During 2019-20, scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) registered a robust performance characterised by improved asset quality, stronger capital and provision buffers, and return to profitability after a gap of two years. These improvements continued in H1:2020-21 even in the face of the pandemic, aided by the moratorium, the standstill in asset classification and restrictions on dividend pay-outs. While the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) remained the dominant mode of recovery, recovery rate of the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest Act, 2002 (SARFAESI) channel also improved. Going forward, with gradual rollback of policy measures, deterioration in asset quality may pose challenges, although build-up of buffers like COVID-19 provisions and capital raising from market may help alleviate the stress. 1. Introduction IV.1 In 2019-20, India’s commercial banking sector consolidated the gains achieved after the turnaround in 2018-19. Financial performance was shored up in H1:2020-21 by the moratorium and the standstill in asset classification. The overhang of stressed assets declined, and fresh slippages were reined in. With improvement in margins and recoveries of delinquent loans, the banking system turned profitable after a gap of two years. At the same time, capital buffers were strengthened, partly aided by recapitalisation of public sector banks (PSBs) and capital raising in the market. The immediate impact of lockdowns on the financial performance of commercial banks was mitigated through timely policy actions by the Reserve Bank. Going forward, although the risks to the banking sector remain tilted upwards, much hinges around the pace and spread of the economic recovery that is gradually gaining traction in H2:2020:21. IV.2 Against this background, this chapter discusses the balance sheet developments in respect of 97 scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) during 2019-20 and H1:2020-21, based on annual accounts1 of banks and off-site supervisory returns in Section 2. This is followed by an assessment of their financial performance and state of financial soundness in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Sections 5 to 11 cover issues relating to sectoral deployment of credit, ownership patterns, corporate governance practices, foreign banks’ operations in India and overseas operations of Indian banks, payment system developments, consumer protection and financial inclusion. Developments related to regional rural banks (RRBs), local area banks (LABs), small finance banks (SFBs) and payments banks (PBs) have been analysed in Sections 12 to 15 separately. The concluding section highlights the major issues emerging from the analysis and offers suggestions on the way forward. 2. Balance Sheet Analysis IV.3 The consolidated balance sheet of SCBs has grown in H1:2020-21 after a deceleration in 2019-20 on account of subdued economic activity, deleveraging of corporate balance sheets and muted business sentiment impacting credit supply (Table IV.1). On the liabilities side, slowdown in deposit growth contributed to banks’ financial weakness (Chart IV.1). The recovery in 2020-21 (so far) has been driven by investments and deposit growth in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic. | Table IV.1: Consolidated Balance Sheet of Scheduled Commercial Banks | | (At end-March) | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Item | Public Sector Banks | Private Sector Banks | Foreign Banks | Small Finance Banks # | Payments Banks | All SCBs | | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | | 1. Capital | 51,060 | 72,040 | 21,344 | 26,866 | 77,809 | 85,710 | 4,213 | 5,151 | - | 1,035 | 1,54,427 | 1,90,802 | | 2. Reserves and Surplus | 5,46,066 | 5,80,886 | 5,27,665 | 5,82,425 | 96,979 | 1,08,987 | 5,821 | 11,047 | - | -461 | 11,76,531 | 12,82,884 | | 3. Deposits | 84,86,215 | 90,48,420 | 37,70,013 | 41,59,044 | 5,81,238 | 6,84,289 | 49,178 | 82,488 | - | 855 | 1,28,86,643 | 1,39,75,095 | | 3.1. Demand Deposits | 5,52,461 | 5,71,383 | 5,17,356 | 5,47,521 | 1,71,907 | 2,17,874 | 1,955 | 2,381 | - | 8 | 12,43,679 | 13,39,167 | | 3.2. Savings Bank Deposits | 27,99,445 | 30,41,902 | 10,45,648 | 11,72,739 | 59,459 | 70,007 | 7,245 | 10,284 | - | 847 | 39,11,797 | 42,95,779 | | 3.3. Term Deposits | 51,34,309 | 54,35,134 | 22,07,008 | 24,38,784 | 3,49,872 | 3,96,408 | 39,978 | 69,823 | - | - | 77,31,167 | 83,40,149 | | 4. Borrowings | 7,61,612 | 7,09,780 | 7,75,324 | 8,27,575 | 1,51,367 | 1,28,687 | 21,367 | 30,004 | - | - | 17,09,670 | 16,96,046 | | 5. Other Liabilities and Provisions | 3,18,274 | 3,71,893 | 2,03,591 | 2,36,229 | 1,48,982 | 2,57,632 | 2,928 | 4,078 | - | 216 | 6,73,775 | 8,70,048 | | Total Liabilities/Assets | 1,01,63,226 | 1,07,83,018 | 52,97,937 | 58,32,139 | 10,56,375 | 12,65,304 | 83,508 | 1,32,768 | - | 1,645 | 1,66,01,045 | 1,80,14,875 | | 1. Cash and Balances with RBI | 4,55,974 | 4,36,736 | 2,06,654 | 2,72,616 | 33,660 | 55,048 | 2,328 | 5,058 | - | 33 | 6,98,616 | 7,69,492 | | 2. Balances with Banks and Money at Call and Short Notice | 3,93,270 | 4,66,615 | 1,75,076 | 2,12,324 | 91,095 | 95,658 | 4,054 | 8,701 | - | 455 | 6,63,494 | 7,83,753 | | 3. Investments | 27,02,033 | 29,40,636 | 12,22,045 | 12,93,031 | 3,83,433 | 4,31,277 | 14,953 | 24,203 | - | 694 | 43,22,464 | 46,89,842 | | 3.1 In Government Securities (a+b) | 21,98,041 | 24,09,182 | 9,51,273 | 10,66,313 | 3,19,567 | 3,84,109 | 11,633 | 20,748 | - | 694 | 34,80,513 | 38,81,046 | | a) In India | 21,67,070 | 23,71,783 | 9,32,574 | 10,57,074 | 3,05,764 | 3,62,547 | 11,633 | 20,748 | - | 694 | 34,17,040 | 38,12,845 | | b) Outside India | 30,970 | 37,399 | 18,699 | 9,240 | 13,803 | 21,562 | - | - | - | - | 63,473 | 68,201 | | 3.2 Other Approved Securities | 157 | 102 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 157 | 102 | | 3.3 Non-approved Securities | 5,03,835 | 5,31,352 | 2,70,772 | 2,26,718 | 63,866 | 47,168 | 3,320 | 3,455 | - | - | 8,41,793 | 8,08,694 | | 4. Loans and Advances | 58,92,667 | 61,58,112 | 33,27,328 | 36,25,154 | 3,96,726 | 4,28,072 | 59,461 | 90,576 | - | - | 96,76,183 | 1,03,01,914 | | 4.1 Bills Purchased and Discounted | 1,66,336 | 1,60,977 | 1,17,234 | 1,25,078 | 76,192 | 61,864 | 4 | 37 | - | - | 3,59,767 | 3,47,955 | | 4.2 Cash Credits, Overdrafts, etc. | 24,71,666 | 24,16,408 | 9,45,461 | 9,83,165 | 1,79,764 | 2,05,130 | 5,433 | 6,872 | - | - | 36,02,323 | 36,11,575 | | 4.3 Term Loans | 32,54,665 | 35,80,727 | 22,64,633 | 25,16,912 | 1,40,770 | 1,61,078 | 54,024 | 83,668 | - | - | 57,14,093 | 63,42,385 | | 5. Fixed Assets | 1,07,318 | 1,06,507 | 36,142 | 38,243 | 4,426 | 4,129 | 1,251 | 1,649 | - | 200 | 1,49,137 | 1,50,728 | | 6. Other Assets | 6,11,963 | 6,74,412 | 3,30,693 | 3,90,770 | 1,47,036 | 2,51,120 | 1,461 | 2,580 | - | 263 | 10,91,153 | 13,19,146 | Notes: 1. -: Nil/negligible.

2. #: Data pertain to seven scheduled SFBs at end-March 2019 and 10 scheduled SFBs at end-March 2020.

3. Components may not add up to their respective totals due to rounding-off numbers to ₹ crore.

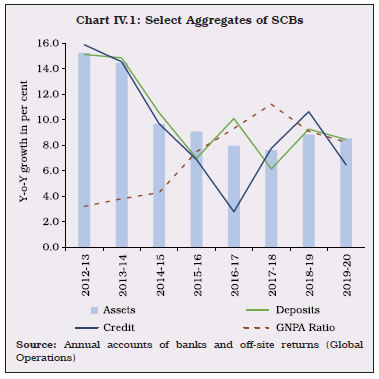

4. Detailed bank-wise data on annual accounts are collated and published in Statistical Tables Relating to Banks in India, available at https://www.dbie.rbi.org.in.

Source: Annual accounts of respective banks. |

2.1 Liabilities IV.4 SCBs’ deposit growth remained elevated throughout the first three quarters of 2019-20 relative to the period since September 2017 (Chart IV.2a). During the last quarter, i.e., January-March 2020, however, deposit growth – especially in private sector banks (PVBs) – decelerated. Currency with public surged in response to the COVID-19 induced dash for cash while solvency issues related to a private sector bank also brought about some reassignment of deposits. IV.5 During 2020-21 so far, deposits with PSBs grew at a higher pace than usual, partly reflecting perception of their safe haven status (Chart IV.2b). IV.6 Term deposits – contributing almost 60 per cent of total deposits – moderated, reflecting the easing of interest rates and the lure of returns on competing asset classes. Term deposit growth of PVBs decelerated sharply even as it quadrupled in PSBs (Chart IV.3a). Foreign banks aggressively raised low-cost current and saving account (CASA) deposits, although their share in total deposits is low (Chart IV.3b). IV.7 Subdued credit growth and relatively robust deposit growth for most part of the year resulted in a decline in borrowing requirements of banks, except for PVBs (Chart IV.4).

2.2 Assets IV.8 After a gap of two consecutive years, SCBs’ loan growth decelerated in 2019-20, reflecting both risk aversion and tepid demand. During the current financial year so far, this was accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The loan book of PVBs was affected disproportionately relative to their counterparts on asset quality concerns and higher provisioning requirements. Credit expansion was at a higher pace among PSBs during March, June and September, 2020 quarters, after three consecutive quarters of deceleration (Chart IV.5). IV.9 Another positive development was the robust credit growth in rural areas. Although the share of rural credit in the total has been hovering between 8 and 9 per cent, its growth surpassed that of other categories in 2019-20, after a gap of four years. While the share of PSBs in rural credit has gradually fallen, PVBs2 have been making inroads (Chart IV.6a and b).

