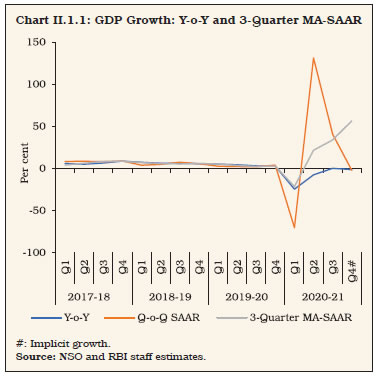

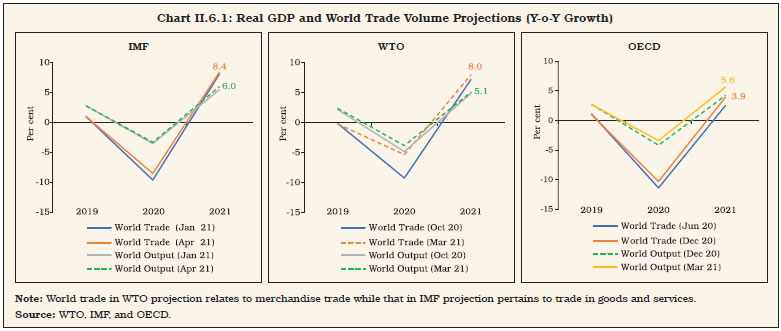

India joined the global economy in an unprecedented contraction in 2020-21, dragged down by the COVID-19 pandemic. Headline inflation was elevated for most part of the year led by supply chain disruptions due to the pandemic and spikes in key food prices. Inflation, however, moderated subsequently due to seasonal easing in food prices since December 2020, albeit with an upside push from adverse base effects during February-March 2021. Monetary and credit conditions remained expansionary and financial market conditions eased considerably on the back of abundant liquidity. Public finances were impacted by a cyclical slowdown in revenues, which was exacerbated by COVID-19, while pandemic-induced fiscal measures pushed up expenditure. On the external front, the sizeable contraction in imports relative to exports, under deep recessionary conditions, led to a current account surplus; along with robust net capital inflows, this led to a large build-up of foreign exchange reserves. II.1 THE REAL ECONOMY II.1.1 In 2020, the global economic sky was overcast with COVID-19 - a virus of the size of 0.12 microns. By end-March 2021, the virus had resulted in over 128 million infections and over 2.8 million mortalities worldwide. The year 2021 has commenced with both hope and fear - several parts of the world are locking down and bracing against new waves of infections and speedily communicable mutations. At the same time, the approval of several vaccines has spurred vaccination drives worldwide, albeit at different speeds. Nearly 600 millions of vaccine doses have already been administered (March 31, 2021), even as vaccine producers struggle to tweak vaccines to keep pace with mutations. In the event, 2020 has gone down in human history as the year of the ‘Great Lockdown’1, with output losses dwarfing those suffered during the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-09. World trade declined by around 8.5 per cent, with the contraction in services trade outpacing the fall in merchandise trade. II.1.2 The year 2020 will also be memorable for unprecedented policy responses which, although not coordinated, turned out to be synchronised. A slew of conventional and unconventional measures was unleashed across the world, with monetary authorities slashing policy rates to zero and below in real terms - and even in nominal terms in some countries - while executing massive asset purchase programmes, payment deferral schemes, provision of public guarantees, emergency funding avenues and provision of ample liquidity to financial markets. The stimulus provided by fiscal authorities was equally unprecedented in scale and scope, amounting to US$ 16 trillion2 (15.3 per cent of the GDP). Of the total amount, US$ 10 trillion consisted of additional spending or foregone revenue, while US$ 6 trillion comprised liquidity support in the form of guarantees, loans, asset/debt purchases, and equity injections. This policy fightback led to a massive easing of financial conditions and imparted stability to the financial system, thereby containing downside risks to growth. II.1.3 Equity markets, in particular, have recovered exuberantly from the panic that set in when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020. Cyclical stocks3 have led the rally, driven by optimism surrounding the arrival of vaccines and fresh rounds of fiscal stimulus in major economies. Crude oil prices and other commodity prices are also firming up on the back of these positive developments, with production restraints by the organisation of the petroleum exporting countries (OPEC) providing added momentum in February and March 2021 and creating conditions for the forming of a new commodity super-cycle. II.1.4 The agglutination of supply disruptions, the health crisis, an unparalleled mass migration and a hostile global environment took a heavy toll on the Indian economy. A cyclical slowdown had preceded the pandemic, causing real gross domestic product (GDP) growth to register a sequential deceleration since 2017-18, which slumped into contraction under the onslaught of COVID-19. Within two weeks of the World Health Organisation (WHO) declaring it a pandemic, India imposed a strict lockdown. The combination of demand compression and supply disruption that took hold in its wake caused severe debilitating effects on the economy in Q1:2020-21. By mid-September, the total number of COVID-19 cases crossed 50 lakh - the second highest caseload in the world, with over 0.8 lakh fatalities. It was a turning point, however; thereon, India bent the COVID-19 curve, with the seven-day rolling average of new confirmed cases dropping from 93,199 on September 16, 2020 to 11,145 on February 11, 2021 before rising sharply thereafter (62,019 on March 31, 2021). By the end of March 2021, the recovery rate was around 94 per cent and the number of active cases had surged to 5.8 lakh. II.1.5 With gradual lifting of restrictions and reopening of the economy, the pace of contraction moderated in Q2 and GDP returned to positive terrain in Q3 of 2020-21. Sensing the recovery gaining traction, equity markets became ebullient, with the BSE Sensex staging a V-shaped recovery and rising over 91 per cent by end-March 2021 from the lows of March 2020, buoyed by strong corporate performance in Q2 and Q3 of 2020-21, the roll-out of a massive vaccine programme, fiscal and monetary stimulus in place and surges of capital inflows. The prospects for the Indian economy though impacted by the second wave, remain resilient backed by the prospects of another bumper rabi crop, the gathering momentum of activity in several sectors of the economy till March, especially housing, road construction and services activity in construction, freight transportation and information technology (IT). Meanwhile, the activation of the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, spectrum auctions and considerable easing of financial conditions are helping to shape the turnaround. On the other hand, large and medium-scale industry, mining and quarrying and several contact-intensive sectors remain subdued. II.1.6 Against this backdrop, component-wise analysis of aggregate demand is set out in the following sub-section. Developments in aggregate supply conditions in terms of the performance of agriculture and allied sectors, value added in the industrial sector, and performance of services are sketched out in sub-section 3. The sub-section 4 presents analysis of employment based on high frequency indicators. The concluding sub-section offers some policy perspectives. 2. Aggregate Demand II.1.7 The second advance estimate (SAE) that were released by the National Statistical Office (NSO) in February 2021 revealed that aggregate demand, measured by real GDP, contracted by 8.0 per cent in 2020-21 (Table II.1.1 and Appendix Table 1). This is the first contraction experienced since 1980-81 and the severest ever. In fact, the contraction was of the order of 15.9 per cent in the first half of 2020-21 under the full brunt of the lockdown imposed to curb the transmission of COVID-19. II.1.8 Progressive restoration in demand conditions was evident with a sharp rebound in seasonally adjusted annualised growth rate (SAAR) in Q2:2020-21, indicating a recovery in momentum. This was sustained in the next quarter as well, reflected in an uptick in the three-quarter moving average (MA-SAAR) of GDP in Q3:2020-21 (Chart II.1.1 and Appendix Table 2). | Table II.1.1: Real GDP Growth | | (Per cent) | | Component | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | | I. Total Consumption Expenditure | 7.8 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 5.9 | -7.1 | | Private | 8.1 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 5.5 | -9.0 | | Government | 6.1 | 11.9 | 6.3 | 7.9 | 2.9 | | II. Gross Capital Formation | 3.7 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 2.3 | -12.9 | | Fixed Investment | 8.5 | 7.8 | 9.9 | 5.4 | -12.4 | | Change in Stocks | -48.8 | 68.3 | 27.2 | -39.7 | -3.5 | | Valuables | -18.6 | 40.2 | -9.7 | -14.2 | -38.0 | | III. Net Exports | | | | | | | Exports | 5.0 | 4.6 | 12.3 | -3.3 | -8.1 | | Imports | 4.4 | 17.4 | 8.6 | -0.8 | -17.6 | | IV. GDP | 8.3 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 4.0 | -8.0 | | Source: NSO. |

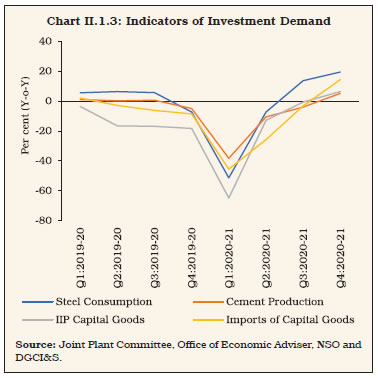

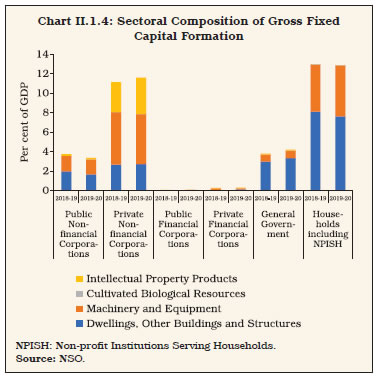

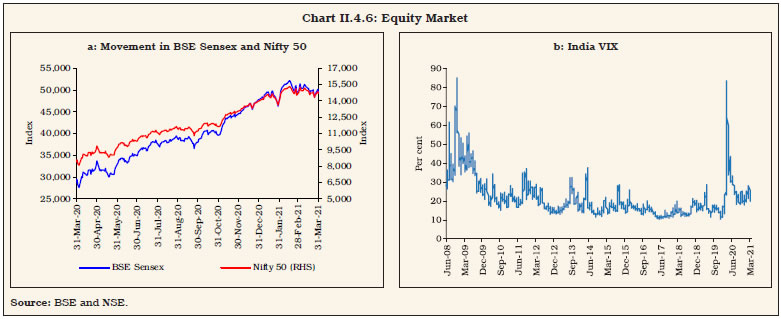

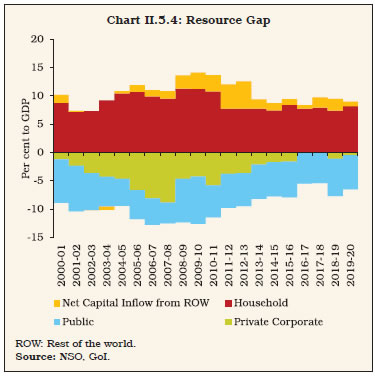

II.1.9 Underlying the vicissitudes in aggregate demand conditions in 2020-21 were compositional shifts among constituents. Private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) registered a contraction for the first time in the past four decades (Chart II.1.2). Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) continued to provide support to aggregate demand; however, its contribution waned in 2020-21 as stress mounted on government finances. Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) recorded a contraction, primarily due to prevailing uncertainty and the imposition of lockdown. There was a marked contraction in the external sector too; however, with imports declining sharper than exports, overall net exports made a positive contribution to aggregate demand. The contraction in GDP outpaced the retrenchment in gross value added (GVA) at basic prices on account of Food Corporation of India (FCI) food subsidies being reflected on the Union Budget. Consumption II.1.10 Private consumption - the mainstay of aggregate demand - was severely affected by the pandemic. Wilting from its innate resilience, PFCE contracted by 9.0 per cent in 2020-21, reflecting cliff effects of the impact of the stringent nation-wide lockdown and social distancing norms, heightened uncertainty as a result of transitory and permanent job losses, closures of small, micro and unincorporated businesses and wage resets. Discretionary consumption, particularly on transport, hotel and restaurants, recreation and culture, with a combined share of around 20 per cent in PFCE, remained much below pre-COVID-19 levels. Reverse migration of workers contributed to losses in disposable income, thereby negatively affecting domestic remittances and consumption. Although the deleterious ramifications were faced in both rural and urban areas, contraction in private consumption has been more pronounced in case of the latter. II.1.11 A sharp recovery in consumption has become evident from Q2. Passenger vehicle sales normalised since September 2020. In response to improving demand, production of consumer durables that remained sluggish during H1:2020-21, also witnessed a sharp revival in H2:2020-21. After a marked improvement in January, the March 2021 round of the Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey (CCS) showed a worsening consumer sentiment on the back of deteriorating sentiments on general economic situation, income and prices. The future expectations index (FEI) also indicated lower optimism for the year ahead. Going forward, the recovery of the economy from the COVID-19 will critically depend on the robust revival of private demand that may be led by the consumption in the short-run but will require acceleration of investment to sustain the recovery (Box II.1.1). II.1.12 Indicators of rural demand reveal a promising picture. The pandemic affected rural areas less than urban areas where population density is higher. Furthermore, agriculture and allied activities were generally exempted from the lockdown measures and exhibited resilience owing to a confluence of factors working in conjunction, viz., a bountiful monsoon, adequate soil moisture, replenished reservoir levels, improved labour availability during pandemic and favourable terms of trade for agricultural products. The acceleration in fertilizers production and tractor sales supported rural demand and brightened the outlook. After remaining in contraction for 19 consecutive months, motorcycle sales entered expansion territory in August 2020 and have since been robust. Investment and Saving II.1.13 The rate of gross domestic investment in the Indian economy, measured by the ratio of gross capital formation (GCF) to GDP at current prices, reduced to 32.2 per cent in 2019-20 from 32.7 per cent in the preceding year. Although data on GCF are not yet available for 2020-21, movements in its constituents suggest that the slowdown would continue. The ratio of real gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) to GDP decreased to 30.9 per cent in 2020-21 from 32.5 per cent in 2019-20, reflective of weak investment sentiment in the economy. GFCF registered a contraction of 12.4 per cent in 2020-21, in view of the prevailing uncertainty in the economy, waning business confidence and flagging entrepreneurial appetite for new investment. Fixed investment continues to be the Achilles’ heel of the economy and rekindling of animal spirits remains a top priority for policymakers. Box II.1.1

