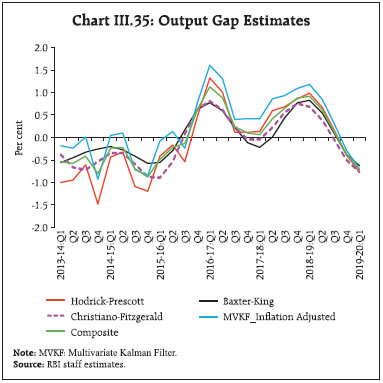

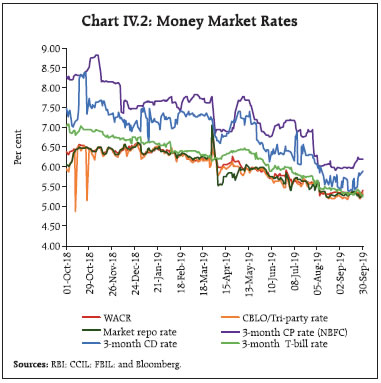

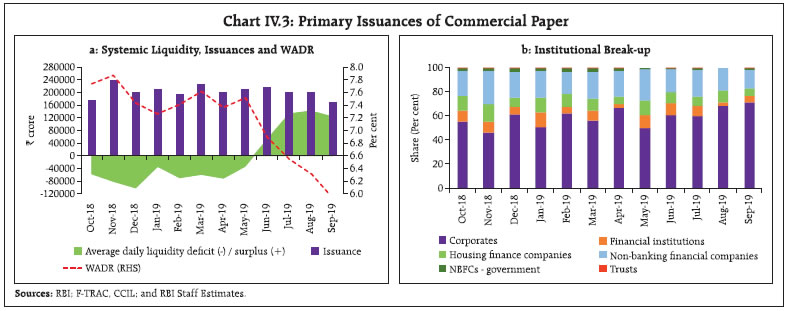

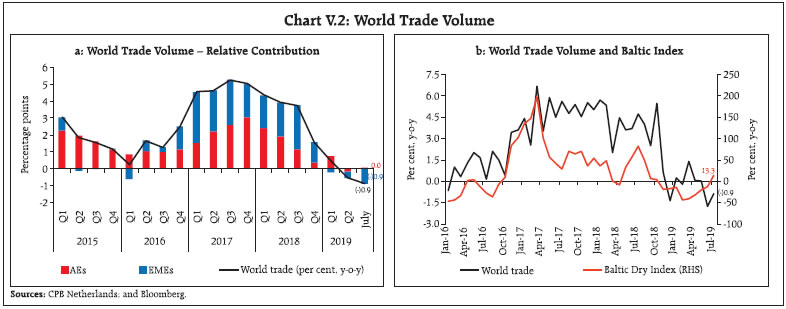

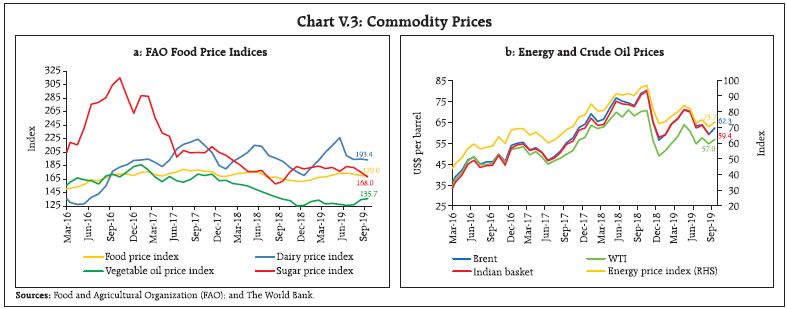

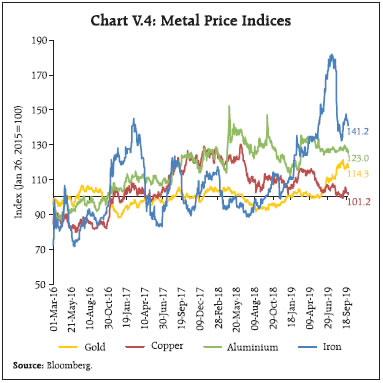

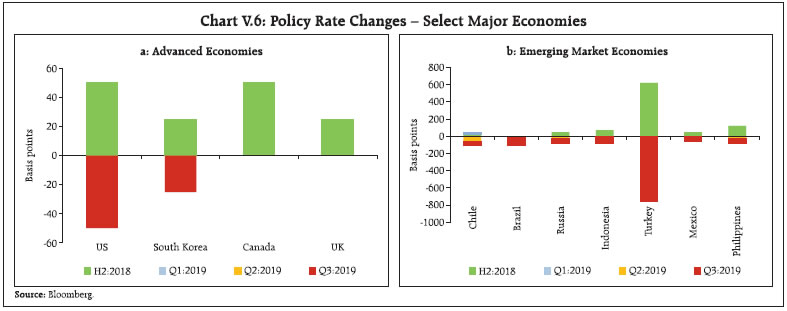

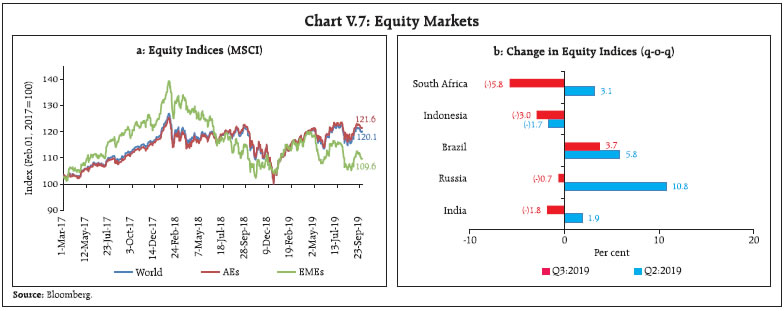

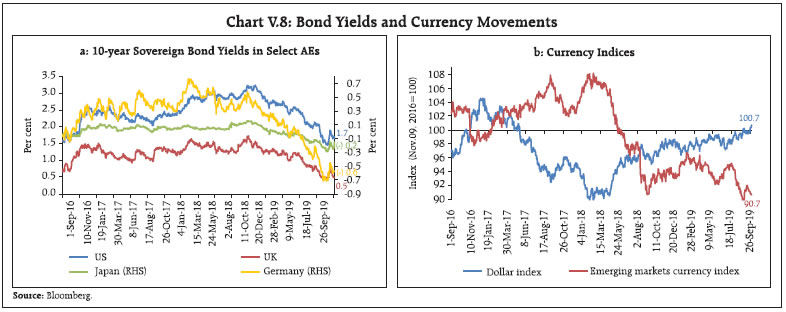

| I. Macroeconomic Outlook The slowdown in domestic economic activity that started in 2018-19 extended into the first half of 2019-20. Headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation is projected to remain below target over the rest of 2019-20 and the early months of 2020-21. Real gross domestic product (GDP) growth is expected to recover in H2:2019-20, facilitated by favourable base effects and transmission of past monetary policy actions. A slew of measures by the government impart an upside to growth prospects. Intensification of global uncertainty around US-China trade tensions, a hard Brexit and geo-political tensions are key downside risks to the baseline growth path. I.1 Key Developments since April 2019 MPR Since the release of the Monetary Policy Report (MPR) of April 2019, global economic activity has weakened further. Several downside risks flagged in the April MPR appear to be materialising: escalation of trade tensions; growing probability of a disorderly Brexit; volatility in crude oil prices; and a risk-on risk-off sentiment in financial markets on tumultuous geo-political and economic events. In their wake, global growth has lost the momentum it had gathered in Q1:2019. Central banks across advanced economies (AEs) and emerging market economies (EMEs) are easing monetary policy in counter-cyclical defence. Global trade has sunk into contraction, with knock-on effects impacting investment and industrial production, especially manufacturing. Reflecting this, commodity prices slumped, with crude oil prices tumbling in August and gold prices surging on safe haven demand. Foreign exchange markets turned volatile, following the depreciation of the Chinese renminbi in early August. Crude oil prices were bolstered temporarily in mid-September by the attack on Saudi Arabian oil facilities and disruption to global oil supplies. Domestically, the slowdown in economic activity that started in 2018-19 extended into the first half of 2019-20. Real GDP growth fell to a 25-quarter low in Q1:2019-20 on weak private consumption and investment and high frequency indicators for Q2 point to a slowdown in the various constituents of aggregate demand deepening. Some green shoots are emerging though in agriculture and allied activities. The initial delay and deficiency in the south-west monsoon has been mitigated by the resurgence of rains during July-September. Comfortable reservoir levels augur well for rabi sowing and foodgrains stocks above the buffer norms provide a cushion against potential inflationary pressures. Meanwhile, headline CPI inflation remains below target. While food inflation has edged up since March 2019, inflation excluding food and fuel has undergone a broad-based moderation. Monetary Policy Committee: April-August 2019 During April-August 2019, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) met thrice in accordance with the bi-monthly schedule. In the April meeting, the MPC cut the repo rate by 25 basis points (bps) to 6.0 per cent (with a majority vote of 4-2) to strengthen domestic growth impulses by spurring private investment, while maintaining a neutral stance (with a majority vote of 5-1). With signs of weakening of growth impulses even further widening the negative output gap, and with headline inflation projected to remain below the target over the next 12 months, the MPC voted unanimously to reduce the repo rate by another 25 bps in its June 2019 meeting and changed the stance of monetary policy from neutral to accommodative. In its August meeting, the MPC reduced the policy repo rate by a further 35 bps to 5.40 per cent on signs of accentuation of the slowdown in domestic activity amidst deteriorating global growth and escalating trade tensions posing downside risks to the outlook. With the inflation outlook projected to be benign and within the target over the forecast horizon, all members of the MPC voted unanimously to reduce the policy rate (4 members for a reduction of 35 bps and two for 25 bps) and to maintain an accommodative stance. The MPC was of the view that the standard 25 bps cut might prove to be inadequate in view of evolving global and domestic macroeconomic developments, while a 50 bps reduction might be excessive, especially taking into account the actions already undertaken. Overall, the MPC reduced the policy repo rate by a cumulative 85 bps during April-August, in addition to the reduction of 25 bps in February. The MPC’s voting pattern reflects the diversity in individual members’ assessments, expectations and policy preferences, a feature that is reflected in voting patterns of the MPC in other central banks (Table I.1). Macroeconomic Outlook Chapters II and III analyse the macroeconomic developments during April-September 2019 and explain deviations of inflation and growth outcomes vis-à-vis staff’s projections. Turning to the outlook, the evolution of key macroeconomic and financial variables over the past six months warrants revisions in the baseline assumptions (Table I.2). | Table 1.1: Monetary Policy Committees and Voting Pattern | | Country | Policy Meetings: April 2019 - September 2019 | | Total Meetings | Meetings with Full Consensus | Meetings with Dissents | | Brazil | 4 | 4 | 0 | | Chile | 4 | 3 | 1 | | Czech Republic | 4 | 2 | 2 | | Hungary | 5 | 5 | 0 | | Israel | 4 | 1 | 3 | | Japan | 4 | 0 | 4 | | South Africa | 3 | 2 | 1 | | Sweden | 3 | 3 | 0 | | Thailand | 4 | 3 | 1 | | UK | 4 | 4 | 0 | | US | 4 | 1 | 3 | | Sources: Central bank websites. |

| Table I.2: Baseline Assumptions for Near-Term Projections | | Indicator | MPR (April 2019) | Current MPR (October 2019) | | Crude oil (Indian basket) | US$ 67.0 per barrel during 2019-20 | US$ 62.6 per barrel | | Exchange rate | ?69/US$ | ?71.3/US$ | | Monsoon | Normal for 2019 | 10 per cent above long period average | | Global growth | 3.5 per cent in 2019

3.6 per cent in 2020 | 3.2 per cent in 2019

3.5 per cent in 2020 | | Fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | To remain within BE 2019-20

Centre: 3.4

Combined: 5.9 | To remain within BE 2019-20

Centre: 3.3

Combined: 5.9 | | Domestic macroeconomic/ structural policies during the forecast period | No major change | No major change | Notes: 1. The Indian basket of crude oil represents a derived numeraire comprising sour grade (Oman and Dubai average) and sweet grade (Brent) crude oil.

2. The exchange rate path assumed here is for generating staff’s baseline growth and inflation projections and does not indicate any ‘view’ on the level of the exchange rate. The Reserve Bank is guided by the objective of containing excess volatility in the foreign exchange market and not by any specific level of and/or band around the exchange rate.

3. Global growth projections are from the World Economic Outlook (January and July 2019 Updates), International Monetary Fund (IMF).

