Global uncertainty has edged up. In the US, both trade and economic policy uncertainty increased in September. Global growth, however, has broadly held up. Investor sentiments dampened in October, on renewed US-China trade tensions and prolonged US government shutdown, after a phase of buoyancy. The Indian economy displayed resilience amidst broader global uncertainty and weak external demand. High-frequency indicators point to a revival in urban demand and robust rural demand. Headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation moderated sharply in September, marking its lowest reading since June 2017. Introduction Global uncertainty has edged up. In the US, both trade and economic policy uncertainty increased in September. Despite heightened uncertainties, global growth, aided by transitory factors, broadly held up in H1:2025.1 Global financial market movements broadly exhibited optimism and buoyancy despite policy uncertainty and geopolitical tensions. In this environment, the IMF’s World Economic Outlook of October 2025 revised up its 2025 global growth projection, but it still reflects a deceleration compared to 2024. Further, the risks to the growth outlook remain tilted to the downside. Global economic activity held up in September. The global composite purchasing managers’ index (PMI) expanded in September, driven by growth in output and new business. Equity markets in major economies, supported by optimism surrounding Big Tech, the US Fed’s monetary easing and softer energy prices, gained in September. The month of October, however, ushered in selling pressures as investor sentiments dampened on renewed US-China trade tensions and prolonged US government shutdown. In the bond market, US government bond yields fell, following the Fed’s policy rate cut and the escalation of US-China trade tensions. Portfolio flows to major emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) moderated in September as equity segment witnessed outflows due to country-specific risks amidst challenging external environment. Commodity prices generally remained subdued. Prices of precious metals, however, strengthened due to safe-haven demand. Crude oil prices moderated, supported by the ceasefire in the Middle East, and forecasts of a supply glut in 2026.2 Inflation trends remained divergent across economies, as major advanced economies (AEs) continued to grapple with inflation remaining above target levels, while major EMDEs experienced disinflation. Persisting global uncertainties and their potential spillovers to domestic economies, continued to weigh on central banks’ monetary policy decisions. The Indian economy displayed resilience amidst broader global uncertainty and weak external demand. Despite the external sector headwinds, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank have revised India’s growth forecast upwards for the current financial year, underscoring the continued momentum in domestic demand. The high-frequency indicators also pointed to resilient domestic economic activity, with signs of revival in urban demand and robust rural demand. The agricultural sector sustained its growth momentum, supported by above-normal rainfall, and higher kharif sowing. Although manufacturing momentum moderated slightly, business confidence in manufacturing and services reached a six-month peak, reflecting higher optimism. According to the surveys of consumer sentiments, consumer confidence for the current period and the year ahead also improved.3 The capital expenditure of the union government continued to grow at a robust pace. Receipts, however, experienced a slowdown. Merchandise trade deficit widened, on account of an increase in non-oil deficit, to a 13-month high in September. Headline inflation in September fell sharply to its lowest level since June 2017 and remained below the target for the eighth consecutive month. The deflation in food was the key driver of the softening in headline inflation. Core inflation (CPI excluding food and fuel inflation) edged up, reflecting the combined effect of gold price inflation as well as the significant pick-up in housing inflation. The Monetary Policy Committee, in its bi-monthly review of October 2025, kept the policy repo rate unchanged at 5.5 per cent and continued with its neutral stance. The maintenance of the status quo was based on the consideration that the transmission of past front-loaded policy easing was yet to fully play out, and on the need for greater clarity regarding the evolving macroeconomic situation before taking the next policy step. Overall domestic financial conditions remained benign in October (up to October 16), after remaining mildly tight in the latter half of September. System liquidity, on average, remained in surplus during this period. The weighted average call rate – the operating target of monetary policy – hovered close to the policy repo rate in September and October. Average yields on treasury bills moderated while those on certificates of deposit and commercial papers hardened. In the fixed income segment, while the short-end of the government securities yields declined, yields at the longer-end remained flat. Corporate bond yields and spreads increased across tenors and the rating spectrum. Indian equity markets declined in the second half of September as the hike in H-1B visa fees and fresh tariff imposition by the US weighed on investor sentiments. Thereafter, markets gained in early October amidst optimism surrounding the Reserve Bank’s regulatory reform measures aimed at strengthening the resilience and competitiveness of the banking sector, improving the flow of credit, promoting ease of doing business, and enhancing consumer satisfaction. The gains were supported by domestic investors who remained net buyers notwithstanding persistent selling by foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) in the secondary market in September. Net FPI flows, however, turned positive in October amidst renewed participation in primary equity market and sustained investments in the debt segment. The INR witnessed depreciation in September, accompanied by phases of volatility. Key external vulnerability indicators reflect improvement, with the external debt-to-GDP ratio and net international investment position (IIP)-to-GDP ratio strengthening at end-June compared to end-March. Set against this backdrop, the remainder of the article is structured into four sections. Section II covers the rapidly evolving developments in the global economy. Section III provides an assessment of domestic macroeconomic conditions. Section IV encapsulates financial conditions in India, while Section V presents the concluding observations. II. Global Setting Global uncertainty has edged up. In the US, both trade and economic policy uncertainty increased in September. Despite heightened uncertainties, global growth in H1:2025 broadly held up, supported by front-loaded trade and investment activity ahead of US tariff adjustments. Global growth momentum, going forward, is projected to moderate as temporary boost fades and structural challenges re-emerge. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook of October 2025 retained its projection of a decelerated global growth in 2025 compared to 2024, with the balance of risks tilted to the downside. Global growth projection for 2025 was revised upward by 20 basis points (bps) to 3.2 per cent, relative to the July release, largely reflecting the impact of the H1 growth. Growth projections for the major AEs, including US, UK, Euro area and Japan were revised upwards. Among EMDEs, output growth remained robust, led by India, which continued to benefit from resilient domestic demand. The OECD’s Interim Economic Outlook (September 2025) also revised global growth projections upward by 30 bps to 3.2 per cent for 2025, reflecting resilience in the first half of the year (Table II.1). Echoing IMF’s outlook, both OECD and World Bank cautioned that the full impact of US tariff measures and lingering policy uncertainty is yet to unfold, posing downside risks to the global outlook. | Table II.1: Global GDP Growth Projections – Select AEs and EMDEs | | (Y-o-y, per cent) | | Organisation | IMF | OECD | | Projection for | 2025 | 2026 | 2025 | 2026 | | Month of Projection | Oct | Jul | Oct | Jul | Sep | Jun | Sep | Jun | | World | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | | Advanced Economies | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | | | | | | US | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | | UK | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | | Euro Area | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | | Japan | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | | Emerging Market and Developing Economies | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.0 | | | | | | Russia | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | | Emerging and Developing Asia | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.7 | | | | | | India# | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.4 | | China | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 4.3 | | Latin America and the Caribbean | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | | | | | | Mexico | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | | Brazil | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.6 | | Sub-Saharan Africa | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.3 | | | | | | South Africa | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | Note: #: India’s data is on a fiscal year basis (April-March).

