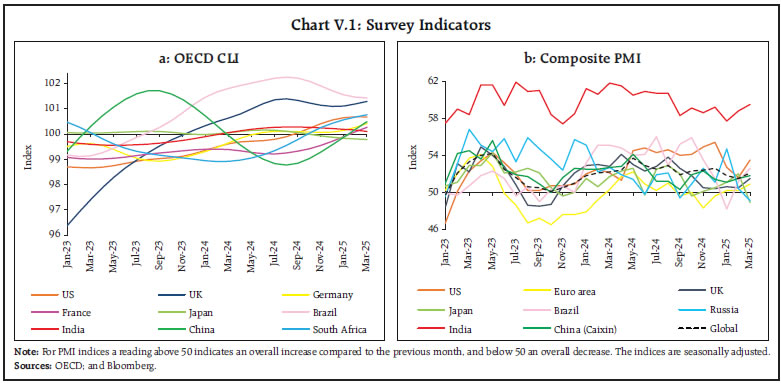

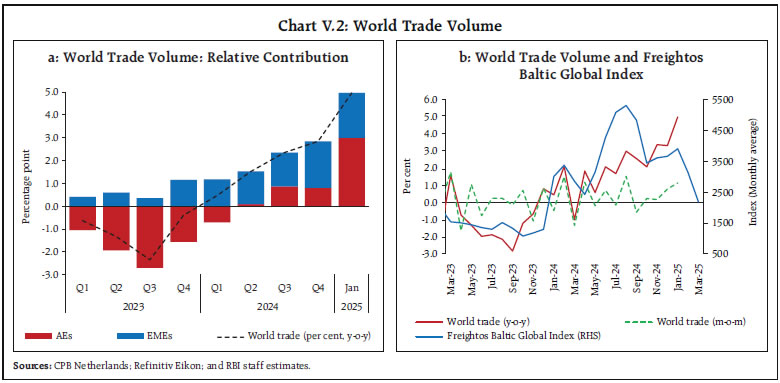

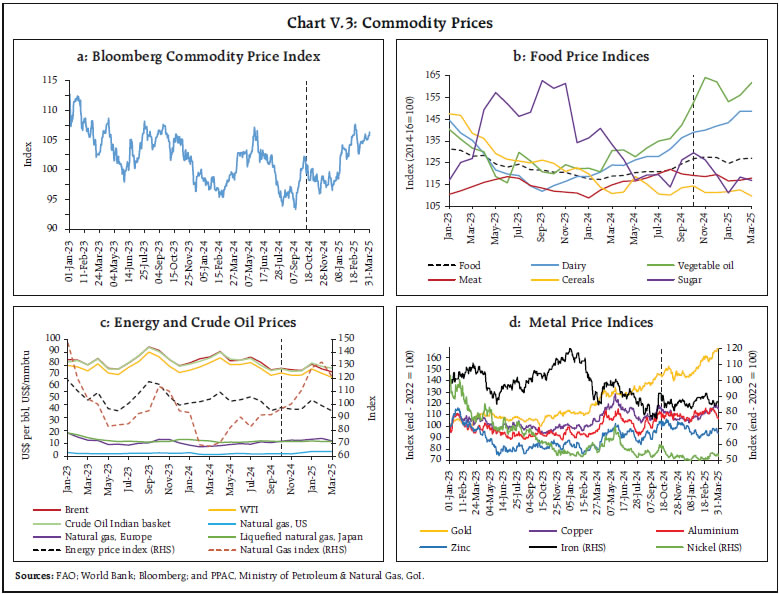

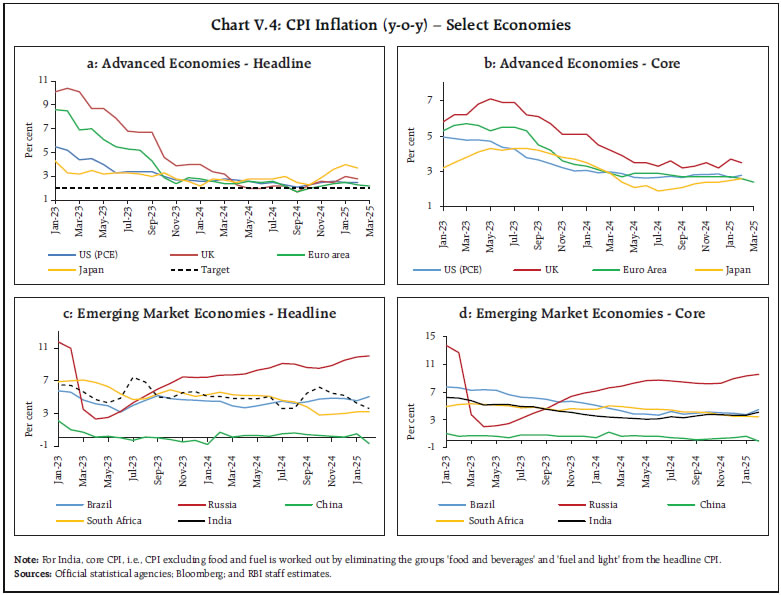

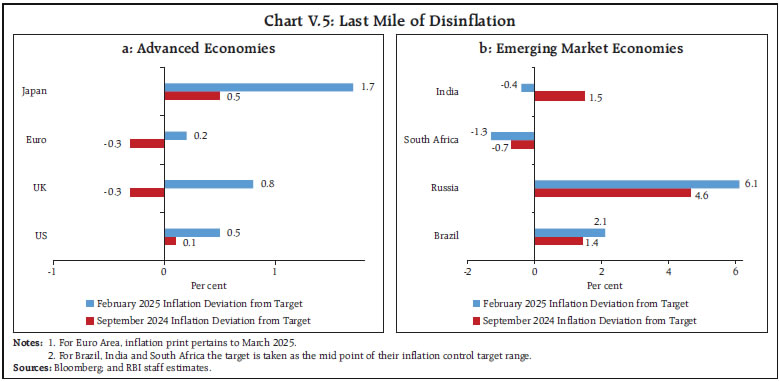

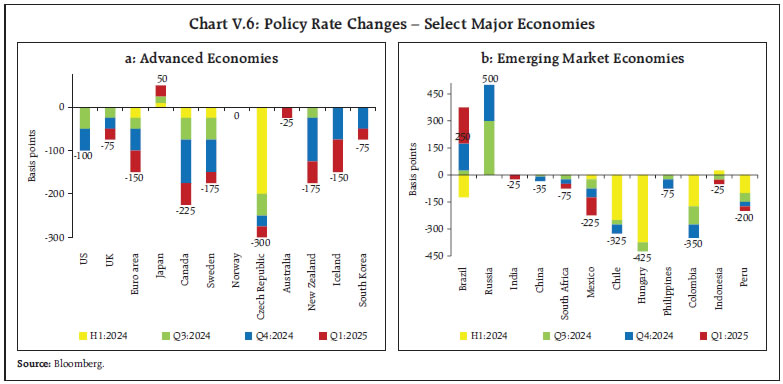

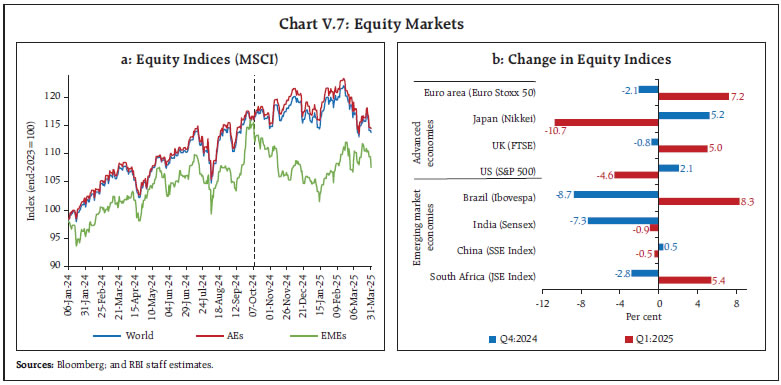

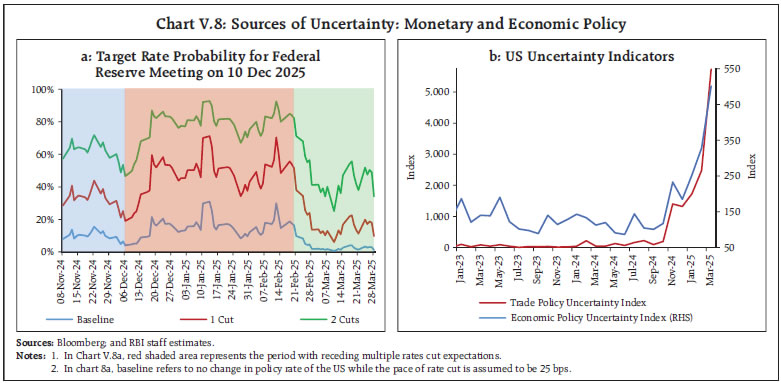

| I. Macroeconomic Outlook The domestic economic outlook remains resilient supported by improved consumption demand and strong macroeconomic fundamentals. Inflation is expected to align with the target on account of favourable food inflation outlook. Heightened trade tensions, volatile financial markets, geopolitical strife, and climate risks weigh heavily on the outlook. Monetary policy aims to facilitate conducive macroeconomic conditions that reinforce price stability and sustained economic growth. I.1 Key Developments since the October 2024 MPR Since the release of the Monetary Policy Report (MPR) in October 2024, global economic activity has remained resilient in 2024 although below historical average, with high frequency indicators hinting at slowdown in growth momentum in 2025. Escalating trade tensions led by a slew of tariff impositions impart uncertainty to the growth outlook. Headline inflation though decelerating, has remained above the target in many economies owing to the lacklustre and uneven pace of disinflation. The decline in headline inflation on account of subdued core inflation (i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel) augurs well, although persistent high services inflation weighs heavily on the outlook. The divergence in monetary policy pathways across countries has continued. As compared to the highly synchronous tightening phase, there is now a hesitant and guarded rate cut cycle under progress. Financial markets have been on edge due to shifting expectations of monetary policy and fears of tariff wars. Geopolitical uncertainties, ratcheting up of trade tensions and withdrawal of portfolio investors caused retreat in equities from the highs in January 2025. The sell off further intensified since March due to fears of trade war. Sovereign bond yields in advanced economies (AEs) hardened in Q4:2024 but have softened thereafter due to growth slowdown concerns. Gold prices continued to strengthen and reached new heights every month in 2025 till March. The US dollar index firmed in Q4:2024 due to delayed expectations of rate easing by the US Federal Reserve and anticipated policies of the new US administration but has retreated since mid-January 2025 amidst weaker growth expectations and heightened trade policy uncertainty. Global commodity prices softened somewhat in Q4:2024 but increased sharply in Q1:2025, largely on account of metals and agricultural prices. Brent crude oil prices rose sharply from late December 2024 till mid-January 2025, reflecting sanctions on Russia's energy sector, threats of tariff imposition, and cold weather conditions. It has softened since then following a moderation in geopolitical risk premium and improved supply response from Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries plus (OPEC+). Of late, energy and metal prices have softened after the tariff imposition owing to uncertain global economic outlook. Turning to the domestic economy, the second advance estimates (SAE) released by the national statistical office (NSO) estimated real gross domestic product (GDP) growth at 6.5 per cent year-on-year (y-o-y) in 2024-25 on the back of robust growth in private final consumption expenditure. On the supply side, real gross value added (GVA) expanded by 6.4 per cent, y-o-y, driven by agriculture and services sectors. Real GDP growth for Q3:2024-25 was placed at 6.2 per cent y-o-y, driven by robust private and government consumption expenditure. Headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation, which averaged 4.6 per cent during H1:2024-25, increased to 6.2 per cent in October 2024 but has since been easing with February 2025 inflation print at a seven month low of 3.6 per cent, driven by sharp decline in vegetable prices inflation. Core inflation which averaged 3.3 per cent in H1:2024-25, however, inched up to an average of 3.8 per cent in H2:2024-25 (up to February). On the contrary, food inflation which remained elevated at an average of 8.5 per cent during October- December 2024, decelerated to 3.8 per cent in February 2025. The deflation in fuel inflation, however, moderated. After retaining the policy repo rate at 6.5 per cent since February 2023, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has embarked on monetary easing in H2:2024-25. It changed the stance from withdrawal of accommodation to neutral in October 2024, and cut the policy repo rate by 25 basis points (bps) to 6.25 per cent in its February 2025 meeting. In December 2024, the Reserve Bank reduced the cash reserve ratio (CRR) maintained by banks by 50 bps. Monetary Policy Committee Meetings: October 2024 - March 2025 When the MPC met in October 2024, the global economy exhibited resilience, although intense geopolitical conflicts, geoeconomic fragmentation, financial market volatility and elevated public debt continued to pose downside risks. Inflation was softening but the growing divergence in growth-inflation dynamics across countries resulted in varying monetary policy responses. Domestically, real GDP registered a growth of 6.7 per cent, y-o-y, in Q1:2024-25, mainly driven by private consumption and investment. The outlook for agriculture remained positive, with above average rainfall, better kharif sowing and healthy reservoir levels. Manufacturing activity gained momentum due to improved domestic demand, lower input costs and a supportive policy environment while services sector growth remained robust. Investment activity was expected to stay buoyant due to resilient bank credit growth, higher capacity utilisation, healthy balance sheet of banks and government’s thrust on infrastructure spending. Real GDP growth for 2024-25 was projected at 7.2 per cent. Headline inflation fell sharply from 5.1 per cent in June to 3.6 per cent and 3.7 per cent in July and August, respectively. Deflation in fuel further deepened but core inflation edged up. After a transient spike in the near term, headline inflation was expected to moderate. Considering the major upside risks on account of unexpected weather events and worsening of geopolitical conflicts, the projection of CPI inflation for 2024-25 was retained at 4.5 per cent. By a majority of 5-1, the MPC decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.5 per cent emphasising the need to remain vigilant of the evolving inflation outlook. Keeping in view the well-balanced growth-inflation dynamics, the MPC also unanimously decided to change the stance from ‘withdrawal of accommodation’ to ‘neutral’ to provide flexibility to monitor and assess the outlook on inflation and growth and act in accordance with the evolving situation while remaining unambiguously focused on achieving a durable alignment of inflation with the target, while supporting growth. At the time of the December 2024 meeting, the global economy was steady even as inflation was easing. However, geopolitical risks and policy uncertainty, particularly trade policies, resulted in heightened volatility in financial markets. On the domestic front, real GDP growth of 5.4 per cent in Q2:2024-25 was much lower than expected as expansion in private consumption and investment decelerated, although government spending recovered during the quarter, Real GVA growth was tempered by deceleration in growth of industrial activity reflecting subdued performance of manufacturing companies, contraction in mining activity and lower electricity demand. Real GDP growth for 2024-25 was projected at 6.6 per cent. Headline CPI inflation increased to 6.2 per cent in October breaching the upper tolerance band, driven by an unanticipated rise in food prices. Core inflation also registered an uptick in October. CPI inflation projection for 2024-25 was revised upwards to 4.8 per cent. The MPC emphasised on the importance of maintaining price stability as a foundation for long-term high economic growth and remained committed towards restoring the growth-inflation balance in the overall interest of the economy. It decided by a majority of 4-2 to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.5 per cent and voted unanimously to continue with the neutral stance. In the run up to the February 2025 meeting, the global economic landscape remained challenging with global growth being below the historical average although high frequency indicators showed signs of resilience along with expansion in world trade. The pace of disinflation was marred by services price inflation. Strengthening dollar exerted pressure on emerging market currencies and imparted volatility in financial markets. On the domestic front, real GDP growth, as per the first advance estimates (FAE) of the NSO, was estimated to grow at 6.4 per cent in 2024-25, underpinned by a recovery in private consumption. Looking ahead, improved rabi prospects and recovery in industrial activity was expected to support growth in 2025-26. Real GDP growth for 2025-26 was projected at 6.7 per cent. Headline inflation softened sequentially in November and December from its October high driven by the moderation in food inflation, which was aided by easing of vegetable prices. Core inflation remained subdued and fuel deflation continued. Inflationary pressures were expected to moderate in the near term, due to good kharif production, easing in vegetable prices and favourable rabi crop prospects while continued uncertainty in global financial markets, volatility in energy prices and adverse weather events posed upside risks. CPI inflation projection for 2024-25 was retained at 4.8 per cent. Also, assuming a normal monsoon next year, CPI inflation for 2025-26 is projected at 4.2 per cent. The MPC noted that inflation is on a declining trajectory largely due to favourable outlook on food prices and impact of past monetary policy measures and is further expected to moderate in 2025-26, gradually aligning with the target. Therefore, the evolving growth-inflation dynamics opened up space to support growth. Accordingly, the MPC unanimously voted to reduce the policy repo rate by 25 bps to 6.25 per cent. The MPC also decided to continue with the neutral stance so as to retain the flexibility to respond to the evolving macroeconomic environment. | Table I.1 Monetary Policy Committee Meetings and Policy Rate Voting Patterns | | Country | Policy Meetings: October 2024 - March 2025 | | Total meetings | Meetings with full consensus | Meetings without full consensus | Variation in policy rate (basis points) | | Brazil | 4 | 4 | 0 | 350 | | Chile | 4 | 4 | 0 | -50 | | Colombia | 4 | 0 | 4 | -75 | | Czech Republic | 4 | 2 | 2 | -50 | | Hungary* | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | | India | 3 | 1 | 2 | -25 | | Japan | 4 | 2 | 2 | 25 | | South Africa | 3 | 1 | 2 | -50 | | Sweden | 4 | 4 | 0 | -100 | | Thailand | 3 | 1 | 2 | -50 | | UK | 4 | 0 | 4 | -50 | | US | 4 | 3 | 1 | -50 | Note: *: Total number of meetings happened is six. However, the minutes of last meeting (March 25, 2025) is not published to date.

