The stability of the banking sector deteriorated marginally in the period since September 2011. The soundness

indicators of banks, however, remained robust. Asset quality pressures persisted while credit growth decelerated,

largely reflecting the slowdown in the economy. As the divergence between credit and deposit growth widened,

banks’ reliance on borrowed funds increased, heightening associated liquidity risks. Going into 2012-13, the

operating conditions for the Indian banks are expected to remain challenging given the weakening global

economic outlook, adverse domestic macroeconomic conditions and policy uncertainties. Banks in India are

likely to be affected due to deleveraging in advanced countries though the direct impact is expected to be limited.

Credit growth of the non banking financial companies has decelerated. Regulatory restraints have been put

in place to rein in the risks posed by exposure of banks to gold loan companies. The stress tests carried out on

banks, incorporating a range of shocks, revealed deterioration in their capital position as compared with the

baseline scenario, but the banking system remained resilient even under extreme stress scenarios. A series of

scenarios and sensitivity stress tests applied on select banks’ derivatives portfolio revealed that they are well

positioned to manage the resultant market risks.

Soundness of Financial Institutions

Banking Stability Map and Indicator1

Risks to the banking sector remain elevated

3.1 Vulnerabilities in the banking sector exhibited a

mixed trend at the end of March 2012 as revealed by the

Banking Stability Map. The soundness and profitability

indicators showed some improvement over the position

as at end September 2011. Soundness indicators,

however, showed a deterioration vis-à-vis their position in March 2011. Strains in asset quality intensified. The

liquidity deficit added to the stress in the banking sector

(Chart 3.1).

3.2 The Banking Stability Indicator, as at end March

2012, pointed to deterioration in the stability of the

banking sector, compared with its position in September

2011. A forecast of the indicator for the next two quarters

surmised that the risks to the banking sector are likely

to remain elevated in the near term (Chart 3.2).

Deleveraging trends in global banking expected to

continue...

3.3 The confluence of funding strains and sovereign

risks led to fears of a precipitous deleveraging process

that could hurt financial markets and the wider economy

via asset sales and contractions in credit (Chapters I and

II). Many European banks have announced mediumterm

business plans for reducing assets. The impact is

likely to differ significantly across regions, with larger

effects expected in emerging Europe than in Asia or Latin

America (Table 3.1). In the Indian context, the claims of

European banks, amounting to US$ 146 billion, formed

53 per cent of total consolidated foreign claims. Of

this, 56 per cent pertained to claims of banks in United

Kingdom.

… with limited impact possible for domestic credit

availability

3.4 The direct impact of the Eurozone crisis on

Indian banks is expected to be limited. The Indian

banking sector is dominated by domestic banks with

foreign banks accounting for only 8 per cent of total

banking sector assets and 5 per cent of banking sector

credit. There could, however, be indirect impact on

Indian banks due to their exposures to other countries,

especially in the Eurozone (Charts 3.3 and 3.4).

3.5 The direct impact of deleveraging is not expected

to be significant on domestic credit availability although

specialised types of financing like structured long term

finance, project finance and trade finance could be

impacted.

Table 3.1 : Consolidated Foreign Claims of European Banks (in US$ billion) |

|

Jun-2011 |

Dec-2011 |

Developing Europe |

1304 |

1137 |

Developing Asia and Pacific |

935 |

841 |

of which, India |

159 |

146 |

Developing Latin America and Caribbean |

855 |

770 |

Source : Locational Banking Statistics - Dec 2011, BIS |

Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs)

Credit and deposit growth weakens, reverberating

slowdown concerns in the economy

3.6 Balance sheet of SCBs expanded by 14.5 per cent

during 2011-12, lower than the growth of 18.8 per cent

for 2010-11. The deceleration was reflected in the growth

rates of both credit and deposits. Credit growth in the

banking sector, at 16.3 per cent in 2011-12, was lower

than the 22.6 per cent recorded in 2010-11. Deposit

growth stood at 13.7 per cent and 17.7 per cent for the

two years respectively. The growth rate of deposits in

2011-12 was the lowest recorded in the past 10 years.

3.7 These trends broadly reflected the slowdown in

the economy, as the nominal GDP growth decelerated

from 18.8 per cent in 2010-11 to 15.4 per cent in

2011-12. Benchmarking of the interest rates on small

savings schemes to market determined rates of interest

as well as availability of liquid funds with higher yield

and associated tax benefits may have also contributed

to the deceleration in growth rate of deposits of banks.

Slowdown in credit driven by slowdown in some

specific sectors…

3.8 The deceleration in credit growth was particularly

marked in case of the priority sector, real estate and

infrastructure segments, which together account for

nearly 60 per cent of banking sector credit (Chart 3.5).

… and amongst public sector banks

3.9 The deceleration was most pronounced in the

credit growth of Public Sector Banks (PSBs) while the old

private sector banks recorded a sharper credit growth of

24 per cent. Expansion of credit to retail and real estate

sectors accounted for the bulk of the growth in credit

among the old private sector banks – a trend which would

need to be carefully monitored, if sustained (Chart 3.6).