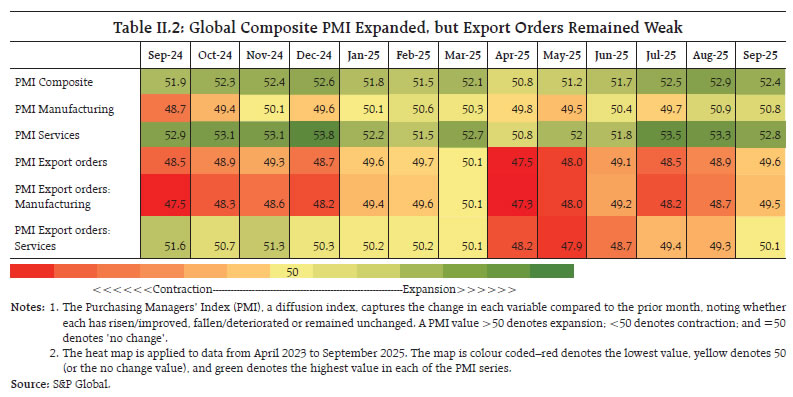

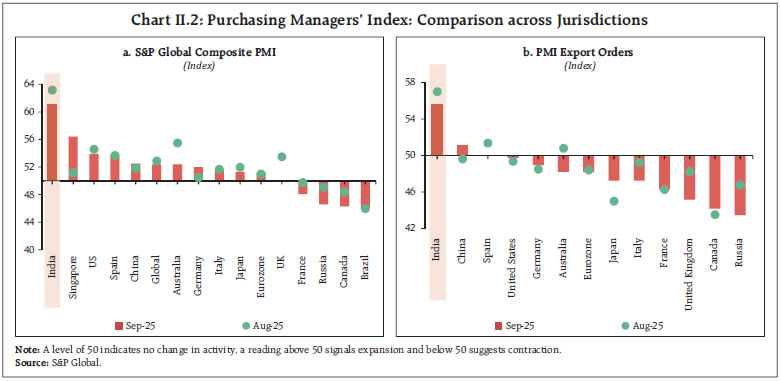

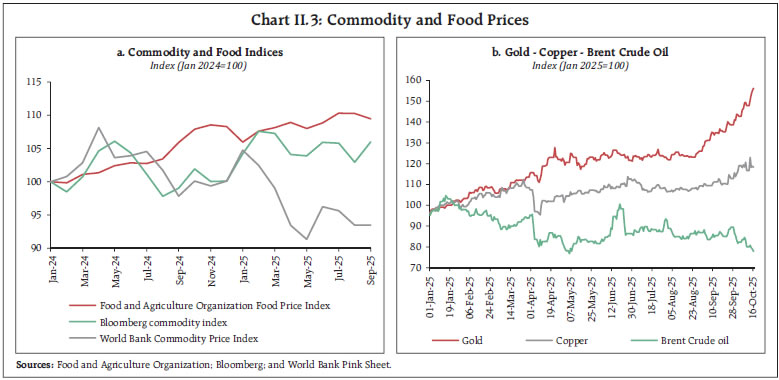

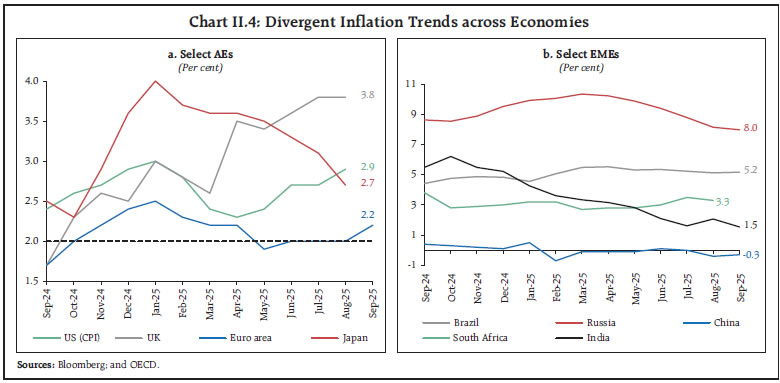

Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2025; and OECD Economic Outlook, September 2025. | Global uncertainty edged up further in August. The US economic and trade policy uncertainty indices rose in September, amidst heightened political and fiscal concerns surrounding the potential government shutdown.4 Financial market volatility in the US and major EMDEs remained largely stable in September. However, it increased in October on country specific developments, including political uncertainty in France, government shutdown in the US and renewed trade tensions (Chart II.1a and II.1b). The global composite PMI, driven by growth in output and new business, expanded in September, though at a slightly slower pace. Both manufacturing and services sectors signalled an expansion, with the services sector continuing to outpace the manufacturing sector. Amidst subdued global demand, new export orders contracted for the sixth consecutive month. While service export orders recorded a modest expansion, manufacturing export orders continued to contract (Table II.2). Economic activity, as per PMI indices, expanded in major AEs, including the US, the UK, Japan, and the Eurozone in September. Among major EMDEs, economic activity expanded in India and China, while it continued to contract in Brazil and Russia (Chart II.2a). New export orders declined across major economies, reflecting subdued external demand, whereas they recorded an expansion in India and China (Chart II.2b). Global commodity prices generally remained subdued in September. Gold and metal prices firmed up, whereas food and crude oil prices softened. Food prices eased as decline in sugar, dairy, cereals, and vegetable oil prices more than offset an increase in meat prices (Chart II.3a). Crude oil prices moderated in October supported by the ceasefire in the Middle East, and forecasts of a supply glut in 20265. Gold prices firmed on safe-haven demand amidst trade tensions, weak economic data from the Euro area, US fiscal uncertainty and expectations of Fed rate cuts (Chart II.3a and II.3b).  Inflation trends remained divergent across economies, as major AEs continued to grapple with inflation remaining above their target levels, while major EMDEs experienced disinflation. In the US, CPI inflation edged up to its highest level since January 2025, although core inflation remained stable. In the Euro area, headline inflation rose in September, driven by higher prices for food and services. The UK recorded its highest inflation rate since January 2024, whereas in Japan, headline inflation eased to its lowest level since November 2024 (Chart II.4a). Among major EMDEs, inflation in Brazil witnessed a modest uptick. China remained in the deflationary zone for the second consecutive month in September. In Russia, inflation, although on a moderating path, remained well above the target. South Africa’s inflation eased in August (Chart II.4b).

