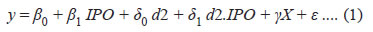

Avdhesh Kumar Shukla and Tara Shankar Shaw* This paper makes an assessment of how the operating performance of Indian firms change after their initial public offerings (IPOs). It finds that there is no deterioration in the operating performance post IPO, if a performance indicator like ‘profit’ is normalised by sales volumes (i.e., return on sales) rather than assets (i.e., return on assets). Unlike a distinct decline in return on assets reported in similar other studies, this paper finds a stable return on sales. The paper highlights the importance of choice of right variables for matching and normalisation purposes. JEL Classification : O16, G32, G39 Keywords : Initial public offers, return on assets, turnover ratio, promoters’ shareholding and agency relationship Introduction In the life of a firm, transition from a privately-owned to a public-owned firm through an initial public offering (IPO) is probably the most important event (Pagano et al., 1998). The existing economic and financial literature has studied a number of issues relating to firms’ performance after an IPO, such as under-pricing of IPOs (Ibbotson, 1975; Ritter, 1984), firms’ underperformance post issuance (Ritter 1991, Loughran and Ritter 1995), and firms’ operating performance after going public (Bruton et al., 2010; Cai and Wei, 1997; Jain and Kini, 1994; Kim et al., 2004; Mikkelson et al., 1997). These studies have concluded that IPO firms’ profitability, measured as a ratio of operating profit to total assets, was lower in the post-issue period than in the pre-issue period. In the Indian context also, Janakiramanan (2008), Kohli (2009), Bhatia and Singh (2013) and Mayur and Mittal (2014) have concluded that return on assets (ROA) of IPO firms decline post-issuance. Most of the studies in the Indian context have covered a period after the 1990s. Since the initiation of economic reforms in the early 1990s, the Indian capital market has witnessed a spate of reforms. The initial phase of reforms comprised mainly of liberalisation and consolidation, while reforms in the 2000s aimed at putting a robust regulatory structure in place and increasing the integrity of both markets and institutions. Important reforms implemented during this period were related to introduction of fit and proper criterion for public issuers, Clause 49 relating to rules of listing, book building norms, and submission of annual and quarterly financial statements, among others. Marisetty and Subrahmanyam (2010) have termed the period after 2000 as the reformed regulated era of the Indian capital market. Consequent upon these reforms and policy changes, the Indian IPO market has increased in complexity and size. It has emerged as one of the most important markets for global investors among emerging market economies. In this backdrop, it is worthwhile to revisit post-issue performance of Indian firms to analyse changes in firms’ behaviour in the reformed regulated era. Various reforms were intended to increase the entry and survival of good firms over firms with poorer credentials. An analysis of post-issue operating performance of firms will indicate whether regulation has resulted in any distinctive shift in their performance. Majority of studies focusing on this area, particularly those relating to advanced economies, have generally concluded that IPO firms underperform post-issue vis-à-vis their pre-issue performance. In this study, we have analysed the operating performance of IPO firms in the long run after controlling for firms’ ownership structure and size using univariate and difference-in-differences regression (DID) method. The findings of our study indicate that IPO firms’ ROA and turnover ratios (TOR) record decline after issue while the ratio of net operating cash flows to total assets (RCFA) declines in the first-year post-issuance but recovers in subsequent years. At the same time, return on sales1 (ROS) does not show any statistically significant decline. We find that faster expansion of asset base of IPO firms immediately after issue largely explains the decline in asset-scaled performance variables such as ROA. The decline is not observed when profit is scaled by sales. Furthermore, when IPO firms are matched on the basis of pre-issue performance, as suggested by Barber and Lyon (1996), decline in ROA is smaller. This study contributes to the existing literature in two important ways: first, the study finds that ROS of Indian IPO firms does not decline after issue and, second, the decline in asset-scaled variables is moderate when firms are matched in terms of ROA. As majority of the literature, following Jain and Kini (1994) has focused on ROA, the finding of a stable ROS is important. To our knowledge, this is the first study analysing the performance of IPO firms floated during the post-reforms regulated era. Furthermore, apart from asset-scaled variables, the study analyses sales-scaled variables, hence controlling for natural bias. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section II covers theoretical underpinnings and literature survey. Section III explains research methodology and data along with data sources; Section IV discusses descriptive statistics. Section V outlines univariate analysis, followed by a narrative on regression results in Section VI. Conclusions are given in Section VII. Section II Theoretical Underpinnings and Literature Survey The focus of this paper is to examine the impact of a firm's decision to go public on its operating performance. There is a large body of literature analysing the post-issue performance vis-à-vis pre-issue performance of a firm (Cai and Wei, 1997; Jain and Kini, 1994; Kao et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2004; Mikkelson et al., 1997; Pagano et al., 1998). Literature indicates that IPO firms’ post-issue performance relative to their pre-issue performance declines mainly due to agency cost (Bruton et al., 2010; Jain and Kini, 1994), entrenchment behaviour (Kim et al., 2004) and window of opportunity behaviour (Cai and Wei, 1997; Loughran and Ritter, 1995). Lyandres et al. (2007) support an investment-based explanation of decline in performance, whereby firms go for aggressive physical investment after the issue. In the investment-based explanation, firms are not able to exploit their new investment efficiently and hence make relatively lower profits. Agency cost arises due to ‘separation of ownership and control’, or ‘principal-agent problem’ in a public firm (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). According to the agency theory, agency cost may manifest in the form of increased consumption of non-pecuniary benefits by firm managers or lower efforts to maximise its value. An IPO leads to a reduction in ownership of existing owner-managers which results in agency problem between owner-managers and new shareholders leading to an increase in agency cost. This predicts a linear relationship between managerial ownership and operating performance of a firm (ibid.). Entrenchment hypothesis, on the other hand, indicates that convergence of interest between a firm and its owner-manager occurs at lower and higher levels of ownership by the firm’s managers (Morck et al., 1988). This suggests that a firm’s performance initially deteriorates as managerial ownership increases, and then tends to improve as their ownership increases further. Besides, we may observe a decline in the post-issue operating performance if firms time their issue. Firms going for an IPO have an incentive to time it when their performance is at its peak so as to get the highest possible return. Firm managers also time the market to bring the issue at the peak of the market. This hypothesis is known as ‘window of opportunity’ hypothesis (Ritter, 1991; Loughran and Ritter 1995). One of the early empirical studies on this topic, Jain and Kini (1994), found that IPO firms exhibit a decline in post-issue operating performance due to an increase in agency cost. They found a positive and linear relationship between promoters’2 share in equity holding of a firm and its performance. Mikkelson et al. (1997) also concluded that the operating performance of IPO firms declines post-issuance. However, unlike Jain and Kini (1994), they did not find any relationship between firms’ operating performance and retained ownership of the owner-manager. They attributed the decline in post-issue performance of IPO firms to their relatively younger age and smaller size, which disables them from sustaining their competitive advantage, as they lack adequate managerial skills and economies of scale. In a relatively underdeveloped market structure of the Thai economy, Kim et al. (2004) tested the entrenchment hypothesis by using a cubic function and concluded that there was a curvy-linear relationship between ownership share of owner-manager and firm performance. Use of cubic function by Kim et al. (2004) allows for “three levels of managerial ownership”. They found that managerial ownership between 0–31 per cent and 71–100 per cent leads to an increase in post-issue performance, while it decreases for firms with managerial ownership between 31 and 71 per cent. Their findings on Thai IPO firms support the entrenchment theory of Shleifer and Vishny (1989) and Morck et al. (1988). Recent literature has focused on the impact of large-block shareholding on post-issue operating performance of IPO firms (Bruton et al., 2010; Jain and Kini, 1995; Krishnan et al., 2011; Rindermann, 2004). Agency relation literature has considered 'block holding' as an important governance mechanism as it contains agency cost in multiple ways. A large block shareholding signifies alignment of managers’ interests with that of the firm’s, leading to reduced adverse selection (Leland and Pyle, 1977). It also reduces coordination cost among dispersed owners. However, in the case of divergence in economic goals, block shareholders may pose conflicting agency problems. Analysing performance of IPO firms of the United Kingdom (UK) and France, Bruton et al. (2010) concluded that venture capital (VC) funds, whose goal is to earn a high return within a short period of time, adversely affect IPO firms’ performance, while long-term angel funds affect their performance favourably (Annex). Corporate governance literature emphasises that unlike advanced economies that are characterised by principal-agent problems, emerging