4. BE: Budget estimates.

5. Combined fiscal deficit refers to that of the Centre and States taken together.

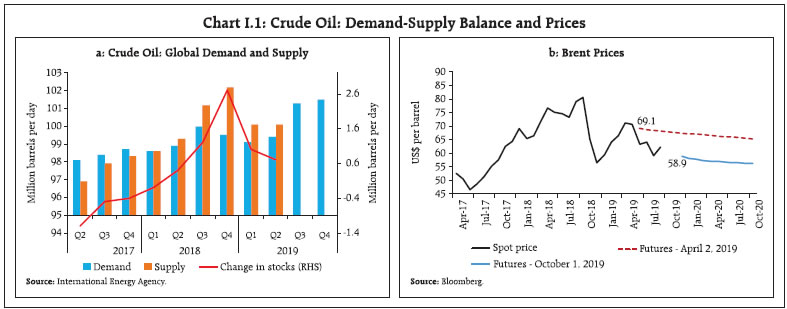

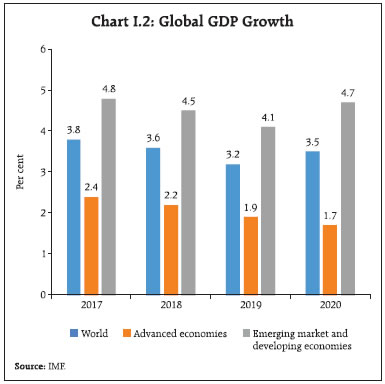

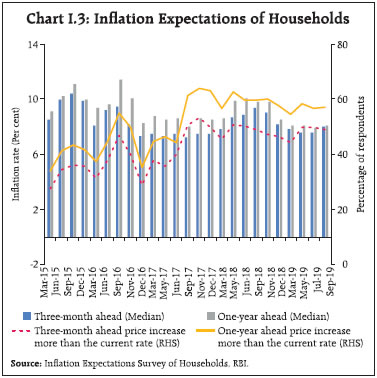

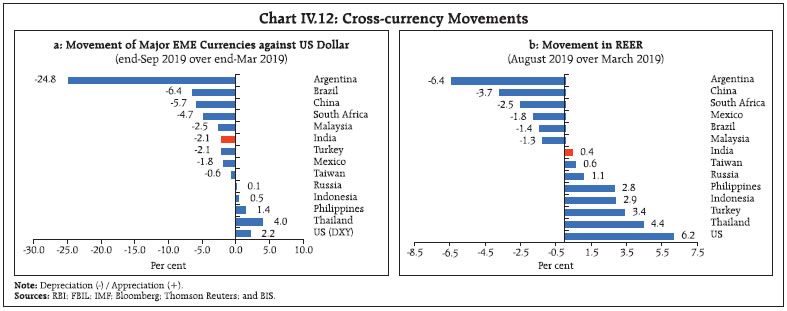

Sources: RBI staff estimates; Budget documents; and IMF. | First, international crude oil prices declined between mid-May and mid-September reflecting weakness in global demand amidst excess supply conditions and large stockpiles, despite geo-political tensions and production cuts by the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) (Chart I.1). Crude oil prices hardened temporarily in the second half of September following disruptions to production in Saudi Arabia. Given the current demand-supply assessment, the baseline scenario assumes crude oil prices at an average of US$ 62.6 per barrel.  Second, the nominal exchange rate (Indian rupee, INR vis-à-vis the US dollar) has depreciated from its April level, especially during August, impacted by a drop in the Chinese renminbi below the psychological level of 7 yuan per US$ in the wake of an escalation in US-China trade actions. A generalised flight to safety towards the US dollar assets and portfolio capital outflows also amplified pressures on the rupee. The rupee came under renewed pressure in mid-September following the spike in crude oil prices but recovered in subsequent days following the announcement of various measures by the government to boost investment and growth and to stabilise the flow of funds into the capital market. Third, the weakening of global economic activity and trade is confirmed by the global manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) remaining in contraction zone in September 2019 at 49.7, the World Trade Organisation's Goods Trade Barometer indicating weakness in merchandise trade persisting in Q3:2019 and downgrades to global growth projections by various agencies. Against this backdrop, global growth for 2019 and 2020 is now expected to be below the April baseline (Table I.2 and Chart I.2). I.2 The Outlook for Inflation Headline CPI inflation has remained below target so far in 2019-20. Importantly, inflation excluding food and fuel has softened across major goods and services, reflecting the slowdown in domestic demand. Looking ahead, inflation expectations feed into future inflation through price and wage contracts. One-year ahead inflation expectations of urban households increased by 20 bps over the previous round in the September round of the survey conducted by the Reserve Bank; three-month ahead inflation expectations moved up by 40 bps during this period (Chart I.3).1 According to the Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey for September, inflation expectations moderated from the previous round.

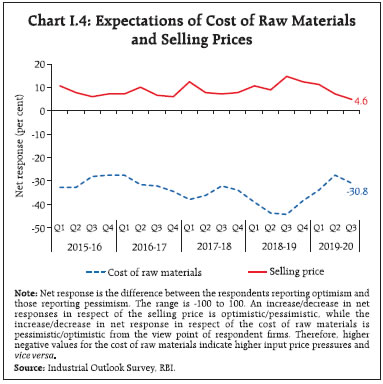

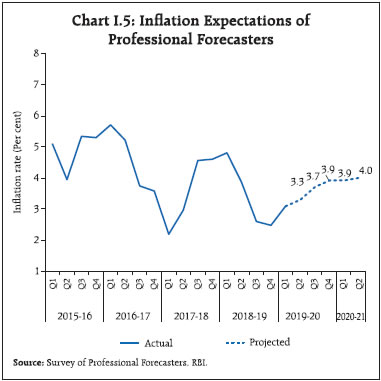

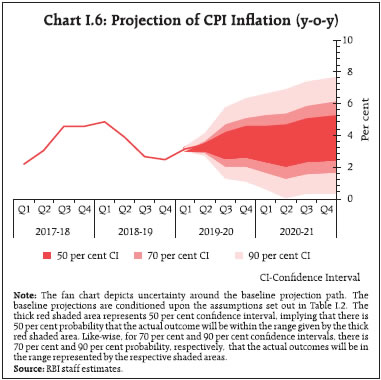

Manufacturing firms polled in the July-September 2019 round of the Reserve Bank’s Industrial Outlook Survey (IOS) expected an increase in the cost of raw materials and muted selling prices in Q3:2019-20 (Chart I.4).2 According to the purchasing managers’ survey for manufacturing firms, input prices eased in September due to weak demand for raw materials and semi-finished items; output prices registered a marginal increase. Services sector firms reported lower input prices and higher output prices in August. Professional forecasters surveyed by the Reserve Bank in September 2019 expected CPI inflation to increase from 3.2 per cent in August 2019 to 3.9 per cent in Q4:2019-20 and to 4.0 per cent in Q2:2020-21 (Chart I.5).3 Taking into account the initial conditions, the signals from forward-looking surveys and estimates from time-series and structural models, CPI inflation is projected at 3.4 per cent in Q2:2019-20, 3.5 per cent in Q3, and 3.7 per cent in Q4, with risks evenly balanced (Chart I.6). The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for headline inflation in Q4:2019-20 are 2.7-4.7 per cent and 2.2-5.3 per cent, respectively. For 2020-21, assuming normal monsoon and no major exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates indicate that inflation will move in a range of 3.5-4.0 per cent. The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for Q4:2020-21 are 2.5-5.4 per cent and 1.8-6.2 per cent, respectively.

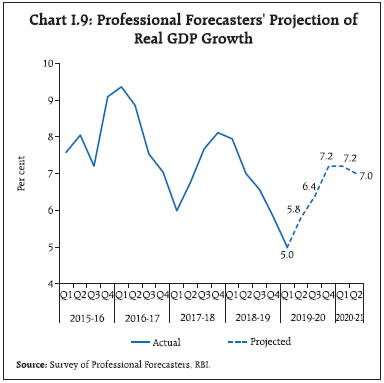

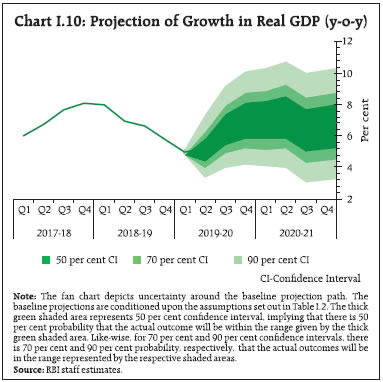

There are both upside and downside risks to the baseline inflation forecasts. The upside risks include: volatility in international and domestic financial markets from trade tensions, Brexit and monetary policy stances of the major AEs; supply disruptions in the global crude oil market due to geo-political tensions; and, sudden spikes in the prices of perishable food items. Downside risks could emanate from more than assumed softening in crude oil and other commodity prices due to sluggish global demand, and weaker inflation excluding food and fuel domestically due to depressed domestic demand conditions. I.3 The Outlook for Growth As indicated earlier, domestic economic activity turned out to be weaker in H1:2019-20 vis-à-vis projections in the April 2019 MPR in an environment of global headwinds. The expected pick-up in both private consumption and investment failed to materialise, and exports lost momentum under the weight of the slump in world trade. Although the south-west monsoon turned out to be above long period average, its uneven progress – both temporal and spatial – could impinge upon the prospects for agriculture. Turning to the outlook, consumer confidence for the year ahead moved lower in the May, July and September rounds of the Reserve Bank’s survey, due to ebbing of sentiments on the general economic situation and the employment scenario (Chart I.7).4 Sentiment in the manufacturing sector polled in the July-September 2019 round of the Reserve Bank’s IOS dipped for the quarter ahead, reflecting moderation in expected production, order inflows, capacity utilisation, employment conditions and exports (Chart I.8). Surveys by other agencies of future business expectations indicate a mixed picture (Table I.3). Firms in the manufacturing and services sectors polled in the Nikkei’s purchasing managers’ surveys were optimistic about one-year ahead output prospects. In the September 2019 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey, professional forecasters expected real GDP growth to recover from 5.0 per cent in Q1:2019-20 to 7.2 per cent in Q4:2019-20 and then moderate to 7.0 per cent in Q2:2020-21 (Chart I.9). Taking into account the baseline assumptions, survey indicators, the reductions in the policy repo rate since February 2019, the base effects and model forecasts, real GDP growth is projected at 6.1 per cent in 2019-20 – 5.3 per cent in Q2, 6.6 per cent in Q3, 7.2 per cent in Q4 – with risks evenly balanced (Table I.4). For 2020-21, the structural model estimates indicate real GDP growth at 7.0 per cent – quarterly growth rates in the range of 6.5-7.4 per cent – assuming a normal monsoon, and no major exogenous or policy shocks. | Table I.3: Business Expectations Surveys | | Item | NCAER Business Confidence Index (July 2019) | FICCI Overall Business Confidence Index (June 2019) | Dun and Bradstreet Composite Business Optimism Index (July 2019) | CII Business Confidence Index (September 2019) | | Current level of the index | 121.8 | 59.6 | 70.0 | 52.5 | | Index as per previous survey | 115.4 | 60.3 | 78.4 | 59.6 | | % change, q-o-q | 5.5 | -1.2 | -10.7 | -11.9 | | % change, y-o-y | 6.5 | -16.1 | -13.2 | -19.1 | Notes: 1. NCAER: National Council of Applied Economic Research.

2. FICCI: Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry.

3. CII: Confederation of Indian Industry. |

| Table I.4: Projections - Reserve Bank and Professional Forecasters | | (Per cent) | | | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | | Reserve Bank’s Baseline Projection | | | | Inflation, Q4 (y-o-y) | 3.7 | 4.0 | | Real GDP Growth | 6.1 | 7.0 | | Median Projections of Professional Forecasters | | | | Inflation, Q4 (y-o-y) | 3.9 | 4.0# | | Real GDP growth | 6.2 | 7.0 | | Gross domestic saving (per cent of GNDI) | 30.1 | 30.5 | | Gross capital formation (per cent of GDP) | 31.0 | 31.0 | | Credit growth of scheduled commercial banks | 12.0 | 12.9 | | Combined gross fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | 6.1 | 6.0 | | Central government gross fiscal deficit (per cent of GDP) | 3.3 | 3.3 | | Repo rate (end-period) | 5.0 | - | | Yield on 91-days treasury bills (end-period) | 5.2 | 5.4 | | Yield on 10-year central government securities (end-period) | 6.3 | 6.5 | | Overall balance of payments (US$ billion) | 15.1 | 10.0 | | Merchandise exports growth | 1.5 | 6.3 | | Merchandise imports growth | 0.5 | 7.1 | | Current account balance (per cent of GDP) | -1.9 | -2.0 | Note: GNDI: Gross National Disposable Income.