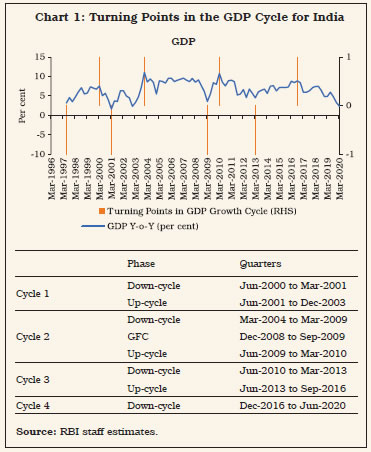

What Drives Recovery in Growth after a Crisis? For a self-sustaining GDP growth trajectory post-COVID-19, a durable revival in private consumption and investment demand together would be critical as they account for around 85 per cent of GDP. In view of the limited share of government consumption demand in GDP (at around 13 per cent in 2020-21), a rebound in private demand is essential to sustain the recovery. Typically, post-crisis recoveries have been led more by consumption than investment; however, investment-led recoveries can be more sustainable and can also lift consumption in parts by better job creation. In either case, private demand plays a pivotal role. In this context, the turning points in the growth cycle, determined by identifying the local maxima and minima - using the first and fourth quartiles of GDP growth, i.e., the lowest 25 per cent and the highest 25 per cent of the growth are examined. Additionally, a few censor rules are applied, such as eliminating back to back minima or maxima and ensuring that there is at least a one quarter gap between maxima and minima. These additional censor rules help to cleanly identify turning points in the GDP cycle (Chart 1).

| Table 1: Models of GDP Growth | | Dependent Variable | GDP Growth | | Consumption Growth | Investment Growth | | 1 | 2 | 3 | | Estimation Period | Q2:1998-99-Q1:2020-21 | Q2:1998-99-Q1:2020-21 | | Consumption | 0.63*** | | | Consumption*up-cycle | 0.17* | | | Consumption*down-cycle | 0.42*** | | | Investment | | 0.32*** | | Investment*up-cycle | | 0.14* | | Investment*down-cycle | | 0.26*** | ***: Significant at 1 per cent level.

*: Significant at 10 per cent level.

Source: RBI staff estimates. | A group of AR(1) models of GDP growth, augmented by current period (i) private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) and (ii) investment [gross fixed capital formation (GFCF)] is estimated (Table 1). The analysis uses the GDP cycle dating algorithm to create dummies that capture upcycles and downcycles. The findings suggest that an increase in consumption and investment during a downcycle boosts GDP growth more than during an upcycle. The analysis also suggests that an increase in investment leads to higher consumption4, suggesting that an investment-led recovery could boost both output and consumption. A mix of policies may be needed, as very low capacity utilisation rates may leave little incentive for the private sector to start a strong investment cycle. Therefore, there will be a need for an increase in public investment spending that can crowd in private investment, while private consumption needs to be supported through improvement in consumer credit. As a robustness check, high-frequency lead indicators of consumption and investment demand confirm that an increase in investment and consumption contribute more to GDP growth during a downcycle than in an upswing5. While an increase in investment leads to higher consumption demand through positive income and employment effects, an increase in consumption does not cause an increase in investment. Both results highlight the role of an investment-led recovery for sustaining the post COVID-19 rebound. Reference: Bhadury, S., S. Ghosh and P. Kumar (2020), ‘Nowcasting Indian GDP Growth using a Dynamic Factor Model’, Working Paper No.3, Reserve Bank of India. | II.1.14 Among the components of GFCF, construction activity remained subdued in H1:2020-21. Apart from being affected by the pandemic, construction was throttled by a stringent lockdown, reverse migration of workers from the urban construction sites, a large inventory overhang, coupled with stressed liquidity conditions in the early part of the pandemic. This was also reflected in its proximate coincident indicators – steel consumption and cement production (Chart II.1.3). Infusion of liquidity helped arrest the deterioration, and housing and construction activity rebounded in the latter half of the year with a gradual revival in sales, primarily due to favourable interest rates, steep discounts by developers to liquidate inventory, and reduction in stamp duty by a few states. There was a collapse in investment in machinery and equipment, reflective of muted investment by the private sector. Both its proximate coincident indicators – imports and production of capital goods - registered a contraction in every month of H1:2020-21.  II.1.15 At a disaggregated level, fixed investment in dwellings, other buildings and structures decreased by 0.3 percentage points to 15.5 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, mainly due to public non-financial corporations and the household sector, which offset the gains made by the general government sector through its thrust on infrastructure and affordable housing (Chart II.1.4). There has been a steady growth in fixed investment in machinery and equipment from 10.5 per cent of GDP in 2014-15 to 12.8 per cent in 2019-20, primarily led by the household sector. Investment in intellectual property products (IPP) - expenditure on research and development; mineral exploration; computer software; and other intellectual property products by private non-financial corporations picked up sharply in 2019-20.  II.1.16 As per the order books, inventories and capacity utilisation survey (OBICUS) of the Reserve Bank, seasonally adjusted capacity utilisation in manufacturing recovered from a sharp drop to 47.9 per cent in Q1:2020-21 to 66.6 per cent in Q3, though still below the long-term average of 73.8 per cent. The inventory-to-sales ratio fell sharply in Q2:2020-21 as sales exhibited an improvement with revival in economic activity while inventories remained close to their level in the preceding quarter. With an increase in both sales and inventories, inventory-to-sales ratio increased marginally in Q3:2020-21. II.1.17 The 93rd round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey (IOS) conducted during Q4:2020-21 points to further strengthening of production, order books and employment. While respondents’ sentiments on availability of finance through banks, internal accruals and overseas sources improved, they perceived higher cost pressures emanating from input purchases and salary outgoes. For the first three quarters of 2021-22, manufacturers are optimistic on improvement in production, capacity utilisation, employment conditions and the overall business situation. II.1.18 The rate of gross domestic saving picked up to 30.9 per cent of gross national disposable income (GNDI) in 2019-20 from 30.1 per cent a year ago. This increase was led by financial corporations - more pronounced in the public sphere - coupled with an uptick in financial saving of the household sector - the most important source of funds - by 0.7 percentage points to 7.8 per cent of GNDI in 2019-20, the highest in the past four years (Table II.1.2 and Appendix Table 3). Preliminary estimates show an upsurge in household financial savings to 21.0 per cent of GDP in Q1:2020-21 vis-à-vis 4.0 per cent in Q1:2019-20, owing to the COVID-19 led reduction in discretionary expenditure and the associated surge in precautionary saving despite stagnant/reduced income. The excess household financial savings, however, waned substantially and its rate dropped to 10.4 per cent of GDP in Q2:2020-21 as households switched from ‘essential only’ spending to discretionary spending with gradual reopening/unlocking of the economy. | Table II.1.2: Financial Saving of the Household Sector | | (Per cent of GNDI) | | Item | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | | A. Gross Financial Saving | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 11.1 | 11.0 | | of which: | | | | | | | | | | | 1. Currency | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 | -2.1 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 | | 2. Deposits | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 4.2 | | 3. Shares and Debentures | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | | 4. Claims on Government | -0.2 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | | 5. Insurance Funds | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.5 | | 6. Provident and Pension Funds | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | | B. Financial Liabilities | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.2 | | C. Net Financial Saving (A-B) | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 7.8 | GNDI: Gross National Disposable Income.

Note: Figures may not add up to the total due to rounding off.

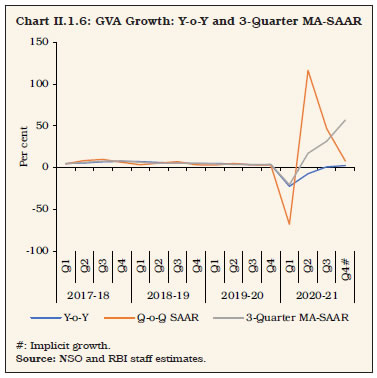

Source: NSO. | II.1.19 There has been a discernible narrowing in the saving-investment gap for the Indian economy since 2013-14, indicating that a larger part of investment funding requirement was being met through domestic resources (Chart II.1.5). The resource gap of non-financial corporations, both public and private, has registered a perceptible decline over the years, reflecting that their investment needs were increasingly being met through internal resources. The drawdown on saving by the general government sector remained at an elevated level and led to excessive draft on households’ financial surplus. 3. Aggregate Supply II.1.20 Aggregate supply, measured by gross value added (GVA) at basic prices, contracted by 6.5 per cent in 2020-21, after growing 4.1 per cent in the preceding year. Disentangling momentum from base effects, three-quarter moving average of seasonally adjusted annualised growth rate (MA-SAAR) of GVA exhibited an uptick in momentum in Q3:2020-21 with gradual easing of restrictions (Chart II.1.6). II.1.21 The deceleration in GVA growth was underpinned by a contraction in the industrial and the services sectors. While industrial GVA, driven by its largest constituent – manufacturing – moved out of contraction in Q3:2020-21, after having registered contraction in the preceding five quarters, the resilience of the agricultural sector provided a floor to the contraction in aggregate supply (Table II.1.3).

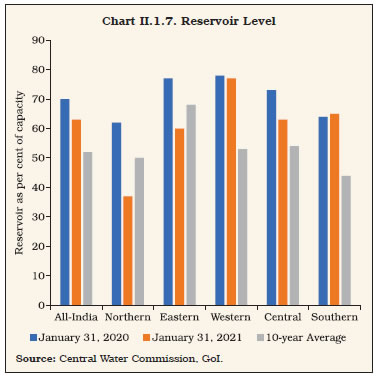

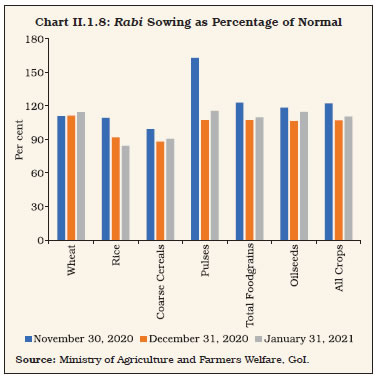

| Table II.1.3: Real GVA Growth | | (Per cent) | | Sector | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | | I. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 6.8 | 6.6 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 3.0 | | II. Industry | 8.4 | 6.1 | 5.0 | -2.0 | -7.4 | | i. Mining and Quarrying | 9.8 | -5.6 | 0.3 | -2.5 | -9.2 | | ii. Manufacturing | 7.9 | 7.5 | 5.3 | -2.4 | -8.4 | | iii. Electricity, Gas, Water Supply and Other Utility Services | 10.0 | 10.6 | 8.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | | III. Services | 8.1 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 6.4 | -8.4 | | i. Construction | 5.9 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 1.0 | -10.3 | | ii. Trade, Hotels, Transport, Communication and Services related to Broadcasting | 7.7 | 10.3 | 7.1 | 6.4 | -18.0 | | iii. Financial, Real Estate and Professional Services | 8.6 | 1.8 | 7.2 | 7.3 | -1.4 | | iv. Public Administration, Defence and Other Services | 9.3 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 8.3 | -4.1 | | IV. GVA at Basic Prices | 8.0 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 4.1 | -6.5 | | Source: NSO. | Agriculture and Allied Activities II.1.22 GVA by agriculture and allied activities registered a growth of 3.0 per cent in 2020-21, with record production in foodgrains. This was the only sector which remained in expansion zone in 2020-21, resulting in an increase in the share of agriculture in overall GVA by 1.5 percentage points to 16.3 per cent. II.1.23 The onset of the southwest monsoon (SWM) in 2020 was on time (June 1) and it progressed swiftly to cover the entire country by June 26, 2020, i.e., 12 days prior to its normal date. Notwithstanding a loss of momentum in the month of July due to less rains in north, east and central India, the rainfall revived subsequently and the cumulative SWM rainfall at the end of the monsoon season stood at 9 per cent above the long period average (LPA). As regards the spatial distribution, while 85 per cent of the subdivisions received normal and above normal rainfall, the cumulative rainfall in north-west India was 16 per cent below LPA. Aided by the good spatial and temporal coverage of the monsoon, the area sown was higher by 4.8 per cent year-on-year for kharif crops. II.1.24 The delayed withdrawal of SWM and the simultaneous start of north-east monsoon (NEM) [by October 28, 2020] created adequate soil moisture and reservoir levels. As on January 31, 2021, water storage stood at 63 per cent of the full reservoir level (FRL) capacity, up from the decadal average of 52 per cent (Chart II.1.7). This augured well for rabi sowing which got completed to the extent of 110 per cent of the five-year average (2013-14 to 2017-18) by January 31, 2021. The jump in rabi acreage this year is mainly driven by higher sowing under wheat, pulses and oilseeds (Chart II.1.8). Consequently, total foodgrain production in 2020-21 as per the second advance estimate (AE) is 3,033.4 lakh tonnes, 2.0 per cent higher than that in 2019-20 final estimate (FE) [Table II.1.4].