economies manifest principal-principal conflict which is attributed to concentrated ownership and control, poor institutional protection to minority shareholders and weak governance structure (Young et al., 2008). Cai and Wei (1997) argued that financial institutions in Japan, such as banks and insurance companies, are permitted to own sizeable share in a firm’s equity and are allowed to have representation in the board, which reduces the agency problem and managerial entrenchment behaviour in Japanese firms. Pagano, et al. (1998) argued that post-issue decline in investment and profitability of the IPO firm points towards a window of opportunity. In a tad different financial set up in China, where state-controlled firms go for public issue, Wang (2005) found coexistence of agency conflicts, management entrenchment and large shareholders’ expropriation. In another study on newly-privatised firms in China, Fan et al. (2007) found that the post-issue decline in operating performance is more pronounced in firms where the chief executive officer (CEO) is politically connected, and, which have weak corporate governance structure. Barber and Lyon (1996) have criticised event studies relating to IPOs and have argued that in the case of IPO firms, performance variables such as ROA give biased results as asset size of firms changes significantly post-issuance. According to them, literature has generally ignored this fact while selecting control firms. They suggested that instead of size, firms should be matched by the relevant variables. They favoured use of profit scaled by sales. Supporting the hypothesis of Barber and Lyon, Brav and Gompers (1997) and Kothari et al. (2005) found that post-issue decline of performance was concentrated in small firms. Lyandres et al. (2007) matched IPO firms using investment to asset ratio and concluded that IPO firms invest heavily in real assets and exhaust higher net present value opportunity leading to lower return afterwards. Though India has a thriving IPO market, there are not many studies on post-issue performance of IPO firms. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, India witnessed a number of capital market reforms (Goswami, 2001; Marisetty and Subrahmanyam, 2010) putting in place a world-class regulatory and governance regime in the country. Most studies focus on the period immediately after or prior to the reforms, but do not adequately cover the reformed regulated era, i.e., the period after the 2000s. Results of studies on operating performance of IPO firms in India are mixed. Ghosh (2005) did not find any decline in post-issue performance of Indian banks. Kohli (2009), on the other hand, found that post-issue operating performance of IPO firms decline, both with and without industry adjustment. The main goal of this study was to compare the allocative efficiency of resources in a market-based system (stock market) vis-à-vis a bank-based system. Kohli attributed the decline in ROA of IPO firms to the relative inefficiency of the market-based structure in India. He did not attempt to find out the causes of decline in firm performance. Mayur and Mittal (2014), following the methodology of Kim et al. (2004), found the presence of entrenchment behaviour of controlling managers in India. In line with the existing literature, studies in India have mainly focused on asset-scaled variables. Though literature survey indicates a near unanimity on decline of operating return in IPO firms after issue; there is no agreement on causes of such a decline. Section III Data and Methodology Data This study is based on a sample of non-financial private firms in India, which had floated their IPOs during April 1, 2000 to March 31, 2011. The study focuses on their long-term operating performance, for which it uses a minimum of three years post-issue data. Thus, the data upto end of March 2011 allows assessment of performance up to 2014. The data are extracted from Prowess database maintained by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). Our sample consists of 413 IPO firms. There is considerable amount of variability in terms of numbers of issuances during the studied period. Largest numbers of issues were floated in 2000-01 followed by 2007-08 (Table 1). | Table 1: Year-wise Distribution of Issues | | Financial year | No. of issues | | 2001 | 91 | | 2002 | 4 | | 2003 | 3 | | 2004 | 14 | | 2005 | 18 | | 2006 | 53 | | 2007 | 50 | | 2008 | 78 | | 2009 | 20 | | 2010 | 36 | | 2011 | 46 | | Total | 413 | The study employs ROA, RCFA, ROS, asset turnover ratio (TOR) and sales growth as indicators of operating performance. Multiple variable approach was preferred, as a single variable gives only partial information about performance. ROA was calculated as a ratio of profit before depreciation, interest, taxes and amortisation (PBDITA) to total assets. As operating income is based on accrual accounting, it is prone to manipulation (Barber and Lyon, 1996). This can be addressed by use of operating cash flows. Difference between net operating cash flow and PBDITA is that the latter does not take into account changes in working capital and capital expenditure. Net operating cash flow is the amount which the owner can take out from the company in the form of dividend or other distributions. It is used for calculating net present value (NPV) of a project, which is an important criterion for future capital expenditure by firms. Furthermore, around 80 per cent of chief financial officers (CFOs) globally and around 65 per cent in India use NPV as a criteria for investment (Anand, 2002; Brealey et al., 2014; Graham and Harvey, 2001). ROA and RCFA are based on historic valuations of assets but some part of total assets could be non-operating. This problem can be overcome by considering ROS or operating profit margin of the firm instead (Barber and Lyon, 1996). Profit margin is unaffected from post-issue increase in assets – used as denominator in some performance indicators. Ratio of sales to total assets, known as TOR, is used to estimate efficiency of assets of a firm. ROA, ROS and TOR are related to each other. Through Du Pont3 analysis, one can ascertain the variable contributing to a firm’s performance measured by ROA (Brealey et al., 2014). Besides these ratios, the study also examines growth rates of sales and capital expenditure as they indicate growth opportunities for the firm. Methodology We use both univariate and multivariate approaches to analyse the change in performance of IPO firms. Change in operating performance is calculated as the median change in performance in post-issue years over the year immediately before issue, i.e., operating performance in year [t] minus operating performance in year [-1], where [t] represents financial year after the issue year. The use of median is preferred over mean because of its relative immunity to extreme values. Industry-adjusted operating performance is adjusted with median firm’s and matched firm’s performance at 5-digit national industrial classification (NIC)4. A matched firm is selected using Mahalanobis5 distance criterion. For the purpose of hypothesis testing, we use the Wilcoxon signed-rank test in line with literature. For ascertaining causes of change in performance, most of the studies have employed ordinary least squares (OLS) regression as the principal technique with retained ownership of owner-manager as an explanatory variable. Such models, however, only show average change in performance without providing information on break-up of change in performance due to IPO and industry trend. This approach also suffers from self-selection and endogeneity. These problems can be addressed to some extent by using difference-in-differences (DID) estimator method (Card and Krueger, 1994; Wooldridge, 2007). We, therefore, use DID method for ascertaining the causal effect of IPOs on firms’ post-issue performance. IPO firms have been used as treatment firms, whereas matched firms have been used as control/comparison firms. To estimate the causal effect using DID method, we estimate the following equation:  Here IPO is the dummy variable for IPO firms; it captures possible difference in operating performance of IPO firms and control firms. d2 is the time dummy; which captures aggregate changes in operating performance in absence of issue. Interaction term d2.IPO is equal to one for issue firms after IPO. Coefficient of d2.IPO is the DID representing effect of IPO on the post-issue operating performance of IPO firms after controlling for the industry effect. Following Mikkelson et al. (1997), Lukose and Rao (2003), Kim et al. (2004), Wang (2005) and Rajan and Zingales (1995), size and debt-equity ratio of firms are used for identifying matching firms. Alternatively, as suggested by Barber and Lyon (1996), firms have also been matched using ROA, size, debt-equity ratio; ROA and size; and, debt-equity ratio, ROA and price to book ratio (PB) of firms. The standard errors of estimates are corrected using cluster robust following Bertrand et al. (2004). Section IV Descriptive Statistics Summary statistics relating to IPO firms are set out in Table 2. Mean (median) issue size of sample firms was ₹2163.0 million (₹584 million). Mean (median) return on the listing day was 20.4 per cent (13.7 per cent), indicating very high underpricing by many firms. Median shareholding of promoters and promoter groups in firms declines to 49.7 per cent post-issuance, from 70.4 per cent prior to issuance which is lower than what has been reported by Jain and Kini (1994) and Mikkelson et al. (1997) in case of the United States (US). Median age of IPO firms was 11 years at the time of issue. | Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of IPO Firms | | Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Min | Max | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | | Offer price (₹) | 139.1 | 164 | 82.0 | 10.0 | 1310.0 | | Size of Issue (₹ Million) | 2163 | 7540 | 584.3 | 15.0 | 98040.0 | | Shareholding of promoter before issue (%) (280) | 69.7 | 22.8 | 70.4 | 10.0 | 100.0 | | Shareholding of promoters after issue (%) (273) | 49.7 | 17.4 | 49.7 | 2.5 | 90.0 | | Age of the firm at the time of IPO (in years)# | 12.0 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 0 | 92.0 | | PE ratio (262) | 100.8 | 761.0 | 14.5 | 0.63 | 10125.0 | #: Age of the firm is difference between issue year and year of incorporation as available in Prowess database.

