Jeevan Kumar Khundrakpam

Sitikantha Pattanaik*

Contagion from the global crisis necessitated use of fiscal stimulus measures in India

during 2008-10 in order to contain a major slowdown in economic growth. Given the usual

downward inflexibility of fiscal deficit once it reaches a high level, as has been experienced

by India in the past, there could be medium-term implications for the future Inflation path,

which must be recognised while designing the timing and speed of fiscal exit. Inflation, at

times, may become effectively a fiscal phenomenon, since the fiscal stance could influence

significantly the overall monetary conditions. As highlighted in this paper, fiscal deficit

could be seen to influence the Inflation process either through growth of base money created

by the RBI (i.e. net RBI credit to the Government) or through higher aggregate demand

associated with an expansionary fiscal stance (which could increase growth in broad

money). Empirical estimates of this paper conducted over the sample period 1953-2009

suggest that one percentage point increase in the level of the fiscal deficit could cause about

a quarter of a percentage point increase in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI). The paper

emphasises that the potential Inflation risk should work as an important motivating factor

to ensure a faster return to the fiscal consolidation path in India, driven by quality of

adjustment with appropriate rationalisation of expenditure, rather than waiting for revenue

buoyancy associated with sustained robust growth to do the job automatically. The

importance of fiscal space in the India specific context needs to be seen in terms of not only

the usual output stabilisation role of fiscal policy but also the occasional need for use of

fiscal measures to contain such Inflationary pressures that may arise from temporary but

large supply shocks.

JEL Classification : B21, E31, E62.

Keywords : Crisis, Fiscal, Inflation.

Introduction

Fiscal stimulus emerged as the key universal instrument of hope in

almost every country around the world, when the financial crisis in the

advanced economies snowballed into a synchronised global recession.

Borrowing as much at as low a cost as possible to stimulate the sinking

economies necessitated unprecedented coordination between the fiscal

and monetary authorities. It is the fiscal stance of the Governments

that had to be accommodated without any resistance by the monetary

authorities so as to minimise the adverse effects of the crisis on output

and employment, while also saving the financial system from a complete

breakdown. Given the deflation concerns in most countries –rather than

the fear of Inflation – monetary authorities had no reasons to resist. The

universal resort to fiscal stimulus, however, has now led to significant

increase in deficit and debt levels of the advanced economies, which

may operate as a permanent drag for some time, vitiating the overall

macroeconomic outlook, including Inflation. OECD projections indicate

that OECD level fiscal deficit may reach 60 year high of about 8 per

cent of GDP in 2010, and public debt may exceed 100 per cent of GDP

in 2011, which will be 30 percentage points higher than the comparable

pre-crisis levels in 2007. In the process of managing the financial crisis,

fiscal imbalances have been allowed to reach levels that could trigger

fiscal crisis in several countries. The market perception of sovereign

risk has changed significantly in 2010, particularly since the time that

the fiscal crisis in Greece has surfaced and contaminated the Euro-area.

The same private sector that was bailed out at the cost of fiscal excesses

will now perceive Government papers as risky and fiscal imbalances as

the harbinger of the next crisis.

In India, the fiscal response to the global crisis was swift and

significant, even though India clearly avoided a financial crisis at home

and also continued to be one of the fastest growing economies in the

World in a phase of deep global recession. Despite the absence of any

need to bailout the financial system, it is the necessity to partly offset the

impact of deceleration in private consumption and investment demand

on economic growth, which warranted adoption of an expansionary fiscal

stance. One important consequence of this, though, was the significant deviation from the fiscal consolidation path, and the resultant increase

in the fiscal deficit levels over two consecutive years (2008-10).

The immediate impact of the higher levels of fiscal deficit on

Inflation in India could be seen as almost negligible, since: (a) the

expansionary fiscal stance was only a partial offset for the deceleration

in private consumption and investment demand, as the output-gap

largely remained negative, indicating no risk to Inflation in the nearterm;

and (b) despite large increase in the borrowing programme of

the Government to finance the deficit, there was no corresponding

large expansion in money growth, since demand for credit from the

private sector remained depressed. Thus, neither aggregate demand

nor monetary expansion associated with larger fiscal deficits posed any

immediate concern on the Inflation front. The usual rigidity of deficit

to correct from high levels to more sustainable levels in the near-term,

however, entails potential risks for the future Inflation path of India,

which may become visible when the demand for credit from the private

sector reverts to normal levels and if the revival in capital flows turns

into a surge again over a sustained period, that may require sterilised

intervention. The major risk to future Inflation would arise from how

the extra debt servicing could be financed while returning to sustainable

levels through planned consolidation. Revenue buoyancy associated

with the recovery in economic activities to a durable high growth path

would only contribute one part; the major important part, however, has

to come either from a combination of higher taxes, withdrawal of tax

concessions and moderation in public expenditure, which could weaken

growth impulses or from higher Inflation tax, suggesting higher money

growth and associated pressure on future Inflation.

Conceptually, the risk to Inflation from high fiscal deficit arises

when fiscal stimulus is used to prop up consumption demand, rather

than to create income yielding assets through appropriate investment,

which could have serviced the repayment obligations arising from

larger debt. As highlighted by Cochrane (2009) in the context of the

US, “...If the debt corresponds to good quality assets, that are easy...If

the new debt was spent or given away, we’re in more trouble. If the debt

will be paid off by higher future tax rates, the economy can be set up for a decade or more of high-tax and low-growth stagnation. If the Fed’s

kitty and the Treasury’s taxing power or spending-reduction ability are

gone, then we are set up for Inflation.” It may be worth recognising that

all over the world, at some stage, the risk of active anti-Inflationary

policy conflicting with inflexible fiscal exit cannot be ruled out. As

highlighted by Davig and Leeper (2009) in this context for the US,

“...as Inflation rises due to the fiscal stimulus, the Federal Reserve

combats Inflation by switching to an active stance, but fiscal policy

continues to be active....In this scenario, output, consumption and

Inflation are chronically higher, while debt explodes and real interest

rates decline dramatically and persistently”.

The future risks to Inflation in India from fiscal stimulus, thus could

arise from the downward inflexibility of the deficit levels, and with

revival in demand for credit from the private sector and consolidation

of growth around the potential, the fiscal constraint could be manifested

in the form of pressures on both aggregate demand and money supply.

Surges in capital flows could complicate the situation further. This paper

recognises the possible policy challenge arising from higher money

growth on account of persistent fiscal constraint, revival in private credit

demand and surges in capital flows, on the one hand, and higher policy

interest rate chasing higher Inflation on the other. Possible crowding-out

effects associated with the fiscal constraint may also lead to a situation

where high Inflation and high nominal interest rates co-exist. Since

much of these possibilities could be empirically validated over time

depending on what outcome actually may materialise in the future, this

paper not only recognises the potential risks to the future Inflation path,

but also aims at unravelling the relevance of the perception by studying

the relationship between fiscal deficit and Inflation in India over the

sample period 1953 to 2009.