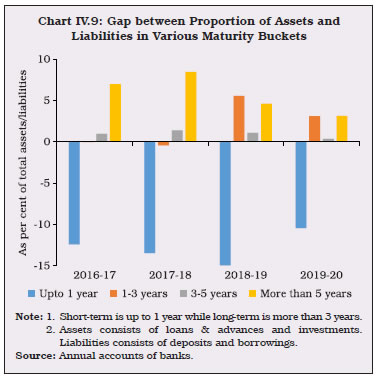

IV.10 The credit-GDP ratio declined consistently throughout 2010s, partly reflecting availability of alternate avenues to raise resources. During 2019-20, however, the ratio declined even further and the incremental credit to GDP ratio also ebbed (Chart IV.7a). The outstanding credit-deposit (C-D) ratio declined across all bank groups (Chart IV.7b). IV.11 Muted credit offtake prompted PSBs to lean in favour of investments. Risk-free liquid statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) securities were their instruments of choice amidst the prevailing uncertainties. On the other hand, investment portfolio of PVBs and FBs decelerated due to profit booking in their trading books as yield on G-Secs softened significantly during the course of the year (Chart IV.8a).  IV.12 Till end-August 2020, banks were permitted to exceed the limit of 25 per cent of total investments under the held to maturity (HTM) category, provided the excess comprises only of SLR securities and total SLR securities held in the HTM category are not more than 19.5 per cent of net demand and time liabilities (NDTL). With the headroom available for PSBs and PVBs for further investment in SLR securities under the HTM category getting exhausted (Chart IV.8b) and in view of heavy government borrowing programme for 2020-21, the 19.5 per cent limit was raised to 22 per cent of NDTL up to March 31, 2022, for securities acquired between September 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021. 2.3 Flow of Funds to the Commercial Sector IV.13 Subdued credit demand conditions were reflected in a sharp moderation in flow of credit to the commercial sector in 2019-20, from both bank and non-bank sources. The moderation in non-bank funding was lower as compared with bank funding. Corporates raised higher resources from foreign sources such as foreign direct investment (FDI), external commercial borrowing (ECB) and foreign currency convertible bonds (FCCBs). Rationalisation of ECB guidelines, prudent and tighter single-group exposure norms, low interest rates in origin countries and the relatively stable exchange rate created an enabling environment to raise more resources from foreign sources. Within domestic non-bank sources, acceleration in resources raised from the capital market – public and rights issues as well as private placements – coupled with the investment of Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) in corporate debt provided a silver lining (Table IV.2). IV.14 The flow of funds to commercial sector has been higher during 2020-21 so far. Flows from banks, domestic non-bank sources – notably private placements; commercial paper (CP) issuances; and credit by housing finance companies (HFCs) – have picked up, compensating for lower flows from foreign sources like ECB/FCCB and short-term credit from abroad (Table IV.2). 2.4 Maturity Profile of Assets and Liabilities IV.15 Asset-liability management (ALM) profiles have direct implications for liquidity and profitability of banks. Rate Sensitive Assets (RSAs) and Rate Sensitive Liabilities (RSLs) directly impact banks’ net interest income. The decision to hold a positive (RSAs > RSLs) or negative gap (RSLs > RSAs) depends on a bank’s expectations on interest rates and its overall business strategy. In an environment of declining interest rates during 2019-20, the negative gap in the maturity bucket of up to one year and positive gap in higher maturity buckets moderated (Chart IV.9). | Table IV.2: Trends in Flow of Financial Resources to Commercial Sector from Banks and Non-banks | | (₹ crore) | | | April to March | April 1 to December 4 | | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | | A. Adjusted Non-food Bank Credit (NFC) | 4,95,224 | 9,16,109 | 12,29,977 | 5,81,209 | 73,792 | 89,556 | | | (33.6) | (42.8) | (52.3) | (40.2) | (12.2) | (14.4) | | i) Non-food credit | 3,88,247 | 7,95,897 | 11,46,677 | 5,88,985 | 79,907 | 89,526 | | of which: petroleum and fertilizer credit | 13,283 | 2,724 | 7,463 | 21,721 | -16,622 | -27,168@ | | ii) Non-SLR investment by SCBs | 1,06,977 | 1,20,212 | 83,301 | -7,775 | -6,116 | 30 | | B. Flow from Non-banks (B1+B2) | 9,79,207 | 12,24,042 | 11,22,424 | 8,64,615 | 5,32,770 | 5,32,957 | | | (66.4) | (57.2) | (47.7) | (59.8) | (87.8) | (85.6) | | B1. Domestic Sources | 7,03,377 | 8,85,589 | 7,35,678 | 3,21,100 | 2,26,811 | 3,26,773 | | | (47.7) | (41.4) | (31.3) | (22.2) | (37.4) | (52.5) | | 1 Public & rights issues by non-financial entities | 15,503 | 43,826 | 10,565 | 63,689 | 59,281 | 27,571 $ | | 2 Gross private placements by non-financial entities | 2,00,243 | 1,46,176 | 1,55,133 | 2,37,062 | 1,19,442 | 1,79,641 $ | | 3 Net issuance of CPs subscribed to by non-banks | 86,894 | -25,377 | 1,36,089 | -1,52,722 | -33,041 | 53,759 $ | | 4 Net credit by housing finance companies | 1,37,390 | 2,19,840 | 1,65,893 | 8,573 | -8,852 | 51,197 @ | | 5 Total accommodation by four RBI-regulated AIFIs - NABARD, NHB, SIDBI & EXIM Bank | 46,939 | 95,084 | 1,11,984 | 82,160 | -1,738 | -12,725 @ | | 6 Systemically important non-deposit taking NBFCs and deposit taking NBFCs (net of bank credit) | 1,88,748 | 3,68,243 | 1,26,004 | 13,572 | 46,758 | 2,937 & | | 7 LIC's net investment in corporate debt, infrastructure and social sector | 27,661 | 37,797 | 30,011 | 68,766 | 44,962 | 24,393 $ | | B2. Foreign Sources | 2,75,829 | 3,38,454 | 3,86,746 | 5,43,515 | 3,05,959 | 2,06,185 | | | (18.7) | (15.8) | (16.4) | (37.6) | (50.4) | (33.1) | | 1 External commercial borrowings / FCCBs | -50,928 | -5,129 | 69,629 | 1,54,263 | 70,820 | -37,178 @ | | 2 ADR/GDR issues excluding banks and financial institutions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 @ | | 3 Short-term credit from abroad | 43,465 | 89,606 | 15,184 | -7,704 | 13,841 | -1,488 & | | 4 Foreign direct investment to India | 2,83,292 | 2,53,977 | 3,01,932 | 3,96,955 | 2,21,299 | 2,44,851 @ | | C. Total Flow of Resources (A+B) | 14,74,431 | 21,40,151 | 23,52,401 | 14,45,824 | 6,06,562 | 6,22,513 | | | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | Notes: 1. &: Up to June 2020 @: Up to October 2020 $: Up to November 2020.

2. There was a rights issue of partly paid-up shares of ₹53,124 crore by Reliance Industries Limited in June 2020, of which 25 per cent (₹13,281 crore) has been paid at the time of subscription and the balance 25 per cent and 50 per cent shall be paid in May 2021 and November 2021, respectively.

3. Figures in the parentheses represent share in total flows.

Source: RBI, SEBI, BSE, NSE, Merchant Banks, LIC and NHB. | IV.16 While liabilities like deposits and borrowings in the maturity bucket of up to one year declined, assets – specifically, investments – picked up, led by PSBs and PVBs. On the other hand, borrowings and investments in the maturity bucket of over five years dipped. At the same time, deposits and loans and advances edged up. FBs continued to focus mainly on short-term borrowings and investments (Table IV.3).

| Table IV.3: Bank Group-wise Maturity Profile of Select Liabilities/Assets | | (As at end-March) | | (Per cent to total under each item) | | Liabilities/Assets | PSBs | PVBs | FBs | SFBs | PBs | All SCBs | | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | | I. Deposits | | | | | | | | | | | | | | a) Up to 1 year | 43.6 | 40.4 | 42.9 | 38.1 | 64.2 | 63.9 | 59.6 | 59.6 | - | 10.0 | 44.4 | 40.9 | | b) Over 1 year and up to 3 years | 22.4 | 22.8 | 26.8 | 28.1 | 28.6 | 28.3 | 36.7 | 37.5 | - | 90.0 | 24.0 | 24.8 | | c) Over 3 years and up to 5 years | 10.7 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | - | - | 10.2 | 9.5 | | d) Over 5 years | 23.3 | 26.6 | 20.9 | 25.3 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 3.1 | 2.2 | - | - | 21.5 | 24.7 | | II. Borrowings | | | | | | | | | | | | | | a) Up to 1 year | 61.6 | 49.7 | 47.9 | 51.5 | 87.5 | 83.9 | 40.0 | 41.1 | - | - | 57.4 | 53.0 | | b) Over 1 year and up to 3 years | 14.1 | 27.6 | 19.9 | 24.4 | 8.1 | 9.8 | 44.9 | 44.0 | - | - | 16.5 | 25.0 | | c) Over 3 years and up to 5 years | 8.3 | 13.0 | 14.1 | 11.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 10.9 | 11.3 | - | - | 10.4 | 11.3 | | d) Over 5 years | 16.0 | 9.7 | 18.1 | 12.9 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.6 | - | - | 15.6 | 10.7 | | III. Loans and Advances | | | | | | | | | | | | | | a) Up to 1 year | 25.7 | 25.2 | 31.4 | 32.3 | 57.9 | 61.4 | 44.1 | 38.1 | - | - | 29.1 | 29.3 | | b) Over 1 year and up to 3 years | 41.6 | 40.3 | 34.0 | 33.6 | 22.1 | 19.3 | 34.7 | 42.4 | - | - | 38.1 | 37.1 | | c) Over 3 years and up to 5 years | 12.4 | 11.0 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 9.6 | 9.0 | - | - | 12.4 | 11.4 | | d) Over 5 years | 20.4 | 23.5 | 21.6 | 21.5 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 10.4 | - | - | 20.4 | 22.2 | | IV. Investments | | | | | | | | | | | | | | a) Up to 1 year | 17.9 | 22.3 | 51.7 | 54.3 | 82.6 | 82.5 | 66.3 | 59.0 | - | 100.0 | 33.3 | 36.8 | | b) Over 1 year and up to 3 years | 13.5 | 12.9 | 16.5 | 15.1 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 20.3 | 26.3 | - | - | 14.2 | 13.4 | | c) Over 3 years and up to 5 years | 13.5 | 10.7 | 8.2 | 6.8 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 3.1 | - | - | 11.0 | 8.8 | | d) Over 5 years | 55.1 | 54.1 | 23.6 | 23.8 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 12.1 | 11.6 | - | - | 41.5 | 41.0 | Note: The sum of components may not add up to 100 due to rounding off.