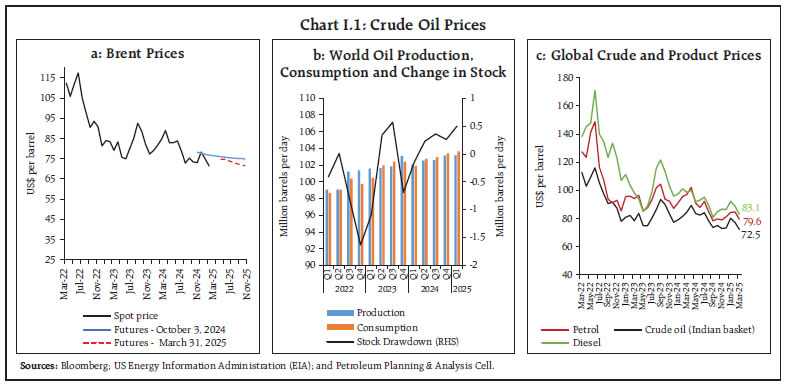

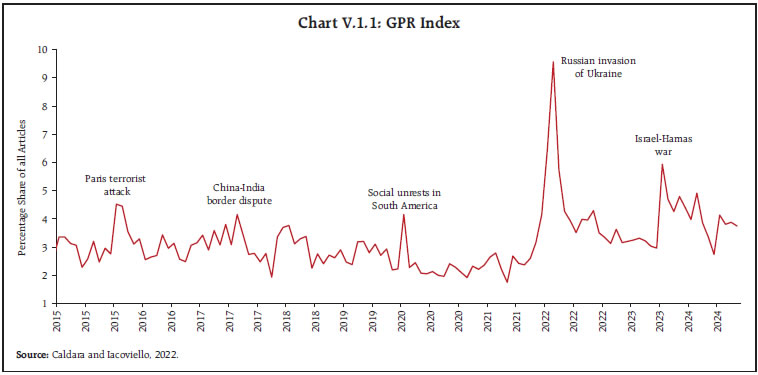

Sources: Central bank websites. | The MPC’s voting pattern reflects the diversity in individual members’ assessments, expectations and policy preferences - a characteristic also reflected in voting patterns of other central banks (Table I.1). While most AEs and emerging market economies (EMEs) undertook policy easing, concerns on slower pace of disinflation compounded by developments on the geopolitical front and trade fragmentation suggested shallow rate cut cycle amidst policy uncertainties. Few exceptions like Japan and Brazil which continued with monetary tightening to keep inflation around their respective targets. Macroeconomic Outlook Chapters II and III analyse macroeconomic developments relating to inflation and economic activity during H2:2024-25 (October 2024 - March 2025). Turning to the baseline assumptions, international crude prices exhibited declining pattern during October-December 2024, hovering around US$ 74 per barrel on account of relatively modest growth in global oil demand as well as robust supply from non-OPEC countries. Anxiety over the impact of sanctions over Russia and speculation of increased restrictions on Iran, along with fears of potential supply disruptions, triggered an upswing in prices in early January to around US$ 84 per barrel. Since then, prices gradually declined in February and fell to its lowest levels in recent times in March 2025 primarily due to announcement of production increase by OPEC along with reduced geopolitical risk premiums and adequate inventory. Geopolitical developments continue to impart significant uncertainty to the outlook (Charts I.1a and I.1b). The spread between global petroleum product prices and crude prices softened (Chart I.1c). Considering these factors, the baseline assumption for crude price (Indian basket) is reduced to US$ 70 per barrel during 2025-26 (Table I.2). | Table I.2: Baseline Assumptions for Projections | | Indicator | MPR October 2024 | MPR April 2025 | | Crude Oil (Indian Basket) | US$ 80 per barrel during H2: 2024-25 | US$ 70 per barrel during 2025-26 | | Exchange rate | ₹83.50/US$ during H2: 2024-25 | ₹86/US$ during 2025-26 | | Monsoon | Normal for 2025-26 | Normal for 2025-26 | | Global growth | 3.2 per cent in 2024

3.3 per cent in 2025 | 3.1 per cent in 2025

3.0 per cent in 2026 | | Fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | To remain within BE 2024-25

Centre: 4.9

Combined:7.3 | To remain within BE 2025-26

Centre: 4.4

Combined: 7.1 | | Domestic macroeconomic/ structural policies during the forecast period | No major change | No major change | Notes: 1. The Indian basket of crude oil represents a derived numeraire comprising sour grade (Oman and Dubai average) and sweet grade (Brent) crude oil.

2. The exchange rate path assumed here is for the purpose of generating the baseline projections and does not indicate any ‘view’ on the level of the exchange rate. The Reserve Bank is guided by the objective of containing excess volatility in the foreign exchange market and not by any specific level of and/or band around the exchange rate.

3. BE: Budget estimates.

4. Combined fiscal deficit refers to that of the Centre and States taken together.

Sources: RBI estimates; Budget documents; International Monetary Fund (IMF); and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). | Second, the nominal exchange rate of the Indian rupee (₹) saw two-way movements in the range of ₹83.8-87.6 per US dollar during H2:2024-25 with a depreciating bias in 2025 till early March. The strengthening of US dollar since early October 2024 resulted in depreciation of EME currencies including rupee and increased volatility in financial markets. Since mid-January, however, the dollar has retreated with high frequency indicators pointing towards lacklustre growth and elevated policy uncertainty. Accordingly, EME currencies have recovered, albeit not fully. Taking into consideration the uncertainty around US dollar movements, fluctuations of global capital flows and international crude oil prices, the baseline assumption for the exchange rate is revised to ₹86 per US dollar as against ₹83.50 in the October 2024 MPR.  Third, global growth was projected at 3.1 per cent in 2025 and 3.0 per cent in 2026 by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in its Economic Outlook Interim Report released in March 2025. The global disinflation continues, with inflation expected to decline to 4.2 per cent in 2025 and to 3.5 per cent in 2026, according to World Economic Outlook in its January 2025 update by International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Chart I.2). Global trade growth (goods and services combined) is projected to decelerate from 3.4 per cent in 2024 to 3.2 per cent in 2025 before rebounding to 3.3 per cent in 2026. The recent reciprocal tariff announcements by the US administration and associated policy uncertainty, however, poses headwinds to global growth and inflation.

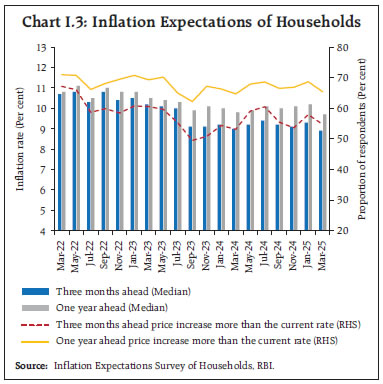

I.2 The Outlook for Inflation In H2:2024-25 so far (up to February), headline inflation breached the upper tolerance band briefly in October 2024, but has since eased on the back of declining food inflation. In the March 2025, round of the Reserve Bank’s households survey1, the three months and one year ahead inflation expectations of urban households’ decreased by 40 bps and 50 bps, reaching 8.9 per cent and 9.7 per cent, respectively, as compared to the January 2025 round. The proportion of respondents expecting the general price level to increase by more than the current rate declined for both horizons vis-à-vis the previous round (Chart I.3). In this context, it is pertinent to note that various economic agents form their inflation expectations based on different factors (Box I.1).

Box I.1: What Affects Inflation Expectations of Economic Agents? Anchoring inflation expectations is paramount in monetary policy formulation, particularly in an inflation-targeting framework. Empirical evidence suggests that positive changes in interest rates cause inflation expectations to decline (Goncalves et al., 2025). However, monetary responses of different agents vary, i.e., different categories of respondents respond differently to changes in monetary policy. An increase in the repo rate was found to have a sobering impact on inflation expectations of the financial and business sector agents but have a contrary impact for trade unions (Mlangeni and Buthelezi, 2023). To examine this phenomenon in the Indian context, a vector error correction model (VECM) is used to explore the relationship between key indicators and inflation expectations of different economic agents such as financial sector employees, daily workers, and self-employed workers, using the bi-monthly inflation expectations data from January 2017 to January 2025 with the following specification: where xt is the vector of endogenous variables, α is the adjustment coefficient and βt is the cointegrating vector (which defines the long-term relationship between the variables) and ϵt is the error term. The model is defined as follows: where Yt is one year ahead inflation expectations of financial sector employees, daily workers, and the self-employed, wacr is the weighted average call rate representing monetary policy; inflation is CPI inflation; govt_share is the share of government expenditure in GDP and ln_crude_oil represents natural logarithm of global crude oil prices which is an average of Brent, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) spot and Dubai Fateh. The unit root test suggests that all variables are integrated of order 1. Using appropriate lag length criteria, Johansen Cointegrating test finds a cointegrating relationship among the variables. The results suggest that monetary policy changes have a differential impact on inflation expectations of various groups. Inflation expectations are found to be negatively associated with the change in the policy interest rate in the long-run for financial sector employees and the self-employed. Also, financial sector employees are found to have a higher adjustment factor as compared to other groups, which suggest faster reaction to any deviation in actual inflation from the long-run steady state. Past inflation impacts positively in the formation of inflation expectations for all groups suggesting persistence. In contrast, crude oil prices are found to impact inflation expectations of self-employed and daily workers only (Table 1). Overall, the findings suggest that the formation of inflation expectations of different economic agents are governed by diverse factors corroborating cross-country experience. | Table 1: Long Run Estimates of VEC Model | | Variable | Financial sector employees | Daily workers | Self employed | | wacr(-1) | -0.297* | -0.260 | -0.407* | | | (0.113) | (0.136) | (0.121) | | inflation(-1) | 0.443** | 0.529*** | 0.526*** | | | (0.095) | (0.115) | (0.102) | | govt_share(-1) | 0.053 | -0.229** | -0.059 | | | (0.056) | (0.067) | (0.060) | | ln_crude_oil | 1.248 | 4.127*** | 3.901*** | | | (0.509) | (0.617) | (0.546) | | constant | 2.451 | -5.017 | -5.977 | | | (1.987) | (2.409) | (2.131) | | Error Correction, α | -0.904** | -0.278* | -0.417* | | | (0.132) | (0.094) | (0.125) | | R-squared | 0.503 | 0.158 | 0.193 | | Johansen cointegration test for no. of C.E. | 2 | 2 | 2 | | Observations | 49 | 49 | 49 | Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

C.E. denotes cointegrating equations

Source: RBI staff estimates. | References: 1. Goncalves, M., Rodrigues, M., and Genta, F (2025). “Monetary Policy and Inflation Expectations: High- Frequency Evidence from Brazil”, IMF Working Paper WP/25/48. 2. Mlangeni, T., and Buthelezi, E. M (2023). “Monetary policy and inflation expectations: impact and causal analysis of heterogeneous economic agents’ expectations in South Africa”, Journal of Applied Economics, 27:1. |

