by

Deb Kusum Das1 Acknowledgements My first and foremost gratitude is for the team of young scholars who helped me in the compilation work of trade database by industry groups - Stuti Rawat wanted to learn about databases and did a commendable job of leading the creation of a trade data base by industry by mapping several thousands of tariff lines at six digit ITC (HS) codes for total manufacturing and its sub-groups at NIC 1987 and compiling for the 20 years beginning 1990-91. I can never repay my debts to her for her commitment and tireless hard work till the very last minute when she left to pursue research at National University of Singapore. Several others assisted and worked to take this forward at various stages - Pilu Chandra Das who anchored the database creation after Stuti left. Shyamaditya Singh for compiling the export-import data and creating the non-tariff barriers and Keshav Parthasarathy did a summer intern with me on trade dataset. Words cannot express my gratitude. Discussions with Gunajit Kalita helped me to derive several patterns of trade policy behavior and to understand the nuances of panel data econometrics and its applications to examining trade openness for Indian manufacturing. I thank Professor K L Krishna for his insights and comments which helped to improve the presentation of the econometric analysis. I owe special gratitude to B N Goldar and Kunal Sen for encouraging me to update and expand the trade database so that new research issues on aspects of trade liberalization can be addressed. Homagni Choudhury assisted in cross checking several aspects of trade policy statements to see if they tally with the way ITC codes have figured in various documents for tariff and non-tariff barriers- customs tariff manual, DGCI&S data of the Government of India. I owe them a deep gratitude. The estimates of total factor productivity used in the study were provided from a study by Pilu Chandra Das. I thank him for allowing me to use this series for my econometric research. Shri Arunachalaramanan and his colleagues at the RBI for believing that a short study research project on quantifying trade barriers across Indian manufacturing would be a valuable study for India’s apex monetary authorities - the Reserve Bank of India and enabling the funding of this study as a short study research grant. In particular, I would like to thank Dr Ananthaswamy, Balbir Kaur, B M Misra and others for their continued support to the project. I thank participants at RBI for comments received at both work in progress and project ending presentations. These comments have enriched the quality of the final report. Finally, to push forward further research on a Ph.D dissertation completed at the Delhi School of Economics more than a decade back were many. The inspiration I drew when Kaushik Basu asked me to contribute a chapter on “Trade Barriers in Manufacturing” on Oxford Companion to Indian Economy based on my Ph.D work and to several scholars like Rodrik and Subramanian (2005), Kunal Sen (2009) and Kotwal et al (2011) who cited estimates of trade liberalization based on my trade data base for scholarly articles to document India’s efforts at trade liberalization, egged me to push for some new evidence on “Has protection declined substantially in Indian Manufacturing?” Deb Kusum Das

