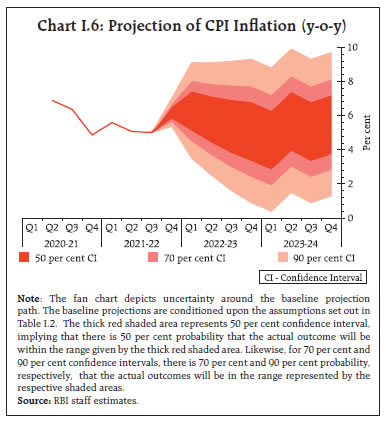

Source: RBI staff estimates. | References: Ball, Laurence, and S. Mazumder (2011), “Inflation Dynamics and the Great Recession”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 42 (Spring), pp. 337–405. Baqaee, David Rezza (2020), “Asymmetric Inflation Expectations, Downward Rigidity of Wages, and Asymmetric Business Cycles”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 114, pp. 174-193. Chen, Yiqun Gloria (2019), “Inflation, Inflation Expectations, and the Phillips Curve';, Congressional Budget Office Working paper, 2019-07. Singh, D. P., Mishra, A., and Shaw, P. (2022), “Taking Cognisance of Households’ Inflation Expectations in India”, RBI Working Paper Series, 02/2022. | Looking ahead, the record foodgrains production in 2021-22, ample foodgrains buffer stocks and the government’s supply side interventions augur well for food inflation in 2022-23 on the assumption of a normal monsoon. Taking into account the initial conditions, signals from forward-looking surveys, estimates from structural and other time-series models, and crude oil (Indian basket) at US$ 100 per barrel in 2022-23, CPI inflation is projected to average 5.7 per cent in 2022-23 – 6.3 per cent in Q1, 5.8 per cent in Q2, 5.4 per cent in Q3, and 5.1 per cent in Q4 (Chart I.6). The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for headline inflation in Q4:2022-23 are 3.4-6.8 per cent and 2.5-7.7 per cent, respectively. For 2023-24, assuming a progressive normalisation of supply chains, a normal monsoon and no further exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates indicate that inflation will move in a range of 4.6-5.7 per cent. The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for Q4:2023-24 are 3.8-7.2 per cent and 2.9-8.1 per cent, respectively.  There are a number of upside and downside risks to the baseline inflation forecasts. The upside risks emanate from a further hardening of global crude and other commodity prices due to geopolitical tensions, longer-than-expected supply chain disruptions, a larger pass-through of input cost pressures to output prices in the event of stronger demand conditions and global financial market volatility from a quicker-than- expected normalisation of monetary policy by the advanced economies. The downside risks arise from an early mending of supply chain disruptions, a muted pass-through to output prices and a correction in global commodity prices due to global demand weakening more than expected and an easing of geopolitical tensions. I.3 The Outlook for Growth Economic activity which was recovering with the ebbing of the third wave, rapid stride towards universal vaccination, and supportive fiscal and monetary policies now faces significant headwinds from the exacerbating geopolitical developments and the accompanying sharp rise in global commodity prices and weakening global growth outlook. Turning to the key messages from forward-looking surveys, the consumer confidence (the current situation index) rose in the March 2022 survey round, although it remained in the pessimistic zone. For the year ahead, consumers’ optimism strengthened further on the back of improved sentiments on the general economic situation, employment and household income (Chart I.7).8

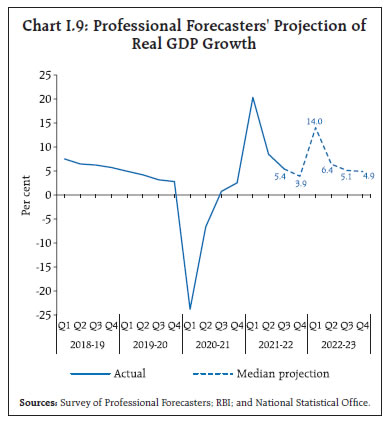

Optimism in the manufacturing sector for the quarter ahead moderated marginally in the January-March 2022 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey due to an ebb in sentiments on inventory of raw materials and finished goods (Chart I.8a). Services and infrastructure sectors also reported lower optimism on the overall business situation in Q1:2022-23 (Charts I.8b and I.8c). Recent surveys by other agencies indicate a sequential moderation in business expectations (Table I.4). According to the PMI surveys, one year ahead business expectations of firms in the manufacturing sector moderated while those of firms in the services sector remained steady in March 2022. Professional forecasters polled in the March 2022 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey expected real GDP growth at 3.9 per cent in Q4:2021-22, 14.0 per cent in Q1:2022-23 (due to favourable base effects), 6.4 per cent in Q2, 5.1 per cent in Q3, and 4.9 per cent in Q4 (Chart I.9). | Table I.4: Business Expectations Surveys | | Item | NCAER Business Confidence Index

(December 2021) | FICCI Overall Business Confidence Index

(January 2022) | Dun and Bradstreet Composite Business Optimism Index

(February 2022) | CII Business Confidence Index

(March 2022) | | Current level of the index | 124.4 | 63.9 | 89.9 | 65.0 | | Index as per previous survey | 117.4 | 75.7 | 94.6 | 66.8 | | % change (q-o-q) sequential | 6.0 | -15.6 | -5.0 | -2.7 | | % change (y-o-y) | 46.6 | -13.9 | 12.5 | -5.4 | Notes: 1. NCAER: National Council of Applied Economic Research.

2. FICCI: Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry.

3. CII: Confederation of Indian Industry.

Sources: NCAER; FICCI; CII; and Dun & Bradstreet Information Services India Pvt. Ltd. |  Taking into account the baseline assumptions, including crude oil (Indian basket) at US$ 100 per barrel, the survey indicators, and model forecasts, real GDP growth is expected at 7.2 per cent in 2022- 23 - Q1:2022-23 at 16.2 per cent; Q2 at 6.2 per cent; Q3 at 4.1 per cent; and Q4 at 4.0 per cent - with risks evenly balanced around this baseline path (Chart I.10 and Table I.3). For 2023-24, assuming a normal monsoon, and no major exogenous or policy shocks, the structural model estimates indicate real GDP growth at 6.3 per cent, with quarterly growth rates in the range of 5.9-6.8 per cent. There are upside and downside risks to the baseline growth path. Upside risks to the baseline trajectory could emanate from stronger and sustained expansion in domestic demand, including for contact-intensive services, a boost to private investment activity from the confluence of government’s thrust on capital expenditure, and healthier corporate balance sheets (Chapter III). On the contrary, the heightened geopolitical tensions – resulting in the significant hardening of international crude oil and other commodity prices to multi-year highs, the upsurge in global financial market turmoil and the loss of momentum in global trade and demand – pose sizeable downside risks to the baseline growth path. Additional downside risks emanate from renewed COVID-19 infections, new and more contagious variants of the virus, pandemic-related global supply bottlenecks stretching longer than expected, and AE monetary policy normalisation-induced global financial market volatility. I.4 Balance of Risks The baseline projections of inflation and growth presented in the previous sections are conditional on the assumptions of key domestic and international macroeconomic variables set out in Table I.2. This section explores plausible alternative scenarios to assess the balance of risks to the baseline projections. (i) Geopolitical Risks The global recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is turning out to be muted relative to earlier expectations. Downside risks to even this subdued recovery have jumped significantly from the escalation of geopolitical tensions, which have led to a broad-based increase in global commodity prices and are expected to have a large negative impact on global trade and growth. Even as the share of Russia and Ukraine in global economy is modest, they are among the major global suppliers of key commodities such as crude oil, natural gas, fertilisers, wheat, corn, and metals. A more protracted conflict, extended sanctions, sustained further hardening of global commodity prices and prolonged supply bottlenecks could push global growth well below the baseline. Recurrent waves of COVID-19 infections amidst new mutants of the virus, uneven vaccination progress across countries, and a sharper and deeper tightening of monetary policy by major AE central banks to anchor inflation expectations impose further downside risks to the global outlook. In such a scenario, if global growth is 100 bps lower than the baseline, domestic growth and inflation could be around 40 bps and 20 bps, respectively, below the baseline trajectories; however, the jump in crude oil prices due to geopolitical tensions, as discussed later, would harden domestic inflation. Conversely, an early easing of geopolitical tensions, growing vaccination coverage across countries, a more even distribution of vaccines towards low-income countries, a faster easing of supply chain disruptions and a more gradual withdrawal of monetary accommodation by the major AEs could provide a boost to economic activity. In this scenario, assuming that global growth surprises by 100 bps on the upside, domestic growth and inflation could edge higher by around 40 bps and 20 bps, respectively, over the baseline (Charts I.11a and I.12a). (ii) International Crude Oil Prices International crude oil prices have risen sharply, driven by sudden and overwhelming disruptions caused by war, strong demand and a less than proportionate expansion in output by the OPEC plus. While future prices and the medium-term outlook for supplies suggest a correction in crude oil prices in the months ahead, this could easily be overwhelmed by the fallout of the conflict. The outlook poses sizeable risks on either side for a net energy importer like India. An escalation of geopolitical tensions and further drawdown of global inventories amidst OPEC plus production continuing to lag demand could harden international crude oil prices even further and US$ 150 per barrel could easily be tested.