II.1.25 The production of horticulture crops during 2020-21 was a record at 3,266 lakh tonnes (1st AE), 1.8 per cent higher than the final estimate of 2019-20, surpassing the foodgrain production for the ninth consecutive year (Table II.1.5). The record production in horticulture crops was led by an increase in area under cultivation by 2.7 per cent in 2020-21 over 2019-20 even though productivity declined by 0.9 per cent. Onion cultivation witnessed the highest area expansion at 11.5 per cent. | Table II.1.4: Agricultural Production 2020-21 | | (Lakh tonnes) | | Crop | Season | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2020-21 | | 2nd AE | FE | Target | 2nd AE | Variation (Per cent) | | Over 2019-20 2nd AE | Over 2019-20 FE | Over Target | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | | Foodgrains | Kharif | 1,423.6 | 1,438.1 | 1,493.5 | 1,479.5 | 3.9 | 2.9 | -0.9 | | | Rabi | 1,496.0 | 1,536.9 | 1,516.5 | 1,554.0 | 3.9 | 1.1 | 2.5 | | | Total | 2,919.5 | 2,975.0 | 3,010.0 | 3,033.4 | 3.9 | 2.0 | 0.8 | | Rice | Kharif | 1,019.5 | 1,022.8 | 1,026.0 | 1,037.5 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.1 | | | Rabi | 155.3 | 165.9 | 170.0 | 165.7 | 6.7 | -0.1 | -2.5 | | | Total | 1,174.7 | 1,188.7 | 1,196.0 | 1,203.2 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | | Wheat | Rabi | 1,062.1 | 1,078.6 | 1,080.0 | 1,092.4 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | | Coarse Cereals | Kharif | 324.9 | 336.1 | 361.5 | 357.4 | 10.0 | 6.3 | -1.1 | | | Rabi | 127.5 | 141.3 | 116.5 | 136.3 | 6.9 | -3.5 | 17.0 | | | Total | 452.4 | 477.5 | 478.0 | 493.6 | 9.1 | 3.4 | 3.3 | | Pulses | Kharif | 79.2 | 79.2 | 106.0 | 84.6 | 6.8 | 6.8 | -20.2 | | | Rabi | 151.1 | 151.0 | 150.0 | 159.6 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 6.4 | | | Total | 230.2 | 230.3 | 256.0 | 244.2 | 6.1 | 6.0 | -4.6 | | Oilseeds | Kharif | 234.4 | 222.5 | 255.5 | 250.1 | 6.7 | 12.4 | -2.1 | | | Rabi | 107.5 | 109.7 | 114.5 | 123.0 | 14.4 | 12.1 | 7.4 | | | Total | 341.9 | 332.2 | 370.0 | 373.1 | 9.1 | 12.3 | 0.8 | | Sugarcane | Total | 3,538.5 | 3,705.0 | 3,900.0 | 3,976.6 | 12.4 | 7.3 | 2.0 | | Cotton # | Total | 348.9 | 360.7 | 360.0 | 365.4 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 | | Jute & Mesta ## | Total | 98.1 | 98.8 | 105.0 | 97.8 | -0.3 | -1.0 | -6.9 | #: Lakh bales of 170 kg each. ##: Lakh bales of 180 kg each. AE: Advance Estimate. FE: Final Estimate.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI. |

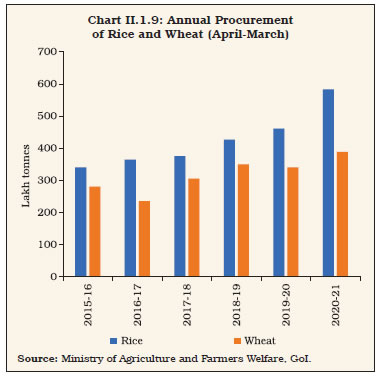

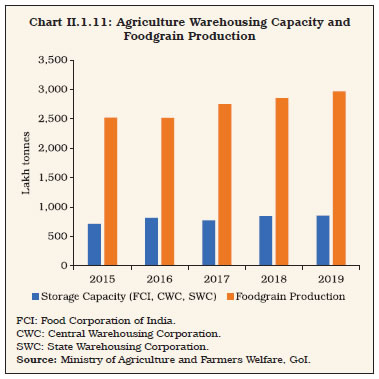

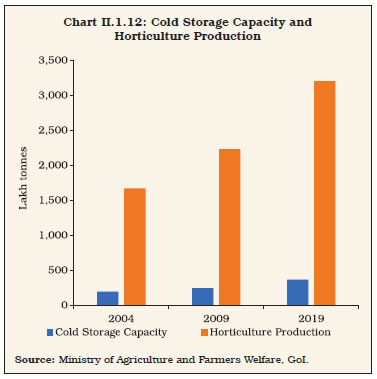

| Table II.1.5: Horticulture Production | | (Lakh tonnes) | | Crop | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | Variation (Per cent) | | Final Estimate (FE) | 1st AE | Final Estimate (FE) | 1st AE | 2019-20 FE over 2018-19 FE | 2020-21 1st AE over 2019-20 1st AE | 2020-21 1st AE over 2019-20 FE | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | | Total Fruits | 979.7 | 957.4 | 1,020.3 | 1,032.3 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 1.2 | | Banana | 304.6 | 296.5 | 326.0 | 337.3 | 7.0 | 13.8 | 3.5 | | Citrus | 134.0 | 131.8 | 145.7 | 142.4 | 8.7 | 8.0 | -2.2 | | Mango | 213.8 | 212.9 | 202.7 | 211.2 | -5.2 | -0.8 | 4.2 | | Total Vegetables | 1,831.7 | 1,880.1 | 1,889.1 | 1,936.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.5 | | Onion | 228.2 | 244.5 | 260.9 | 262.9 | 14.3 | 7.5 | 0.8 | | Potato | 501.9 | 519.5 | 485.6 | 531.1 | -3.2 | 2.2 | 9.4 | | Tomato | 190.1 | 193.3 | 211.7 | 201.5 | 11.4 | 4.2 | -4.8 | | Plantation Crops | 165.9 | 164.1 | 156.8 | 157.7 | -5.5 | -3.9 | 0.6 | | Total Spices | 95.0 | 93.7 | 103.0 | 102.4 | 8.4 | 9.3 | -0.5 | | Aromatics and Medicinal | 8.0 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 8.1 | -7.7 | -1.2 | 10.6 | | Total Flowers | 29.1 | 28.7 | 30.0 | 27.9 | 3.1 | -2.8 | -6.9 | | Total Horticulture Production | 3,110.5 | 3,133.5 | 3,207.7 | 3,265.8 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 1.8 | | Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI. | II.1.26 As in the previous three years, minimum support prices (MSPs) announced in 2020-21 for both rabi and kharif crops ensured a minimum return of 50 per cent over the cost of production. There has been an overall rise in the range of 2.1 to 12.7 per cent in MSPs announced during 2020-21 over the previous year. After record procurement of both rice and wheat in the kharif marketing season (KMS) 2019-20 (October 2019-September 2020) and rabi marketing season (RMS) 2020-21 (April-July 2020), respectively, the procurement of rice during 2020-21 is higher by 26 per cent over the previous year (Chart II.1.9). Despite a jump in offtake during March-November 2020 by 53 per cent over the corresponding period of the last year, the surge in foodstocks during 2020-21 has exacerbated the problem of plenty and brought to fore the inefficiencies in the food security system, with old stock not getting disposed due to inferior quality. As on March 31, 2021, the stocks of rice were 6.5 times the quarterly buffer norms and wheat at two times (Chart II.1.10). II.1.27 Concerted efforts were made so that harvesting and sowing cycles are not disrupted by the spread of COVID-19. Distribution of free foodgrains under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PM-GKAY) and AatmaNirbhar Bharat Scheme (ANBS) helped budget constrained consumers maintain their consumption levels at a critical time when safety nets needed to be ramped up to mitigate COVID-19 related hardships. Around 8.7 crore farmers were paid the first instalment of ₹2,000 under Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana in April 2020 itself. Additionally, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) wage was increased by ₹20 per day, implying supplementary income of around ₹2,000 per annum for around 13.6 crore rural families with an increased budgetary allocation of ₹40,000 crore for 2020-21. Under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyaan (PMGKRA), provision was made for additional employment to returnee migrant workers for 125 days in six states6 facing high reverse migration. The dates for ongoing conversion of agricultural gold loan and other agricultural accounts into Kisan Credit Card (KCC) accounts were extended. The benefit of 2 per cent interest subvention to banks and 3 per cent prompt repayment incentive for all farmers was extended up to August 31, 2020 for all crop loans up to ₹3 lakh given by banks, due between March 1 and August 31, 2020.  II.1.28 To facilitate transportation of perishable agricultural products, provisions were made for the deployment of railways at fast speed along with launch of Kisan Rath mobile app and All India Agri Transport Call Centre. Also, a fund with a corpus of ₹1 lakh crore has been proposed for development of agriculture infrastructure projects at farm-gate and aggregation points [such as cooperative societies and Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs)].  II.1.29 Apart from providing immediate succour, the government pressed ahead with far reaching structural reforms to address the built-in inefficiencies associated with public interventions in the farm sector. The Parliament passed three farm bills with the aim of giving a boost to rural India by increasing farmers’ income. They covered delisting of various agricultural commodities from the Essential Commodities Act (ECA) to develop seamless marketing and promote storage infrastructure in agriculture; ‘The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020’ to ensure barrier free trade of agriculture produce; and the ‘Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020’ to empower the farmers to engage with processors, aggregators, wholesalers, large retailers, and exporters in a fair and transparent manner. The Farm Acts are currently suspended by the Supreme Court and a four-member expert panel is examining them. II.1.30 Further reforms in the agriculture sector are needed. The current agriculture storage capacity in India in terms of warehouses and cold storages is substantially lower in relation to agriculture production (Charts II.1.11 and II.1.12). Moreover, many of the existing cold storage facilities are either sick or on the verge of getting closed due to lack of capital to upgrade plant and machinery as well as technology. The warehousing storage capacities available with government agencies are primarily used for keeping the central stock of foodgrain for the buffer stock, public distribution systems (PDS) are overstretched due to excessive foodstocks and also need modernisation. This suggests that there is a need for massive investments in storage and supply chain infrastructure in India.  II.1.31 A key role can be played by agricultural extension services to enhance farmers’ awareness and market intelligence to help them make informed decisions, policy stability to give right market signals and incentivise private investments, building bargaining power of farmers through initiatives like development and skilling of FPOs, building a reliable system of recording data particularly related to trade happening outside the Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) to ensure transparency and effective evaluation in future. II.1.32 The Union Budget 2021-22 has emphasised on infrastructure development in rural areas and the agriculture sector, promotion of agricultural diversification along with enhancing credit flow to allied sectors and improvement in supply chains for perishables through extension of ‘Operation Green’ to 22 perishable commodities. Enhancement in the allocation to the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) from ₹30,000 crore in 2019-20 to ₹40,000 crore in 2021-22 along with doubling of micro-irrigation fund will have a favourable impact on the rural economy and farm infrastructure. The Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess (AIDC) on several items (such as fuels, crude oilseeds, pulses and apple) has been imposed to generate funds for improving agriculture infrastructure. This increase in cost, however, has been offset by equivalent amounts of reduction in the basic custom duties to keep prices unaffected for farmers and consumers. On the other hand, custom duties on items such as cotton, raw silk, silk yarn has been increased to help farmers get better prices. The extension of agriculture infrastructure fund to APMCs and integration of additional 1,000 APMC mandis with the electronic national agriculture market (e-NAM) are expected to enhance marketing efficiency in the agriculture sector, thereby benefiting farmers through better access and higher transparency in mandis in years to come. The budget has also focused beyond the traditional activities to generate value addition for the farming community by enhancing credit flow to allied sectors and giving a boost to fisheries and seaweed cultivation.