Macroeconomic variables are generally interrelated in a complex

manner. Therefore, a deeper understanding of Inflation dynamics would

involve analysing its relationship with macroeconomic variables such

as deficit, money supply, public debt, external balance, exchange rate,

output gap, global Inflation and commodity prices, and interest rates.

In the literature, particularly in the developing country context, simple models are, however, often used to analyse the Inflationary impact of

fiscal deficit. This largely reflects the role of fiscal dominance, which

has often been a phenomenon in many developing countries. Thus,

fiscal-based theories of Inflation are more common in the literature of

developing countries (for example, Aghevli and Khan (1978), Alesina

and Drazen (1978) and Calvo and Vegh (1999)). On the other hand, for

developed countries, fiscal policy is often considered to be unimportant

for Inflation determination, at least on theoretical grounds, as the desire

to obtain seigniorage revenue plays no obvious role in the choice of

monetary policy (Woodford, 2001).

In the Indian context also, there are several studies analysing the

nexus between government deficits, money supply and Inflation. The

findings of these studies generally point to a self perpetuating process

of deficit-induced Inflation and Inflation-induced deficit, besides the

overall indication that government deficits represent an important

determinant of Inflation (for example, Sarma (1982), Jhadav (1994) and

Rangarajan and Mohanty (1998)). The above results have been on the

expected lines given that till the complete phasing out of the ad hoc

treasury bills in 1997-98, a sizable portion of the government deficit

which could not be financed through market subscription was monetised.

However, extending the period of analysis further beyond the automatic

monetisation phase, Ashra et al (2004) found no-long relationship

between fiscal deficit and net RBI credit to the Government and the

latter with broad money supply. Thus, they concluded that there is no

more any rationale for targeting fiscal deficit as a tool for stabilisation.

On the other hand, Khundrakpam and Goyal (2009), including more

recent data and adopting ARDL approach to cointegration analysis,

found that government deficit continues to be a key factor causing

incremental reserve money creation and overall expansion in money

supply, which lead to Inflation.

In this paper, we use a simple model to study the Inflationary

potential of fiscal policy in India by estimating the long-run relationship

and the short-run dynamics between fiscal deficit, seigniorage and

Inflation. The motivation is that fiscal deficit can lead to Inflation either

directly by raising the aggregate demand (demand pull Inflation), or indirectly through money creation, or a combination of both. Against

this background, Section-II presents the challenges associated with

fiscal exit for advanced economies as well as EMEs, and highlights

the issues that are particularly important for India. Section III explains

briefly the analytical framework employed in the paper. In section IV, the

estimation procedures are explained. The data and empirical results are

analysed in section V. Section VI contains the concluding observations.

Section II

The Challenge of Fiscal Exit – What is Important for India?

The unprecedented stimulus that was used across countries to avert

another Great Depression is widely believed to have shown the seeds

of the next crisis. Public debt levels in the advanced economies are

projected to explode to levels never seen during peace-time, leaving

almost no fiscal space for managing other shocks to the economies

in future, besides significantly constraining normalisation of overall

macroeconomic conditions. Some of the projected debt figures look

uncomfortably high – revealing in true sense the trade-offs involved

in policy options. A better today ensured through policy interventions

could enhance risks for the future. In the case of sub-prime crisis, the

impact on the world economy will be permanent and is expected to

persist over several decades through the channel of high public debt.

What then is the dimension of the challenge we are facing today? IMF

projections indicate that in the G-20 advanced economies, Government

debt would reach 118 per cent of GDP in 2014, which will be 40 per

cent higher than the pre-crisis levels. Consolidating the level to about

60 per cent of GDP by 2030 would require raising the average structural

primary balance by 8 per cent of GDP, which is not easy, though not

impossible. But this order of adjustment will involve other costs. One

could first see why the adjustment options may not be easy, and then,

what other costs could result from sustained high levels of public debt.

Why Debt Normalisation could be Difficult?

Many of the advanced economies were preparing their fiscal

conditions to face the challenges associated with demography when the crisis unfolded. The pressure from demography on the fiscal conditions

in terms of social security needs and aging population will increase

over time, whereas the crisis will leave behind additional pressure

arising from the impact of lower potential output and patchy recovery

on revenues and from high unemployment and jobless recovery on

expenditure. Collapse in asset prices also seems to have affected the

funded part of the social security systems. The plausible options for debt

normalization include higher taxes, higher economic growth and the

associated revenue buoyancy, lower expenditure or use of Inflation tax.

Many of the advanced economies already have higher tax/GDP ratios,

and future increases in tax rates may also affect growth. Moreover,

in a globalised world, higher taxes could shift economic activities to

other parts of the world. Lower expenditure, given the constraint of

aging population and high unemployment, and higher debt servicing

associated with the higher debt, could be Difficult. Higher economic

growth, thus, could be the best possible option. Search for new sources

of growth would be a key policy challenge, which has to be also seen in

relation to the rising prominence of EMEs in the global economy and the

competition they would provide in the search for higher productivity.

The Costs of Sustained High Levels of Public Debt

A critical part of the policy challenge associated with high public

debt is to recognize upfront the costs for the economy, without being too

alarmist. Some of the costs seem obvious, even though because of the

non-linearity in the relationships between key evolving macroeconomic

variables, it may not be easy to quantify them. Some of these obvious

costs could be:

(a) Lack of fiscal space to deal with future shocks, including future

downturns in business cycles.

(b) Pressure on interest rates and crowding-out of resources from the

private sector. This effect is not visible as yet because of weak

private demand and expansionary monetary policies. As private

demand recovers and monetary policy cycles turn around, potential

risks will materialize. Three specific channels could exert pressure

on the interest rate: (i) larger fiscal imbalances would imply lower domestic savings, (ii) increase in risk premia, as market would

differentiate between debt levels and expect a premium in relation

to the perceived risk, which is already evident after the experience

of Dubai World and Greece, and (iii) higher Inflation expectations

that would invariably result from high levels of debt, which will be

reflected in the nominal interest rates.

(c) Pressure on central banks to dilute their commitment to and focus

on price stability. In this context, one may see the Inflation tolerance

levels of central banks rising. The IMF’s argument that raising the

Inflation target in advanced economies from 2 per cent to 4 per cent

may not add significant distortions to the economies should also be

carefully examined by central banks. One must recognise why some

feel that return to pre-crisis levels of central bank independence

with focus on price stability would be critical to improve the future

macroeconomic conditions, given the large debt overhang. Price

stability will be critical to ensure high growth, which in turn can

effectively contribute to debt consolidation without imposing costs

of adjustments through other options. The extent of dilution of

central bank independence may also increase if financial stability is

made an explicit mandate of central banks.

How then to Approach Fiscal Exit?

In planning the approach to fiscal exit, the scope for any

complacency based on some misplaced arguments must be avoided.