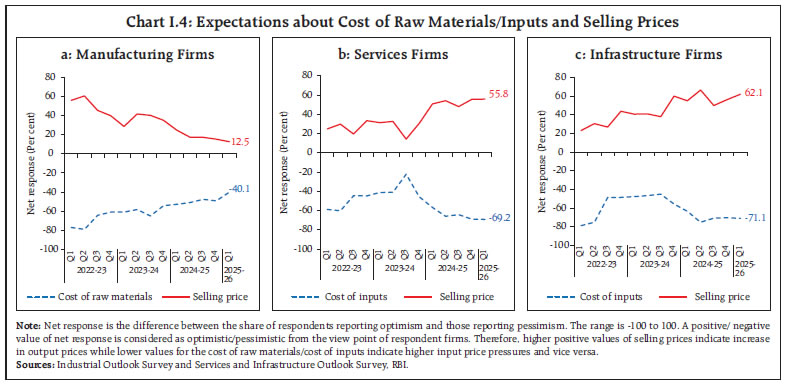

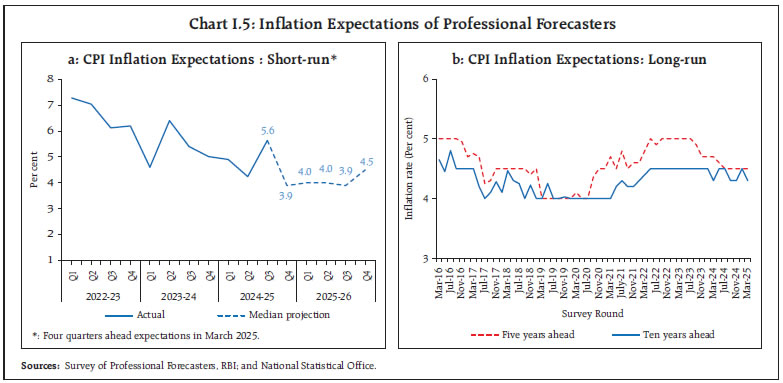

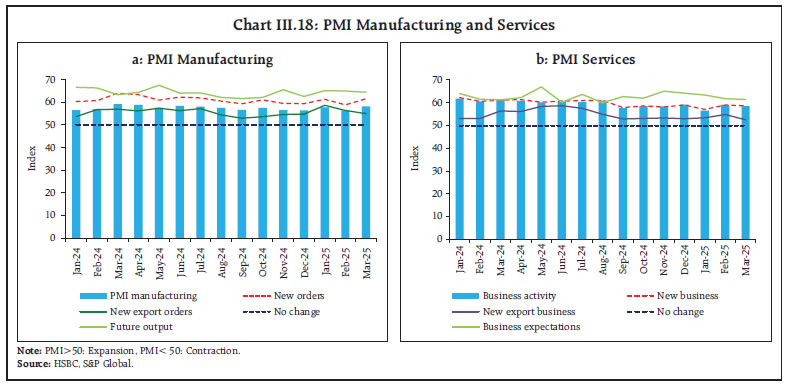

Manufacturing firms polled in the January-March 2025 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey expect pressures from cost of raw materials to ease and growth in selling price to moderate in Q1:2025-26 vis-à-vis the previous quarter (Chart I.4a).2 Both services sector companies and infrastructure firms expect higher input cost pressures and higher output prices in Q1:2025-26 (Charts I.4b and I.4c).3 In the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) surveys for March 2025, input prices increased for manufacturing firms and declined for services firms vis-à-vis the previous month while output prices declined for both. Professional forecasters surveyed by the Reserve Bank in March 2025 projected CPI inflation to decline from 5.6 per cent in Q3:2024-25 to 3.9 per cent in Q4. They expect it to remain around 3.9-4.0 per cent till Q3 of 2025-26 before increasing to 4.5 per cent in Q4:2025-26 (Chart I.5a and Table I.3).4 Core inflation (i.e., CPI excluding food and beverages, pan, tobacco and intoxicants, and fuel and light) is expected to be at 4.0 per cent during Q4:2024-25, thereafter, it is expected to remain around 4.2-4.3 per cent till Q3:2025-26 and at 4.5 per cent in Q4. Long-run inflation expectations of professional forecasters – measured by their 5 and 10 years ahead expectations – are at 4.5 per cent and 4.3 per cent, respectively, in the current round (Chart 1.5 b). Looking ahead, the inflation outlook will be conditioned by several factors, both global and domestic. Food inflation may continue to ease due to robust kharif harvest arrivals which, coupled with promising rabi crop, bode well for inflation outlook. The Union Budget proposals on agriculture and the commitment to fiscal consolidation further strengthens the inflation outlook. However, lingering uncertainty in global financial markets, volatility in energy prices, adverse weather events, rising global supply chain pressures and continuing geopolitical strife remain key risks.  Taking into account the initial conditions, signals from forward-looking surveys and estimates from time-series and structural models5, CPI inflation is projected to average 4.0 per cent in 2025-26 – 3.6 per cent in Q1, 3.9 per cent in Q2, 3.8 per cent in Q3 and 4.4 per cent in Q4, with risks evenly balanced (Chart I.6 and Table I.3). The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for headline inflation in Q4:2025-26 are 2.8-6.0 per cent and 1.9-6.9 per cent, respectively. For 2026-27, assuming a normal monsoon, and no further exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates indicate that inflation will average 4.3 per cent with 4.5 per cent in Q1, 4.3 per cent in Q2, 4.4 per cent in Q3 and 4.3 per cent in Q4. The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for headline inflation in Q4:2026-27 are 2.6- 6.0 per cent and 1.7-6.9 per cent, respectively. | Table I.3: Projections - Reserve Bank and Professional Forecasters | | (Per cent) | | | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | | Reserve Bank’s Baseline Projections | | | | | Inflation | 4.7* | 4.0 | 4.3 | | Real GDP growth | 6.5@ | 6.5 | 6.7 | | Median Projections of Professional Forecasters | | | | | Inflation, Q4 (y-o-y) | 3.9 | 4.5 | - | | Real GDP growth | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.6 | | Gross domestic saving (per cent of GNDI) | 30.2 | 30.4 | 30.3 | | Gross capital formation (per cent of GDP) | 31.0 | 30.7 | 31.1 | | Credit growth of scheduled commercial banks | 11.5 | 12.3 | 13.5 | | Combined gross fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.1 | | Central government gross fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.3 | | Repo rate (end-period) | 6.25 | 5.75 | - | | Yield on 91-days treasury bills (end-period) | 6.5 | 6.0 | 6.4 | | Yield on 10-year central government securities (end-period) | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.5 | | Overall balance of payments (US$ billion) | 4.1 | 17.0 | 24.1 | | Merchandise exports growth | -0.2 | 3.5 | 5.0 | | Merchandise imports growth | 4.6 | 4.5 | 5.5 | | Current account balance (per cent of GDP) | -0.8 | -1.0 | -1.0 | Notes: GNDI: Gross National Disposable Income.

@: NSO Second Advance Estimates;

*: Average CPI Inflation in 2024-25 (up to February).

Sources: RBI staff estimates; and Survey of Professional Forecasters (March 2025). | The baseline forecasts are subject to several upside and downside risks. The upside risks emanate from continuing geopolitical conflicts and resultant supply disruptions; volatility of energy prices; and adverse weather events. The downside risks could emanate from an early resolution of geopolitical conflicts; adherence to fiscal consolidation and debt path; further correction in global crude and commodity prices in case of slowing global demand; and improvement in supply conditions. I.3 The Outlook for Growth Domestic economic activity remains strong supported by revival in consumption as well as government’s capex push. Pick up in private consumption, upturn in agricultural activity, continuing resilience of the services sector, high capacity utilisation, healthy balance sheets of banks and corporates, and government’s continued thrust on capital expenditure augur well for the growth outlook. Uncertainty about global trade owing to rising protectionist measures, persistent geopolitical tensions, rising supply chain pressures, and volatile global financial conditions, however, render the outlook uncertain. Turning to the key messages from forward-looking surveys, consumer confidence (the current situation index) improved in the pessimistic territory in March 2025 vis-à-vis the previous round, driven by improved sentiments across all survey parameters6. Consumers’ optimism for the year ahead, measured by the future expectations index, strengthened further and maintained its resilience in the optimistic territory (Chart I.7). Reserve Bank's industrial outlook survey results reveal that business optimism in the manufacturing sector for Q1:2025-26 moderated marginally, which is partly seasonal (Chart I.8a). The services and infrastructure companies, on the other hand, remained optimistic about the overall business situation in Q1:2025-26 (Charts I.8b and I.8c). Recent surveys by other agencies indicate a mixed picture on business expectations relative to the previous round (Table I.4). In the PMI surveys for March 2025, manufacturing firms remained upbeat about the year ahead though sentiments moderated for services firms. Professional forecasters polled in the March 2025 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey expected real GDP growth at 7.0 per cent during the last quarter of 2024-25. Growth is expected at 6.5-6.7 per cent during Q1-Q4:2025-26 (Chart I.9 and Table I.3). Real GDP growth was higher at 6.2 per cent in Q3:2024-25 as compared with 5.6 per cent in Q2. Taking into account the baseline assumptions, survey indicators and model forecasts, real GDP growth is expected at 6.5 per cent in 2025-26 – 6.5 per cent in Q1; 6.7 per cent in Q2; 6.6 per cent in Q3 and 6.3 per cent in Q4 – with risks evenly balanced around this baseline path (Chart I.10 and Table I.3). Assuming a normal monsoon and no major exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates for 2026-27 indicate real GDP growth at 6.7 per cent, with Q1 at 6.5 per cent, Q2 at 6.4 per cent, Q3 at 6.8 per cent and Q4 at 6.8 per cent. | Table I.4: Business Expectations Surveys | | Item | NCAER Business Confidence Index (January 2025) | FICCI Overall Business Confidence Index (November 2024) | Dun and Bradstreet Composite Business Optimism Index (April 2025) | CII Business Confidence Index (March 2025) | | Current level of the index | 138.4 | 62.5 | 120.2 | 63.7 | | Index as per previous survey | 134.3 | 67.3 | 114.4 | 66.2 | | % change (q-o-q) sequential | 3.0 | -7.1 | 5.1 | -3.8 | | % change (y-o-y) | 8.5 | -6.6 | 11.2 | -6.8 | Notes: 1. NCAER: National Council of Applied Economic Research.

2. FICCI: Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry.

3. CII: Confederation of Indian Industry.

4. Dun and Bradstreet Composite Business Optimism Index is for Q1:2025-26, CII Business Confidence Index is for Q4:2024- 25, FICCI Overall Business Confidence Index is for Q2:2024-25, and NCAER Business Confidence Index is for Q3:2024-25

Sources: NCAER, FICCI, CII and Dun & Bradstreet Information Services India Pvt. Ltd. |

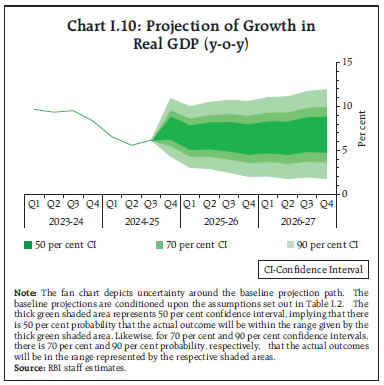

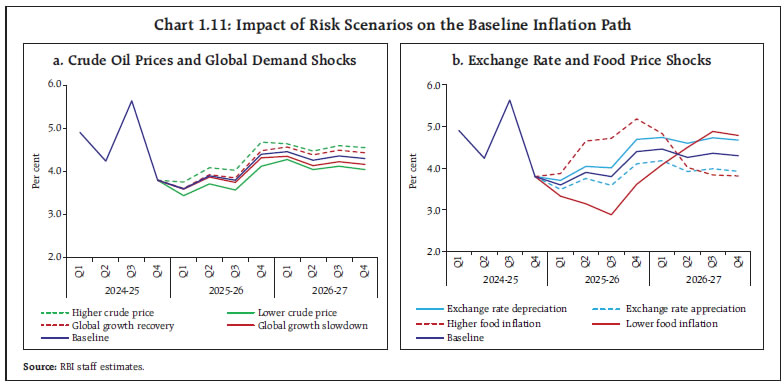

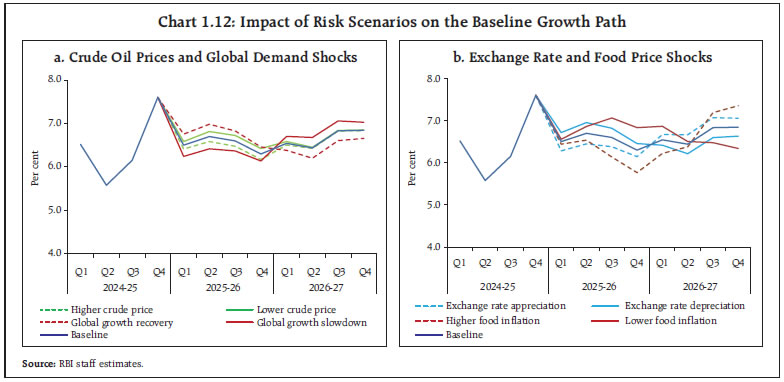

There are upside and downside risks to this baseline growth path. The upside risks emanate from revival in corporate investment cycle; improving business sentiments; faster global disinflation; quick resolution of global trade related issues; continued softening of global commodity prices; and an early resolution of the geopolitical conflicts. On the contrary, increasing trade fragmentation due to protectionist policies including higher tariffs; further escalation in geopolitical tensions; volatility in international financial markets; frequent weather-related disturbances; and supply chain disruptions pose downside risks to the baseline growth path. I.4 Balance of Risks The baseline projections of growth and inflation are based on the set of assumptions related to the likely path of key domestic and global macroeconomic variables which are set out in Table 1.2. These baseline assumptions are, however, subject to uncertainties emanating from reciprocal and retaliatory tariffs owing to protectionist trade policies adopted by major economies, prolonged geopolitical conflicts, volatility in global financial and commodity markets and possibility of adverse climate events. Against this backdrop, this section explores the plausible alternative scenarios to assess the balance of risks around the baseline projections of inflation and growth. (i) Global Growth Uncertainties Global economic activity remained steady in H2:2024, albeit marred by sluggish growth recorded by some Asian and European economies as weakness in manufacturing and trade exports offset the robust growth momentum in the United States. Going forward, however, global growth is prone to considerable uncertainties. Trade tensions and geopolitical conflicts between major economies are bound to create uncertainties in global financial markets, trigger a slowdown in global trade and create disruptions in supply chains. Additionally, protectionist trade policies including reciprocal tariffs will further fragment global trade and have an adverse impact on growth prospects leading to potential increase in input costs for businesses. Major central banks could also diverge in the pace and direction of monetary policy actions in achieving the last mile of disinflation, inducing higher volatility in global financial markets with spillover effects on EMEs. Global economic outlook is also subject to headwinds from fiscal sustainability concerns, occurrence of extreme weather events and technological disruptions. If some of these scenarios materialise, and if global growth turns out to be 100 bps lower than assumed in the baseline, domestic growth and inflation could be lower by around 30 bps and 15 bps, respectively, in comparison with the baseline projections. However, if there is a faster recovery in global trade owing to quicker resolution of trade related issues between the major economies and synchronised accommodative monetary policy due to benign inflation outlook going forward, global growth prospects may improve. If global growth is higher by 50 bps relative to the baseline, domestic growth and inflation could turn out to be higher by around 15 bps and 7 bps, respectively (Charts I.11a and I.12a).  (ii) International Crude Oil Prices Global crude oil prices have exhibited a declining trend with Brent crude falling from a high of US$ 82 per barrel in early-October 2024 to an average of US$73 per barrel in March 2025. Weak global demand conditions, sustained supply increase from OPEC+ and non-OPEC countries and orderly resolution of geo-political conflicts will have a potential dampening impact on crude oil prices. In this scenario, if crude oil prices drop by 10 per cent relative to the baseline, and in case of its full pass-through to domestic product prices, inflation could be lower by around 30 bps with a boost of 15 bps to India’s real GDP growth. In contrast, recovery in global demand, and restriction in oil supplies due to continuation of geo-political tensions may put upward pressure on crude oil prices. In a scenario, when crude oil prices are higher by 10 per cent than the baseline assumption, domestic inflation may turn out to be higher by 30 bps and growth may be weaker by around 15 bps. (Charts I.11a and I.12a). (iii) Exchange Rate The Indian Rupee depreciated vis-à-vis the US dollar during October 2024-March 2025, primarily reflecting the uncertainties due to disruptions in global trade, strengthening of the US dollar and capital outflows reflecting ‘flight to safety’. Going ahead, restrictive monetary policy by the US Federal Reserve than what has been currently factored in by the financial markets could further lower the attractiveness of EME assets. Rising trade protectionism, currency war threats, and higher international crude oil prices are also some of the factors that may exert downward pressure on the Indian rupee. In this scenario, if INR depreciates by 5 per cent over the baseline, inflation could rise by around 35 bps while GDP growth could benefit by around 25 bps through the trade channel in the short term. On the other hand, the Indian economy exhibits continued resilience in growth with a stable inflation outlook and is expected to contribute to revival of global demand conditions. These developments, along with faster resolution of trade protectionism and quicker than anticipated monetary policy easing by major economies, would lead to strengthening of the Indian Rupee. In this scenario, if the INR appreciates by 5 per cent relative to the baseline, inflation and GDP growth could moderate by around 35 bps and 25 bps, respectively (Charts I.11b and I.12b).  (iv) Food Inflation Food inflation witnessed moderation in H2:2024-25 after scaling its peak in October 2024, primarily driven by sharp seasonal correction in vegetable prices, lower cereals and pulses inflation and deflation in spices. Going ahead, food prices may soften faster supported by robust kharif crop production and likely bumper rabi arrivals. In such a scenario, headline inflation may moderate by around 50 bps over the baseline. On the other hand, sudden reversal in the prices of perishable food items and reduction of agricultural yields due to adverse climatic conditions may exert upward pressure on food prices. These factors could lead to higher headline inflation by 50 bps as compared to the baseline (Charts I.11b and I.12b). I.5 Conclusion Domestic economic activity is on a recovery path and is expected to remain resilient backed by consumption demand. It needs to be recognised that India’s forte is its high growth potential and robust macroeconomic fundamentals. Government's push for consumption and capex, resilient services sector, robust outlook of agricultural sector aided by strong corporate and bank balance sheets provide impetus to the growth momentum, going forward. The measures announced in the Union Budget 2025-26 augur well for improving domestic consumption. Moreover, the adherence to fiscal consolidation and debt path without compromising on the quality of expenditure will help in improving sovereign ratings, attracting capital inflows, easing financial conditions, and improving overall sentiment and outlook. Well-coordinated fiscal and monetary policy working in tandem could undoubtedly generate improved outcomes in terms of better growth-inflation balance. The recent tariff announcements by US administration have hightened policy uncertainty posing new headwinds for global growth and inflation. While India cannot remain immune to these developments, the progress achieved on the disinflation front gives headroom to monetary policy to focus on balancing the growth-inflation outcome. _________________________________________________________________________________