Notes: i. Promoters post-issue shareholding immediately after the issue; figures in parentheses are number of companies; ii. Calculated by the authors on basis of data collected from prospectuses of IPO firms; iii. Data for promoters’ shareholding and PE ratio has been hand collected from prospectuses of the IPO companies.

Source: CMIE Prowess database. | Section V Univariate Analysis of Operating Performance IPO firms are not able to maintain high ROA post-issuance, however, it remains above the industry median (Table 3). RCFA declines sharply in year [0] but recovers thereafter and converges to industry median indicating a tendency of convergence in IPO firms’ performance with the industry average. IPO firms witness a sharp expansion in capital expenditure and assets size in the post-issue period6. In comparison with matched firms, IPO firms report higher ROA throughout the sample period but somewhat lower RCFA. Median turnover ratio of IPO firms is almost similar to matched firms in the year [-1]; however, it declines post issuance and difference widens in post-issue years. As against asset-scaled variables, ROS – profit scaled by sales – does not show any significant post-issue decline; it remains steady and significantly higher than industry median and the matched firm. Steady ROS is in contrast with the ostensible view that IPO firms’ performance declines post-issuance. The ensuing discussion provides detailed analysis of post-issue change in these indicators. Change in performance is adjusted for industry median and matched firm’s performance. Median change in operating returns of IPO firms post-issuance relative to year [-1] was (-) 3.0 per cent, (-) 4.4 per cent, (-) 5.6 per cent and (-) 6.2 per cent in years [0], [1], [2] and [3], respectively. Industry-adjusted operating returns also showed a similar trend. Median industry-adjusted operating returns in year [0], [1], [2] and [3] vis-à-vis year [-1] declined by 2.5 per cent, 2.7 per cent, 3.9 per cent and 3.5 per cent, respectively (Table 4). Operating performance measured by RCFA also declined during the post-issue period. The decline, however, was muted in the first and the second-year post-issuance and it improved in the third year. Industry median-adjusted and Mahalanobis distance matched firm-adjusted RCFA also showed the same trend in a statistically significant manner indicating that IPO firms do not face post-issue cash flow problems. These results are in contrast with Jain and Kini (1994). | Table 3: Median Values of Important Operating Performance Parameters | | (Per cent) | | Year | IPO Firm | Industry Median | Match Firms’ Median | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | | ROA | | -1 | 15.6 | 10.7 | 10.4 | | 0 | 12.6 | 10.4 | 9.8 | | 1 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 9.5 | | 2 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 9.1 | | 3 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 9.1 | | Ratio of net cash flow with total assets (RCFA) | | -1 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 4.6 | | 0 | -3.3 | 1.8 | 2.9 | | 1 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 4.4 | | 2 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | | 3 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 4.2 | | ROS | | -1 | 18.3 | 14.5 | 13.5 | | 0 | 19.7 | 14.7 | 14.0 | | 1 | 17.6 | 15.0 | 13.3 | | 2 | 16.0 | 14.7 | 13.0 | | 3 | 16.9 | 14.1 | 13.3 | | Turnover Ratio | | -1 | 84.8 | 71.7 | 85.3 | | 0 | 63.6 | 63.2 | 83.3 | | 1 | 60.3 | 87.0 | 74.3 | | 2 | 55.4 | 87.8 | 76.3 | | 3 | 52.7 | 54.5 | 68.8 | | Sales Growth | | -1 | 31.1 | 18.6 | 17.8 | | 0 | 38.1 | 21.8 | 15.1 | | 1 | 21.5 | 13.0 | 7.7 | | 2 | 14.5 | 10.2 | 9.9 | | 3 | 12.0 | 9.6 | 8.7 | | Total Assets Growth | | -1 | 37.5 | 12.3 | 9.9 | | 0 | 65.5 | 14.9 | 10.8 | | 1 | 17.2 | 8.7 | 6.3 | | 2 | 12.8 | 7.1 | 6.0 | | 3 | 10.7 | 5.8 | 3.6 | | Growth of Capital Expenditure | | -1 | 19.8 | 2.6 | | | 0 | 34.0 | 4.4 | 57.4 | | 1 | 22.2 | 1.3 | 34.2 | | 2 | 5.3 | 0.0 | -1.9 | | 3 | 2.1 | -0.3 | 11.3 | Notes: 1. Firms are matched at NIC 5-digit level using total assets and debt equity ratio.

2. PBDITA is operating profit of the firm, i.e., profit before depreciation, interest, taxes and amortisation. ROA is ratio of PBDITA to total assets. ROS is ratio of PBDITA to sales. Turnover ratio is ratio of sales to total assets.