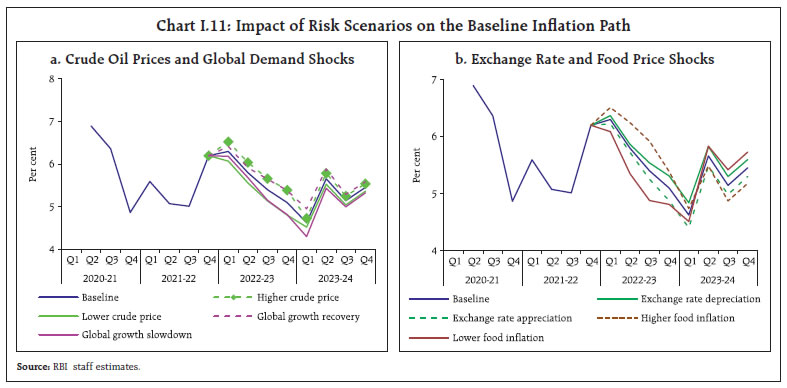

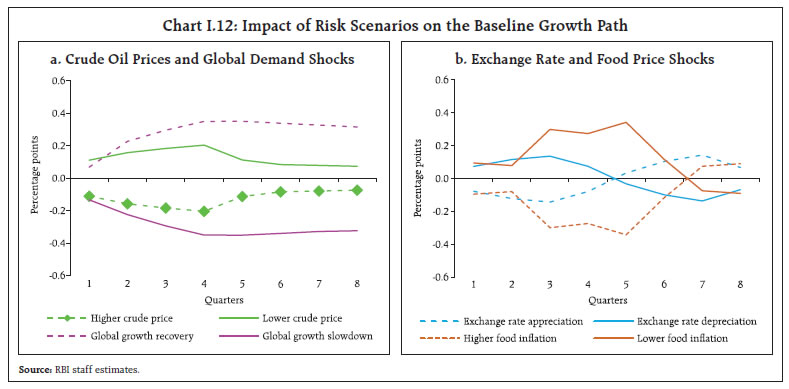

Assuming crude oil price to be 10 per cent above the baseline of US$ 100 per barrel, domestic inflation and growth could be higher by around 30 bps and weaker by around 20 bps, respectively, over the baseline. Conversely, crude oil prices could soften below the baseline due to a faster resolution of geopolitical tensions, release of emergency stockpiles, a stronger shale production response, and global demand becoming subdued owing to renewed waves of the virus. As a result, if the Indian basket of crude prices falls by 10 per cent relative to the baseline, inflation could ease by around 30 bps with a boost of 20 bps to growth (Charts I.11a and I.12a). Crude oil prices impact growth and inflation through multiple channels. First, international crude prices have a direct impact on inflation, given the weights of petrol and diesel in the CPI basket, which wear off in a year. Second, indirect effects through cost push and higher inflation expectations could push up headline inflation in the medium run. Third, higher trade and current account deficits in the balance of payments can exert downward impact on the INR exchange rate, adding to inflationary pressures. On the output side, higher petroleum prices act as a negative terms of trade shock to the economy, reduce the consumption of non-oil items of households and lower profit margins of firms, cash flows and investment. The consequent moderation in aggregate demand helps to offset some of the inflationary pressures. On net, inflation increases and might attract a monetary policy response (Chart I.13). The impact of crude oil prices on domestic inflation and output is also conditional on the initial level of crude oil prices in view of the retail petroleum product prices containing specific (non-ad valorem) elements such as excise duty and refining costs which do not co-move with crude oil prices. Therefore, the higher the initial level of crude oil prices, the higher is the impact of a given shock on domestic headline inflation, imparting non-linearity and time variations (Chart I.14). Finally, the impact of crude oil prices on the domestic economy would also be dependent on the persistence of the oil shock. A transitory shock to crude oil prices (Scenario 1) has only a negligible and temporary impact on inflation and output, while the adverse impact can be substantially higher and more protracted in case crude oil prices remain at elevated levels for longer (Scenarios 2 and 3) (Chart I.15).

(iii) Exchange Rate The INR has exhibited two-way movements over the past six months, reflecting both global and domestic factors. Looking ahead, the protracted geopolitical tensions, the heightened volatility in global financial markets, elevated global sovereign bond yields on the back of more than currently anticipated monetary policy tightening in major AEs, and new COVID-19 mutations could lead to a broader risk aversion towards EME assets and net capital outflows. Such developments can put downward pressure on the INR. Should the INR depreciate by 5 per cent from the baseline, inflation could edge up by around 20 bps while GDP growth could be higher by around 15 bps through increased net exports; the exchange rate pass-through to inflation can, however, be non-linear and time-varying in an environment of high volatility in financial and commodity markets (Patra et al, 2018).9 On the other hand, given that India is among the fastest growing large economies with relatively better growth outlook, strong capital flows led by foreign direct investment could continue. In this scenario, if the INR appreciates by 5 per cent relative to the baseline, inflation and GDP growth could moderate by around 20 bps and 15 bps, respectively (Charts I.11b and I.12b). (iv) Food Inflation Food inflation has risen in recent months, largely due to adverse base effects. The expected seasonal correction seems to be getting backloaded. Going forward, however, robust rabi prospects, ample buffer stocks of cereals, easing of supply chain bottlenecks and effective supply management measures could soften food inflation more than anticipated, and push headline inflation 50 bps below the baseline. Conversely, hardening global food prices due to geopolitical tensions and domestic demand-supply gaps in key food items like pulses and edible oils could lead to upward pressures on food prices and raise headline inflation by around 50 bps. The baseline assumes a normal south-west monsoon in 2022 and any deviations in the actual outturn on either side as well as unseasonal rains would be a critical factor for the food as well as headline inflation trajectory (Charts I.11b and I.12b). I.5 Conclusion Economic activity was recovering from the ebbing of the Omicron wave when the fallout of the Ukraine- Russia conflict has overcast the near-term outlook with heightened uncertainties. Growth and inflation outcomes are at high risk across the world as well as in India. In the face of this extraordinary risk, the positive effects expected from the release of pent-up demand, especially for contact-intensive services, the government’s thrust on infrastructure and capital expenditure, congenial financial conditions and improving capacity utilisation appear ephemeral. Updated forecasts indicate that headline inflation, which was expected to ease from current elevated levels as food inflation gets contained on the back of record production and abundant stocks, is now subject to a large geopolitical shock. The escalation of war, continued supply chain disruptions, global financial market volatility emanating from monetary policy normalisation in major advanced economies and the evolving COVID-19 trajectory pose downside risks to growth and upside risks to the inflation outlook and could get exacerbated significantly by the intensification of geopolitical tensions. The concomitant surge in global oil and commodity prices to multi-year highs has increased risk aversion as reflected in jumps in financial market volatility and these developments could increasingly shape the economic prospects globally and for India.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

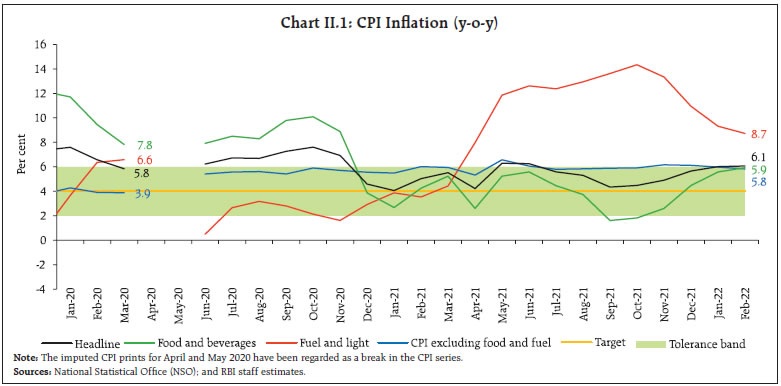

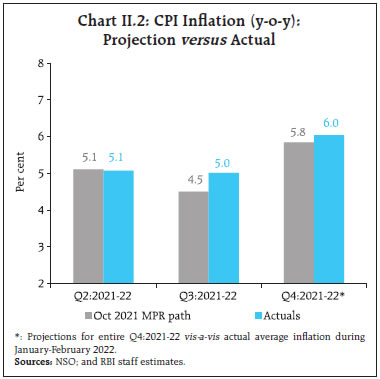

II. Prices and Costs Consumer price index (CPI) inflation remained volatile during September 2021 to February 2022. After moderating close to the target rate in September, headline CPI inflaiton rose sequentially to the upper tolerance threshold during January-February 2022 mirroring the movements in food inflation, even as fuel inflation remained elevated and core inflation sticky. Costs of farm and non-farm inputs remained elevated. Growth in nominal rural wages for both agricultural and non-agricultural labourers as well as staff costs in the organised sector remained contained. Since the publication of the October 2021 MPR, headline inflation1 has registered two-way movements – first, it moderated close to the target at 4.3 per cent in September 2021; thereafter, it moved up sequentially to the upper tolerance threshold of 6 per cent in January 2022, breaching it at 6.1 per cent in February. The movements in headline inflation mirrored the sharp movements in food inflation, which oscillated between a low of 1.6 per cent in September 2021 and a peak of 5.9 per cent in February 2022. A combination of transitory supply dislocation shocks, elevated import price pressures and unfavourable base effects drove the surge in food inflation. With international petroleum product prices on an unrelenting upward trajectory, fuel group inflation remained in double digits during September to December, moderating a little to 9.3 per cent in January 2022 and further to 8.7 per cent in February. Core inflation2 has remained elevated, sticking close to the upper tolerance threshold of 6.0 per cent as cost-push pressures impacted both manufactures and services (Chart II.1). The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual inflation outcomes from projections, if any, and explain the underlying reasons thereof. The October 2021 MPR projected inflation to moderate to 4.5 per cent in Q3:2021-22 before increasing to 5.8 per cent in Q4:2021-22. Actual inflation outcomes were higher than projections by around 50 bps in Q3, but the gap narrowed to 20 bps in Q4 (Chart II.2). The overshoot in Q3 was primarily on account of vegetables prices shooting up disproportionately and falling out of alignment with projections in the months of October-November 2021 as a result of crop damage from heavy unseasonal rainfall. In addition, crude oil prices, which were assumed to be at US$ 75 per barrel during H2:2021-22, averaged US$ 82 per barrel in October itself, pushing domestic pump prices to the then historic high levels3 by the beginning of November. Subsequent reductions in excise duties and State value-added taxes (VATs) in early November led to a reduction in pump prices. Thereafter, barring tax cuts, pump prices remained unchanged in rest of Q3 even as crude oil prices moderated. In Q4 (up to February 2022), actual outcomes have turned out to be closer to projections, as the seasonal correction in some vegetable prices materialised as anticipated; but it turned out to be shallower, resulting in the overshoot over projections. Moreover, cereal prices were provided some upside, by rising export unit values – India is the world’s largest exporter of rice; it has also exported 19.1 million tonnes of rice during April 2021 to February 2022.