One such argument could be “no threshold level of debt could be risky”,

given the experience of Japan, which has been operating with very high

levels of debt for quite some time. One cannot ignore the fact that in

Japan private demand has remained depressed for more than a decade,

and much of the debt of the government is held internally as part of

domestic savings. The second flawed argument could be that Dubai and

Greece type shocks cannot cause any systemic global concern since

these shocks are too insignificant for the global economy. The most

dangerous argument, though, could be to support “Inflation tax” as a

means to reduce the real debt burden, on the ground that the alternative

option of higher taxes could be equally distortionary. IMF estimates indicate that higher Inflation in advanced economies at about 6 per cent

maintained over five years could reduce the real debt burden by about

25 per cent (IMF, 2009).

The fiscal exit plans, thus, must involve clarity and commitment.

The broad contours of such strategies may have to emphasise: (a)

medium-term fiscal framework, (b) credible commitment, (c) adoption

of fiscal rules – with scope for deviations to deal with future shocks,

including cyclical slowdowns, and (d) clarity in communication.

Why Fiscal Exit in EMEs Could be Different?

EMEs entered the global crisis with much better fiscal space,

as fiscal discipline was seen generally as a critical aspect of sound

macroeconomic environment to support higher growth. Since the

financial sector of the EMEs did not require any official bailout, the

magnitude of fiscal support needed during the global crisis was also not

as high as in the advanced economies. More importantly, with stronger

recovery ahead of the advanced economies, EMEs can implement fiscal

exit faster without creating concerns for growth. Stronger recovery

in growth will also improve revenue buoyancy. EMEs have to be

particularly careful about fiscal exit, unlike in advanced economies,

since fiscal indiscipline has conventionally created other problems such

as high current account deficit, pressures on Inflation, crowding-out

concerns and even capital outflows. The fiscal exit challenges in EMEs,

thus, will be different from those in the advanced economies.

Fiscal Exit in India

India was on a sustained path of fiscal consolidation prior to the

global crisis, conditioned by the discipline embodied in the Fiscal

Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, 2003. The

FRBM rules required phased reduction in fiscal deficit to 3 per cent of

GDP by end March-2009, with commitment to also eliminate revenue

deficit by that time. The progress on fiscal consolidation turned out to be

faster than initially expected, as high growth during the five year period

2003-08 ensured better revenue buoyancy. Fiscal deficit as percentage

of GDP fell from 4.5 per cent in 2003-04 to 2.6 per cent in 2007-08, leading to attainment of the target one year before what was initially

set under the FRBM rules in 2004. Revenue deficit also declined from

3.6 per cent of GDP to 1.1 per cent of GDP during the corresponding

period. The FRBM, thus, had created considerable fiscal space, led by

revenue buoyancy, when the impact of the global recession on domestic

activities warranted introduction of anti-crisis fiscal response. Some

have viewed the fiscal consolidation as a favourable macroeconomic

condition that contributed to India’s shift to the higher growth trajectory,

even though it is a fact that fiscal consolidation resulted primarily

because of high growth.

When the global crisis started to spread, despite perceptions of

decoupling and a sound financial system at home, there was a clear

risk of slowdown in Indian growth, which had to be arrested through

the appropriate policy response. Because of the heightened uncertainty,

and the “black swan” nature of the series of adverse developments

that unfolded after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the Indian

policy response had to be swift and significant, with a heavy accent

on adequate precaution. Two major fiscal decisions that were taken

earlier, i.e., the farm debt waiver scheme and the Sixth Pay Commission

award, worked like expansionary stimulus, where the decision lag was

almost zero, since the decisions had been taken and partly implemented

even before the crisis-led need for fiscal stimulus was recognised. The

subsequent crisis related fiscal stimulus was delivered in the form of tax

cuts as well as higher expenditure, dominated by revenue expenditure,

as the deceleration in private consumption expenditure turned out to

be significant, which needed to be partly offset by higher government

expenditure. Reflecting the expansionary fiscal stance – involving

a deliberate deviation from the fiscal consolidation path – the fiscal

deficit of the Central Government rose from 2.6 per cent of GDP in

2007-08 to 5.9 percent in 2008-09 and further to 6.7 per cent in 2009-10.

Even the State Governments, which were progressing well on fiscal

consolidation – driven partly by the incentives from the Twelfth Finance

Commission – experienced a setback to the process, resulting primarily

from pressures on revenues and central transfers associated with the

economic slowdown as well as the compelling demand to match the pay revision already announced for Central Government employees.

Gross fiscal deficit of the states, which had improved to 1.5 per cent of

GDP by 2007-08, expanded to 3.2 per cent of GDP in 2009-10.

The role of the expansionary fiscal stance adopted by both the

Central and the State Governments has to be seen in the context of

the fact that private consumption demand, which accounts for close

to 60 per cent of aggregate demand, exhibited sharp deceleration in

growth, from 9.8 per cent in 2007-08 to 6.8 per cent and 4.1 per cent

in the subsequent two years. Government consumption expenditure,

which accounts for just about 10 per cent of aggregate demand, had to

be stepped up significantly to partially offset the impact of the sharp

deceleration in the growth of private consumption demand. Reflecting

the fiscal stimulus, growth in government consumption expenditure was

as high as 16.7 per cent in 2008-09, as a result of which the contribution

of government expenditure to the overall growth in aggregate demand

rose almost three fold – from 10.4 per cent in 2007-08 to 33.6 per cent

in 2008-09. The fiscal stance, thus, had a clear role in arresting sharper

slowdown in economic growth.

Given the possibility of a weak fiscal position operating as a

drag on economic growth in the medium-run – through crowding-out

pressures, besides the scope for causing higher Inflation – the need for

faster return to fiscal consolidation path was recognised quite early in

India, which was articulated and emphasised by the Reserve Bank in

its policy statements, as signs of stronger recovery in growth started

to emerge. By the time the Budget for 2010-11 was announced in

February 2010, better evidence on broad-based momentum in recovery

created the space for gradual roll back of some of the fiscal measures

that were taken in response to the crisis. At the macro level, while gross

fiscal deficit has been budgeted lower at 5.5 per cent of GDP, net market

borrowing programme has also been scaled down by more than 10 per

cent. In terms of specific measures, some of the stimulus-led tax cuts

have been rolled back, greater non-tax revenue from disinvestments and

auction of 3-G/BWA spectrum has been realised and growth in non-plan

expenditure has been significantly curtailed to 4.1 per cent in 2010-11

from 26.0 per cent in the previous year, much of which will result from rationalisation of subsidies. More importantly, indicating the resolve to

return to the fiscal consolidation process, a Medium Term Fiscal Policy

Statement (MTFPS) has been issued along with plans for tax reforms,

both direct and indirect. As per the MTFPS, there will be annual rolling

targets for revenue deficit and gross fiscal deficit so as to reach 2.7

per cent and 4.1 per cent of GDP, respectively, by 2012-13. Goods and

Services Tax (GST) and Direct Tax Code (DTC), to be implemented

in 2011-12, will be critical components of the fiscal consolidation,

which could help in improving the tax to GDP ratio from 10.8 per cent

in 2010-11 to 11.8 per cent in 2012-13. Reflecting the planned fiscal

consolidation, total debt liabilities of the Central Government could

also be expected to moderate from 51.5 per cent of GDP in 2009-10 to

48.2 per cent of GDP in 2012-13. The Indian approach to fiscal exit – in

terms of both adoption of specific fiscal consolidation measures in sync

with the recovery and announcement of medium-term targets for phased

consolidation – reflects the recognition in the sphere of policy-making

of the importance of a disciplined fiscal environment for sustainable

high growth.