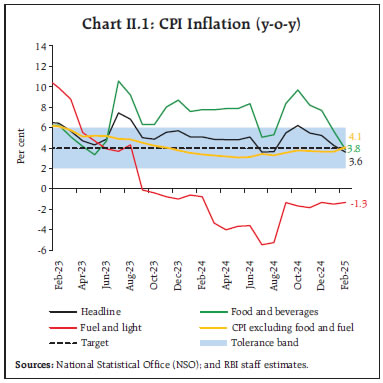

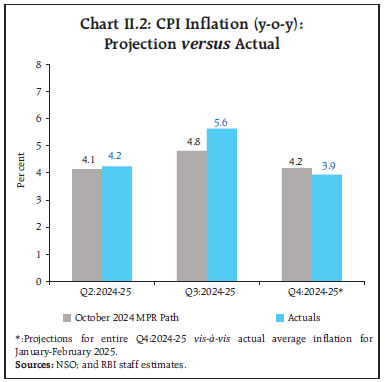

II. Prices and Costs Headline inflation has been marked by considerable volatility during H2:2024-25, engendered by overlapping food price shocks. As the impact of shocks receded, a sharp correction followed, resulting in headline inflation declining below the target rate of 4 per cent by February 2025. Core inflation pressures were muted in H2, though February saw a notable pick-up. Industrial and farm input costs remained subdued. Nominal rural wage growth stayed elevated, driven by agricultural wages, while the organised sector staff cost growth decelerated. Movements in headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation1 since August 2024 were marked by considerable volatility engendered by overlapping food price shocks that pushed up headline inflation above the upper tolerance threshold of 6 per cent in October 2024. As the impact of shocks receded, a sharp correction followed, resulting in headline inflation declining below the target rate of 4 per cent by February 2025. Headline CPI inflation surged from 3.7 per cent in August to 6.2 per cent by October 2024, propelled by a jump in food inflation owing to a spike in prices of vegetables, and oils and fats. In the ensuing months, as food inflation eased on correction in vegetable prices, headline inflation softened successively to 4.3 per cent in January 2025 and further to 3.6 per cent in February. Reflecting the volatility in food inflation, the contribution of the food and beverages group (with a weight of around 46 per cent in the CPI basket) to headline inflation fell from an elevated 74 per cent in October 2024 to 50 per cent in February 2025. Deflation in the fuel group persisted, though the rate of deflation moderated from (-)5.3 per cent in August 2024 to (-)1.3 per cent in February 2025. Core (CPI excluding food and fuel) inflation2 remained muted, moving in a range of 3.5-3.8 per cent during September 2024 to January 2025, before firming up to 4.1 per cent in February 2025 (Chart II.1). The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 (amended in 2016) enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual inflation outcomes from projections, if any, and explain the underlying reasons thereof. The October 2024 MPR had projected inflation at 4.8 per cent in Q3:2024-25 and 4.2 per cent in Q4:2024-25 (Chart II.2). The deviations of the actual inflation outcomes from the projections were bi-directional – with inflation being higher than projections in Q3:2024-25 and lower than projections in Q4. The undershoot of projections by 80 basis points in Q3 arose primarily from an unanticipated transitory spike in prices of tomatoes due to weather disruptions and a rapid pick-up in domestic edible oil prices due to higher costs of imports. Thereafter, with vegetables prices registering a sharper than anticipated winter season price correction during January and February 2025, realised headline inflation at 3.9 per cent in Q4 so far (up to February) turned out to be 25 bps lower than the projections set out in the October 2024 MPR.

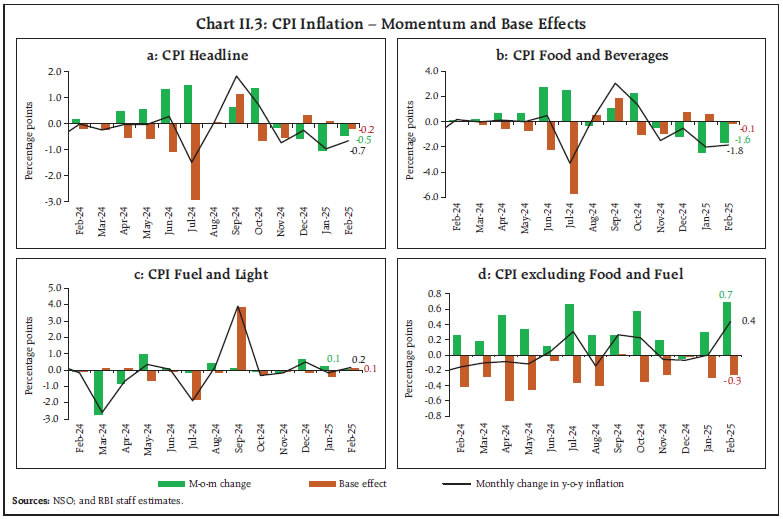

II.1 Consumer Prices The surge in headline inflation by 1.8 percentage points from 3.7 per cent in August 2024 to 5.5 per cent in September came from an uptick in price momentum3 along with sharp unfavourable base effects (1.1 percentage points). The headline CPI momentum quickened pace in October – primarily coming from a sharp increase in food prices – that firmed up headline inflation to 6.2 per cent, breaching the upper tolerance threshold, notwithstanding significant favourable base effects. Thereafter, with a sharp correction in the food price momentum, headline momentum began to register consecutive declines during November 2024-February 2025, resulting in a softening of headline inflation by 2.6 percentage points during this period to touch a low of 3.6 per cent in February. This decline was despite a sharp pick-up in core (CPI excluding food and fuel) momentum in February (Chart II.3).

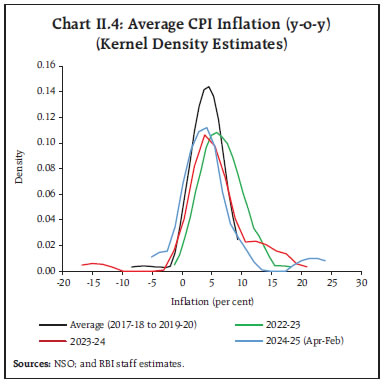

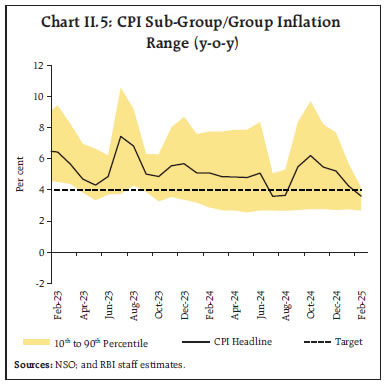

The distribution of CPI inflation in 2024-25 so far (April 2024-February 2025) vis-à-vis 2023-24 indicates high positive skew and relatively higher standard deviation, pointing to the outsized impact of continuing sectoral supply side shocks in engendering the persistence of headline inflation (Chart II.4). The pick-up in inflation during September-October was also marked by widening of inflation divergence across CPI sub-groups, reflecting the sharp increase in inflation across a few sub-groups. The pullback in inflation pressures across these sub-groups since December was also followed by a narrowing of the inflation divergence across quantiles (Chart II.5). An analysis of spatial inflation dynamics shows that even with sharp swings in inflation due to supply shocks, inflation across states has tended to converge to the national average during the Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) period (Box II.1).

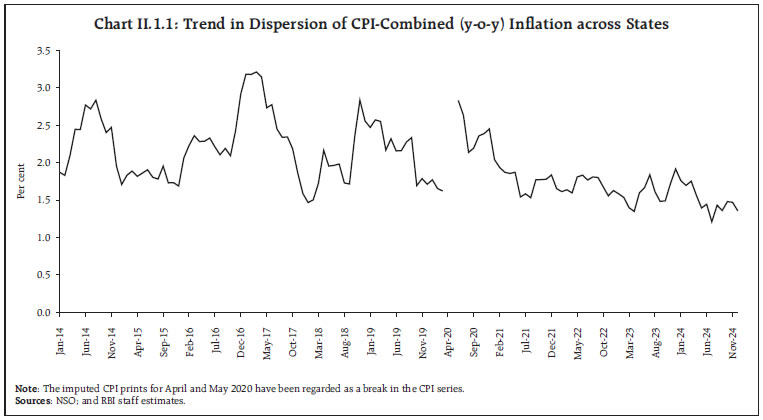

Box II.1: Spatial Inflation Convergence in India The period since the 2020s has been characterised by persistent inflationary pressures due to multiple overlapping shocks. It has also raised concerns about whether they have fundamentally altered spatial inflation dynamics in India – in terms of its volatility and convergence over time – with its attendant implications for monetary policy and the credibility of the 4 per cent CPI headline inflation target. Against this backdrop, spatial convergence properties of overall CPI inflation since the implementation of FIT in 2016 are examined, with a focus on the post-COVID period. Monthly year-on-year (y-o-y) changes in the CPI Combined Index as the measure of inflation across 35 Indian states and union territories spanning October 2016 to December 20244 are used for the analysis. It is observed that the headline inflation dispersion across states has moderated over time (Chart II.1.1). The spatial convergence properties are further examined by (a) panel unit root tests such as Levin-Lin-Chu and Im-Pesaran-Shin for stationarity, and (b) the beta (β) convergence analysis to ascertain whether states with higher initial differentials with the national inflation level experienced a faster decline in inflation over time, i.e., convergence to a common steady state. Accordingly, a panel regression framework is used with the following specification (1).

Where Δπdiffit is the rate of change in inflation differential of state i in period t with respect to the national level in the same period, πdiffit–1 is the one-period lagged inflation differential, β is the coefficient measuring speed of convergence, and α and ε are the constant and error terms, respectively. Additionally, the analysis performs (c) sigma (σ)-convergence test, for testing the movements of the cross-sectional dispersion (standard deviation) of inflation5 over time; and (d) the log-t and convergence club tests, for checking whether all units converge to a single equilibrium or whether they are divided into clusters or ‘clubs’ (presence of multiple equlibria). The results for both panel unit root tests reject the null hypothesis of ‘panels contain unit roots’, implying stationarity, i.e., supporting inflation convergence across states. Similarly, the results of the β-convergence test using a pooled ordinary least square (OLS)6 regression framework show negative and statistically significant beta coefficients for both FIT and post-COVID periods, confirming the existence of spatial inflation convergence to the national level. Furthermore, the σ-convergence test, which involves regressing the standard deviation of inflation across states on a time trend, yields a negative and significant coefficient, implying a decline in inflation dispersion over time, including the post-COVID period. The Phillips and Sul log-t test also indicates a convergence for the FIT period, with the club convergence test confirming the presence of a single club containing all 35 states (Table II.1.1). These findings indicate an ongoing convergence of inflation across states towards the national average with lower dispersion despite the impact of multiple adverse supply side shocks since early 2020, thereby indicating economic integration and anchoring of inflation expectations during FIT. | Table II.1.1: Results of Spatial Convergence Tests | | a. Panel Unit Root Tests | | Tests | Statistic | Null Hypothesis | | Levin–Lin–Chu unit-root test | -12.021*** | Panels contain unit roots | | Im–Pesaran–Shin unit-root test | -11.634*** | All panels contain unit roots | | b. Beta-convergence analysis | | Explanatory Variables | FIT

(October 2016 - December 2024) | Post-COVID

(June 2020 - December 2024) | | Lagged Inflation Differential | -0.040*** | -0.060*** | | | (0.011) | (0.009) | | Constant | -0.083 | -0.001 | | | (0.247) | (0.358) | | c. Sigma-convergence analysis | | Time Trend | -0.002*** | -0.007*** | | | (0.0003) | (0.0009) | | Constant | 3.224*** | 6.769*** | | | (0.266) | (0.656) | | d. Phillips and Sul log-t test | | log(t) | -0.878 | | | (0.829) | | t-stat | -1.059 | | No. of clubs identified | 1 (containing all 35 states) | | Note: Figures in parentheses indicate robust standard errors. *** and ** denote significance at 1% and 5% levels, respectively. | Reference: Ray, S., Suganthi, D., Bhatia, S., & George, A. T. (2025). Spatial Inflation Convergence in India, mimeo |

