At the outset, I thank National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) for inviting me to this esteemed gathering of experts in the field of rural finance. I am happy that NABARD has organised this National Seminar to mark the completion of 32 years of its existence. Built upon the legacy of Agricultural Credit Department of the Reserve Bank of India and the Agriculture Refinance Development Corporation (ARDC), NABARD today has carved for itself a special place, especially in the area of rural financing and development. Many of the innovative financial products and services developed and mainstreamed over the last three decades for the rural economy can be either directly attributed to the NABARD or have been positively influenced by the NABARD. I am also happy that topical issues in the field of rural finance were deliberated upon today as part of this seminar. I am sure that the seminar has provided a lot of useful insights in the field of rural finance for all of us and these inputs will help us in informed policy making.

Challenges in developing an inclusive rural financial system

2. Providing financial services in rural areas is a challenge as agriculture and other rural economic activities have unique characteristics of dependence on natural resources, long production cycles and vulnerability to multiple risks (all of us remember the old adage “Indian agriculture is a gamble in monsoon”). Further, the sub-division of land and small ticket size of rural non-farm activities require the provision of small sized loans in large numbers often raising the operational costs for banks. Moreover, with the widening of the ambit of non-agricultural activities, the need for non-agricultural rural finance too has gone up considerably. While poorer groups might need basic savings services and micro-credit to cover production costs and emergency expenses, farmers and farmers’ organisations require larger amounts of credit to finance production, inputs, processing and marketing besides risk mitigation products, for example, insurance for loss of life and assets. The new rural finance paradigm needs to be based on the premise that ‘rural people are bankable’ and rural clientele is not limited only to the farmers & uneducated but also includes a generation which can use & adopt technology. It, in turn, advocates a demand-driven design and efficient provision of multiple financial products and services through an inclusive financial sector comprising sustainable institutions serving a diverse rural clientele.

3. Thus, developing an inclusive yet sustainable rural financial system is extremely challenging and involves comprehensive understanding of host of complementary issues, which I would like to subsume under a broad 7Ps’ Framework:

-

Product strategy: For catering to the varied needs of small ticket size transactions, whether a bouquet of diversified products and services can be developed without compromising on the flexibility, continuous availability and convenience of the products? Which types of financial products have the greatest impact on reducing poverty and lifting growth rates in deprived districts and regions?

-

Processes: What kinds of business processes can help banks to reach underserved segments and provide hassle-free near doorstep service to the customers without jeopardising financial viability? How do we design an efficient hub & spoke model to overcome the hurdles in the agent led branchless banking?

-

Partnerships: What are the constraints faced by the underserved and/or excluded segments in accessing financial services from different types of service providers? Are the bank - non-bank partnerships, such as, Business Correspondents, SHGs, MFIs, etc. working efficiently in easing the accessibility and availability of financial services?

-

Protection: What measures and mechanisms are needed to protect both the providers and the receivers of rural finance from abuse and misuse of such services? Whether enough risks mitigants are there for the borrowers given the higher vulnerability in the sector? Are lenders protected against ebb & flow of uncertainty in credit culture?

-

Profitability: Whether the business strategies and delivery models are geared to provide affordable and acceptable services to the rural clientele while ensuring that rural finance service providers function profitably on a sustained basis? How do we tap into the customer willingness to pay through an appropriate pricing model?

-

Productivity: How do we increase the productivity of financial services provided in the rural areas? What are the strategies needed to synergize other resources with finance (say, under a “credit plus” approach) to ensure more productive and optimal use of financial services?

-

People: Are the frontline staff of the financial service providers well-equipped to meet the needs of driving the process of financial inclusion in terms of knowledge, skill and attitude? Do these people have the capacity, comprehension and commitment to identify potential customers and offer them timely advice and comprehensive services?

Many of these are the age-old questions which unfortunately remain pertinent even today and pose a significant challenge to the policy-makers and regulators. Having spoken about the challenges, let me outline some of the developments that have taken place in recent times in rural finance space with specific reference to the three sub-themes of this seminar and highlight some of the critical issues related to these sub-themes.

