Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. It is a privilege to be here in Mumbai to deliver the 17th C.D. Deshmukh Memorial lecture. Thank you, Governor Das, for the kind invitation. Governor Deshmukh was both an extraordinary statesman and the Reserve Bank of India’s first Governor of Indian nationality. While presiding over the Bank’s transformation from an institute owned by private shareholders to a modern-day central bank, he drove initiatives to support rural credit, including channelling Reserve Bank funds to develop agriculture. These measures reflected Governor Deshmukh’s deep understanding of why financial inclusion matters. And, in his honour today, I would like to revisit the question of why financial inclusion belongs within the mandate of a central bank. My main thesis is that central banks and financial authorities can support and promote financial inclusion, first and foremost, by pursuing their core objectives. By watching over price stability, they ensure that money keeps its value. By ensuring financial stability, they prevent financial institutions from failing, and taking people’s savings with them. But most of all, central banks promote trust. By reinforcing trust in the financial system and its institutions, central banks bring ordinary people into the mainstream and help them reap its benefits. In this way, the central bank can help to catalyse a more inclusive and vibrant economy. It is thus a necessary condition for financial inclusion that central banks fulfil their core mandates. Yet it is not sufficient. Other elements too are important. New technology can play a crucial role in breaking down barriers for both citizens and financial institutions. To foster this process, central banks and financial authorities must provide the right infrastructure. This includes hard or physical infrastructure such as payment and settlement systems, as well as soft or ‘contextual’ infrastructure such as rules and guidelines that let the full benefits of the technology be captured while protecting its users. Central banks and innovators are vital partners: one cannot achieve financial inclusion without the other’s help. Today, I will begin by stressing the benefits of financial inclusion and taking stock of where we now stand. I will then touch on the role that central banks and financial authorities play in providing the necessary conditions for success. And I will suggest how they might build on this success by partnering with fintech, as we now call technology-driven innovation in financial services. Finally, I will outline how the BIS can help to foster international cooperation in this field. Why is financial inclusion important? Financial inclusion provides access to financial services that are the key to participating in a modern economy. These include payments, credit, insurance and savings. Without access to efficient payment systems, business grinds to a halt. A modern economy cannot work without efficient, reliable and cost-effective payments. Credit allows resources to be used more optimally over time. Credit from within the formal financial sector is typically cheaper and has better terms than informal credit, with all the problems arising from lender oligopolies and doubts about creditworthiness. In credit markets that are subject to such problems, market power can become entrenched. Black market lenders often run as monopolies and charge exorbitant interest rates. Informal markets are also incapable of providing insurance products, which can serve as a cushion against shocks such as bad harvests, illness, or the death of the main wage earner. Formal savings facilities can help generate low-risk interest income. Combined with formal credit facilities, they can help reduce fluctuations in consumer spending driven by income shocks. The poor stand to gain most from increased income stability and access to credit. While financial access does not guarantee financial engagement, it acts as an incentive. A basic deposit account opens the door to trying out other banking services, such as payments and credit. Furthermore, financial inclusion fosters ‘social inclusion’. For example, by depositing savings in a current account, individuals are protected by property rights. If they put their savings into jewellery or just stash money under the mattress, they may fall victim to theft or devaluations. Moreover, financial inclusion can make the transfer of welfare benefits faster, cheaper, and less prone to leakage. This benefits the state as well as the recipients. Overall, inclusion can help reduce poverty.1 Main barriers to inclusion Substantial progress has been made in expanding financial access. Since 2011, more than 1 billion adults have gained access to basic transaction accounts. Dedicated national strategies have played a big part. The Jan Dhan Yojana here in India sets an example.2 Yet more needs to be done globally, in terms of both expanding access and creating incentives for engagement. In terms of access, almost a third of the world’s adult population still lacks a basic deposit account (Chart 1, left-hand panel).3 In some countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas, only one adult in two has an account (Chart 2, bottom panel). On average, women, the poor, the unemployed and the less educated lag behind (Chart 1, centre panel). But even with satisfactory levels of financial access, engagement can remain low. For instance, according to the 2017 Global Findex Survey, fewer than half of the adults who had a bank account had actually saved with a financial institution in the preceding year. Even in high-income countries where most adults (94%) had an account, more than one in 10 preferred to borrow from family and friends. Barriers to