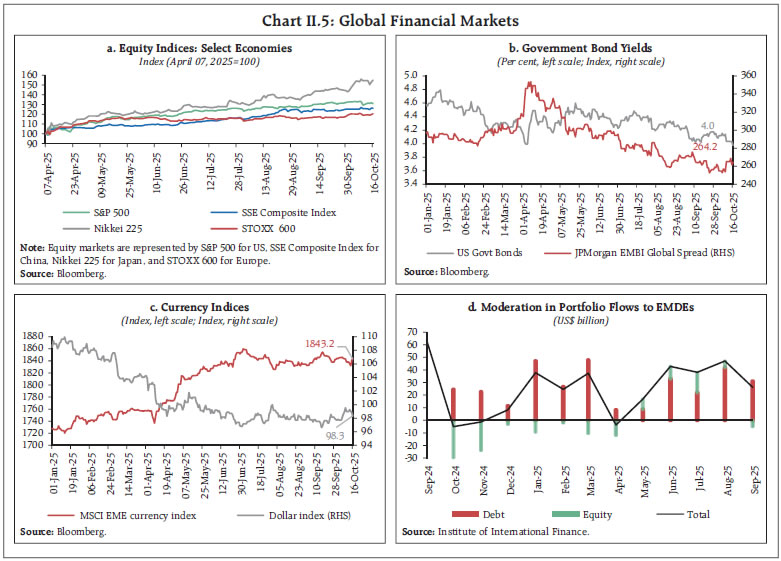

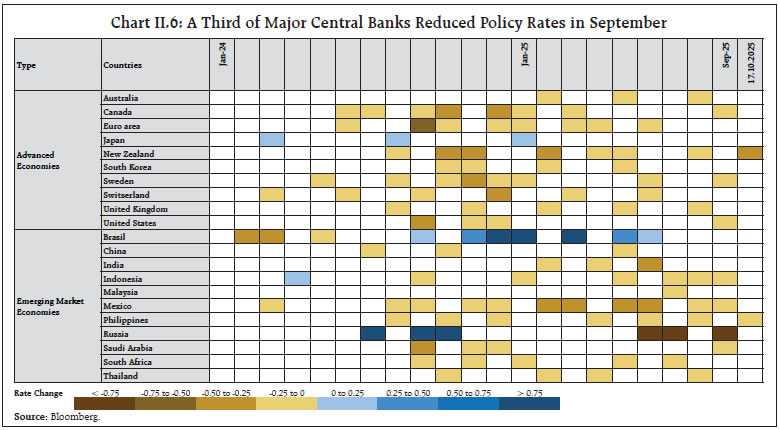

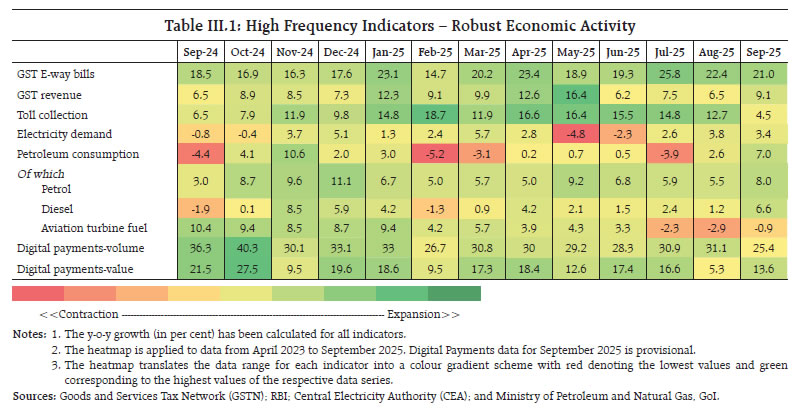

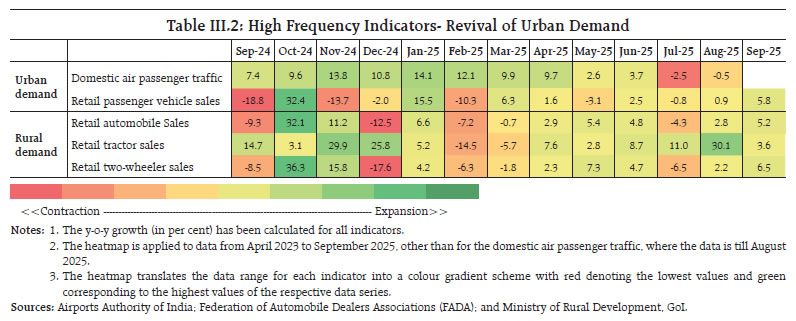

Equity markets in major economies, particularly in the US, gained in September, supported by optimism surrounding Big Tech, the US Fed’s monetary easing, and softer energy prices. The month of October, however, witnessed selling pressures as investor sentiments dampened on renewed US-China trade tensions, and prolonged US government shutdown. In the Euro area, equities posted modest gains, supported by the US Fed’s monetary easing and sector-specific rallies, although the upside was capped by weak Q2 GDP data and renewed trade tensions. Japanese equities gained on a weaker yen and expectations of prolonged accommodative monetary policy stance, but witnessed selling pressures in October on political uncertainty, renewed trade tensions and a strengthening yen. In China, equity markets remained broadly range-bound as trade uncertainty and soft domestic economic indicators weighed on investor sentiment, offsetting support from government stimulus (Chart II.5a).  In the bond market, US government bond yields fell, following the Fed’s rate cut in September. It declined further in October in the wake of escalating US-China trade tensions and the US government shutdown (Chart II.5b). The JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index (EMBI) spread narrowed in September reflecting improved risk appetite as investors exposure to emerging market debt increased amidst expectations of monetary easing in major AEs and favourable domestic inflation conditions in major EMDEs. Renewed fears around trade wars and policy uncertainty in some EMDEs, however, widened the spread in October. The US dollar index moved range-bound during September-October. It initially weakened on softer labour data and rising Fed rate cut expectations but gained later as investors sought safety amidst US fiscal uncertainty and renewed US-China trade tensions. Emerging market currencies appreciated against US dollar in September, following the Fed’s rate cut, but the gains moderated in October on renewed US tariff threats and a prolonged US government shutdown (Chart II.5c). Portfolio flows to EMDEs moderated in September as equity segment witnessed outflows due to country-specific risks amidst challenging external environment (Chart II.5d).  Persisting global uncertainties and their potential spillovers to domestic economies, continued to weigh on central banks’ monetary policy decisions. A third of select major central banks surveyed reduced their policy rate in September (Chart II.6). Among major AEs, the US, Canada, and Sweden reduced their policy rates by 25 bps each in September, whereas the Euro area, the UK, and Japan kept their benchmark interest rates unchanged. Among major EMDEs, Indonesia and Russia reduced their policy rates by 25 bps and 100 bps, respectively, in September, while Malaysia, Brazil, South Africa, and China kept their benchmark rates steady. In October, New Zealand reduced its policy rate by 50 bps, Philippines by 25 bps while Thailand kept its policy rate unchanged. III. Domestic Developments The Indian economy continued to exhibit resilience amidst an uncertain external environment. Indicators of capacity utilisation and domestic demand signalled improvement. Lead indicators of manufacturing and services continued to show a robust expansion. Inflation remained benign, well below the target rate. The IMF revised upwards India’s GDP growth projections for 2025 by 20 bps to 6.6 per cent.6 India’s growth projection for 2026 was, however, revised downwards, reflecting the medium-term impact of the steep US import tariffs. The OECD also revised upwards India’s GDP growth projections for 2025 by 40 bps to 6.7 per cent from the earlier 6.3 per cent underscoring the continued momentum in domestic demand.  The Monetary Policy Committee, in its bi-monthly review of October 2025, kept the policy repo rate unchanged at 5.5 per cent and continued with the neutral stance. The maintenance of the status quo was based on the consideration that the transmission of past front-loaded policy easing is still ongoing, and on the need for greater clarity regarding the evolving macroeconomic situation before taking the next policy step. The Reserve Bank also announced a slew of regulatory reform measures aimed at strengthening the resilience and competitiveness of the banking sector, improving the flow of credit, promoting ease of doing business, and enhancing consumer satisfaction7. Aggregate Demand The high-frequency indicators for overall economic activity remained robust in September. GST e-way bill generation reached a record high as businesses ramped up inventory ahead of the festive season, buoyed by GST reforms. While electricity demand remained stable, petroleum consumption picked up pace. Digital payments recorded robust double-digit growth (y-o-y) in volume and value (Table III.1). Average daily payments value in September 2025 witnessed the sharpest month-on-month uptick in the FY 2025-26 so far. This could possibly reflect a significant pick-up in festive season demand, aided by the GST rate reductions and offers on e-commerce platforms. During September, overall demand conditions showed signs of improvement. Rural demand remained strong, as evidenced by the pick-up in growth of two-wheeler and automobile sales, on the back of good monsoon and robust agricultural activity. Urban demand showed some signs of revival with passenger vehicle sales recording their highest growth in six months (Table III.2).8