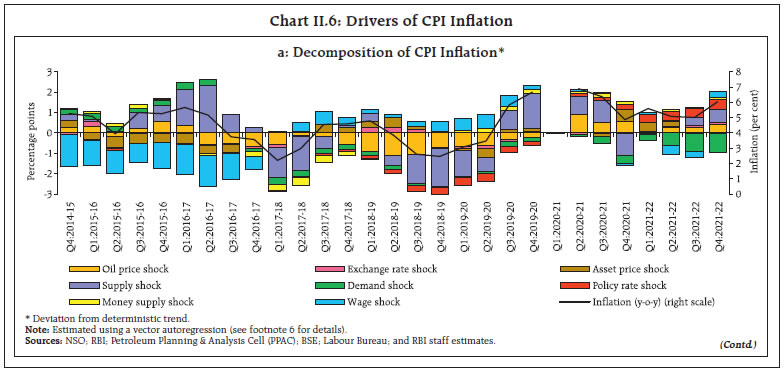

II.1 Consumer Prices The sequential rise in CPI inflation from September 2021 was initially driven up by a pick-up in price momentum, followed by adverse base effects even as price momentum declined.4 In October and November 2021, price momentum increased across food and core categories, but this was couched by favourable base effects in food prices. With the winter setting in, a sharp correction in food prices caused the price momentum to decline in December 2021, but this was more than offset by large unfavourable base effects, resulting in headline inflation hardening by 75 basis points. In January 2022, the decline in food price momentum deepened, but adverse base effects pushed up headline inflation to 6.0 per cent. In February, the CPI headline price momentum turned positive on price pressures from fuel and core categories even though the food price momentum remained negative (Chart II.3). The distribution of CPI inflation during the financial year reveals a high dispersion of inflation rates in the CPI basket, with a considerable positive skew co-existing with a sharp rise in volatility. The large positive skew reflected outliers – oils and fats, fuel and transport – which registered inflation in double digits. The increase in volatility reflected surges and sharp deflation in vegetables prices (Chart II.4). Diffusion indices increased sharply during January-February 2022 across goods and services, indicating a broadening of price pressures (Chart II.5).5 II.2 Drivers of Inflation A historical decomposition of inflation using vector autoregression (VAR) estimates6, to ascertain the various macro-factors that drove inflation dynamics, indicate that the inflationary pressures in H2:2021-22 can be attributed mainly to adverse cost-push factors, coming from supply-side shocks in food and fuel prices, even as weak aggregate demand conditions continued to exert downward pressure on inflation (Chart II.6a).

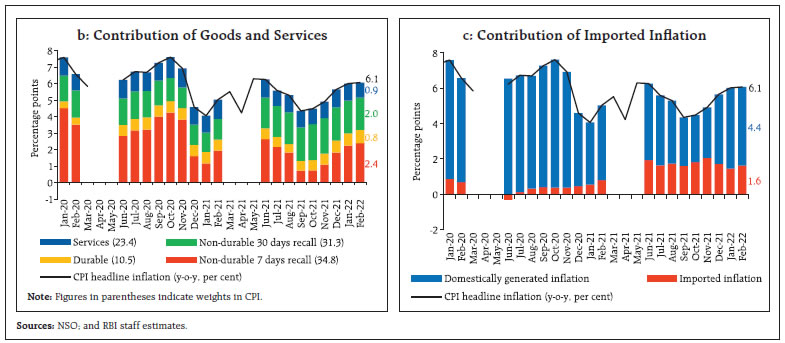

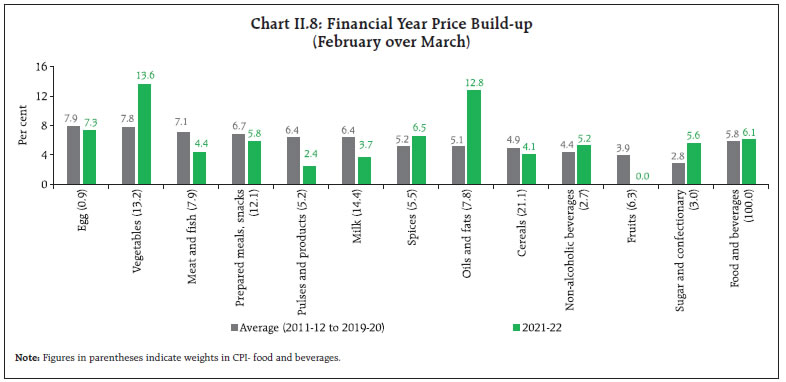

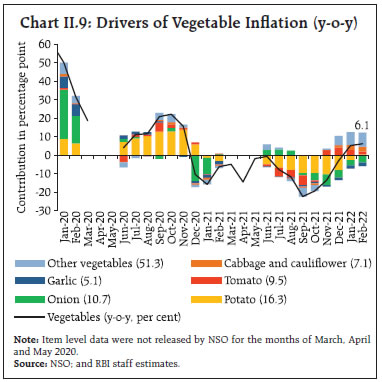

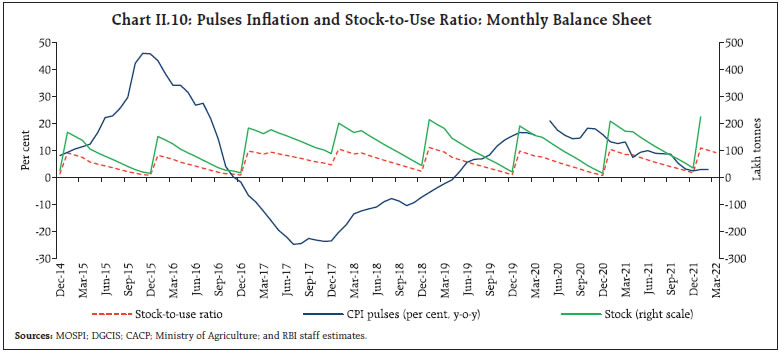

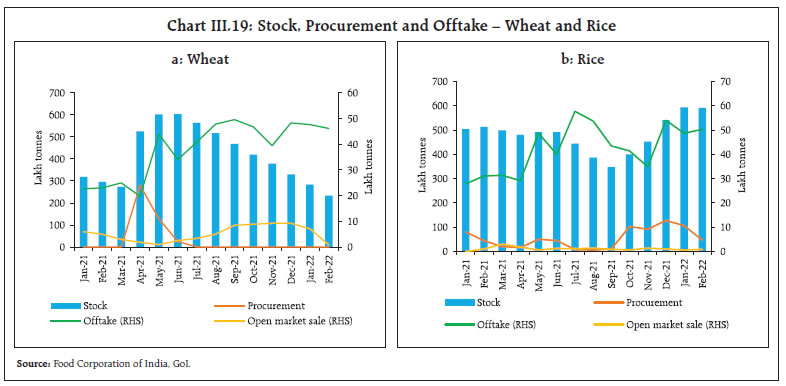

The pick-up in inflation since September 2021 was driven largely by goods inflation, particularly perishables such as vegetables (non-durable goods with a 7-day recall7). The contribution of semi-perishable goods (non-durable goods with a 30-day recall) edged up till October, but declined thereafter, reflecting primarily the movement in petroleum products inflation (Chart II.6b). Durable goods inflation has transmitted heightened cost-push pressures in the manufacturing sector.   The increase in international prices of precious metals, edible oil and petroleum products led to an increase in the contribution of imported components to headline inflation – from 1.8 percentage points (or 40.4 per cent) in October to 2.1 percentage points (41.9 per cent) in November 2021. The decline in international commodity prices in December contributed to lower imported inflation. The cut in central excise duties on petrol and diesel during November, and the series of cuts in edible oils import duties helped in containing the contribution of domestically generated inflation pressures (Chart II.6c). Food Food and beverages (weight of 45.9 per cent in the CPI basket) inflation rose steadily between September 2021 and February 2022. The food price build-up in 2021-22 (up to February) was higher than historical patterns, driven by vegetable and edible oil prices even as protein-based products (milk, egg, meat and fish, and pulses), cereals, fruits and prepared meals experienced lower food price build-ups (Chart II.7a and b). In case of edible oil prices, however, the price declines during November 2021 to January 2022 have not proved sufficient to meaningfully offset the sustained price increases seen in the earlier part of the year, resulting in the price build-up remaining much above historical averages (Chart II.8). Prices of cereals (weight of 9.7 per cent in headline CPI and 21.1 per cent in the CPI food and beverages group), on a year-on-year basis, emerged out of eight months of deflation in October 2021 and reached 4.0 per cent in February 2022. Within cereals, wheat prices have increased sharply since September on higher exports (336.8 per cent y-o-y increase during April 2021-January 2022) and larger procurement. The increase in production (1.6 per cent as per 2021-22 second advance estimate (AE) over 2020-21 final estimates (FE), ample buffer stocks (1.5 times the buffer norms as on March 16, 2022) and free distribution under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) helped contain inflation. In the case of rice, prices remained relatively stable, as the pick-up in exports (by 28.2 per cent y-o-y during April 2021-January 2022) was supported by higher production (2.9 per cent as per 2021-22 2nd AE over 2020-21) and buffer stocks (7.5 times the norm).  Vegetables prices (weight of 6.0 per cent in headline CPI and 13.2 per cent in the CPI food and beverages group) were in deflation under the weight of large favourable base effects during September-December 2021, despite price pressures due to excess rain induced crop damage. Vegetables prices, however, started receding from December, but adverse base effects drove up inflation in this category to 6.1 per cent in February 2022 (Chart II.9). Among the inflation-sensitive vegetables, onion prices hardened during October-November 2021 on account of damages to the stored rabi crop in Maharashtra and Gujarat from cyclone Tauktae in May 2021, followed by damages to kharif crops due to heavy rains in major producing states. Subsequently, prices softened as a result of effective supply side interventions – 2.1 lakh tonnes of onion were released under the price stabilisation fund (PSF) scheme and exports were reduced ((-) 8.5 per cent y-o-y during April 2021-January 2022). Potato prices also escalated during October-November 2021 on account of unseasonal rains. Fresh crop arrivals and ample stocks in cold storages have, however, kept price pressures subdued in subsequent months. Tomato prices also picked up sharply during the same period due to delay in arrivals on account of erratic rains in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh, coupled with supply shortages because of heavy rains in major producing states — Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka.