CD ratio increased consequent on divergence between

credit and deposit growth rates …

3.10 The credit to deposit (CD) ratio increased to 76

per cent as at end March 2012 (as against 73.5 per cent

as at end September 2011 and 74.3 per cent as at end

March 2011) driven by the divergence between deposit

and credit growth rates in 2011-12. The incremental CD

ratio also remained high at 88 per cent. The incremental

Investment to Deposit (ID) ratio rose sharply on the back

of a 17 per cent growth in investments (Chart 3.7).

… and banks’ reliance on borrowed funds increased

3.11 Banks, during 2011-12, increasingly relied on

borrowings to fund their credit and investment growth.

This was evidenced by the increasing gap between the

combined growth of advances and investments and that

of deposits and capital (Chart 3.8). This was accompanied

by the growing short term maturity mismatches in the

balance sheet of banks (Chart 3.9). The rollover and

liquidity risks associated with these trends will need to

be assessed and managed.

Capital ratios recover as credit growth slows

3.12 The capital ratios of the SCBs improved marginally

since September 2011, primarily due to slowdown

in growth of credit. There was, however, a marginal

deterioration in comparison with the position as on

March 2011. Capital to Risk weighted Assets Ratio

(CRAR) fell from 14.2 per cent as at end March 2011 to

13.5 per cent as at end September 2011, but recovered

to 14.1 per cent as at end March 2012. Core CRAR fell

from 10 per cent as at end March 2011 to 9.6 per cent

as at end September 2011, but rose to 10.3 per cent as

at end March 2012 (Chart 3.10).

Asset quality concerns persist as NPA ratios remain

high

3.13 Asset quality concerns persist as the growth in

non performing assets (NPAs) accelerated and continued

to outpace credit growth. The respondents of the second

Systemic Risk Survey conducted by the Reserve Bank

(Chapter V) also identified asset quality as one of the

critical risks faced by the Indian banking sector.

3.14 The Gross NPA ratio increased to 2.9 per cent as at

end March 2012, as against 2.4 per cent as at end March

2011 and 2.8 per cent as at end September 2011. Net

NPA ratio stood at 1.3 per cent as at end March 2012, as

against 0.9 per cent as at end March 2011 and 1.2 per

cent as at end September 2011. The ratio of NPAs (net of

provisions) to capital also falls short when benchmarked

against the peer economies (Chart 3.11).

Growth in NPAs outpaced credit growth by a wide

margin

3.15 NPAs grew at 43.9 per cent as at end March

2012, far outpacing credit growth of 16.3 per cent.

The divergence in growth rate of credit and NPAs has

widened in the recent period, which could put further

pressure on asset quality in the near term (Chart 3.12).

Accretions to NPAs accelerated

3.16 The slippage ratio3 increased to 2.1 per cent as at

end March 2012 from 1.6 per cent at March 2011 and

1.9 per cent at September 2011.The ratio of slippages

plus restructured standard advances to recoveries

(excluding up-gradations) also exhibited an increasing

trend underscoring the concerns with respect to asset

quality, and the need for proactive management of NPAs

by banks (Chart 3.13).

Restructuring of advances is on the increase…

3.17 Due to a spillover of the global financial

crisis to the Indian economy, certain relaxations 4

were permitted on restructuring on a temporary basis in

the later part of 2008-09, which helped in tiding over the

difficulties faced by the real sector. However, it led to a

significant increase in the level of restructured standard

assets during 2008-09 and 2009-10, after which there

was a deceleration in the amount of restructured assets.

In 2011-12, the quantum of restructured accounts has

again increased sharply, outpacing both credit growth

and growth rate of gross NPAs (Chart 3.14).

…and could weigh on NPA ratios, going forward

3.18 An empirical analysis of the asset quality of

banks’ advances portfolio was conducted by adding

back the advances written off by banks during the last

five years and (separately) assuming that 15 per cent of

restructured accounts slip into impaired category. The

resultant ratios exhibited an increasing trend that calls

for a closer look at the underlying management of NPAs

by banks (Chart 3.15).

Asset quality in some key sectors remained under

strain

3.19 The increase in gross NPAs for the year ending

March 2012 was largely contributed by some key sectors

viz., priority sector, retail and real estate. The growth

rate of NPAs in the infrastructure segment, however,

decelerated as at end March 2012, partially on account

of base effects and sharp moderation in credit to

infrastructure projects (Table 3.2 and Chart 3.16). Certain

sectors like power and airlines saw significant increase

in impairments (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1 : Power and Airlines : Sectors under Stress5

The risks faced by banks on their exposure to the power

sector due to rising losses and debt levels in state electricity

boards (SEBs) and the shortage of fuel availability for power

generation were discussed in the FSR for December 2011.