The quality of fiscal adjustment, however, must receive greater

attention, given the medium-term double digit growth objective. Like

the previous phase of fiscal consolidation during 2004-08, stronger

recovery in growth will improve revenue buoyancy. Moreover, given

the fact that a large part of the government borrowing (excluding the part

invested by FIIs) is financed domestically, the sovereign risk concerns

would also remain contained. These favourable aspects, however,

should not dilute the focus on consolidation from the expenditure side.

Even if gross fiscal deficit for 2010-11 has been budgeted to decline to

5.5 per cent of GDP from 6.7 per cent in the previous year, that may not

signal any major move in the direction of structural consolidation, if

one removes the one-off components from the revenue and expenditure

sides. Adjusted for disinvestment and 3-G/BWA auction proceeds on

the revenue side, and farm debt waiver and Sixth Pay Commission

arrears on the expenditure side, the reduction in gross fiscal deficit as

per cent of GDP would be much less, i.e. by 0.3 percent as against 1.2

percent envisaged in the Budget. The magnitude and quality of fiscal adjustment could have a significant conditioning influence on India’s

medium-term growth prospects.

In the absence of faster and better quality fiscal adjustment, at least

four major risks to macroeconomic conditions could be envisaged: (a)

the decline in domestic savings, led by the fall in public sector savings,

which will lower the potential output path, (b) higher overall interest

rates, when the revival in demand for credit from the private sector starts

competing with the borrowing programme of the government, (c) limit

the capacity to manage the exchange rate and the domestic liquidity

impact of possible surges in capital flows, since the use of sterilisation

options like the MSS could exert further pressures on the interest rates,

and thereby lead to even higher inflows, and (d) may even force reversal

of reforms, such as use of higher SLR requirements for banks or even

introduction of SLR for non-banking entities in the financial system

to create a captive market for the government borrowing programme.

These possible potential implications signify why fiscal discipline is

so critical in a market based economy. Often, in the search for easy

solutions, direct or indirect monetisation could be preferred, which in

turn could give rise to higher Inflation. This paper primarily highlights

the Inflation risks to India from the fiscal imbalance, and argues that

fiscal space is as critical for managing Inflation as for stabilising the

output path.

Section III

The Analytical Framework

Inflation, according to monetarists, is always and everywhere a

monetary phenomenon. Following the seminal contribution by Sargent

and Wallace (1981), however, it is viewed that fiscally dominant

governments running persistent deficits would sooner or later finance

those deficits through creation of money, which will have Inflationary

consequences. Fischer and Easterly (1990), thus, argue that rapid

monetary growth may often be driven by underlying fiscal imbalances,

implying that rapid Inflation is almost always a fiscal phenomenon.

Historical evidences have shown that governments often resorted

to seigniorage (or Inflation tax) during times of fiscal stress, which had Inflationary consequences. Thus, contemporary macroeconomic

literature, while trying to explain Inflationary phenomenon has also

focussed on the fiscal behaviour, particularly in the developing country

context. This is because fiscally dominant regimes are often seen as

a developing country phenomenon, due to less efficient tax systems

and political instability, which lead to short-term crisis management at

the cost of medium to long-term sustainability. As noted by Cochrane

(2009), “...Fiscal stimulus can be great politics, at least in the shortrun.”

Furthermore, more limited access to external borrowing tends

to lower the relative cost of seignorage in these countries, increasing

their dependence on the Inflation tax while delaying macroeconomic

stabilisation (Alesina and Drazen, (1991) and Calvo and Vegh (1999)).

The relationship between government deficit and Inflation,

however, is more often analysed from a long-term perspective. This

is because borrowing allows governments to allocate seignorage

inter-temporally, implying that fiscal deficits and resort to Inflation

tax need not necessarily be contemporaneously correlated. The shortrun

dynamics between Inflation and deficit is also complicated by the

possible feedback effect of Inflation on the fiscal balance (Catao and

Terrones, 2001). In the short-run, the government might also switch

to alternative sources of financing in relation to seigniorage so that the

correlation between Inflation, deficit and seigniorage is weakened.

A popular method for analysing the Inflationary potential of

fiscal deficit in India is through its direct impact on reserve money,

which via the money multiplier leads to increase in money supply,

that in turn leads to Inflation (for example, Khundrakpam and Goyal,

2009). In this paper, we analyse the Inflationary potential of fiscal

deficit by hypothesising that either: (i) there can be a direct impact on

Inflation through increase in aggregate demand; or (ii) through money

creation or seigniorage; or (iii) a combination of both. The causality is

described in the following flow chart. In essence, though, one has to

recognise that the increase in demand financed by fiscal deficit would

automatically lead to higher money supply through higher demand for

money. In a Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) framework, increase

in money demand associated with higher government demand has to be accommodated, in order to keep the short-term interest rates in the

system, in particular the overnight call rate, within the LAF (repo –

reverse repo) corridor of interest rates. In a LAF based operating

procedure of monetary policy, thus, money supply is demand driven, and

hence endogenous. To the extent that fiscal deficit leads to expansion in

money supply, associated Inflation risk must be seen as a fiscal, rather

than a monetary phenomenon.

|

In this paper, fiscal deficit (D) is defined as total expenditure of

the central government less the revenue receipts (including grants)

less other non-debt capital receipts. In the literature, primary deficit,

which is fiscal deficit less interest payments, is also often considered

in analysing the Inflationary impact of government deficit in order to

remove any possible endogeneity bias resulting from the reverse impact

of Inflation on nominal interest rate.

Seigniorage, which is often referred to as the Inflation tax, could

be defined for simple empirical analysis as the change in reserve money

scaled by the price level. The price level is measured by the wholesale

price index. Thus, seigniorage ‘S’ is defined as,

S = {RM – RM(-1)}/P

Where, RM is the reserve money or base money and P is the index of

price level.

So, we essentially empirically test the following:

i) P = f(D)

ii) P = f(S)

iii) S = f(D)

iv) P = f(D,S)

It is important to note here that ΔRM could be driven by increase

in net foreign assets (NFA) of the RBI as well as net RBI credit to the

government. Under fiscal dominance, much of the increase in RM could

be because of increase in net RBI credit to the government. Under an

exchange rate policy that aims at avoiding excessive volatility, surges in

capital flows and the associated increase in NFA of the RBI could drive

the growth in RM from the sources side. As a result, Inflation may still

exhibit a stronger relationship with money growth, but the underlying

driving factors behind money growth could be the fiscal stance and the

exchange rate policy.