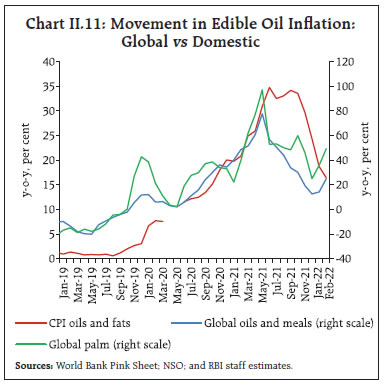

Inflation in prices of fruits (weight of 2.9 per cent in the headline CPI and 6.3 per cent within the food and beverages group) moderated from a three-year high of 11.8 per cent in May 2021 to 2.3 per cent in February 2022, owing to decline in prices of bananas and apples, with apple production higher by 7.1 per cent in 2021-22 (1st AE) over 2020-21 (FE). The record production of pulses during 2021-22 at 269.6 lakh tonnes (2nd AE) has significantly augmented availability. The higher stock-to-use (STU) ratio at end-March 2022 over last March is reflective of improved supply conditions (Chart II.10). Supply-side measures such as moving imports of tur, urad and moong from restricted to ‘free category’ from May 15, 2021; removing import duty on masur and reducing Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess (AIDC) to 10 per cent from July 27, 2021; releasing masur from buffer stocks at discounted price; higher imports of pulses (1.9 per cent y-o-y during April 2021-January 2022); and open market intervention by the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) helped to keep pulses price inflation (weight of 2.4 per cent in the CPI and 5.2 per cent in the food and beverages group) on a moderating trajectory since September 2021.  As regards to animal-based protein items, prices declined in the case of meat and fish (weight of 3.6 per cent in the CPI and 7.9 per cent within the food and beverages group) largely during September 2021-January 2022, primarily reflecting easing feed costs with the import of 12 lakh tonnes of genetically modified soya meal and gradual normalisation of supplies. Prices increased in February 2022 due to winter demand. In the case of eggs, price pressures set in during November 2021-January 2022 and eased in February in accordance with the usual seasonal pattern. Inflation in milk and products gradually increased to 4.1 per cent in January 2022, before easing to 3.8 per cent in February 2022 on favourable base effects, due to successive upward revisions in milk prices by milk co-operatives in various states after July 2021, following the increase in prices by around ₹2 per litre by major milk co-operatives like Amul and Mother Dairy. Inflation in prices of oils and fats (weight of 3.6 per cent in the CPI and 7.8 per cent within the food and beverages group) continued to rule in double digits since September 2021 albeit with some moderation on the back of supply-side measures and improved prospects for the rabi crop (rabi oilseeds production was higher by 9.1 per cent as per 2nd AE 2021-22) and moderation in international prices of edible oils (Chart II.11). Some important steps taken to ebb price pressures include imposition of stock limits on edible oils and oilseeds pan India, except for six states (Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Telangana and Uttar Pradesh which imposed their own stock limit order) up to June 30, 2022, and significant reduction in import duty in a gradual manner on palm oil, soyabean oil and sunflower oil. Overall, during the period from October 2021 to February 2022, the effective import duty on the three major imported crude edible oils, viz. palm oil, soyabean oil and sunflower oil, was reduced by 19.25 percentage points to a weighted average of 5.5 per cent. During the same period, the effective import duty of RBD palmolein/ RBD palm oil and refined soyabean/ sunflower oil was also reduced by 22.0 percentage points and 16.5 percentage points, respectively, to 13.75 and 19.25 per cent.  Prices of sugar and confectionery (weight of 1.4 per cent in the CPI and 3.0 per cent in the food and beverages group) emerged out of deflation in September 2021 and averaged 5.2 per cent during September 2021 to February 2022, reflecting, higher exports (54.0 per cent y-o-y in April 2021-January 2022, as per DGCIS), the government’s enhanced target of 10 per cent ethanol blending (against 8.5 per cent earlier) and adverse base effects. Prices declined during December 2021-February 2022 due to the onset of domestic production season, coupled with the decision to extend the sale of unsold sugar quota of previous months in November 2021 and January 2022 and moderation in international sugar prices since December 2021. Among other food items, prices hardened in the case of prepared meals, driven by cooked meals and cooked snacks as increased input costs fed through. For non-alcoholic beverages, tea prices rose on lower production and higher consumption. In the case of spices, price pressures emerged since December 2021 on account of production shortfalls. Retail Margins The retail price margin8, defined as the difference of retail and wholesale prices, for cereals, pulses, and edible oil remained elevated till March 2022. On the other hand, margins in the case of vegetables softened, particularly for tomatoes, as per the seasonal pattern, but remained higher than in the past (Chart II.12). Impact of the Russia Ukraine War on Domestic Food Prices The Russia-Ukraine conflict poses considerable upside risks to prices of key food items. Even as adverse spillovers through direct trade remain limited (Chapter III), the Russia-Ukraine war may have a significant impact on inflation through the global commodity markets channel (Chapter V). In the case of edible oils, the loss of supplies of sunflower oil from Black Sea region is likely to keep domestic prices under pressure. The Black Sea region accounts for around 75 per cent of global production of sunflower oil and is a key supplier to India. The situation is being compounded by the tightness in global soybean market and the increase in export levies as well as export restrictions by key producing countries. On the other hand, the significant increase in domestic mustard production is likely to provide some cushion to the price pressures. Russia and Ukraine account for about a quarter of global wheat exports. Since the beginning of the Ukraine war, international wheat prices have soared. India is not an importer of wheat, but exports from India have picked up sharply in the current year (336.8 per cent y-o-y during April 2021-January 2022). Therefore, international prices could set a floor for domestic wheat prices through the export channel, even if domestic prices do not move in sync with global prices. However, ample stocks along with a bumper production may help to keep any price increase range bound. Fuel Fuel inflation surged from 12.9 per cent in August 2021 to 13.6 per cent in September and further to 14.3 per cent in October, reaching new peaks in these three consecutive months (Chart II.13a). The key driver of this pick-up was the sharp rise in international prices of kerosene and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and its transmission to domestic prices (Chart II.13b and c). From November, fuel inflation moderated sequentially to 8.7 per cent in February 2022, enabled by the abrupt slip in electricity prices to deflation since November and LPG prices remaining unchanged since October 2021. Kerosene prices moderated during December 2021-January 2022, reflecting the fall in international prices. In February, as international prices picked up and pass-through became evident, domestic prices also registered a sharp increase. LPG prices were also increased by ₹50 per cylinder on March 22, 2022. Core Core inflation, i.e., CPI inflation excluding food and fuel, remained elevated at around 6 per cent in 2021-22 as relentless cost-push pressures impinged on goods and services selling prices (Table II.1). | Table II.1: Exclusion-based Measures of Inflation (y-o-y) | | Period | Exclusion based measures | | CPI excluding food and fuel (47.3) | CPI excluding food fuel petrol diesel (45.0) | CPI excluding food fuel petrol diesel gold silver (43.8) | | Jun-19 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | | Sep-19 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 4.5 | | Dec-19 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.3 | | Mar-20 | 3.9 | | | | Jun-20 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 4.6 | | Sep-20 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.5 | | Dec-20 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 4.7 | | Jan-21 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 4.7 | | Feb-21 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.1 | | Mar-21 | 5.9 | | | | Apr-21 | 5.3 | | | | May-21 | 6.6 | | | | Jun-21 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 5.4 | | Jul-21 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 5.3 | | Aug-21 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 5.6 | | Sep-21 | 5.9 | 5.2 | 5.6 | | Oct-21 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 5.4 | | Nov-21 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 5.7 | | Dec-21 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 5.9 | | Jan-22 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 5.8 | | Feb-22 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.7 | Note: (1) Figures in parentheses indicate weights in CPI.

(2) Derived as residual from headline CPI.

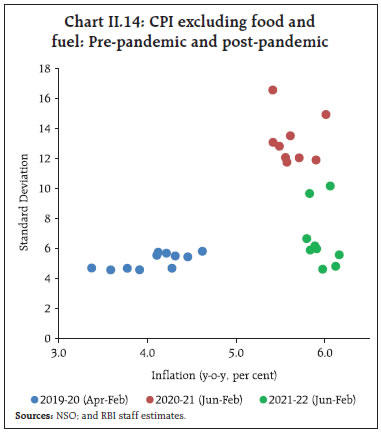

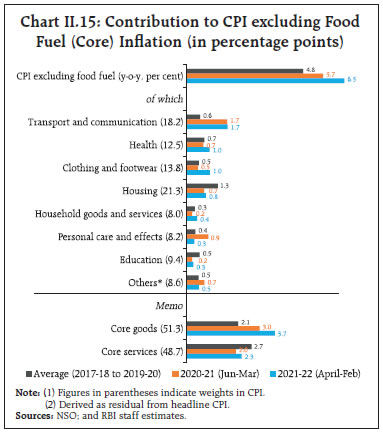

Sources: NSO; and RBI staff estimates. | Core inflation was sticky and higher than in the pre-COVID period during 2021-22, with elevated core price pressures coexisting with significantly lower volatility than a year ago (Chart II.14). A comparative assessment of the drivers of core inflation in 2021-22 (April-February) vis-à-vis pre-COVID years (i.e., 2017-18 to 2019-20) and 2020-21 (June 2020 to March 20219) shows that core goods as well as core services inflation were higher in 2021-22. Also, inflation rates across core sub-groups, barring housing and education, were higher than in 2020-21. Transport and communication, in addition to health, remained the key drivers, as in 2020-21. While the contribution of clothing and footwear to overall core inflation edged up sharply in 2021-22, the contribution of personal care and effects declined (Chart II.15).