Source: Authors calculation on the basis of CMIE Prowess database. |

| Table 4: Median Change in the Performance Variables over the Year Prior to Issue | | (Per cent) | | Measure of Operating Performance | Financial Year relative to Year [-1] | | From -1 to 0 | From -1 to 1 | From -1 to 2 | From -1 to 3 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | | ROA | | IPO firm | -3.0*** | -4.4*** | -5.6*** | -6.2*** | | Median industry adjusted | -2.5*** | 2.7*** | -3.9*** | -3.5*** | | Match firm adjusted | -2.8*** | -3.9*** | -4.7*** | -5.3*** | | RCFA | | IPO firm | -5.0*** | -1.0 | -0.1 | 1.0* | | Median industry adjusted | -3.0*** | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | | Match firm adjusted | -4.0*** | -1.3 | 0.6 | 3.0* | | Asset turnover ratio | | IPO firm | -19.2*** | -23.3*** | -26.1*** | -26.3*** | | Median industry adjusted | -16.0*** | -17.1*** | -17.7*** | -20.7*** | | Match firm adjusted | -12.6*** | -27.2*** | -27.4*** | -28.1*** | | ROS | | IPO firm | 0.6*** | -0.3 | -1.4*** | -1.1*** | | Median industry adjusted | 0.6*** | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | | Match firm adjusted | 0.01** | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0* | | Sales growth | | IPO firm | 36.3*** | 55.1*** | 70.2*** | 86.9*** | | Median industry adjusted | 14.5*** | 17.1*** | 21.0*** | 24.0*** | | Match firm adjusted | 19.4*** | 34.7*** | 41.1*** | 40.4*** | | Capital Expenditure | | IPO firm | 64.4*** | 94.8*** | 119.4*** | 151.4*** | | Median industry adjusted | 0 | 18.2 | 61.9 | 18.4 | | Match firm adjusted | -9.7 | 70.9*** | 80.2 | 44.6*** | *, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively.

Notes: 1. Change for year [t] is calculated as difference of performance in year [t] and performance in year [-1]. Issue year is used as the base year, i.e. year [0].

2. Test of significance is based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Source: Authors calculation based on Prowess database. | Interestingly, though change in ROS was negative for IPO firms, adjusted ROS - for industry median as well as matched firms - did not show any decline; in fact, it increased marginally in year [3] post-issuance. IPO firms maintained higher sales growth post-issue vis-à-vis industry median and also higher growth in capital expenditure (Table 4). Nevertheless, IPO firms witnessed decline in the asset turnover ratio suggesting that issue firms were not able to exploit their assets fully. As univariate results are not controlled for confounding variables, we conduct a multivariate analysis, controlling for firms’ sales promotion expenditures, R&D expenses, short-term liquidity, business group affiliations, promoters’ ownership, and executive directors’ ownership. Section VI Multivariate Analysis For multivariate analysis, we use difference-in-differences (DID) approach to estimate the impact of IPO on firms’ post-issue performance relative to pre-issue period, using operating returns as dependent variable. In addition to a dummy for IPO, year dummies and interaction terms [IPO dummy × Year dummy], we use control variables such as size of firm, advertisement intensity, R&D intensity, slack ratio and retained shareholding of promoters of the firm post-issue. Logarithm of sales is used as a proxy for size of the firm. Advertisement, R&D intensity and slack variables are taken as ratios to total sales of the firm. Slack is calculated as difference between current assets and current liabilities of a firm. Advertisement intensity and R&D intensity indicate firm’s efforts to augment its operations, while slack indicates availability of liquidity. Results indicate a consistent decline in ROA in the three years post-issuance compared to the matched firms. TOR also shows a similar decline. RCFA, however, shows decline only in the first-year post-issuance. The decline in ROS is statistically insignificant7. It may, thus, be concluded that the primary reason for the decline in the operating performance is increase in assets of an IPO firm (Table 5). Theoretical prepositions, such as agency theory and entrenchment theory are tested in the Indian context using multivariate regressions. To test agency cost, we regress ROA, RCFA, TOR and ROS on promoters’ retained shareholding in firm. We also regress change in performance of firm i in year [t] relative to year [–1] on promoters’ residual ownership. Regressions are controlled by advertisement intensity, R&D ratio, slack ratio, ownership group dummy and family firm dummy (Tables 6, 7, 8 and 9). Promoters’ retained shareholding has a positive and statistically significant coefficient for ROA and RCFA. However, its impact on TOR and ROS is statistically insignificant. Thus, the results are inconclusive to either reject or support agency relationship hypothesis. Following Jain and Kini (1994) and Kim et al. (2004), change in operating ratios were regressed over retained shareholdings of the promoters; none of the coefficients were found to be statistically significant (Table 10). | Table 5: Difference-in-differences (DID) Estimates of IPO Firms’ Performance after IPO | | Dependent Variables | ROA | ROS | TOR | RCFA | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | | IPO | 0.0430*** | -2.2242 | -0.1264 | -0.0158 | | | (0.012) | (2.004) | (0.118) | (0.014) | | Year[0] | -0.0145 | -2.1257 | -0.0908** | 0.0079 | | | (0.009) | (2.082) | (0.042) | (0.013) | | Year[1] | -0.0285*** | -2.2585 | -0.0925*** | 0.0085 | | | (0.009) | (2.070) | (0.029) | (0.012) | | Year[2] | -0.0195 | -2.2198 | -0.1285*** | 0.0061 | | | (0.014) | (2.069) | (0.042) | (0.014) | | Year[3] | -0.0339*** | -2.3409 | -0.1840*** | 0.0080 | | | (0.009) | (2.072) | (0.068) | (0.011) | | IPO× Year[0] | -0.0381*** | 2.9460 | -0.2308*** | -0.0813*** | | | (0.012) | (2.256) | (0.043) | (0.017) | | IPO× Year[1] | -0.0498*** | 3.6323 | -0.2922*** | -0.0253 | | | (0.013) | (2.524) | (0.038) | (0.016) | | IPO× Year[2] | -0.0744*** | 2.1755 | -0.2960*** | -0.0123 | | | (0.017) | (2.292) | (0.045) | (0.017) | | IPO× Year[3] | -0.0802*** | 2.8112 | -0.2702*** | -0.0009 | | | (0.020) | (2.487) | (0.064) | (0.015) | | Log of sales | 0.0191*** | | 0.1342*** | 0.0088*** | | | (0.004) | | (0.020) | (0.002) | | Ad intensity | 0.0012 | 17.7388*** | 0.0057 | 0.0024*** | | | (0.001) | (0.112) | (0.004) | (0.001) | | R&D ratio | -0.0020 | -2.2038* | -2.5829*** | 0.0137 | | | (0.140) | (1.225) | (0.488) | (0.119) | | Slack ratio | -0.0000 | 0.0275 | -0.0000 | -0.0000 | | | (0.000) | (0.026) | (0.000) | (0.000) | | Constant | 0.0133 | 3.9361 | 0.2673*** | -0.0153 | | | (0.024) | (4.048) | (0.058) | (0.014) | | Observations | 3,086 | 3,086 | 3,086 | 2,933 | | R-squared | 0.108 | 0.631 | 0.106 | 0.060 | Notes: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively.

1. IPO is treatment dummy indicating that firm is an IPO firm. Year[t]s are time dummies, while IPO× Year[t]s are interaction between IPO dummy and time dummies.