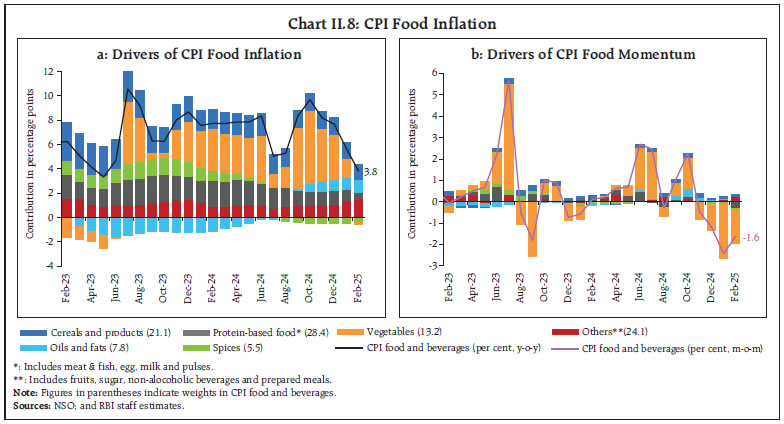

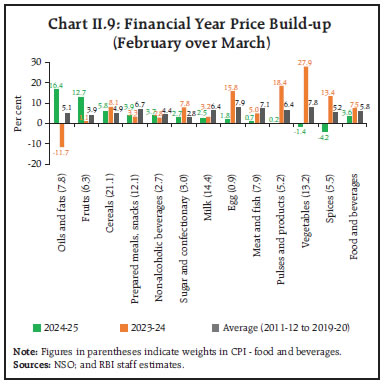

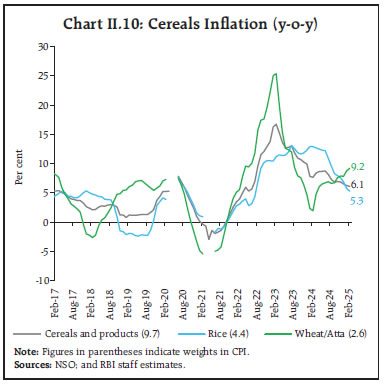

CPI diffusion indices (DIs)7 strengthened while remaining in the expansionary zone from September to December 2024. Following a dip in August, the headline CPI DI saw a steady sequential rise from September, largely driven by the goods subcomponent. Although remaining in the expansionary zone in January-February 2025, the headline CPI DI declined sharply, signalling a slowdown in incidence of price increases in the CPI basket. This moderation was primarily led by movements in CPI goods, while CPI services edged up (Chart II.6a). Threshold DIs8 – for price increases in excess of 4 per cent as well as 6 per cent on a month-on-month seasonally adjusted annualised rate (m-o-m saar) basis – continued to remain well below the 50-level mark, indicating that the extent of price increases across a majority of the CPI items continued to remain muted (Chart II.6b). II.2 Drivers of Inflation A historical decomposition of inflation using a vector autoregression (VAR)9 model indicates that the sharp moderation in inflation in Q4:2024-25 came from the reversal of supply side shocks seen in Q3 (Chart II.7a).  Goods inflation (with a weight of 76.6 per cent in overall CPI) contributed around 85 per cent of headline inflation, on average, between September 2024 and January 2025, and services (with a weight of 23.4 per cent) the remaining 15 per cent. In February 2025, however, the contribution of goods to overall inflation fell sharply to around 76 per cent following the large decline in CPI food inflation, while services contribution edged up (Chart II.7b). The contribution of perishable items (non-durable with a 7-day recall10) – which include vegetables, spices, fruits, and other food items such as milk, meat and fish, and prepared meals – jumped up in Q3:2024-25, contributing to the stickiness in headline inflation, before falling in January-February 2025. On the other hand, after the contribution of semi-perishables (non-durable goods with a 30-day recall) to overall inflation declined in Q3 – driven primarily by softening of inflation in pulses and sugar even as personal care items remained sticky – it started firming up again in January-February 2025. The contribution of durable items (goods with a 365- day recall) to overall inflation also edged up in January- February 2025 after remaining mostly steady during September-December 2024, reflecting the rising and elevated price inflation in gold and silver. The contribution of imported components11 to headline inflation registered a sequential increase since October and was at 21 per cent in February 2025 (a contribution of 0.8 percentage points to the headline inflation rate of 3.6 per cent) driven primarily by a pick-up in international prices of gold and silver, and the depreciation of the rupee (Chart II.7c). CPI Food Group Food and beverages (weight of 45.9 per cent in the CPI basket) group exhibited high volatility in H2:2024-25 of 2024-25 so far. The month of September witnessed a resurgence of price pressures, which got further accentuated in October. Tight supply of vegetables caused by adverse weather conditions, along with price pressures in oils and fats due to increased import duties on crude and refined edible oils combined with rising international prices, led to the surge in food inflation. Vegetable prices corrected sharply from November onwards with fresh crop arrivals and seasonal winter easing, which, along with easing of price pressures in pulses, led to a substantial softening of food inflation to 3.8 per cent by February 2025 (Chart II.8). The food price build-up in 2024-25 so far (up to February) has been significantly lower than last year and the historical levels. The drivers of food price build-up this year, however, have changed since last year. While oils and fats, fruits, prepared meals and non-alcoholic beverages registered a higher price build-up, those in pulses, cereals, sugar and eggs were noticeably lower than last year. In contrast to last year, spices and vegetable prices, on average, registered a substantial decline, although vegetables witnessed large intra-year price volatility. A softer price build-up was also observed in meat and fish, and milk (Chart II.9).  Cereals inflation (weight of 9.7 per cent in the CPI and 21.1 per cent in the food and beverages group) remained elevated, though it moderated from 6.9 per cent in October 2024 to 6.1 per cent in February 2025 (Chart II.10). This softening primarily came from rice due to improved supply conditions as reflected in higher production (6.7 per cent as per the second advance estimate (AE) 2024-25 over 2023-24) and higher mandi arrivals compared to the previous year, despite easing of export restrictions during September-October 2024. The comfortable buffer stocks of rice (8.7 times the norm as on March 16, 2025), along with the direct sale of rice to state governments, other government agencies, and continued retail sales, have aided in easing supply conditions and containing price pressures. Wheat inflation, on the other hand, hardened from 6.7 per cent in September 2024 to 9.2 per cent in February 2025 on tight supply conditions as reflected in lower mandi arrivals and low buffer stocks (0.9 times the norm as on March 16, 2025). In order to contain price pressures, supply management measures were implemented by the government, including the sale of 2.5 million tonnes of wheat through e-auctions under the Open Market Sale Scheme (OMSS) till March 2025 at a fixed reserve price, downward revision of the existing stock limit in December 2024 and further in February 2025, and continued restrictions on wheat exports. Second AE of 2024-25 agricultural production shows improved rabi wheat production (1.9 per cent increase over 2023-24).

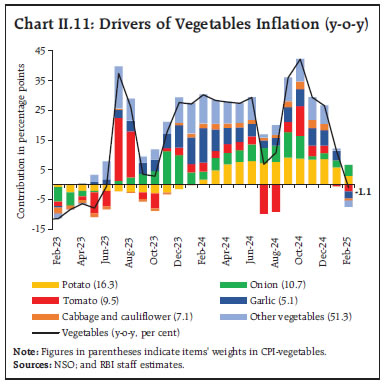

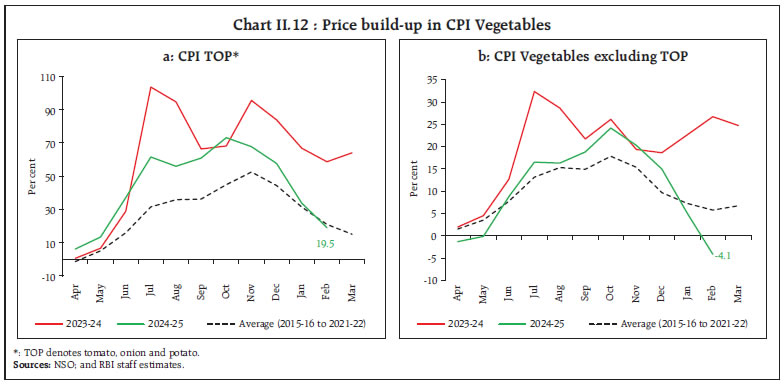

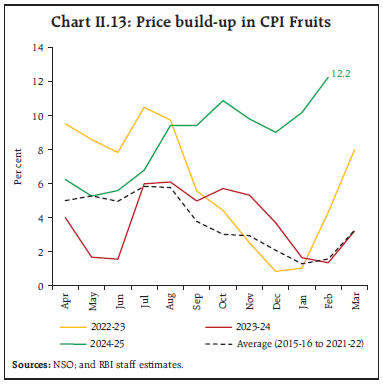

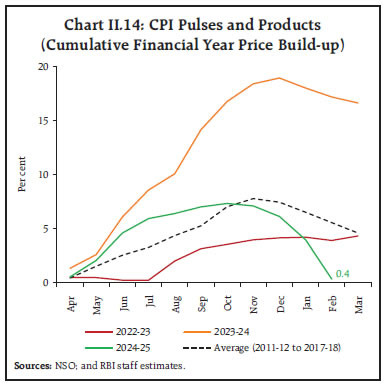

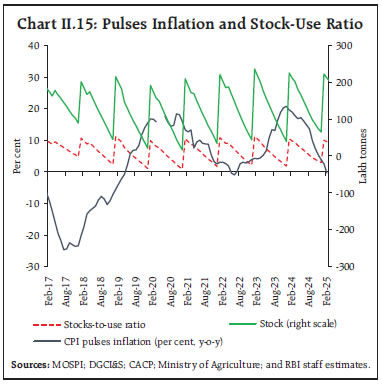

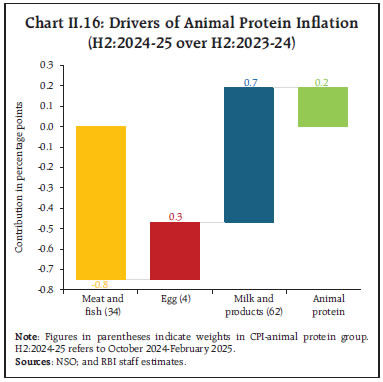

Vegetables (weight of 6.0 per cent in the CPI and 13.2 per cent in the food and beverages group) inflation reached a peak at 42.2 per cent in October 2024, induced by multiple and overlapping weather shocks, marking another year of volatile and elevated inflation. Thereafter, vegetables inflation declined sharply to (-)1.1 per cent by February 2025, aided by an unusually strong winter price correction during November 2024-February 2025 on account of robust production and fresh market arrivals (Chart II.11). Among key vegetables, potato prices increased (on y-o-y basis) by an average of around 66.2 per cent during September-December 2024 on account of lower production in 2023-24 [(-)5.0 per cent over 2022-23]. The steep price build-up due to lower production last year, however, was corrected subsequently in January- February 2025, with increased production for 2024-25 (4.4 per cent as per the first AE 2024-25 over 2023-24) and higher market arrivals. Onion price increases also moderated sharply on a y-o-y basis– to 30.4 per cent in February 2025 from 66.1 per cent in September 2024 – due to higher production (18.9 per cent as per the first AE 2024-25 over 2023-24) and increased late kharif arrivals even as export restrictions were relaxed. To contain price pressures, the government released onions from its buffer stocks through open market sales at a subsidised rate of ₹35 per kg across major consumption centres in September 2024. Furthermore, a special train, Kanda Express, was initiated in October 2024 for faster distribution from surplus to deficit states. Tomato prices, after increasing sharply by 161 per cent on a y-o-y basis in October 2024 from a deflation of (-)47.9 per cent in August 2024 on the back of lower mandi arrivals in southern states induced by unseasonal rainfall, corrected sharply recording a deflation of (-)28.5 per cent in February 2025 with improved supply.  Within vegatables excluding TOP (tomato, onion, and potato), garlic experienced persistently elevated inflation, averaging around 75 per cent during September-December 2024 due to modest production growth in 2023-24 (2.3 per cent over 2022-23, following a decline of (-)8.1 per cent in 2022-23 over 2021-22). Inflationary pressures in non-TOP vegetables, thereafter, eased by February 2025, led by a sharp moderation in garlic prices on the back of improved production (3.2 per cent growth as per the first AE 2024-25 over 2023-24). Consequently, the price build-up in both TOP and non-TOP categories remained higher than the historical pattern until December 2024. Thereafter, a sharp broad-based correction in vegetable prices resulted in a marked fall in the price build-up across TOP and non-TOP categories (Chart II.12).  Inflation in fruits (weight of 2.9 per cent in the CPI and 6.3 per cent within the food and beverages group) remained elevated since August 2024. In February 2025, it surged to 14.8 per cent, the highest print since October 2014, driven by a pick-up in price pressures, compounded by an unfavourable base effect. The price build-up in fruits this year has been substantially higher than last year and its historical trend (Chart II.13). The price pressures were primarily driven by coconut on the back of tight supply conditions attributed to lower production across major coconut-growing states, coupled with high festive demand. Since December 2024, apple prices have also hardened, reflecting declining imports towards the end of the apple marketing season in India. After moderating during September- December 2024, banana inflation increased sharply in February 2025, largely reflecting an unfavourable base effect. Groundnut prices, however, remained in deflation since August 2024 on account of higher kharif production (20.4 per cent as per the second AE 2024-25 over 2023-24).  Pulses, the primary source of plant-based protein (weight of 2.4 per cent in the CPI and 5.2 per cent in the food and beverages group), which registered double digit inflation during April-August 2024, witnessed sustained softening thereafter to (-)0.3 per cent in February 2025 on higher production (2.8 per cent for tur and 28 per cent for moong as per the second AE 2024-25 over 2023-24) and robust imports. Inflation in gram, however, remained elevated despite improved rabi production [4.5 per cent in 2024-25 as per the second AE over 2023-24 following (-)10.0 per cent in 2023-24 over 2022-23]. On the whole, the price build-up in pulses remained lower during April 2024-February 2025 as compared to the previous year, reflecting government interventions towards easing supply conditions through the retail sale of subsidised chana, moong and masur dals under the brand name Bharat dal and the extension of free import of yellow peas in stages till May 31, 2025, and tur till March 31, 2026 (Chart II.14). Relatedly, the stock-to-use ratio of 6.3 during September 2024-March 2025, in contrast to 5.9 over the same period in 2023-24, is indicative of improving supply conditions of pulses (Chart II.15).  Prices of animal-based protein items increased marginally during H2:2024-25, driven by milk and products, and eggs. On a y-o-y basis, price inflation in meat and fish (weight of 3.6 per cent in CPI and 7.9 per cent in CPI food and beverages group) increased sequentially to an average of 5.3 per cent during December 2024-January 2025 before moderating to 2.1 per cent in February 2025 on account of reduced demand for chicken due to bird flu in some states. Eggs (weight of 0.4 per cent in CPI and 0.9 per cent in the CPI food and beverages group) exhibited elevated and volatile price movements, from an average of 6.5 per cent during April-September 2024 to 4.8 per cent in November 2024 before increasing to 6.9 per cent in December on account of strong winter demand and increased feed costs. In January-February 2025, egg inflation moderated on account of a sharp correction in prices due to a mild winter and bird flu concerns that reduced demand, coupled with a favourable base effect. Inflation in milk and products (weight of 6.6 per cent in the CPI and 14.4 per cent within the food and beverages group) remained subdued at around 2.9 per cent during September 2024-February 2025 on account of lower input costs (Chart II.16).