Source: Annual accounts of banks. | 2.5 International Liabilities and Assets IV.17 During 2019-20, total international liabilities of banks located in India declined due to a drop in short-term borrowings from abroad. Divestment by non-residents in banks, particularly PVBs, also contributed to this decline (Appendix Table IV.9). On the other hand, international assets of banks rebounded from a decline in the previous year, largely driven by an upsurge in NOSTRO balances and placements abroad. However, claims arising out of outstanding export bills sharply declined due to slackening of international trade (Appendix Table IV.10). This resulted in an uptick in the ratio of international claims to international liabilities. The ratio of international liabilities of banks to India’s total external debt declined due to an increase in external debt during the year (Chart IV.10). IV.18 The consolidated international claims of banks declined across both short-term and long-term maturities and shifted away from the non-financial private sector and banks towards non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) (Appendix Table IV.11). Consolidated international claims of banks also underwent geographical changes favouring Germany, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) at the cost of Hong Kong, the United Kingdom (U.K.) and the United States (U.S.) (Appendix Table IV.12). 2.6 Off-balance Sheet Operations IV.19 During 2019-20, off-balance sheet liabilities of PVBs and FBs decelerated, while those of PSBs contracted, suggesting prudent behaviour in the face of elevated credit risk (Chart IV.11; Appendix Table IV.2). At end-March 2020, foreign banks’ contingent liabilities were as high as 10 times their balance sheet assets, while PVBs (1.2 times) and PSBs (0.31 times) had relatively lower off-balance sheet exposures. 3. Financial Performance IV.20 Net profits of SCBs turned around in 2019-20 after losses in two consecutive years (Table IV.4). Although PSBs incurred losses for the fifth year in a row, the amount of losses shrank. PBs could not break even as they incurred high initial capital expenditure and wage bills. | Table IV.4: Trends in Income and Expenditure of Scheduled Commercial Banks | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Item | Public Sector Banks | Private Sector Banks | Foreign Banks | Small Finance Banks# | Payments Banks | All SCBs | | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | | 1. Income | 7,75,331 | 8,34,320 | 4,67,058 | 5,46,041 | 69,901 | 83,223 | 10,898 | 19,219 | - | 55 | 13,23,188 | 14,82,858 | | | (0.03) | (7.6) | (25.5) | (16.9) | (9.8) | (19.1) | (62.7) | (76.4) | | | (8.7) | (12.1) | | a) Interest Income | 6,81,575 | 7,16,203 | 3,93,637 | 4,48,566 | 55,569 | 66,673 | 9,682 | 16,948 | - | 46 | 11,40,463 | 12,48,435 | | | (3.2) | (5.1) | (29.0) | (14.0) | (10.0) | (20.0) | (65.4) | (75.0) | | | (11.6) | (9.5) | | b) Other Income | 93,755 | 1,18,117 | 73,422 | 97,476 | 14,332 | 16,550 | 1,216 | 2,271 | - | 9 | 1,82,725 | 2,34,422 | | | (-18.3) | (26.0) | (9.9) | (32.8) | (8.9) | (15.5) | (43.9) | (86.7) | | | (-6.6) | (28.3) | | 2. Expenditure | 8,41,939 | 8,60,335 | 4,39,437 | 5,26,930 | 55,393 | 67,043 | 9,816 | 17,251 | - | 389 | 13,46,585 | 14,71,947 | | | (-2.2) | (2.2) | (33.0) | (19.9) | (4.9) | (21.0) | (53.3) | (75.7) | | | (7.7) | (9.3) | | a) Interest Expended | 4,50,614 | 4,68,005 | 2,31,257 | 2,58,038 | 24,476 | 28,810 | 4,535 | 7,928 | - | 14 | 7,10,881 | 7,62,794 | | | (-1.0) | (3.9) | (32.7) | (11.6) | (14.3) | (17.7) | (70.7) | (74.8) | | | (8.8) | (7.3) | | b) Operating Expenses | 1,75,114 | 1,91,925 | 1,09,276 | 1,26,320 | 18,697 | 21,584 | 4,200 | 7,152 | - | 488 | 3,07,287 | 3,47,469 | | | (6.6) | (9.6) | (26.3) | (15.6) | (3.8) | (15.4) | (52.8) | (70.3) | | | (13.2) | (13.1) | | Of which : Wage Bill | 1,01,503 | 1,15,044 | 39,202 | 47,357 | 6,720 | 7,878 | 2,127 | 3,811 | - | 264 | 1,49,551 | 1,74,354 | | | (10.6) | (13.3) | (21.5) | (20.8) | (-2.3) | (17.2) | (36.3) | (79.2) | | | (12.9) | (16.6) | | c) Provision and Contingencies | 2,16,211 | 2,00,405 | 98,905 | 1,42,572 | 12,220 | 16,648 | 1,081 | 2,171 | - | -112 | 3,28,417 | 3,61,685 | | | (-10.3) | (-7.3) | (42.1) | (44.2) | (- 8.7) | (36.2) | (8.4) | (100.8) | | | (1.0) | (10.1) | | 3. Operating Profit | 1,49,603 | 1,74,390 | 1,26,526 | 1,61,684 | 26,728 | 32,829 | 2,163 | 4,139 | - | -446 | 3,05,019 | 3,72,595 | | | (-3.9) | (16.6) | (13.6) | (27.8) | (10.3) | (22.8) | (67.1) | (91.4) | | | (4.2) | (22.2) | | 4. Net Profit | -66,608 | -26,015 | 27,621 | 19,111 | 14,508 | 16,180 | 1,082 | 1,968 | - | -334 | -23,397 | 10,911 | | | | | (- 33.9) | (- 30.8) | (33.7) | (11.5) | (264.4) | (81.9) | | | | | | 5. Net Interest Income (NII) (1a-2a) | 2,30,962 | 2,48,198 | 1,62,380 | 1,90,528 | 31,093 | 37,863 | 5,147 | 9,020 | - | 32 | 4,29,581 | 4,85,641 | | | (12.6) | (7.5) | (23.9) | (17.3) | (6.9) | (21.8) | (61.0) | (75.3) | | | (16.6) | (13.0) | | 6. Net Interest Margin (NIM) | 2.33 | 2.37 | 3.26 | 3.42 | 3.23 | 3.26 | 7.62 | 8.34 | - | 1.95 | 2.7 | 2.8 | Notes: 1. #: Data pertain to seven scheduled SFBs at end-March 2019 and 10 scheduled SFBs at end-March 2020.

2. NIM has been defined as NII as percentage of average assets.

3. Figures in parentheses refer to per cent variation over the previous year.

4. Percentage variations could be slightly different as absolute numbers have been rounded off to ₹ crore.

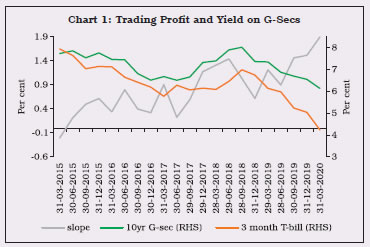

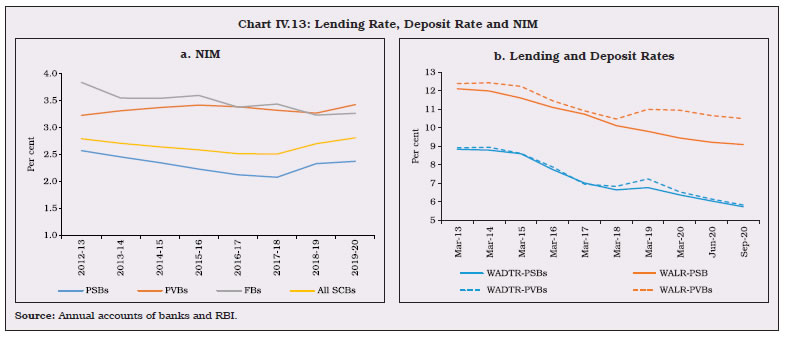

Source: Annual accounts of respective banks. | IV.21 The improvement in financial performance also reflected an increase in trading income on profit booking in the light of favourable yield movements (Box IV.1). IV.22 In line with the increasing share of PVBs in banking assets, their share in operating profits also increased to 43.4 per cent in 2019-20 at the cost of PSBs (Chart IV.12a and b). IV.23 Both interest income and interest expended by banks decelerated; however, banks managed to register higher net interest margin (NIM) with the growth in interest income. The gap between NIM of PVBs and PSBs enlarged as the former managed to lend at comparatively higher rates while reducing their deposit rates (Chart IV.13a and b). Box IV.1: Impact of Movements in G-Sec Yield on Bank Profitability A decline in G-Sec yields may prompt banks to book profits on their trading books. Higher yields and a steep yield curve are generally associated with higher NIMs (Alessandri and Nelson, 2015; Borio et al, 2015; Claessens et al, 2018). The level and slope of the yield curve have been found to affect NIM and trading income in the opposite direction, which is consistent with banks hedging interest rate risk through derivatives (Alessandri and Nelson, 2015; Borio et al, 2015). The net effect of these countervailing factors is not obvious. In the Indian context, yield on long-term government securities and short-term rates have sharply fallen in recent quarters, while the slope of the yield curve (i.e., the difference between yield on 10-year G-Sec and three-month T-Bills) has steepened (Chart 1). Using quarterly panel data of public and private sector banks for the period March 2015 to March 2020 three variations of a fixed effects model were estimated (Table 1). Controlling for bank-specific variables and macro-variables, the yield on 10-year G-Secs and the slope of the yield curve were found to have a significant and negative impact on trading profit (Col.4). This impact was strong enough to pull down total profitability (RoA) of banks (Col. 3), notwithstanding the uncertain impact on interest margins (Col. 2). The negative sign on the slope coefficient points to hedging activity of banks across the maturity spectrum.

| Table 1: Yield and Profitability: Fixed Effects Model | | Column (1) | Column (2) | Column (3) | Column (4) | | Dependent Variable: NIM | Dependent Variable: RoA | Dependent Variable: Trading profit to assets ratio | | Dependent variable (-1) | 0.375*** | 0.423*** | 0.122** | | | (0.101) | (0.046) | (0.051) | | 10-year G-Sec yield | - 0.176 | -7.142*** | - 0.044*** | | | (0.275) | (2.38) | (.004) | | Slope | - 0.009 | -3.772*** | -0.028*** | | | (0.111) | (1.071) | (0.005) | | Slope (-1) | - 0.085 | -2.613*** | -0.005 | | | (0.097) | (1.006) | (0.006) | | GNPA | - 0.016*** | -.093*** | - | | | (0.005) | (0.032) | | | CASA | 0.012*** | - | - | | | (0.003) | | | | Cost to Income ratio | -0.005 | - 0.028*** | - | | | (0.003) | (0.006) | | | Spread | 0.398*** | - | - | | | (0.056) | | | | Liquid assets to Total Assets | -0.005** | -0.002 | - | | | (0.002) | (0.012) | | | IIP | 0.004 | 0.080*** | - | | | (0.003) | (0.026) | | | Diversification | -0.001** | 0.006*** | - | | | (0.0005) | (0.002) | | | Log (assets) | 0.363 | 0.832 | - | | | (0.282) | (0.673) | | | Tier I Leverage ratio | - | - | 0.0003*** | | | | | (0.00002) | | Constant | 4.235*** | 62.537 | 0.395*** | | | (3.487) | (20.94) | (0.030) | | R2 (overall) | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.34 | | No. of observations | 818 | 814 | 656 | | Bank Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | | Time Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Notes: 1. Figures in parentheses refer to robust standard errors.

2. *p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01 | Reference: Alessandri, P. and B. D. Nelson (2015). Simple Banking: Profitability and the Yield Curve. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 47(1), 143–175. Borio, C., L. Gambacorta, and B. Hofmann (2017). The Influence of Monetary Policy on Bank Profitability. International Finance, 20(1):48-63. Claessens, S, N. Coleman and M. Donnelly (2018). “Low- For-Long” Interest Rates and Banks’ Interest Margins and Profitability: Cross-country Evidence. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 35 (2018) 1–16. Verma, R. and S. Herwadkar (2020). Interest Rate Movements and Bank Profitability: An Indian Experience, mimeo. |

IV.24 Banks’ spreads increased, with SFBs commanding the highest spread followed by FBs, PVBs and PSBs in that order (Table IV.5). SFBs – which characteristically have a larger share of microfinance portfolio than peers – face higher cost of deposits and borrowings. This was, however, more than compensated by higher lending rates. IV.25 Provisions – especially those of PVBs – accelerated on account of higher NPAs as well as to meet regulatory requirements post-loan moratorium provided as COVID-19 relief measure. Although banks are required to make general provisions of not less than 10 per cent of the total outstanding on accounts that were in default as on February 29, 2020 and where moratorium / interest deferment and the consequent asset classification benefit was extended, it was allowed to be spread over Q4:2019-20 and Q1:2020-21. Against the backdrop of a regulatory ban on banks that prevent them from distribution of dividends, many PVBs earmarked the entire required provision – or even more – in the March 2020 quarter itself. As a result, the provision coverage ratio (PCR) of SCBs improved to 66.2 per cent in end-March 2020 and further rose to 72.4 per cent by end-September 2020 (Chart IV.14a). This also impacted profitability of banks in varying degrees (Chart IV.14b).3

| Table IV.5: Cost of Funds and Return on Funds by Bank Groups | | (Per cent) | | Bank Group / Year | Cost of Deposits | Cost of Borrowings | Cost of Funds | Return on Advances | Return on Investments | Return on Funds | Spread | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 = 8-5 | | PSBs | 2018-19 | 5.01 | 4.81 | 4.99 | 8.07 | 7.20 | 7.79 | 2.80 | | | 2019-20 | 4.96 | 4.56 | 4.92 | 8.16 | 6.92 | 7.76 | 2.84 | | PVBs | 2018-19 | 5.14 | 6.64 | 5.40 | 9.78 | 6.99 | 9.01 | 3.61 | | | 2019-20 | 5.26 | 6.17 | 5.41 | 10.10 | 6.59 | 9.17 | 3.76 | | FBs | 2018-19 | 3.79 | 2.93 | 3.61 | 8.15 | 6.23 | 7.23 | 3.61 | | | 2019-20 | 3.65 | 4.07 | 3.73 | 8.45 | 6.71 | 7.59 | 3.86 | | SFBs | 2018-19 | 7.03 | 9.79 | 8.02 | 17.77 | 7.55 | 15.63 | 7.61 | | | 2019-20 | 8.20 | 9.84 | 8.66 | 19.87 | 7.54 | 17.32 | 8.66 | | PBs | 2018-19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | | | 2019-20 | 1.58 | - | 1.59 | - | 3.49 | 3.49 | 1.90 | | All SCBs | 2018-19 | 5.00 | 5.54 | 5.06 | 8.69 | 7.06 | 8.18 | 3.12 | | | 2019-20 | 5.00 | 5.36 | 5.04 | 8.94 | 6.81 | 8.28 | 3.23 | Notes: 1. Cost of deposits = Interest paid on deposits/Average of current and previous year’s deposits.