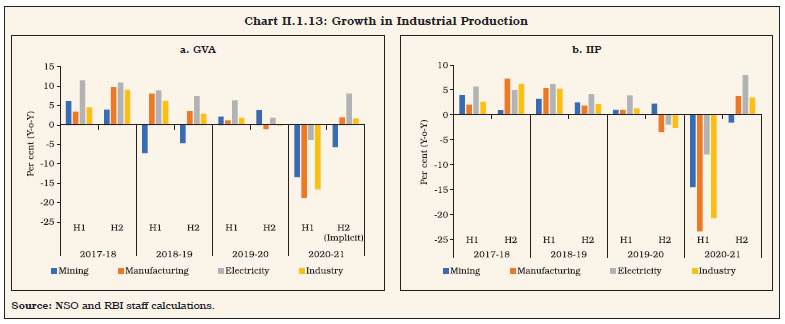

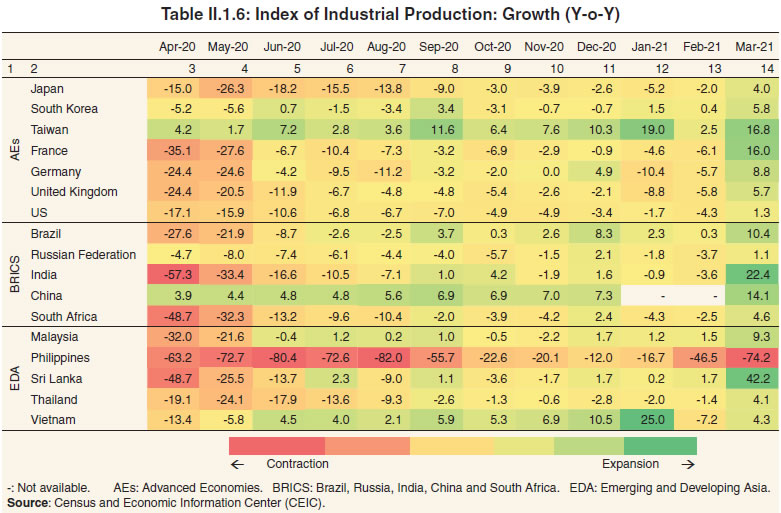

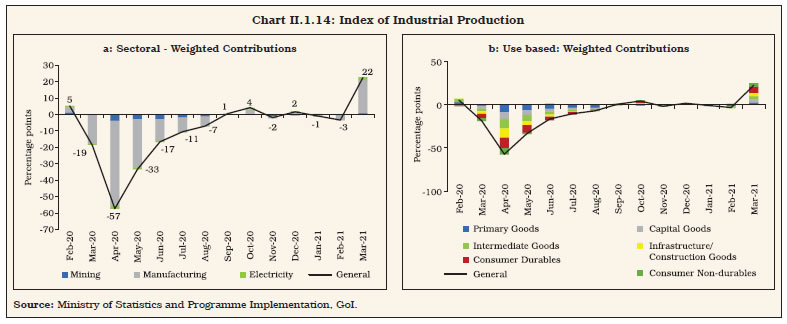

Industrial Sector II.1.33 GVA growth in industry contracted sharply on a y-o-y basis by 7.4 per cent in 2020-21. This is the fifth year of sequential deceleration, including two successive years of contraction in the industrial sector. During Q1:2020-21, industrial activity plummeted sharply, registering a contraction of 31.1 per cent. The turnaround in industrial activity since then has been volatile. IIP data show that the contraction was severe in case of consumer durables and capital goods, as consumers shunned discretionary expenditure while firms curbed investment. Cumulatively, the IIP declined by 8.6 per cent in 2020-21. At the sub-sectoral level, however, electricity, gas, water supply and other utility services recorded a growth of 1.8 per cent in GVA (Charts II.1.13a and II.1.13b) [Box II.1.2]. Box II.1.2

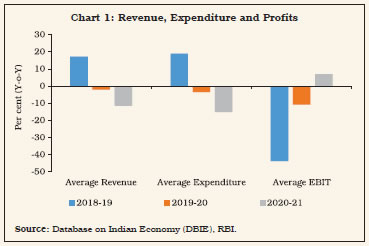

Impact of COVID-19 on Corporate Performance Following the announcement of a nation-wide lockdown on March 25, 2020 and restrictions on mobility that continued even after the gradual opening up of the economy, the corporate sector witnessed a sudden and sharp contraction in demand and also clogged supply chains due to stalled movement of goods, both for inputs used in production processes as well as final products meant for wholesale and retail sale. Survival of businesses in this environment of collapsing sales, vanishing cash flows and sticky operating expenses emerged as a key challenge. In Q1:2020-21, average revenue from sales contracted by 32 per cent for a sample of 2,536 listed firms. Firms resorted to aggressive cost cutting measures, enabling them to lower their total expenditure by 34 per cent. Profits nosedived, endangering their debt servicing capacity. Indian corporates, however, adjusted quickly to the altered business environment. As sales recovered in Q2:2020-21, cost cutting continued as the preferred path to regain efficiency and return to profitability. While revenue contraction moderated to 5.3 per cent, total expenditure (which includes costs) contracted by 12.5 per cent, enabling net operating profit to rise by 33.4 per cent in Q2. However, in Q3, revenue increased by 2.0 per cent and expenditure increased by 0.3 per cent that led to further increase in profits by 35.6 per cent. This in turn improved their capacity to service debt, as evident from the increase in interest coverage ratio (ICR) to 3.7 in Q2 and 4.5 in Q3 from 2.0 in Q1. As demand conditions in many segments normalised fully by the end of Q3:2020-21 to pre-COVID-19 levels, there was evidence of improvement in margins, on account of revenue recovery, cost saving and pass-through of increased costs to retail producer and retail prices. Therefore, profitability has improved further in Q3. In the three quarters of 2020-21 combined, revenues and expenditure declined by 11.6 per cent and 15.2 per cent, respectively, while operational profit (earnings before interest and taxes - EBIT) increased by 7 per cent year-on-year (Chart 1)7. The impact of COVID-19 has been varied for firms of different size/nature of operations. Evidence from both advanced and emerging economies show that smaller sized firms are relatively more vulnerable to extended periods of lockdown (Shen et al., 2020; OECD, 2020; Cowling et al., 2020). Larger firms may have found it easier to cut costs compared to smaller firms during the lockdown.  In India, although the interest coverage ratio (ICR) deteriorated for firms of all size categories in 2020-21, small firms appear to have been affected more by the lockdown in Q1:2020-21 (Chart 2)8. However, both small firms and large firms have improved their debt serviceability ratios in Q3 to levels which are higher than pre-pandemic period. Rise in profits and a sharp decline in borrowing costs contributed to the recovery in the interest coverage ratio. Industry-wise sectors which depend on discretionary spending by consumers were impacted more (such as hotels, recreation services, gems and jewellery), while sectors which were excluded from the lockdown (such as food and utilities) experienced relatively lower deterioration in ICR in Q1. References: 1. Cowling, M., R. Brown and A. Rocha (2020), ‘Did You Save Some Cash for a Rainy COVID-19 Day? The Crisis and SMEs’ International Small Business Journal, Vol. 38, No.7, Pages 593-604. 2. Shen, H., M. Fu, H. Pan, Z. Yu, and Y. Chen (2020), ‘The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Firm Performance’ Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Vol. 56, No.10, Pages 2213-2230. 3. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), [2020]: SME Policy Responses. | II.1.34 The decline in industrial activity was witnessed across countries (Table II.1.6). India witnessed the severest downturn and it was also one of the first to revive from contraction in September 2020, along with South Korea and Brazil, though growth remained volatile. II.1.35 The growth was supported by improvement in consumer durables and non-durables, especially consumer electronics and white goods, benefitting from pent-up demand (Charts II.1.14). II.1.36 The industrial recovery has also gradually become broad-based (Chart II.1.15). The manufacture of basic metals and motor vehicle segment, which were the largest negative contributors to manufacturing IIP during the lockdown period, saw revival since September 2020. Passenger vehicles and two wheelers, which were facing contraction even before the onset of COVID-19, registered a pronounced uptick since September 2020.

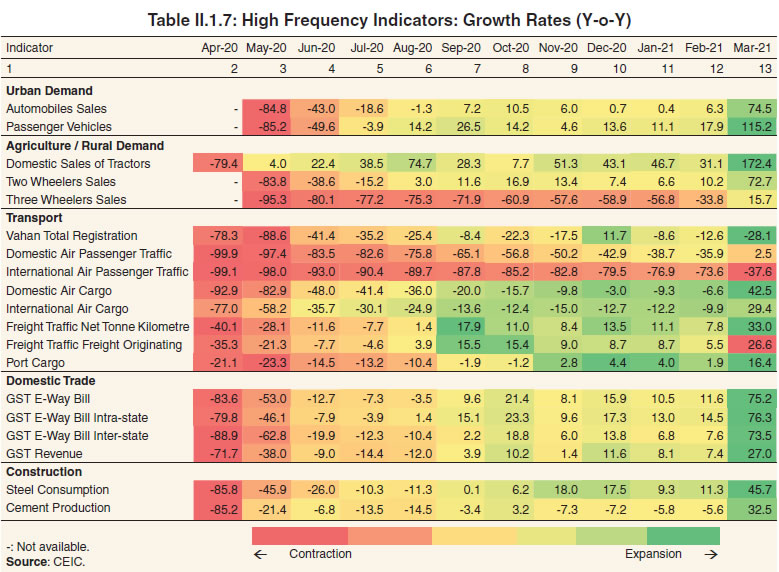

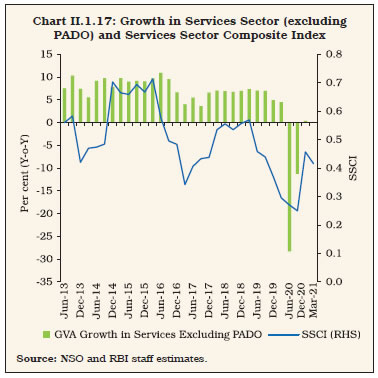

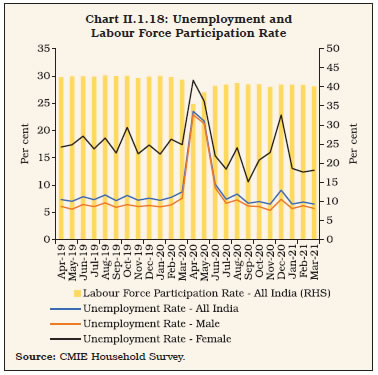

II.1.37 The mining sector also contracted sharply due to restrictions imposed on movement, lack of demand and labour supply shortages in H1:2020-21. An exception was the coal sector that showed relative resilience as it was exempted from the lockdown. Electricity generation also contracted in H1:2020-21, particularly in Q1, with lockdown restrictions halting manufacturing. With IIP manufacturing improving in the latter half, electricity demand also picked up. Hydro electricity and thermal generation contracted in 2020-21; however, thermal generation grew at a rate of 12.4 per cent in Q4:2020-21. II.1.38 The manufacturing capacity utilisation also remains at low levels (Chart II.1.16). Services Sector II.1.39 The contraction in the services sector in 2020-21 is unprecedented in independent India’s history. Even during the GFC, the services sector remained resilient. In 2020-21, however, construction suffered in the aftermath of the pandemic due to an inventory overhang in residential housing, coupled with stressed liquidity conditions which restricted new launches. The situation was exacerbated by imposed social distancing norms which led to construction activity in Q1:2020-21 getting reduced by half year-on-year. However, the revival of housing sector in H2:2020-21 has been a sharp ‘V’, with sales almost doubling in Q3:2020-21 sequentially, supported by favourable interest rates, adequate liquidity and steep discounts by developers to clear inventory, besides reduction in stamp duty by a few states. With new launches also registering a sharp rebound, the inventory overhang has dropped sharply. II.1.40 The contraction was severe in contact-intensive sectors as activities in hotels, restaurants, and passenger transport remained much below pre-COVID-19 levels. There has been a swift recovery in trading activities as evident in the collection of the goods and services tax (GST) and issuance of E-way bills. This has also imparted a boost to freight traffic. The performance of information technology (IT) companies has been better than their counterparts in the hospitality and the aviation segments. II.1.41 Sector-wise GVA trend estimates for the services show that realised growth in 2019-20 was below trend growth for trade, hotels, transport, communications and services relating to broadcasting and financial, real estate and professional services. In 2020-21, COVID-19 brought major services activities to a near halt and the sector contracted in a broad-based manner by 24.8 per cent in Q1:2020-21 and 10.9 per cent in Q2:2020-21, but in Q3:2020-21, services sector output returned broadly to its level a year ago. Domestic trading activities, railway freight traffic, port cargo, construction activities, and automobiles sales indicators for Q4:2020-21 suggested improvement in services sector. However, with the onslaught of second wave, many indicators showed a moderation though it was not to the extent of last year (Table II.1.7). II.1.42 The Reserve Bank’s services sector composite index (SSCI)9, which tracks activity in construction, trade, transport and financial services and is a coincident indicator of GVA growth in the services sector excluding public administration, defence and other services (PADO), witnessed a marginal decline in Q4:2020-21 after registering an uptick in the previous quarter (Chart II.1.17). 4. Employment II.1.43 As per the annual Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), the labour force participation rate (LFPR) was estimated at 37.5 per cent in 2018-19, which was an increase of 0.6 percentage points over 2017-18. In terms of gender divide, the annual PLFS report suggested that the LFPR for females continues to be lower at 18.6 per cent (rural: 19.7 per cent and urban: 16.1 per cent) in 2018-19, compared to the rate of 55.6 per cent for males (rural: 55.1 per cent and urban: 56.7 per cent). Some of the reasons cited for low female labour force participation include higher educational enrolment, higher household income and absence of suitable employment opportunities. More recent information on LFPR, as available from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) database, shows that it increased to 40.2 per cent in March 2021 from 35.6 per cent in April 2020 (Chart II.1.18).