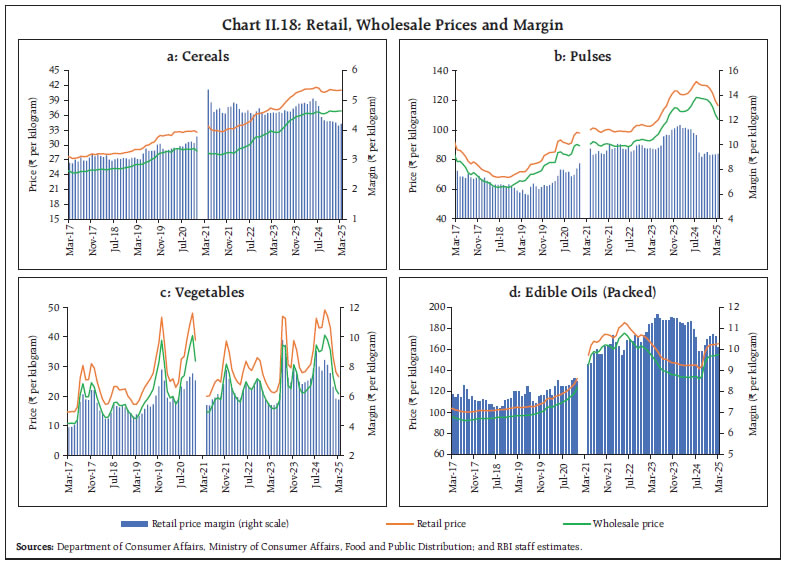

After recording 19 consecutive months of deflation, oils and fats (weight of 3.6 per cent in the CPI and 7.8 per cent within the food and beverages group) price inflation increased from 2.5 per cent in September 2024 to 16.4 per cent by February 2025. The sharp pick-up in edible oil prices was triggered by a hike in basic customs duty on crude and refined edible oils by 20 percentage points in September 2024, along with an uptick in international edible oil prices. On a month-on-month basis, however, the rate of price increases has softened since November 2024, reflecting improved supply conditions on account of higher domestic production of oilseeds (8.4 per cent as per the second AE 2024-25 over 2023-24) and easing of global edible oil prices (Chart II.17). Within the oils and fats sub-group, ghee and butter price inflation remained broadly moderate, indicative of the transmission of lower milk inflation. Sugar and confectionery (weight of 1.4 per cent in the CPI and 3.0 per cent in the food and beverages group) inflation moderated in 2024-25 so far on the back of higher stocks and fresh arrivals during the cane crushing season. However, lower estimated kharif production [(-)4.0 per cent as per the second AE 2024-25 over 2023-24] and partial removal of export restrictions, along with removal of restrictions on sugar diversion for ethanol production in August 2024, pose upward risks to sugar prices. Among other food items, deflation in spices deepened from (-)1.4 per cent in July 2024 to an average of (-)7.4 per cent during November and December 2024, primarily driven by jeera and dry chillies, before narrowing to (-)5.8 per cent in February 2025. Inflation in prices of prepared meals has witnessed a sequential pick-up in H2 so far, though it remains contained. Retail Margins The absolute retail price margins, defined as the difference between retail and wholesale prices12 in the case of cereals, remained steady during October 2024-January 2025 before witnessing a marginal deceleration in February-March 2025, reaching ₹4.2 per kg, the lowest since December 2020. Retail price margins of pulses edged up during October-November 2024 but thereafter declined, hovering around ₹9.2 per kg till February 2025 before a marginal uptick to ₹9.3 per kg in March 2025. The retail price margins of edible oils witnessed a gradual uptick during October 2024-February 2025 due to firming up in the margins of all edible oils – soybean, sunflower, mustard, and refined oils. Thereafter, retail margins declined to ₹10.1 per kg in March 2025, with moderation in retail and wholesale prices of edible oils. In case of TOP vegetables, retail price margins registered a sequential decline since October 2024 and reached ₹5.7 per kg in March 2025, primarily driven by tomato and potato (Chart II.18).  Sectoral and Spatial Distribution of Food Inflation The CPI food inflation pressures eased across both rural and urban areas since November 2024 with urban food inflation decreasing more than rural food inflation (Chart II.19).

| Table II.1: Distribution of food inflation across States/UTs: Number of states# | | Food Inflation Range | 2023-24 (Apr-Feb) | 2024-25 (Apr-Feb) | | Less than 2 per cent | 1 | 1 | | Between 2 to 4 per cent | 4 | 0 | | Between 4 to 6 per cent | 11 | 12 | | Greater than 6 per cent | 20 | 23 | #Accounted for the unification of Daman and Diu with Dadra & Nagar Haveli and the formation of Ladakh as a Union Territory (UT).

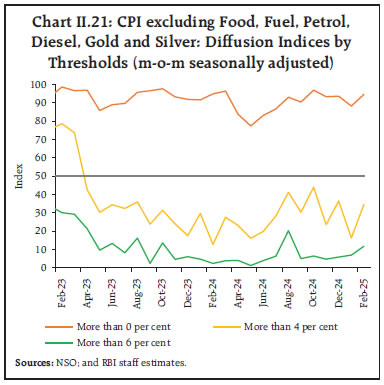

Sources: NSO; and RBI staff estimates. | Food inflation pressures during April 2024-February 2025 seem to have strengthened spatially, with the number of states/UTs experiencing food inflation above 6.0 per cent on an average rising to 23 vis-à-vis 20 in the corresponding period a year ago. Sequentially, however, there has been a considerable softening in food inflation pressures across states, with the number of states experiencing food inflation in excess of 6.0 per cent reducing significantly – from a peak of 32 states in November 2024 to 05 states in February 2025 (Table II.1). CPI Fuel Group CPI fuel remained in deflation in H2:2024-25 so far, although the deflation moderated sharply from (-)5.3 per cent in August 2024 to an average of (-)1.5 per cent during September 2024-February 2025. Softer deflation in LPG due to unfavourable base effects, and that of kerosene due to a sharp pickup in price momentum in December, along with a pick-up in firewood and chips prices on a y-o-y basis, led to the narrowing of deflation in CPI fuel in H2. The movement of domestic kerosene prices largely mirrored international price movements. Domestic retail prices of LPG, however, remained unchanged during H2, despite a pick-up in international prices, contributing to its continuing deflation. Electricity prices, on a y-o-y basis, moved in a range-bound manner – rising to 5.4 per cent in September-October from 4.9 per cent in August – before edging down to 5.3 per cent in February 2025 (Chart II.20). Core CPI (CPI excluding Food and Fuel) Core inflation (CPI excluding food and fuel) edged up from a low of 3.3 per cent in August 2024 to 3.8 per cent in October and remained steady around 3.6 - 3.7 per cent during November 2024-January 2025. In February 2025, core inflation picked-up to 4.1 per cent – the highest print in 15 months – driven primarily by a sharp increase in gold prices. Exclusion-based measures of underlying inflation, which remove volatile items such as petrol and diesel, gold and silver in addition to food and fuel, also remained muted till January before witnessing a notable uptick in February, though of a lower magnitude (Table II.2). Exclusion-based CPI threshold DIs during September 2024-February 2025 point to the continuation of muted price pressures across the core CPI basket. CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol, diesel, gold and silver DI for price increases of greater than 4 per cent (m-o-m saar) remained in the contraction zone throughout H2, indicating that a majority of items exhibited price increases at a m-o-m saar of less than 4 per cent. The DI for price increases of greater than 6 per cent (m-o-m saar) also remained deep in the contractionary zone during September 2024-February 2025, indicating that most of the items in CPI core exhibited price increases below the 6 per cent m-o-m saar threshold during this period (Chart II.21). Though still in contraction zone, the month of February saw a notable uptick in threshold DIs. | Table II.2: Exclusion-based Measures of Inflation (y-o-y) | | Period | CPI excluding food and fuel (47.3) | CPI excluding food fuel petrol diesel (45.0) | CPI excluding food fuel petrol diesel gold silver (43.8) | | Jan-24 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.4 | | Feb-24 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | | Mar-24 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | | Apr-24 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.0 | | May-24 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.8 | | Jun-24 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.8 | | Jul-24 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.1 | | Aug-24 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.0 | | Sep-24 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.2 | | Oct-24 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.3 | | Nov-24 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.3 | | Dec-24 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.3 | | Jan-25 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.2 | | Feb-25 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.4 | Notes: 1. Figures in parentheses indicate weights in CPI.

2. Derived as residual from headline CPI.

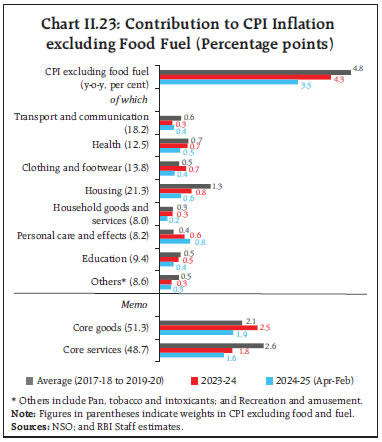

Sources: NSO; and RBI staff estimates. | Core inflation across April 2024-February 2025 exhibited some signs of higher inflation variability when compared to the previous year, but the level of inflation and its variability were much lower than other post-COVID years (Chart II.22). Core inflation pressures in 2024-25 so far, on an average, were muted and broad-based, covering both core goods and services categories. Contribution of all sub-groups/ groups (barring transport and communication, and personal care and effects) were lower compared to previous years and pre-COVID patterns (Chart II.23).

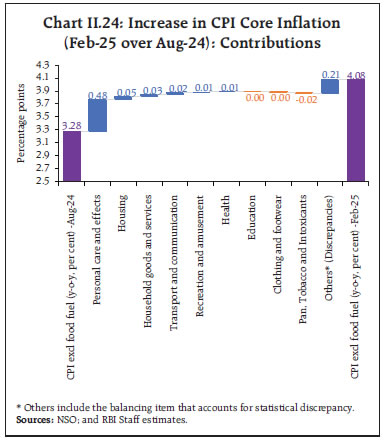

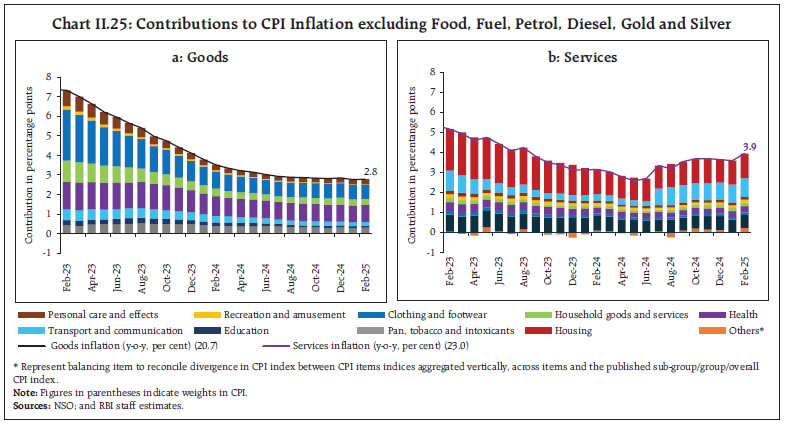

The pick-up in core inflation between August 2024 and February 2025 was largely contributed by the personal care and effects sub-group reflecting the spike in gold and silver prices. Notably, a significant portion of the increase also stemmed from the balancing item that accounts for statistical discrepancy13. Adjusted for the pick-up in gold and silver prices, and statistical discrepancies, the increase in core inflation has been low, with the modest contribution of housing, household goods and services, transport and communication, recreation and amusement, and health, somewhat offset by the decline in contribution of education, pan, tobacco and intoxicants and clothing and footwear to overall core inflation (Chart II.24). Goods inflation arrived at by decomposing CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol, diesel, gold, and silver inflation into its goods (with a weight of 20.7 per cent in the headline CPI) and services (weight of 23.0 per cent) components, remained broadly steady in H2 so far (up to February 2025), albeit showing a marginal softening from 2.9 per cent in August-September 2024 to 2.8 per cent in October 2024, where it remained steady at that level till February 2025. The contribution of all sub-groups was also unchanged during this period (Chart II.25a). Core services inflation firmed up from 3.4 per cent in August 2024 to 3.7 per cent in February 2025. A significant part of the increase can be attributed to statistical aggregation effects14. Abstracting this, the pick-up in core services inflation was primarily driven by housing (house rent, residential building and land, water charges), health, household and transport and communication services (Chart II.25b).

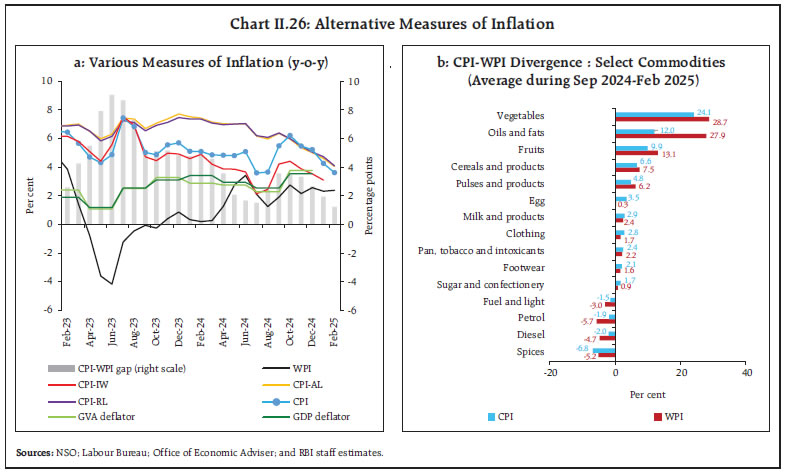

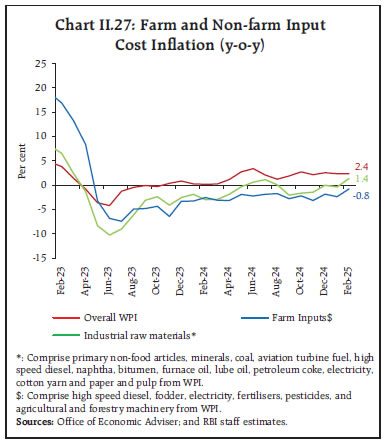

Trimmed mean measures15 of inflation remained muted in H2. While there were variations across months, all trimmed mean measures of inflation gradually softened from October 2024 to February 2025 (Table II.3). Other Measures of Inflation CPI inflation for agricultural labourers (CPI-AL) and rural labourers (CPI-RL) registered sequential moderation since September 2024. Moreover, the gap between CPI-AL (and RL) with respect to CPI headline inflation narrowed vis-à-vis last year on significant moderation in food inflation in both CPI-AL and RL. CPI inflation for industrial workers (CPI-IW), on the other hand, was below the headline CPI inflation during the same period, primarily due to lower food inflation and steeper fuel deflation in CPI-IW vis-à-vis headline CPI. Wholesale price index (WPI) inflation, year-on-year, accelerated to 2.8 per cent in October 2024, with food inflation touching a record peak of 12.1 per cent in more than a decade. Thereafter, following the moderation in food inflation, WPI inflation softened to 2.2 per cent in November. After registering an uptick to 2.6 per cent in December, WPI inflation has since then moderated and remained within a narrow range of 2.3 to 2.4 per cent during January-February 2025, as the softening in food inflation was offset by a pick-up in non-food manufactured products inflation and a narrowing of deflation in the fuel group. With overall WPI recording a pick-up during Q3:2024-25, inflation measured by deflators for gross value added (GVA) and gross domestic product (GDP) picked up. GDP deflator rose to 3.5 per cent in Q3 from 2.5 per cent in Q2 and GVA deflator rose to 3.8 per cent in Q3 from 2.3 per cent in Q2 (Chart II.26a). | Table II.3: Trimmed Mean Measures of Inflation (y-o-y) | | Month | 5% trimmed | 10% trimmed | 25% trimmed | Weighted Median | | Jan-24 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 3.7 | | Feb-24 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.6 | | Mar-24 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 3.3 | | Apr-24 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | | May-24 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 2.9 | | Jun-24 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 2.9 | | Jul-24 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.0 | | Aug-24 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.0 | | Sep-24 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.0 | | Oct-24 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.0 | | Nov-24 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.2 | | Dec-24 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.1 | | Jan-25 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.9 | | Feb-25 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 2.9 | | Sources: NSO; and RBI staff estimates. | Similar sub-groups/items across CPI and WPI also exhibited diverse inflation movements. While WPI inflation in food sub-groups such as cereals, pulses, fruits, oils and fats, and vegetables ruled above corresponding CPI groups/subgroups, those in sugar, milk and egg prices were higher in the CPI than in the WPI. Similarly, inflation in clothing, and pan, tobacco and intoxicants was higher in the CPI measure vis-à-vis the WPI. On the other hand, fuel and light recorded a deflation in both CPI and WPI, with CPI showing a lower rate of decline. Likewise, petrol and diesel recorded a lower rate of deflation in the CPI vis-a-vis WPI (Chart II.26b). II.3 Costs Costs, as measured by WPI inflation in industrial raw materials and farm inputs, stayed largely in deflation since September 2024, primarily on account of electricity, fodder, aviation turbine fuel (ATF), high-speed diesel (HSD), and pesticides driven by easing international commodity prices (Chart II.27). The other contributory factors were non-food articles – particularly raw cotton and oilseeds – whose prices were mostly in deflation during this period. Mineral oils also remained in deflation, driven majorly by HSD, ATF, kerosene and petrol. In February 2025, however, industrial input costs increased and deflation in farm input costs decelerated with an increase in prices of furnace oil, naphtha, and paper and pulp products in the industrial sector and higher fodder and machinery costs in the agricultural sector. Minerals inflation, on the other hand, remained positive in H2:2045-25, primarily led by iron ore due to an increase in global iron ore prices on the back of higher Chinese demand and lower supply.