Section IV

The Empirical Framework

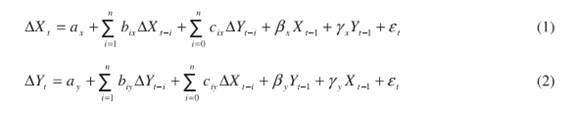

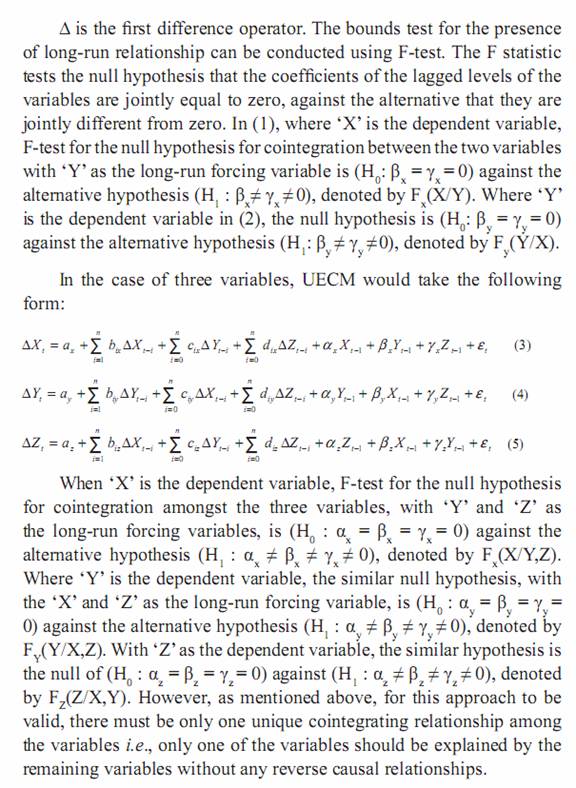

We employ bounds test or ARDL approach to cointegration analysis

developed by Pesaran, Shin and Smith (2001) to examine the stated

empirical hypotheses above. The advantages of this approach are that,

first, it can be applied to variables integrated of different order. Second,

unlike residual based cointegration analysis, the unrestricted error

correction model (UECM) employed in bounds test does not push the

short-run dynamics into the residual terms. Third, the bounds test can

be applied to small sample size. Fourth, it identifies the exact variable

to be normalised in the long-run relationship. A limitation of bounds

test, however, is that it is not appropriate in situations where there may

be more than one long-run relationship among the variables. In other

words, the test is appropriate only when one variable is explained by the

remaining variables and not the vice versa.

This test involves investigating the existence of a long-run

relationship among the variables using an unrestricted error-correction

model (UECM). In the case of two variables, the UECM would take the

following form:

|

|

The F-test has a non-standard distribution which depends upon:

(i) whether variables included in the ARDL model are I(1) or I(0); (ii)

whether the ARDL model contains an intercept and/or a trend. There are critical bound values of both the statistics set by the properties of

the regressors into purely I(1) or I(0), which are provided in Pesaran,

Shin and Smith (2001) for large sample size. The critical bound values

for F-test in the case of small sample size are estimated in Narayan

(2005). If the absolute value of the estimated F-statistics: (i) lie in

between the critical bounds set by I(1) and I(0), cointegration between

the variables is inconclusive; (ii) in absolute value lower than set by

I(0), cointegration is rejected; and iii) in absolute value higher than set

by I(1), cointegration is accepted.

For the equation which shows cointegrating relationship, the

conditional long-run relationship is estimated by the reduced form

solution of the following ARDL equations. If ‘X’ is the explained

variable the specification takes the form:

The ECT term in (7) is the error obtained from the long-run

relationship in (6).

The error correction model described by (7) can be used to

generate dynamic forecast of the explained variable based on the past

and current values of the independent variables. The accurateness of

the dynamic forecast could indicate the robustness of the estimated

model.

Section V

Data and Empirical Results

We cover the time period 1953 to 2009. The relevant data on

price (wholesale price index) and reserve money are obtained from

Monetary Statistics and Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy,

RBI. Data on Central Government fiscal deficit from 1971 onwards

are obtained from Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, while that for the earlier period was taken from Pattnaik et al (1999). Two

time periods were considered, mainly with the purpose of generating

dynamic forecast and checking the robustness of the model. The first

time period is from 1953 to 2005, which excludes the post-FRBM

period when direct lending to Government by the RBI was discontinued

under the FRBM Act.

Unit Root Tests

To gauge the appropriateness of the ARDL cointegration analysis,

two unit root tests viz., ADF test and PP test were conducted for the two

sample periods. It was found that there are contradictions in the unit

root properties based on the alternative tests for the price variable and

between the two sample periods on government deficit. On the other

hand, seigniorage is indicated to be a stationary series by both the tests

and for both the sample periods. The overall picture that emerged was

that the three variables considered are not necessarily integrated of the

same order (Table 1). In view of this, we used bounds tests, which are

valid when variables are integrated of different order (Pesharan, Shin

and Smith, 2001).

Bounds Tests

Bounds test results are extremely sensitive to the presence of

serial correlation and the lag length selected. In order to remove the possible presence of serial correlations, dummies were included to

remove outliers. With price as the explained variable, the outliers

were found in 1974 and 1975 coinciding with the after affects of oil

price shock of 1973. Fiscal deficit outliers were found in 1955 and

2009, coinciding with the initiation of the Second Five Year Plan and

the recent fiscal stimulus measures following economic slowdown

due to the global financial crisis, respectively. The outliers with

respect to seigniorage were found during the years of 1975, 1976 and

1977, which were the years of extreme volatility in prices and money

growth. Given the use of annual data, the maximum lag length was

set at 2 and the appropriate lag length was selected based on SBC

criterion.1 This was considered appropriate since the sample size is

small (in the statistical sense) and therefore including too many lags

may lead to loss of explanatory power.