#: Q2:2020-21.

Source: RBI staff estimates; and Survey of Professional Forecasters (September 2019). |

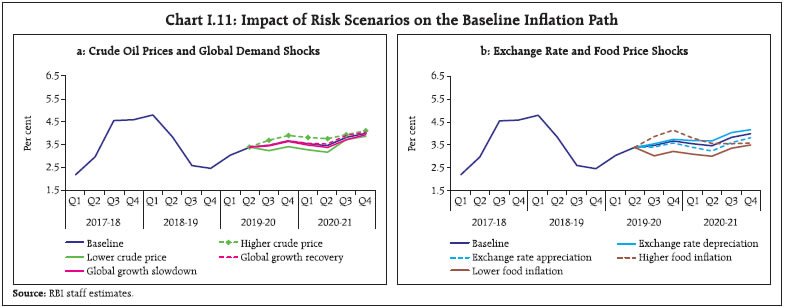

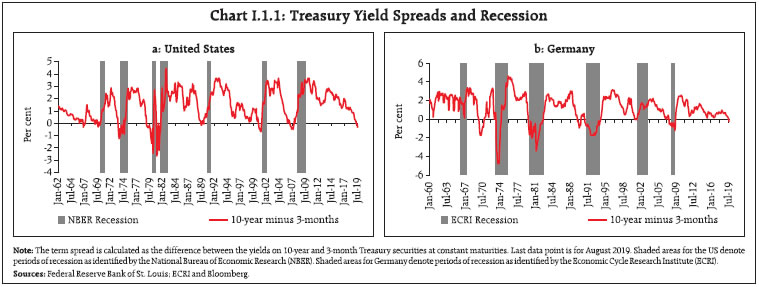

There are upside as well as downside risks to the baseline growth scenario (Chart I.10). The measures announced by the government in August-September to boost growth and investment – policy reforms on foreign direct investment (FDI), upfront release of funds for recapitalisation of public sector banks (PSBs), merger of PSBs, incentives for exports and real estate, reduction in the corporate income tax rate – along with a faster resolution of stressed assets, and a faster pace of transmission of past repo rate cuts by banks to their lending rates impart an upward bias to the baseline growth projection path. However, further escalation of trade tensions, a hard or no-deal Brexit and increased volatility in global financial markets pose downside risks to the baseline growth path. I.4 Balance of Risks The baseline projections of inflation and growth in the preceding sections are conditional on the assumptions relating to the key variables set out in Table I.2. Uncertainties surrounding these assumptions could lead to upward and downward deviations from baseline projections. This section assesses the balance of risks to the baseline projections in plausible alternative scenarios. (i) Global Growth Uncertainties The baseline scenario assumes a slowdown in external demand in 2019 and 2020. Yield curve inversion in major AEs has raised concerns about the growth outlook (Box I.1). Global growth could turn out to be weaker if there is further escalation of trade tensions, a hard/no-deal Brexit, a greater-than-envisaged slowdown in some major economies like China, or a combination of these factors. In such a scenario, if global growth slips down by 50 bps vis-à-vis the baseline, domestic growth and inflation could be lower by around 20 bps and 10 bps, respectively, from their baseline trajectories (Charts I.11a and I.12a). Conversely, an expeditious and orderly resolution of trade tensions, and/or a smooth Brexit could boost confidence and provide support to global trade and demand. Should global growth surprise by 50 bps on the upside, domestic growth and inflation could edge higher by around 20 bps and 10 bps, respectively.

Box I.1: Does Yield Spread Predict Output Growth? The spread between yields on the US 10-year and 3-month treasury securities – a closely watched metric for term spread – has inverted for the first time since 2007 and turned negative at 13 basis points (bps) in June 2019. The spread has remained in negative territory for the third consecutive month in August at 35 bps (from 83 bps a year ago). Since the 1950s, US recessions have been preceded by sizeable inversions in the yield curve. The only occasion when the 3-month Treasury security yield exceeded the 10-year Treasury yield without the occurrence of a subsequent recession was in September 1966. Barring this, yield curve inversion has coincided with a recession in the following 18-24 months (Chart I.1.1a). Inversion/narrowing of yield spreads has occurred in other AEs. Yields have flattened in Germany, the UK, Japan, Singapore and Australia, mirroring a slowdown in the global economy. In the case of Germany, the spread of the 10-year bond yield over the 3-month bond yield turned negative falling to 24 bps in August 2019 as compared with 61 bps a year ago. Germany experienced recessions beginning in 1966, 1973, 1980, 1991, 2001 and 2008. All recessions, except the 1966 recession, were preceded by a sharp decline in long-term Treasury security yields relative to short-term yields. The only inversion that was not followed by a recession was in 1970 (Chart I.1.1b).  According to the expectations hypothesis of the term structure, long-term interest rates equal the sum of current and expected future short-term interest rates plus a term premium. The term premium explains why the yield curve usually slopes upwards, i.e., yields on long-term securities usually exceed those on short-term securities. The yield curve flattens or inverts/slopes downward when the public expects short-term interest rates to fall. In such a scenario, investors bid up the prices of longer-term securities causing a fall in long-term yields relative to yield on short-term securities. There is no unanimity, however, on the theoretical relationship between the term spread and economic activity. To a large extent, the usefulness of the spread for forecasting economic activity remains a “stylised fact in search of a theory” (Benati and Goodhart, 2008). Moreover, the predictive power of the term spread for output growth depends on monetary policy objectives and the reaction function used. In the case of monetary policy tightening for example, short-term rates are likely to rise more than long-term rates and cause the yield curve to flatten or possibly invert (Feroli, 2004). It is also argued that the term spread forecasts output growth better, the more responsive the monetary authority is to deviations of output from potential. The spread forecasts less accurately if monetary policy focusses exclusively on controlling inflation. The consumption smoothing model derives a relationship between the slope of the yield curve and future economic activity by assuming that individuals prefer stable consumption rather than high consumption during periods of rising income and low consumption when income is falling (Harvey, 1988). If they expect a recession in the future, consumers sell short-term financial instruments and purchase bonds at a discount to generate income, resulting in a flattening or inversion of the yield curve. | Table I.1.1: Correlation between GDP Growth and Yield Spreads | | | Lagged Yield Spread | | Future Yield Spread | | Country | t-6 | t-5 | t-4 | t-3 | t-2 | t-1 | t | t+1 | t+2 | t+3 | t+4 | t+5 | t+6 | | US | 0.136 | 0.192 | 0.218 | 0.213 | 0.229 | 0.154 | 0.041 | -0.073 | -0.166 | -0.204 | -0.231 | -0.341 | -0.360 | | | (0.042) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.021) | (0.545) | (0.278) | (0.013) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | | Germany | 0.268 | 0.272 | 0.307 | 0.291 | 0.322 | 0.119 | -0.026 | -0.207 | -0.372 | -0.385 | -0.400 | -0.418 | -0.311 | | | (0.037) | (0.034) | (0.016) | (0.023) | (0.011) | (0.361) | (0.843) | (0.110) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.015) | Notes: 1. Yield spread between 10-year and 3-month Treasury securities has been measured as the quarterly average of monthly observations.

2. Data for the US and Germany pertain to the period Q2:1962–Q2:2019 and Q4:2002–Q2:2019, respectively.

3. Figures in the parentheses represent p-values.

Sources: Bloomberg; and RBI staff estimates. | The empirical literature suggests that the yield spread predicts output growth at a four-to-six-quarter horizon with considerable variation across countries and over time. However, the ability of the term spread to forecast output growth has declined since the mid-1980s (Wheelock and Wohar, 2009). On the other hand, probit models show that the yield spread outperforms in relation to other macroeconomic and financial variables while predicting the probability of recession (Estrella and Hardouvelis, 1991; Estrella and Mishkin, 1998). The contemporaneous correlation between the yield spread and real GDP growth was found to be statistically insignificant for both the US and Germany (Table I.1.1). However, correlations between GDP growth and the yield spread lagged by one to six quarters were found to be positive and statistically significant for both the countries, except for the period t-1 for Germany, where it was found to be insignificant. These correlations suggest that the steeper is the yield curve – higher the yield on 10-year Treasury securities relative to that on 3-month Treasury securities – the higher is the future rate of GDP growth. Similarly, correlations between GDP growth and future yield spreads up to six quarters have been found to be negative and statistically significant for both countries, except for period t+1 where it is insignificant for both countries. Negative correlations between GDP growth and the lead terms of the yield spread suggest that higher the GDP growth in period t, less steep would be the yield curve in subsequent quarters (Sahoo and Gupta, 2019). To sum up, the yield spread has been useful in predicting output growth and recessions at least up to one year in advance, particularly in major AEs, although its signalling value has somewhat blurred in the present environment of unconventional monetary policies. The current phase of negative yield spreads warrants that policymakers remain vigilant. References: Benati, L. and C. Goodhart (2008), “Investigating Time-Variation in the Marginal Predictive Power of the Yield Spread”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 32(4), pp. 1236-72. Estrella, A. and G. A. Hardouvelis (1991), “The Term Structure as a Predictor of Real Economic Activity”, Journal of Finance, 46(2), pp. 555-76. Estrella, A. and F. S. Mishkin (1998), “Predicting U.S. Recessions: Financial Variables as Leading Indicators”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(1), pp. 45-61. Feroli, M. (2004), “Monetary Policy and the Information Content of the Yield Spread”, Topics in Macroeconomics, 4(1), Article 13. Harvey, C. R. (1988), “The Real Term Structure and Consumption Growth”, Journal of Financial Economics, 22(2), pp. 305-33. Sahoo, S. and B. Gupta (2019), ';Does Yield Spread Predict Output Growth?';, Reserve Bank of India (Mimeo). Wheelock, D. C. and M. E. Wohar (2009), “Can the Term Spread Predict Output Growth and Recessions? A Survey of the Literature”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, September/October. | (ii) International Crude Oil Prices The Indian basket of crude oil prices has exhibited high volatility in the first half of 2019-20 and the outlook remains uncertain. Upside risks to the baseline assumption can emanate from geo-political tensions. Assuming crude oil prices increase to US$ 73 per barrel, inflation could be higher by around 30 bps and growth weaker by around 20 bps from the baseline. Conversely, crude oil prices could soften further if global demand turns out to be weaker than expected. Should the price of the Indian basket of crude fall to US$ 53, inflation could ease by around 30 bps and growth could be higher by around 20 bps (Charts I.11a and I.12a). (iii) Exchange Rate The INR depreciated vis-à-vis the US dollar in August 2019, reflecting global developments. Looking ahead, rising trade protectionism, and slowing global trade and global output could increase volatility in international financial markets and exert further downward pressure on the currency. Should the INR depreciate by 5 per cent from the baseline, inflation could edge up by around 20 bps and boost net exports and GDP growth by around 15 bps. In contrast, a slew of measures taken by the government to boost output and investment, policy reforms in the FDI regime, and greater than expected monetary policy accommodation by the central banks in major AEs could attract increased capital inflows and lead to an appreciation of the INR. An appreciation of the INR by 5 per cent could moderate inflation by around 20 bps and GDP growth by around 15 bps vis-à-vis the baseline (Charts I.11b and I.12b). (iv) Food Prices Food prices picked up during April-August, mainly due to pressures from prices of vegetables and pulses. However, overall food inflation remains benign. The baseline path assumes that food inflation will firm up in the near term reflecting, inter alia, the seasonal pick-up in prices of vegetables and some pick-up in prices of pulses as the demand-supply balance stabilises. There are both upside and downside risks to the baseline. The strong revival of monsoon during July-September and the resultant catch-up in kharif sowing, large buffer stocks, and improved prospects for rabi crops from better reservoir levels could soften food inflation more than assumed, and consequently, headline inflation could be below the baseline by up to 50 bps. However, heavy rains and floods in some areas could exert some upward pressure on food inflation and accordingly, headline inflation could be higher by around 50 bps (Charts I.11b and I.12b). I.5 Conclusion Headline inflation is projected to remain below the medium-term target of 4 per cent over the rest of 2019-20 and the early months of 2020-21. Volatility in international and domestic financial markets, as well as global crude oil prices, and domestic prices of perishable food items pose upside risks to the baseline inflation path. On the other hand, the softer outlook on global commodity prices and large buffer stocks could keep headline inflation below the baseline. Real GDP growth is expected to recover in H2:2019- 20, facilitated by favourable base effects and transmission of past monetary policy actions. The measures announced by the government in August-September to boost growth – such as release of funds for recapitalisation of public sector banks, merger of public sector banks, reforms in the FDI regime, initiatives for exports and the real estate sector, reduction in the corporate income tax rate – and faster resolution of stressed assets could push growth above the baseline path. Intensification of global uncertainty around US-China trade tensions, a hard Brexit and geo-political tensions are key downside risks to the baseline growth path.