Nominal rural wage growth averaged 6.3 per cent during October 2024-February 2025. While agricultural sector wages saw a sequential pick-up during this period, non-agricultural sector wage growth showed a deceleration (Chart II.28). Agricultural wage growth was mainly driven by horticulture workers, inland fishermen, picking workers, and ploughing and tilling workers; while that of non-agricultural wages was on account of plumbers, electricians, and LMV and tractor drivers in the rural sector.

In the organised sector, staff cost growth (y-o-y) decelerated for manufacturing and services sectors in Q3:2024-25 as compared to the previous quarter, driven by a decline in momentum of staff costs in both sectors assisted by favourable base effects (Chart II.29). On the assessment and outlook of cost conditions, manufacturing firms polled in the Reserve Bank’s enterprise surveys16 indicate that input cost pressures may soften in Q1:2025-26 but pressures from salary outgo are expected to accelerate. Manufacturing firms also anticipate growth of selling prices to decelerate in Q1 in tandem with lower input costs whereas for services firms, the input and wage cost pressures as well as selling prices are likely to pick up during Q1:2025-26. Infrastructure firms, on the other hand, expect input cost and wage cost pressures to rise further along with higher growth in selling prices in Q1:2025-26 (Chart II.30). One year ahead business inflation expectations17, after firming up to 4.79 per cent in December 2024 from 4.18 per cent in November, corrected sharply to 4.24 per cent in January 2025 and softened further to 4.06 per cent in February 2025. The businesses polled in the survey perceived marginal softening in cost pressures. However, subdued sales figures resulted in muted expectations for profit margins compared to the previous round. Manufacturing firms polled for the purchasing managers’ index (PMI) reported an uptick in input prices in Mar-25 after three months of consecutive deceleration. Manufacturing sector saw a slowdown in the rate of increase in output prices, during December 2024 to March 2025, though it continued to grow at a faster pace as compared to input costs. On the other hand, PMI services sector continued to report relatively sticky input prices in March 2025. The input-output price gap for the manufacturing sector indicates no pent-up pass-through with output price increase remaining sticky since October 2024, while the increase in prices charged by the services sector remained softer vis-à-vis that of input prices from September 2024 (Chart II.31). II.4 Conclusion CPI headline inflation exhibited significant volatility in H2:2024-25 due to food price shocks. Despite repetitive supply side shocks, pre-emptive monetary policy actions have helped to limit their second-round effects on underlying inflation trends and sustain the disinflation process. In this context, supply side measures have also played a role in mitigating the impact of sectoral price shocks on general inflation trends. The significant softening in CPI headline inflation in Q4:2024-25 so far, driven by the sharp correction in food inflation, is likely to sustain on robust agricultural production. In the absence of further adverse weather events and negative spillovers from geopolitical and external sector uncertainties, this could facilitate a durable alignment of headline inflation with the 4 per cent target and anchor inflation expectations effectively, thereby enhancing the credibility of monetary policy. The impact of the hike in trade tariffs by the US on domestic inflation outlook is uncertain at the moment. Following the tariff announcements, commodity prices, however, have seen sharp swings – while energy and metal prices plunged, gold prices experienced considerable volatility. Amidst large uncertainties surrounding the global economic outlook, the considerable progress achieved on the disinflation front has provided greater leeway to monetary policy in effectively managing the growth-inflation balance. _________________________________________________________________________________

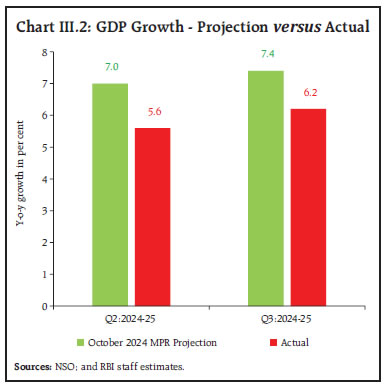

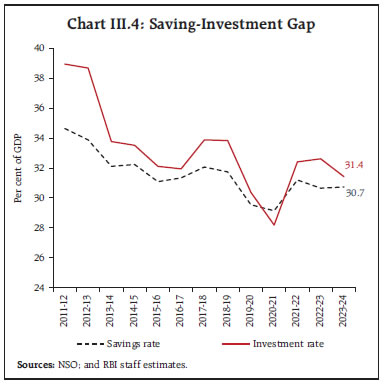

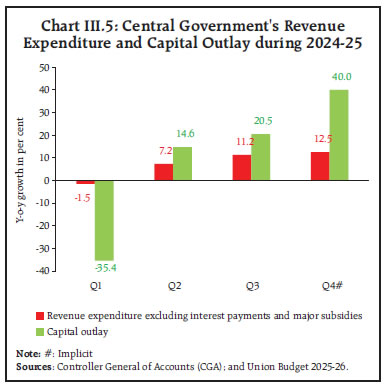

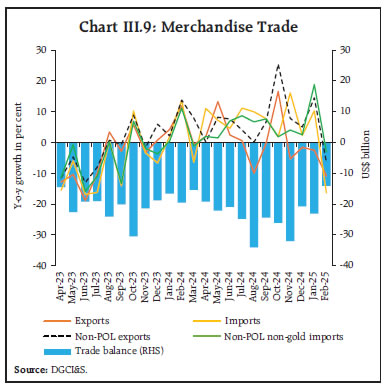

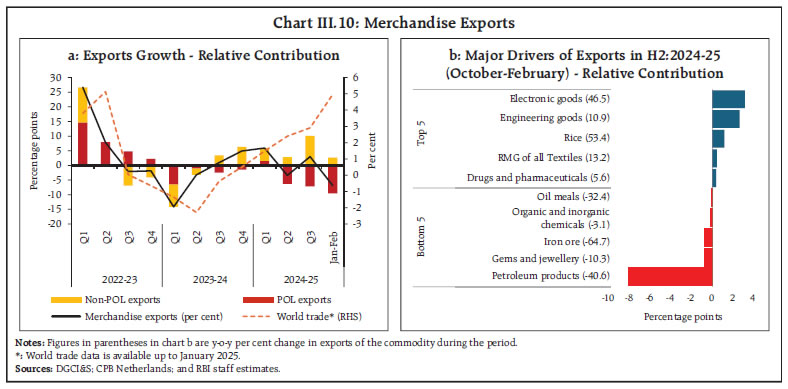

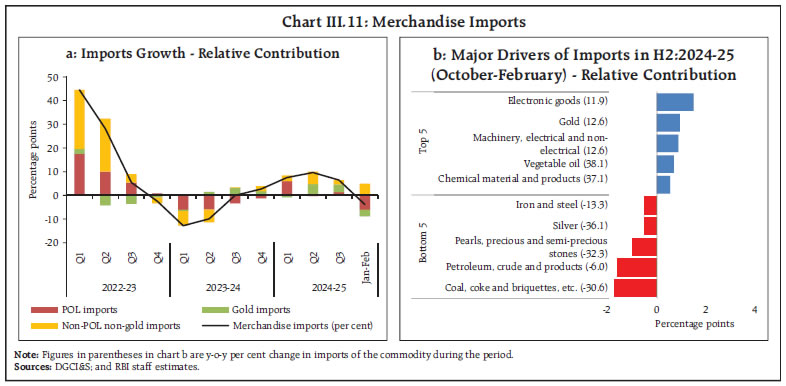

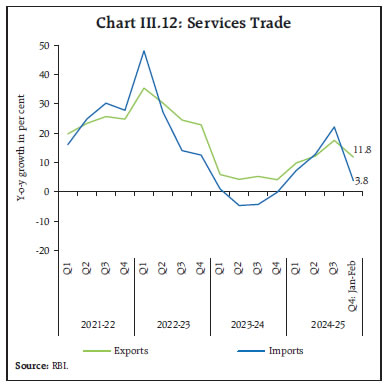

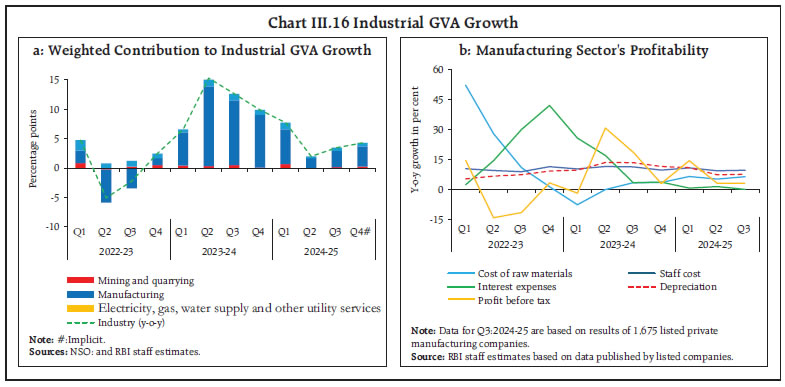

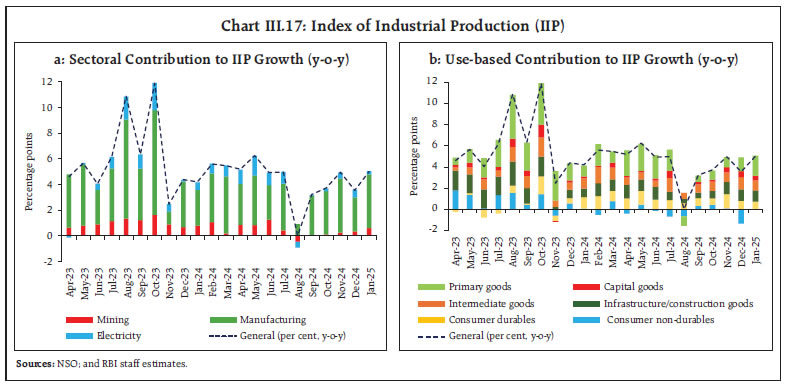

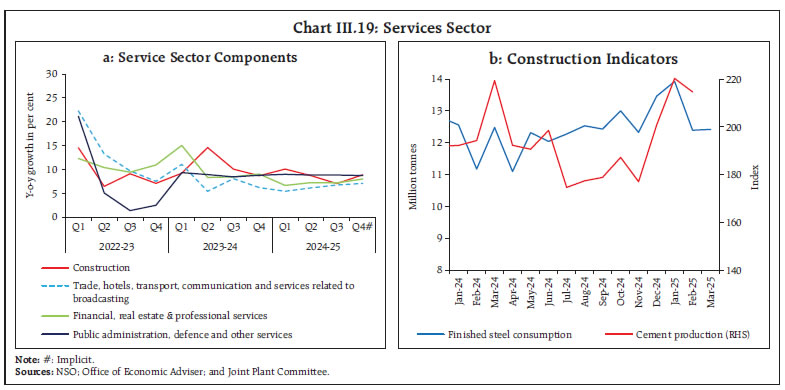

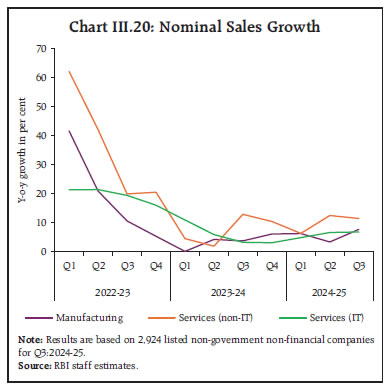

III. Demand and Output Domestic economic activity recovered in H2:2024-25 from Q2:2024-25, with consumption demand acting as the main driver. Improved prospects for agriculture and rural economy, sustained buoyancy in services, government’s efforts to spur demand, and healthy balance sheets of banks and corporates brighten the outlook. The recent tariff announcements by the US, on the other hand, is likely to adversely impact India's net external demand. Heightened trade policy uncertainties, geoeconomic fragmentations, geopolitical tensions, volatility in global financial markets and weather disturbances pose downside risks to the domestic growth outlook. Domestic economic activity picked up in H2:2024-25 after slackening in Q2. Private consumption remained robust, driven by strong rural demand and improving urban demand, and government final consumption expenditure picked up in H2. Investment activity moderated vis-a-vis the highs of the previous years. Net external demand remained bouyant supported by resilient services exports. On the supply side, while agriculture posted a strong growth and services remained resilient, industrial growth was muted, on the back of deceleration in manufacturing activity. III.1 Aggregate Demand Aggregate demand conditions recovered as real gross domestic product (GDP) growth improved to 6.2 per cent (y-o-y)1 in Q3:2024-25 from 5.6 per cent in the previous quarter (Table III.1 and Chart III.1a). The momentum of GDP – quarter-on-quarter (q-o-q) seasonally adjusted annualised rate (SAAR) – also recorded improvement as compared to the previous quarter (Chart III.1b). GDP Projections versus Actual Outcomes The Monetary Policy Report (MPR) of October 2024 had projected real GDP growth at 7.0 per cent for Q2, and 7.4 per cent for both Q3 and Q4 of 2024-25. Actual growth in Q2 and Q3 turned out to be much lower (Chart III.2), mainly on account of moderation in investment on the back of lower government capital expenditure. Data for Q4 are scheduled to be released by the National Statistical Office (NSO) on May 30, 2025. | Table III.1: Real GDP Growth | | (Y-o-y, per cent) | | Item | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | Weighted Contribution* | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | | (FRE) | (SAE) | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4# | | Private Final Consumption Expenditure | 5.6 | 7.6 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 7.7 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 9.9 | | Government Final Consumption Expenditure | 8.1 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 5.3 | 20.1 | 2.3 | 6.6 | -0.5 | 3.8 | 8.3 | 4.2 | | Gross Fixed Capital Formation | 8.8 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 8.4 | 11.7 | 9.3 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.4 | | Exports | 2.2 | 7.1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | -7.0 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 2.5 | 10.4 | 7.6 | | Imports | 13.8 | -1.1 | 3.3 | -0.3 | 18.0 | 14.3 | 11.3 | 11.4 | -0.7 | -2.5 | -1.1 | -0.1 | | GDP at market prices | 9.2 | 6.5 | 9.2 | 6.5 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 7.6 | Notes: *: Component-wise contributions to growth do not add up to GDP growth because changes in stocks, valuables and discrepancies are not included.