Potential pressures on asset quality have intensified with

restructuring in bank credit to power sector registering a

sharp increase, especially in the last quarter of 2011-12,

even as impairments as a ratio of outstanding credit has

moderated. Meanwhile, the losses of SEBs have also been

mounting6, adding to the concerns about asset quality in the

sector (Charts 3.17 and 3.18).

|

|

Asset quality of banks’ credit to the airlines industry came

under some stress in recent periods, driven largely by the

performance of some specific airline companies. Sharp increases in impairment and restructuring in the sector saw

the share of this sector in aggregate banking system NPA

and restructured assets rise disproportionate to its share

in banking sector credit (Chart 3.19). There was significant

concentration discernible in distribution of credit to the

airline sector as ten banks accounted for almost 86 per cent

of total bank credit to this sector. As at end-March 2012,

nearly three quarters of the advances of banks, which have

an exposure of above `10 billion to the airline industry, were

either impaired or restructured. PSBs accounted for the major

share of these exposures (Chart 3.20).

|

|

Going forward, the sectors are likely to continue facing

funding constraints and could also be affected by prevalent

policy uncertainties. These could pose challenges to the asset

quality of credit to these sectors.

Further strains on asset quality could emerge; though

the strong capital position provides cushion

3.20 The muted economic backdrop and global

headwinds could lead to further deterioration in asset

quality. The position is not alarming at the current

juncture and some comfort is provided by the strong

capital adequacy of banks which ensure that the

banking system remains resilient even in the unlikely

contingenc y of having to absorb the entire existing stock

of NPAs (Chart 3.21). A series of credit risk stress tests

also testify to the resilience of banks (paragraphs 3.43

to 3.45).

Profitability indicators display mixed trends

3.21 SCBs continued to register healthy profits, though

the growth rate of earnings has decelerated (Chart 3.22).

Return on assets (RoA), return on equity (RoE) and net

interest margin (NIM) have declined marginally as at end

March 2012, relative to end March 2011 (Chart 3.23).

Going forward, the growth of earnings could be affected

due to lower credit off-take and asset quality concerns.

Interest rate swaps dominate off balance sheet assets

of banks

3.22 The aggregate notional amount of off balance

sheet (OBS) assets of the SCBs far exceeded the size

of their on-balance sheet assets (Chart 3.24). The

distribution of total OBS assets (in terms of notional

amount) showed concentration of about 64 per cent in

foreign banks followed by 17 per cent in case of PSBs. In

the case of derivatives, foreign banks constituted 70 per cent of total notional amount, followed by new private

sector banks at 16 per cent. Among the OBS constituents,

the most prominent segment was Interest Rate Swaps

(IRS).

Banks geared to absorb market risks from their

derivatives portfolio; will need to manage the resultant

credit risks

3.23 An analysis of derivatives portfolio of a sample

of banks7 revealed that most banks reported a positive

net mark-to-market (MTM) position. The dominance of

foreign banks in the derivatives segment was evident

as the proportion of gross positive as well as negative

MTM to capital stood, on an average, at around 250 per

cent for foreign banks compared with 16 per cent in case

of the other banks in the sample. Net MTM as a ratio

of capital varied between a positive of 30 per cent to a

negative of 10 per cent (Charts 3.25 and 3.26).

3.24 A series of stress tests was carried out on the

derivatives portfolio by the select banks based on

a common set of historical scenarios and random

sensitivity shocks (Box 3.2). The post-stress net MTM

position was positive for most banks suggesting that

the banks are well geared to absorb adverse market

movements. However, banks remained exposed to

the risks of counterparty failure, especially in case

of disputes with clients over payment, as had been

evidenced in the past.

Non Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs)

Credit growth decelerated amidst declining asset

quality and profitability

3.25 NBFCs experienced deceleration in growth

rate of credit though the credit growth continued to

outpace that of the banking sector. Bank credit to NBFCs

accelerated as did the reliance of NBFCs on bank credit

as a source of funding. This could pose risks for NBFCs if

banks are not in a position or unwilling to extend credit

to the sector (Chart 3.27).

3.26 The financial soundness indicators of systemically

important non-deposit taking NBFCs (NBFC-ND-SIs)

revealed a deteriorating trend with respect to soundness,

asset quality and profitability (in terms of RoA). The

CRAR remained above the regulatory requirement of

15 per cent, though it declined over the review period, (Chart 3.32). The downward movement in CRAR could

partially be explained by the increasing asset base of the

NBFCs. Further, the RoA remained healthy at around

2 per cent.

Box 3.2 : Stress Testing of Derivatives Portfolio of Select Banks

A stress testing exercise on derivatives portfolio of

a cross section of banks was undertaken. The stress

tests consisted of six historical scenarios and four

interest rate and exchange rate sensitivity shocks8.

The impact of the tests exhibited considerable

variance across banks and across bank groups. In terms of increase in negative MTM, foreign banks

were impacted significantly while the impact on

the rest of the bank groups was muted. Further,

the shocks used for sensitivity analysis caused the

maximum stress, in case of most banks, relative to

the historical scenarios (Charts 3.28 and 3.29).

|

|

The impact on the net MTM positions of banks in

the sample, post application of the stress conditions,

was observed to be relatively muted in most cases.