2. Cost of borrowings = (Interest expended - Interest on deposits)/Average of current and previous year’s borrowings.

3. Cost of funds = Interest expended / (Average of current and previous year’s deposits plus borrowings)

4. Return on advances = Interest earned on advances /Average of current and previous year’s advances.

5. Return on investments = Interest earned on investments /Average of current and previous year’s investments.

6. Return on funds = (Interest earned on advances + Interest earned on investments) / (Average of current and previous year’s advances plus investments).

7. Data include SFBs and PBs.

Source: Calculated from balance sheets of respective banks. | IV.26 At the system level, SCBs’ return on assets (RoA) and return on equity (RoE) turned positive during 2019-20, although PSBs and PBs remained a drag on banking system profitability (Table IV.6).

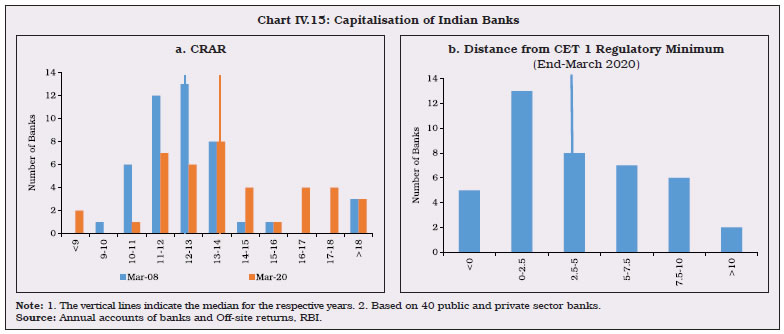

| Table IV.6: Return on Assets and Return on Equity of SCBs – Bank Group-wise | | (Per cent) | | Bank Group | PSBs | PVBs | FBs | SFBs | PBs | All SCBs | | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | | Return on Assets | -0.65 | -0.23 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 1.57 | 1.55 | 1.59 | 1.70 | - | -25.39 | -0.09 | 0.15 | | Return on Equity | -11.44 | -4.16 | 5.45 | 3.30 | 8.77 | 8.76 | 12.59 | 15.00 | - | -58.19 | -1.85 | 0.78 | | Source: Annual accounts of banks. | 4. Soundness Indicators IV.27 During 2019-20, SCBs strengthened their capital buffers, improved their asset quality and raised liquidity coverage ratios (LCR), although the leverage ratios marginally declined. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, these improvements in soundness indictors continued till September 2020 due to moratorium on loans till August 2020 and continuing asset classification standstill. However, an increase in the restructured advances ratio to 0.43 per cent at end-September 2020 from 0.36 in March 2020 may be indicative of incipient stress. 4.1 Capital Adequacy IV.28 The consistent improvement in the capital to risk-weighted assets ratio (CRAR) of SCBs since March 2015 continued throughout 2019-20 and 2020-21 so far, reaching 15.8 per cent by end-September 2020 (Table IV.7). | Table IV.7: Component-wise Capital Adequacy of SCBs | | (As at end-March) | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | | PSBs | PVBs | FBs | SCBs | | | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | | 1. Capital Funds | 6,38,553 | 6,99,872 | 6,01,046 | 6,54,772 | 1,69,598 | 1,88,660 | 14,09,197 | 15,43,304 | | i) Tier I Capital | 5,18,963 | 5,65,830 | 5,27,007 | 5,80,718 | 1,59,184 | 1,72,883 | 12,05,154 | 13,19,431 | | ii) Tier II Capital | 1,19,590 | 1,34,042 | 74,039 | 74,054 | 10,413 | 15,777 | 2,04,043 | 2,23,873 | | 2. Risk Weighted Assets | 52,32,524 | 54,46,253 | 37,39,838 | 39,56,956 | 8,74,432 | 10,65,869 | 98,46,793 | 1,04,69,078 | | 3. CRAR (1 as % of 2) | 12.2 | 12.9 | 16.1 | 16.5 | 19.4 | 17.7 | 14.3 | 14.7 | | Of which: Tier I | 9.9 | 10.4 | 14.1 | 14.7 | 18.2 | 16.2 | 12.2 | 12.6 | | Tier II | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.1 | | Source: Off-site returns, RBI. | Although at the system level, the capital position exceeded the regulatory minimum [10.875 per cent inclusive of capital conservation buffer (CCB)], a few banks breached the regulatory minimum. Mergers helped improve the capital position of constituent banks due to pooling of resources for various operations and other scale economies (Box IV.2). Deferred implementation of the last tranche of CCB as a regulatory response to potential impact of COVID-19 on capital position of banks also helped. The decline in GNPAs and fresh slippages, improved profitability and restriction on dividend pay-out by banks contributed to strengthening of capital position of banks. IV.29 There has been a visible shift in the CRAR distribution of banks between 2008 (onset of the global financial crisis) and 2020 (onset of COVID-19 pandemic). The median CRAR has increased from 12.3 in March 2008 to 13.3 in March 2020 (Chart IV.15a). Although Indian banks had comparatively stronger capital buffers while entering the global financial crisis (GFC), they have significantly weaker capital position in comparison to their global counterparts in the COVID-19 pandemic4. In terms of distance from regulatory minimum CET-I ratio (5.5 per cent plus capital conservation buffer of 1.875 per cent i.e., 7.375 per cent) banks are concentrated at the lower end the distribution (Chart IV.15b). Box IV.2: Effects of Merger on Indian Banking System Ten public sector banks were merged into four banks with effect from April 1, 2020 with the objective of creating next generation banks with strong national and global presence. Notwithstanding some initial hiccups, factors like government ownership, similar pay structure and career progression avenues for staff, and common core banking solutions helped smoothen the operationalisation of the merger (Table 1). The equity swap ratio between merged entities was another issue that was widely discussed but was settled ahead of the merger (Table 2). The merged entities can now reap benefits of synergy, especially in the case of branch network presence across regions. For example, United Bank of India, which had a large presence in the eastern region, will now benefit from the more diversified branch network of Punjab National Bank which had vast network in northern and central region before the merger. Similarly, Indian Bank – with concentrated presence in the southern part of the country – can now expand its reach in central and eastern parts due to its alliance with Allahabad Bank (Chart 1). | Table 1: Core Banking Solutions | | Banks | Merged Into | Core Banking Solution | Punjab National Bank (PNB)

Oriental bank of Commerce (OBC)

United Bank of India | Punjab National Bank | Finacle | Syndicate Bank

Canara Bank | Canara Bank | iFLex Cube (OFSS) | Andhra Bank

Union Bank of India

Corporation Bank | Union Bank of India | Finacle | Allahabad Bank

Indian Bank | Indian Bank | BaNCS |

| Table 2: Share Swap Ratios | | Punjab National Bank | • 1,150 equity shares of ₹2 each of Punjab National Bank for every 1,000 shares of ₹10 each of Oriental Bank of Commerce

• 121 equity shares of ₹2 each of Punjab National Bank for every 1,000 equity shares of ₹10 each of United Bank of India | | Canara Bank | • 158 equity shares of ₹10 each of Canara Bank for every 1,000 equity shares of ₹10 each of Syndicate Bank | | Union Bank of India | • 325 equity shares of ₹10 each of Union Bank of India for every 1,000 equity shares of ₹10 each of Andhra Bank

• 330 equity shares of ₹10 each of Union Bank of India for every 1,000 equity shares of ₹2 each of Corporation Bank | | Indian Bank | • 115 equity shares of ₹10 each of Indian Bank for every 1,000 equity shares of ₹10 each of Allahabad Bank | Merger helped strengthen the capital buffers of banks that were facing challenges in meeting regulatory requirements (Table 3). | Table 3: CRAR of Banks: Pre- and Post-Merger | | (Per cent) | | | March 31, 2020

(Pre-Merger) | June 30, 2020

(Post-Merger) | | Punjab National Bank | 14.14 | 12.63 | | Oriental Bank of Commerce | 11.55 | | United Bank | 5.56 | | Canara Bank | 13.65 | 12.77 | | Syndicate Bank | 11.52 | | Union Bank of India | 12.81 | 11.62 | | Andhra Bank | 11.12 | | Corporation Bank | 11.53 | | Indian Bank | 14.12 | 13.45 | | Allahabad Bank | 12.01 |

| Table 4: NNPA Ratio | | (Per cent) | | | March 31, 2020

(Pre-Merger) | June 30, 2020

(Post-Merger) | | Punjab National Bank | 5.80 | 5.39 | | Oriental Bank of Commerce | 5.00 | | United Bank | 4.88 | | Canara Bank | 4.18 | 4.08 | | Syndicate Bank | 4.61 | | Union Bank of India | 5.49 | 4.75 | | Andhra Bank | 4.92 | | Corporation Bank | 5.14 | | Indian Bank | 3.13 | 3.76 | | Allahabad Bank | 5.66 |

Table 5: Provision Coverage Ratio

(Without write-off adjusted, in per cent) | | | March 31, 2020

(Pre-Merger) | June 30, 2020

(Post-Merger) | | Punjab National Bank | 62.39 | 64.47 | | Oriental Bank of Commerce | 62.84 | | United Bank | 66.86 | | Canara Bank | 50.20 | 56.27 | | Syndicate Bank | 63.44 | | Union Bank of India | 64.37 | 69.61 | | Andhra Bank | 72.80 | | Corporation Bank | 66.26 | | Indian Bank | 53.11 | 66.92 | | Allahabad Bank | 70.18 | Although it is difficult to isolate the impact of mergers from other forces acting concomitantly, the improvement in provisions helped in containing the net NPA ratios (Table 4 and 5). The consolidation may have also helped improve the operating profit per employee across banks. | IV.30 With capital infusion by the Government, PSBs improved their CRARs despite the increase in risk weighted assets (RWAs). With the budgeted capital infusion of ₹70,000 crores in 2019-20, the Government has infused ₹3.16 lakh crore in the last five years in these banks. SCBs shored up their capital position to strengthen loss-absorption capacity against imminent COVID-19 induced loan delinquencies. Apart from internal capital generation and recapitalisation (in case of PSBs) by the Government, banks raised capital from the market through public issues, preferential allotment, qualified institutional placement (QIP) and by selling non-core assets. PSBs abstained from public issues due to depressed valuations (Table IV.8).

| Table IV.8: Public and Rights Issues by the Banking Sector | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Year | PSBs | PVBs | Total | Grand Total | | Equity | Debt | Equity | Debt | Equity | Debt | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8= (6+7) | | 2018-19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | | 2019-20 | - | - | 410 | - | 410 | - | 410 | | 2020-21* | - | - | 15,000 | - | 15,000 | - | 15,000 | Note: 1. *: Up to November 2020.