_________________________________________________________

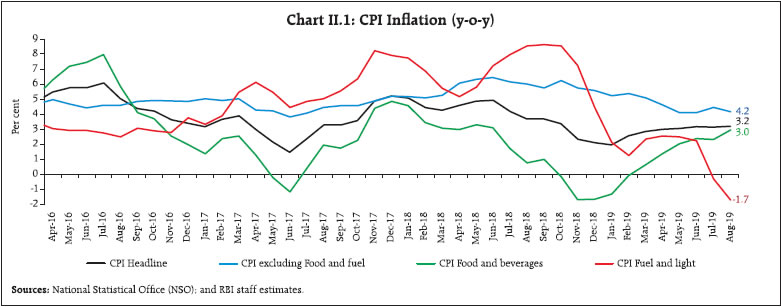

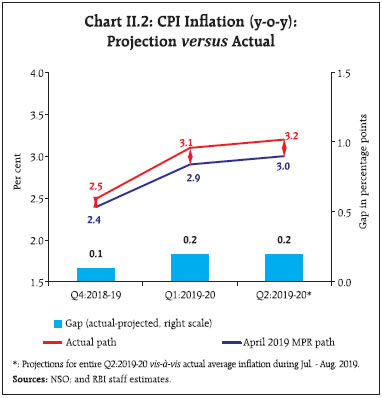

II. Prices and Costs Consumer price inflation registered an uptick during March-August 2019, underpinned by a pick-up in food inflation, particularly in vegetables and protein-based items. Fuel group inflation moderated sequentially after April and moved into deflation in July and August 2019. Inflation excluding food and fuel has softened since March in a broad-based manner notwithstanding a sharp increase in gold prices. Nominal growth in rural wages, both for agricultural and non-agricultural labourers, remained subdued. Growth in organised sector staff costs showed divergent movements – rising for the manufacturing sector and remaining range bound for the services sector. Farm inputs and industrial raw materials price inflation has softened in 2019-20 so far. Over the last six months i.e., March-August 2019 consumer price index (CPI) inflation trailed below the target of 4.0 per cent averaging 3.1 per cent over this period.1 Its key driver was food prices which emerged out of deflation in March 2019 and gradually firmed over the ensuing months in the usual summer season upturn. In contrast, prices of fuel and light items remained soft and slumped into deflation during July-August 2019. Excluding food and fuel, inflation ebbed by around 100 basis points between March- June 2019 and reached a 23-month low in June 2019, before registering some uptick during July-August (Chart II.1). The RBI Act, 1934 (amended in 2016) enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual outcomes from projections, if any, and to explain the underlying reasons thereof. The Monetary Policy Report (MPR) of April 2019 had projected CPI inflation at 2.9 per cent for Q1:2019-20 and 3.0 per cent for Q2:2019-20. Actual inflation outcomes have, by and large, tracked these projections (Chart II.2). While food prices moved out of deflation as anticipated, the summer rise in prices of vegetables this year was more pronounced than observed in recent history. Pulses prices moved out of two and a half years of deflation in May 2019. As a result, food inflation inched up by 230 basis points, larger than expected, between March and August 2019. Meanwhile, inflation excluding food and fuel softened more than anticipated, providing an offset. The Indian basket of crude oil prices eased unexpectedly – from an average of US$ 67 per barrel during 2019-20 (which was the baseline assumption in the April MPR) to below US$ 60 per barrel in August. Prices within the fuel group underwent substantial correction in respect of both rural items of consumption such as firewood and dung cake and those of urban usage such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Consequently, the fuel group as a whole slipped into deflation during July-August. On the whole, these divergent movements caused CPI headline inflation outcomes to marginally overshoot inflation projections, i.e., by 20 basis points each in Q1:2019-20 and Q2:2019-20 (July-August) (Chart II.2).

II.1 Consumer Prices A decomposition of year-on-year (y-o-y) inflation shows that its rising trajectory during March to June 2019 was propelled by a sustained increase in price momentum (Chart II.3). In July, large favourable base effect helped moderate the high price momentum.2 In August, however, the price momentum outweighed a low base effect and consequently, inflation edged up marginally. The elevation in price momentum in H1:2019-20 was driven by the food group, mainly by prices of vegetables, pulses, meat and fish. In contrast, the momentum underlying fuel and light inflation collapsed during July-August under the weight of a broad-based decline in prices of items of rural and urban fuel consumption. The momentum of prices of items excluding food and fuel moderated during March-August 2019 and was completely overwhelmed by favourable base effects, barring July. The distribution of inflation across CPI groups shows a considerable drop in median inflation rates – from 4.8 per cent in 2018 to 2.1 per cent in 2019 so far. Moreover, the negative skew in inflation in 2017 and 2018 resulting from food prices was absent in 2019, implying that a generalised moderation in inflation was underway this year (Chart II.4). Diffusion indices of month-on-month (m-o-m) price changes in CPI items on a seasonally adjusted basis moderated during June-August 2019 across both goods and services categories (Chart II.5).3