Various indicators of employment conditions reflected a mixed picture. The all-India unemployment rate inched up marginally to 5.2 per cent after declining during the last two months. Labour force participation rate and worker population ratio increased to their highest level since May, driven by gains in rural areas. PMI employment indices for both manufacturing and services witnessed some deceleration in September but remained in expansion zone. As per the Naukri JobSpeak index, the growth in white-collar job listings accelerated, led by hiring in insurance, real estate and BPO/ITES. Further, the sharp decline in work demand under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) indicated improving rural employment conditions (Table III.3). During FY 2025-26 (April-August), the key deficit indicators of the union government stood higher, as compared to the corresponding period of the previous year (Chart III.1a).9 This was mainly due to a higher growth in total expenditure, especially capital expenditure, coupled with a decline in tax revenue receipts. The direct tax collections shrank marginally due to a decline in income tax collections.10 The growth in indirect tax collections also witnessed a slowdown owing to a moderation in the growth of GST collections, and a contraction in customs duty collections.11 Key deficit indicators of states during April-August 2025 were also higher than the same period last year (Chart III.1b). This was largely due to a moderation in the growth of states’ GST collections and sales tax/VAT. Growth in revenue expenditure decelerated slightly, while capital expenditure rebounded. Trade As India’s economy remains majorly powered by domestic sources, high US tariffs on India’s exports do not pose a major concern for the overall growth. Despite turbulence in the external sector, India’s merchandise trade during H1:2025-26 remained resilient. During H1, the merchandise trade deficit was higher than that of last year, primarily driven by oil and electronic goods. Exports to the US, which had been buoyant up to August, contracted thereafter, partly reflecting the impact of the 50 per cent tariffs. More recently, on September 25th, the US announced 100 per cent tariff on the pharma sector effective from October 1, 2025. This tariff will be applicable on branded or patented pharmaceutical products, except on companies building their manufacturing plants in the US. For India, US is the largest export destination for pharmaceutical products.12 Out of the total pharma exports from India to the US, generic medicines constitute the most.13 Hence, majority of India’s pharmaceutical exports to the US is expected to remain shielded from the tariff impact.

In September, merchandise trade deficit widened to 13-month high of US$ 32.1 billion from US$ 24.7 billion in September 2024 on account of the increasing non-oil deficit (Chart III.2a).14 While merchandise exports expanded at a moderate pace, merchandise imports surged in September (Chart III.2b).15 Services trade continued to remain favourable in August 2025. The net services export earnings expanded by 12.2 per cent (y-o-y) to US$ 15.6 billion. Services exports growth decelerated in August, reflecting moderation in business services and software services exports. Services imports contracted primarily due to a fall in imports of transportation services (Chart III.3). Aggregate Supply Agriculture Southwest monsoon rainfall at the all-India level stood 8 per cent above normal (Chart III.4a).16 While the excessive rains towards the end of the season have increased the possibility of damage for kharif crops, adequate soil moisture and record high reservoir levels augur well for the upcoming rabi season (Chart III.4b). Aided by good southwest monsoon, the overall acreage under the kharif season surpassed the previous year’s levels (Chart III.5).17 Rice, maize, pulses, and sugarcane saw an increase in sown area, while the area under oilseeds and cotton declined. The combined stock of rice and wheat with the government remains comfortable due to strong procurement operations.18 The increase in minimum support prices (MSP) for the rabi marketing season (April 2026 to March 2027), announced on October 01, seeks to ensure remunerative prices to farmers while incentivising crop diversification (Chart III.6).19

Industry In August, growth in industrial activity, as measured by the year-on-year change in the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), moderated from the previous month following a deceleration in the manufacturing sector growth. The available high-frequency indicators for September suggest robust manufacturing activity. Business expectations under the PMI manufacturing index jumped to a seven-month high, driven by optimism surrounding the GST reforms. Crude and finished steel output growth accelerated, reflecting renewed momentum in infrastructure and construction activity. Automobile production recorded double-digit growth in September, led by the passenger vehicles segment. Stable domestic demand, coupled with a sharp rise in exports sustained the sector’s strong momentum. Going forward, festive demand impulse and the GST rate cut are expected to further boost production and enhance affordability (Table III.4). Over time, there has been a consistent increase in the share of renewable capacity in the total installed capacity, particularly of solar energy (Chart III.7)20. India’s clean energy transition gained momentum in September. India launched its first National Geothermal Energy Policy21, representing a major diversification of its renewable energy portfolio to complement the intermittency of solar and wind power. Fiscal policy also became more supportive of the green transition with reduction in GST on key renewable energy components.22 This would make clean power more affordable and also increase competitiveness of India-made renewable energy equipment.

Services India’s services sector activity showed resilience in September. PMI services continued to show strong expansion in business activity. Growth in port traffic accelerated, led by an uptick in containerised cargo and coal while, retail commercial vehicles sales remained steady. Growth in steel consumption remained stable (Table III.5). Inflation Headline CPI inflation moderated sharply to 1.5 per cent in September from 2.1 per cent in August, marking the lowest year-on-year rate since June 2017 (Chart III.8)23. The decline in headline inflation was primarily due to food and beverages group moving back into deflation territory. The deflation in the food group placed at 1.4 per cent, was on account of a decline in the prices of vegetables, pulses and spices. Inflation in sub-groups such as cereals, eggs, oils and fats, fruits, milk, prepared meals, and non-alcoholic beverages moderated. Meat and fish, and sugar, however, witnessed an increase in inflation (Chart III.9). Fuel and light inflation moderated in September driven by a decline in electricity prices while inflation continued to remain elevated for LPG. Core (i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel) inflation edged up to 4.6 per cent in September from 4.2 per cent in August, driven by ‘personal care and effects’ sub-group, on account of rising gold and silver prices. Core inflation excluding gold and silver also picked up to 3.2 per cent from 3.0 per cent led by increased inflation in housing and ‘pan, tobacco and intoxicants’. Footwear, health, education, transport and communication, and recreation and amusement sub-groups recorded a moderation in inflation. Inflation in both rural and urban areas eased to 1.1 per cent and 2.0 per cent, respectively, in September. While the state level inflation ranged from (-) 1.0 per cent to 9.1 per cent. Majority of states recorded inflation below 2 per cent. A broad-based moderation in state-level inflation rates was observed, as inflation declined or remained stable in 26 states/UTs (Chart III.10).

High-frequency food price data for October so far (up to 17th) point towards a pick-up in cereal prices. Among pulses, prices moderated for gram dal, tur/arhar dal and moong dal. Within edible oils, prices firmed up for mustard oil, sunflower oil and palm oil while groundnut oil prices eased. Key vegetable (tomato, onion, and potato) prices softened, with the decline being most pronounced for tomatoes (Chart III.11).