Capital formation in agriculture and rural infrastructure

Trends in capital formation in agriculture and agricultural credit

4. In any discourse on rural development, agriculture is put on the top of development agenda and for valid reasons too. Around 50 per cent of population depends on agriculture for its livelihood. A positive relationship has been found between agriculture growth and poverty reduction. Also, improved growth in agriculture tends to trigger rural non-farm activities which can bring down rural unemployment. Further, there are various forward and backward linkages of agricultural sector with other sectors of the economy. In the past couple of decades, a rapid decline in the share of agriculture in GDP, however, has been witnessed without a commensurate decline in labour force dependent on agriculture. Another sign of concern has been a deceleration in the growth of gross capital formation (GCF) in agriculture in real terms in the recent past. Moreover, GCF in agriculture has generally grown at a rate slower than the rate of growth in overall GCF over the last decade, except for a spurt between 2007-08 and 2008-09 (Chart 1).

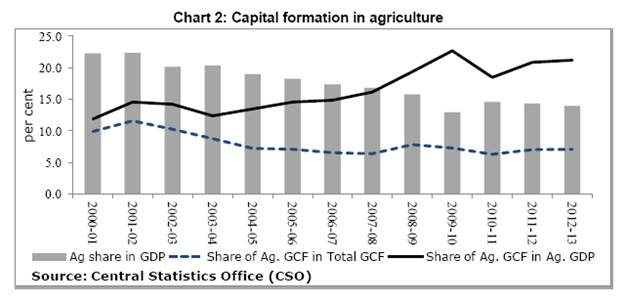

5. The elementary growth theory tells us that the growth of a sector depends upon the investments made in that sector, its capital-output ratio, and the efficiency of capital in that sector. During much of the period from 1980-81 onwards till 2007-08, the investment rate in agriculture (GCF as per cent of GDP in agriculture) was always below 16 per cent. It is only in recent years that this rate has crossed the 16 per cent mark and we have seen some positive results on the agricultural growth front. In fact, the rate of investment was 22.7 per cent in 2009-10. It has, however, shown fluctuations thereafter (Chart 2).

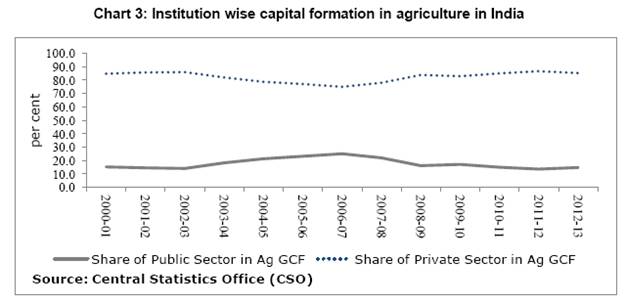

6. It is interesting to note that in the early 1980s, the share of public and private investment in agriculture was almost equal, but subsequently the share of public investment fell drastically. There was an attempt in the early 1990s to increase the share of public investment, but the impetus did not last long. There was marginal improvement in this share during 2003-07 but it declined in the subsequent period. In 2012-13, the share of public sector in agriculture amounted to only about 15 per cent of total GCF (at 2004-05 prices) (Chart 3). So, private sector, the farming community itself, was a major driver of growth in the agricultural sector. The Union Budget 2014-15 has rightly recognised the need to revive public investment and has enhanced the sum allocated towards agriculture investment and warehousing.

7. Let us now turn to some of the trends in agricultural credit. Tenure-wise pattern of agricultural credit suggests that the share of long-term credit in total agricultural credit experienced a secular decline, reaching 37.8 per cent in 2011-12 from 74.3 per cent in 1990-91 (Chart 4). Focus on crop loans with availability of interest subvention only partially explains this phenomenon. This is a disquieting trend. It suggests a possible neglect of capital formation in agriculture. Given that private sector is the major driver of the capital formation and that rate of investment in agriculture, which presently hovers around 20 per cent need to be sustained and in fact raised further, there is a need to give immediate attention to long-term agricultural credit. The issue of sharp decline in project based lendings spearheaded earlier by the NABARD also needs urgent attention for improving share of long-term credit. The key thrust areas of such schematic lendings will have to be in areas like production and marketing of protein foods, vegetables & fruits, organic farming, supply chain management and farm mechanization.

Select trends in Rural Infrastructure

8. While capital formation in agriculture directly reflects the investment in agriculture, rural infrastructure, a much broader concept, refers to all possible physical and social infrastructure that create a conducive environment for growth in rural areas. Several studies confirm the positive link between rural infrastructure and improved livelihoods and productivity and reduced poverty. While almost all rural infrastructure sectors are under State Governments, Central Government spending has also been significant in recent years. Overall, the outlay on rural infrastructure has increased over the years with around ` 3 trillion spent under various heads for rural infrastructure by the Central Government during the year 2000-12. Out of this, largest sum went to development of rural roads followed by rural drinking water and sanitation and rural housing. Irrigation received around 16 per cent of the total rural infrastructure during this period (Table 1).