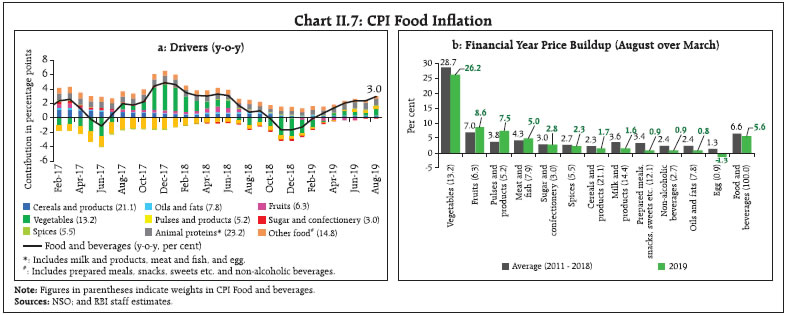

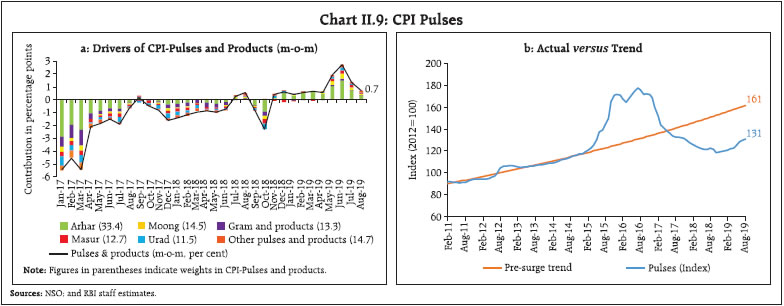

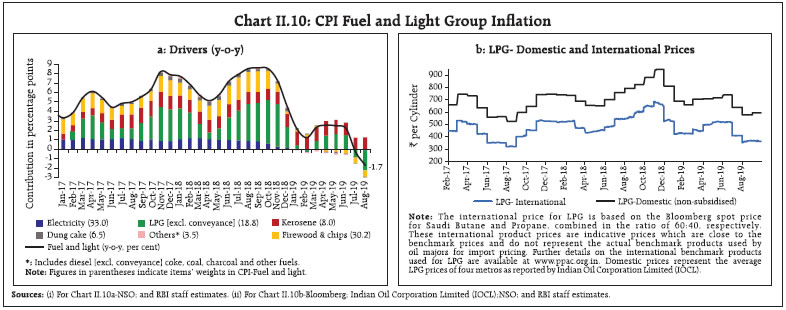

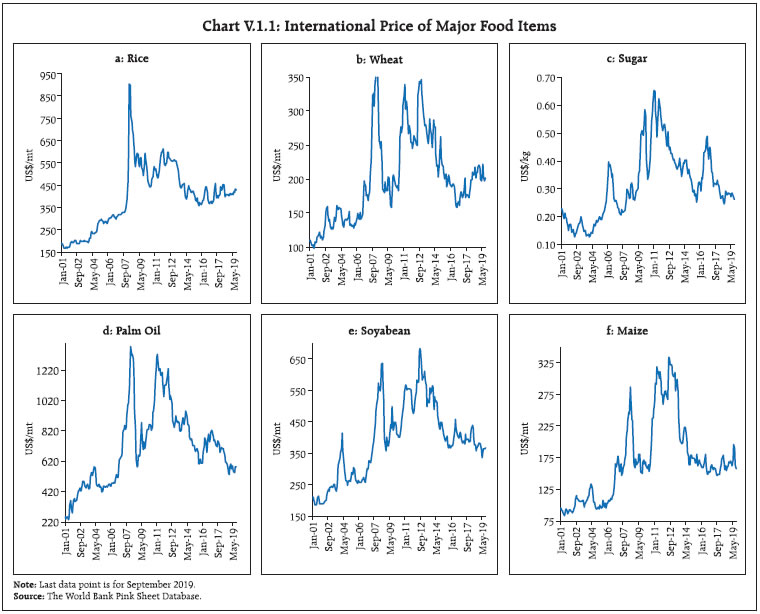

II.2 Drivers of Inflation A historical decomposition of inflation shows that it was impacted by positive supply shocks in H1:2019- 20, which, in conjunction with subdued domestic demand, kept headline inflation low and stable (Chart II.6a).4 The break-up of overall CPI inflation into goods and services components suggests that perishable goods (non-durable goods with 7-day recall) such as vegetables and fruits were the largest contributor to overall inflation during April-August (Chart II.6b). The contribution of less perishable goods (non-durable goods with 30-day recall) moderated due to deflation in prices of rice, petroleum products, LPG and electricity. The contribution of durable goods to overall inflation increased during June-August 2019, primarily on account of a sharp increase in prices of gold and to a lesser extent, in those of motor vehicles. Imported goods (petrol; diesel; LPG; kerosene; electronic goods; gold; silver; chemical and chemical products; metal and metal products; and refined vegetables oils) together contributed negatively to overall inflation in the recent period (Chart II.6c). The contribution of services to overall inflation moderated. However, services (with a weight of 23.4 per cent in overall CPI) contributed to about a third to overall inflation (Chart II.6b). CPI Food Group In terms of weighted contribution, the food and beverages group (weight: 45.9 per cent in CPI) contributed 32.9 per cent to overall inflation during April-August 2019 as compared with 25.0 per cent for the same period a year ago. Inflation in the food group turned positive beginning March 2019 – after remaining in the negative zone for five consecutive months during October 2018-February 2019 – and increased steadily thereafter driven by prices of vegetables, fruits and protein-rich items such as pulses, meat, fish and milk (Chart II.7a). Within the food and beverages group, the price build-up during the financial year so far in the case of vegetables has been substantial, but close to historical summer price increases. In the case of fruits, pulses, meat and fish, the price build-up has been, in fact, larger than the historical average (2011-18). For all the other sub-groups within the food group, the build-up has been much lower than in the past (Chart II.7b).  Inflation in respect of cereals (weight of 9.7 per cent in CPI and 21.1 per cent in the food and beverages group) remained moderate during April-August 2019, with rice prices remaining in deflation, reflecting robust production and adequate stocks. As per the fourth advance estimates of foodgrain production, production of rice was at 1164 lakh tonnes in 2018- 19, higher than 1128 lakh tonnes in 2017-18, which was until recently an all-time record. Exports of rice declined during April-July 2019 as the 5 per cent incentive provided by the government to rice exporters under the Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) was withdrawn from April 1, 2019 and this resulted in higher domestic availability. Wheat inflation, however, remained high at an average of 6.8 per cent during April-August 2019 (3.4 per cent in 2018-19) due to a fall in imports following a hike in import duty to 40.0 per cent in April 2019 from 30.0 per cent in May 2018. As regards vegetables (weight of 6.0 per cent in CPI and 13.2 per cent in the food and beverages group), a recovery in the prices of onions, tomatoes and potatoes (which account for 36.5 per cent of the total CPI vegetables) led the upturn in prices (Chart II.8a). Potato price pressures picked up right from April 2019. First, untimely rains during February and March in West Bengal impacted the crop which was ready to be harvested. Second, mandi arrivals declined due to a sudden increase in temperature during summer months and thunderstorms in several parts of northern and north-eastern states that spoiled the produce in transit. Despite this firming up, potato prices moved into deflation beginning April 2019 on account of favourable base effects. Onion prices, which had declined during December 2018-March 2019, revived from April with a sharp uptick during June-August. A reduction in rabi onion acreage in Maharashtra, particularly in the major onion-producing district of Nashik due to drought-like conditions, led to a slump in mandi arrivals. Onion prices were also supported by procurement operations by the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) in Maharashtra. Excessive rainfall, coupled with floods in several parts of major onion-supplying states such as Maharashtra, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh during July-August, also led to a reduction in supplies. Tomato prices began picking up from March 2019, with inflation in this item rising sharply to 70.1 per cent in May 2019 from (-) 52.2 per cent in November 2018. Delayed harvesting in Maharashtra as well as fungus damaged crops in Karnataka triggered the initial uptick in prices, which was exacerbated by supply disruptions due to incessant rains and floodlike situations in key supplier states – Karnataka, Maharashtra and Himachal Pradesh. Tomato inflation, however, eased to 28.4 per cent in July largely due to a favourable base effect, before hardening to 39.4 per cent in August on account of an adverse base effect.  A decomposition of CPI vegetables into trend, cyclical and seasonal components reveals that the cyclical upswing, starting from December 2018, was the key driver of the vegetables inflation during H1:2019-20 (till July 2019), with the trend component remaining flat. The seasonal uptick during the summer season tracked the pattern in previous years (Chart II.8b). Prices of fruits (weight of 2.9 per cent in CPI and 6.3 per cent within the food and beverages group) moved into deflation in December 2018. Fruits prices began rising from February 2019 with sharp uptick in April and July. However, fruits remained in deflation up to August 2019. Price pressures were particularly evident in respect of bananas and apples, which together constitute around 35.6 per cent of the category of fruits. While banana prices were impacted by lower mandi arrivals, apple prices increased in the usual seasonal upturn. Apple prices were also supported by lower imports following the increase in import duty on apples from the US by 20.0 per cent in June 2019. However, price pressures in respect of both bananas and apples declined in August due to higher domestic arrivals in mandis. The rise in prices of vegetables and fruits during the summer months of 2019 was witnessed in urban as well as rural areas. A sectoral analysis suggests that there is no statistically significant difference between the m-o-m changes in prices of fruits and vegetables between rural and urban areas. There is, however, statistically significant higher volatility in m-o-m changes in prices of vegetables and fruits in urban areas than in rural areas5. CPI pulses (weight of 2.4 per cent in CPI and 5.2 per cent in the food and beverages group), driven by a sustained uptick in prices, emerged from 29 successive months of deflation in May 2019 to reach a 35-month high inflation of 6.9 per cent in August 2019 (Chart II.9a). Even so, the CPI pulses index remained below trend (Chart II.9b). Pulses production was lower at 234 lakh tonnes (as per the fourth advance estimates) in 2018-19 than 254 lakh tonnes in 2017-18. In addition, pulses imports declined from 57 lakh tonnes in 2017- 18 to 26 lakh tonnes in 2018-19, reducing the domestic supply glut. A sizeable stock of pulses – at around 40 lakh tonnes – is available, which could be released in the market to contain price pressures. Meat and fish prices also contributed to the pick-up in food inflation, partly reflecting the sustained rise in feed prices, particularly of maize. In fact, inflation in meat and fish prices was the highest in 62 months in July 2019. While egg prices moved in line with their historical pattern, those of milk and products hardened during May-August 2019, primarily reflecting an increase in retail milk prices by ?2 per litre to ?6 per litre due to pass-through of an increase in procurement prices of milk by ?5-6 per litre by milk co-operatives.  Prices of sugar emerged out of deflation in May 2019 after remaining in negative territory for 15 consecutive months. However, they slipped back into deflation during June-August 2019, reflecting domestic supply surpluses as well as favourable base effects. As per the Indian Sugar Mills Association (ISMA), the opening stock of sugar as on October 1, 2019 is expected to be at an all-time high of 145 lakh tonnes. International sugar prices, which were in deflation during May 2017-February 2019 due to persistent excess global supply, also returned to positive territory in March 2019. Some increase in sugar prices in the domestic market was observed in Q1:2019-20, possibly reflecting the increase in minimum selling prices of sugar by ?2 per kilogram in February 2019. Inflation in respect of oils and fats remained subdued at around 0.8 per cent during April-August 2019, with soft international prices and higher domestic production keeping prices under check. According to the fourth advance estimates, oilseeds production increased by 2.5 per cent in 2018-19; however, a decline in groundnut production during the year contributed to price pressures in groundnut oil during a major part of 2018-19 as well as in 2019-20 so far. CPI Fuel Group Fuel group inflation moderated sequentially after April up to June and sank into deflation in July and August 2019, with inflation in major constituents such as electricity, LPG, firewood and chips and dung cake all slipping into negative territory (Chart II.10a).

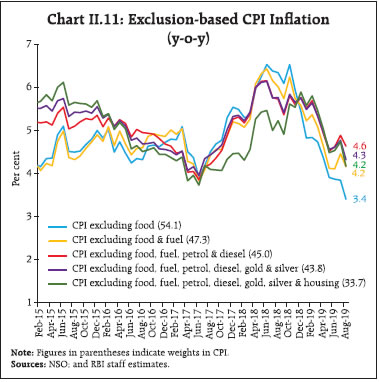

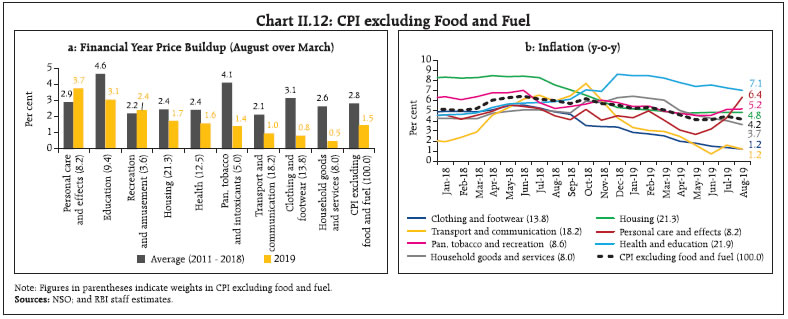

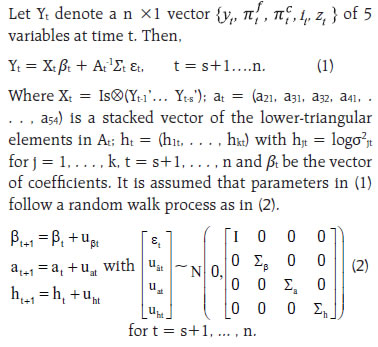

After registering price increases between March- June, domestic LPG prices declined abruptly in July and August, following a collapse in international petroleum products prices (Chart II.10b). Electricity prices, which constitute around one-third of the fuel and light sub-group, have been in deflation for most of the months since January 2019. Prices of items of rural consumption such as firewood and chips, and dung cake have also remained in deflation since April 2019. This could partly be on account of increased LPG use in rural areas.6 In contrast, administered kerosene prices registered calibrated increases as oil marketing companies (OMCs) raised administered prices to align them more closely with market prices so as to eventually phase out the subsidy on petroleum products. CPI excluding Food and Fuel CPI inflation excluding food and fuel moderated by close to 100 bps between March and June 2019. Even excluding volatile components such as petroleum products, gold and silver, it moderated by around 70 bps, reflecting the broad-based nature of the disinflation in this group. Although inflation excluding food and fuel picked up by 35 bps in July 2019, it was not sustained and it moderated by about 30 bps in August (Chart II.11). Within CPI excluding food and fuel, price increases during the financial year so far have been considerably lower than historical averages for most of the constituent sub-groups (Chart II.12). Empirical evidence suggests that persistently low food inflation has spilled over to CPI excluding food and fuel (Box II.1).

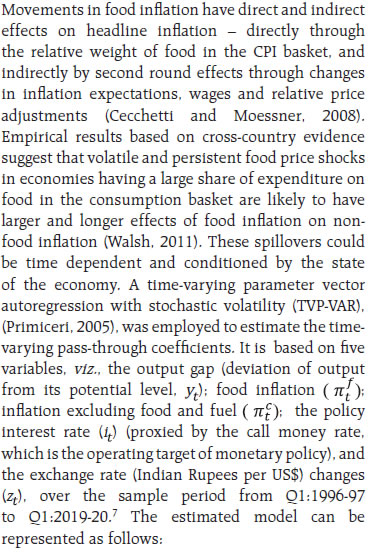

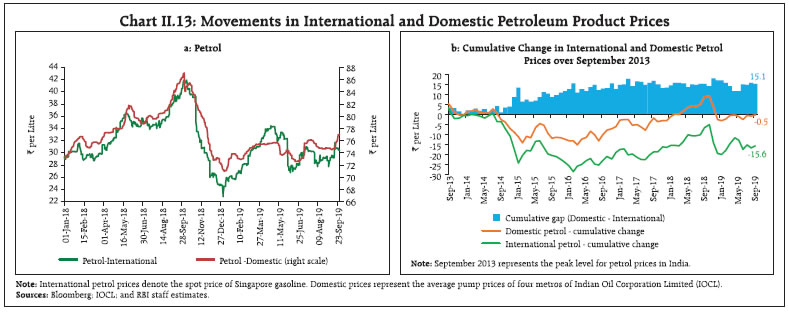

Box: II.1: Time-varying Estimates of Spillovers from Food Inflation to Inflation excluding Food and Fuel

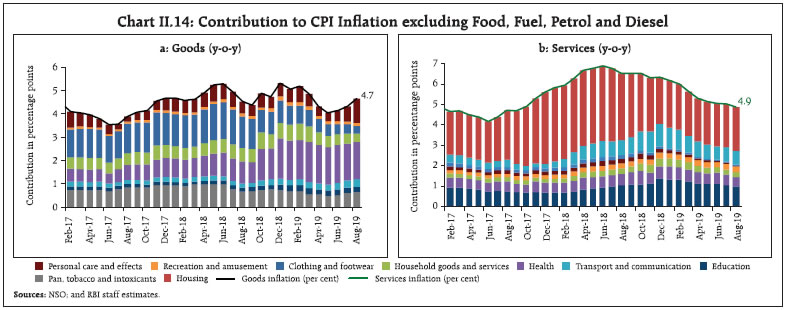

The empirical results suggest that (i) pass-through coefficients are time varying – ranging between 8 per cent and 14 per cent during Q3:2003-04 to Q1:2019- 20; (ii) pass-through is high when food inflation is high and persistent, and low when food inflation is low. In the recent low food inflation scenario, the pass-through coefficient has moderated to around 10 per cent (Chart II.1.1a & b). In view of this asymmetric impact of food inflation on inflation excluding food and fuel, maintaining low and stable food prices becomes critical to contain underlying inflation pressures. This would entail supply side reforms to ensure that food inflation remains under check. Reference Bordoloi, S. (2019), “Spill-over from Food inflation to Core inflation in India: An Empirical Analysis”, (Mimeo). Cecchetti, S. and Moessner, R. (2008), ‘Commodity prices and inflation dynamics’, Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review, Bank for International Settlements, pp. 55–66. Reserve Bank of India (2014), ‘Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (Chairman: Dr Urjit R. Patel)’. Primiceri, G. (2005), ‘Time Varying Structural Vector Autoregressions and Monetary Policy’, Review of Economic Studies, 72, pp. 821-852. Walsh, J. (2011), ‘Reconsidering the role of food prices in inflation’, IMF Working Paper, WP/11/71, International Monetary Fund. | Inflation in the transport and communication sub-group moderated primarily due to a sustained deflation in petroleum product prices (Chart II.13a). However, the wedge between international and domestic prices remains considerable due to an incomplete passthrough (Chart II.13b). An examination of the components of CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol and diesel inflation in terms of goods and services shows that while goods inflation saw phases of both moderation (February-May) and uptick (June-August), services inflation has fallen persistently (Chart II.14a & b). A key sub-group contributing to the downturn in goods inflation was clothing and footwear, mainly in rural areas. Other sub-groups contributing to the goods moderation were personal care items, particularly, gold; silver; and toiletries, and household goods and services items. The pick-up in goods inflation since June has almost entirely emanated from the personal care and effects sub-group, driven by a sharp pick-up in gold prices. Services inflation moderated from elevated levels in February 2019 to 4.9 per cent in August 2019 (Chart II.14b) in a broad-based manner across education services like tuition and coaching; transportation fares, particularly, bus fares; medical services; housing; and household services like sweeping and tailoring charges.