Table 1 : Unit Root Tests |

Variable (X) |

ADF |

PP |

X |

ΔX |

X |

ΔX |

1953 to 2005 |

|

|

|

|

LogP |

-3.21(t) |

-5.20* |

-4.94(t)* |

-6.22* |

LogS |

-5.59(t)* |

-8.93* |

5.60(t)* |

-24.4* |

LogD |

-3.10(t) |

-6.96* |

-3.16(t) |

-6.98* |

1953 to 2009 |

|

|

|

|

LogP |

-2.93(t) |

-6.43* |

-4.36(t)* |

-6.44* |

LogS |

-5.50(t)* |

-9.09* |

5.53(t)* |

-24.6* |

LogD |

-3.58(t)** |

-6.82* |

-3.63(t)** |

-6.69* |

Note: * and ** denote statistical significance at 1% an d 5% levels, respectively, ‘t’

in parentheses denote that the tests included a trend along with the constant. |

The bounds test results among the variables during both the sample

periods reported in table-2 reveal the following:

(i) Between price and seigniorage, the F-statistics are above the

95% critical bound values (9.74 and 7.18 for the two sample

periods) and significant at 99% critical level only when price

is explained by seigniorage. The F-statistics for the reverse

relationships (3.13 and 2.67) are statistically insignificant. In

other words, there exists a long-run cointegrating relationship

between price level in the economy and government resorting to

seignorage to finance its deficits, but with the former only being

caused by the latter;

(ii) Between price and government deficit, the F-statistics for the two

sample periods are 6.17 and 7.96 and statistically significant only

when price is explained by government deficit. In the case of the

reverse relationship, the F-statistics are 3.34 and 2.27 and are lower

than 95% critical bound values and hence not significant. Thus, in

the long-run, government deficit has an impact on price level in the

economy, but the reverse impact is insignificant;

(iii) Seigniorage is also explained by government deficit with

F-statistics of 8.14 and 5.32 for the two sample periods, but the reverse relationships are not statistically significant, given the

corresponding F-statistics of 0.39 and 0.48. The implication is

that government resorts to seigniorage to finance its deficit in the

long-run, but there is no significant reverse impact.

(iv) When all the three variables are combined, only price is explained

by seigniorage and government deficit with F-statistics of 6.42 and

5.83 for the two sample periods. None of the reverse relationships

are statistically significant. The respective F-statistics for the two

sample periods are 2.51 and 1.85 with government deficit as the

explained variable and 0.83 and 0.56 with seigniorage as the

explained variable. In other words, ceteris paribus, price level in

the economy in India, in the long-run, is significantly influenced

either directly by deficit itself or through the creation of money

via deficit financing, or a combination of both. In other words,

Inflation is indicated to be explained by government deficit

either directly or through seigniorage indirectly or through a

combination of both the factors. Further, the results that there

is only one cointegrating relationship between the variables in

all the alternative combinations clearly indicates that the ARDL

approach to cointegration can be used for estimation of the longrun

relationships and the short-run dynamics.2

Long-run Coefficients

In estimating the long-run Coefficients a trend component was

included in the price equations as a proxy to capture the impact

of other macroeconomic variables on price. The results presented

in table-3 reveal some interesting features. While the signs of the

Coefficients are as expected a priori in all the equations, some of them

are not statistically significant. specifically, the Coefficients of fiscal

deficit in the price equations are insignificant in the shorter sample

period (column 2 and 4), but turn significant in the full sample period

(column 6 and 8). Conversely, the Coefficients of seiniorage which

are significant in the shorter sample period (column 1 and 4) turn

insignificant in the full sample period, particularly with the inclusion

of fiscal deficit as the other explanatory variable (column 5 and 8).

Table 2 : Bounds test for Cointegration |

Functional Relationship |

1952-2005 |

1952-2009 |

F-Statistics |

95% critical Values |

Dummy variables |

F-Statistics |

95% critical Values |

Dummy variables |

Bivariates |

Fp(P/S) |

9.74* |

4.44 |

1974 & 1975 |

7.18* |

4.393 |

1974 & 1975 |

Fs(S/P) |

3.13 |

4.44 |

|

2.67 |

4.393 |

|

Fp (P/D) |

6.71* |

4.44 |

1974 & 1975 |

7.96* |

4.393 |

1974 & 1975 |

Fd (D/P) |

3.34 |

4.44 |

1955 |

2.27 |

4.393 |

1955 & 2009 |

Fs(S/D) |

8.14* |

4.44 |

1975, 1976 & 1977 |

5.32** |

4.393 |

1975, 1976 & 1977 |

Fd(D/S) |

0.39 |

4.44 |

|

0.48 |

4.393 |

2009 |

Trivariates |

Fp(P/S,D) |

6.42* |

4.178 |

1974 & 1975 |

5.83* |

4.10 |

1974 & 1975 |

Fd(D/S,P) |

2.51 |

4.178 |

|

1.85 |

4.10 |

2009 |

Fs(S/D,P) |

0.83 |

4.178 |

1959 & 1997 |

0.56 |

4.10 |

1959 & 1997 |

Note: * and ** denote statistical significance at 99% and 95% critical levels,

respectively. The critical bound values for F-statistics are from Narayan (2005). |

This could indicate that till the ban on direct government borrowing

from the RBI, the Inflationary impact of fiscal deficit worked primarily

through money creation and overshadowed the direct impact, if any.

However, in recent years, with limited scope for direct monetisation,

the Inflationary impact of fiscal deficit is generated more directly

perhaps via the channel of increase in aggregate demand.

Individually, one percent increases in seigniorage leads to about

one-third of a percent increase in the price level in both sample periods,

though the level of statistical significance declines (column 1 and 5).

With regard to fiscal deficit, one per cent increase in it leads to about one-fifth to one-quarter of a per cent increase in the price level, which

though is statistically significant only for the full sample period (column

2 and 6).

Table 3 : Long-run Coefficients |

|

1954-2005 |

1954-2009 |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

LogP |

LogP |

LogS |

LogP |

LogP |

LogP |

LogS |

LogP |

Constant |

4.50 |

3.30 |

-3.01 |

3.75 |

4.53 |

3.0 |

-3.18 |

3.23 |

| |

(21.6)* |

(5.4)* |

(-12.8)* |

(6.4)* |

(17.6)* |

(5.1)* |

(-10.7)* |

(5.3)* |

LogS |

0.31 |

|

|

0.23 |

0.32 |

|

|

0.2 |

| |

(2.1)** |

|

|

(1.8)*** |

(1.7)*** |

|

|

(1.3) |

LogD |

|

0.19 |

0.483 |

0.13 |

|

0.25 |

0.51 |

0.24 |

| |

|

(1.5) |

(19.3)* |

(1.2) |

|

(2.1)** |

(16.6)* |

(2.1)** |

Trend |

0.06 |

0.05 |

|

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

|

|

| |

(6.1)* |

(3.3)* |

|

(3.4)* |

(4.0)* |

(2.9)* |

|

|

DumP |

0.71 |

0.79 |

|

0.67 |

|

0.90 |

|

0.93 |

| |

(0.71)** |

(2.6)* |

|

(2.5)** |

|

(2.64)** |

|

(2.2)* |

DumS1 |

|

|

-.97 |

|

|

|

-1.25 |

|

| |

|

|

(-3.2)* |

|

|

|

(-2.85)* |

|

Note: *, ** and *** denote statistical significance at 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Dummy as indicated in the bounds test. |

The above estimated elasticities, however, ignore the interaction

between seigniorage and government deficit. It is seen from column

(3) and (7) that to finance one percent of fiscal deficit in the long-run,

seigniorage increased by about 0.48 to 0.51 percent, with other things

remaining the same.