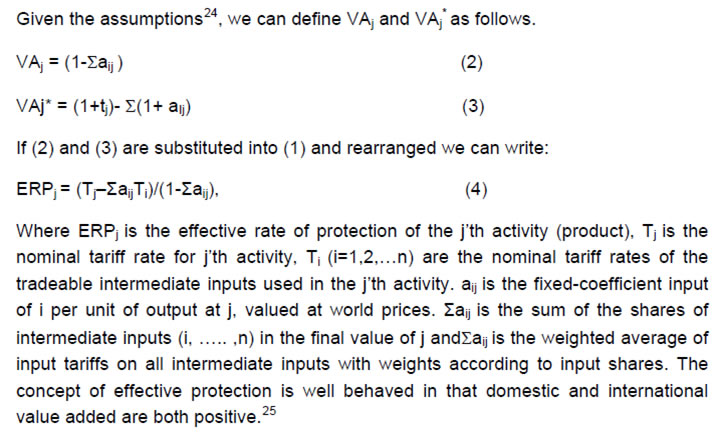

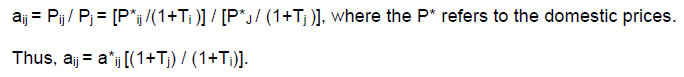

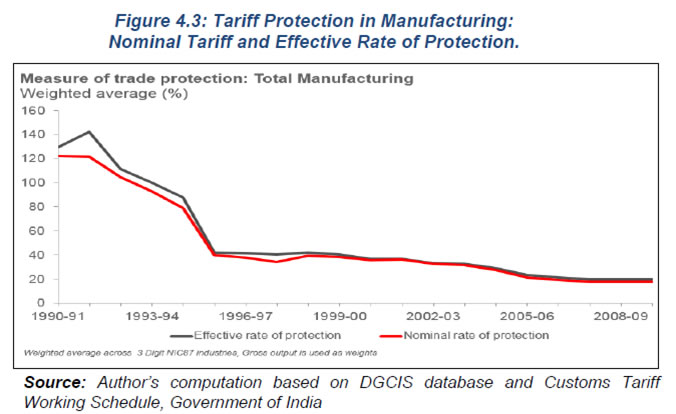

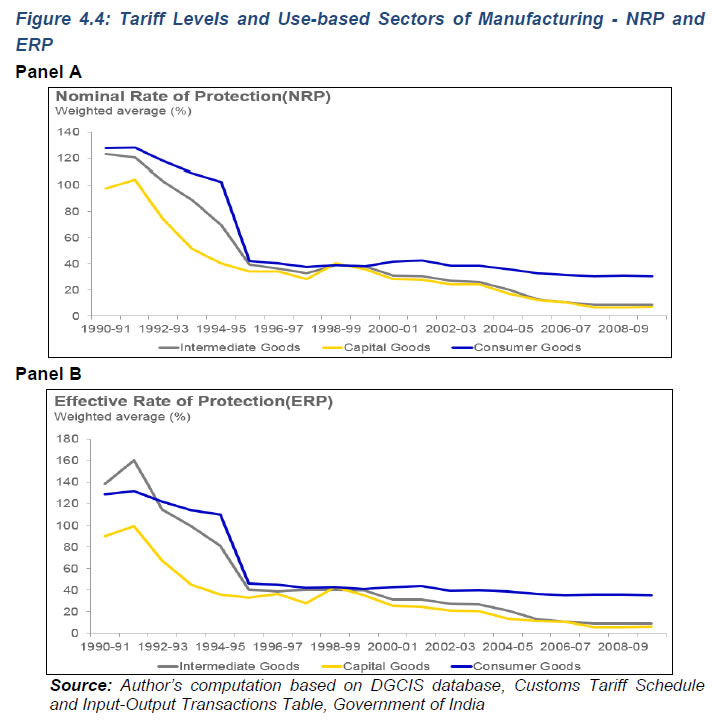

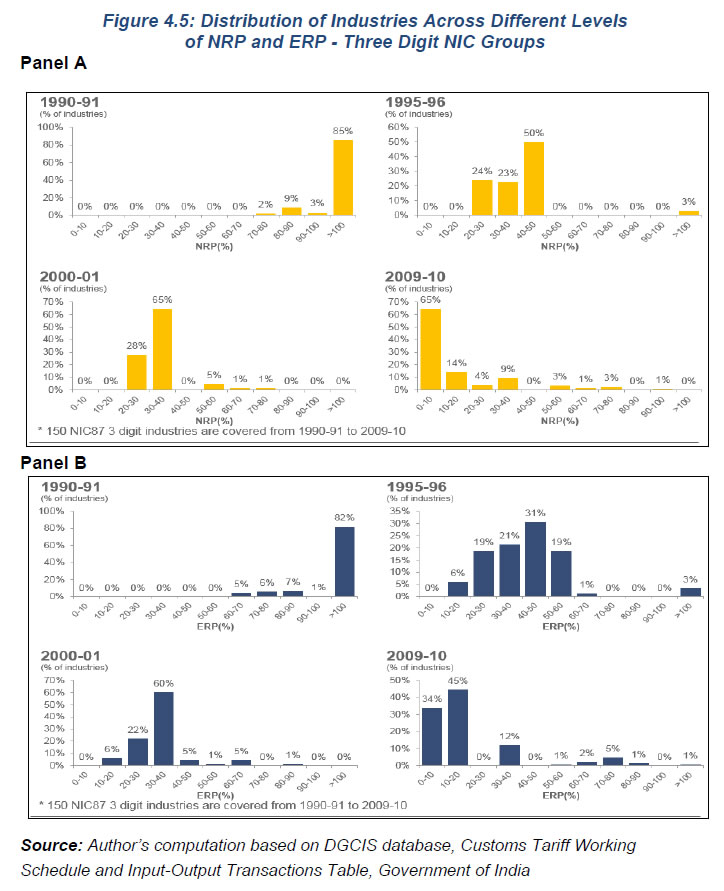

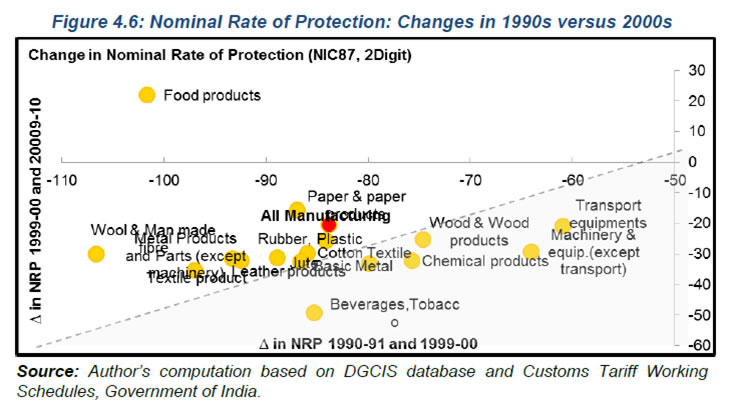

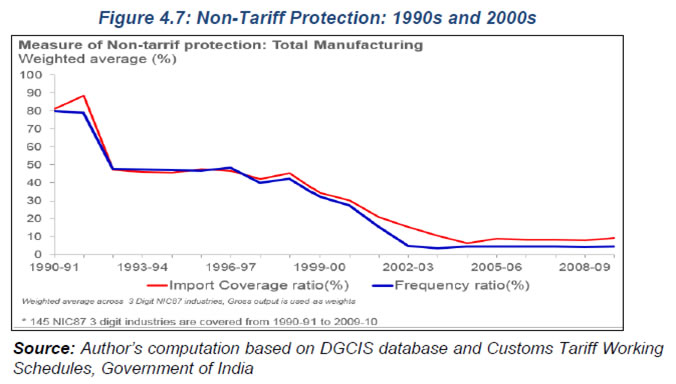

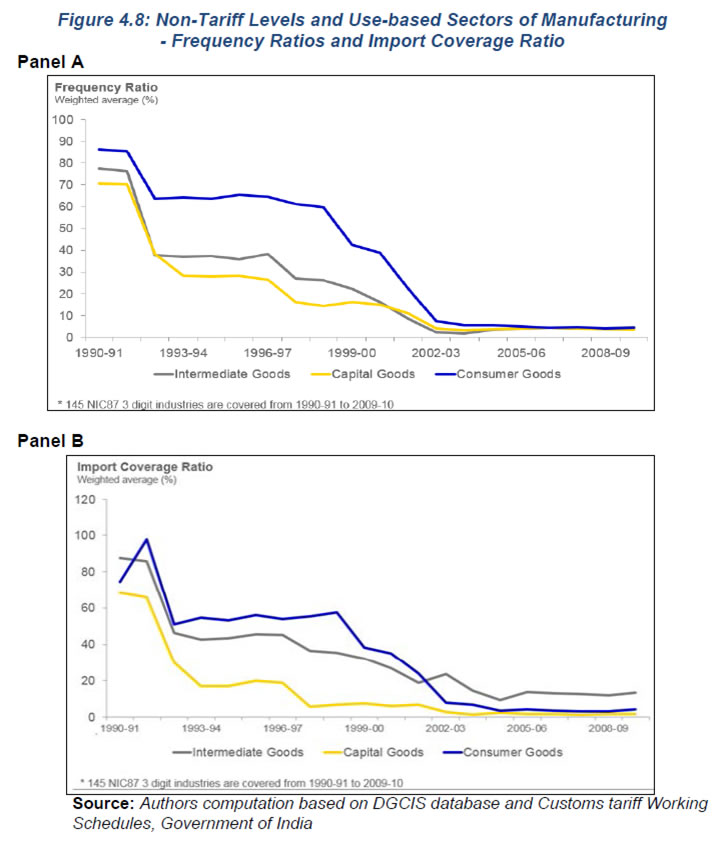

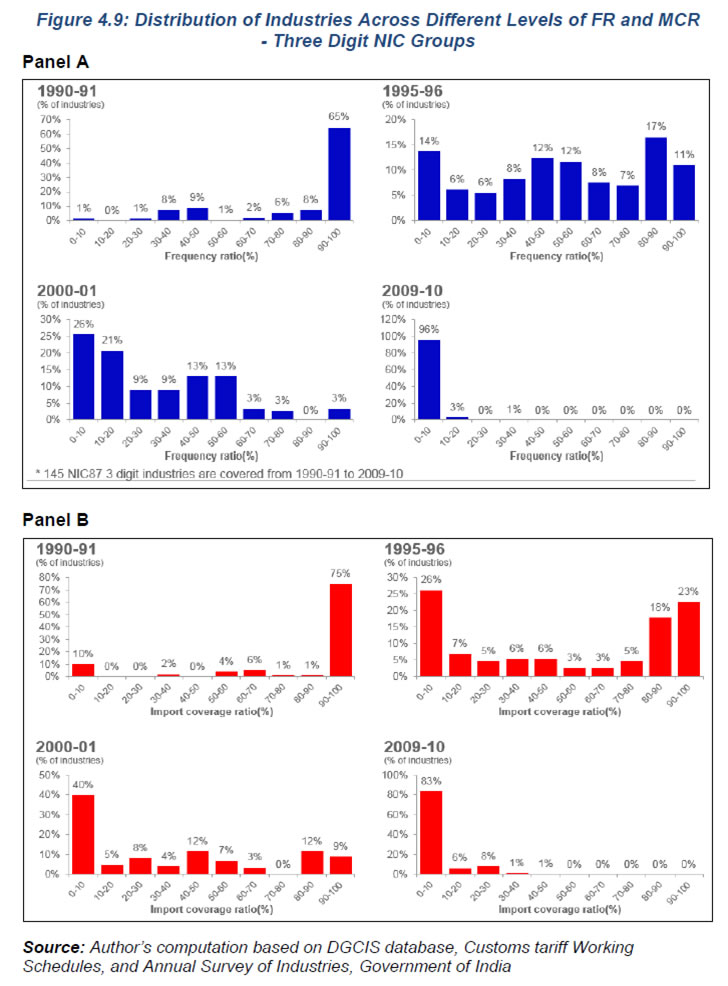

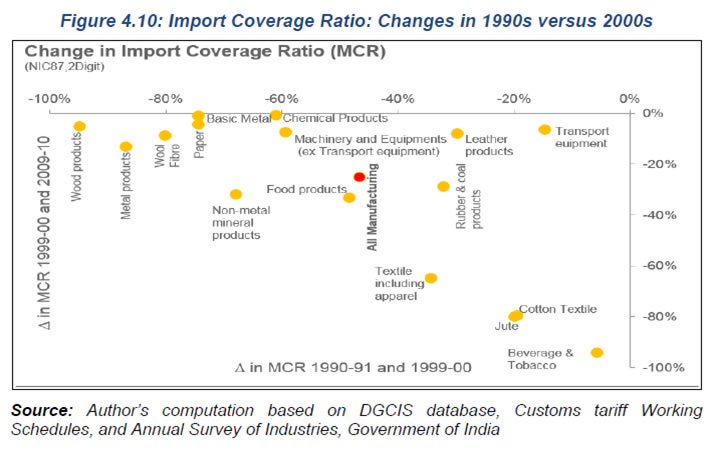

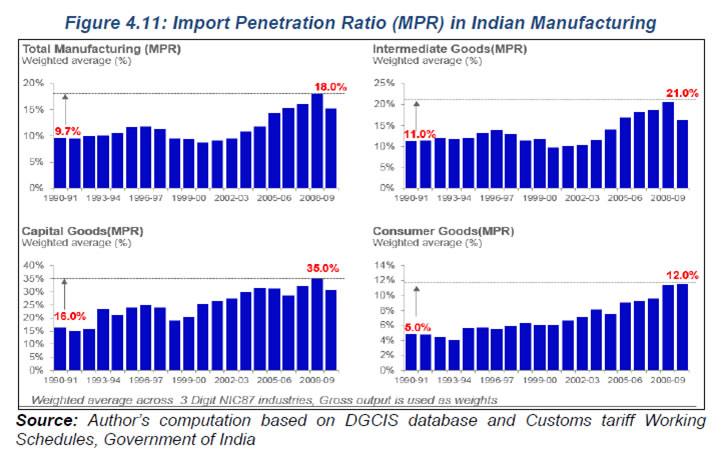

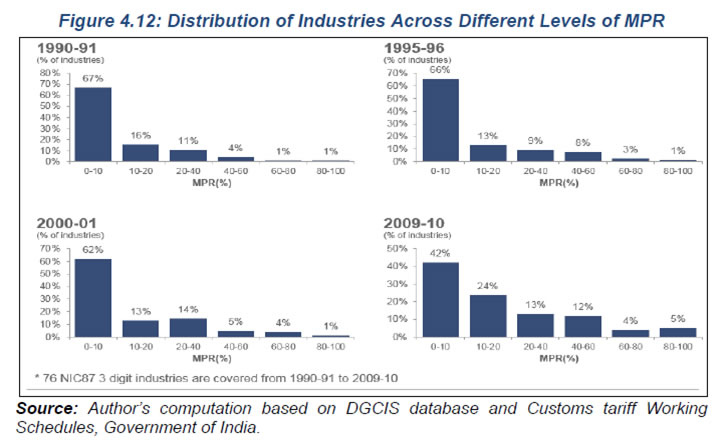

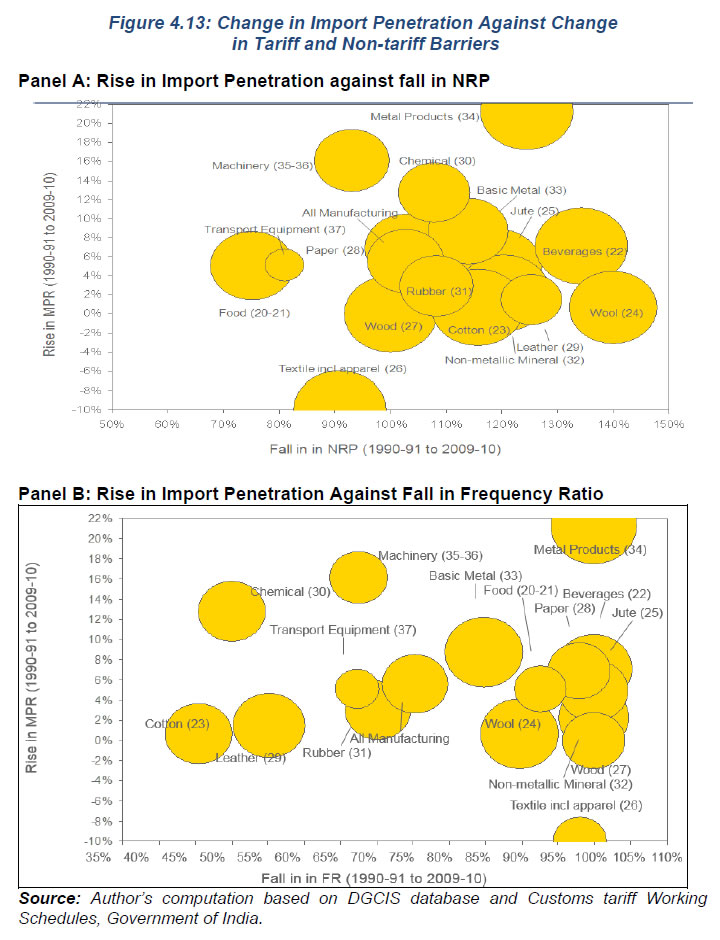

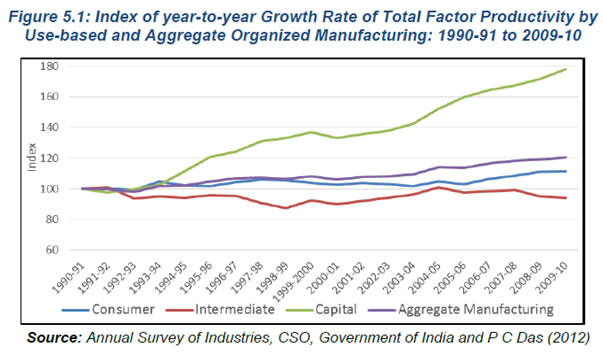

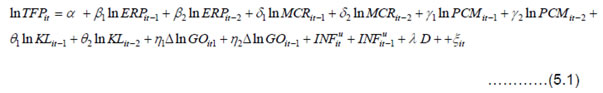

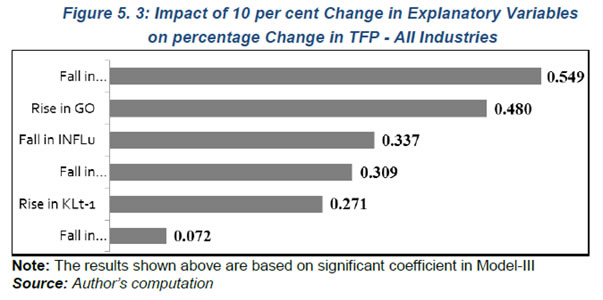

Executive Summary Trade interventions in Indian manufacturing have been of two types: tariff and non-tariff barriers (NTBs). The former remained the most pervasive form of import protection, although NTBs of various forms were often listed as the major constraint. Over the last 40 years, trade barriers in India have fallen to historically low levels, however the role of trade policy reforms in the process of India’s industrial growth and development continues to be widely debated. This study presents industry-level evidence regarding the connection between trade policy reforms and manufacturing performance. It contributes to the existing literature in