Other Measures of Inflation Inflation in sectoral CPIs, i.e., for industrial workers (CPI-IW), agricultural labourers (CPI-AL) and rural labourers (CPI-RL), rose rapidly between March and June 2019 compared with the muted uptick in CPI headline inflation. Inflation in food and fuel components of CPI-AL and CPI-RL was higher than that in headline CPI and was accentuated by the larger share of food in these indices. In the case of CPI-IW, a major source of divergence was the housing component. Following the increase in HRA under the 7th central pay commission (CPC), housing inflation in CPI-IW remained above 26 per cent during July 2018 to June 2019, pushing CPI-IW inflation to 8.7 per cent by May 2019. As the effect of increase in HRA waned, CPI-IW inflation declined to 6.3 per cent in August. Inflation in wholesale price index (WPI) fell steadily in contrast to the sectoral CPIs to a low of 1.1 per cent in August 2019. On the one hand, fuel group inflation collapsed from 4.6 per cent in March to (-) 4.0 per cent in August 2019 tracking international petroleum product prices; inflation in non-food manufactured products also fell across the board and was in contraction in August. On the other hand, WPI food inflation showed an uptick from January and remained elevated till August, barring a fleeting correction in July. GDP and GVA deflators broadly remained in alignment with CPI inflation during the last six months (Chart II.15a). Underlying inflation dynamics can be gauged from exclusion-based measures that remove volatile items/item groups or by statistical measures such as trimming, which adjust for positive and negative skewness and chronic fat tails in the inflation distribution by removing outliers. By these measures, inflation have moved with a softening bias over the last six months (Chart II.11 & 15b). II.3 Costs Developments in underlying cost conditions have largely been in sync with inflation in terms of the WPI (Chart II.16). Price inflation in farm inputs and industrial raw materials (extracted from the WPI) has fallen in 2019-20 so far. The moderation in global crude oil prices during 2019-20 has kept domestic price pressures under check in respect of inputs such as high-speed diesel, aviation turbine fuel, naphtha, furnace oil and petroleum coke. In addition, the contraction in mineral prices has also aided the fall in industrial input costs. Among other industrial raw materials, domestic coal inflation has subsided significantly since the beginning of 2019-20, averaging around 0.7 per cent during April-August 2019. Domestic coal prices largely moved in line with international coal prices during the period. Inflation in paper and paper products has also moderated due to lower raw material costs including those of pulp and coal. In the case of fibres, inflation eased during June-August 2019, predominantly reflecting the easing in prices of raw jute and raw cotton. Of farm sector inputs, price pressures in respect of fertilisers remained subdued, largely reflecting moderation in international prices, especially those of phosphate, di-ammonium phosphate and triple superphosphate. Inflation in respect of pesticides and other agrochemical products also softened considerably in Q1:2019-20 due to easing of international crude oil prices. The price of electricity, which carries a high weight in both industrial and farm inputs, moved into deflation during June-August 2019. However, inflation in fodder prices turned positive in January 2019, after remaining in deflation during August 2016-December 2018 (barring August 2017), to touch a 37-month high of 16 per cent in July 2019, before easing somewhat in August. Inflation in terms of agricultural machinery and implements costs has also remained elevated and sticky from H2:2018-19. Growth in nominal rural wages, both for agricultural and non-agricultural labourers, remained subdued and sticky, hovering around 3.7 per cent and 3.8 per cent, respectively, during 2019-20 so far, reflecting the lagged impact of moderate rural inflation, low food prices and a slowdown in the construction sector (Chart II.17).

With inflation in CPI-AL and CPI-RL having picked up since February 2019, however, real rural wage growth, based on these price indices, turned negative since March 2019. Growth in organised sector staff costs showed divergent movements for services and manufacturing firms. Unit labour costs for companies in the manufacturing sector fell marginally in Q4:2018-19 but rose thereafter in Q1:2019-20 to 6.3 per cent due to a decline in the value of production, coupled with increase in staff cost.8 Unit labour cost for firms in the services sector increased marginally in the last quarter as higher growth in staff costs outpaced the growth in value of production (Chart II.18). Manufacturing firms participating in the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey reported a fall in input costs in Q2:2019-20 on account of lower raw material costs. The cost of finance and salary outgoes are also expected to soften in Q2. The fall in input prices is likely to translate into a fall in selling prices in Q2. Firms polled for the manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) reported a decline in input costs and selling prices sequentially from Q2:2018-19 to Q1:2019-20. However, the rate of decline in selling prices in Q1:2019-20 was sharper than that of input costs. During Q2:2019-20, both input costs and selling prices firmed up. Input cost inflation reported by firms in the services sector PMI also softened gradually from Q2:2018-19 to Q1:2019-20 but increased during the first two months of Q2:2019-20. II.4 Conclusion The inflation trajectory in 2019-20 so far has been characterised by rising food inflation, with price build-ups close to historical averages and well above levels observed in recent years, driven largely by a strong summer pick-up in prices of vegetables. Going forward, however, the build-up in vegetables prices is likely to reverse with arrivals of the kharif harvest and winter supplies. The catch-up in monsoon and sowing should help mitigate price pressures in cereals. Moreover, buffer stocks of cereals are well above prescribed norms. In the case of pulses, the arrival of fresh produce in the market along with buffer stocks are also likely to keep prices under check. Going forward, domestic fuel and petroleum product prices are subject to considerable uncertainty due to geopolitical developments in the Middle East. A sudden spike in crude oil and petroleum products prices remains a major upside risk in spite of weak global demand. However, given the weak domestic demand and lower input costs, inflation in CPI excluding food and fuel is likely to remain moderate. Forward looking surveys of the Reserve Bank point to weak consumer confidence and sagging demand, especially pertaining to non-essential items. Manufacturing firms see input prices as still soft and pricing power is yet to firm up as the cost of finance and salary outgoes remain muted. However, inflation expectations of households have risen somewhat. On the whole, headline CPI inflation is expected to remain within the Reserve Bank’s target of 4.0 per cent during 2019-20. _________________________________________________________

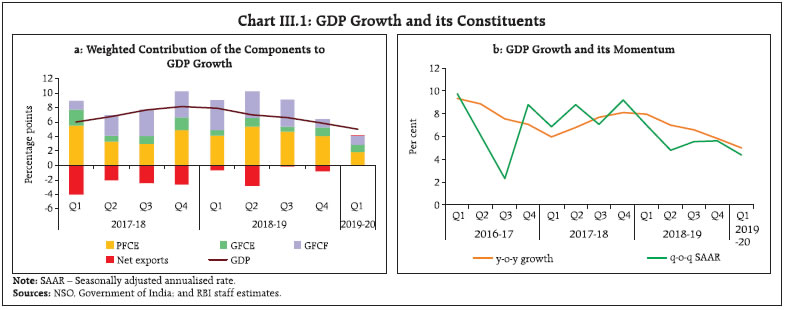

III. Demand and Output Aggregate demand weakened in Q1, underpinned by a slowdown in private consumption. On the supply side, a sharp deceleration in manufacturing essentially reflected weaknesses in the organised sector. Services sector growth was pulled down by ‘financial, real estate and professional services’ and construction activity. The recent measures by the Government should help kickstart the capex cycle and lead to the strengthening of domestic demand. Domestic economic activity suffered a sharp loss of pace in Q1:2019-20. Aggregate demand weakened in Q1:2019-20 by a slowdown in private consumption. On the supply side, manufacturing activity collapsed with the prolonged slowdown in the production of capital goods and consumer durables and in the services sector, construction activity slowed down markedly. Incoming data suggest that the slowdown persisted into Q2:2019-20. III.1 Aggregate Demand Measured by year-on-year (y-o-y) changes in real gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices, the deceleration in aggregate demand in Q4:2018-19 deepened to 5.0 per cent in Q1:2019-20, extending the sequential slowdown that set in during Q1:2018- 19 to the fifth consecutive quarter (Table III.1 and Chart III.1a). Momentum, measured by quarter-onquarter (q-o-q) seasonally adjusted annualised GDP growth rate (SAAR), also moderated to 4.4 per cent in Q1:2019-20 from 5.6 per cent in Q4:2018-19 (Chart III.1b). Of the constituents of GDP, private final consumption expenditure (PFCE), the mainstay of aggregate demand, slumped, with its growth plummeting by over four percentage points in Q1:2019-20 to an eighteen-quarter low. Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) cushioned the deceleration in aggregate demand. Excluding GFCE, real GDP growth would have slid down to 4.5 per cent in Q1:2019- 20. Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) remained weak in Q1:2019-20, with the capex cycle yet to gain traction. Export growth decelerated considerably in Q1:2019-20 in an uncertain external trading environment rendered hostile by trade tensions. With import growth reflecting domestic demand conditions and slowing more sharply, net exports made a positive contribution to growth after a gap of nine quarters. | Table III.1: Real GDP Growth (Per cent) | | Item | 2017-18 (FRE) | 2018-19 (PE) | Weighted Contribution* | 2017-18 (FRE) | 2018-19 (PE) | 2019-20 | | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | | Private final consumption expenditure | 7.4 | 8.1 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 10.1 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 3.1 | | Government final consumption expenditure | 15.0 | 9.2 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 21.9 | 7.6 | 10.8 | 21.1 | 6.6 | 10.9 | 6.5 | 13.1 | 8.8 | | Gross fixed capital formation | 9.3 | 10.0 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 9.3 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 3.6 | 4.0 | | Exports | 4.7 | 12.5 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 10.2 | 12.7 | 16.7 | 10.6 | 5.7 | | Imports | 17.6 | 15.4 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 23.9 | 15.0 | 15.8 | 16.2 | 11.0 | 22.9 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 4.2 | | GDP at Market Prices | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 5.0 | FRE: First Revised Estimates; PE: Provisional Estimates.

*: Component-wise contributions to growth do not add up to GDP growth in the table because change in stocks, valuables and discrepancies are not included.

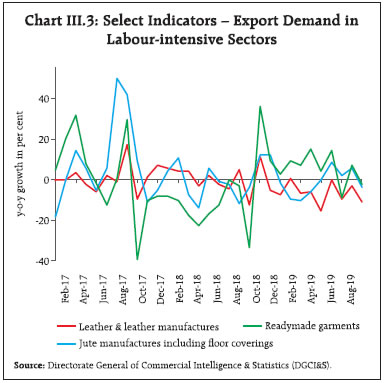

Source: National Statistical Office (NSO), Government of India. | GDP Projections versus Actual Outcome The April 2019 MPR had projected real GDP growth of 6.8 per cent for Q1:2019-20, with risks evenly balanced around the baseline path (Chart III.2). The actual outcome for the quarter undershot the projections by 180 basis points. First, the realised growth in private consumption demand surprised significantly on the downside, indicating that the April 2019 projection underestimated the broad-based slowdown in both rural and urban consumption. Second, GFCF growth also turned out lower than the projection on account of lower than expected capital goods production and their imports, and moribund activity in construction. III.1.1 Private Final Consumption Expenditure The unexpected slump in PFCE resulted in its share falling to 55.1 per cent in Q1:2019-20 from 56.1 per cent a year ago. The slowdown in private consumption was amplified by weak growth in some of the labour intensive export sectors such as readymade garments, leather manufactures and jute manufactures (Chart III.3).

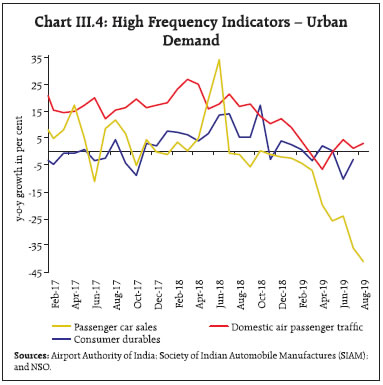

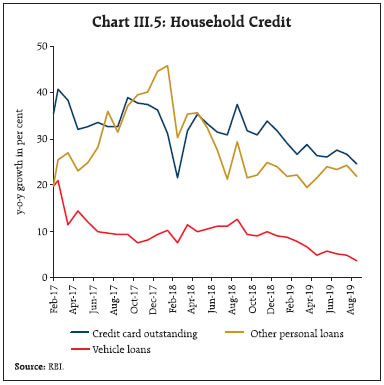

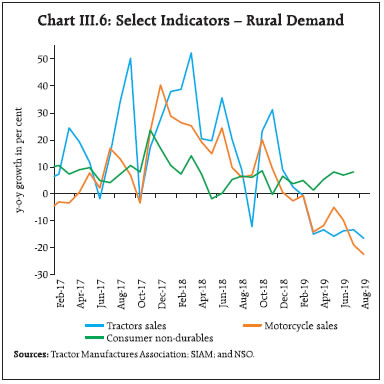

High frequency indicators of urban demand have weakened in recent months as reflected in contraction in sales of passenger vehicles and production of consumer durables (Chart III.4). Among them, passenger car sales have contracted by double digits every month since April 2019, resulting in major car producers suspending factory production intermittently. A combination of factors such as higher prices due to stricter safety norms, uncertainty caused by new emission norms and the proposed switching to electric vehicles have dented the sales of passenger vehicles (Box III.1). The growth in household credit for vehicles extended by banks also moderated (Chart III.5). Domestic air passenger traffic growth remained modest in July due to grounding of a private airline, which impacted air fares and dampened demand; however, it improved in August. Going forward, passenger vehicle sales could improve with the government’s recent support for the sector such as permitting the operation of Bharat Stage (BS)-IV vehicles purchased till March 31, 2020, for the entire period of registration; withdrawal of a ban on the purchase of new vehicles by government departments; and deferring the implementation of hike in the one-time registration fee until June 2020. Various indicators of rural demand have also remained weak (Chart III.6). Motorcycles and tractor sales contracted in July and August. Although the growth of consumer non-durables accelerated in July, it was driven mainly by sunflower oil. The sales growth of fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies, a sizeable part of which occurs in rural areas, has also been sluggish. The reasonably strong kharif foodgrains production in the first advance estimates of the Ministry of Agriculture – only 0.8 per cent below last year’s level – and bright prospects for the rabi season in view of soil moisture conditions and comfortable reservoir levels could buoy rural incomes and demand, going forward.