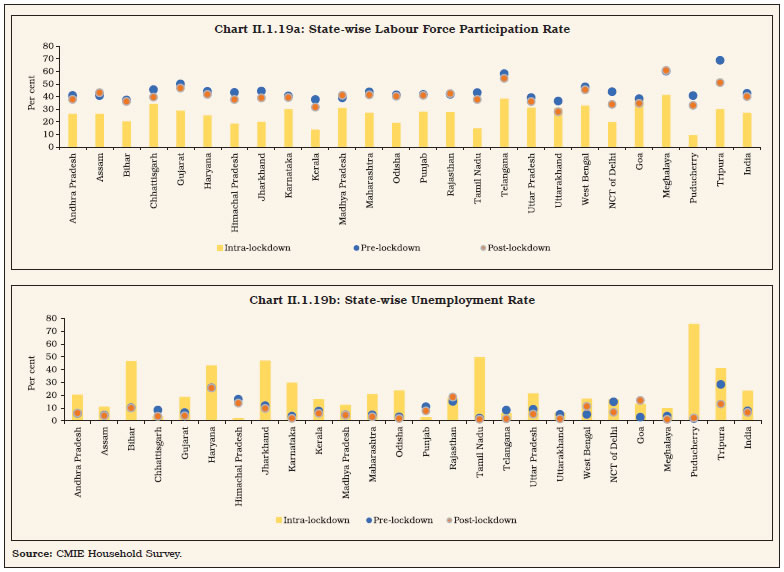

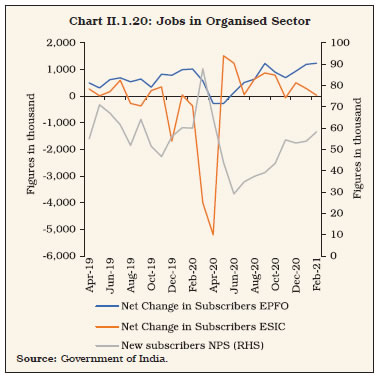

II.1.44 The majority of states recorded an improvement in employment conditions in the post-lockdown phase, supported by faster recovery in rural employment (Charts II.1.19a and II.1.19b). For the majority of states, LFPR has reached pre-lockdown period levels, with the exception of Delhi, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Tripura.  II.1.45 Updated data on organised sector employment measured by payroll data presents a mixed picture with regards to job creation in 2020-21 (Chart II.1.20). On a cumulative basis, the average of net subscribers added to Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) per month decreased marginally to 6.42 lakh in April-March 2021 from 6.55 lakh in the previous year. On the other hand, the average number of members who paid their contribution to Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) expanded by 0.64 lakh in April-February 2021 as compared with a contraction of 0.93 lakh in the corresponding period of the previous year. New subscribers to the National Pension Scheme (NPS) also decreased during the same period.

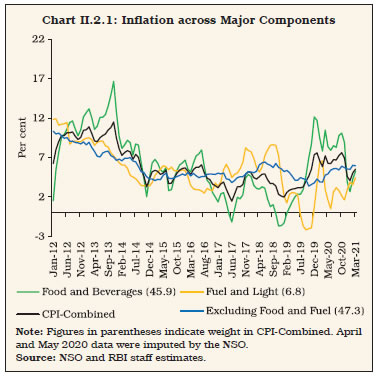

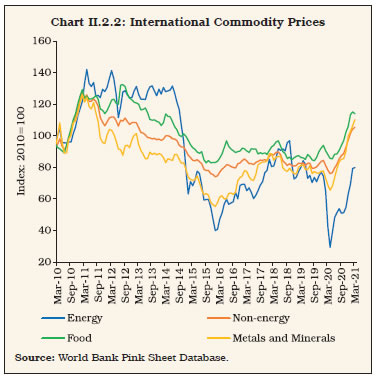

II.1.46 Several policy initiatives are being taken by the government to promote industrial production and generate employment opportunities. Apart from the measures taken under AatmaNirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, the Government of India introduced PLI scheme worth ₹1.45 lakh crore for 10 key sectors with the objective to attract investments, drive domestic manufacturing, create economies of scale and facilitate their integration with the global supply chain. 5. Conclusion II.1.47 Going forward, reform measures in various areas are likely to uplift India’s growth potential on a sustainable basis. To bring in transparency and credibility in land records and also for facilitating use of property as a financial asset, the government in October 2020 launched the Survey of Villages and Mapping with Improvised Technology in Village Areas (SVAMITVA) scheme. The scheme aims to reduce property litigations and transaction costs and improve the ease of doing business by bringing clarity in land ownership. In September 2020, three labour codes - Industrial Relations Code Bill, 2020, Code on Social Security Bill, 2020 and Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code Bill, 2020 were passed which would promote harmonious industrial relations, higher productivity and more employment generation. These measures would benefit workers of both formal and informal sectors and positively contribute to mitigate the distress of labour market in India. II.1.48 The launch of the proposed National Monetisation Pipeline will enhance the viability of potential brownfield infrastructure projects and is also likely to help real sectors significantly while freeing resources to finance further investment. The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) and the Power Grid Corporation of India Limited (PGCIL) have already sponsored one Infrastructure Investment Trust (InvIT) each, with investment of ₹5,000 crore and ₹7,000 crore, respectively. II.1.49 Moving forward, outturn predictability has turned a bit turbid. The growth prospects essentially depend on how fast India can arrest the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic. While the economy has not moderated to the extent during the first wave, the surrounding uncertainties can act as a deterrent in the immediate period. On the supply side, agriculture has proven its resilience, enduring the shock of the pandemic, thus providing support to rural demand and the economy at large. In case of services, recovery has been varied, with revival in construction, trade, freight transportation and information technology (IT) related activities. While performance of contact-intensive sectors is still sub-par, it is also improving. Going ahead, as the vaccination drive picks-up and cases of infections fall, a sharp turnaround in growth is likely, supported by strong favourable base effects. II.2 PRICE SITUATION II.2.1 The global inflation environment remained benign during 2020, with weak aggregate demand outweighing the impact of supply disruptions on commodity prices caused by the pandemic. Inflation in advanced economies dipped in 2020, while in emerging markets it remained sticky at around the previous year’s level. Producer prices softened through the year, but commodity prices rebounded since the second-half, raising concerns about a rise in global inflation on the back of cost push pressures. By March 2021, the World Bank energy price index was 2.7 times its April 2020 low, while ‘metals and minerals’ and agriculture commodity price indices were also up by 68.1 per cent and 26.6 per cent, respectively. Commodity prices have rallied on the back of the slush of global liquidity. Non-energy prices were up by 38.4 per cent, more than offsetting the pandemic-induced weakening of demand. II.2.2 While prices of food and medical supplies rose during the early phase of the lockdown, crude oil and metals prices became the drivers of reflation as rising discretionary consumer spending was unleashed when economies reopened and activity normalised. II.2.3 In India, headline inflation10, breached the upper tolerance band of the inflation target during June-November 2020 due to a sharp spike in food inflation and elevated core (excluding food and fuel) inflation on a combination of adverse developments, i.e., excess rains and supply disruptions; safe haven impelled increase in the prices of gold; and several rounds of hikes in pump prices of petrol and diesel on the back of firming crude oil prices and higher excise duties (Chart II.2.1)11. II.2.4 Although average inflation has remained high in 2020-21, its volatility measured by the standard deviation of the consumer price index (CPI) inflation was lower than a year ago (Table II.2.1). The intra-year distribution of inflation had a high negative skew, reflecting low food inflation prints during December 2020-February 2021, amidst persistently elevated inflation during the rest of the year. Furthermore, kurtosis turned less negative, suggesting few instances of large deviations from mean inflation, which was also reflected in the less wide gap between maximum and minimum inflation during the year.

| Table II.2.1: Headline Inflation – Key Summary Statistics | | (Per cent) | | | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21* | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | | Mean | 10.0 | 9.4 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 6.2 | | Standard Deviation | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | | Skewness | 0.2 | -0.2 | -0.1 | -0.9 | 0.2 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | -0.7 | | Kurtosis | -0.2 | -0.5 | -1.0 | -0.1 | -1.6 | -1.0 | -1.5 | -1.4 | -0.7 | | Median | 10.1 | 9.5 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 6.5 | | Maximum | 10.9 | 11.5 | 7.9 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 7.6 | 7.6 | | Minimum | 9.3 | 7.3 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.1 | *: Excluding the imputed data for April-May 2020, the mean works out to 6.1, standard deviation: 1.2, skewness: - 0.5, kurtosis: -1.1, median: 6.5, maximum: 7.6 and minimum: 4.1. Annual inflation is the average of the monthly inflation rates during the year and, therefore may vary from the annual inflation calculated from the average index for the year.

Note: Skewness and Kurtosis are unit-free.

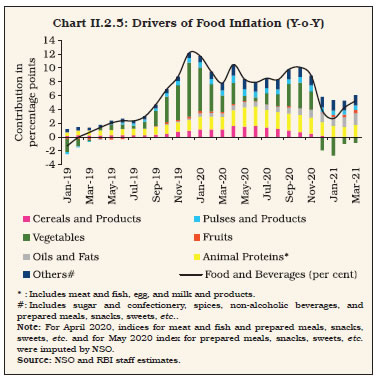

Source: NSO and RBI staff estimates. | II.2.5 Against this backdrop, sub-section 2 assesses developments in global commodity prices and inflation. Sub-section 3 discusses movements in headline inflation in India, followed by a detailed analysis of its major constituents in sub-section 4. Other indicators of prices and costs are analysed in sub-section 5, followed by concluding observations. 2. Global Inflation Developments II.2.6 International food prices firmed up from June 2020, primarily led by edible oils (palm oil; sunflower oil; and soybean oil) prices, driven by supply shortfalls as well as depreciation of the US dollar (Chart II.2.2). Prices of wheat (tightening supplies among major exporters and a Russian export tax as well as export quota), rice (tight Thai and Vietnamese availability), maize (weaker than expected harvest in the US and South America), meat (protein demand) and sugar also witnessed noteworthy increases. In the non-food category, metal prices recouped losses experienced during the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic and firmed up in consonance with the recovery in the global economy. Supply disruptions in Latin America and pick-up in industrial demand in China and other advanced economies added further upsides. Prices of precious metals, which surged in the beginning of the pandemic, remained elevated on safe-haven demand amidst heightened global uncertainties. By September 2020, however, these prices stabilised as demand for safe haven assets declined due to improving economic conditions. Global crude oil prices, which were on an easing trajectory during January-April 2020 due to the pandemic, picked up significantly from May 2020 on sharp oil supply cuts by the organisation of the petroleum exporting countries (OPEC) and their allies (OPEC plus) by 9.7 million barrels per day (bpd) [amounting to about 10 per cent of global oil supply] beginning May 2020 to be tapered gradually over a period of two years. Successful COVID-19 vaccine trials, and prospects of a faster than expected economic recovery lifted crude prices even further. Average Indian crude oil basket prices almost trebled, reaching US$ 65 per barrel in March 2021 from the low of US$ 20 per barrel in April 2020. Rising crude oil prices were supported by monetary policy easing by advanced economy central banks, supply restraints effected by OPEC plus and geopolitical events in March 2021 on account of attacks on Aramco oil facilities that sent oil prices soaring past US$ 70 per barrel. Demand for oil is expected to rise as global economic activity returns to pre-pandemic levels by 2022.  II.2.7 Reflecting these global commodity price developments, consumer price inflation in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) picked up after having declined sharply in the beginning of the pandemic, while inflation in advanced economies (AEs) remained below pre-pandemic levels as the effects of weak aggregate demand outweighed the impact of supply interruptions in these countries. 3. Inflation in India II.2.8 A nationwide lockdown was announced in India on March 24, 2020 to contain the spread of COVID-19. The initial lockdown was announced for 21 days effective from March 25, 2020 to April 14, 2020, but it was extended in phases till May 31, 2020, as the number of confirmed positive cases kept rising. Effective from June 1, 2020, announcements for relaxations in lockdown were made as part of “Unlock 1”. Further relaxations were announced in phases to resume services, bringing the economy back to normal as the number of new confirmed positive cases started to decline. As a result of the restrictions imposed during the lockdown, NSO could collect partial data largely through telephonic enquiries from the designated outlets and supplemented it by information collected through personal purchases of field staff of the NSO. Following the principles of adequacy12, indices for all sub-groups under food and beverages (barring meat and fish for April 2020, and prepared meals, snacks, sweets, etc. for April and May 2020), fuel and light, housing and health sub-group under the miscellaneous group were reported by the NSO during April-May 2020. II.2.9 In order to address the non-availability of data for several sub-groups during April-May 2020, the NSO undertook a separate exercise, based on the imputation methodology recommended in ‘Business Continuity Guidelines’ of the Inter-Secretariat Working Group on Price Statistics (ISWG-PS) in May 2020. Broadly, this approach advocated imputing the missing (due to non-availability of data) sub-group index with the index computed at the next higher level of aggregation. This imputation methodology mostly involved the items in the core or non-food non-fuel category, as transactional data for these items were not available during the lockdown. II.2.10 Headline inflation, which started picking up in H2:2019-20, remained elevated during 2020-21 and reached a multi-year peak of 7.6 per cent in October 2020 (highest in 77 months) [Chart II.2.3]. Supply disruptions during the nationwide lockdown, non-availability of labour at mandis, impediments to transportation, and excess rains during the kharif harvest period led to crop damages and pushed up food prices, especially those of vegetables. Subsequently, with the ebbing of these pressures and encouraging prospects for the rabi crop, food inflation started easing from November 2020 and reached 2.7 per cent in January 2021 from 10.1 per cent in October 2020, before increasing to 5.2 per cent in March 2021 largely due to adverse base effects. II.2.11 Fuel prices remained subdued during 2020-21 due to a fall in prices of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and non-PDS kerosene; however, LPG prices started increasing from December 2020 onwards. II.2.12 On the other hand, inflation excluding food and fuel, hardened during the year and reached a peak of 6.0 per cent in February 2021 from the historic low of 3.4 per cent in October 2019. This elevation was driven by near double-digit inflation in prices of transport and communication, personal care and effects, and pan, tobacco and intoxicants. II.2.13 For the year 2020-21, inflation picked up to average 6.2 per cent, 140 basis points higher than the previous year (Appendix Table 4). Reflecting the uptick in headline inflation from October 2019, households’ median inflation expectations hardened during 2020-21 by 159 basis points (bps) three months ahead and by 120 bps a year ahead as compared with March 2020 round readings. This upturn in expectations is also corroborated by more forward-looking assessments of professional forecasters. 4. Constituents of CPI Inflation II.2.14 The drivers of CPI headline inflation exhibited distinct shifts during 2020-21 with food group remaining the major contributor along with an increase in the contribution of transport and communication group (Chart II.2.4). Food price inflation moderated during May-June 2020 with the gradual relaxation of lockdown conditions and easing supply constraints, but it picked up again during August-October 2020 as excess rains led to crop damage. Food inflation again eased sharply during November 2020-January 2021 on seasonal ebbs in key prices and as a result, food inflation which had hovered over headline inflation during April-November 2020, trended below it from December 2020. Inflation excluding food and fuel generally remained elevated. Inflation in fuel prices remained subdued and below headline inflation throughout the year. Food II.2.15 Inflation in prices of food and beverages (weight: 45.9 per cent in CPI) crossed 6 per cent in October 2019 and remained elevated till November 2020, contributing 54.8 per cent to overall inflation in 2020-21. This was primarily driven by animal protein items and vegetables because of adverse supply shocks from lockdowns and crop damage caused by excess rains during the monsoon season (Chart II.2.5). Consumers resorted to panic buying and stocking durable food items like cereals and pulses at the beginning of the lockdown. Initial difficulties in transportation, despite food items being exempted from the lockdown related restrictions, and limited availability of labour at the mandis, led to sharp spike in food prices in April 2020.