2. -: Nil/Negligible.

Source: SEBI. |

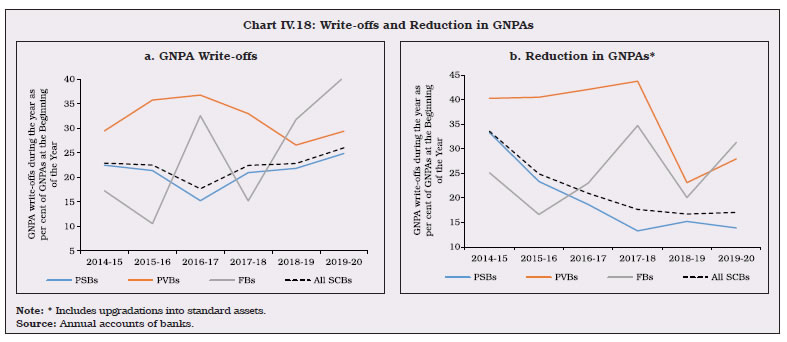

| Table IV.9: Resources Raised by Banks through Private Placements | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 (up to November) | | No. of Issues | Amount Raised | No. of Issues | Amount Raised | No. of Issues | Amount Raised | | PSBs | 13 | 15,190 | 20 | 29,573 | 15 | 36,439 | | PVBs | 13 | 19,943 | 8 | 23,121 | 3 | 32,443 | | Source: BSE, NSE and Merchant Bankers. | IV.31 Going forward, almost all major banks have announced plans to raise capital in 2020-21 either through debt or through equity or a combination of the two. A few major PVBs have taken a lead in raising capital but smaller lenders, especially the ones with already weak balance sheets, are conspicuous by their absence, partly reflecting uncertainty as to whether or not they will be able to raise resources in prevailing market conditions. IV.32 During 2019-20, the amount raised by PSBs through QIP and bond issuances on a private placement basis was almost double that of a year ago. Both PSBs and PVBs raised higher capital through private placements during 2020-21 so far (up to November) than a year ago (Table IV.9). Many of these bonds come under the category of Basel III compliant tier II bonds, which help shore up banks’ capital positions. 4.2 Leverage and Liquidity IV.33 The Leverage ratio, defined as the ratio of Tier I capital to total exposure, serves as a supplement to risk-based capital ratios to constrain the build-up of leverage. By end-March 2020, the leverage ratio declined marginally to 6.5 per cent from 6.6 per cent a year ago, driven by foreign banks (FBs) whose derivative exposure rose sharply. However, leverage ratio of SCBs again rose to 7.0 per cent by September 2020. Despite the reduction in regulatory requirements, effective October 2019, the leverage ratio of PSBs and PVBs witnessed a marginal uptick on improvement in capital positions while their total exposure remained stable (Chart IV.16a). IV.34 Of the two standards for funding liquidity prescribed by the Basel Committee, LCR has been effective in India since January 1, 2015 (the implementation of the net stable funding ratio (NSFR) has been deferred to April 1, 2021). As at end-March 2020, LCRs of SCBs rose to 159.1 per cent from 128.9 per cent in the previous year, given the low credit off-take and risk aversion among banks (Chart IV.16b). Despite the regulatory relaxation given to banks to maintain LCR at a lower rate of 80 per cent since April 17, 2020, the system-wide LCR was maintained at 171 per cent as at end September 2020. 4.3 Non-performing Assets IV.35 The moderation in the GNPA ratio, which started after the peak in March 2018, continued through 2019-20 and 2020-21 so far, to reach 7.5 per cent by end-September 2020. The improvement was driven by lower slippages which declined to 0.74 per cent in September 2020 and resolution of a few large accounts through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). Fresh slippages remained the highest among PSBs (Chart IV.17a &b). IV.36 The modest GNPA ratio of 7.5 per cent at end-September 2020 veils the strong undercurrent of slippage. The accretion to NPAs as per the Reserve Bank’s Income Recognition and Asset Classification (IRAC) norms would have been higher in the absence of the asset quality standstill provided as a COVID-19 relief measure (Table IV.10). Given the uncertainty induced by COVID-19 and its real economic impact, the asset quality of the banking system may deteriorate sharply, going forward. IV.37 The rapid credit growth during 2005-12, coupled with absence of strong credit appraisal and monitoring standards and wilful defaults, are responsible for sizeable asset impairments in subsequent years.

| Table IV.10: Asset Classification as per IRAC Norms | | (As at end-September 2020) | | | As Reported (Per Cent) | As per IRAC Norms (Per cent) | Difference (Percentage points) | | GNPA Ratio | NNPA Ratio | GNPA Ratio | NNPA Ratio | GNPA Ratio | NNPA Ratio | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | (4-2) | (5-3) | | Bank of Baroda | 9.14 | 2.51 | 9.33 | 2.67 | 0.19 | 0.16 | | State Bank of India | 5.28 | 1.59 | 5.88 | 2.08 | 0.60 | 0.49 | | Union Bank of India | 14.71 | 4.13 | 15.37 | 4.76 | 0.66 | 0.63 | | Axis Bank | 3.94 | 0.98 | 4.28 | 1.03 | 0.10 | 0.05 | | Bandhan Bank | 1.18 | 0.36 | 1.54 | 0.72 | 0.36 | 0.36 | | HDFC Bank | 1.08 | 0.17 | 1.37 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.18 | | ICICI Bank | 5.63 | 1.00 | 5.36 | 1.12 | 0.19 | 0.12 | | IDFC First Bank | 1.62 | 0.43 | 1.87 | 0.60 | 0.25 | 0.17 | | Kotak Mahindra Bank | 2.55 | 0.64 | 2.70 | 0.74 | 0.15 | 0.10 | | Source: OSMOS Supervisory Returns. | IV.38 The quantum of GNPAs of SCBs declined for the second consecutive year. With substantial increase in provisioning, the net NPA ratio of SCBs moderated to 2.8 per cent by end-March 2020 (Table IV.11). According to Supervisory Returns with the Reserve Bank, the net NPA ratio of SCBs further declined to 2.2 per cent by end-September 2020. IV.39 The reduction in NPAs during the year was largely driven by write-offs (Chart IV.18a and b). NPAs older than four years require 100 per cent provisioning and, therefore, banks may prefer to write them off. In addition, banks voluntarily write-off NPAs in order to clean up their balance-sheets, avail tax benefits and optimise the use of capital. At the same time, borrowers of written-off loans remain liable for repayment. IV.40 With these developments, the share of standard assets in total advances increased in SCBs except for PVBs and SFBs during 2019-20. Concomitantly, the share of doubtful assets declined while that of loss assets rose (Table IV.12). | Table IV.11: Movements in Non-Performing Assets by Bank Group | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Item | PSBs* | PVBs | FBs | SFBs | All SCBs# | | Gross NPAs | | | | | | | Closing Balance for 2018-19 | 7,39,541 | 1,83,604 | 12,242 | 1,087 | 9,36,474 | | Opening Balance for 2019-20 | 7,17,850 | 1,83,604 | 12,242 | 1,660 | 9,15,355 | | Addition during the year 2019-20 | 2,38,464 | 1,31,249 | 6,751 | 1,764 | 3,78,228 | | Reduction during the year 2019-20 | 99,692 | 51,335 | 3,832 | 1,046 | 1,55,905 | | Written-off during the year 2019-20 | 1,78,305 | 53,949 | 4,953 | 669 | 2,37,876 | | Closing Balance for 2019-20 | 6,78,317 | 2,09,568 | 10,208 | 1,709 | 8,99,803 | | Gross NPAs as per cent of Gross Advances** | | | | | | | 2018-19 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 9.1 | | 2019-20 | 10.3 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 8.2 | | Net NPAs | | | | | | | Closing Balance for 2018-19 | 2,85,122 | 67,309 | 2,051 | 586 | 3,55,068 | | Closing Balance for 2019-20 | 2,30,918 | 55,746 | 2,084 | 784 | 2,89,531 | | Net NPAs as per cent of Net Advances** | | | | | | | 2018-19 | 4.8 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3.7 | | 2019-20 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.8 | Notes: 1. #: Data includes scheduled SFBs.

2. *: Closing balance for 2018-19 and opening balance for 2019-20 do not match due to amalgamation of Dena Bank and Vijaya Bank into Bank of Baroda.

3. **: Calculated by taking gross NPAs from annual accounts of respective banks and gross advances from off-site returns (global operations).

Source: Annual accounts of banks and off-site returns (global operations), RBI. |

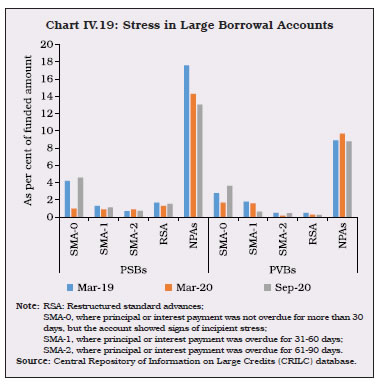

IV.41 Large borrowal accounts (exposure of ₹5 crore and above) constituted 79.8 per cent of NPAs and 53.7 per cent of total loans at end-September 2020. During 2019-20, PSBs’ GNPA ratio as well as the ratio of restructured standard assets to total funded amounts emanating from larger borrowal accounts trended downwards. On the contrary, PVBs experienced an increasing share of NPAs in respect of such accounts. The share of special mention accounts (SMA-0) witnessed a sharp rise in September 2020. This may be an initial sign of stress after lifting of moratorium on August 31, 2020. However, the share of other categories of SMAs i.e., SMA-1 and SMA-2 remained at a relatively lower level (Chart IV.19). 4.4 Recoveries IV.42 Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), under which recovery is incidental to rescue of companies, remained the dominant mode of recovery. However, the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest Act, 2002 (SARFAESI) channel also emerged as a major mode of recovery in terms of the amount recovered as well as the recovery rate (Table IV.13). With the applicability of the SARFAESI Act extended to co-operative banks, recovery through this channel is expected to gain further traction. Going forward, insolvency outcomes will hinge around uncertainties relating to COVID-19. The government has suspended any fresh initiation of insolvency proceedings in respect of defaults arising during one year commencing March 25, 2020 to shield companies impacted by COVID-19. | Table IV.12: Classification of Loan Assets by Bank Group | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Bank Group | End-March | Standard Assets | Sub-Standard Assets | Doubtful Assets | Loss Assets | | Amount | Per cent* | Amount | Per cent* | Amount | Per cent* | Amount | Per cent* | | PSBs | 2019 | 50,86,874 | 87.8 | 1,37,377 | 2.4 | 5,06,492 | 8.7 | 66,239 | 1.1 | | | 2020 | 53,27,903 | 89.2 | 1,32,530 | 2.2 | 4,04,724 | 6.8 | 1,07,163 | 1.8 | | PVBs | 2019 | 31,03,581 | 95.2 | 42,440 | 1.3 | 1,04,696 | 3.2 | 9,576 | 0.3 | | | 2020 | 34,14,554 | 94.9 | 56,588 | 1.6 | 92,396 | 2.6 | 34,986 | 1.0 | | FBs | 2019 | 3,94,638 | 97.0 | 3,190 | 0.8 | 8,019 | 2.0 | 1,034 | 0.3 | | | 2020 | 4,25,857 | 97.7 | 3,273 | 0.8 | 5,775 | 1.3 | 1,161 | 0.3 | | SFBs** | 2019 | 61,652 | 98.2 | 719 | 1.1 | 360 | 0.6 | 44 | 0.1 | | | 2020 | 89,800 | 98.1 | 1,023 | 1.1 | 648 | 0.7 | 39 | 0.0 | | All SCBs | 2019 | 86,46,745 | 90.8 | 1,83,726 | 1.9 | 6,19,567 | 6.5 | 76,894 | 0.8 | | | 2020 | 92,58,114 | 91.7 | 1,93,413 | 1.9 | 5,03,543 | 5.0 | 1,43,349 | 1.4 | Notes: 1. Constituent items may not add up to the total due to rounding off.