Box III.1: Slowdown in the Automobile Sector The downturn in the automobile sector in India, which could be attributed to several regulatory and institutional factors, was accentuated by a slowdown in demand. This has drawn considerable attention in view of the industry’s role in economic activity1. An estimation framework using vector auto regressions with exogenous variables (Ludvigson, 1998) (VARX) was conducted to assess the underlying factors for the slump in the auto sector using quarterly data from Q1:2007-08 to Q1:2019- 20. In the first VARX (1): Y = A(L)Y + CX + U, ....(1) where Y = [ct, yt, st, it] is a vector of variables endogenous to the simultaneous system of equations. ct is the credit demand measured as a gap between the credit disbursed by scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) for automobile purchases from its long-term trend. st is the deviation of sales of commercial vehicles from its long-term trend. yt is aggregate demand measured as the output gap and it is the weighted average lending rate of SCBs. A rise in aggregate demand and credit demand are expected to increase vehicle sales. On the other hand, an increase in interest rate is expected to moderate auto sales. X = [zt, pt, d1, d2] is a vector of exogenous variables determined from outside the simultaneous system of equations, zt is the y-o-y change in INR/US$ exchange rate, pt is the y-o-y change in diesel prices, d1 is a dummy variable representing the implementation of BS-IV from April 2017. d2 is a dummy variable representing three events which happened during the second half of 2018-19, viz., liquidity issues faced by non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) post-IL&FS default, the announcement of axle load norms and implementation of insurance and safety norms. Ut is a vector of idiosyncratic errors. A similar model was estimated by using the deviation of sales of passenger cars from its long-term trend instead of sales of commercial vehicles (st) in (1). The key findings emerging from the impulse response functions (IRFs) from the two VARXs (Charts III.I.1) are:

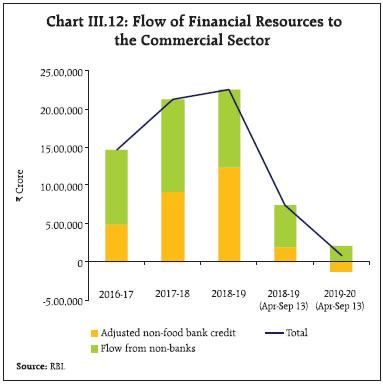

(i) both commercial vehicle and passenger car sales are sensitive to aggregate demand shocks; (ii) both commercial vehicle and passenger car sales respond positively to a decline in interest rates; (iii) fuel prices have a negative impact on commercial vehicle sales; (iv) exchange rate depreciation affects auto sales negatively; and (v) bank credit does not have any significant impact on vehicle sales; however, the reverse causation is statistically significant, i.e., sales of commercial vehicles positively impact bank credit flow to the automobile sector. The dummy, representing three events (d2) is statistically significant and explains 10 percentage points of the decline in commercial vehicle sales and 8 percentage points of the decline in passenger car sales. Shocks like the slump in demand, liquidity crisis in the NBFC sector and measures to enhance safety and security norms, appear to have resulted in a downswing in the automobile sector. A slowdown in passenger car sales was also observed in the US, the Euro area, China, South Korea and Japan for a variety of reasons (Chart III.1.2). These are: (i) stricter emission norms in China and the Euro area; (ii) mandatory sales of electric vehicles by car makers in the Euro area; (iii) tepid demand due to subdued global growth; and (iv) depressed consumer confidence from escalating US-China trade tensions. Reference: Ludvigson, S. (1998). “The Channel of Monetary Transmission to Demand: Evidence from the Market for Automobile Credit”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 30(3), pp. 365–383. | III.1.2 Gross Fixed Capital Formation Growth in gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) moderated sharply in Q4:2018-19 and Q1:2019-20 after double digit growth in the five previous quarters. The share of GFCF in aggregate demand declined to 32.5 per cent in Q1:2019-20 from 32.8 per cent a year ago. High frequency indicators suggest that investment activity remained sluggish in Q2. Import of capital goods and production of capital goods contracted in July (Chart III.7). However, housing loans disbursed by scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) remained resilient, reflecting the policy push for the affordable housing sector. Capacity utilisation (CU) in the manufacturing sector, measured by the order books, inventory and capacity utilisation survey (OBICUS) of the Reserve Bank, moderated to 73.6 per cent in Q1:2019-20 from 76.1 per cent in Q4:2018-19; seasonally adjusted CU, however, improved to 74.8 per cent in Q1:2019-20 from 74.5 per cent in Q4 (Chart III.8). The number of stalled projects in the private sector declined in Q1:2019-20, while there was some deterioration in stalled projects in the government sector in Q1 (Chart III.9). Gross capital formation has decelerated since 2011-12 due to a slowdown in investment by the private sector (Chart III.10). Underlying the latter is corporate deleveraging in select industries as reflected in improving interest coverage ratios (Chart III.11). The slowdown in investment activity was also reflected in a decline in financial flows from banks and non-banks to the commercial sector (Chart III.12; see Chapter IV for details).

III.1.3 Government Expenditure Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) cushioned aggregate demand in Q4:2018-19 and Q1:2019-20, as pointed out earlier. During April-August 2019, the fiscal position of the central government strengthened as the gross fiscal deficit (GFD) and revenue deficit (RD) improved vis-à-vis the corresponding period of the previous year in terms of budget estimates (BE), mainly due to lower growth in expenditure (Table III.2). Total expenditure of the central government in the current fiscal year so far has been driven by revenue expenditure.  | Table III.2: Key Fiscal Indicators – Central Government (April-Aug) | | (Per cent) | | Indicator | As a per cent of BE | y-o-y Growth | | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2019-20 | | 1. Revenue receipts | 26.9 | 30.7 | 29.8 | | a. Tax revenue (Net) | 24.7 | 24.5 | 10.5 | | b. Non-tax revenue | 40.1 | 63.4 | 102.0 | | 2. Total non-debt receipts | 26.4 | 29.8 | 29.6 | | 3. Revenue expenditure | 43.8 | 42.5 | 10.7 | | 4. Capital expenditure | 44.0 | 40.2 | 3.0 | | 5. Total expenditure | 43.8 | 42.2 | 9.8 | | 6. Gross fiscal deficit | 94.7 | 78.7 | -6.3 | | 7. Revenue deficit | 114.0 | 89.9 | -8.1 | | 8. Primary deficit | 767.7 | 773.4 | -10.0 | BE: Budget Estimates.

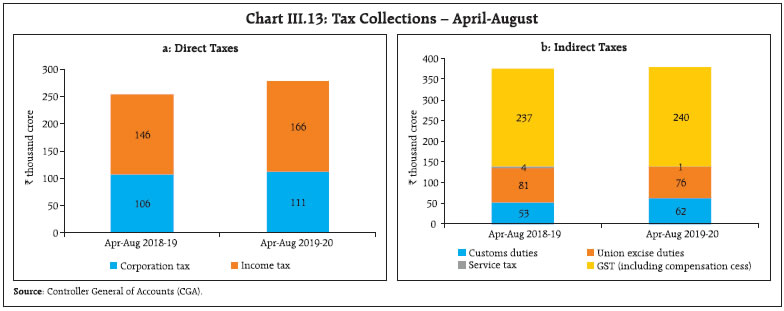

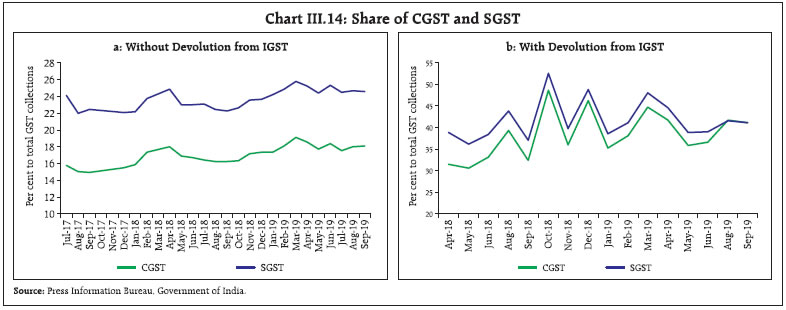

Sources: Controller General of Accounts; and Union Budget Document, 2019-20. | In order to meet expenditure commitments, revenue generation is critical. On the receipts side, income tax collections gained traction during April-August 2019 (Chart III.13). Notwithstanding month-over-month fluctuations, the GST collections grew by 4.9 per cent (y-o-y) during April-September 2019. The share of State GST (SGST) collections in total GST revenue has been sizably higher than Central GST (CGST), attributable to the adjustment for input tax credit. After apportionment of integrated GST (IGST) collections, the share of CGST collections remained significantly lower than SGST collections during April-September 2018. They did move closer subsequently, before finally catching up in August 2019 (Chart III.14a and 14b). There have, however, been large inter-state variations in SGST collections, with a few states not requiring the GST compensation cess. Plugging loopholes and mitigating information technology (IT) glitches such as putting in place an invoice-matching system to facilitate a system validated input tax credit, overcoming operational deficiencies of the payment module, alignment of system validations with the GST Acts and Rules along with alleviating system design deficiencies may facilitate tapping of GST potential.2

Non-tax revenue has been an important source of finance for the central government. During April- August 2019, this component witnessed robust growth driven by the surplus transfer from the Reserve Bank. Resource mobilising efforts through disinvestment may also help garner revenues, going forward. On the expenditure front, both revenue and capital expenditure of the central government witnessed some moderation in Q1:2019-20. However, after the declaration of election results, both revenue and capital expenditure picked up significantly during July-August 2019; almost 40 per cent of budgeted capital expenditure for roads and highways was incurred in the month of July 2019. Likewise, information available for 22 states indicates a slowdown in revenue expenditure in Q1:2019-20 though it picked up in July 2019. States have reduced their capital spending in order to adhere to fiscal deficit targets in the last few years (Chart III.15). This seems to have, in turn, affected investment adversely. Going forward, a pick-up in capital spending by both the centre and states is desirable given the growth augmenting property of the capital expenditure multiplier (RBI, 2019).3 A major challenge for government finances in the remaining period of the current financial year is to adhere to the budgeted capital spending and revenue generation targets. As regards direct taxes of states, stamp duty collections are highly correlated with construction activity (Chart III.16). Hence, a slowdown in the construction sector might impact stamp duty collections.