Retail selling prices of petrol and diesel remained unchanged in October (up to 17th). Kerosene prices witnessed an increase while LPG prices remained unchanged (Table III.6). The PMIs for September recorded a pick-up in the rate of expansion of both input and output prices for manufacturing, with notable increase in input prices for battery, cotton, electronic component, and steel. In contrast, both input and selling prices for services firms decelerated due to slowdown in the growth of new businesses and foreign sales (Chart III.12). | Table III.6: Petroleum Products Prices Remain Broadly Unchanged | | Item | Unit | Domestic Prices | Month-over-month

(per cent) | | Oct-24 | Sep-25 | Oct-25^ | Sep-25 | Oct-25^ | | Petrol | ₹/litre | 101.0 | 101.1 | 101.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | | Diesel | ₹/litre | 90.4 | 90.5 | 90.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | | Kerosene (subsidised) | ₹/litre | 42.9 | 44.3 | 45.4 | -0.5 | 3.4 | | LPG (non- subsidised) | ₹/cylinder | 813.3 | 863.3 | 863.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Notes: 1. ^: For the period October 1-17, 2025.

2. Other than kerosene, prices represent the average Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IOCL) prices in four major metros (Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai and Chennai). For kerosene, prices denote the average of the subsidised prices in Kolkata, Mumbai and Chennai.

Sources: IOCL; Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell (PPAC); and RBI staff estimates. |