2. Year dummies are proxies for year [0], [1], [2] and [3] post-issuance.

3. IPO×Year[t]s are interaction terms for treatment and year dummies.

4. Ad intensity, R&D ratio and slack ratio have been calculated as ratio of advertisement expenditure, R&D expenditure and slack (current assets – current liabilities) with sales. |

| Tables 6: Regression Results of ROA | | Variables/ specifications | I | II | III | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | | Shares held by Promoters | 0.0008*** | 0.0010*** | 0.0010*** | | | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | | Log of Sales | 0.0204*** | 0.0234*** | 0.0234*** | | | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | | Ad Intensity | 0.0020** | 0.0035*** | 0.0036*** | | | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | | R&D Ratio | 0.231 | 0.142 | 0.171 | | | (0.371) | (0.390) | (0.388) | | Slack Ratio | -<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | | | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | | Ownership Dummy | | 0.0430*** | 0.0442*** | | | | (0.014) | (0.014) | | Family Firms | | | -0.00646 | | | | | (0.010) | | Constant | -0.117*** | -0.189*** | -0.186*** | | | (0.036) | (0.049) | (0.048) | | Observations | 832 | 832 | 832 | | R-squared | 0.299 | 0.327 | 0.328 | | Industry Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | | Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Notes: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively.

1. Controlling variables are advertising intensity (ratio of advertisement expense with sales), R&D ratio (ratio of R&D expenses with sales), slack ratio (ratio of slack with sales. Slack = current assets – current liabilities) and log of sales.

2. Ownership dummy = 1, if IPO firm does not belong to a business group, which pre-owns a listed firm.

3. Family firm dummy = 1, if one or more than one executive directors of firm are also promoters of the firm. |

| Table 7: Regression Results of RCFA | | Variables/ specifications | I | II | III | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | | Shares held by Promoters | 0.0012*** | 0.0012*** | 0.0013*** | | | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | | Log of Sales | 0.0099** | 0.0106** | 0.0104** | | | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | | Ad Intensity | 0.0034*** | 0.0038*** | 0.0039*** | | | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | | R&D Ratio | 0.6760** | 0.6550** | 0.703** | | | (0.273) | (0.277) | (0.279) | | Slack Ratio | -<0.001 | -(<0.001 | -(<0.001 | | | (<0.001) | ((<0.001) | ((<0.001) | | Ownership Dummy | | 0.0101 | 0.0120 | | | | (0.015) | (0.015) | | Family Firms | | | -0.010 | | | | | (0.0105) | | Constant | -0.241*** | -0.258*** | -0.253*** | | | (0.047) | (0.056) | (0.054) | | Observations | 827 | 827 | 827 | | R-squared | 0.215 | 0.216 | 0.218 | | Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | | Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Notes: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively.

1. Controlling variables are advertising intensity (ratio of advertisement expense with sales), R & D ratio (ratio of R&D expenses with sales), slack ratio (ratio of slack with sales. Slack = current assets – current liabilities) and log of sales.

2. Ownership dummy = 1, if IPO firm does not belong to a business group, which pre-owns a listed firm.

3. Family firm = 1, if one or more than one executive directors of firm are also promoters of the firm. |

| Table 8: Regression Results of TOR | | Variables / specifications | I | II | IIII | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | | Shares held by Promoters | 0.0021 | 0.0021 | 0.0022 | | | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | | Log of Sales | 0.147*** | 0.149*** | 0.149*** | | | (0.035) | (0.032) | (0.032) | | Ad Intensity | 0.0139* | 0.0150** | 0.0154** | | | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.008) | | R&D Ratio | -5.061 | -5.125 | -4.984 | | | (3.57) | (3.58) | (3.52) | | Slack Ratio | -(<0.001) | -(<0.001) | -(<0.001) | | | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | | Ownership Dummy | | 0.0313 | 0.0373 | | | | (0.107) | (0.108) | | Family Firms | | | -0.0318 | | | | | (0.062) | | Constant | 0.346 | 0.293 | 0.308 | | | (0.402) | (0.387) | (0.381) | | Observations | 832 | 832 | 832 | | R-squared | 0.452 | 0.453 | 0.453 | | Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | | Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Note: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively. |

| Table 9: Regression Results of ROS | | Variables/ specifications | I | II | III | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | | Shares held by Promoters | 0.0263 | 0.0163 | 0.0132 | | | (0.0214) | (0.0167) | (0.0160) | | Ad Intensity | 17.75*** | 17.70*** | 17.67*** | | | (0.0670) | (0.101) | (0.120) | | R&D Ratio | 0.297 | 4.494 | -3.702 | | | (3.955) | (6.788) | (6.918) | | Slack Ratio | 0.0297 | 0.0297 | 0.0297 | | | (0.0265) | (0.0263) | (0.0263) | | Ownership Dummy | | -3.145 | -3.526 | | | | (2.390) | (2.683) | | Family Firms | | | 1.909 | | | | | (1.631) | | Constant | -1.369 | 2.319 | 1.588 | | | (1.456) | (1.933) | (1.554) | | Observations | 832 | 832 | 832 | | R-squared | 0.823 | 0.824 | 0.825 | | Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | | Time Fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Note: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively. |