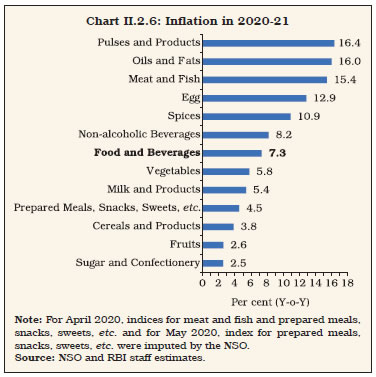

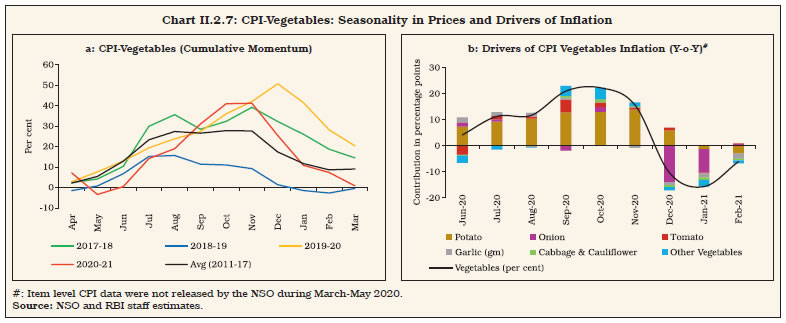

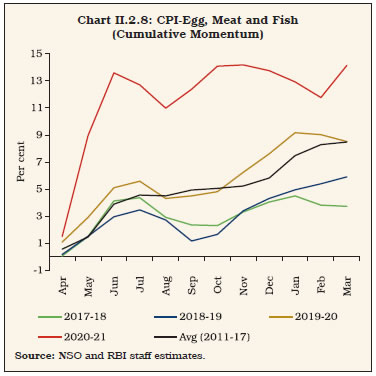

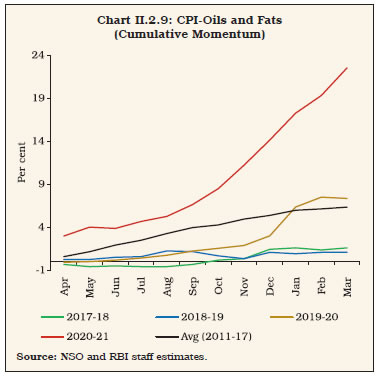

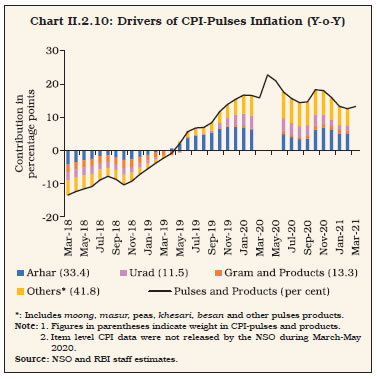

II.2.16 Within food and beverages group, price pressures remained high and broad-based over the ensuing months, with five out of the twelve sub-groups witnessing double digit inflation (pulses, oils and fats, meat and fish, eggs, and spices) [Chart II.2.6]. However, vegetables’ prices went into deflation from December 2020 as prices of onions, tomatoes and potatoes eased seasonally on the back of fresh crop arrivals, leading to a sharp softening in overall food inflation. Inflation increased again during February-March 2021 largely due to adverse base effects and sustained price pressures in oils and fats, pulses, prepared meals, snacks, sweets, etc., and non-alcoholic beverages. II.2.17 At the sub-group level, prices of vegetables (weight: 13 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) remained the key pressure point during April-November 2020. Excluding vegetables, food inflation would have averaged 96 bps lower during this period. Supply chain disruptions, excess rains and production shortfalls (in the case of potatoes) resulted in higher margins and similar build-up of momentum as in the previous year (Chart II.2.7a).  II.2.18 Onion prices underwent an uptick during September-November 2020, reflecting significant damages to kharif crops and late harvesting in major producing states due to excess rains. Higher exports during April-September 2020 by 35 per cent over the corresponding period of previous year also contributed to the ascent. As in the past, the government responded by banning the export of all varieties of onion on September 14, 2020 (lifted in January 2021); increasing imports of better quality (similar to the local variety); relaxing import norms [conditions for fumigation and additional declaration on the Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC) under the Plant Quarantine (PQ) Order, 2003] during October 21, 2020 to January 31, 2021; releasing buffer stocks; and imposing stock limits on wholesalers and retailers to curb market speculation and hoarding. These well-timed steps and fresh arrivals resulted in containing price pressures and onion prices moderated during December 2020-March 2021, barring February 2021 when prices increased due to lower arrivals. II.2.19 In the case of tomatoes, prices picked up during the lean season, i.e., June-July 2020, due to lower supplies on account of pre-monsoon rains related damages to crops and lower plantation than a year ago. Excess rains during the south-west monsoon again lifted prices in September 2020; thereafter tomato prices eased with fresh supplies entering the market. II.2.20 Inflation in potato prices surged from 2.3 per cent in November 2019 to 107.0 per cent in November 2020, which propelled vegetable group inflation to double digits during July-November 2020 (Chart II.2.7b). The two major potato producing states witnessed weather related disturbances - unseasonal rains in Uttar Pradesh in March 2020 and cyclone-related damage to the crop in West Bengal in May 2020 - leading to considerable supply disruptions and lower production [by 3.2 per cent as per final estimates (FE) 2019-20 over 2018-19 FE]. This was further aided by panic buying during the initial months of the lockdown, labour shortages at mandis and lower stock availability in cold storages. However, in October 2020, the government revised down the import duty on potato from 30 per cent to 10 per cent for a quota of 10 lakh tonnes until January 31, 2021 to improve the domestic availability along with relaxation of import norms similar to onions. Reflecting this and fresh arrivals, potato prices eased from December 2020. II.2.21 Inflation in prices of cereals and products (weight: 21 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) presented mixed dynamics - it remained above 6 per cent for the first four months, followed by moderation in the next eight months of 2020-21 even reaching into the deflation territory during February-March 2021, reflecting market distortions from a complex interplay of massive buffer stocks imparting downward pressure and higher procurement pushing up prices. At the item level, panic buying during lockdown, pick up in rice exports (81 per cent during April-February 2020-21), distribution of wheat and rice under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), record production of both rice and wheat [higher by 1.2 per cent for rice and 1.3 per cent for wheat as per 2nd Advance Estimates (AE) 2020-21 over 2019-20 (FE)], and moderate growth in minimum support prices (MSPs) [2.9 per cent and 2.6 per cent for rice and wheat, respectively] remained the major price drivers in this tangled development. II.2.22 Among protein-rich items such as eggs, meat and fish (weight: 8.8 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages), historically high build-up of price momentum was observed, leading to double digit inflation of 12.9 per cent and 15.4 per cent in the case of eggs and, meat and fish, respectively (Chart II.2.8). Initial fears caused by pandemic resulted in lower consumption demand for eggs and chicken during February-March 2020 which resulted in distress sale by poultry farmers to avoid making losses. As rumours cleared and demand picked up fiercely because of the perception that protein rich items are immunity boosting, supply could not match demand. Supply constraints caused by transport disruption and reverse migration also led to the price pick-up. Meat and fish prices, however, eased in December 2020 in contrast to the usual winter pick-up in prices, reflecting restoration of supplies in the poultry industry. The outbreak of bird flu in several states in January 2021 led to a fall in demand and further easing in prices of poultry items during January-February 2021. The price of chicken picked up sharply in March 2021 reflecting a recovery in demand amid short supply.  II.2.23 Oils and fats (weight: 7.8 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) went through a sharp price build-up, leading to a historically high inflation of 24.9 per cent in March 2021 (Chart II.2.9). Precautionary buying on account of the pandemic and rise in international prices of edible oils led to this adverse development. In order to contain the price escalation, import duty in the form of Basic Customs Duty (BCD) on crude palm oil (CPO) was revised down to 27.5 per cent from 37.5 per cent with effect from November 27, 2020, and revised further to 32.5 per cent [including the Agricultural Infrastructure Development Cess (AIDC)] in the Union Budget 2021-22. However, increasing global prices, increase in export levy on crude palm oil by Indonesia from December 2020 and imposition of 8 per cent export tax on crude palm oil by Malaysia from January 2021 kept prices high.  II.2.24 Prices of pulses (weight: 5.2 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) recorded a 45 month-high inflation of 22.8 per cent in April 2020 primarily led by tur (arhar) and urad (Chart II.2.10). Prices witnessed robust growth during the months of April-May and September-November 2020, reflecting stockpiling by consumers, lockdown and rain related supply disruption and a decline in kharif pulses production (lower by 2.1 per cent as per 2019-20 FE over 2018-19 FE and especially urad production by 43.6 per cent), higher exports and lower imports during April-February 2020-21 [27.2 per cent and (-)14.8 per cent, respectively]. Consequently, the government responded with an array of supply side measures, such as releasing 2 lakh tonnes of tur from the buffer stock through open market sales (OMS), extending the time limit for import of tur under an import quota of 4 lakh tonnes for 2020-21 as on December 31, 2020, expediting imports of urad under the already issued import quota of 1.5 lakh tonnes and extending the memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Mozambique for import of 2 lakh tonnes of tur for another five years. With pulses production rising by 6 per cent for 2020-21 (2nd AE) over 2019-20 (FE), tur, gram and masur prices eased during December 2020-February 2021.  II.2.25 Inflation in fruits (weight: 6.3 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) remained subdued during a large part of 2020-21, supported by robust production growth of 4.1 per cent in 2019-20 and 1.2 per cent in 2020-21 (as per 1st AE 2020-21 over 2019-20 FE). Inflation in sugar and confectionery (weight: 3.0 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) also remained subdued and averaged 2.5 per cent in 2020-21 reflecting higher domestic production. Fuel II.2.26 The contribution of the fuel group (weight of 6.8 per cent in CPI) to headline inflation increased to 2.9 per cent in 2020-21 from 1.9 per cent in the previous year. Fuel inflation eased from 6.6 per cent in March 2020 to 0.5 per cent in June 2020 largely due to easing in domestic LPG - which tracked international price movements - and kerosene prices (Chart II.2.11 and Chart II.2.12). Fuel inflation eased again during September-November 2020 due to favourable base effects and continued deflation in kerosene PDS prices. Inflation in firewood and chips and electricity remained moderate during the year, reflecting favourable base effects and possibly subdued demand during the lockdown period. Reflecting these developments, fuel inflation moderated to 1.6 per cent in November 2020 before rising to 4.4 per cent in March 2021 on the back of increase in LPG and kerosene prices.

Inflation Excluding Food and Fuel II.2.27 Inflation excluding food and fuel picked up over 2019-20 levels to an average of 5.5 per cent in 2020-21, with an intra-year peak of 6.0 per cent in February 2021 (Chart II.2.13). Inflation in this category continued to increase till October 2020 on the back of gold prices, hikes in taxes on liquor, and the hike in excise duties on petrol and diesel by the government in May 2020 (Chart II.2.14). It eased to 5.5 per cent by January 2021 due to favourable base effects, before picking up again to close the year at 5.9 per cent as favourable base effects waned and price pressures continued.