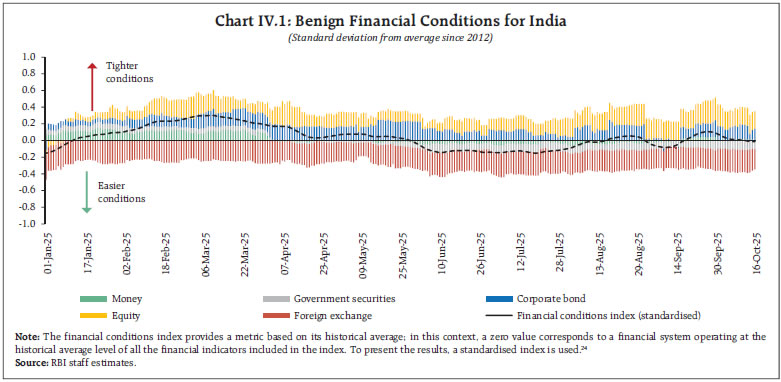

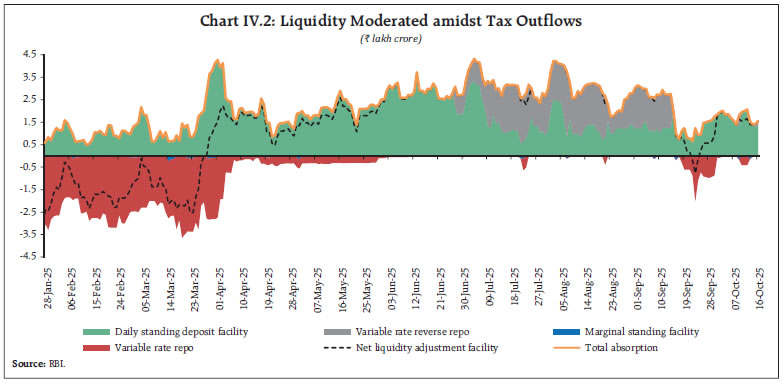

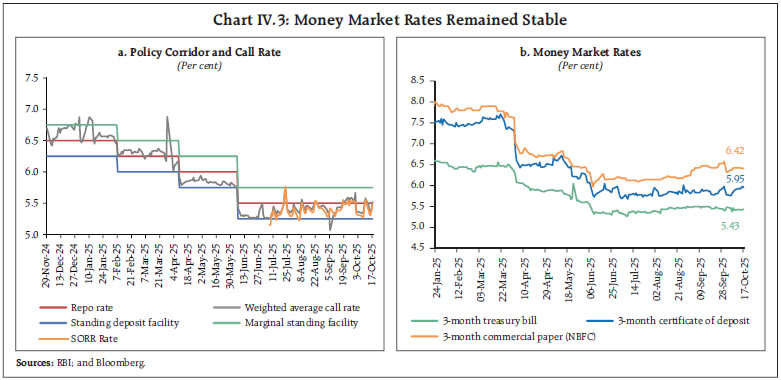

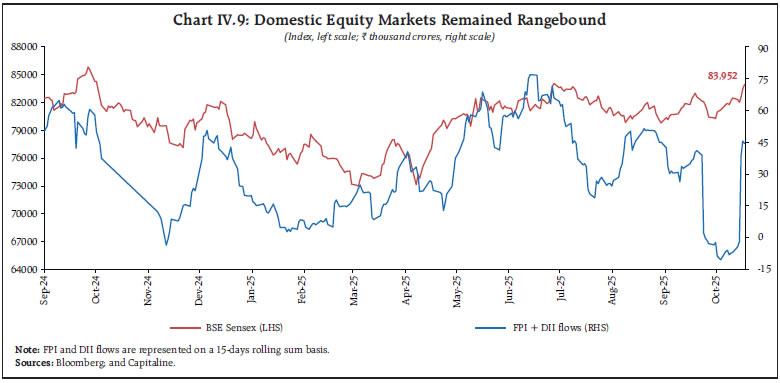

IV. Financial Conditions Overall financial conditions remained benign in October (up to 16th), after remaining mildly tight in the latter half of September, primarily due to easing in the money, equity and corporate bond markets (Chart IV.1).  System liquidity remained in surplus during the second half of September and in October (up to 16th), although an increase in government cash balances, driven by advance tax and GST collections, briefly pushed it into deficit during September 22-24. Since then, government spending and the release of primary liquidity from the 25 bps reduction in the cash reserve ratio25 restored liquidity to surplus conditions. Overall, average net absorption under the liquidity adjustment facility declined to ₹1.0 lakh crore during September 16 to October 16, 2025, from ₹2.6 lakh crore in the preceding one-month period (Chart IV.2). To offset the liquidity tightness during this period, the Reserve Bank conducted 14 variable rate repo auctions (overnight to 6-day maturity) to inject liquidity and align overnight money market rates with the policy repo rate. With overall liquidity conditions in surplus, the average balances under the standing deposit facility remained elevated, and banks’ recourse to the marginal standing facility stayed low.26  The Reserve Bank on September 30, 2025, announced the revised liquidity management framework. The overnight weighted average call rate (WACR) will remain as the operating target for the monetary policy. For managing short-term/transient liquidity, the Reserve Bank would be primarily using the 7-day variable rate repo/ variable rate reverse repo.27 Money Market The WACR generally hovered around the policy repo rate in September and October. It traded above the policy rate during the latter half of September on temporary tightness in liquidity demand due to tax outflows. The WACR moved below the policy rate as liquidity conditions improved since the beginning of October, prompting the RBI to conduct two variable rate reverse repo auctions on October 9 and October 15, 2025. Overall, the WACR was aligned better with the policy rate during September 16 to October 16, 2025, as compared to the preceding one-month period (Chart IV.3a).28 Overnight rates in the collateralised segments – as measured by the benchmark secured overnight rupee rate – largely moved in tandem with the uncollateralised rate. Average yields on three-month treasury bills eased while those on three-month certificates of deposit and commercial papers issued by non-banking financial companies hardened during this period (Chart IV.3b).29 The average risk premium in the money market (the spread between the yields on 3-month commercial paper and 91-day treasury bill) increased.30  Government Securities (G-Sec) Market In the fixed income segment, the shorter end of the yield curve declined during the second half of September and in October (up to October 17), while yields at the longer end remained flat.31 Consequently, the average term spread (the difference between the yields of 10-year G-sec and 91-day treasury bill) inched up marginally during September 16 to October 17, 2025 (Charts IV.4a and IV.4b).32 Corporate Bond Market Corporate bond yields and their spreads over government securities increased across tenors and the rating spectrum (Table IV.1). Fresh issuances in corporate bonds moderated in August over July. On a cumulative basis, total issuances were higher in the current financial year (up to August) compared to the previous year.33 Money and Credit During October, reserve money growth34 remained steady, tracking currency in circulation.35 Growth in money supply remained largely stable (Chart IV.5).36 Credit growth in scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) picked up, with the pace of credit expansion outpacing deposit growth during the fortnight ended