inclusion have roots among users as well as service providers. The right-hand panel of Chart 1 highlights some of the reasons users give for not using financial services. Let me highlight the three barriers that public policy and innovation are most likely to overcome. The first barrier is ‘lack of trust’ in the financial system, and particularly in money and financial institutions. This can be due to a history of bank failures and the associated loss of hard-earned cash that people may have witnessed. Lack of trust may also reflect a lack of financial literacy. Indeed, people cannot be expected to trust something they do not understand. The second barrier is ‘high costs’. That is, a financial service may be too expensive for some users. There are two possibilities. Either the price is reasonable, but the user is too poor to afford it. Or the price really is too high because the service provider finds it unprofitable to serve some population segments. Consider a small, low-income community. Without a critical mass of potential customers, setting up a fully staffed branch may be too costly. Even if one ignores the fixed costs, the marginal profit from serving low-income clients with narrow financial needs may be too low. The third barrier is ‘lack of documentation’. Bank accounts cannot be opened without basic documents such as a birth certificate or identity card. Meanwhile, a blank credit record can block access to loans or insurance. Fortunately, public policy and innovation can help to overcome these barriers. I will start with how central banks and financial authorities can increase trust in the financial system. By fulfilling their mandates, central banks and financial authorities foster trust By looking after their core mandates – namely price and financial stability – central bank and financial authorities can bolster trust in the financial system, thus providing the basis for financial inclusion. This link is shown by the red arrow in Chart 3. Fundamentally, people will not start using formal financial services if they do not trust the currency, or financial institutions such as banks, credit unions and cooperatives. Central banks can help build trust in both these dimensions. Safeguarding price stability builds trust in the currency, and a sound prudential supervision framework builds trust in institutions. At the end of the day, trust comes down to making credible promises and delivering on them. And that trust is hard to win but easy to lose. Central banks thus need to stay fully focused on their mandates. Let me start by commenting on why the price stability mandate matters. First, rising prices can undermine people’s trust in fiat money, even before they accelerate into the double digit range. As Chart 4 shows, trust is undermined even at ‘normal’ inflation rates. The so-called inflation tax weighs more heavily on the poor, whose savings are disproportionately hurt by rapid price increases.4 The rich and more sophisticated have better access to financial instruments that hedge in some way against inflation, whereas the poor are likely to hold a larger share of cash or transactional balances that do not earn interest. Relative to the rich, the poor also depend more on state-determined income such as minimum wages or pensions that are not fully indexed to inflation. Second, price instability can also undermine deposit and credit markets. When inflation roars, people avoid saving at fixed interest rates, because a jump in inflation would destroy the value of their savings. On the other hand, borrowers shy away from variable interest rate loans, because high inflation means volatile inflation, and potentially higher real rates of interest, making for greater uncertainty in the repayment schedule. As savers and borrowers cannot agree on terms, the corresponding markets collapse, eroding financial inclusion. The damage can quickly spread to other financial services, such as insurance. If no one knows what the currency will be worth when future claims are paid, why would anyone buy insurance today?  Financial stability is another pillar of financial inclusion. The resilience of institutions is as important as that of the financial system. If a rural cooperative bank fails, for example, its customers may well lose faith in the system too. Such failures may stem not only from poor banking practice, but also from inadequate deposit insurance, regulation and supervision – all of which erode trust.5 Imagine then what a system-wide crisis can do to public confidence. Financial crises also raise borrowing costs, leading to a credit crunch and recession. The evidence suggests that banks cut their lending sharply in the wake of the 2007–09 Great Financial Crisis.6 Credit may be cut off for some or become unaffordable for others. As a result, individuals and firms may be forced to look outside the formal financial system. In this way, financial crises further raise the barriers to inclusion. Before moving on, let me stress that there is a two-way relationship between price and financial stability on the one hand, and financial inclusion on the other. This link is described by the grey arrow in Chart 3. Financial inclusion can help central banks and financial authorities reach their goals. With a broader base of depositors and borrowers across regions and demographics, financial institutions can better diversify their sources of funding and lending opportunities.7 And this makes them safer. Innovation for inclusive finance While price and financial stability help to resolve trust-related barriers to financial inclusion, they cannot promote financial inclusion on their own. Among other factors, such as an adequate legal system, technology and innovation are needed too. Digital technology and big