2. *: As per cent to gross advances.

3. **: Refers to scheduled SFBs.

Source: Off-site returns (domestic operations), RBI. |

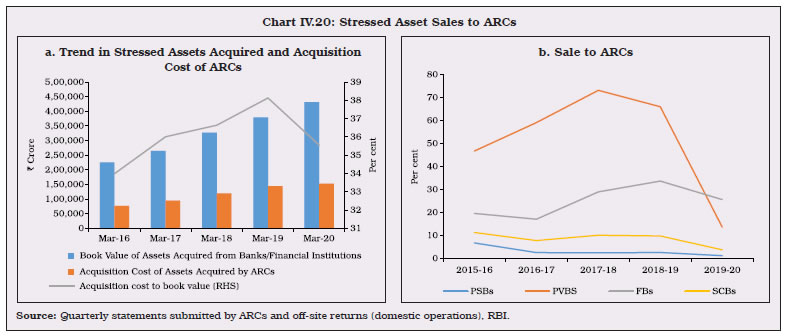

IV.43 Apart from recovery through various resolution mechanisms, banks also clean up balance sheets through sale of NPAs to assets reconstruction companies (ARCs) for a quick exit. During 2019-20, asset sales by SCBs to ARCs declined which could probably be due to SCBs opting for other resolution channels such as IBC and SARFAESI. The acquisition cost of ARCs as a proportion to the book value of assets declined suggesting lower realisable value of the assets (Chart IV.20). | Table IV.13: NPAs of SCBs Recovered through Various Channels | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Recovery Channel | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | | No. of cases referred | Amount involved | Amount recovered* | Col. (4) as per cent of Col. (3) | No. of cases referred | Amount involved | Amount recovered* | Col. (8) as per cent of Col. (7) | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | | Lok Adalats | 40,87,555 | 53,484 | 2,750 | 5.1 | 59,86,790 | 67,801 | 4,211 | 6.2 | | DRTs | 51,679 | 2,68,413 | 10,552 | 3.9 | 40,818 | 2,45,570 | 10,018 | 4.1 | | SARFAESI Act | 2,35,437 | 2,58,642 | 38,905 | 15.0 | 1,05,523 | 1,96,582 | 52,563 | 26.7 | | IBC | 1,152@ | 1,45,457 | 66,440 | 45.7 | 1,953@ | 2,32,478 | 1,05,773 | 45.5 | | Total | 43,75,823 | 7,25,996 | 1,18,647 | 16.3 | 61,35,084 | 7,42,431 | 1,72,565 | 23.2 | Notes: 1. Data are provisional.

2. DRTs: Debt Recovery Tribunals

3. *: Refers to the amount recovered during the given year, which could be with reference to the cases referred during the given year as well as during the earlier years. In the case of IBC, the realisation does not include amount realisable for operational creditors, from guarantors of corporate debtors and disposal of avoidance transactions.

4. @: Cases admitted by National Company Law Tribunals (NCLTs) under IBC. However, figures appearing for amount involved and amount recovered are for cases whose resolution plan was approved during the given financial year i.e. 81 cases for 2018-19 and 135 cases in 2019-20. Also, the amount recovered refers to realisables by all financial creditors, not just SCBs.

5. The resolution plan of Essar Steel India Ltd. was approved in 2018-19. However, as apportionment among creditors was settled in 2019-20, the recovery is reflected in the latter year data.

Source: Off-site returns, RBI and Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI). |

IV.44 The share of security receipts (SRs) subscribed to by banks steadily declined, reaching 66.7 per cent by end-March 2020 from 80.5 per cent at end-March 2018 as ARCs were incentivised to increase skin-in-the-game and diversify the investor base by bringing in other financial institutions (Table IV.14). 4.5 Frauds in the Banking Sector IV.45 Operational risk has emerged as a major source of risk. Although 98 per cent of frauds in terms of value were related to loans, their occurrence was spread over several previous years (Table IV.15, Appendix Table IV.15). There was a concentration of large value frauds, with the top fifty credit-related frauds constituting 76 per cent of the total amount reported as frauds during 2019-20. IV.46 Further, the banking relationship and date of sanction of credit facility in many of these accounts were much older. For instance, the majority of frauds reported till September 2020 both in terms of number and amount had occurred in years prior to 2017-18 (Table IV.16). | Table IV.14: Details of Financial Assets Securitised by ARCs | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Item | March-2018 | March-2019 | March-2020 | | 1. Book Value of Assets Acquired | 3,27,400 | 3,79,383 | 4,31,339 | | 2. Security Receipt issued by ARCs | 1,18,351 | 1,42,885 | 1,51,435 | | 3. Security Receipts Subscribed to by | | | | | (a) Banks | 95,299 | 99,840 | 1,00,934 | | (b) ARCs | 18,924 | 26,470 | 29,435 | | (c) FIIs | 505 | 1,681 | 10,366 | | (d) Others (Qualified Institutional Buyers) | 3,622 | 14,895 | 10,700 | | 4. Amount of Security Receipts Completely Redeemed | 8,413 | 12,240 | 17,947 | | 5. Security Receipts Outstanding | 98,203 | 1,12,651 | 1,07,877 | | Source: Quarterly statements submitted by ARCs. |

| Table IV.15: Frauds in Various Banking Operations Based on the Date of Reporting | | (Cases in number and amount in ₹ crore) | | Area of Operation | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2019-20

(April-September) | 2020-21

(April-September) | | Number of frauds | Amount involved | Number of frauds | Amount involved | Number of frauds | Amount involved | Number of frauds | Amount involved | Number of frauds | Amount involved | | Advances | 2,525 | 22,558 | 3,604 | 64,548 | 4,611 | 1,82,117 | 2,441 | 1,10,639 | 1,664 | 63,950 | | Off-balance Sheet | 20 | 16,288 | 33 | 5,538 | 34 | 2,445 | 22 | 2,059 | 14 | 439 | | Forex Transactions | 9 | 1,426 | 13 | 695 | 8 | 54 | 3 | 52 | 1 | 0 | | Card/Internet | 2,059 | 110 | 1,866 | 71 | 2,677 | 129 | 1,234 | 53 | 1244 | 49 | | Deposits | 691 | 457 | 593 | 148 | 530 | 616 | 274 | 484 | 245 | 148 | | Inter-Branch Accounts | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | | Cash | 218 | 40 | 274 | 56 | 371 | 63 | 208 | 24 | 132 | 21 | | Cheques/DDs, etc. | 207 | 34 | 189 | 34 | 202 | 39 | 98 | 13 | 76 | 48 | | Clearing Accounts, etc. | 37 | 6 | 24 | 209 | 22 | 7 | 15 | 6 | 4 | 1 | | Others | 144 | 247 | 200 | 244 | 250 | 174 | 113 | 44 | 106 | 25 | | Total | 5,916 | 41,167 | 6,799 | 71,543 | 8,707 | 1,85,644 | 4,410 | 1,13,374 | 3,488 | 64,681 | Notes: 1. Refers to frauds of ₹1 lakh and above.

2. The figures reported by banks and financial institutions are subject to change based on revisions filed by them.

3. Frauds reported in a year could have occurred several years prior to year of reporting.

4. Amounts involved are as reported and do not reflect the amount of loss incurred. Depending on recoveries, the loss incurred gets reduced. Further, the entire amount involved in loan accounts is not necessarily diverted.

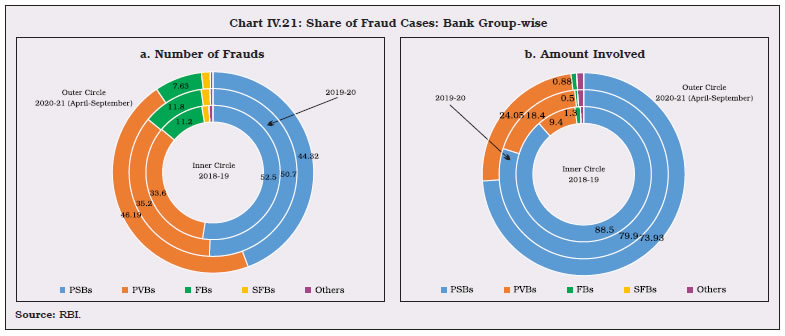

Source: RBI. | IV.47 Although around 80 per cent of the frauds involving amount of ‘more than ₹ one lakh’ were reported by PSBs, their share in total reporting – both number of cases as well as amounts involved – declined in 2019-20 (Chart IV.21). | Table IV.16: Frauds in Various Banking Operations Based on Date of Occurrence | | (Cases in number and amount in ₹ crore) | | Area of operation | Prior to 2017-18 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21

(April-September) | | No. | Amount | No. | Amount | No. | Amount | No. | Amount | No. | Amount | | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | | Advances | 7,612 | 2,58,258 | 1,944 | 22,793 | 1,705 | 29,565 | 1,023 | 21,455 | 120 | 1,103 | | Off-balance sheet | 70 | 20,640 | 11 | 1,143 | 18 | 2924 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | | Foreign Exchange Transactions | 15 | 1,940 | 5 | 83 | 5 | 145 | 6 | 7 | - | - | | Card/Internet | 348 | 28 | 2,168 | 105 | 2,050 | 80 | 2,463 | 119 | 817 | 26 | | Deposits | 527 | 666 | 583 | 345 | 521 | 137 | 361 | 191 | 67 | 30 | | Inter-branch accounts | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | - | - | 1 | 0 | | Cash | 99 | 41 | 214 | 39 | 270 | 53 | 342 | 31 | 70 | 16 | | Cheques/ demand drafts | 103 | 24 | 210 | 41 | 158 | 26 | 174 | 62 | 29 | 2 | | Clearing, etc accounts | 17 | 6 | 36 | 9 | 22 | 206 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | | Others | 228 | 347 | 162 | 167 | 172 | 51 | 113 | 123 | 25 | 4 | | Total | 9,025 | 2,81,951 | 5,336 | 24,725 | 4,924 | 33,187 | 4,493 | 21,990 | 1,132 | 1,182 | Notes: 1. Refers to frauds of ₹1 lakh and above

2. The figures reported by banks & select FIs are subject to change based on revisions filed by them.

3. Data based on ‘date of occurrence’ may change for a period of time as frauds reported late but having occurred earlier would get added. For example, for frauds occurring in 2016-17, the data generated as on April 1, 2018 would be different from the one generated as on April 1, 2019 because the frauds reported between April 1, 2018 and March 31, 2019 but occurred in the year 2016-17 get added in latter report.