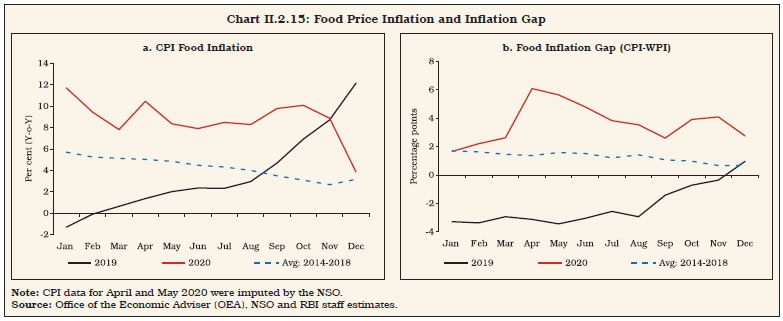

II.2.28 Among the major constituents of this group, inflation in miscellaneous category increased to 7.0 per cent in August 2020 and broadly remained elevated thereafter. II.2.29 Housing inflation moderated to 3.3 per cent in 2020-21 (4.5 per cent in 2019-20), reflecting the impact of favourable base effects and lower demand during the lockdown period. A historic low of 2.8 per cent was recorded in September 2020. Net of housing, inflation excluding food and fuel averaged 6.2 per cent in 2020-21, up from 3.9 per cent a year ago. II.2.30 Inflation in clothing and footwear remained moderate averaging 3.4 per cent in 2020-21, largely reflecting muted input costs and weak demand conditions. International prices of cotton, a major input into clothing production, as measured by the Cotton A Index, were affected by the outbreak of COVID-19 and registered a fall during February-April 2020, before recovering gradually thereafter. 5. Other Indicators of Inflation II.2.31 During 2020-21, sectoral CPI inflation, based on the consumer price index of industrial workers (CPI-IW), moderated to 5.1 per cent in May-June 2020 as the impact of the seventh central pay commission (CPC) on housing inflation dissipated and clothing inflation moderated. It dissipated and clothing inflation moderated. It increased during July-October 2020, reflecting increase in food prices. The Labour Bureau released CPI-IW with a new base (2016=100 from 2001=100) in October 2020 with data beginning from September 2020, reflecting the latest consumption pattern of industrial workers. It adopts a broadly similar classification of sub-groups/major groups as in CPI-C/CPI-Urban(U) (base: 2012=100) released by the NSO. Inflation based on the consumer price index for agricultural labourers (CPI-AL) and the consumer price index for rural labourers (CPI-RL), which do not have housing components, also eased to 6.3 per cent and 6.1 per cent in September 2020 from 8.8 per cent and 8.5 per cent in April 2020, respectively, due to favourable base effects, before increasing in October 2020 due to broad based price pressures especially in the case of food prices. All three measures witnessed easing in inflation in November 2020-January 2021 due to favourable base effects and easing in food prices before increasing again during February-March 2021 partly on the back of adverse base effects. II.2.32 Inflation, measured by the wholesale price index (WPI), remained subdued during 2020-21. It went into deflation during April-July 2020 and reached an intra-year low of (-) 3.4 per cent in May 2020 (lowest in 54 months) as prices of non-food primary articles, minerals, crude petroleum and natural gas, mineral oils and manufactured products declined due to a fall in global commodity prices and decrease in demand during the lockdown. Softer WPI inflation, however, did not pass-through to CPI inflation as mark-ups increased amidst social distancing and frozen markets. WPI inflation picked up during August 2020-March 2021, barring December 2020, and reached 7.4 per cent in March 2021 driven by price pressures mainly in fuel and power and manufactured products groups along with adverse base effects. On an annual average basis, WPI inflation softened to 1.3 per cent in 2020-21 from 1.7 per cent in 2019-20. The GDP deflator inflation, however, hardened to 4.6 per cent in 2020-21 from 3.6 per cent in 2019-20.  II.2.33 The divergence between WPI and CPI inflation reflected the behaviour of food inflation. CPI food inflation surged, following the imposition of a nation-wide lockdown even as food price inflation captured in the WPI eased, reflecting the role of supply chain disruptions and opportunistic pricing in raising mark-ups. The extent of retail price increase in the post-lockdown period was also much higher than the usual summer uptick in food prices (Chart II.2.15a). The gap between retail and wholesale price inflation – a proxy for retail margins or mark-ups also remained unusually high (Chart II.2.15b). Since the expected easing of supply disruptions got delayed even after the gradual opening up of the economy due to excess rain induced crop damages, mark-ups played a dominant role in the evolution of the inflation trajectory during 2020-21 (Box II.2.1). II.2.34 After the increases in MSPs during 2019-20 for kharif and rabi crops, there was another moderate hike in 2020-21. The extent of MSP increases varied across crops, ranging from 2.1 per cent in the case of moong and safflower to 12.7 per cent for nigerseed. MSPs of rice and wheat were increased by 2.9 per cent and 2.6 per cent, respectively. II.2.35 Wage growth for agricultural and non-agricultural labourers witnessed a major spike during the year, averaging 7.8 per cent and 7.2 per cent, respectively, during May-March 2020-21, reflecting the shortage of labourers during the lockdown period, and the hike in wages under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) 2005 by ₹20 effective from April 1, 2020 announced by the central government. However, the growth rates moderated to 6.8 per cent and 5.6 per cent, respectively, in November 2020 from their peaks of 10.5 per cent and 9.9 per cent in June 2020 and July 2020, respectively, before increasing marginally during December 2020-March 2021. Box II.2.1

Post-COVID-19 Surge in Mark-ups and Food Inflation Surprise The Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) collects, monitors and publishes daily prices of 22 essential food items for 135 centres spread across the country. The DCA data show an increase in retail margins for the 22 food items during the lockdown period (Chart 1a) which varied across centres depending to some extent on the degree of mobility (Chart 1b). An empirical exercise to understand the causal impact of lockdown-induced supply disruptions on price margins of 22 food items across 80 centres13 using a panel regression model14 based on the difference in difference (DID) strategy (Varshney, Roy and Meenakshi, 2020) is evaluated for two sub-samples - centres which experienced comparatively stricter lockdowns vis-à-vis others. Variation in lockdown intensity across centres is measured using Google mobility indices. A high mobility centre (low intensity of lockdown) is defined as the one which witnessed a lower than median fall in the mobility index during the lockdown period. The results show that the interaction term corresponding to the lockdown phase is positive and significant, indicating that the lockdown led to an increase in margins (Table 1). The results also indicate that the increase in margins predominantly originated from low mobility (high lockdown intensity) centres. | Table 1: Price Margin Across Centres | | | All Centres | High Intensity Lockdown Centres | Low Intensity Lockdown Centres | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | | 2020=1 × March 25-May 31=1 | 0.441*** | 0.602*** | 0.136 | | | (0.0914) | (0.116) | (0.142) | | 2020=1 × June-Nov=1 | 0.312** | 0.372* | 0.228 | | | (0.144) | (0.191) | (0.185) | | Adjusted R2 | 0.779 | 0.776 | 0.800 | | Observations | 834133 | 573750 | 260383 | Note: Centre × Commodity FE, State × Month FE, State × Year FE, Commodity × Month FE, and Commodity × Year FE are included in all the above specifications. Standard errors are clustered at the commodity-centre level. Standard errors in parentheses.

***: Significant at 1 per cent level. **: Significant at 5 per cent level.

*: Significant at 10 per cent level.