data, in particular, are key to overcoming the other barriers to financial inclusion, namely the high costs of financial services, and potential users’ lack of documentation and credit history. When it comes to cutting costs, web and smartphone-based financial services have proved to be most effective. From M-Pesa in Kenya to Alipay in China and PayTM in India, technology has brought financial services literally to our fingertips. First, digital technology offers the cheapest delivery channel for financial services. Second, digital networks expand the circle of users, creating positive network effects. Third, mass smartphone ownership lets financial service providers reach a huge number of potential customers (Chart 5, left-hand panel). Digital financial service platforms can thus be scaled up at virtually zero marginal cost. In China, for instance, digital payment platforms like AliPay let users seamlessly buy insurance or invest wallet balances in mutual funds. Cost reductions could also be realised in cross-border services such as remittances. At the same time, advances in data generation, collection, and processing can overcome the problems arising from a lack of documentation or credit history among some sectors in the economy. The right-hand panel of Chart 5 shows that fintech credit has expanded rapidly on the back of these advances. Indeed, big techs – large technology firms – are already processing data collected via their digital platforms in order to offer credit to borrowers whom banks find too risky. A case in point is Ant Financial’s MYbank, which recently teamed up with a traditional bank to better serve small off-line farmers. MYbank gives farmers in rural areas QR code posters that customers scan in order to pay the farmers via Alipay. The bank then uses transaction data to score and offer credit to the farmers, who typically lack the documentation needed to access regular bank credit. In effect, ‘newly created data serves as the collateral’. This represents a substantial advance in financial inclusion.8  Advances in biometrics-based identity programmes are also helping to break down the documentation barrier. With such advances, individuals can use their fingerprints or a retina scan to obtain an identity card. In this regard, India’s Aadhaar programme is a huge asset, and one that is already delivering benefits. Via the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System, or AePS, people in rural areas with few bank branches can make deposits, withdrawals and transfers. Basically, this system allows banking correspondents to visit rural areas with a micro ATM that can verify customers’ identities digitally and operate their accounts. Innovation can pose risks too Needless to say, there is a less benign side to new technology. One potential market failure is excessive market concentration. Once a large digital network is established, potential competitors have little scope to build rival networks and challenge the incumbent. The fixed cost of setting up a new network would be excessive. Also, dominant platforms may seek to consolidate their position by raising the barriers to entry. When a network operator owns a smartphone-based payment system, for example, it can charge potential competitors, such as banks, a connection fee that will prevent new entrants from competing effectively. Once they have a captive user base, dominant platforms can then jack up the price of their financial services. So, although new technologies cut the cost barriers to financial inclusion, market concentration can work in the opposite direction. A second market failure arises from the control of customer data. When big tech firms – such as Ant Financial, Tencent or Mercado Libre – collect detailed information about their customers, they become – at least, to date – the sole owners of that data. This can be seen as a by-product of the services provided by big techs. Given that such data are free and non-rival – that is, usable by many without loss of content – it would be socially desirable to share it. But big tech firms have no incentive to do so. On the contrary, data give them an informational advantage over competitors. Using privileged data, for example, they can assess a potential borrower’s creditworthiness, and even a person’s reservation rate – the highest interest rate at which a borrower would be willing to take out a loan. Based on this, a big tech firm can charge higher lending rates, up to the individual reservation rates, extracting a larger share of the surplus from its customers. Proprietary control of data thus amplifies big techs’ market power. Financial innovation also creates new vulnerabilities. Criminals, notably, can exploit the anonymity conferred by some digital platforms and the absence of supervisory oversight. Policymakers can help address the market-failures and risks posed by innovation For financial innovation to promote financial inclusion further, its potential adverse effects must be addressed. Policymakers can play a vital role here by upgrading or providing new infrastructure, both hard and soft. Hard infrastructure comprises the systems and utilities that support financial services. Setting up utilities such as settlement systems or agreeing on common technical standards, for example, may be beyond the capacity of market participants. Yet, such infrastructures are desirable because they can reduce transaction costs and level the playing field. When the market fails to provide for the public good, central banks and financial authorities can act as catalysts. Take India’s Unified Payments Interface: this facility allows both domestic and global players to develop mobile payment applications. As such, it lowers the barriers to entry, especially for smaller