The shocks used for sensitivity analysis caused

the maximum stress for most banks relative to

the historical scenarios with the average change in Net MTM being around 344 per cent for the

sensitivity analysis compared with 66 per cent

for scenario analysis. However, there were a few

outlier banks where the impact was significant and

these banks would need to carefully manage the

underlying risks (Charts 3.30 and 3.31).

Rapid rise of gold loan companies could be a cause

of concern

3.27 The exponential growth in balance sheets of

NBFCs engaged in lending against gold in recent years coupled with the rapid rise in gold prices along with

expansion in the number of their branches could be a

cause of concern (Box 3.3). The gold loan companies 9

exhibited high dependency on the banking system for

their resources which could pose risks to the banks, in

case the business model of these companies falters. This

growing interconnectedness of gold loan companies

with banks was sought to be addressed through recent

regulatory measures viz., the de-recognition of priority sector status of bank finance to NBFCs for on-lending

against gold jewellery and through the prescription of a

lower exposure limits on bank finance to NBFCs. Further,

as a prudential measure, the Reserve Bank also directed

the gold loan companies to maintain a minimum Loanto-

Value (LTV) ratio of 60 per cent for loans granted

against the collateral of gold jewellery and a minimum

Tier I capital of 12 per cent by April 1, 2014.

Box 3.3 : Gold Loan Companies and Associated Risks

Lending against the collateral of gold is not a recent

phenomenon, though there has been a spurt in this activity in

recent years with NBFCs emerging as prominent players in the

market for ‘gold loans’. The share of NBFCs in total gold loans

extended by all financial institutions, showed a marked increase

between March 2010 and 2011. Individuals are the largest

borrowers against gold from NBFCs and account for 95 per cent

of the total gold loans.

The data related to these NBFCs shows that the total asset size

increased sharply from ` 54.8 billion as at end March 2009 to

` 445.1 billion as at end March 31, 2012. The growth has largely

been accompanied by an escalation in borrowings. There is

significant concentration among the companies, as the growth

in advances is mainly contributed by two companies. The

borrowings of these two companies increased by nearly

200 per cent between March 2010 and 2011.

Nevertheless, there are several concerns pertaining to this

segment of the NBFC sector. The main concerns being:

(i) Concentration Risk

With more than 90 per cent of the loan assets being

collateralised by only one product viz. gold jewellery, the

business model of gold loan companies has inherent concentration risks. The risks, however, would materialise

only in case of a steep adverse movement in gold prices.

(ii) Operational Risk

The gold loan companies thrive on the promises of

disbursement of quick /easy loan. Considering the extremely

speedy disbursal being promised by these companies,

quality of due diligence including adherence to Know Your

Customer (KYC) norms, establishing ownership and quality

of the gold, etc. could be compromised.

(iii) Concerns on Private Placement of NCDs on a Retail Basis

The gold loan companies have resorted to frequent

issuances of short term retail non convertible debentures

(NCDs), especially through private placement for meeting

their credit needs. Concerns arise as some of these NCDs

carry the features of ‘public deposits’, but these entities

are not regulated in a manner akin to deposit taking NBFCs.

(iv) Reliance on borrowings, especially bank funds

The business model of the gold loan companies is driven

by borrowings, of which, bank finance forms the major

component and is increasing at a fast rate. Any adverse

development in recovery by these NBFCs or an adverse

movement in gold prices may have a spill-over impact on

the asset quality of the banks.

Urban Co-operative Banks (UCBs)

UCBs show improvement in performance

3.28 The performance of Scheduled UCBs (SUCBs) as

at end March 2012 has shown improvement during the

review period (Chart 3.33).

Regional Rural Banks (RRBs)

Strain in asset quality evident

3.29 RRBs, which constituted about 1.5 per cent of the

assets of the financial system, showed robust growth as

at end March 2012, even as asset quality deteriorated

(Charts 3.34 and 3.35).

Insurance Sector10

Non life sector indicated robust growth while life

sector declined

3.30 The non life insurance industry grew by

23.2 per cent, at end March 2012, as against a growth of

22.4 per cent as at end March 2011. The life insurance industry showed a decline of 9.2 per cent in the first

year premium collected in 2011-12, against a growth of

15.1 per cent in 2010-11.

Challenges lie ahead in wake of Solvency II regime

3.31 The Indian insurance sector is governed by a

factor based solvency regime which is comparable to

Solvency I 11. This framework is rule based and reflects

various risks at the industry level while implicit margins

embedded in various elements for valuing assets,

liabilities and solvency margins make the solvency

framework prudent and robust.

3.32 Solvency II is a risk-based regulatory regime that

will apply to almost all insurance establishments in the

European Union (EU). The regime introduces economic

risk-based solvency requirements and aims to bring in a

change in perception that capital is not the only mitigant

against failures. Instead of statutory provisioning,

Solvency II provides for provisioning based on the

(market consistent) ‘Best Estimate’. Given that the joint

venture partners of a number of insurance companies

operating in India are EU based entities, the Indian

operations have also been assessed for the purpose of

Solvency II. While the level of preparedness of these

entities would be much higher, greater challenges exist

with respect to the public sector insurers both in the

life and non-life segments.