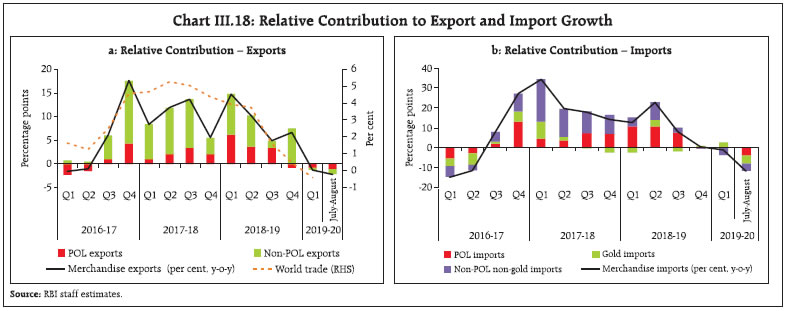

After remaining above 6 per cent of GDP between 2008-09 to 2016-17, the combined GFD of the centre and states dropped below 6 per cent in 2017-18. It is estimated at 6.2 per cent in 2018-19 (RE) and 5.9 per cent in 2019-20 (BE). Outstanding liabilities of the general government are budgeted to marginally decline to 69.6 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 from 69.8 per cent in 2018-19, driven by the centre, though states’ debt is showing a rising trend. The debt servicing capacity of the general government has improved in 2018-19 with the interest payments as per cent to revenue receipts exhibiting a decline. The Reserve Bank has managed the centre’s market borrowing programme during 2019-20 so far as per the planned issuance schedule. The budgeted gross market borrowing of the central government for 2019-20 at ?7,10,000 crore is about 24.3 per cent higher than last year. The central government completed 62.3 per cent of its budgeted gross market borrowings as on September 30, 2019 (50.4 per cent in the corresponding period of 2018-19) (Table III.3). The Union Budget 2019-20 provides for consolidation measures like switching of securities budgeted at ?50,000 crore, of which ?40,109 crore worth of securities have already been switched. The states completed 35.6 per cent of their budgeted gross market borrowings till September 30, 2019 as compared with 27.6 per cent in the corresponding period of 2018-19. A major part of market borrowings by the states is expected to occur in H2:2019-20. | Table III.3: Government Market Borrowings | | (? crore) | | Item | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 (September 30, 2019) | | Centre | States | Total | Centre | States | Total | Centre | States | Total | | Net borrowings | 4,48,410 | 3,40,281 | 7,88,691 | 4,22,737 | 3,48,643 | 7,71,380 | 3,40,972 | 1,56,447 | 4,97,419 | | Gross borrowings | 5,88,000 | 4,19,100 | 10,07,100 | 5,71,000 | 4,78,323 | 10,49,323 | 4,42,000 | 2,25,445 | 6,67,445 | III.1.4 External Demand Net exports contributed positively to aggregate demand in Q1:2019-20 for the first time after Q2:2016-17, as slowdown in import growth was more pronounced than that for exports. The persisting loss of momentum in global trade impacted India’s merchandise exports, which contracted during Q1:2019-20 and in July-August 2019-20 in both the petroleum, oil and lubricants (POL) and non-POL categories (Chart III.17a). The sectors which contributed to the overall decline included engineering goods, gems and jewellery and rice. POL exports declined mainly on account of a fall in international crude oil prices. In addition, routine maintenance-related shutdowns in major refineries adversely impacted exports in June 2019 (Chart III.18a). Imports also contracted in Q1:2019-20 due to deceleration in POL growth and decline in non-POL non-gold imports. Gold imports surged on the back of a decline in prices, wedding and festive season demand during Q1:2019-20 (Chart III.18b). The decline in non- POL non-gold imports was broad-based as imports of transport equipment, pearls and precious stones, metalliferous ores and vegetable oil contracted. Imports continued to contract in July-August 2019 in a broad-based manner. The trade deficit moderated from US$ 46.7 billion in Q1:2018-19 to US$ 46.2 billion in Q1:2019-20, although on a sequential basis, i.e., Q1:2019-20 over Q4:2018-19, it expanded modestly. However, with imports declining faster than exports, the trade deficit narrowed from US$ 36.5 billion in July-August 2018-19 to US$ 26.9 billion in the corresponding period of 2019-20. While the current account deficit (CAD) mirrored the movements in the trade deficit, both on a y-o-y and sequential basis, CAD as per cent of GDP widened to 2 per cent in Q1:2019-20 from below one per cent in Q4:2018-19. More than 80 per cent of the trade deficit was financed through invisibles, i.e., net export of services and remittances. Net services exports grew by 7.3 per cent in Q1:2019-20 on a y-o-y basis – primarily driven by software, travel and financial services (Chart III.17b). Revenue growth of major information technology (IT) companies making software exports, improved on a y-o-y basis in Q1:2019-20; an increase of 0.6 per cent in total global IT spending is projected in 2019. Remittances remained stronger in Q1:2019- 20, though the net outgo of payments under income account increased due to higher dividends on foreign investment in Q1:2019-20. The CAD was comfortably met by a mix of foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and external commercial borrowings in Q1:2019-20 with net accretion to reserves to the tune of US$ 14.0 billion. Higher FPI flows, including under the voluntary retention route (VRR) introduced in March 2019, eased external financing conditions. Net inflows under external commercial borrowings to India stood at US$ 6.3 billion in Q1:2019-20 as against an outflow of US$ 1.5 billion a year ago. Net FDI flows at US$ 13.9 billion in Q1:2019-20 were higher than US$ 9.6 billion a year ago. Easing of norms for FDI in single brand retail, contract manufacturing, and coal mining are likely to give a push to FDI inflows and strengthen India’s participation in the global value chain. Notwithstanding outflows from the equity segment in July and August 2019, net FPI purchases (excluding VRR) in the domestic capital market were at US$ 3.3 billion during April-September 2019 as against an outflow of US$ 11.5 billion a year ago. Net flows under non-resident deposits were robust in Q1:2019- 20. India’s forex exchange reserves were placed at US$ 434.6 billion on October 1, 2019 – an increase of US$21.7 billion over the level at end-March 2019.

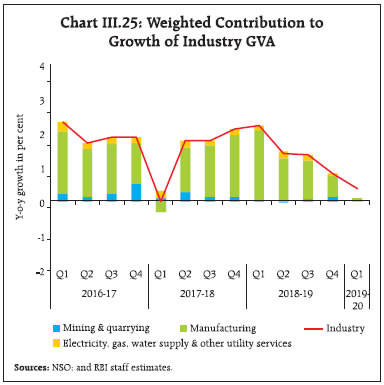

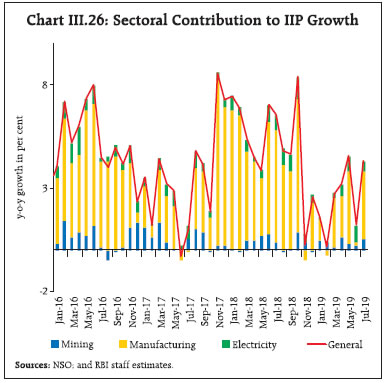

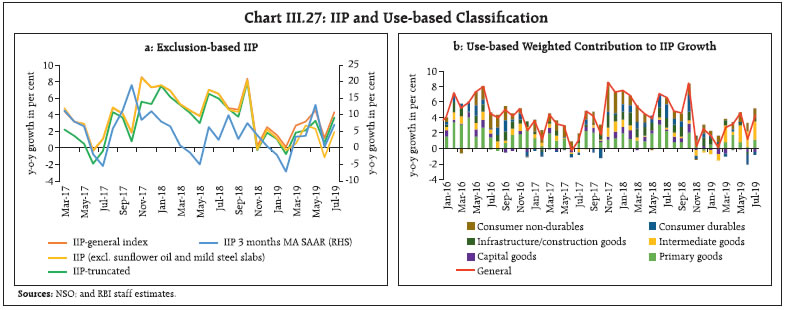

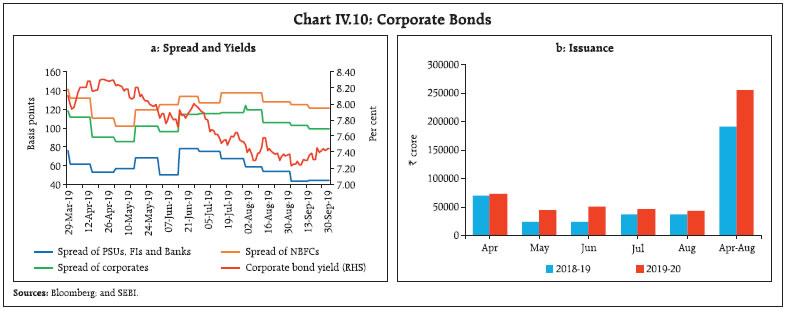

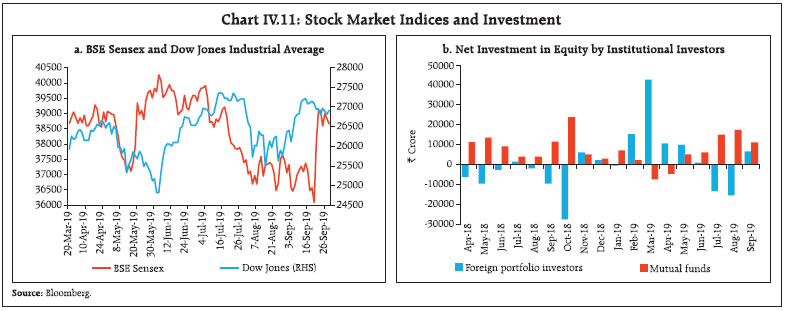

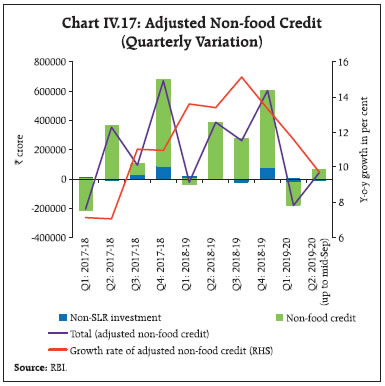

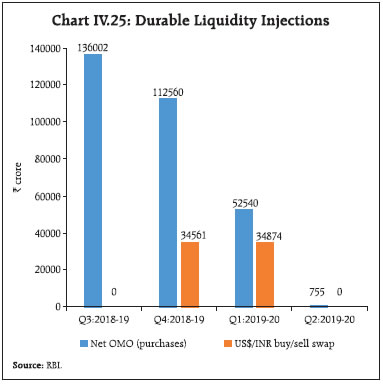

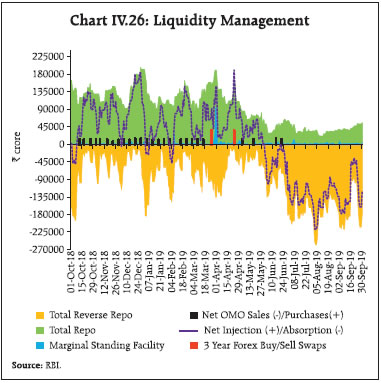

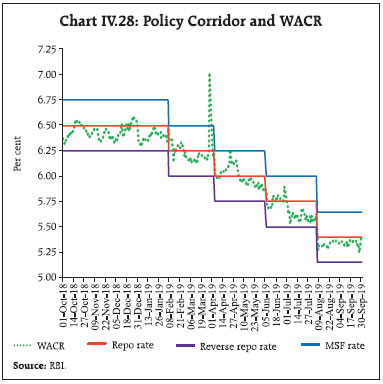

III.2 Aggregate Supply On the supply side, the gross value added (GVA) growth decelerated to 5.7 per cent in Q4:2018-19 and further to a twenty-one-quarter low of 4.9 per cent in Q1:2019-20 (Table III.4). GVA momentum, measured in terms of seasonally adjusted q-o-q annualised growth, also declined sharply in Q1 (Chart III.19). The deceleration in GVA growth (y-o-y) was caused by a significant deceleration in services growth to 6.7 per cent in Q1:2019-20 from 8.2 per cent in Q4:2018- 19, pulled down by construction and ‘financial, real estate and professional services’. Manufacturing registered the second lowest growth in the 2011- 12 series4. Despite some deceleration, public administration, defence and other services (PADO) grew at a healthy rate. Excluding PADO, the GVA growth would have slipped to 5.0 per cent in Q4:2018- 19 and 4.5 per cent in Q1:2019-20 (Chart III.20). Growth in ‘trade, hotels, transport, communication and services related to broadcasting’ registered an uptick sequentially. III.2.1 Agriculture In Q1:2019-20, value added in agriculture and allied activities recovered from contraction in the preceding quarter on the back of higher production of wheat and oilseeds during the rabi season. This was also supported by higher horticulture production by 0.7 per cent to a record of 3,138 lakh tonnes, as per the third advance estimates for 2018-19. | Table III.4: Sector-wise Growth in GVA | | (y-o-y, per cent) | | Sector | 2017-18 (FRE) | 2018-19 (PE) | Weighted Contribution | 2017-18 (FRE) | 2018-19 (PE) | 2019- 20 | | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | | Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 5.0 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 2.8 | -0.1 | 2.0 | | Industry | 6.1 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 | -0.1 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 8.6 | 9.9 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 3.4 | 1.7 | | Mining and quarrying | 5.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 10.8 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 0.4 | -2.2 | 1.8 | 4.2 | 2.7 | | Manufacturing | 5.9 | 6.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | -1.7 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 12.1 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 3.1 | 0.6 | | Electricity, gas, water supply and other utilities | 8.6 | 7.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 9.2 | 6.7 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 4.3 | 8.6 | | Services | 7.8 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 8.6 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 6.7 | | Construction | 5.6 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 4.8 | 8.0 | 6.4 | 9.6 | 8.5 | 9.7 | 7.1 | 5.7 | | Trade, hotels, transport, communication | 7.8 | 6.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 7.1 | | Financial, real estate and professional services | 6.2 | 7.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 9.5 | 5.9 | | Public administration, defence and other services | 11.9 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 14.8 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 15.2 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 7.5 | 10.7 | 8.5 | | GVA at basic prices | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 4.9 | FRE: First Revised Estimates; PE: Provisional Estimates.