Combining both government deficit and seigniorage,one percent

increase in seigniorage was found to cause Inflation by about onefi

fth of a percent in both the sample periods, but is not statistically

significant for the full period. With regard to one per cent increase

in government deficit, the impact which was small (0.13) and not

statistically significant in the shorter sample period, increased in the

full sample period to a statistically significant level of about a quarter

of a percent increase in the price level. It may, thus, be interpreted

that, in the more recent years, the direct long-run Inflationary impact of seigniroage has declined while that of government deficit through

aggregate demand channel has increased. However, the long-run

impact of government deficit on seigniorage revenue appears to have

not declined.

Short-run Dynamics

The short-run dynamics presented in Table-4 reveal that all the

equations are stable i.e., they converge to the long-run equilibrium

as indicated by the negative sign of the error correction term. The

explanatory powers are reasonable and the problem of serial correlation

is within the tolerable level in general. There, however, seems to be

some decline in the explanatory power after the inclusion of more

recent periods.

The Inflationary impact of seigniorage in the short-run is neglisible,

irrespective of whether it is considered alone or taken together with

government deficit in the model in both the sample periods (columns

1, 4, 5 and 8). The speed of convergence following a shock is also very

slow, about 16 to 17 percent in a single year when considered alone and

about 16 to 20 percent when deficit is also included.

Government deficit, on the other hand, has a positive impact on

Inflation even in the short-run for the full sample period indicating that

the direct Inflationary impact of government deficit could have become

more prominent in the more recent years.

With regard to the impact of government deficit on seigniorage,

there is a strong positive impact even in the short-run. The impact was

larger in the shorter sample period and the speed of convergence was

also higher with about 92 per cent of the divergence from the long-run

equilibrium following a shock being corrected in a single time period.

Both the short-run impact and speed of convergence decline in the full

sample period, indicating that government may have switched over

to alternative source of financing its deficit in the short-run given the

restriction on direct borrowing from the RBI since the beginning of

fiscal 2006.

Table 4 : Short-run Dynamics |

|

1954-2005 |

1954-2009 |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

ΔLogP |

ΔLogP |

ΔLogS |

ΔLogP |

ΔLogP |

ΔLogP |

ΔLogS |

ΔLogP |

Constant |

0.79 |

0.62 |

-2.78 |

0.75 |

0.73 |

0.52 |

-2.38 |

0.51 |

| |

(3.1)* |

(2.7)* |

(-5.3)* |

(3.1)* |

(2.8)* |

(2.5)** |

(-4.26)* |

(2.2)** |

ΔLogP-1 |

|

|

|

|

0.33 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

(2.4)** |

|

|

|

ΔLogS |

0.00 |

|

0.29 |

-0.00 |

-0.01 |

|

0.24 |

-0.00 |

| |

(0.01) |

|

(2.6)** |

(-0.2) |

(0.61) |

|

(1.96)*** |

(-0.6) |

ΔLogD |

|

0.04 |

0.45 |

0.03 |

|

0.04 |

0.38 |

0.04 |

| |

|

(1.5) |

(5.9)* |

(1.1) |

|

(2.2)** |

(4.8)* |

(1.9)*** |

Trend |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

0.00 |

| |

(2.0)** |

(2.2)** |

|

(1.9)*** |

(1.6) |

(1.9)*** |

|

(1.1) |

DumP |

0.12 |

0.15 |

|

0.13 |

|

0.16 |

|

0.15 |

| |

(4.6)* |

(4.5)* |

|

(4.7)* |

|

(5.0)* |

|

(5.2)* |

DumS1 |

|

|

-0.90 |

|

|

|

-0.94 |

|

| |

|

|

(-4.0)* |

|

|

|

(-3.8)* |

|

ECM(-1) |

-0.17 |

-0.19 |

-0.92 |

-0.20 |

-0.16 |

-0.127 |

-0.75 |

-0.16 |

| |

(-2.76)* |

(-3.4)* |

(-4.93)* |

(-2.97)** |

(-2.43)* |

(-3.27)* |

(-5.17)* |

(-2.42)** |

R-bar Square |

0.52 |

0.40 |

0.57 |

0.52 |

0.27 |

0.40 |

0.46 |

0.47 |

DW-Statistics |

1.75 |

1.65 |

1.88 |

1.73 |

2.02 |

1.64 |

1.82 |

1.64 |

Note : *, ** and *** denote statistical significance at 1%, 5% and 10% levels,

respectively. Dummy as indicated in the bounds test. |

As mentioned above, dynamic forecasts of Inflation for the period

2006 to 2009 were generated from the models estimated for the period

1953 to 2005 and then compared with the actual change. The forecast

results are presented in Table-5. It could be seen that the direction

of actual Inflation are correctly predicted irrespective of whether

seigniorage and government deficit are combined or considered

individually. However, the Inflation rates in each of the four years

are over-predicted The root mean square errors of predictions for the

forecast period are also marginally higher than for the estimation period,

except when government deficit is considered as the only explanatory

variable. However, root mean square errors are about or less than 5.0

per cent, indicating that the forecast performance may be reasonable.

Table 5 : Dynamic Forecasts for 2006 to 2009 |

(in per cent) |

|

Change in P due to change in S and D |

Change in P due to change in S |

Change in P due to change in D |

|

Actual |

Predicted |

Actual |

Predicted |

Actual |

Predicted |

2006 |

4.28 |

8.8 |

4.28 |

9.67 |

4.28 |

8.1 |

2007 |

5.28 |

8.7 |

5.28 |

9.97 |

5.28 |

7.5 |

2008 |

4.65 |

9.4 |

4.65 |

11.2 |

4.65 |

6.7 |

2009 |

8.01 |

13.0 |

8.01 |

12.6 |

8.01 |

9.7 |

Root mean square |

Estimation Period |

Forecast period |

Estimation Period |

Forecast period |

Estimation Period |

Forecast period |

3.3 |

4.4 |

3.3 |

5.3 |

3.9 |

2.6 |

Section VI

Concluding Observations

The fiscal response in India to the severe contagion from the global

crisis was conditioned by the need to minimize the adverse impact on

the domestic economy. In the process, however, India’s fiscal deficit

expanded again to the pre-FRBM level. Given India’s past experience,

in terms of fiscal consolidation resulting only over a number of years,

downward inflexibility of the post-crisis high fiscal deficit level could

emerge as a potential source of risk to India’s future path of Inflation.