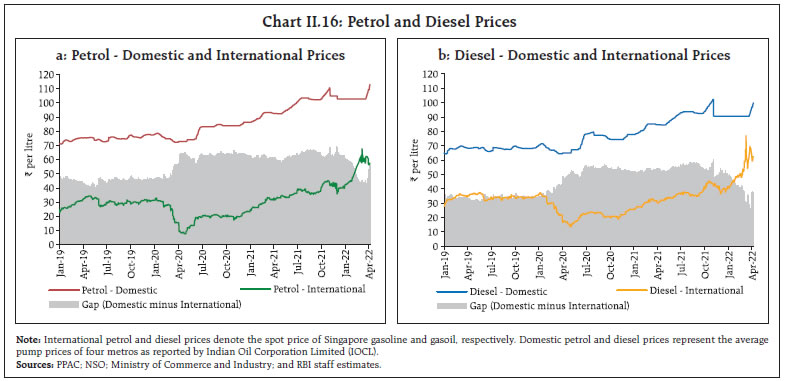

A key source of core inflationary pressures during September 2021 to February 2022 has been petrol and diesel. Some softening since November was facilitated by the cut in central excise duties on petrol by ₹5 per litre and on diesel by ₹10 per litre on November 4, 2021 along with a reduction in State VATs in petrol and/or diesel by 28 States/ UTs during November-December 2021. As a result, pump prices scaled down from historic highs recorded during November 1-3, 2021. However, Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) after adjusting for the tax cuts kept the retail selling prices unchanged till the third week of March, even as international crude oil prices exhibited two-way movement – a moderation during December 2021 before reversing course since early January 2022 and a precipitous rise from end-February on Russia-Ukraine conflict (Chart II.16). Since March 22, with OMCs commencing the pass-through of high international crude oil prices to domestic pump prices, petrol and diesel retail selling prices have registered a cumulative increase of around ₹10 per litre in 14 revisions so far (till April 6, 2022). Various measures of core inflation have remained elevated in a range of 5.0-6.2 per cent during September 2021-February 2022 (Table II.1). Decomposing CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol, diesel, gold and silver into its goods and services components points to contrasting movements. Inflation in the goods component (with a weight of 20.7 per cent in the headline CPI) increased consecutively from August 2020, reaching 7.0 per cent in November 2021 and plateauing thereafter. This was driven primarily by clothing and footwear – readymade garments and uniforms; health care goods —medicines, household goods and personal care items and toiletries (Chart II.17a). On the other hand, services inflation (with a weight of 23.0 per cent in the headline CPI) which was at 4.5 per cent in August 2021, softened to 4.2 per cent in October before firming up to 4.7 per cent during December 2021-February 2022 (Chart II.17b). The pick-up in services inflation was on account of the transport and communication sub-group, coming from an increase in mobile telephone charges during December 2021-January 2022. The contribution of household services (which includes domestic servant/cook/sweeper charges, monthly maintenance charges) and recreation and amusement services (cinema; club; hotel lodging charges) also increased during this period. The contribution of services to core inflation continued to remain lower, on an average, than what was seen in the pre-pandemic period, particularly on account of relatively subdued growth in house rentals (Chart II.15).

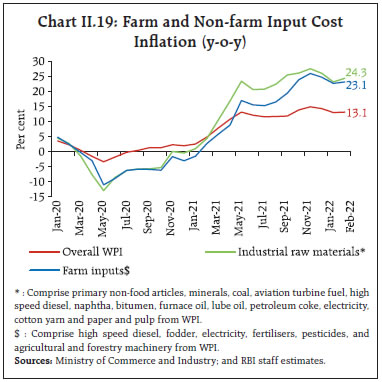

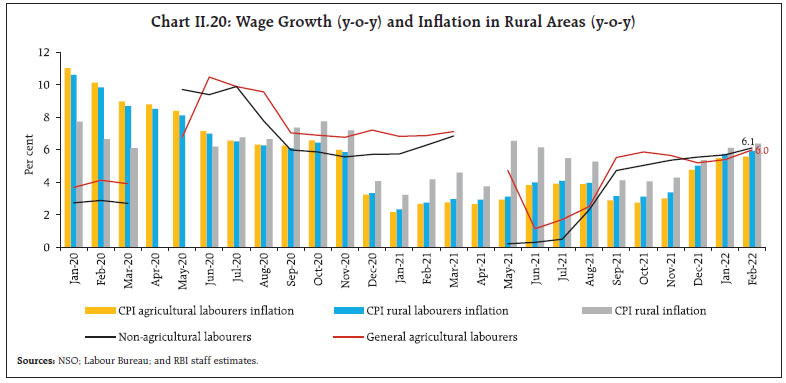

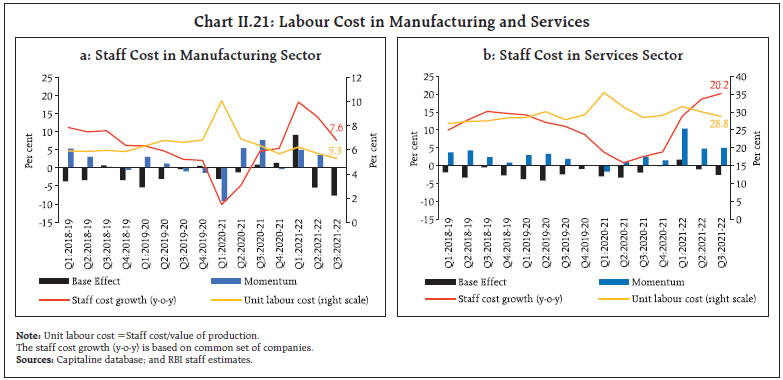

In order to filter noise out of CPI inflation, two common approaches are (i) excluding a fixed set of components from the CPI basket that display volatile price movements, and (ii) excluding different components each month if they are located in the tails of the inflation distribution. The exclusion-based measures show high and persistent inflationary pressures during September 2021-February 2022 (Table II.1). Inflation measured by trimmed means also edged up during this period (Table II.2). | Table II.2: Trimmed Mean Measures of Inflation (y-o-y) | | Month | 5% trimmed | 10% trimmed | 25% trimmed | Weighted Median | | Jun-19 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.8 | | Sep-19 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.8 | | Dec-19 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.0 | | Mar-20 | | | | | | Jun-20 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 4.9 | | Sep-20 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 5.1 | | Dec-20 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 4.0 | | Jan-21 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 3.6 | | Feb-21 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 3.7 | | Mar-21 | | | | | | Apr-21 | | | | | | May-21 | | | | | | Jun-21 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.2 | | Jul-21 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.6 | | Aug-21 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 4.3 | | Sep-21 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.3 | | Oct-21 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.6 | | Nov-21 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | | Dec-21 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.7 | | Jan-22 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.1 | | Feb-22 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 5.6 | | Sources: NSO; and RBI staff estimates. | Other Measures of Inflation Inflation measured by sectoral CPIs for agricultural labourers (CPI-AL) and rural labourers (CPI-RL) has persisted below CPI headline inflation for the past 20 months. By February 2022, however, the extent of divergence gradually narrowed. Both food and fuel inflation were generally lower in the CPI-AL and CPI-RL vis-à-vis CPI, resulting in lower inflation prints. Inflation in terms of the CPI for industrial workers (CPI-IW) has moved broadly in line with the headline CPI during September to January 2022. In February 2022, however, there was a substantial divergence on account of lower food inflation in CPI-IW vis-à-vis headline CPI. WPI inflation, which was in double digits since the start of 2021-22, edged up further since September 2021, reaching an all-time high of 14.9 per cent (as per the WPI series, 2011-12=100) in November 2021. A sharp and broad-based surge in price momentum, despite strong favourable base effects, drove the pick-up in WPI inflation. Persistently high WPI core10 inflation, which remained in double digits from May to December 2021, reflected high commodity and input price pressures as well as supply-side disruptions. WPI inflation moderated somewhat to 14.3 per cent and further to 13.0 per cent in December 2021 and January 2022, respectively, before picking up marginally to 13.1 per cent in February 2022. In line with WPI inflation, the deflators for gross value added (GVA) and gross domestic product (GDP) remained elevated between Q1:2021-22 to Q3:2021-22. In H2:2021-22, WPI and CPI inflation have diverged markedly (Chart II.18a). During September 2021 to February 2022, all the major subgroups of WPI, namely, food, fuel and excluding food and fuel (core) remained substantially above the corresponding subgroups in the CPI. Year-on-year growth in prices of petrol and diesel diverged considerably between CPI and WPI (Chart II.18b) as the CPI, which records prices inclusive of taxes, moderated following the reduction in excise duties and State VATs in November-December 2021. Among food sub-groups, fruits and eggs registered higher price increases on a y-o-y basis in the WPI relative to the CPI. In the WPI, vegetable inflation remained elevated whereas in the CPI, prices of vegetables recorded deflation during September-December 2021, before turning up. II.3 Costs Costs, as measured by WPI inflation in industrial raw materials and farm inputs, remained elevated during H2:2021-22 (Chart II.19). Disruptions in global supply chain in the form of logistics bottlenecks, increase in shipping costs, and longer delivery times resulted in input cost pressures. The firming up of global crude oil prices was the main factor that impacted the prices of industrial inputs such as naphtha, aviation turbine fuel, bitumen, petroleum coke and furnace oil. They also contributed to double-digit inflation in high-speed diesel, which in turn drove up farm input price inflation. Other contributory factors comprise fertiliser prices that edged up in sympathy with international prices, and prices of some non-food articles that remained in double digits – raw cotton and oilseeds. Price of electricity – a key input in both industrial and farm inputs – also increased sharply during the period in line with revival in demand. Inflation in industrial raw materials and farm inputs, however, eased during December 2021-January 2022 on account of softer prices of petroleum products but picked up again in February 2022 amidst rising international prices and heightened geopolitical uncertainties.  The ongoing conflict in the Black Sea region and ensuing sanctions have hampered global supply chains and have also sent prices soaring with aluminium and nickel prices rising to highest level in the last decade. Russia is one of the largest producers of aluminium, widely used in transportation and construction industry, and of nickel, mostly used for high grade steel manufacturing and in batteries. Further geopolitical tension in the region is likely to aggravate global chip shortage and could impact prices of vehicles and electronic products. Nominal rural wages for both agricultural and non-agricultural labourers picked up during H2:2021-22, with easing of restrictions/lockdowns imposed by states and restoration in economic activity. However, the wage growth remained soft (Chart II.20). In the organised sector, staff cost growth (y-o-y) for both manufacturing and services picked up in Q1 of 2021-22 but decelerated for manufacturing and remained steady for services in the next two quarters, with softer momentum in Q2 and Q3. Unit labour costs also moderated in Q3:2021-22 owing to the sharp increase in growth in value of production of the listed firms both in manufacturing and services vis-à-vis staff costs during Q2 and Q3:2021-22 (Chart II.21a and b).