Table 1: Central Government spending on rural infrastructure (2000-12) |

(at 2006-07 prices) |

(` billion) |

Items |

Total expenditure |

Share (%) |

Rural roads |

905.17 |

29.8 |

Rural drinking water and sanitation |

623.42 |

20.5 |

Rural housing |

485.11 |

16.0 |

Irrigation |

481.84 |

15.9 |

Rural electrification |

241.00 |

7.9 |

Telecommunication |

138.51 |

4.6 |

Watershed |

105.57 |

3.5 |

Integrated Action Plan (IAP) |

36.54 |

1.2 |

Storage |

19.72 |

0.6 |

PURA |

2.06 |

0.1 |

Actual expenditure on rural infrastructure |

3038.94 |

100 |

{Note: All figures include both Plan and non-Plan expenditure; Storage data (for constant 2006-07 prices) consists of expenditure on construction of rural godown, investment in the Food Corporation of India and the Central Warehousing Corporation. Figures may not add up exactly to 100 due to rounding off.}

(Source: India Rural Development Report, 2012-13) |

9. Looking at the state of physical infrastructure in rural areas, we see that it has certainly improved but it still leaves a lot to be desired. It is estimated that rural roads have connected around 69 per cent of habitations that were planned to be covered by 2013, but the smaller and more remote ones are yet to be connected. Further, in 2011 almost all villages were connected to the grid, but as much as 45 per cent of rural households still lacked electricity connections2. Electricity supply is often unreliable and water supply is unavailable or polluted.

10. Irrigation is one of the most important inputs for agriculture. Though the country has made significant strides toward development of irrigation facilities since independence, more than 50 per cent of the agricultural land is still unirrigated. Further, huge variations are found across States in terms of the proportion of irrigated agricultural land. Punjab has an irrigation index of 98 per cent while only 6 per cent of the agricultural land in Jharkhand is irrigated (Chart 5). Further, large scale delays, huge cost escalation, implementation delays, etc. have contributed to slow down in expansion of areas under irrigation. Dwindling public sector control support for critical extension related activities and programme for land development and soil conservation are major gaps that need urgent redressal. These disparities in rural infrastructure too need to be addressed.

11. One significant component of rural finance is the value chain finance. It derives its significance from the fact that there are about 140 million farming households of which more than 80 per cent are small and marginal farmers. Linking these farmers to formal financial services is a significant challenge. If agriculture has to support investment for the small and marginal farmers, promoting agri-business through development of value chains looks very promising. Promoting agricultural value chains will bring about better market opportunities, technology adoption, private investments and reforms that would increase their access to finance besides significant positive impact on end-consumers in terms of reasonable prices of products. New generation private sector banks and foreign banks who have now priority sector obligations contribute a lot in this regard. NABARD has in the recent past, conducted some ground level studies to understand the supply chain management issues related to onion, potato & tomato and is now according priority to warehouse funding and creation of cold storage capacities in the country, besides providing negotiable warehouse receipts to the farmers which, in turn, will prevent distress sale of farm produce by the farmers.

12. It is widely recognised that commercial interests of small-scale producers are best bridged by producer organisations including co-operatives and their federations. Realising the importance of collective investments in productive assets, Government of India has set up Equity Grant Fund for providing matching assistance and credit guarantee fund (with 85 per cent default guarantee cover) for financing Farmer Producer Companies. The Reserve Bank has also included financing producer companies under the ambit of priority sectors. Further, NABARD has also constituted a Producer Organisation Development Fund with a corpus of ` 500 million for financing producer companies. Need of the hour is to scale-up the operations of the producer organizations.

Hassle-free financial services to the rural sector

13. Since independence, expanding the outreach of financial services to the poor has been at the centre of the poverty alleviation policy in India. The successive surveys of the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) {All-India Debt and Investment Surveys (AIDIS)} document a steady rise in the importance of banks as a source of rural household credit since 1951-52. While there was a decline in the share of banks in debt of rural households between 1991-92 and 2002-03, we can hope for a revival in this share over the last decade going by the extensive policy efforts for financial inclusion by the Reserve Bank and the Government of India in collaboration with institutions oriented towards rural areas, such as, the NABARD.