3.33 The current capital regime in India is not in

complete consonance with Solvency II and embarking on

the framework would necessitate addressing a range of

challenges in terms of assessment of risks, development

of internal models, adequacy of data, capacity building

both within IRDA and in the insurance industry. As a

first step in this direction, IRDA has set up a Committee

to examine the solvency regime in select jurisdictions

and to make its recommendations on the Solvency II

regime in India.

Pension Funds12

3.34 India’s pension ecosystem is enormous and is

growing rapidly. At one end of the spectrum are Defined

Benefit (DB) pension schemes of which the two main

schemes are the pre-reform civil services pension scheme of the Centre/states (which has been replaced

by the National Pension System for the new recruits)

and the ‘organised sector’ social security scheme

operationalised by the Employees’ Provident Fund

Organisation (EPFO). Besides, in the defined benefit

category, there are a number of schemes which are run

by the central and state governments, of which the

largest is the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension

Scheme. The state governments run a number of

occupational pension schemes, a large number of which,

relate to the trades in the unorganised sector and mainly

target the population below the poverty line.

3.35 At the other end of the spectrum are the Defined

Contribution (DC) Schemes of which the National

Pension System (NPS) introduced from January 2004 is

the most important addition to the Indian pension

sector. The NPS was initially introduced as a replacement

pension scheme for the civil services. The scheme was

first adopted by the central government and then by the

state governments, except for West Bengal, Kerala and

Tripura. In 2009, the NPS was extended to the private

sector and, in 2010, the Government of India introduced

a co-contribution scheme (called ‘Swavalamban’) on the

NPS platform for the unorganised sector. The DC space

is also populated by a number of schemes that are run

by insurance companies for private individuals and

corporates.

3.36 In the case of the DB schemes, the biggest

challenge is the quantification of the liabilities. Since

the pre-2004 pension scheme is indexed to inflation and

wage increases recommended by the Pay Commission,

it becomes difficult to project the pay-outs far into the

future. The problem is compounded by the fact that it

is a ‘Pay As You Go’ system which implies that this is an

unfunded liability. Any large increase in the pension

liability will have a direct impact on the fiscal deficit. The

2012-13 budget estimated a total outflow of `631 billion

on pensions and retirement benefits of central

government employees alone, which is an increase of

12 per cent over the revised estimate of `561 billion in

2011-12. In the 1970s and 1980s, recruitment by the

Government expanded rapidly, though it was contained in the 1990s. Pension payments to the recruits of earlier

decades will soon start looming large. The outflows are

expected to rise as the cohort of recruits between 1970s

and 1980s retire. In the case of the EPFO, it is a DB

scheme which is partially funded by the contributions

made by the employer and the employee. However, since

the benefits are fixed and are sticky downwards, any

shortfall will have to be made good by the

Government. According to the Report of the Expert

Committee on Employees’ Pension Scheme (EPS), 199513,

there is underfunding in the EPS at the present rate of

contributions and sustainability of the scheme would

require upward revisions. Moreover, the Employees’

Pension Fund had a corpus of about `1420 billion as on

March 31, 2011. The large magnitude is a pointer to

systemic risk, if magnitude is any criteria. In the case of

several DB schemes, currently under implementation

and newly announced, the lack of liability computation

especially in a world of rising life expectancy can be a

potential source of fiscal stress in years where there are

large payouts.

3.37 Identifying systemic risks for DC pension systems

is a challenge as prima-facie, one does not find reasons

when all the risks are transferred and diffused to a large

number of subscribers whose benefits are left undefined,

by definition. The task becomes more challenging when

the pension regulator has a limited mandate to regulate

only the National Pension System and no identification

methodology for systemic risks is available and

implemented. The miniscule size of NPS intuitively

renders negligible possibilities or potentials of posing

any systemic risk. The NPS (a Defined Contributionunprotected),

by definition, rules out the requirement

of solvency or capital requirement related stress test. At

best, some kind of scenario analysis can be contemplated,

not from the perspective of systemic risk threat but for

effectively addressing public disclosure risk issues. This

is specifically relevant for the return and benefit

projection on which illustrations could be based. A

sensitivity testing could also be relevant when the risk

of a particular factor is tested on an institution or

portfolio (such as equity market decline or adverse

interest rate movements). Similarly a full range of stress tests covering broad range of modeling techniques can

be contemplated to effectively communicate the risks

passed on to the subscribers using historical scenarios

or hypothetical (usually extreme) events. The modeling

can be deterministic or stochastic.

3.38 International standard setting organisations such

as International Association of Insurance Supervisors

(IAIS) and Bank for International Settlements (BIS) have

outlined two main roles for stress testing: (a) To ascertain

whether financial institutions have sufficient financial

resources to meet their commitments (not required for

DC pensions which do not have set liabilities to meet)

(b) As a general risk management tool, which can be

used to ascertain the impact of various factors or

scenarios on financial institutions (DC pensions do not

have capital requirements).