October 3, 2025 (Chart IV.6).37 During 2025-26 so far (upto October 3, 2025), the flow of financial resources to the commerical sector increased, mainly due to an inrease in flow of non-food bank credit and flows from non-bank sources including corporate bond issuances and foreign direct investment to India.38 Across key sectors, bank credit exhibited steady growth in August,39 led by personal loans, services, and industry (Chart IV.7).40 Personal loans continued to demonstrate double digit growth. Credit growth for housing remained stable but softened for vehicle loans segment. Credit to services sector remained resilient. Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) − the largest recipient of bank credit within services sector − recorded a pick-up in growth, even as bank credit to trade and commercial real estate decelerated as compared to July 2025. Although credit to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise (MSME) segment softened marginally, it continued to be the prime driver of robust credit growth in the industrial sector. Infrastructure segment observed a marginal uptick in credit growth. Agriculture sector registered an improvement in credit growth. | Table IV.1: Increasing Corporate Bonds Yields and Spread | | | Interest Rates

(Per cent) | Spread (bps) | | (Over Corresponding Risk-free Rate) | | Instrument | August 16, 2025 – September 15, 2025 | September 16, 2025 – October 15, 2025 | Variation | August 16, 2025 – September 15, 2025 | September 16, 2025 – October 15, 2025 | Variation | | 1 | 2 | 3 | (4 = 3-2) | 5 | 6 | (7 = 6-5) | | (i) AAA (1-year) | 6.58 | 6.69 | 11 | 90 | 104 | 14 | | (ii) AAA (3-year) | 7.02 | 7.05 | 3 | 94 | 108 | 14 | | (iii) AAA (5-year) | 7.08 | 7.21 | 13 | 79 | 92 | 13 | | (iv) AA (3-year) | 7.92 | 8.18 | 26 | 198 | 221 | 23 | | (v) BBB- (3-year) | 11.32 | 11.86 | 54 | 566 | 590 | 24 | Note: Yields and spreads are computed as averages for the respective periods.

Source: FIMMDA. |

Deposit and Lending Rates In response to the 100 basis points repo rate cut during the current easing cycle, the weighted average lending rates on fresh and outstanding rupee loans have declined by 58 bps (71 bps on account of interest rate) and 55 bps, respectively (Table IV.2). On the deposit side, the weighted average domestic term deposit rates on fresh and outstanding deposits moderated by 106 bps and 22 bps, respectively. The significant decline in the fresh term deposit rates was driven by a moderation in interest rates on bulk deposits. Across bank groups, the transmission to lending rates was higher for private banks than for public sector banks (Chart IV.8). On the deposit side, the pass-through was higher for public sector banks than for private banks. The union government reviewed and kept the rates on small savings schemes unchanged for Q3:2025-26. The prevailing rates on these instruments exceed the formula-based rates.41 Equity Markets During September and October, Indian equity markets exhibited bidirectional movements in response to a host of domestic and global factors. Markets declined for eight consecutive sessions following the announcement of a steep hike in H-1B visa fees and imposition of fresh sector-specific tariffs by the US. Thereafter, markets rebounded in early October supported by the Reserve Bank’s announcement of measures aimed at strengthening the resilience and competitiveness of the banking sector, promoting ease of doing business and enhancing flow of credit. The gains were supported by DIIs who remained net buyers and FPIs who turned net buyers in October (up to 16th) amidst renewed participation in primary equity market (Chart IV.9). Growth in the secondary market (BSE Sensex and NIFTY 50) remained subdued, whereas primary market activity picked up in September 2025.42 | Table IV.2: Robust Transmission to Banks’ Deposit and Lending Rates | | (basis points) | | | | Term Deposit Rates | Lending Rates | | Period | Repo Rate | WADTDR-Fresh Deposits | WADTDR-Outstanding Deposits | EBLR | 1-Year MCLR