During 2008-10, when the fiscal stimulus led to increase in the

fiscal deficit level, India’s Inflation environment remained highly

volatile, reaching a peak in 2008-09 under the influence of the global

oil and commodity prices shock, and coming under pressure again in

2009-10 from another supply shock, but from within the country, in the

form of significant increase in food prices resulting from the deficient

monsoon. In this Inflation process over these two years, however,

fiscal deficit did not have much of a contributing role, since: (a) the

overall private demand remained depressed, and fiscal expansion only

aimed at partially offsetting the impact of deceleration in the growth

of private consumption and investment demand on economic growth,

(b) large borrowing programme of the Government did not lead to

high money growth, since the growth in demand for credit from the

private sector exhibited significant deceleration, and (c) certain fiscal

measures like cuts in indirect tax rates in fact helped in lowering the

prices of specific goods and services to some extent. Thus, the usual two channels through which fiscal deficit could cause Inflation - i.e. by

exerting pressure on aggregate demand in relation to potential output

and by leading to excessive expansion in money growth - were almost

absent. As demand for credit from the private sector has revived, and if

capital inflows remain strong on a sustained basis, the usual downward

inflexibility in fiscal deficit and its implications for the future Inflation

path will start to emerge over time.

In this context, this paper examined the empirical relationship

between fiscal deficit and Inflation over the pre-FRBM period 1953-

2005 as well as the full sample period of 1953-2009. The direct impact of

fiscal deficit through primary expansion in reserve money was studied by

using a concept of ‘seigniorage’, proxied by the annual change in reserve

money deflated by WPI Inflation.Net RBI credit to the government and

RBI’s increase in net foreign assets are the two key determinants of

growth in reserve money on the sources side, and hence, only part of

the increase in reserve money could be ascribed to the fiscal stance at

any point of time. The overall impact of the fiscal deficit on Inflation, in

turn, could operate through both increases in aggregate demand as well

as associated growth in broad money. In both direct as well as overall

analysis, thus, the role of money in Inflation becomes obvious, but that

process could be significantly conditioned by the fiscal stance.

Bounds test results presented in the study suggest that: (a) there

is a cointgrating relationship between the price level and seigniorage

financing of deficit; (b) fiscal deficit and price level also exhibit a similar

relationship, and in both cases the price level appears to be determined

by seigniorage or fiscal deficit, not the other way round; (c) the role

of seigniorage in the Inflation process may be declining over time,

particularly in recent years, even though the impact of fiscal deficit on

Inflation through aggregate demand channel might have increased; (d)

one percentage point increase in the level of fiscal deficit is estimated

to cause as much as a quarter of a percentage point increase in WPI;

and (e) as per the analysis of short term dynamics through which fiscal

deficit may get transmitted to Inflation, fiscal deficit appears to have

a positive impact on Inflation even in the short-run, though modest.

These empirical findings suggest that while the fiscal stance in India was appropriate in the context of the economic slowdown that followed

in response to the global crisis, it may have medium-term potential

ramifications for the Inflationary situation. This possibility, in turn,

highlights the significance of return to fiscal consolidation path at the

earliest, with an emphasis on the quality of fiscal adjustment, driven

by rationalisation of expenditure rather than revenue buoyancy from

stronger growth. Build up of adequate fiscal space is important not only

for ensuring stability to the high growth objective but also for enhancing

the ability to deal with such Inflationary pressures that may originate

from temporary supply shocks, as experienced in recent few years.

___________________________________________________________

* Shri Jeevan Kumar Khundrakapam and Shri Sitikantha Pattanaik are Directors in

Monetary Policy Department and Department of Economic and Policy Research,

respectively. The earlier version of the paper was presented in the 12th Conference

on Money & Finance organised by IGIDR, Mumbai during March 11-12, 2010.

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referee for useful comments. The paper

reflects the personal views of the authors.

Notes :

1 It was, however, found that increasing the maximum lag length to 3 or 4

hardly affected the results.

2 As mentioned above, for Bounds test to be valid, the long-run relationship

between the variables should be only in one direction.

References :

Aghevli, B.B., and Khan, M. (1978), “Government deficits and the Inflationary

Process in Developing Countries,” IMF Staff Papers, 25, 383-416.

Alesina, Alberto and Drazen, Allan (1991), “Why are Stabilisations Delayed?”,

American Economic Review, Vol. 81, 1170-1188.

Ashra, S., Chattopadhyay, S., and Chaudhuri, K. (2004), “deficit, Money and

Price – the Indian Experience”, Journal of policy Modeling, 26, 289-99.

Calvo, Guillermo and Vegh, Carlos (1999), “Inflation Stabilisation and BOP

Crisis in Developing Countries,” in John Taylor and Michael Woodford (Ed).,

Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume C, North Holland.

Catao Luis and Marco Terrones (2001), “Fiscal deficits and Inflation: A New

Look at the Emerging Market Evidence”, IMF Working Paper WP/01/74.

Cecchetti, Stephen G, M. S. Mohanty and Fabrizio Zampolli (2010), “The

Future of Public Debt: Prospects and Implications”, BIS Working Papers No.

300, March.

Fischer Stanely and William Easterly (1990), “The Economics of the

Government Budget Constraint”, World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 5(2),

127-142.

Cochrane, John H. (2009), “Fiscal Stimulus, Fiscal Inflation, or Fiscal

Fallacies?”, University of Chicago Booth School of Business, February 27..

Davig, Troy and Erie M. Leeper (2009), “Monetary-Fiscal Policy Interactions

and Fiscal Stimulus”, NBER Working Paper Series 15133, July.

IMF (2009), “ The State of Public Finances Cross-Country Fiscal Monitor”,

IMF Staff Position Note (SPN/09/25), November.

Jadhav, N. (1994). Monetary Economics for India. Delhi: Macmillan India

Limited.

Khundrakpam J.K. and Rajan Goyal (2009), “Is the Government deficit in

India Still Relevant for Stabilisation?,” RBI Occasional Papers, Vol.29 (3),

Winter 2008.

Narayan, P.K. (2005), “The Saving and Investment Nexus for China: Evidence

from Co-integrating Tests”, Applied Economics, 35, 1979-1990.

Pattnaik, R.K., Pillai, S.M., and Das, S. (1999), “Budget deficit in India: A

Primer on Measurement”, RBI Staff Studies, Reserve Bank of India.

Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y. and Smith, R.J. (2001), “Bound Testing Approaches

to the Analysis of Level Relationships”, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16,

289-326.

Rangarajan, C., and Mohanty M.S. (1998), “Fiscal deficit, External Balance

and Monetary Growth”, Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, 18, 635-

653.

Reserve Bank of India (2006), Handbook of Monetary Statistics of India.

Reserve Bank of India (2009), Handbook of Statistics of the Indian economy,

2008-09.

Sarma , Y.S.R. (1982), “Government deficits, Money Supply and Inflation in

India”, Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers. Mumbai, India.

Sargent, Thomas J. and Neil Wallace (1981), “Some Unpleasant Monetarist

Arithmetic”, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, Vol.

5(3), 1-17.

Vinals, Jose and Paolo Mauro (2010), “A Strategy for Renormalising Fiscal

and Monetary Policies in Advanced Economies”, KDI/IMF Workshop, Seoul

Korea, February 25, 2010.

Woodford, Michael (2001), “Fiscal Requirements for Price Stability”, National

Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper, 8072. |