3.39 However, stress tests can help to develop and

assess alternative strategies for mitigating risks. There

could be three different uses of stress tests. First, the

pension supervisor can analyse the results of tests

undertaken by pension funds as a part of general

oversight. Second, supervisors can impose standard tests

for all supervised entities for comparative purposes or

to establish the state of the industry as a whole. Third,

supervisor could optionally request particular tests to

be imposed on specific institutions where they have

concerns. At present, internationally, there is no

guidance available to be drawn from the comparative

analysis on the elements and factors that should be

considered by both pension funds and pension

supervisors in designing, applying and evaluating stress

testing models.

3.40 Similar to the rigorous exercises undertaken by

the Expert Committee, the conventional broad range of

modeling techniques and solvency related tests can be

applied to these DB pension plans to ensure that

government has sufficient financial resources to meet

their (future) commitments. Stress tests with respect to

particular risk factors (such as general economic decline,

interest rate movements, inflation) can help to develop

and assess alternative strategies for mitigating risk.

Resilience of Financial Institutions

3.41 The resilience of the financial institutions was

assessed through a series of stress tests which imparted

extreme but plausible shocks14 based on supervisory data

pertaining to end-March 2012. The resilience of SCBs to

various stress scenarios was tested using both the top

down and the bottom up approaches as also through a

series of macro stress tests15. A number of single factor

sensitivity stress tests were also carried out on scheduled

UCBs and NBFC-ND-SIs (Non deposit taking systemically

important NBFCs) to assess their vulnerabilities and

resilience under various scenarios.

Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs)

3.42 A series of top down stress tests incorporating

credit, foreign exchange, equity, interest rate and

liquidity risks were carried out for the banking system

(60 SCBs comprising 99 per cent of total banking sector

assets). The same set of shocks were used by 25 select

SCBs (comprising about 75 per cent of total assets) to

conduct bottom up stress tests. The bottom up stress

tests broadly reflected the results of the top down stress

tests and reconfirmed the resilience of the banking

system to a wide range of shocks.

Credit risk remains the main source of vulnerability

for SCBs

3.43 The impact of shocks under different credit

risk scenarios for banks as on March 2012 shows that

the system level CRAR remained above the required

minimum of 9 per cent and the system is reasonably

poised to withstand the shocks; although some banks,

including a few large banks, could be under stress as

their CRAR would fall below 9 per cent (Table 3.3 and

Chart 3.36).

Banks remain resilient to sectoral credit risk shocks

3.44 The analysis of a credit risk shock emanating

from important sectors viz. agriculture, power, real

estate, telecom and priority sector revealed that the

maximum impact was seen in the case of shocks to the

priority sector followed by shocks to the real estate and

agriculture sectors. The banks were, however, able to

absorb the shocks (Table 3.4).

Table 3.3 : Credit Risk: Gross Credit - Impact on Capital and NPAs |

(Except number of banks, figures are in per cent) |

|

System Level |

Impacted Banks

(CRAR < 9%) |

Impacted Banks

(Core CRAR < 6%) |

CRAR |

Core

CRAR |

NPA

Ratio |

Number

of Banks |

Share in

Total

Assets |

Number

of Banks |

Share

in Total

Assets |

Baseline: |

All Banks |

14.1 |

10.3 |

2.9 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Select 60 Banks |

13.9 |

10.1 |

2.8 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Shock 1: |

11.9 |

7.9 |

5.8 |

5 |

6.7 |

11 |

30.0 |

Shock 2: |

11.1 |

7.2 |

7.2 |

12 |

30.2 |

18 |

41.9 |

Shock 3: |

12.7 |

8.8 |

4.2 |

3 |

1.5 |

4 |

6.5 |

Shock 1: NPAs increase by 100 per cent |

Shock 2: NPAs increase by 150 per cent |

Shock 3: NPAs increase due to 40 per cent of restructured standard advances turning NPAs |

Source: Supervisory Data and RBI staff calculations |

|

Table 3.4 : Credit Risk: Sectoral – Impact on Capital and NPAs |

(Per cent) |

|

System Level |

CRAR |

Core CRAR |

NPA Ratio |

| Baseline: |

All Banks |

14.1 |

10.3 |

2.9 |

Select 60 Banks |

13.9 |

10.1 |

2.8 |

Shock: 5 percentage points increase in NPAs in each sector |

Power |

13.7 |

9.8 |

3.2 |

Telecommunication |

13.8 |

10.0 |

3.0 |

Agriculture |

13.4 |

9.6 |

3.5 |

Real Estate |

13.3 |

9.4 |

3.7 |

All 4 Sectors : Agriculture + Power + Real Estate + Telecom |

12.6 |

8.8 |

4.7 |

Priority Sector |

12.8 |

8.9 |

4.4 |

Source: Supervisory Data and RBI staff calculations |

Credit concentration risk was not significant

3.45 A study of the concentration of credit portfolio

of banks revealed that, at the system level, the

concentration appeared moderate, though the degree

of concentration was higher in some individual banks

(Table 3.5). The average exposure of the banks to the

largest group borrower stood at 4.7 per cent of total

advances. The maximum exposure was, however, much

higher at 26.1 per cent.