firms, thus levelling the playing field. Another way to foster competition is via regulatory sandboxes. They let innovators test their new products under regulatory oversight. Meanwhile, innovation hubs provide a forum for knowledge-sharing, competition or even fund-raising. Thus, hubs and sandboxes help to ensure a dynamic financial landscape – one that is not necessarily dominated by just a few players. They can also give regulators valuable insights into the latest financial innovation trends, which can help them design an adequate regulatory response. A sound regulatory framework can also smooth the path to market entry. Many central banks, including the Reserve Bank, are setting up such structures. Policymakers are also responsible for the soft infrastructure, which includes the regulations, standards or programmes that guide the provision of financial services, and mitigate risks – such as those arising from the collection and use of data, fraud and money laundering. To start with data-related issues and as an example, I would like to consider buying a book on Amazon using a credit card. Who should own the transaction data – me, Amazon, or the credit card company? Should companies be allowed to match my transaction data with personal information from my linked devices? What should they be allowed to do with such data? These are questions with both an ethical and economic angle. For instance, data ownership is already severely concentrated among a few big firms, giving them an excessive degree of market power. And, in many cases, customers are blissfully unaware of how their data are being used. Dealing with these issues is complicated by the inadequacy of existing rules. So far, the policy response has been uncoordinated. Some countries have passed, or are considering, data privacy laws. Among these are Australia, the EU, Singapore and Switzerland. To increase data portability and foster competition, an increasing number of countries are also adopting some form of ‘open banking’ requirement.9 The core idea is that consumers should have the right to authorise a third party, such as a fintech firm, to access their financial data. The fintech firm would then use the data to offer competing financial services. A related issue is cyber security and money laundering. An emphasis on formal financial systems and services is often viewed as crucial to addressing this type of risk. One challenge is how to effectively apply existing anti-money laundering mechanisms to digital financial services, but without hindering financial inclusion. Mexico’s recent ‘Fintech Law’ is a good example. It adopts the ‘same-risk-same-regulation’ principle, and requires fintech institutions, like banks, to take all possible measures to prevent and detect transactions that involve illegally obtained resources or support the financing of terrorism. Conclusions Financial inclusion is the gateway to increased prosperity. Central banks play a key role simply by fulfilling their price and financial stability objectives. At the same time, innovation and technology are needed too. Because financial innovation can have adverse effects too, it must be guided as well as supported. Policymakers can help by providing adequate infrastructure. This takes the form of both hard infrastructure such as payment systems or clearing houses, and soft infrastructure consisting of rules, regulations and standards. Policy initiatives should be coordinated across borders, especially in the case of innovations that matter for financial inclusion. Coordination is needed because both innovation and data flow across borders. Remittance services that take advantage of new distribution channels are a highly relevant example. Remittances are an important source of income, especially in emerging market economies. Moreover, as formal remittances are cheaper than informal ones, they provide a compelling reason for individuals to be financially included. A joint study on how digital technology can enhance cross-border payments was recently published by the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada, and the Monetary Authority of Singapore.10 Economies of scale are just one advantage of such applications. The BIS is determined to contribute substantially in this area. Our new medium-term strategy, Innovation BIS 2025, embraces several initiatives that we hope will deliver insights into technological developments for the financial system and help policymakers use them effectively. For example, we plan to establish a multidisciplinary Innovation Hub to foster collaboration in innovation-related work. A new unit will do policy analysis and research on how innovation and increased data availability could shape the response of central banks. The challenges posed by financial innovation show that we need to broaden our collective efforts and integrate data into policy considerations. Defining standards and deciding who should have access to data and how best to manage them are important aspects to consider. Getting the answers right could lessen the scope for regulatory arbitrage and adverse spillovers, keep markets competitive, and channel more of the benefits of innovation towards financial inclusion. International cooperation is vital to ensure that technology reshapes financial intermediation for the better. Since those pioneering efforts by Governor Deshmukh and the RBI, India has made huge advances in the field of financial inclusion. The role of central bank and government policies in driving this progress cannot be overemphasised. Yes, there is more to be done. As an old proverb has it: ‘We can’t change the wind’s direction, but we can always trim the sails’. Thank you for your attention.

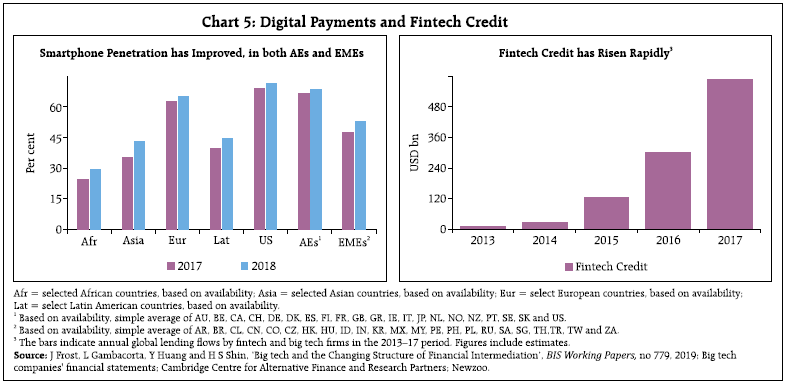

|