14. Financial inclusion is a buzzword nowadays, not just in India, but globally as well. At RBI, we view financial inclusion as a process that seeks to ensure access to appropriate financial products and services at an affordable cost in a fair, transparent & secure manner by mainstream institutional players. This availability of financial products and services is not only for society in general, but importantly, for the vulnerable groups, such as, weaker sections, small business units and low income groups as well. Such small customers do provide a big & stable market for retail deposits and other credit and third party products. Given the dominance of banks, bank-led model for financial inclusion has been emphasized, but at the same time, synergies embedded in non-bank financial players are also being tapped.

15. Several initiatives have been undertaken to expand banking services to remote areas of the country. The branch authorisation policy has recently been rationalised, with commercial banks directed to open not less than a quarter of their total branches in hitherto unbanked areas. Given the challenges involved in opening brick-and-mortar branches at a rapid pace due to resource and time constraints, banks have been encouraged to avail of Business Correspondents (BCs)/ Business Facilitators (BFs) to further their inclusion efforts. Further, the Reserve Bank has now removed some of the major restrictions on use of BC model; it has allowed for-profit NBFCs to work as BCs and the requirement of BC touch-point being within 30 km radius of the bank branch has been dispensed with. Banks have been persuaded to switch over to Core Banking Solutions (CBS) and leverage technology to the maximum extent possible. The growing focus on mobile technology to deliver banking services is a manifestation of this initiative. Similarly, importance being attached to non-banks and quasi-banks (“payment banks”, which are in the offing, can also function as BC of other banks), is also to be seen in the context of efforts to expand financial inclusion through technology based payment system products. With the cloud over Aadhar based unique identity being cleared, the pilots sponsored by the Reserve Bank for remittance related cash-outs using pre-paid instruments are expected to gather momentum and could turn out to be a major initiative in financial inclusion without the necessity of having bank accounts.

16. Since 2010, commercial banks have adopted Board-approved Financial Inclusion Plans (FIPs) containing self-set targets for financial inclusion for a span of three years. The first span of three years ending 2013 has been quite encouraging. Taking the process further, banks have been advised to draw up a 3-year FIP for the next three-year period, of which one year is already behind us. A key feature this time is that banks have been advised that their FIPs should be disaggregated to the branch level. The disaggregation of the plans is being done to ensure the involvement of all stakeholders in the financial inclusion efforts.

17. Having said all this, the present extent of financial inclusion does not adequately match up to our peers, not to mention the advanced economies (Table 2). For example in 2011, just 38 per cent of the adults had accounts at formal financial institutions in India as compared to over 50 per cent in other BRICS economies, and even higher in the United States. Of course, the statistics would have improved in the last three years given the policy push of the Government, the Reserve Bank and the stakeholders. Clearly, there is a substantial distance that we still need to cover to achieve universal financial inclusion.

Table 2: Select Financial Inclusion Indicators for 2011 |

|

Brazil |

Russia |

India |

China |

South

Africa |

United

States |

Account at a formal financial institution, older adults (%, age 25+) |

62.0 |

51.9 |

38.0 |

63.3 |

59.1 |

90.7 |

Loan from a financial institution in the past year, older adults (%, age 25+) |

8.1 |

8.5 |

8.8 |

7.9 |

11.8 |

21.6 |

{Source: World Bank(Global Findex)} |

18. In the last few years, there has been notable quantitative and qualitative improvement in the process of financial inclusion. Today, we have realized the need for deeper penetration of financial services in the unbanked sectors with more and more people using various modes of banking, such as, traditional brick & mortar, BCs/BFs channel, mobile banking, etc., to avail financial services. There are signs of financial inclusion graduating from a policy obligation to a business proposition. The concern, however, remains that still a large number of people remain excluded. For instance, formal credit to small and marginal farmers and small business units continue to be limited. Consequently, rural indebtedness from non-institutional sources among these farmers continues to be high. Thus questioning the efficacy of the players and their partnerships in creating a sustainable financial inclusion plan. At the same time, too much of mandated programmes for financial inclusion with focus on meeting quantitative targets and the perception that financial inclusion drives are meant to be doling out government subsidy only could degenerate the programme to the likes of some of the populist measures without sustainable business proposition for the providers and receivers of financial services. Hence, there is a need for careful planning and qualitative evaluation of these programmes. A specific case of concern is the growing fatigue in the SHG-Bank Linkage Programme, to which I turn now.