Banks able to withstand interest rate shocks

3.46 The resilience of SCBs to shocks involving both

parallel and non-parallel shifts in the yield curve was

assessed. The tests were carried out separately for the

banking and trading books. The results carried out on the

trading book suggest that the impact of interest rate risk

would be limited and no bank is impacted adversely. The

results of the banking book also suggest that the banking

system could withstand the assumed stressed scenarios,

though the CRAR of some individual banks slip below

the regulatory minimum. The impact is maximum in

case of a parallel upward shift of the INR yield curve by

250 basis points (bps) (Table 3.6 and Chart 3.37).

Impact of adverse exchange rate and equity price

movements would be limited

3.47 The impact, of appreciation/depreciation of

currencies by 10/20 per cent, on banks’ individual net

open bilateral currency positions was assessed. The

stress tests results indicate that the impact will not be

significant. The impact of a fall in the equity prices by 40

per cent on banks’ capital revealed that the shock has a

marginal impact as the equity market exposure of banks

was not very significant. The system level CRAR fell to

13.4 per cent, under stress, from the baseline of 14.1

per cent. For all banks, the post-stress CRAR remained

above 9 per cent.

SLR investments key in mitigating liquidity risks

3.48 Stress scenarios assessing the resilience of banks

to liquidity risk16 evidenced deterioration in the liquidity

position of some banks. The availability of Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) investments, however, helped the

banks to ward off the liquidity pressure (Table 3.7).

Table 3.5 : Credit Risk: Concentration- Impact on Capital and NPAs |

(Except number of banks, figures are in per cent) |

|

System Level |

Impacted Banks

(CRAR < 9%) |

Impacted Banks

(Core CRAR < 6%) |

CRAR |

Core

CRAR |

NPA

Ratio |

Number

of Banks |

Share in

Total

Assets |

Number

of Banks |

Share

in Total

Assets |

Baseline: |

All Banks |

14.1 |

10.3 |

2.9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Select 60 Banks |

13.9 |

10.1 |

2.8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Shock 1 |

12.7 |

8.8 |

5.6 |

1 |

0.19 |

1 |

3.0 |

Shock 2 |

12.2 |

8.3 |

7.8 |

1 |

0.19 |

2 |

5.1 |

Shock 3 |

11.6 |

7.7 |

10.6 |

1 |

0.19 |

9 |

30.4 |

Shock 4 |

12.3 |

8.4 |

7.5 |

1 |

0.19 |

2 |

5.1 |

Shock 1: Top individual borrower defaults

Shock 2: Top two individual borrowers default

Shock 3: Top three individual borrowers default

Shock 4: Top group borrower defaults |

Source: Supervisory Data and RBI staff calculations |

Table 3.6 : Interest Rate Risk: Banking Book-Impact on Banks |

(Except number of banks, figures are in per cent) |

|

System Level |

Impacted Banks

(CRAR < 9%) |

Impacted Banks

(Core CRAR < 6%) |

CRAR |

Core

CRAR |

Number

of Banks |

Share in

Total

Assets |

Number

of Banks |

Share

in Total

Assets |

Baseline: |

All Banks |

14.1 |

10.3 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Select 50 Banks |

13.9 |

10.1 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Net Impact on Banking Book (Earnings + Portfolio) |

Shock 1 |

10.9 |

7.1 |

16 |

25.9 |

18 |

41.3 |

Shock 2 |

13.9 |

10.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

Shock 3 |

13.4 |

9.6 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

Shock 4 |

12.0 |

8.3 |

3 |

3.4 |

7 |

10.5 |

Income Impact on Banking Book (Earnings) |

Shock 1 |

13.8 |

10.0 |

1 |

1.8 |

1 |

1.8 |

Shock 2 |

13.9 |

10.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

Shock 3 |

13.8 |

10.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

Shock 4 |

13.8 |

10.0 |

1 |

1.8 |

1 |

1.8 |

Valuation Impact on Banking Book (Duration Gap Analysis) |

Shock 1 |

11.0 |

7.2 |

14 |

23.1 |

17 |

40.2 |

Shock 2 |

13.9 |

10.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

Shock 3 |

13.4 |

9.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

Shock 4 |

12.1 |

8.4 |

2 |

1.5 |

7 |

10.2 |

Shock 1: Parallel upward shift in INR yield curve by 250 bps

Shock 2: Parallel downward shift by 250 bps

Shock 3: Steepening of the INR yield curve, with interest rates increasing by 100