(Median) | WALR - Fresh Rupee Loans | WALR-Outstanding Rupee Loans | | Overall | Interest Rate Effect # | | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | | Tightening Period | | | | | | | | | | May 2022 to Jan 2025 | +250 | 259 | 206 | 250 | 175 | 182 | 191 | 115 | | Easing Phase | | | | | | | | | | Feb 2025 to Aug 2025 | -100 | -106 | -22 | -100 | -40 | -58 | -71 | -55 | Notes: Data on EBLR pertain to 32 domestic banks.

#: The interest rate effect can be arrived at by keeping the weight constant, with the residual change in the weighted average lending rate attributed to the weight effect.

WALR: Weighted Average Lending Rate; WADTDR: Weighted Average Domestic Term Deposit Rate;

MCLR: Marginal Cost of Funds-based Lending Rate; EBLR: External Benchmark-based Lending Rate.

Source: RBI. |

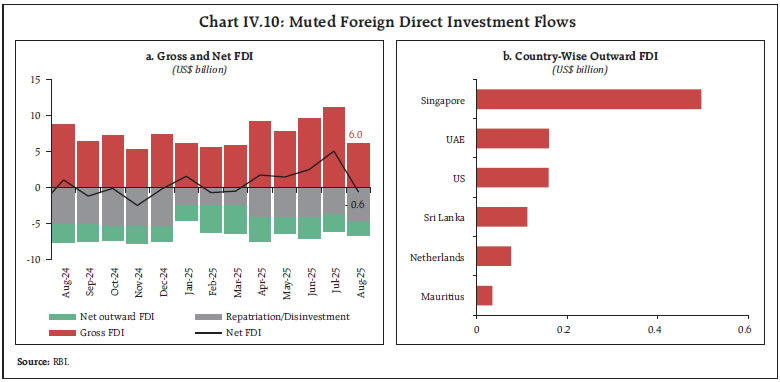

External Sources of Finance Gross inward foreign direct investment (FDI) moderated in August (Chart IV.10a). Singapore, Cayman Islands, the UAE, the Netherlands, and the US accounted for more than three-fourths of total inflows. Manufacturing, computer services, construction, and financial services were the top recipient sectors. Net FDI turned negative in August, due to a moderation in gross inflows and an increase in repatriation. Outward FDI also declined in August. These investments were mainly directed towards financial, insurance and business services, and manufacturing sectors, with Singapore, the UAE, and the US being the major destinations (Chart IV.10b).

Net foreign portfolio investment flows continued to remain negative for the third consecutive month in September (Chart IV.11). This was driven by equity outflows amidst weak investor sentiments on concerns over US tariff measures and the steep hike in H-1B visa fees. In contrast, the debt segment continued to record net inflows, supported by expectations of US rate cut and favourable yield differentials. In October so far (up to October 15), net foreign portfolio investment turned positive on renewed investor’s optimism amidst expected revival in corporate earnings and improved valuations. The registrations of external commercial borrowings moderated during April-August 2025.43 Despite this slowdown, net inflows remained positive at US$ 6.0 billion, as inflows continued to outpace repayments (Chart IV.12). Notably, 39 per cent of the total external commercial borrowing loans registered during this period were earmarked for capital expenditure.

India’s foreign exchange reserves remained adequate, providing a cover for more than 11 months of goods imports and for about 93 per cent of the external debt outstanding at end-June 2025 (Chart IV.13).44 India’s key external vulnerability indicators improved between end-March to end-June 2025. External debt to GDP ratio, short-term debt to reserves ratio and reserves to external debt ratio turned favourable (Chart IV.14). India’s external debt rose by US$ 11.2 billion to US$ 747.2 billion during this period. India’s net International Investment Position improved during Q1:2025-26 (Chart IV.15).45 This improvement was driven by higher accumulation of overseas financial assets by Indian residents relative to the foreign-owned assets in India. As a result, the ratio of India’s international assets to international liabilities improved to 79.2 per cent in June as compared to 77.6 per cent in March.

Foreign Exchange Market The Indian rupee depreciated against the US dollar in September amidst elevated trade tensions, heightened global uncertainties, and persistent foreign portfolio investment outflows (Chart IV.16).

In real effective terms too, the Indian rupee depreciated in September (Chart IV.17a). The depreciation in the real effective exchange rate was mainly driven by the depreciation in the nominal effective exchange rate (Chart IV.17b). V. Conclusion Trade tensions have started to simmer yet again. In the context of rising protectionism in the US, and rising fiscal risks in AEs, IMF’s October World Economic Outlook talks about ‘a new global economic landscape slowly takes shape’.46 The state of flux of the global economy and policies present considerable uncertainties to the macroeconomic outlook. In this scenario, the need for economic resilience has become a key priority. While the Indian economy is not immune to global headwinds, it has so far exhibited resilience, driven by a focus on strong and durable macroeconomic fundamentals – including low inflation, robust balance sheets of banks and corporates, adequate foreign exchange reserves and a credible monetary and fiscal framework. As noted in the Monetary Policy Committee resolution of October 1, 2025, the growth outlook remains resilient, supported by domestic drivers, despite uncertainties on the external front. Domestic structural reforms are helping to somewhat offset the drag on growth from the weakening external demand conditions.47 The current macroeconomic conditions and the outlook, as noted by the MPC, has opened up policy space for further supporting growth.

|