several respects. The study documents the level of trade liberalization at the level of individual sectors of manufacturing using explicit measures of trade policy orientation. This is done via computation of nominal and effective rates of protection, frequency and import coverage ratios of non-tariff protection and finally imports penetration ratios to assess the joint lowering of both tariff and non-tariff protection. The analysis centers on examining both trends and pattern of trade policy reforms. The impact of trade openness on manufacturing performance is examined via a panel data econometric modeling of trade-industrial productivity linkage alongside incorporating other policies-industrial and macroeconomic environment. The coverage of the study is the organized manufacturing sector and use-based sectors of organized manufacturing and the period extends from 1990-91 to 2009-10 giving us twenty years of trade liberalization efforts. The study observes that removal of restrictions in trade - in terms of lowering of tariff barriers and dismantling of import licensing regime has been substantial since 1990-91 but gain in terms of import penetration has not been of the similar order. In particular, trade protection measured by Nominal import tariff as well as Effective rate of protection (ERP) were brought down substantially in 1990s. Non-tariff protection got almost halved by 1992-93 and become less than 10 per cent by the beginning of 2000-01. Two, Capital goods saw faster reduction in ERP as well as NTBs during 1990s compared to intermediate & consumer goods. Three, at the level of organized manufacturing the change in import penetration rates show a near doubling within 20 years from around 9.7 per cent in 1990-91 to around 18 per cent by the end of 2009-10. We have also compared the period of 1990s versus 2000s in order to understand the manner of lowering of tariff as well as non-tariff barriers. We confirm that there was a sharp fall in tariff levels as well as quantitative restrictions in the 1990s as compared to the 2000s. The periods of 2000s were more aimed at simplifying the trade procedures as well as boosting exports. The examination of the impact of trade openness as captured by various measures of trade policy reforms indicates that a decrease in tariff barrier (captured by effective rate of protection) on industrial productivity is mainly felt with one year lag and the reduction of NTBs captured by import coverage ratio has relatively smaller impact on increase in TFP. The biggest impact of rise in TFP has actually comes from improvement in domestic industrial policy. Therefore, greater internal competitive pressure brought about by reforms in industrial policy acts a spur to productivity growth. We also find a positive impact of increase in capital intensity in capital goods sector and this is mainly driven by substantial lowering of tariff rates on capital goods imports as well relaxing of import controls on machines and equipments since 1991-92. Our quantitative result reinforces not only the role of trade policy reforms but also the literature on roles of industrial as well as trade reforms as complementarities in enhancing manufacturing performance. Our findings have strong policy implications as we have already seen substantial reduction in levels of trade protection across manufacturing groups. Further, the trade policy changes have also been followed by reforms in industrial policy. However, manufacturing performance still remains far below that of other emerging countries especially China. Therefore, we need to address issues which can further magnify the benefits of trade and industrial policy reforms such as easing of supply constraints- transport bottlenecks, power shortages, erratic supply of energy (water and electricity), labor regulations etc. Appropriate policy actions on these fronts along with further easing of trading environment will make India’s manufactured goods internationally competitive.