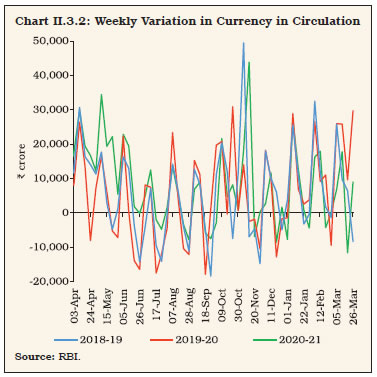

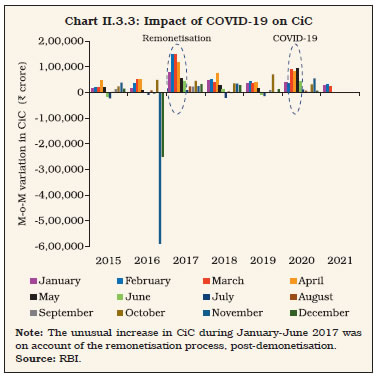

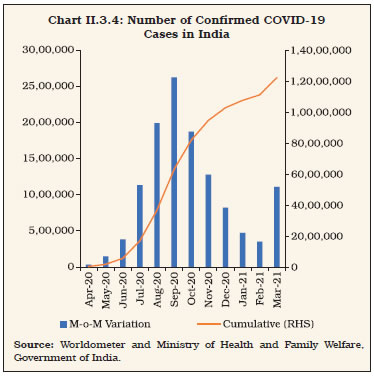

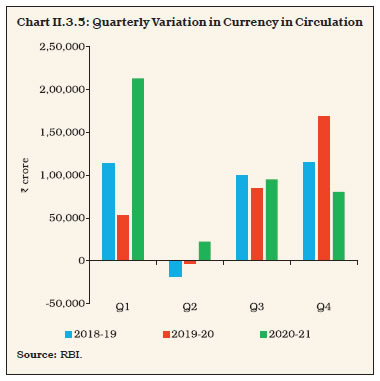

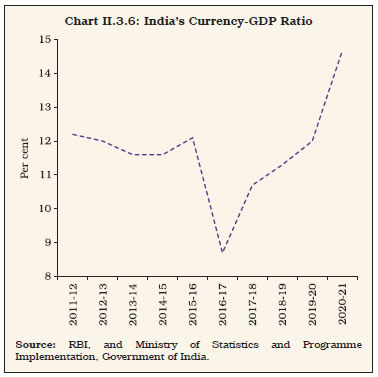

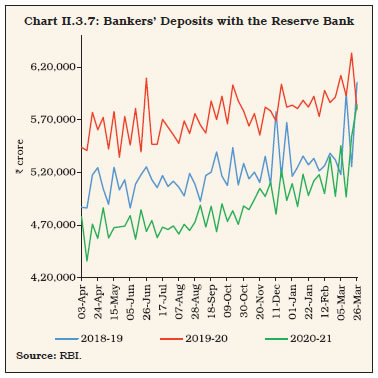

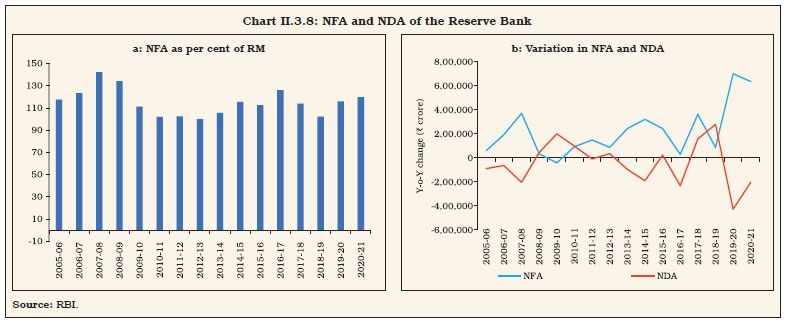

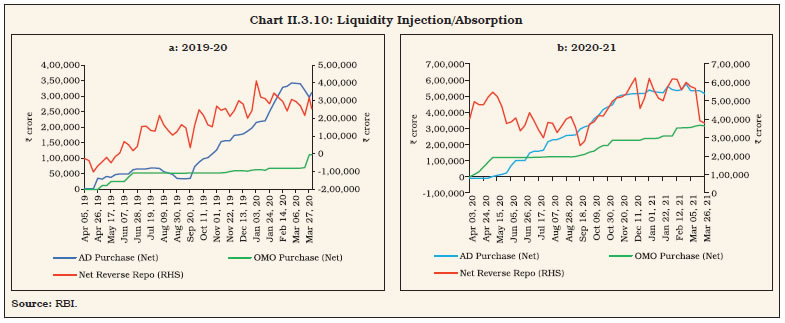

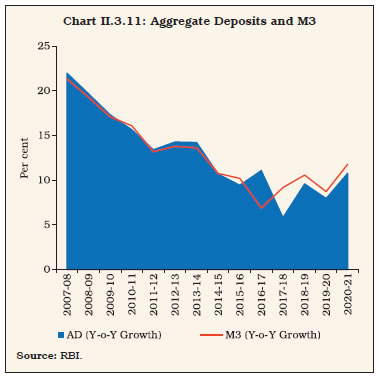

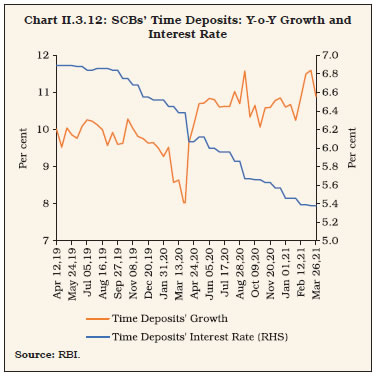

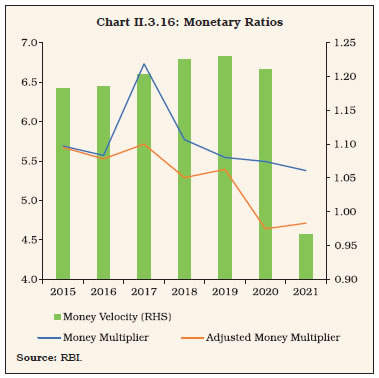

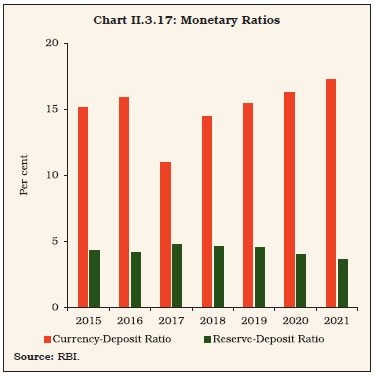

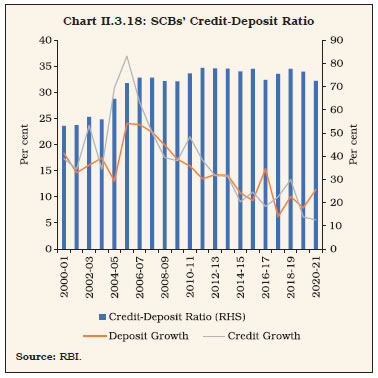

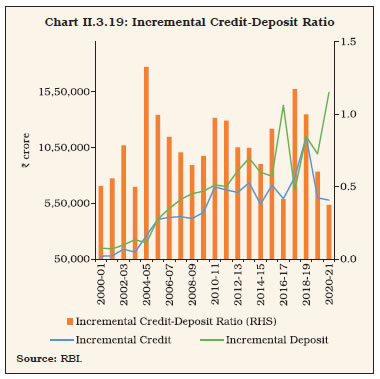

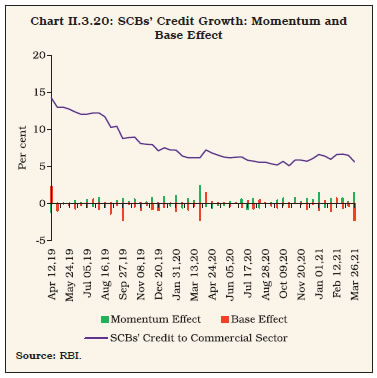

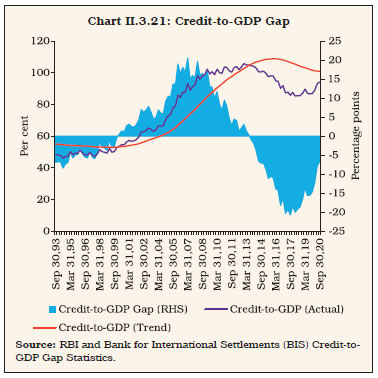

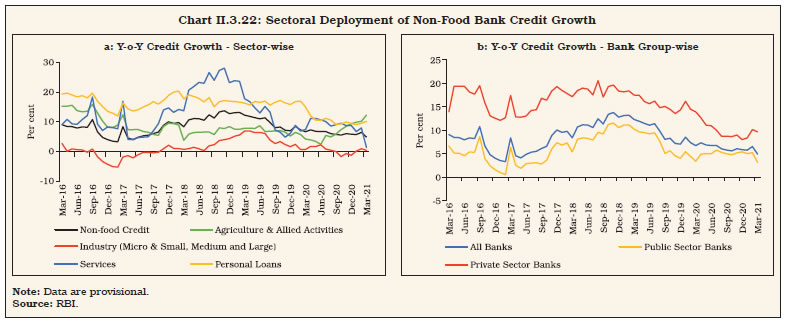

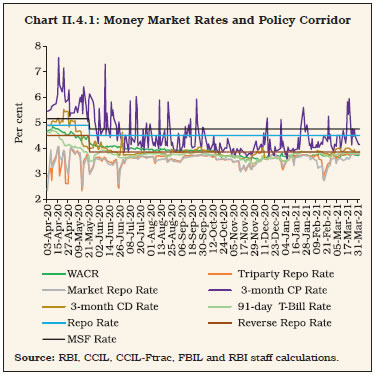

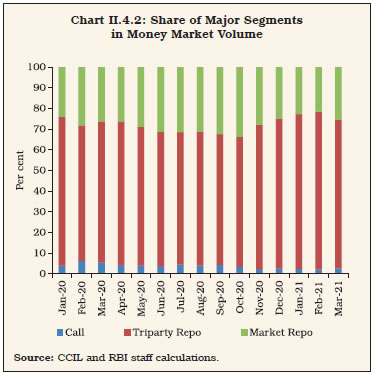

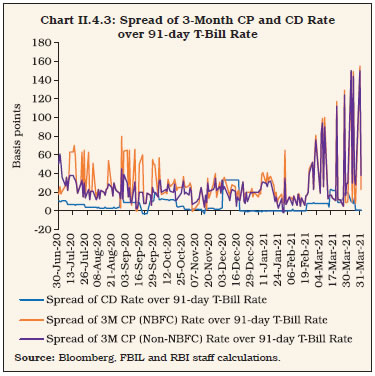

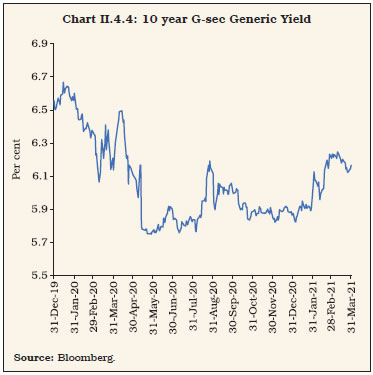

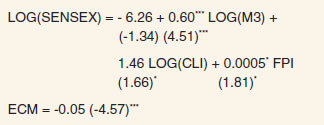

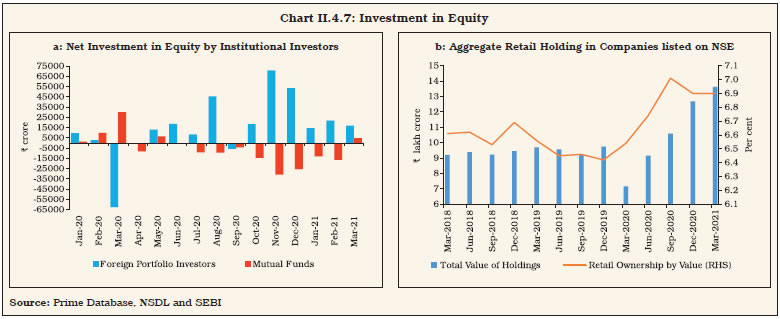

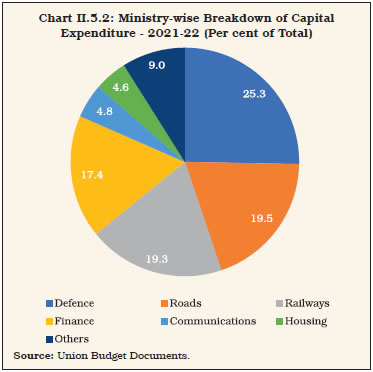

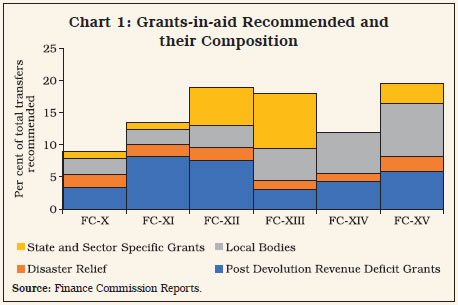

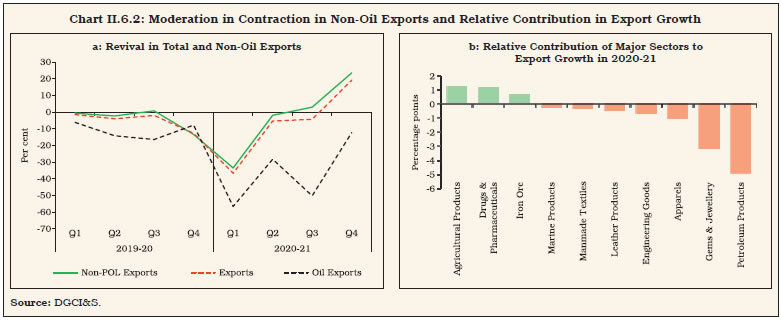

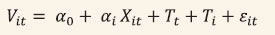

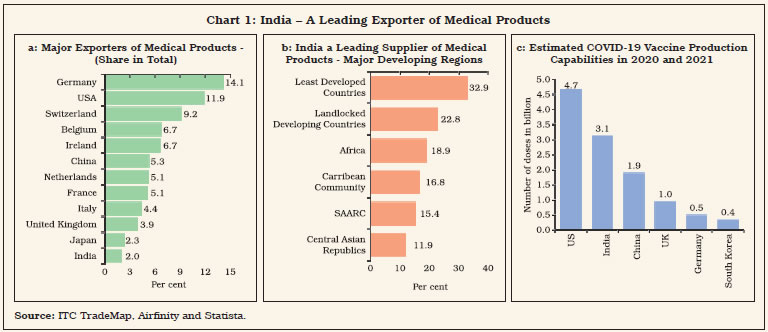

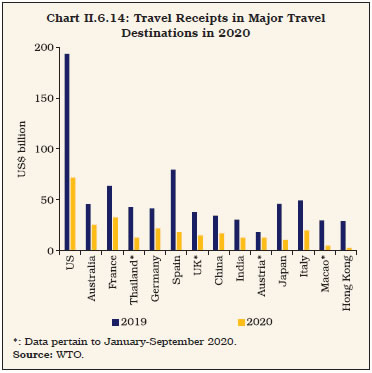

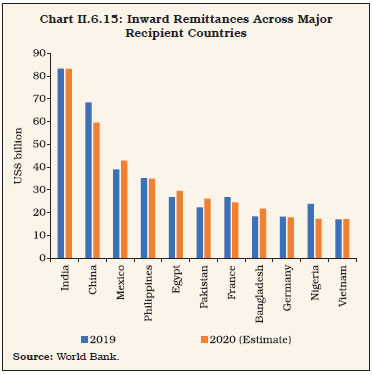

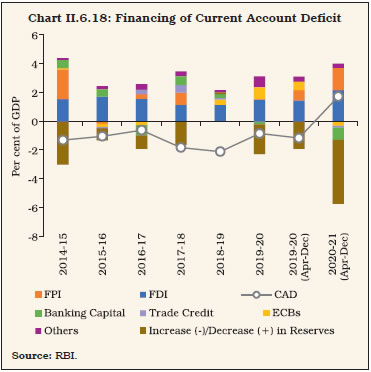

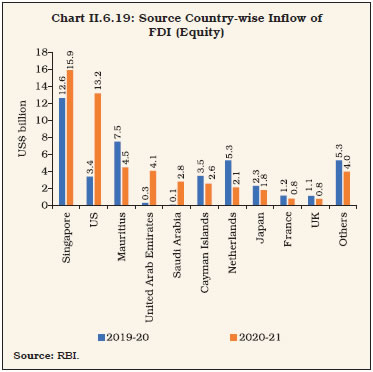

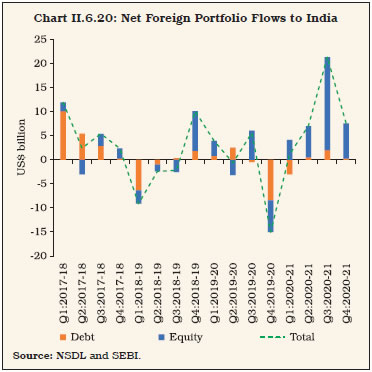

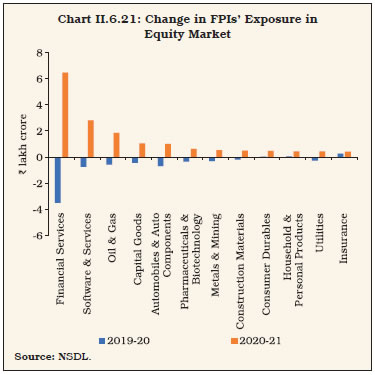

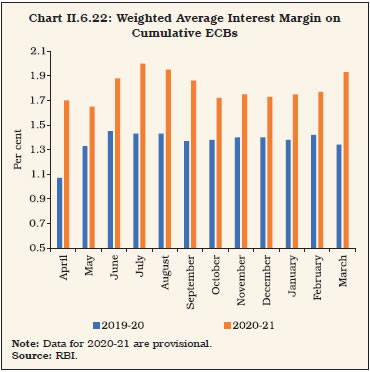

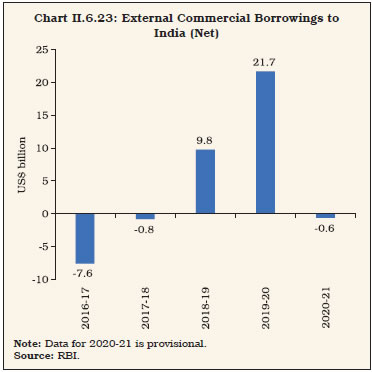

Source: RBI staff estimates. |