| Table 10: Regression of change in ROA and RCFA over retained ownership of promoters | | Variables/ specifications | ROA | RCFA | | 1 | 2 | 3 | | Promoters’ shareholding | -0.0002 | 0.0002 | | | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | | Age | 0.0001*** | 0.0003 | | | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | | Log of sales | 0.0020 | 0.0006 | | | (0.002) | (0.002) | | Constant | -0.0180 | -0.0182 | | | (0.021) | (0.022) | | Observations | 1,306 | 1,266 | | | 264 | 264 | | R-squared | 0.037 | 0.023 | Note: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively. | Following Mikkelson et al. (1997), managerial entrenchment was measured by residual personal holdings of members of board of directors retained post issuance. Regression results indicate statistically insignificant coefficient of the management ownership which are in line with Mikkelson et al. (1997). Alternatively, following Kim et al. (2004), we replaced personal shareholding of directors/managers of the firm with overall shareholding of the promoters but does not find statistically significant results. Thus, our findings do not support entrenchment hypothesis either (Table 11). As regression results on agency relationship and entrenchment hypotheses were inconclusive, we matched control firms using ROA within the same industry at 2-digit NIC8. Decline in ROA was substantially muted when IPO firms were matched with the same operating variable (Table 12). | Table 11: Regression Results of Entrenchment Hypothesis Testing | | Variables/ specifications | ROA | ROS | RCFA | TOR | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | | Executive Directors’ share | 0.00165 | 0.00830 | -0.000697 | 0.00395 | | | (0.00128) | (0.0527) | (0.00126) | (0.00861) | | Executive Directors’ share^2 | -<0.001 | -<0.001 | <0.001 | -<0.001 | | | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | | Executive Directors’ share^3 | <0.001 | -<0.001 | -<0.001 | -<0.001 | | | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | | Advertising Intensity | 0.00154* | 17.76*** | 0.00361*** | 0.0126 | | | (0.000875) | (0.0606) | (0.000911) | (0.00810) | | R&D Ratio | 0.573 | 3.136 | 0.581 | -6.115* | | | (0.434) | (5.105) | (0.429) | (3.297) | | Slack Ratio | -<0.001 | 0.0295 | -<0.001 | -<0.001 | | | (<0.001) | (0.0264) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | | Log of Sales | 0.0194*** | | 0.0102** | 0.144*** | | | (0.00385) | | (0.00402) | (0.0323) | | Constant | -0.0528 | -0.383 | -0.151*** | 0.682* | | | (0.0385) | (0.756) | (0.0457) | (0.378) | | Observations | 1,047 | 1,047 | 1,036 | 1,047 | | R-squared | 0.256 | 0.822 | 0.138 | 0.425 | | Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | | Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Note: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively. | This indicates that decline in performance of high-performance firms is rather a common phenomenon and not limited to IPO firms only. | Table 12: DID Results when IPO Firms are Matched by ROA at NIC 2-digit | | Variables | ROA | ROS | TOR | RCFA | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | | IPO | 0.0127 | -0.6979* | -0.1286 | -0.0535*** | | | (0.009) | (0.419) | (0.084) | (0.012) | | Year[0] | -0.0131 | -0.2158 | -0.1070* | -0.0084 | | | (0.017) | (0.505) | (0.060) | (0.017) | | Year[1] | -0.0244*** | 0.4854 | -0.1626*** | -0.0156 | | | (0.008) | (0.512) | (0.062) | (0.012) | | Year[2] | -0.0366*** | -0.0968 | -0.2062*** | -0.0377*** | | | (0.007) | (0.829) | (0.065) | (0.011) | | Year[3] | -0.0368*** | -0.3905 | -0.2355*** | -0.0223** | | | (0.007) | (0.532) | (0.067) | (0.009) | | IPO*Year[0] | -0.0391** | 0.6570 | -0.1924*** | -0.0738*** | | | (0.018) | (0.613) | (0.065) | (0.019) | | IPO*Year[1] | -0.0515*** | 0.4859 | -0.1868*** | -0.0020 | | | (0.011) | (1.036) | (0.068) | (0.015) | | IPO*Year[2] | -0.0526*** | -0.0979 | -0.1650** | 0.0332** | | | (0.011) | (0.850) | (0.072) | (0.014) | | IPO*Year[3] | -0.0665*** | 0.7167 | -0.1650** | 0.0254* | | | (0.015) | (0.903) | (0.073) | (0.014) | | Log of Sales | 0.0164*** | -0.2826 | 0.1161*** | 0.0094*** | | | (0.003) | (0.315) | (0.009) | (0.001) | | Slack Ratio | -0.0000 | 0.0281 | -0.0000 | -0.0000 | | | (0.000) | (0.025) | (0.000) | (0.000) | | R&D Ratio | -0.1284 | -8.0130 | -3.4464*** | -0.2501 | | | (0.180) | (5.282) | (0.713) | (0.210) | | Advertisement Ratio | 0.0001 | 16.7633*** | 0.0004 | 0.0017 | | | (0.001) | (0.264) | (0.003) | (0.001) | | Constant | 0.0580*** | 2.0273 | 0.3802*** | 0.0218* | | | (0.020) | (2.195) | (0.087) | (0.012) | | Observations | 3,423 | 3,423 | 3,423 | 3,288 | | R-squared | 0.089 | 0.714 | 0.170 | 0.079 | Note: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses.

*, **, ***: Indicates significance at 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels, respectively. | Section VII Conclusion This study revisited the post-issue performance of IPO firms in India. One distinct feature of the study vis-à-vis earlier studies is that instead of confining to asset-scaled performance variables, it also analysed variables scaled by sales. In addition to return on assets and ratio of operating cash flow to total assets, it analysed turnover ratio, return on sales and growth of sales to assess the performance. The analysis indicated that the post-issue operating performance of IPO firms measured as return on asset and turnover ratio recorded a sharp decline. However, contrary to the findings of extant literature, we found that the decline in ratio of operating cash flow to total assets was confined to the issue year and year after the issue only. Initial decline in the ratio of operating cash flow to total assets could be on account of enlarged capital expenditures, which firms resort to after the IPO. We also found that return on sales and sales growth didn’t show a statistically significant change after issue. The study also found that IPO firms continue to outperform matched firms from the same industry when compared in terms of change in relevant operating variables. A battery of tests conducted after controlling for firms’ various attributes such as family-control, business group ownership, size, R&D expenditure, advertisement expenditure and liquidity, indicated that decline in performance could not be completely explained by agency relationship and entrenchment hypothesis. We also found that the major cause for decline in asset-scaled operating ratios after an IPO was sharp expansion of the balance sheet size (more than industry average) and consequential increase in assets of IPO firms. Therefore, normalisation of the operating performance variables by sales rather than assets would be more appropriate.