Source: RBI. |

5. Sectoral Bank Credit: Distribution and NPAs IV.48 The deceleration in credit growth during 2019-20 and 2020-21 so far (up to September) was spread across sectors but was pronounced in the case of industry and services partly reflecting elevated levels of sectoral NPAs (Table IV.17 and Chart IV.22a). Low credit demand, coupled with corporate deleveraging, also played a role. The pick-up in resolution and decline in slippages helped alleviate stress in large accounts. NPAs in the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) sector were contained by the facility to restructure their loans5 (Chart IV.22b). Slowdown in credit to NBFCs was partly offset by banks’ investment in their debt papers, incentivised by targeted long-term repo operations (TLTRO) scheme of the Reserve Bank. | Table IV.17: Sectoral Deployment of Gross Bank Credit | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Sr. No. | Item | Outstanding as on | Per cent variation (y-o-y) | | Mar-19 | Mar-20 | Sep-20 | 2018-19* | 2019-20** | 2020-21

(up to September)^ | | 1 | Agriculture & Allied Activities | 12,17,594 | 12,39,575 | 12,91,752 | 10 | 1.8 | 6.6 | | 2 | Industry, of which | 32,93,638 | 32,52,801 | 31,30,493 | 5.2 | -1.2 | -1.4 | | | 2.1 Micro & Small Industries | 4,39,811 | 4,37,658 | 4,63,564 | 5.2 | -0.5 | 6.6 | | | 2.2 Medium | 1,23,843 | 1,12,376 | 1,40,247 | -1.7 | -9.3 | 18.6 | | | 2.3 Large | 26,11,567 | 26,11,369 | 24,42,320 | 6.1 | -0.01 | -3.5 | | 3 | Services, of which | 26,02,287 | 27,54,824 | 26,89,484 | 25.1 | 5.9 | 4.3 | | | 3.1 Trade | 5,83,930 | 6,28,171 | 6,51,990 | 12.4 | 7.6 | 11.5 | | | 3.2 Commercial Real Estate | 2,43,122 | 2,66,357 | 2,54,960 | 18.9 | 9.6 | -1.1 | | | 3.3 Tourism, Hotels & Restaurants | 56,194 | 60,039 | 62,313 | 7.9 | 6.8 | 9.6 | | | 3.4 Computer Software | 22,236 | 24,404 | 22,566 | -0.3 | 9.8 | 0.0 | | | 3.5 Non-Banking Financial Companies | 6,27,089 | 7,36,447 | 7,17,778 | 38.4 | 17.4 | 1.1 | | 4 | Retail Loans, of which | 23,04,313 | 26,59,250 | 27,27,946 | 18.6 | 15.4 | 10.4 | | | 4.1 Housing Loans | 12,04,362 | 13,96,445 | 14,37,886 | 19.5 | 15.9 | 10.3 | | | 4.2 Consumer Durables | 9,195 | 11,154 | 16,786 | -51.7 | 21.3 | 88.6 | | | 4.3 Credit Card Receivables | 1,11,361 | 1,32,076 | 1,40,824 | 34.5 | 18.6 | 15.7 | | | 4.4 Auto Loans | 2,69,677 | 2,89,366 | 2,98,672 | 12.9 | 7.3 | 8.4 | | | 4.5 Education Loans | 76,233 | 79,056 | 80,092 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 2.7 | | | 4.6 Advances against Fixed Deposits (incl. FCNR (B), etc.) | 77,135 | 80,753 | 71,482 | -0.1 | 4.7 | 13.0 | | | 4.7 Advances to Individuals against Shares, Bonds, etc. | 9,339 | 5,619 | 6,977 | 46.3 | -39.8 | -19.4 | | | 4.8 Other Retail Loans | 5,47,010 | 6,64,781 | 6,75,229 | 25.6 | 21.5 | 10.4 | | 5 | Gross Bank Credit | 95,26,932 | 1,00,98,420 | 1,00,63,699 | 13.4 | 6 | 5.1 | Note: 1. Figures in the table may not tally with the figures released by RBI in ‘Sectoral Deployment of Bank Credit’ every month due to difference in coverage of banks.

2. *: March 2019 over March 2018.

3. **: March 2020 over March 2019.

4. ^: September 2020 over September 2019.

Source: Off-site returns (domestic operations), RBI. |

IV.49 Construction and power sectors were saddled with problems related to land acquisition, delay in getting various clearances, long gestation periods, contractual issues and cost overruns, and consequently had high NPA levels. In the gems and jewellery sector, NPAs increased with the exports declining during 2019-20 (Chart IV.23). IV.50 PVBs have been the engine of credit growth during the last few years. In a reversal during 2019-20, however, their loan growth decelerated across sectors. Lending to industry and agriculture sector by PVBs and PSBs also slowed down or declined (Chart IV.24a). The aggressive credit growth of PVBs to services and retail segments in the last few years – which surpassed 30 per cent mark in 2018-19 – came down sharply, even as PSBs managed to hold on to market shares in the retail segment (Chart IV.24b).

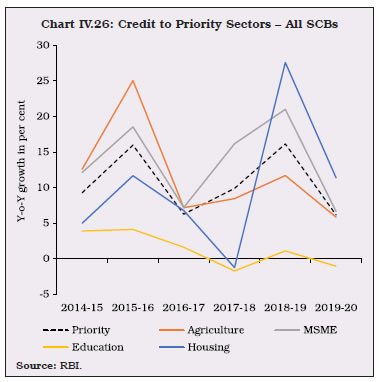

5.1 Unsecured Loans IV.51 The share of unsecured lending in the portfolio of both banks and non-banks has increased sharply over the last three years (Chart IV.25a). In recent years, SCBs have been reorienting their loan book away from the industrial sector and towards retail loans in view of lower delinquency rates of the latter. The growing share of unsecured credit card loans of SCBs – up from 3.1 per cent to 5.2 per cent within a span of five years – does not, however, augur well for their risk profile (Chart IV.25b). 5.2 Priority Sector Credit IV.52 Priority sector credit decelerated across constituent categories as well as across bank groups during 2019-20 (Chart IV.26). The deceleration in agricultural credit was led by Kisan Credit Card loans (Appendix Table IV.3). In the case of priority sector education loans (amount less than ₹10 lakh), the retrenchment, reflecting their high NPAs, is in sharp contrast with non-priority sector education loans, which have continued to grow.  IV.53 During 2019-20, although all the bank-groups managed to achieve the overall priority sector lending (PSL), several sub-targets like those for agriculture, micro enterprises, small and marginal farmers (SMF) and non-corporate individual farmers were not achieved by some of them (Table IV.18). The revised priority sector lending guidelines issued in September 2020 are expected to increase lending to small and marginal farmers (SMFs) and weaker sections as targets prescribed for these categories are being raised in a phased manner. The guidelines are also expected to boost credit to start-ups, renewable energy, and health infrastructure in line with emerging national priorities. | Table IV.18: Priority Sector Lending by Banks | | (As on March 31, 2020) | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Item | Target/ sub-target

(per cent of ANBC/ CEOBE) | Public Sector Banks | Private Sector Banks | Foreign Banks | Small Finance Banks | | Amount outstanding | Per cent of ANBC/ CEOBE | Amount outstanding | Per cent of ANBC/ CEOBE | Amount outstanding | Per cent of ANBC/ CEOBE | Amount outstanding | Per cent of ANBC/ CEOBE | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | | Total Priority Sector Advances | 40/75* | 23,14,242 | 41.05 | 12,72,745 | 40.32 | 1,67,095 | 40.80 | 45,566 | 88.22 | | of which | | | | | | | | | | | Total Agriculture | 18 | 9,71,334 | 17.23 | 5,03,939 | 15.96 | 41,745 | 18.25 | 13,917 | 26.94 | | Small and marginal farmers | 8 | 5,13,400 | 9.11 | 2,29,420 | 7.27 | 19,168 | 8.38 | 13,052 | 25.27 | | Non-corporate Individual Farmers# | 12.11 | 7,11,852 | 12.63 | 3,45,305 | 10.94 | 23,382 | 10.22 | 15,138 | 29.31 | | Micro Enterprises | 7.5 | 3,96,159 | 7.03 | 2,53,592 | 8.03 | 17,477 | 7.64 | 15,251 | 29.53 | | Weaker Sections | 10 | 6,83,876 | 12.13 | 3,40,182 | 10.78 | 24,148 | 10.56 | 30,260 | 58.59 | Notes: 1. Amount outstanding and achievement percentage are based on the average achievement of banks for four quarters of the financial year

2. *: Total priority sector lending target for Small Finance Banks is 75 per cent.

3. #: Target for non-corporate farmers is based on the system-wide average of the last three years’ achievement. For FY 2019-20, the applicable system wide average figure is 12.11 per cent.

4. For foreign banks having less than 20 branches, only the total PSL target of 40 per cent is applicable.

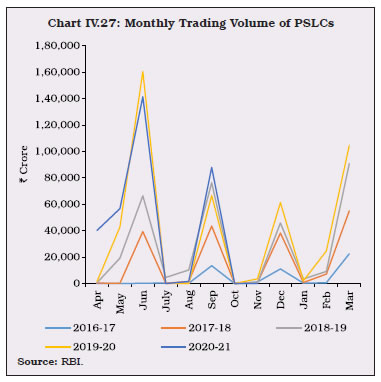

Source: RBI. | IV.54 The Reserve Bank had introduced Priority Sector Lending Certificates (PSLCs) in April 2016 as a market mechanism to incentivize banks to lend to the priority sector. Under this mechanism, over-achievers can issue PSLCs against the surplus in respect of a target/sub-target. Four types of certificates viz. PSLC General, PSLC-Agriculture (A), PSLC-Micro Enterprises (ME) and PSLC-Small and Marginal farmer (SMF) can be traded on the Reserve Bank’s e-Kuber platform. The total trading volume of PSLCs increased by 42.8 per cent to ₹4,67,789 crore during 2019-20 as against 74.6 per cent growth during 2018-19. In H1:2020-21, trading volume increased by 20.7 per cent from a year ago. Trading volumes tend to spike at the end of each quarter as buyers vie with each other to meet quarterly priority sector targets (Chart IV.27). Among the four PSLC categories, the highest trading was recorded in PSLC-General and PSLC-SMF.

| Table IV.19: Weighted Average Premium on Various Categories of PSLCs | | (Per cent) | | | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2019-20

(Apr-Sep) | 2020-21

(Apr-Sep) | | PSLC-A | 1.87 | 1.29 | 0.79 | 1.17 | 1.32 | 1.61 | | PSLC-ME | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.54 | | PSLC-SMF | 1.72 | 1.54 | 1.15 | 1.58 | 1.65 | 1.87 | | PSLC-G | 0.7 | 0.59 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.49 | | Source: RBI. | IV.55 During the year, priority sector areas where lending is comparatively more challenging were rewarded by higher premiums for PSLCs, e.g., the PSLC-SMF category commands almost four times higher premium than PSLC-ME and PSLC-General (Table IV.19). Commensurately, the growth in organic lending6 by banks to the SMF category was highest among all categories. IV.56 PSBs that carry a strong agriculture lending portfolio, have benefitted from the high premiums in PSLC-A and PSLC-SMF categories. After introduction of PSLCs, PVBs have increased their lending to micro enterprises exceeding their sub-target, although they are net buyers of PSLCs in agriculture and SMF sub-categories (Chart IV.28). FBs are net buyers and SFBs are net sellers across all the sub-categories of PSLCs. IV.57 PSBs and PVBs are the largest buyers as well as sellers of PSLCs on account of their larger loan books. On a net basis, PSBs which were net sellers till the previous year, turned buyers due to lending shortfalls in respect of overall priority sector and sub-target for lending to micro enterprises (Chart IV.29). IV.58 At end-March 2020, the GNPA ratio relating to priority sector loans increased to 8.3 per cent from 7.6 per cent in the previous year, driven primarily by delinquencies in agricultural and micro and small enterprises lending (Table IV.20).