Trade Policy and Manufacturing Performance: Exploring the Level of Trade

Openness in India’s Organized Manufacturing in the Period 1990-2010 Deb Kusum Das 1. Introduction The Trade regimes in India have remained heavily distorted by both tariff and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for more than four decades and the actual system of trade restrictions have been pervasive and highly complex. Trade policy reform in the 1990s, given its economy wide impacts, was considered as a key component of the reform process initiated in India. Such reforms were conceived to contribute to improved economic performance in the industrial sector as well as the overall economy.2 To better understand the dynamics of the manufacturing sector and its performance in India, it is important to examine the role of trade in Indian industrialization. It is now well known and documented that trade policy based on import substitution was at the core of India’s attempt at industrialization in 1947. After more than four decades of practicing of an inward looking trade policy, reforms in trade policies formed a significant part of this economic liberalization process in India. The 1980s saw changes in the external and the industrial sector in matters pertaining to licensing for scale and technology as well as quantitative restrictions on imports and tariff rates. The 1990s brought about comprehensive trade liberalization encompassing abolition of non-tariff barriers, reduction of peak tariff rates and dispersion along with devaluation of the rupee. However contrasting views have been documented regarding the impact of trade policy regime changes on Indian manufacturing.3 The manufacturing sector in India underwent a transformation from a highly regulated business environment in Nehru-Mahalanobis framework of planned industrialization to a partially de-licensed regime in the late 1980s. With the advent of reforms in 1990s, manufacturing performance registered a decline in early years; growth rate picked up but decelerated in the late 1990. Currently India’s manufacturing share still remains low compared to other developing countries especially China. Two specific points of manufacturing performance are in order - First, manufacturing productivity still remains very low despite reforms aimed at making this sector competitive (Das et al (2014)). Two, employment generation ability of the manufacturing sector has always remained a question mark. Today the issue is not only about “puzzle of jobless growth”. The creation of good jobs in Indian manufacturing is an important challenge (Kapoor 2014). Apart from issues connected to growth and employment aspect, poor performance of manufacturing in India still continues to be plagued by low technological depth due to very low R & D activities, issues of skill development and labor regulations (Manufacturing Plan - Strategies for Accelerating Growth of Manufacturing in India in the 12th Five Year Plan and Beyond, Planning Commission, Government of India). 1.1 Objective of the Study In the Indian context, there has been extensive research on assessing the levels of protection for the Indian economy. Given the complex nature of trade barriers, most studies have endorsed the adverse impact of protection on the performance of Indian industries.4 Two issues that emerge out of the prevailing studies is that – one, very few studies have attempted to quantify trade barriers by industry using outcomes of trade policy reforms- lowering of tariff and or abolishing of quantitative restriction (QR) [Das (2003) is the only study that have attempted to quantify measures of trade liberalization by select industry groups.5]. Two, though there have been numerous econometric studies trying to assess the impact of trade liberalization on Indian industry most of them use dummy variables as proxy for trade liberalization without using a quantified measure of trade policy by industries.6 Further, India’s attempt at trade liberalization in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in overall changes in the trading regime with substantial lowering of tariffs and near abolition of import control except for a few groups of industries on grounds of health, environment and defense. Further, the trade policies of 1997-98 and 2003-4 attempted to further consolidate the trade liberalizations of 1991-92. The trade regime in India was not only distorted with high tariff rates but there continued to be several exemptions as well as additional charges/surcharges at several points in time which continued to complicate the trading environment despite the lowering of peak rates of customs duty etc. These continued to remain as hurdles in the path of trade liberalization. Further, it is well known by now that both the ad hoc changes in 1980 and the changes in 1990s were mostly limited to tariff lines of intermediate and capital goods, agricultural consumer products and consumer products – durable and non-durables continue to remain with import controls and somewhat higher tariffs in relation to capital and intermediate goods. It was only after 2002-03 we find that substantial changes – tariff as well as NTBs were removed from tariff lines belonging to consumer goods. This is important and hence India’s reforms of its trade regime continued beyond 1990s. This makes it imperative to examine the level of trade liberalization beyond the 1990s into the period of 2000s, 2000-2010 which forms the core of this research. It is generally believed that industrial de-regulations on manufacturing sector along with changes in trading rules and regulations - tariffs, import controls stimulate competitive behavior amongst firms and in turn enhance industrial performance. As indicated earlier numerous studies have attempted to examine the trade- industrial performance for Indian economy. However a major limitation of many of these studies is that they have used a time dummy variable to capture the effect of reforms, which tends to pick up the effect of other changes taking place in the economy and may not properly show the effect of trade reforms. We attempted to overcome this limitation in using quantified measures of trade policy reforms as explanatory variables in our econometric exercise to discern if trade policy changes do have an impact on industrial performance? Objective of the Study is two fold -