Manufacturing firms polled for the purchasing managers’ index (PMI) reported a sustained increase in input prices in March 2022. Also, the PMI services sector reported continued increase in input prices till March 2022 with firm momentum, mainly driven by higher fuel, raw material, chemical, retail, vegetable and transportation costs. However, the pace of output prices for both manufacturing and services sectors so far remained modest as compared to input prices, reflecting restricted pass-through amidst firms’ limited pricing power due to the prevalent slack in the economy (Box II.1). Box II.1: An Analysis of Sensitivity of Output Prices to Input prices Input cost prices have been rising during 2021-22, though its pass-through to output prices has remained muted in view of the continuing slack in demand (Patra, 2022). The gap between input and output prices has remained wide during 2021-22 (Chart II.1.1). In advanced economies like the United States and the Euro area, pricing power of firms has increased significantly against intense pressures from elevated input prices and in the presence of strong demand (Vijlder, 2022). In the Indian context, PMI price indices have significant predictive power about changes in wholesale price inflation (WPI) (Khundrakpam and George, 2013) 11. Granger causality tests using monthly data from January 2011 to February 2022 confirm that PMI input prices do influence output prices and core CPI, a measure of inflation exclusive of volatile components i.e., food and fuel, with no evidence of reverse causality12. To further examine the strength of the relationship, ordinary least squares (OLS) and autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) models are used depending upon the degree of integration of the variables.13 Empirical analysis in an OLS framework suggests pass-through from lagged PMI composite input prices to corresponding output prices, after controlling for future output14 (Table II.1.1a). The pass-through is, however, less than complete, reflecting, inter alia, the role of other demand side factors. Analysis of PMI composite input prices and core CPI inflation along with PMI future output for the period April 2012 to February 2022 in an ARDL model of co-integration, which allows for use of variables of different degrees of integration, confirms the existence of a long run co-integrating relationship (Table II.1.1b). The long run pass-through coefficient from PMI input prices to core CPI at 0.11 is modest. | Table II.1.1: Empirical Results: Input to Output prices | | a. OLS: Composite PMI Input to Output prices | b. ARDL: Composite PMI Input prices to Core CPI | | Dependent Variable: Output prices | Bounds test for Co-integration@ | F-statistic | 3.50* | | Constant | 31.213***

(0.00) | Note: “Ho: No Co-integration”; “H1: There is long run co-integrated relationship”;

@: Future output as a control; Conventional significance based on F-statistics as extracted from Narayan (2005). | | Input Prices (lagged) | 0.233***

(0.00) | | Future Output | 0.130***

(0.00) | | Dum_Apr20 | -9.563***

(0.00) | Long run estimation

(Dependent variable: Core CPI) | | Adjusted R-square | 0.74 | PMI input prices | 0.108***

(0.00) | Note: ***, ** and * indicate the rejection of the null hypothesis at 1, 5 and 10 per cent levels of significance. Figures in parenthesis are p-values. The ARDL models are chosen based on automatic selection by AIC criteria. OLS model is with four lags.

The results are estimated for period: April 2012-Febraury 2022.

Source: RBI staff estimates. | References: Khundrakpam, J. K., & George, A. T., (2013), “An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between WPI and PMI-Manufacturing Price Indices in India”, Reserve Bank of India, WPS (DEPR):06 Patra, M.D. (2022), “Taper 2022: Touchdown in Turbulence” speech at the IMC Chamber of Commerce and Industry”, March. Vijlder, W., (2022), “Companies’ Pricing Power and the Inflation Outlook”, BNP Paribas. | The salary outgo for the manufacturing, services and infrastructure firms polled in Reserve Bank’s enterprise surveys15 reported an increase in Q3:2021-22. For manufacturing firms, the pace of increase moderated in Q4:2021-22 and expected to pick up again in Q1:2022-23, but in the case of services and infrastructure firms, it is expected to moderate in Q1:2022-23. Input cost pressures remained elevated for manufacturing, services and infrastructure firms during Q3 and Q4:2021-22. During Q1:2022-23, manufacturing input costs are expected to remain elevated while some moderation in pace of increase may occur for services and infrastructure firms. Manufacturing firms may charge higher selling prices in Q1:2022-23, vis-à-vis their services and infrastructure sector counterparts (Chart II.22). One year ahead business inflation expectations16 polled by the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, rose sequentially, crossing 6 per cent in February 2022. The businesses polled in the survey reported further heightening of cost pressures, which along with weak demand conditions impacted profit margins of the sampled firms.  II.4 Conclusion Recent geopolitical events have accentuated upside risks to inflation. Global supply shocks are still unfolding and their ambit across commodities is widening. Input costs, including energy costs, for various manufacturing goods and services are also likely to go up. The impact of recent events will also be conditioned by the outlook for aggregate demand going forward. Persistent commodity price pressures along with the resurgence of global supply chain and logistics disruptions pose risk of their pass-through to domestic inflation. Though the pass-through so far has been limited due to weak demand conditions, going forward it may need to be monitored carefully. The headroom available for supply side measures remain critical to limit the extent of transmission of adverse cost conditions onto retail prices of goods and services. _______________________________________________________________________________________________