References Anand, M. (2002). Corporate finance practices in India: a survey. Vikalpa, 27(4), 29-56. Balatbat, M. C., Taylor, S. L., & Walter, T. S. (2004). Corporate governance, insider ownership and operating performance of Australian initial public offerings. Accounting & Finance, 44(3), 299-328. Barber, B. M., & Lyon, J. D. (1996). Detecting abnormal operating performance: The empirical power and specification of test statistics. Journal of financial Economics, 41(3), 359-399. Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates?. The Quarterly journal of economics, 119(1), 249-275. Bhatia, S., & Singh, B. (2013). Ownership Structure and Operating Performance of IPOs in India. The IUP Journal of Applied Economics, 12(3), pp. 7–37. Brav, A., & Gompers, P. A. (1997). Myth or reality? The long-run underperformance of initial public offerings: Evidence from venture and nonventure capital-backed companies. The Journal of Finance, 52(5), 1791-1821. Brealey, R. A., Myers, S. C., Allen, F., & Mohanty, P. (2014). Principles of corporate finance. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. Bruton, G. D., Filatotchev, I., Chahine, S., & Wright, M. (2010). Governance, ownership structure, and performance of IPO firms: The impact of different types of private equity investors and institutional environments. Strategic management journal, 31(5), 491-509. Cai, J., & Wei, K. J. (1997). The investment and operating performance of Japanese initial public offerings. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 5(4), 389-417. Card, D., & Krueger, A. B. (1994). Minimum wages and employment: a case study of the fast-food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The American Economic Review, 84(4), 772-793. Chahine, S. (2007). Block-holder ownership, family control and post-listing performance of French IPOs. Managerial Finance, 33(6), 388-400. Chen, A., & Kao, L. (2005). The conflict between agency theory and corporate control on managerial ownership: The evidence from Taiwan IPO performance. International Journal of Business, 10(1), 39. Fan, J. P., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. (2007). Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. Journal of financial economics, 84(2), 330-357. Ghosh, S. (2005). The post-offering performance of IPOs in the Indian banking industry. Applied Economics Letters, 12(2), 89-94. Goswami, O. (2001). The tide rises, gradually: corporate governance in India. Development Centre discussion paper. Graham, J. R., & Harvey, C. R. (2001). The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. Journal of financial economics, 60(2-3), 187-243. Helwege, J., & Liang, N. (2004). Initial public offerings in hot and cold markets. Journal of financial and Quantitative Analysis, 39(3), 541-569. Ibbotson, R. G. (1975). Price performance of common stock new issues. Journal of financial economics, 2(3), 235-272. Jain, B. A., & Kini, O. (1994). The post-issue operating performance of IPO firms. The journal of finance, 49(5), 1699-1726. Janakiramanan, S. (2008). Under-pricing and long-run performance of initial public offerings in Indian stock market. National Stock Exchange of India Research Papers, NSE, 18106, 1. Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of financial economics, 3(4), 305-360. Kao, J. L., Wu, D., & Yang, Z. (2009). Regulations, earnings management, and post-IPO performance: The Chinese evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(1), 63-76. Kim, K. A., Kitsabunnarat, P., & Nofsinger, J. R. (2004). Ownership and operating performance in an emerging market: evidence from Thai IPO firms. Journal of corporate Finance, 10(3), 355-381. Kohli, V. (2009). Do stock markets allocate resources efficiently? An examination of initial public offerings. Economic and Political Weekly, 63-72. Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of accounting and economics, 39(1), 163-197. Kutsuna, K., Okamura, H., & Cowling, M. (2002). Ownership structure pre-and post-IPOs and the operating performance of JASDAQ companies. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 10(2), 163-181. Krishnan, C. N. V., Ivanov, V. I., Masulis, R. W., & Singh, A. K. (2011). Venture capital reputation, post-IPO performance, and corporate governance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46(5), 1295-1333. Kurtaran, A., & Er, B. (2008). The post-issue operating performance of IPOs in an emerging market: evidence from Istanbul Stock Exchange. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 5(4), 50-62. Leland, H. E., & Pyle, D. H. (1977). Informational asymmetries, financial structure, and financial intermediation. The journal of Finance, 32(2), 371-387. Loughran, T., & Ritter, J. R. (1995). The new issues puzzle. The Journal of finance, 50(1), 23-51. Lukose, P. J., & Rao, S. N. (2003). Operating performance of the firms issuing equity through rights offer. Vikalpa, 28(4), 25-40. Lyandres, E., Sun, L., & Zhang, L. (2007). The new issues puzzle: Testing the investment-based explanation. The Review of Financial Studies, 21(6), 2825-2855. Marisetty, V. B., & Subrahmanyam, M. G. (2010). Group affiliation and the performance of IPOs in the Indian stock market. Journal of Financial Markets, 13(1), 196-223. Mayur, M. (2013). Agency Problems and Operating Performance in an Emerging Market: Evidence from Indian IPOs. Mayur, M., & Mittal, S. (2014). Relationship between Underpricing and Post IPO Performance: Evidence from Indian IPOs. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 10(2), 129-136. Michel, A., Oded, J., & Shaked, I. (2014). Ownership structure and performance: Evidence from the public float in IPOs. Journal of Banking & Finance, 40, 54-61. Mikkelson, W. H., Partch, M. M., & Shah, K. (1997). Ownership and operating performance of companies that go public. Journal of financial economics, 44(3), 281-307. Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1988). Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. Journal of financial economics, 20, 293-315. Pagano, M., Panetta, F., & Zingales, L. (1998). Why do companies go public? An empirical analysis. The Journal of Finance, 53(1), 27-64. Pástor, Ľ., Taylor, L. A., & Veronesi, P. (2008). Entrepreneurial learning, the IPO decision, and the post-IPO drop in firm profitability. The Review of Financial Studies, 22(8), 3005-3046. Pereira, T. P., & Sousa, M. (2017). Is there still a Berlin Wall in the post-issue operating performance of European IPOs?. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 22(2), 139-158. Rindermann, G. (2004). Venture capitalist participation and the performance of IPO firms: empirical evidence from France, Germany, and the UK. Ritter, J. R. (1984). The” hot issue” market of 1980. Journal of Business, 215-240. Ritter, J. R. (1987). The costs of going public. Journal of Financial Economics, 19(2), 269-281. Ritter, J. R. (1991). The long-run performance of initial public offerings. The journal of finance, 46(1), 3-27. Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1989). Management entrenchment: The case of manager-specific investments. Journal of financial economics, 25(1), 123-139. Wang, C. (2005). Ownership and operating performance of Chinese IPOs. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(7), 1835-1856. Wooldridge, J. M. (2007). Pooling cross-sections across time: Simple panel data methods. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western. Young, M. N., Peng, M. W., Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G. D., & Jiang, Y. (2008). Corporate governance in emerging economies: A review of the principal–principal perspective. Journal of management studies, 45(1), 196-220.