To re-examine India’s efforts at trade liberalization for the 20 year period beginning 1990-91 at the level of manufacturing sector, especially in organized manufacturing. We will examine trends and patterns of lowering tariff as well as non-tariff barriers (QRs) at the total manufacturing as well as use-based sectors of manufacturing- intermediate, capital and consumer goods. To do this end, we compute and estimate - nominal as well as effective rate of protection, proxies for NTBs - frequency ratio as well as import coverage ratio. Finally, to assess the impact of simultaneous lowering of tariffs and non-tariff restrictions, we compute and analyze the patterns of import penetration rates. -

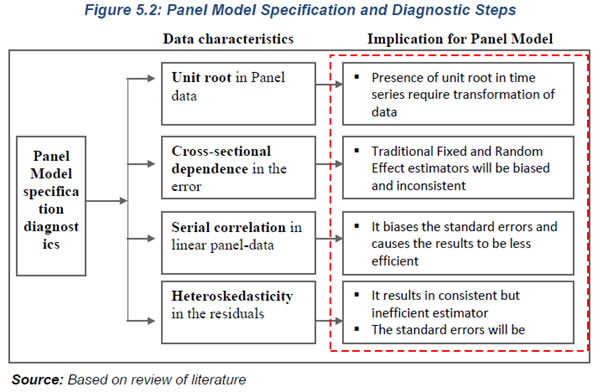

An assessment will be made of the impact of these measures on manufacturing performance for the period 1990-2010 through a quantitative framework. In particular, an econometric model based on panel data to explore the impact of trade liberalization on manufacturing indicators for the manufacturing sector in India covering the several phases of trade reforms beyond 1990-91. To assess the impact on manufacturing performance, we use variables that represent trade liberalization along with industrial policy reforms and macroeconomic business environment (including exchange rate uncertainty)7. Both the above objectives cover all sectors of organized manufacturing as well as the time period 1990-2010. The first objective is accomplished at the level of three digit industrial classifications based on NIC 1987 and the second is based on three digit industrial classification based on NIC 1998. Our reasons for using the two industrial classifications are the following- It is well known that Indian industries faced high levels of customs duties and import controls for almost four decades of inward looking development strategy of the Government of India, however when documenting levels of protection by manufacturing categories, it is very important that we acknowledge the differences in tariff rates when examining on the basis of tariff lines. Tariff lines are available at 6 or 8 digit level of disaggregation and a detailed breakdown of manufacturing groups into sub-groups as deep as three and four digit NIC allows a better documentation and examination of protection levels. NIC 1987 in our opinion has a better spread of sub-groups as compared to NIC 1998 three digit levels and hence the preference for NIC 1987. As regards, quantitative exploration through an econometric study, NIC 1987 cannot be extended further as concordance between the two classifications at three digit level is not comparable. Further, indicators of manufacturing performance like productivity, price-cost margins cannot be constructed further as no extension of NIC 1987 through mapping is possible, thereby forcing us to use NIC 1998 database for constructing our dependent variable (TFP in this case) 1.2 Sample and Time Period We compute measures of trade policy reforms- nominal and effective rates of protection (NRP and ERP), non-tariff barriers (FR and MCR) and import penetration ratio (MPR) for all sub-groups of organized manufacturing at three- digit NIC 1987. The three digit industries are covered under the following two digit heads as depicted in the annexure. In all, we have covered the entire organized manufacturing sector. Further, we have also made an attempt to document trade policy indicators by use-based sectors of organized manufacturing based on three digit sub-groups. The period of study extends from 1990-91 to 2009-10 to undertake an analysis of the impact of trade liberalization on manufacturing performance in Indian industry during the period when significant changes took place in the trade and industrial policy framework (trade policy statements of 1991-92) and consolidation of changes took place (trade policy statements of 1997-98 and 2002-03). The significance of the time period lies in the fact that though substantial reforms in trade policy happened in 1991-92, but the 2000s is important as trade policy document of 2003-04 to-2009-10 continues to simplify procedures on customs duties and lessen controls along with measures to boost exports [(Kowalski and Dihel (2009)] which address issues at India’s continued efforts at lowering protection levels in manufacturing. 1.3 Plan of the Study This study is structured in several sections. In the next section, we provide an overview of the research that has already examined the issues mentioned in the two fold objectives. We also highlight some of the major limitation of those studies so that we are put the present research in a better perspective. The methodology of the study is presented in section 3 and we outline the formulas which are used to compute the four measures of trade policy reforms. In section 4, we quantify the trade liberalization attempted so far in terms of the estimates of levels of trade barriers and outline the trends and patterns. The final section provides a detailed examination of the impact of trade reforms on manufacturing performance for the period 1990-2010. The final section concludes the study and lists avenues for future research. 2. Trade Liberalization and Indian Manufacturing - Review of Literature It is well understood by now that India’s attempt at trade liberalization was to create a trade regime devoid of import licensing as well as high rate of tariff on one hand and on the other to boost manufactured exports. Several scholarly writings have addressed the issue of trade policy changes in Indian economy (Panagariya (2004), among others). We attempt here to review the literature on trade liberalization and Indian manufacturing in two parts. First, we document the available literature on quantifying trade barriers and second, we examine the studies which have studied the impact of reforms in trade policy on Indian manufacturing. 2.1 Quantifying Trade Barriers - A Review India has had a very restrictive trade regime since the late 1950s. The major instruments of protection that have been used to regulate import demand have been an extensive import licensing system and high levels of tariffs. The economic costs of India’s trade regime have been a recurring theme in academic research [Bhagwati and Srinivasan (1978), Rao (1985), Pursell (1988)]. Further, the recommendations of official committees [Alexander (1977), Hussain (1984) and Narsimham (1984)] and policy statements have been influential in shaping the Indian thinking on trade liberalization. Starting from the early 1980s, there have been important import policy changes such as expansion of OGL list, shifting of goods from more to less restrictive lists, swifter and less administrative judgments and some reduction in the scope of canalization. In particular, there has been a relaxation of restrictions on capital and intermediate goods import, though primarily of commodities not competing with domestic production. The overall scenario that emerges from the major studies on Indian trade policies is that, the protectionist regime created a large and diversified industrial base and neglected the considerations of costs and comparative advantage, the consequence of which was the inefficient use of resources in Indian industries. There have been several studies documenting the protection accorded to Indian industry. These can be grouped as: (1) studies exploring the structure of nominal tariffs, (2) studies trying to analyze the level and structure of inter-industry protection and (3) those that attempt to quantify the extent of NTBs in Indian industry. Goldar, Narayana and Hasheem (1992) examine the pattern of tariff, statutory and realized during the 1980s at the level of broad groups and detailed product classes whereas Mehta (1999) documents the tariff rates for the 1990s by different sections and chapters of HS classification. The level and structure of inter-industry protection have been examined using both nominal tariffs and effective rate of protection [World Bank (1989), Aksoy (1991), Aksoy and Ettori (1992), Goldar and Hashim (1992), Gang and Pandey (1998) and Hashim (2001)]. Despite attempts to liberalize India’s import trade regime, the structure of import licensing has remained restrictive and complex. There have however been a few attempts to quantify NTBs according to the manufacturing sectors [Aksoy (1991), Mehta (1997), Pandey (1999), Hashim(2001), Das(2006) and Sen (2007)]. Table 2.1 highlights the studies that addressed a range of issues pertaining to the effects of the protectionist trade regime on industrial performance. | Table 2 1: Synoptic view of Studies of Import Protection in Indian Industries | | Study | Objective | Coverage | Measures | Main Findings | | World Bank (1989) | To study the level and structure of protection | Manufacturing