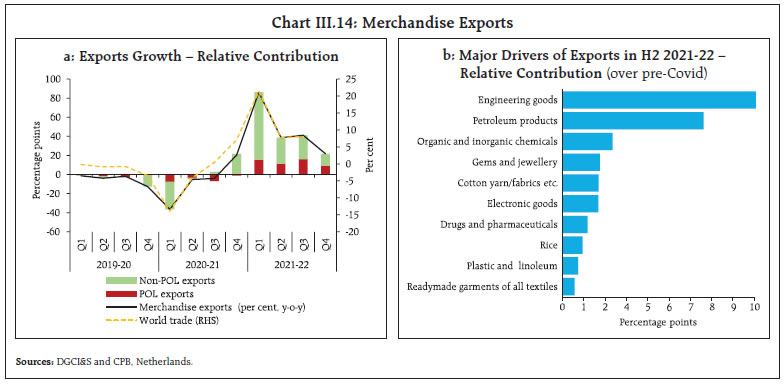

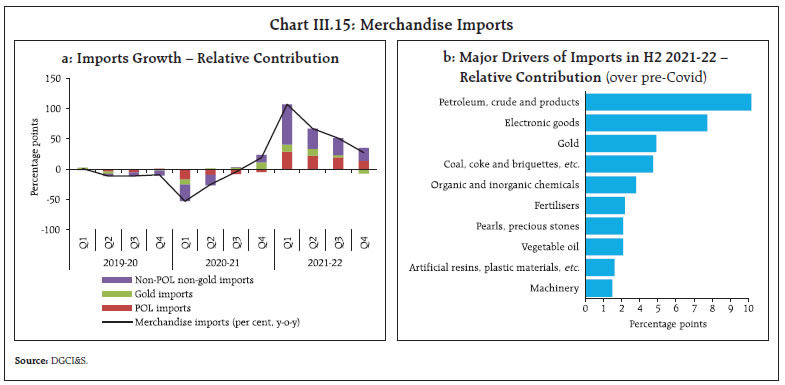

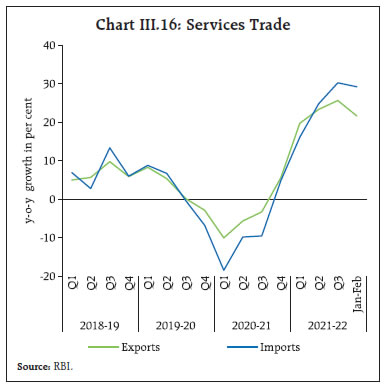

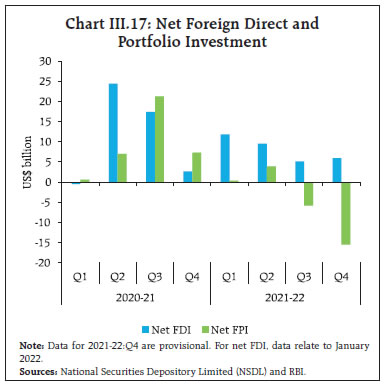

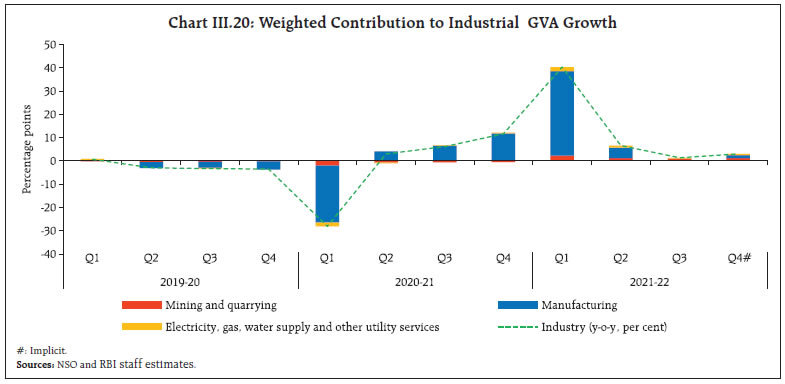

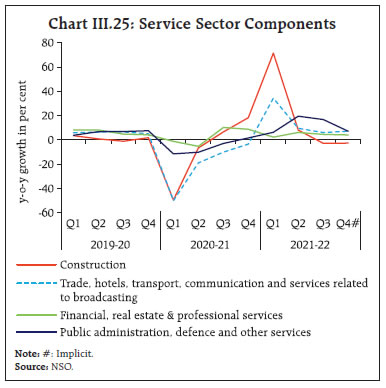

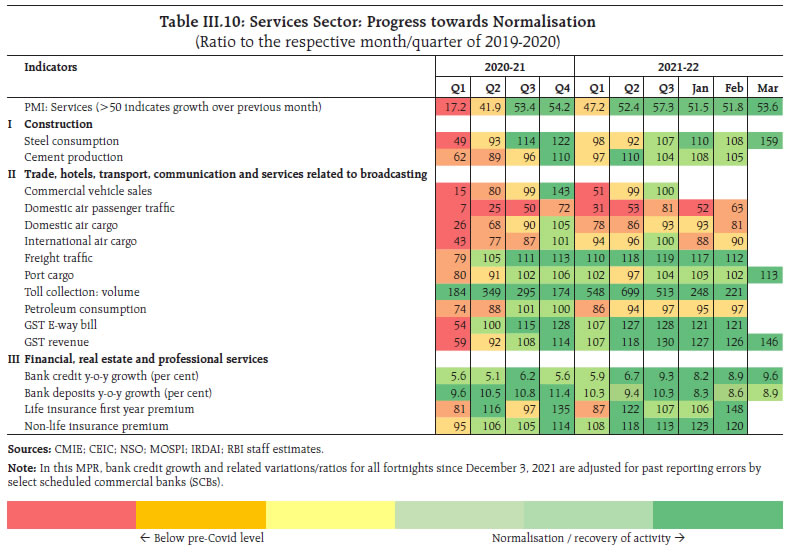

III. Demand and Output The recovery in aggregate demand lost some momentum in H2:2021-22 with the emergence of the Omicron variant. External demand remained buoyant. The intensification of geopolitical tensions, the surge in global oil and commodity prices to multi-year highs and intense financial market volatility pose significant downside risks to global economic activity and could have spillovers on domestic growth prospects. The recovery in aggregate demand that had resumed with the ebbing of the second wave of the pandemic lost some momentum in H2:2021-22 with the emergence of the Omicron variant. Although more transmissible, the third wave turned out to be less severe and short-lived relative to the second wave (Chart III.1). As a result, GDP in H2 is estimated to be higher by 6.8 per cent than the corresponding pre-pandemic levels, with the demand for contact-intensive activities impacted in December 2021-January 2022 and the informal sector and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) still lagging. External demand, on the other hand, remained buoyant, with merchandise exports clocking double-digit growth for the thirteenth month in a row in March 2022. On the aggregate supply side, manufacturing weakened in the face of headwinds from persisting global supply bottlenecks and muted discretionary consumption and investment spending domestically. In contrast, agriculture and allied activities remained buoyant on the back of a record kharif production and expansion in sowing acreage in the rabi season relative to a year ago.

| Table III.1: Real GDP Growth | | (y-o-y, per cent) | | Item | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | Weighted Contribution* | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | | (FRE) | (SAE) | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4# | | Private final consumption expenditure | -6.0 | 7.6 | -3.4 | 4.4 | -23.7 | -8.3 | 0.6 | 6.5 | 14.2 | 10.2 | 7.0 | 1.5 | | | | (1.2) | | | | | | | (-13.0) | (1.1) | (7.6) | (8.1) | | Government final consumption expenditure | 3.6 | 4.8 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 13.6 | -22.9 | -0.3 | 29.0 | -4.4 | 9.3 | 3.4 | 11.7 | | | | (8.6) | | | | | | | (8.6) | (-15.8) | (3.1) | (44.0) | | Gross fixed capital formation | -10.4 | 14.6 | -3.3 | 4.4 | -45.3 | -4.5 | -0.6 | 10.1 | 62.5 | 14.6 | 2.0 | 1.3 | | | | (2.6) | | | | | | | (-11.2) | (9.5) | (1.4) | (11.5) | | Exports | -9.2 | 21.1 | -1.8 | 4.0 | -25.5 | -6.4 | -8.6 | 3.7 | 40.4 | 20.5 | 20.9 | 7.8 | | | | (9.9) | | | | | | | (4.6) | (12.7) | (10.5) | (11.8) | | Imports | -13.8 | 29.9 | -3.2 | 6.3 | -41.1 | -17.9 | -5.2 | 11.7 | 60.7 | 40.7 | 32.6 | 1.3 | | | | (11.9) | | | | | | | (-5.3) | (15.5) | (25.8) | (13.2) | | GDP at market prices | -6.6 | 8.9 | -6.6 | 8.9 | -23.8 | -6.6 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 20.3 | 8.5 | 5.4 | 4.8 | | | | (1.8) | | | | | | | (-8.3) | (1.3) | (6.2) | (7.4) | Note: *: Component-wise contributions to growth do not add up to GDP growth because change in stocks, valuables and discrepancies are not included.

Figures in parentheses are growth rates over 2019-20. FRE: First revised estimates; SAE: Second advance estimates. #: Implicit.

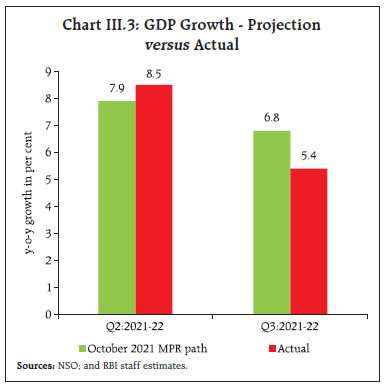

Source: National Statistical Office (NSO). | III.1 Aggregate Demand Aggregate demand, measured by real gross domestic product (GDP), decelerated to 5.4 per cent year-on-year (y-o-y) in Q3:2021-22 (Table III.1 and Chart III.2a). All its major constituents surpassed their pre-pandemic levels, as recovery gained traction. With the fast ebbing of the third wave, the demand for contact-intensive services also recovered in February-March 2022. For the financial year 2021-22, real GDP is estimated to have risen by 8.9 per cent, taking its level 1.8 per cent above that recorded in 2019-20. Private consumption and government expenditure were the key drivers of aggregate demand in H2 (Chart III.2b). The negative contribution of net exports to aggregate demand moderated. GDP Projections versus Actual Outcomes The October 2021 Monetary Policy Report (MPR) had projected real GDP growth at 7.9 per cent for Q2:2021-22, 6.8 per cent for Q3 and 6.1 per cent for Q4. Actual growth in Q2 overshot the projection by 60 basis points (bps) while it undershot the projection by 140 bps in Q3 (Chart III.3). These upside and downside surprises stemmed mainly from a stronger than expected release of pent-up demand and a pick-up in investment on the back of government capex in Q2, followed by a loss of momentum in Q3. Data for Q4:2021-22 are scheduled for release by the NSO on May 31, 2022. III.1.1 Private Final Consumption Expenditure Private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) – the mainstay of aggregate demand – regained some traction, but its share in overall GDP dropped to 56.6 per cent in 2021-22 from 57.3 per cent in the previous year, weighed down by incomplete recovery in the labour force participation rate, the third wave and weak consumer confidence (Box III.1). The sluggish recovery in the informal sector and among MSMEs also restrained private consumption. Expanding vaccination coverage, and relaxation of restrictions on mobility and activity enabled a recovery in demand for contact-intensive services such as air travel, hotels and restaurants, recreation and culture in February-March 2022.