Annex: Survey of Extant Literature on Post-Issue Operating Performance of IPO Firms | Sr. No | Title and year of publication | Country | Author(s) | Main Hypothesis | Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Principal Conclusions | | 1 | 2 | | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | | 1 | The Post-Issue Operating Performance of IPO Firm (1994) | US | Bharat A. Jain & Omesh Kini | Positive relationship between post-issue operating performance and retained ownership of original entrepreneurs. | Return on asset, ratio of net operating cash flow with total assets. | Retained ownership, under-pricing, and MV and PE ratio. | Linear relationship between retained ownership of original entrepreneur and firm’s post-issue operating performance. | | 2 | Ownership and Operating Performance of Companies that go Public (1997) | US | Wayne H. Mikkelson, M. Megan Partch, Kshitij Shah | Post IPO long-run operating performance of firms. | Industry-adjusted operating performance. Operating performance was measured by ROA and industry-adjusted ROA. | Change in officers’ and directors’ stake, majority corporate block-holder, venture capital backing, fraction of outside board of directors at the offering, secondary sales of shares, size and age of firm | Post-issue performance of IPO firms is unrelated to ownership of officers and directors. | | 3 | The Investment and Operating Performance of Japanese Initial Public Offerings (1997) | Japan | Jun Cai, K.C. John Wei | Positive relationship between ownership structure and post-issue performance. | Long-run stock performance. | Size, ownership share of owner-manager, growth of size. | Deterioration of operating performance cannot be attributed to reduced managerial ownership. IPO firms follow window of opportunity while going public. | | 4 | Ownership structure pre-and post-IPOs and the Operating Performance of JASDAQ Companies (2002) | Japan | Kenji Kutsuna, Hideo Okamura, Marc Cowling | Positive relationship between post-issue performance and retained ownership of owner-manager. | Net sales, ordinary profit, net profit and their respective profits (data five years prior to issue and four years post issue have been used). | Change in shareholding, year and sector dummy, age, firm size, market capitalization. | Operating performance varies according to managerial ownership, in addition to the age and size of the firm. | | 5 | Operating Performance of the Firms Issuing Equity through Rights Offer (2003) | India | P.J. Jijo Lukose, S. Narayan Rao | Study examines post-rights’ issue performance of firms. It tests relationship between firm size, ownership and directors’ share in the company. | Cash flow variables like Jain and Kini (1994). | Ownership group, promoters’ share, asset size, age, leverage, year dummy, etc. | The decline in performance is due to inefficiency in utilization of assets and not due to decrease in profit margins. | | 6 | Ownership and Operating Performance in an Emerging Market: Evidence from Thai IPO Firms (2004) | Thailand | Kenneth A. Kim, Pattanaporn Kitsabunnara, John R. Nofsinger | Relationship between post-issue ownership of firm and operating performance. | Operating return on total assets (EBIT/ TA), operating cash flow (CF/TA), sales to total assets ratio and capital expenditure. | Industry-adjusted EBIT/TA (measured as our post-IPO sample EBIT/TA less the industry median EBIT/TA, ownership share along with quadratic and cubic terms. | A curvilinear relationship between managerial ownership and the post-IPO change in performance. | | 7 | Initial Public Offerings in Hot and Cold Markets (2004) | US | Jean Helwege, Nellie Liang | | Industry-adjusted ROA | Pre- and post-issue performance by matching of industry firms | | | 8 | Corporate Governance, Insider Ownership and Operating Performance of Australian Initial Public Offerings (2004) | Australia | M.C. Balatbat, S.L. Taylor, T.S. Walter | Relationship between institutional ownership and post-issue performance. | Matched firm- adjusted ROA. | Ownership structure, board structure and leverage. | No relationship between block- holder ownership and performance. | | 9 | The Post- Offering Performance of IPOs in the Banking Industry (2005) | India | Saurabh Ghosh | Post-IPO long-run underperformance of Indian banks. | Buy and hold return, profitability and efficiency indicators. | ROA, operating profit, interest income, non-performing assets (NPAs), profit per employee, capital adequacy ratio and size. | Due to various macroeconomic and regulatory changes Indian banks did not underperform after IPO. | | 10 | Ownership and Operating Performance of Chinese IPOs (2005) | China | Changyun Wang | Positive relationship between ownership structure and post- issue performance. | ROA, operating income and sales to assets. | Size, age, share of legal owner and leverage. | Neither state ownership nor concentration of ownership is associated with performance changes, however, there is a curvilinear relation between legal entity ownership and performance changes (legal entity ownership?). | | 11 | The Conflict Between Agency Theory and Corporate Control on Managerial Ownership: The Evidence from Taiwan IPO Performance (2005) | Taiwan | Anlin Chen, Lanfeng Kao | Positive relationship between operating performance and institutional ownership and stock performance and managerial ownership. Stock performance is positively related to operating performance. | Annualised stock return and ROA. | Institutional share ownership, managerial ownership and shares owned by the directors. | Linear relationship between retained ownership of pre- offering shareholder and firm’s post- issue operating performance. | | 12 | Block-holder Ownership, Family Control and Post-Listing Performance of French IPOs (2007) | France | Salim Chahine | Examines entrenchment hypothesis in presence of family control. | Buy and hold excess return (BHER) and buy and hold abnormal return in first year after listing. | Ownership share of controlling family, block holder and venture capital. | Firm performance has cubic relationship with ownership of controlling family, negative relationship with block-holder ownership and no significant relationship venture capital ownership. | | 13 | The Post-issue Operating Performance of IPOs in an Emerging Market: evidence from Istanbul Stock Exchange (2008) | Turkey | Ahmet Kurtaran, Bunyamin Er | Post-issue operating performance of firms decline and there is a positive linear relationship between firm’s performance and retained ownership share. | Operating performance such as sales, operating profit, operating cash flow/total assets. | Ownership, age, size, under-pricing. | Findings are in line with Jain and Kini (1994). | | 14 | Venture Capital Reputation, Post-IPO Performance and Corporate Governance (2009) | US | C. N. V. Krishnan, Vladimir I. Ivanov, Ronald W. Masulis, Ajai K. Singh | Presence of venture capital (VC) in IPO firm should manifest in the long run, superior post-IPO performance. | ROA, market-to- book equity ratio, listing survival, long- run abnormal stock returns. | Venture Capital’s (VC) reputation and firm-specific variables. Dummy variable for presence or absence of VC in IPO firms, under- writers’ reputation index, natural log of offer size, issuer’s MV ratio, industry and year fixed effects, age of VC. | Association of venture capital has positive relationship with post-issue performance; VC’s reputation is also positively associated with post-issue performance. | | 15 | Entrepreneurial Learning, the IPO Decision, and the Post-IPO Drop in Firm Profitability (2009) | US | Lubos Pastor, Lucian A. Taylor, Pietro Veronesi | Firm’s profitability should decline after going public. | Return on equity for robustness, return on asset. | Price reaction after earnings announcement. | Decline of performance is sharper in those firms where earnings volatility is higher. | | 16 | Do Stock Market allocate Resources Efficiently? An Examination of Initial Public Offerings (2009) | India | Vineet Kohli | IPO firms underperform compared to non- IPO firms. | Similar variables as used by Jain and Kini (1994). | Industry performance | Financially weak firms go for public issue while financially strong firms go for bank debt. | | 17 | Regulations, Earnings Management, and Post-IPO Performance: The Chinese Evidence (2009) | China | Jennifer L. Kao, Donghui Wu, Zhifeng Yang | Regulation, earnings management and post-issue performance. | ROA and first-day stock return. | Various firm-level variables and regulation dummies. | Due to pricing regulation, IPO firms inflate their earnings and that leads to lower post-issue performance. | | 18 | Governance, Ownership Structure, and Performance of IPO Firms: The Impact of Different Types of Private Equity Investors and Institutional Environments (2010) | UK, France | Garry D. Bruton, Igor Filatotchev, Salim Chahine, Mike Wright | Multiple agency theory | Percentage price premium (defined as (offer price - book value per share)/ offer price), which observes investors optimism about future value of the IPO firms. ROA measured at the end of the IPO year. | Ownership concentration as a Herfindahl- Hirschman Index (HHI) of retained ownership of block holders, share of VC and business angels in post- issue shareholding and dummy and interaction variables for country-specific institutional differences. | Support for the agency theory argument that concentrated ownership improves IPOs’ performance. | | 20 | Is there still a Berlin Wall in the post-issue operating performance of European IPOs (2017) | European countries | Tiago P. Pereira, Miguel Sousa | Post-issue operating underperformance of firms varies across geographies. | Operating performance in line with Jain and Kini (1994). | | Performance of firms located in emerging economies is worse than that of firms located in advance economies. | | 21 | Agency Problems and Operating Performance in an Emerging Market: Evidence from Indian IPOs (2013) | India | Manas Mayur | No relationship between promoters’ share ownership and operating performance. Tests quadratic and cubic relationship between promoters’ ownership and performance. | Operating return on total assets (EBIT/ TA) and operating cash flow (CF/TA) | Promoter directors’ share in the firm | Curvi-linear relationship between post-issue performance and retained ownership of owner-managers | | 22 | Ownership structure and operating performance of IPOs in India (2013) | India | Shikha Bhatia, Balwinder Singh | Relationship between ownership structure and post- issue performance. | ROA, ROE, etc. | Ownership share. Controlled by age, size, leverage and capital expenditure. | Post-issue IPO firms’ performance decline. | | 23 | Ownership Structure and Performance: Evidence from Public Float in IPOs (2014) | US | Allen Michel, Jacob Oded, Israel Shaked | Relationship between IPO firm’s post-issue performance and public float of firm’s shares | ROA | Public float | Non-linear relationship between public float and long- run return | | 24 | Intended Use of Proceeds and the Post-Issue Operating Performance of IPO Firms: A quantile regression approach (2013) | Indonesia | Andriansyah Andriansyah, & George Messinis | Relationship between intended use of issue proceeds and IPO firms’ performance. | ROA, NI/TA and net sales/TA. | Intended use of issue proceeds. | |

|