FRE: First revised estimates; SAE: Second advance estimates. #: Implicit

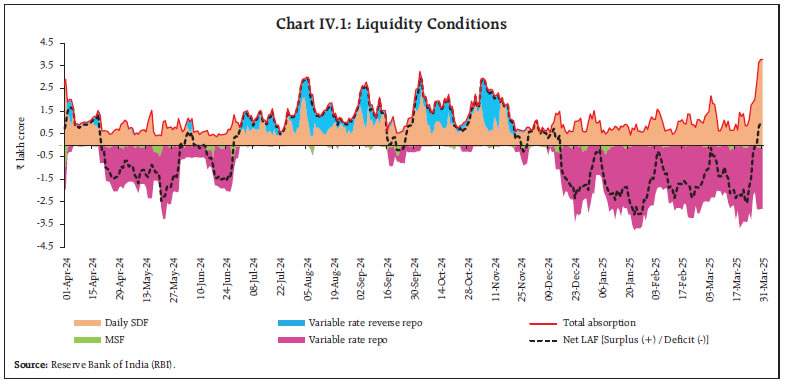

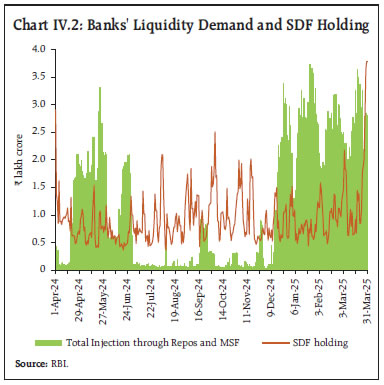

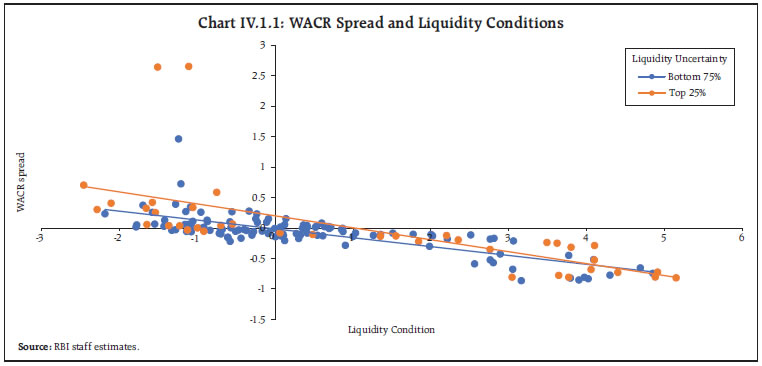

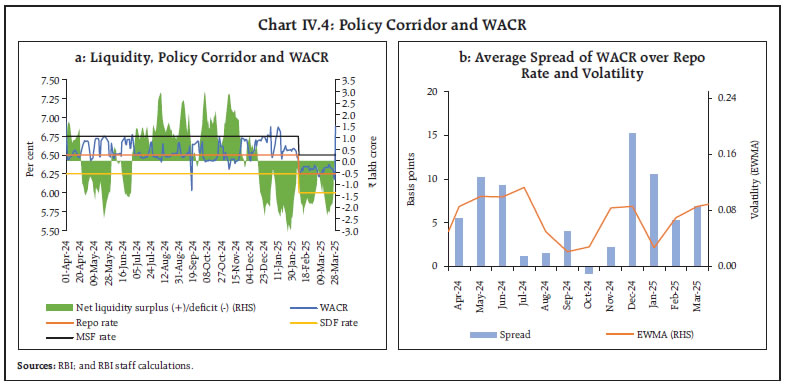

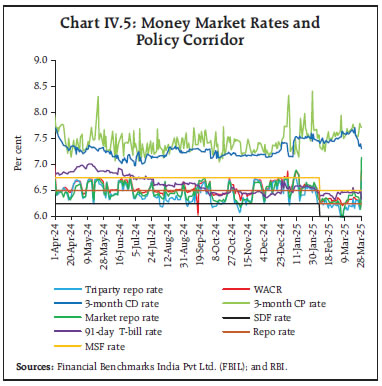

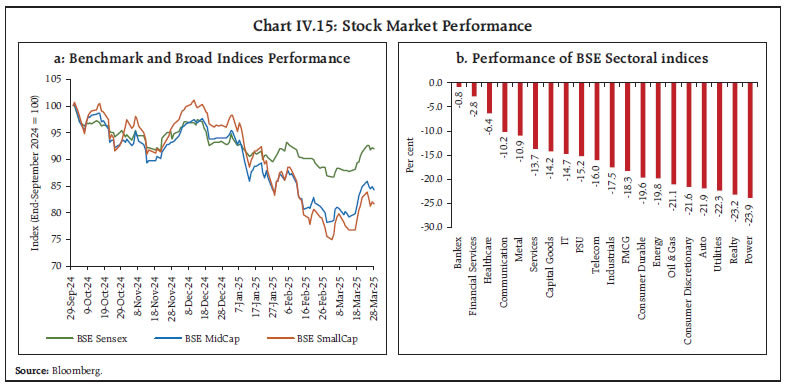

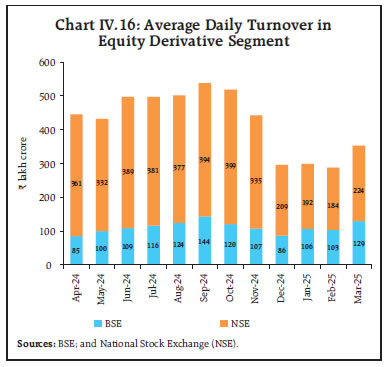

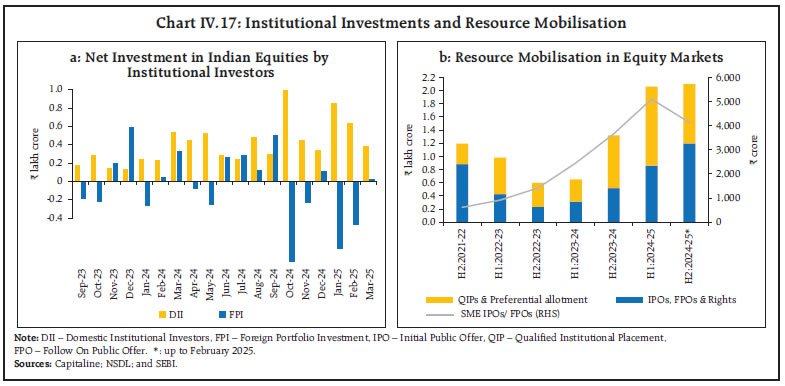

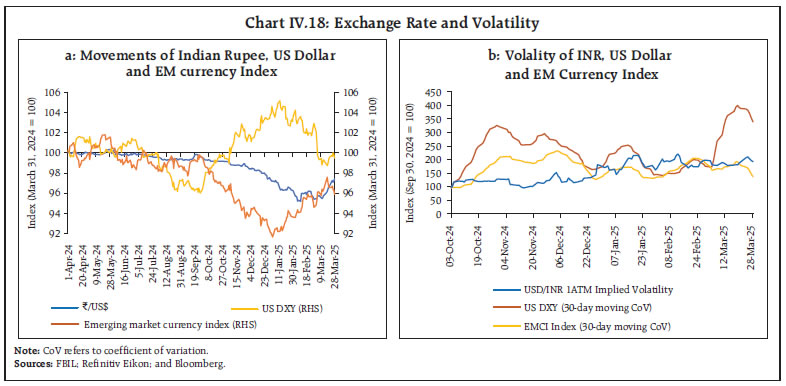

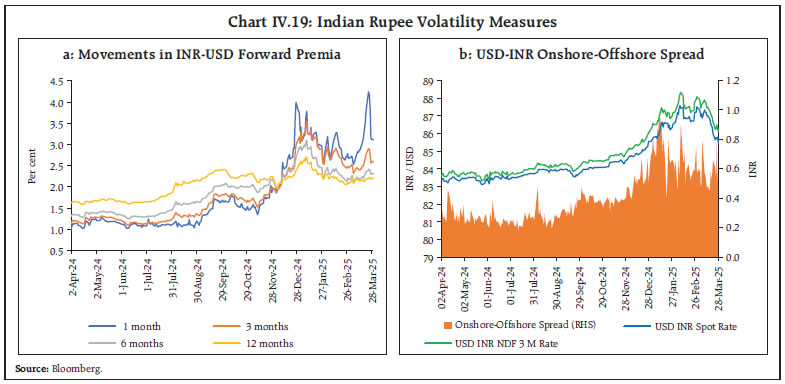

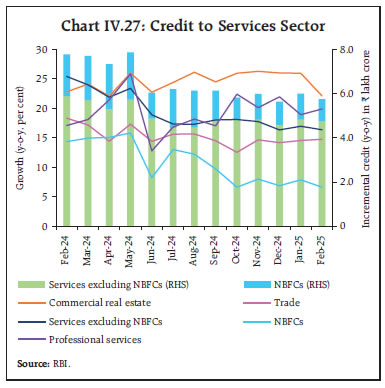

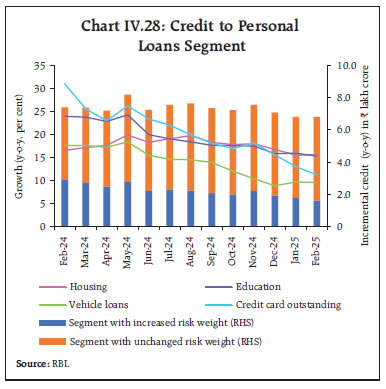

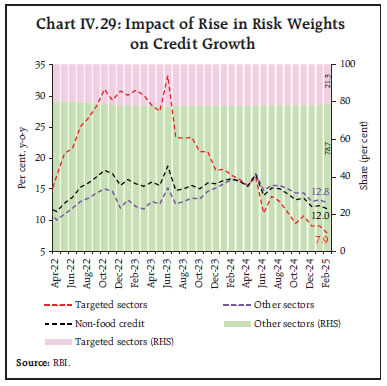

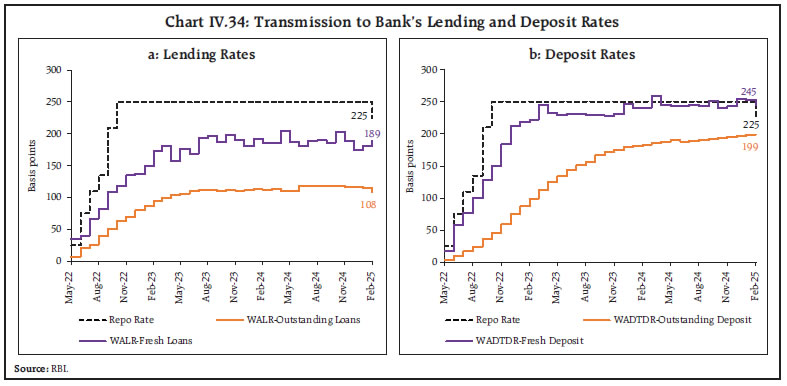

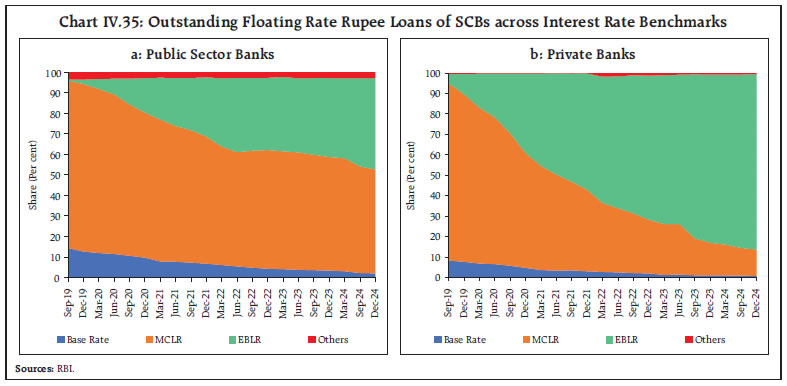

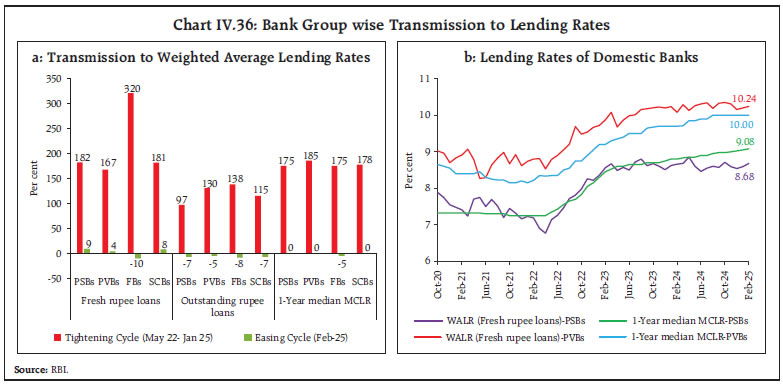

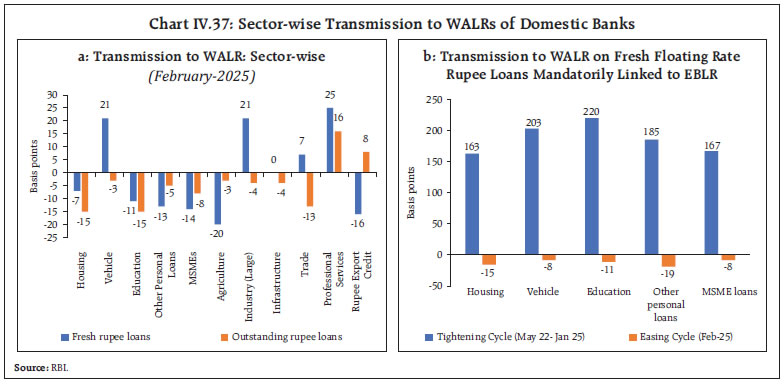

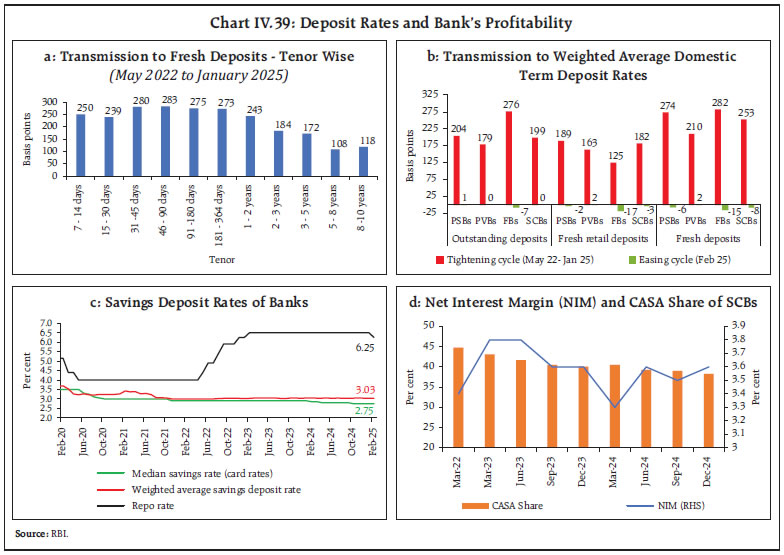

Sources: National Statistical Office (NSO); and RBI staff estimates. |