Issues in the SHG Bank Linkage Programme (SBLP)

19. India introduced the SHG-Bank Linkage Programme (SBLP) more than two decades back on a pilot basis. Today, it is a regular banking programme mainly due to active involvement of NABARD and also due to the role of the Reserve Bank in creating a conducive regulatory environment for this programme to grow. By end of March 2013, India had about 7.3 million bank-linked SHGs with a range of financial institutions including commercial banks, Regional Rural Banks, and co-operative banks, marginally down from 8 million recorded in 2012, exhibiting some signs of fatigue in this programme. Further, the number of SHGs having outstanding loans with banks has declined from 4.8 million to 4.4 million between 2011 and 2012 and stood at 4.5 million in 2013. Similarly, the number of SHGs to whom bank loans were disbursed declined from 1.6 million in 2010 to 1.2 million in 2011and has stagnated thereafter. (Table 3).

Table 3: Progress in Micro-Finance Programme by banks: Self Help Groups |

(as at end-March) |

|

Number (in millions) |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

2010-11 |

2011-12 |

2012-13P |

Loans disbursed |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

Loans outstanding |

2.9 |

3.6 |

4.2 |

4.9 |

4.8 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

|

Amount (` billion) |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

2010-11 |

2011-12 |

2012-13P |

Loans disbursed |

66 |

88 |

123 |

145 |

145 |

165 |

206 |

Loans outstanding |

124 |

170 |

227 |

280 |

312 |

363 |

394 |

{Source: NABARD} |

20. The major issues confronting the SHGs include inadequate number of quality agencies required for capacity building and hand-holding, governance and leadership challenges, lack of management information systems, inconsistent reporting, supervision and management capacities, excessive dependence on promoter agencies for essential services, skewed distribution of SHGs across the regions, decline of banking sector’s involvement in the programme with primacy being attached to financial inclusion programmes which have almost excluded SHGs from their focus, increasing incidence of NPAs, etc. The new challenges for SHGs are how do they move up in the value chain to livelihood activities leading to sustained income generation supported by different backward and forward linkages. Therefore, the focus needs to shift towards consolidation of SHGs by addressing these deficiencies. In order to overcome the fatigue of the SBLP and as part of its poverty alleviation strategy, NABARD has taken various initiatives like SHG-2, Joint Liability Groups (JLG) and Producer Organization related initiatives. It aims to cover all eligible poor rural households in the country through SBLP by March 2017 and promote 2 million new SHGs during 2013-17. There is also a strategic shift from State/district-based planning for SBLP to block-based planning to address the issue of intra-district imbalances in promotion of SHGs. There has also been a focus on convergence of SBLP with financial inclusion initiatives of the Reserve Bank and government programmes like the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) to maximise benefits to the SHG members. In respect of the latter, it is important to underscore that Government sponsored initiatives should not crowd out agencies already doing good work in the field as there is enough space for multiple stakeholders & SHGs to function. Focus on credit at the cost of savings should also not be over emphasized and distortions leading to misuse and abuse of the system through interest subvention also need to be avoided.

Concluding Thoughts

21. It has been repeatedly recognized that majority of the people in rural areas depend on agriculture as a source of living though non-farm activities are gradually gaining significance in the rural economic development. It is also recognized that agriculture is more risky economically than industry and trade and, therefore, the perception that rural populace are unbankable. Let us acknowledge that rural economy is imperfect, lacks information and communications infrastructure and coupled with geographical spread of rural population and diversity of need for small ticket size financial transactions, developing an inclusive rural financial system is a challenge. I have flagged some of the major challenges through a 7Ps framework involving issues of Product strategies, Processes, Partnerships among different players, Protection of both the providers and the receivers, Productivity of the financial services flowing to the rural sector, and capacity, competence and commitment of People involved in providing financial services. I am sanguine that none of these challenges are insurmountable and have reasons to believe that the seminar has provided several alternative solutions for achieving a sustainable financial inclusion in India.

22. Let me conclude by saying that the Reserve Bank remains committed to create a conducive regulatory environment where financial entities can ensure hassle free financial services to the poor without jeopardising financial stability. Contextually, banks may be given the freedom to determine their own financial inclusion strategies as part of their overall business philosophy and pursue it as a commercial activity, taking on board their risk appetite and product sophistication. With a couple of financial service providers, and especially an erstwhile microfinance service provider, allowed to become banks and with the possible introduction of on-tap licensing of small banks and payment banks in addition to entry of foreign banks in the context of priority sector requirements, we hope to expand the size and scope of the rural financial system landscape and, thereby, address the persistent and emerging challenges relating to rural finance and substantially improve the level of financial inclusion in the country, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Thank you all for your attention.

|