| Table IV.20: Sector-wise GNPAs of Banks | | (As at end-March) | | (Amount in ₹ crore) | | Bank Group | Priority Sector | Of which | Non-priority Sector | Total NPAs | | Agriculture | Micro and Small Enterprises | Others | | Amt. | Per cent# | Amt. | Per cent# | Amt. | Per cent# | Amt. | Per cent# | Amt. | Per cent# | Amt. | Per cent# | | PSBs* | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2019 | 2,12,315 | 29.9 | 93,146 | 13.1 | 86,705 | 12.2 | 32,464 | 4.6 | 4,97,794 | 70.1 | 7,10,109 | 100 | | 2020 | 2,36,212 | 36.7 | 1,11,571 | 17.3 | 90,769 | 14.1 | 33,872 | 5.3 | 4,08,205 | 63.3 | 6,44,417 | 100 | | PVBs | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2019 | 29,721 | 19.0 | 12,679 | 8.1 | 12,796 | 8.17 | 4,246 | 2.7 | 1,26,991 | 81.0 | 1,56,712 | 100 | | 2020 | 36,219 | 19.7 | 14,462 | 7.9 | 16,111 | 8.76 | 5,646 | 3.1 | 1,47,751 | 80.3 | 1,83,970 | 100 | | FBs | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2019 | 1,103 | 9.0 | 105 | 0.9 | 616 | 5.0 | 382 | 3.1 | 11,139 | 91.0 | 12,243 | 100 | | 2020 | 1,692 | 16.6 | 376 | 3.7 | 1,070 | 10.5 | 246 | 2.4 | 8,498 | 83.4 | 10,189 | 100 | | SFBs | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2019 | 893 | 79.5 | 138 | 12.3 | 583 | 51.9 | 172 | 15.3 | 230 | 20.5 | 1123 | 100 | | 2020 | 1,376 | 80.5 | 256 | 15.0 | 754 | 44.1 | 367 | 21.4 | 333 | 19.5 | 1709 | 100 | | All SCBs | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2019 | 2,44,033 | 27.7 | 1,06,069 | 12.1 | 1,00,700 | 11.4 | 37,264 | 4.2 | 6,36,154 | 72.3 | 8,80,186 | 100 | | 2020 | 2,75,499 | 32.8 | 1,26,664 | 15.1 | 1,08,704 | 12.9 | 40,131 | 4.8 | 5,64,787 | 67.2 | 8,40,286 | 100 | Notes: 1. Amt.: – Amount; Per cent: Per cent of total NPAs.

2. Constituent items may not add up to the total due to rounding off.

3. # Share in total NPAs.

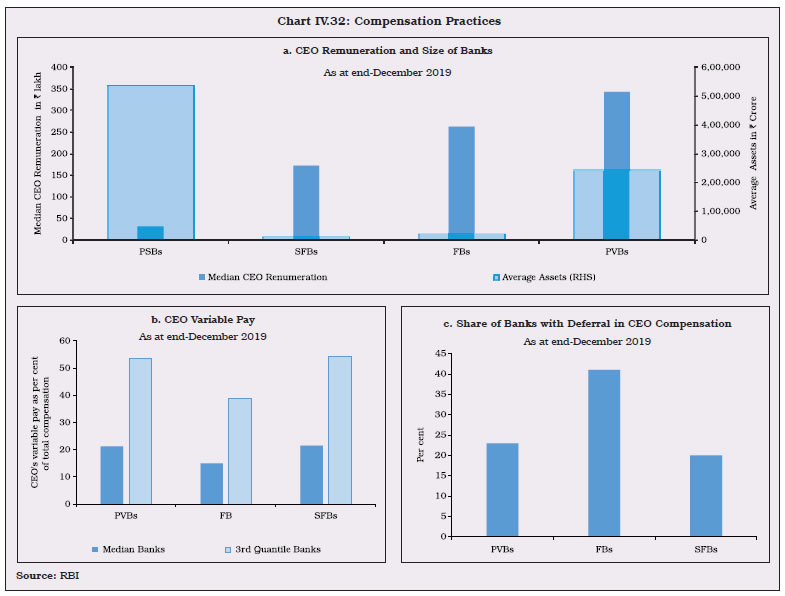

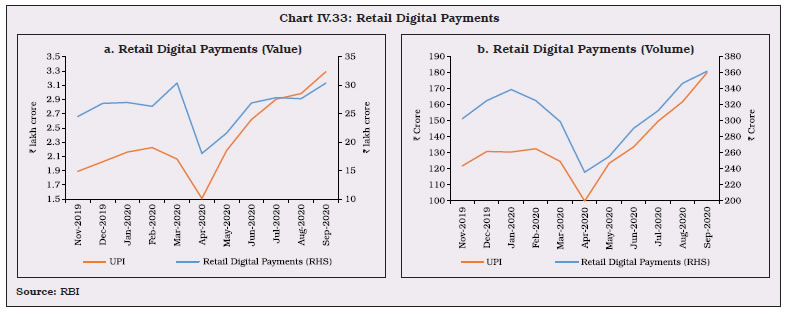

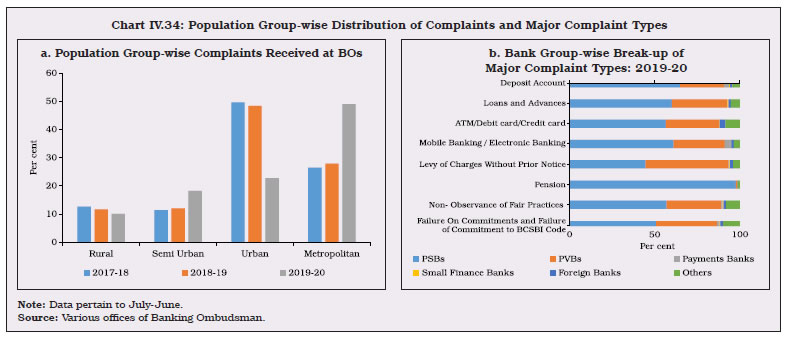

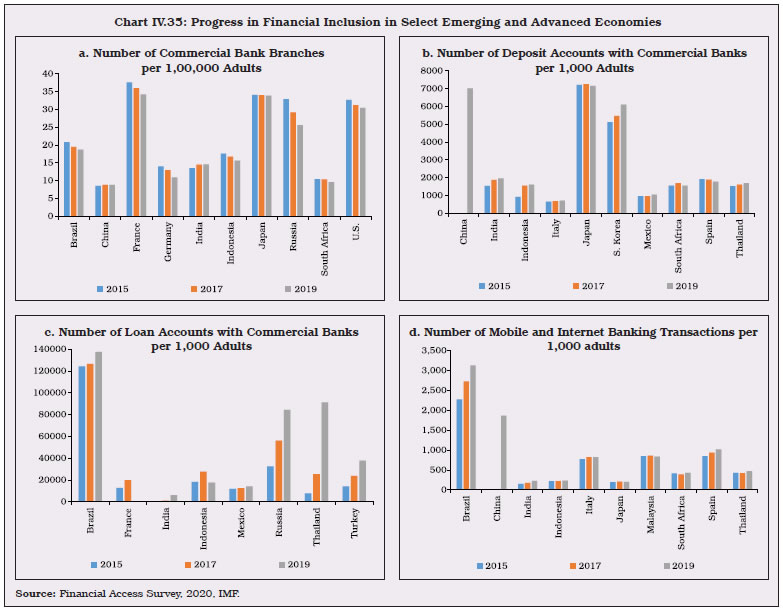

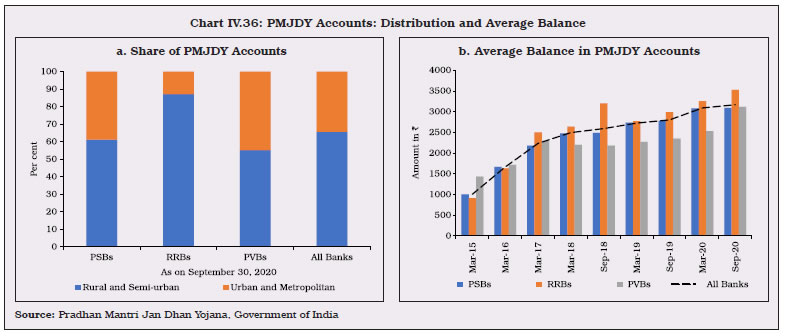

Source: Off-site returns (domestic operations), RBI. | 5.3 Credit to Sensitive Sectors IV.59 Banks’ exposure to the capital market and real estate is reckoned as sensitive in view of risks inherent in fluctuation in prices. While banks generally slowed down such lending. PSBs, in particular, reduced advances against collateral of shares/debentures as a precautionary measure due to excess leveraging of corporates (Chart IV.30 and Appendix Table IV.4). 6. Ownership Pattern in Scheduled Commercial Banks IV.60 Except for Andhra Bank, Punjab and Sind Bank and Syndicate Bank, the Government’s shareholding in other PSBs during 2019-20 either increased (due to recapitalisation) or remained static (Chart IV.31). Amalgamation of 10 PSBs into four, effective from April 1, 2020 brought about significant changes in ownership structure. Government shareholding in Canara Bank, Punjab National Bank, Indian Bank and Union Bank of India significantly increased due to high government share in the merged entities. Currently, the foreign investment limit in PVBs and PSBs is 74 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively. While the maximum foreign shareholding in PSBs was 9.8 per cent, it was more than 50 per cent in five PVBs at end-March 2020. Out of 22 PVBs, only three attracted higher foreign shareholdings during 2019-20 (Appendix Table IV.5). 7. Compensation Practices IV.61 Perverse incentive structures that reward risk-takers for short-term profits, without adequate recognition of long term risks, jeopardise various stakeholders’ interests and have potential to threaten financial stability. Recognising this, especially in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the Reserve Bank introduced its guidelines on compensation practices in 2012. In India, banks which compete in the same market place have different compensation levels and structures (Chart IV.32a). The median variable pay of CEOs in PVBs and SFBs was much less than 50 per cent of their total compensation (Chart IV.32b). Similarly, deferrals in payment of variable pay were found to be infrequent (Chart IV.32c). Therefore, keeping pace with evolving Financial Stability Board’s Principles and Implementation Standards for Sound Compensation Practices, the guidelines were revised in November 2019 and became effective from pay cycles/ performance periods beginning April 1, 2020. These guidelines apply to compensation of Whole Time Directors (WTDs) / Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) / Material Risk Takers (MRTs). The revised guidelines cover, inter alia, specification of the minimum variable pay component, deferral of variable pay and clawback arrangements. These key personnel are required to get at least half of their compensation in the form of variable pay which, in turn, is linked to the bank’s performance. The total variable pay is capped at a maximum of 300 per cent of the fixed pay. Deferral arrangements are required to be implemented for the variable pay of the top executives, regardless of the quantum of pay.  8. Foreign Banks’ Operations in India and Overseas Operations of Indian Banks IV.62 During 2019-20, the number of branches of FBs increased due to scaling up of operations by two wholly owned subsidiaries of FBs (Table IV.21). On the other hand, Indian PSBs continued to reduce their overseas presence for the third consecutive year with a view to rationalising their overseas operations and increasing cost efficiency by shutting down less profitable operations. On the contrary, Indian PVBs increased their overseas presence marginally (Appendix Table IV.6). | Table IV.21: Operations of Foreign Banks in India | | | Foreign banks operating through branches | Foreign banks having representative offices | | No. of Banks | Branches | | March 2016 | 46 | 325 | 39 | | March 2017 | 44 | 295 | 39 | | March 2018 | 45 | 286 | 40 | | March 2019 | 45# | 299# | 37 | | March 2020 | 46# | 308# | 37 | Note: #: Includes two foreign banks namely SBM Bank (India) Limited and DBS Bank India Limited which are operating through Wholly Owned Subsidiary (WOS) mode and their branches.