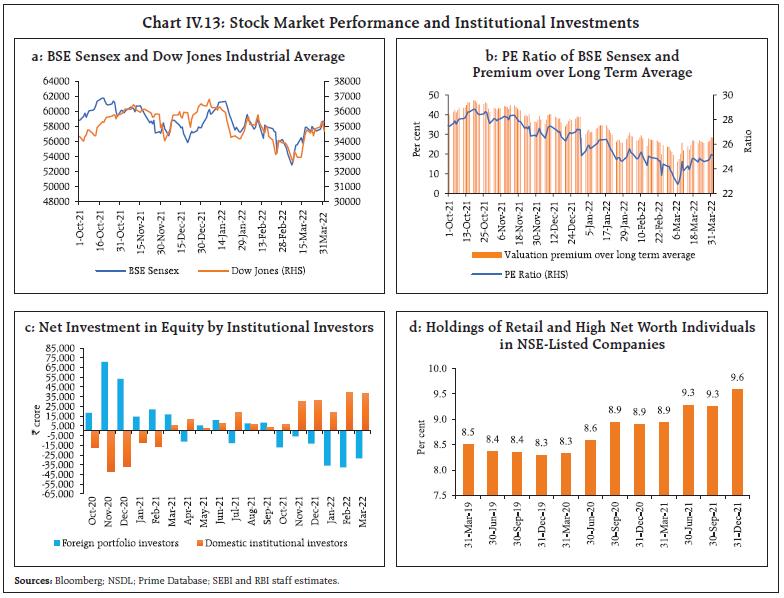

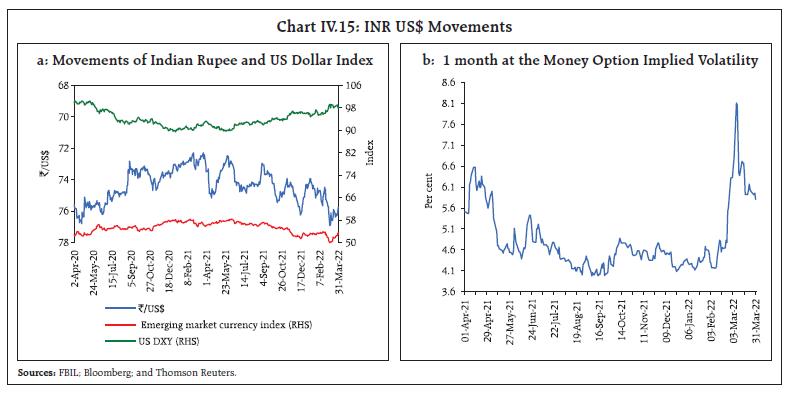

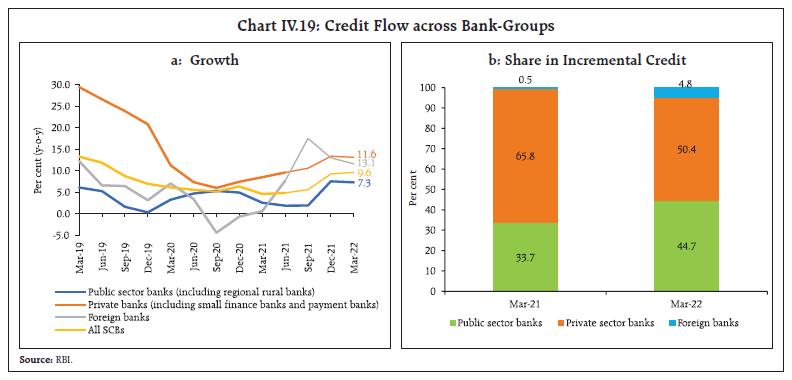

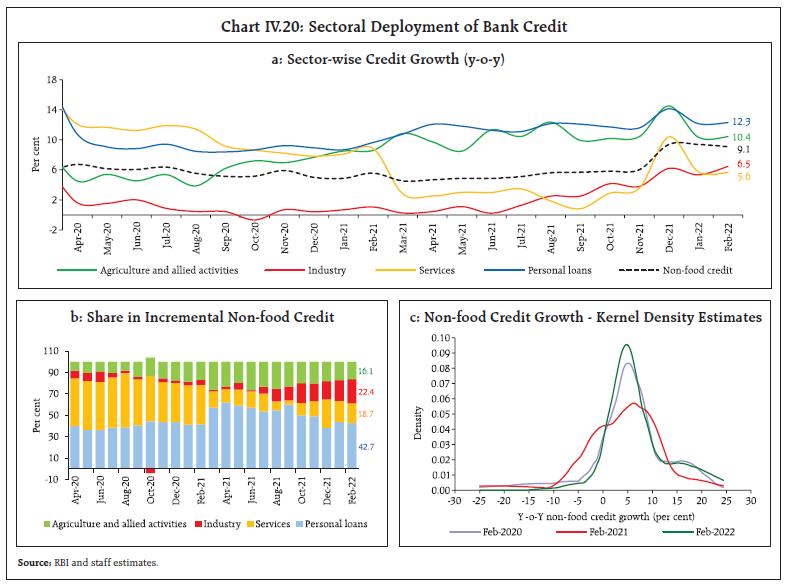

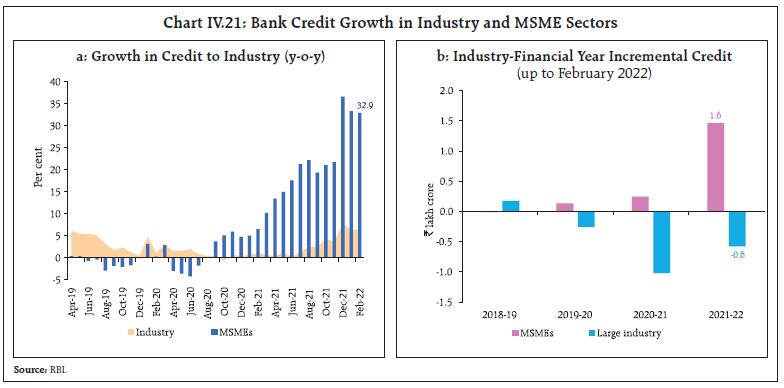

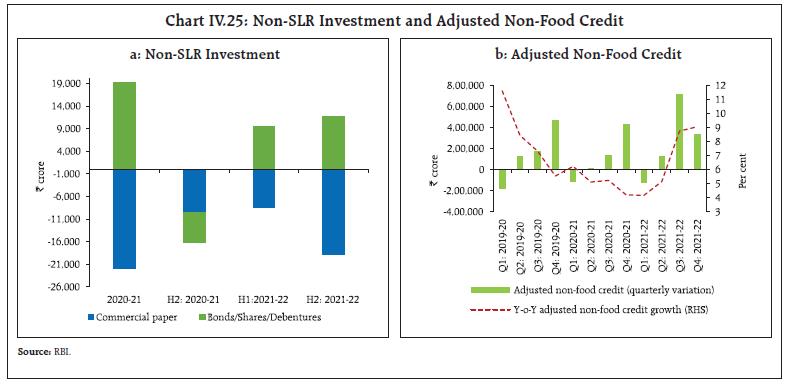

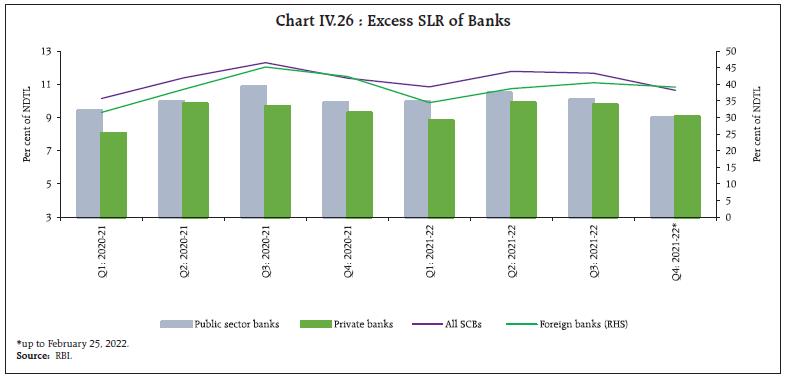

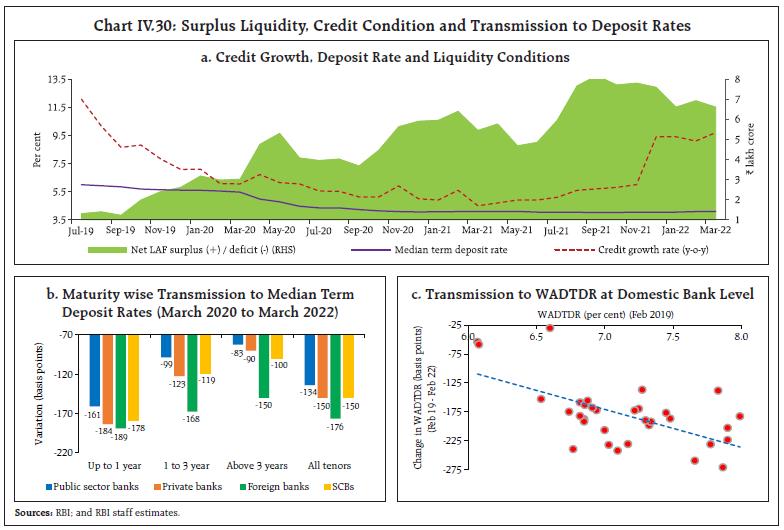

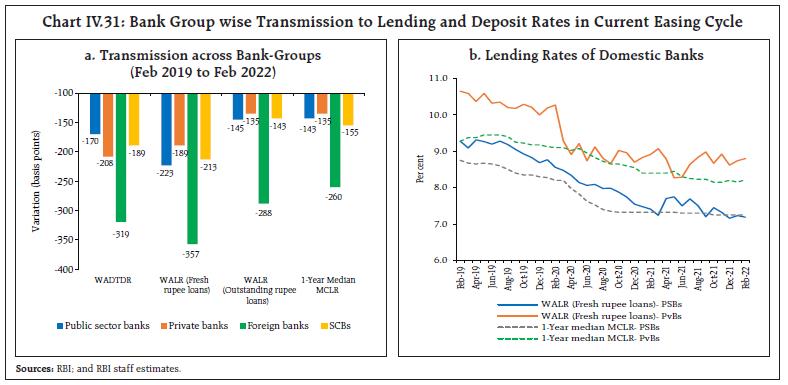

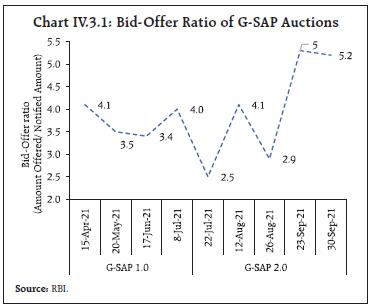

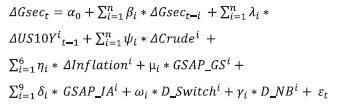

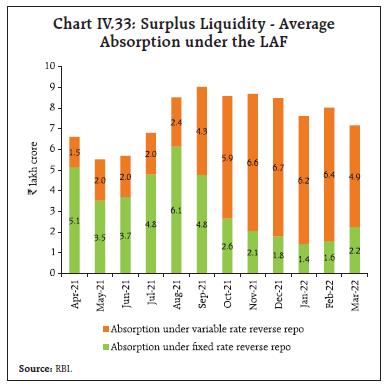

Box III.1: Drivers of Private Consumption Income, wealth, inflation, interest rate and consumer confidence are potential determinants of private consumption (Singh, 2012; Vihriälä, 2017; Wong, 2017; Dossche, et. al., 2018). According to unit root tests, private consumption and income (real GDP) are non-stationary1. For the pre-pandemic period, i.e., 2004-19, quarterly data indicate a long-run co-integrating relationship between real private consumption and income2. The short-run error-correction dynamics points to the role of the cyclical factors – lower interest rates and lower inflation support consumption demand, attesting to a role of accommodative monetary policy. Going ahead, given the long-run relationship, consumption can be expected to recover with rising incomes. References: Dossche, M., M Forsells, L Rossi, G Stoevsky (2018), “Private Consumption and its Drivers in the Current Economic Expansion”, Economic Bulletin, European Central Bank. Singh, Bhupal (2012), “How Important is the Stock Market Wealth Effect on Consumption in India?”, Empirical Economics, Vol. 42, pp. 915-927. Vihriälä, E. (2017), “Household Consumption in Japan- Role of Income and Asset Developments”, IMF Working Paper WP/17/23. Wong, M. (2017), “Revisiting the Wealth Effect on Consumption in New Zealand”, Reserve Bank of New Zealand Analytical Note, AN2017/03. | Urban consumption was lifted by a recuperation in domestic air passenger traffic, especially during February-March, and a moderation in the contraction of passenger vehicle sales that had been hit by shortages in respect of semi-conductor chips (Chart III.4). Consumer durables production, on the other hand, fell in Q3 and January due to subdued discretionary spending. As regards rural demand, sales of two-wheelers recorded y-o-y contraction during H2, indicative of pressures on discretionary household spending and slow recovery in the informal sector. Tractor sales were lower during November-February partly due to protracted and heavy precipitation in some areas. Fertiliser sales also remained lower during January- February, reflecting inventory de-stocking and lower imports amidst rising international prices. Consumer non-durables production, on the other hand, rebounded in January 2022 (Chart III.5). Consumer pyramids household survey data of the CMIE show that the labour force participation rate (LFPR) fell from 40.9 per cent in December to 39.5 per cent in March 2022; the unemployment rate, however, dropped from 7.9 per cent to 7.6 per cent over the same period and remained lower than the levels recorded during the first and second waves (Chart III.6a). Employment conditions improved in Q3 and January in the organised sector (Chart III.6b). III.1.2 Gross Fixed Capital Formation Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) expanded by 14.6 per cent in 2021-22 on the back of a favourable base (-10.4 per cent in 2020-21) and its share in GDP rose marginally to 32.0 per cent as against 31.8 per cent in 2019-20. In H2, however, investment activity weakened, driven down by sluggish construction activity (reflected in steel consumption and cement production) due to unseasonal rains, rising input costs and shortage of manpower (Chart III.7). The domestic production of capital goods slipped into contraction in Q3:2021-22 and January 2022, weighing on overall investment activity, even as imports of capital goods expanded during Q3 and Q4.