bps linearly spread between 1-month maturity and more than 10 year

maturity

Shock 4: Inversion of the INR yield curve with one-year rates shifting upwards

linearly by 250 bps and 10-year rates dropping by 100 bps |

Source: Supervisory Data and RBI staff calculations |

|

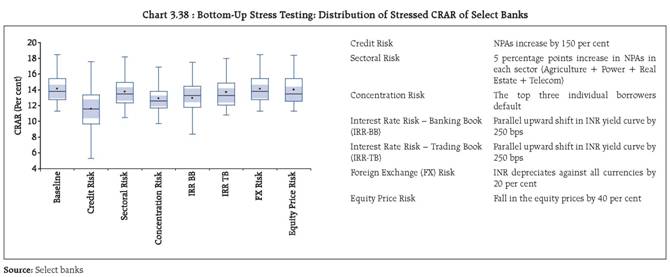

Bottom-up stress tests also reflect resilience of the

banking system

3.49 The results of the bottom up stress tests carried

out by select banks (paragraph 3.42) also testified to the

general resilience of the banks to the different kinds

of sensitivity analysis. As in the case of the top down

stress tests, the impact of the stress tests were relatively

more severe on some banks with their post-stress

CRAR position falling below the regulatory minimum

(Chart 3.38).

Table 3.7 : Liquidity Risk: Impact on Banks |

(Except number of banks, figures are in per cent) |

|

Liquid Assets Definition |

Banks Facing Deficit |

Liquid Assets Ratio |

No. of Banks

|

Deposits Share |

Assets Share |

Baseline: 1 |

Cash, Excess CRR, Inter-bank-deposits, All-SLR-Investments |

22.9 |

Shock 1: |

10 per cent total deposit withdrawal 30 days |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

14.2 |

Shock 2: |

3 per cent deposit withdrawal each day for 5 days |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

11.0 |

Baseline: 2 |

Cash, Excess CRR, Inter-bank-deposits-maturing-within-1-month and Investments-maturing-within-1-month |

7.4 |

Shock 1: |

10 per cent total deposit withdrawal 30 days |

40 |

85.4 |

81.2 |

-2.8 |

Shock 2: |

3 per cent deposit withdrawal each day for 5 days |

44 |

90.7 |

87.0 |

-6.7 |

Baseline: 3 |

Cash, Excess CRR, Inter-bank-deposits-maturing-within-1-month, Excess SLR |

3.1 |

Shock 1: |

10 per cent total deposit withdrawal 30 days |

57 |

99.9 |

99.6 |

-7.7 |

Shock 2: |

3 per cent deposit withdrawal each day for 5 days |

57 |

99.9 |

99.6 |

-11.8 |

Baseline: 4 |

Cash, CRR, Inter-bank-1mon, Inv-1mon |

11.2 |

Shock 1: |

10 per cent total deposit withdrawal 30 days |

26 |

59.9 |

56.8 |

1.3 |

Shock 2: |

3 per cent deposit withdrawal each day for 5 days |

36 |

77.8 |

733 |

-2.4 |

Baseline: 5 |

Cash, CRR, Inter-bank-1mon, Excess SLR |

6.8 |

Shock 1: |

10 per cent total deposit withdrawal 30 days |

54 |

99.5 |

98.9 |

-3.5 |

Shock 2: |

3 per cent deposit withdrawal each day for 5 days |

57 |

99.9 |

99.6 |

-7.4 |

Source: Supervisory Returns and RBI staff calculations |

|

Urban Co-operative Banks

UCBs vulnerable to credit risk shocks…

3.50 Stress tests on credit risk were carried out for

Scheduled UCBs (SUCBs) using their balance sheet data

as at end-March 2012. The impact of credit risk shocks on

the CRAR of the banks was assessed under two different

scenarios assuming an increase in the gross NPA ratio

by 50 per cent and 100 per cent respectively. The results

show that SUCBs could withstand shocks assumed under

the first scenario easily, though it would come under

some stress under the second scenario (Chart 3.39).

…as also to liquidity risks

3.51 Stress tests on liquidity risk were carried out

under two different scenarios assuming an increase in

cash outflows in the 1 to 28 days time bucket by 50 per

cent and 100 per cent respectively. It was assumed that

there were no changes in cash inflows under both the

scenarios. The banks were considered to be impacted

if, as a result of the stress, the mismatch or negative

gap (i.e. the cash inflow less cash outflow) in the 1 to

28 days time bucket exceeded 20 per cent of outflows.

The stress test results indicate that the SUCBs would be

significantly impacted even under the less severe stress

scenario (Chart 3.40).

Non-Banking Financial Companies

NBFCs able to withstand credit risk shocks

3.52 A stress test on credit risk for NBFC-ND-SI sector

for the period ended December 2011 was carried out

under two scenarios assuming an increase in gross NPA

by 200 per cent and 500 per cent respectively.

3.53 It was observed that, in the first scenario, CRAR

reduced marginally from 27.5 to 26.8 per cent, while

in the second scenario CRAR reduced to 24.3 per cent.

The sector, thus, remained resilient even to the more

severe stress scenario owing largely to its comfortable

CRAR position. However, the CRAR of some individual

NBFCs (accounting for around 5 per cent of total assets of

NBFC-ND-SIs), fell to below the regulatory requirement

of 15 per cent.

|