Sub-sectors

1986-87 | NRP and ERP based on Price Comparison | High levels of protection and inability to undertake process and product innovation | | Aksoy (1991) | To quantify the structure of import licensing regime and analyze the structure of tariffs | Input-Output Sectors

1987-88 | Nominal Tariff

& Frequency Ratio | Licensing system does not provide any additional protection. Absolute levels of tariffs are high and high tariffs on capital goods | | Aksoy and Ettori (1992) | To estimate the structure of incentives and protection | Three sectors:

Iron & Steel

Petrochemicals

Capital goods

1986-87 to

1988-89 | Nominal

Rate of Protection | High magnitude and variance of protection rates. | | Goldar and Hashim (1992) | To document the protection | Input-Output Sectors

1980-81;

1983-84;

1988-89. | NRP & ERP

[ Corden Measure] | Increase in Protection across I-O sectors; input based sectors & trade based sectors between 1980-81 to 1988-89 | | Mehta (1997) | To quantify changes in trade protection | Manufacturing sectors

1989-90

1993-94

1995-96 | NRP & ERP [Corden’s Method]

& Frequency Ratio | Significant decline in the level of protection; No QRs on more than 55%

Tariff lines. | | Gang and Pandey (1998) | To study the inter-industry structure of protection | Input-Output Sectors

1979-80

1984-85

1991-92

1996-97 | NRP & ERP

[Balassa and

Corden

Method] | Level of protection varies according to the notion of tariff rate used.

ERP levels indicate positive protection for 32 manufacturing sectors | | Pandey (1999) | To document NTB’s in Indian manufacturing | Input- Output sectors

1994-95

1996-97

1997-98 | Frequency Ratio & Tariff Equivalence

of NTB | Incidence of NTB shows a decline. The tariff equivalence calculated gives an indication of what the tariff rates should be | | Mehta (1999) | To document Tariff

and Non-Tariff

Barriers in the Indian

Economy | Sections of

and Chapters

of HS classification

1993-94 to

1998-99 | Average

Tariff Rate

& Frequency Ratio | Significant decline in average tariff rates, though the dispersion of the tariff rates has not declined. Only 28% of product lines subject to NTB by 98-99 | | Hashim (2001) | To examine the structure of tariffs and NTB’s | Input-Output

Sectors

1987-88

1992-93

1994-95

1997-98 | NRP and ERP