Sarat Dhal, Purnendu Kumar and Jugnu Ansari*

Economic growth and inflation are often used to characterize economic stability and

monetary or price stability. This study provides an empirical assessment of crucial issues

relating to the linkages of financial stability with economic growth and inflation in the Indian

context. For this purpose, the study uses vector auto-regression (VAR) model comprising

output, inflation, interest rates and a banking sector stability index. The banking stability

index is constructed with capital adequacy, asset quality, management efficiency, earnings and

liquidity (CAMEL) indicators. Our empirical investigation reveals that financial stability on the

one hand and macroeconomic indicators comprising output, inflation and interest rates on the

other hand can share a statistically significant bi-directional Granger block causal relationship.

The impulse response function of the VAR model provides some interesting perspectives. First,

financial stability, growth and inflation could share a medium-longer-term relationship. Second,

enhanced financial stability could be associated with higher growth accompanied by softer

interest rates and without much threat to price stability in the medium to long term. Third,

greater economic stability or higher output growth can enhance financial stability. Fourth,

higher inflation or price instability could adversely affect financial stability. Fifth, financial

stability can contribute to the effectiveness of monetary transmission mechanisms. Finally, with

financial stability, output growth could become more persistent and inflation less persistent.

JEL : E02, E52, G280, E310, O430, C320

Key words : Institutions and macroeconomy, financial stability, monetary transmission,

price stability, economic stability, financial regulation

Introduction

Should financial stability be pursued as a goal of policy? Can

financial stability goal be pursued along with conventional objectives of

policy such as economic stability and monetary stability, which are often

postulated in terms of economic growth and aggregate price inflation, respectively? Whether financial stability could be associated with

adverse or beneficial effects on growth and inflation conditions? Will

financial stability affect growth and inflation differentially over shorter

and medium-longer horizons? Whether financial stability can impinge

on the effectiveness of monetary transmission mechanism? Concerning

the period before the crisis, a key question is whether low monetary

policy rates have spurred risk-taking by banks. These policy issues have

witnessed intense deliberation by economists and authorities following

the series of economic crises since the late 1990s, including the Asian

Crisis and the more recent global crisis. While seeking answers to

these policy questions, a large literature has emerged with a variety of

perspectives on the subject. Low short-term interest rates make riskless

assets less attractive and may result in a search for yield, especially

by those financial institutions with short-term time horizons (Rajan

2005). Acute agency problems in banks, combined with a reliance on

short-term funding, may therefore lead low short-term interest rates—

more than low long-term interest rates—to spur risk-taking (Diamond

and Rajan 2006, 2012). It is generally agreed that financial stability,

unlike economic stability and monetary stability, cannot be defined

appropriately and uniquely. However, the lack of a common perspective

has not dissuaded economists to understand financial stability objective.

Drawing lessons from the distortions to real sectors across the countries

in terms of potential output loss and historic unemployment associated

with financial instability during the crisis periods, economists have

favoured practical considerations. Accordingly, financial stability goal

is pursued with strong, sound and stable institutions, competitive and

effective markets and efficient financial pricing perspectives. After

the global crisis, financial institutions are being subjected to stronger

regulatory framework in line with international standards such as the

Basel prudential norms pertaining to CAMEL indicators. Interestingly,

the Basel prudential norms since their inception in the late 1980s

have witnessed various concerns. Borio et.al. (2001) have expressed

concerns over bank indicators’ pro-cyclicality nature, i.e., the mutually

reinforcing feedback between the financial system and the real economy

that can amplify financial and business cycles. Many studies have

argued that the regulatory framework that existed prior to the global

financial crisis was deficient due to it being largely “microprudential” in nature, aimed at preventing the costly failure of individual financial

institutions (Crockett, 2000; Borio, et.al., 2001; Borio, 2003; Kashyap

and Stein, 2004; Kashyap, et.al., 2008; Brunnermeier et al., 2009; Bank

of England, 2009; French et al., 2010). In this context, it was suggested

that the regulatory framework should focus on ‘macroprudential’

approach to safeguard the financial system as a whole. Accordingly,

the IMF initiated the framework for Financial Soundness Indicators

comprising aggregated micro prudential indicators, financial market

indicators and macroeconomic indicators. In the aftermath of the crisis,

the new Basel III framework has embraced macro prudential approach

with emphasis on systemic risk and stability. The new regulatory

framework has fuelled an enormous debate. In many quarters it is argued

that a strengthening of regulatory framework in terms of higher capital,

liquidity and other requirements as envisaged under Basel III could

pose challenges for macroeconomic stability (Sinha et.al. 2011, Slovik,

Cournède, 2011, Locarno, 2011, BIS, 2010, IIF, 2011). In this context,

studies have recognised that macroeconomic challenges could differ

across developing and developed countries owing to their differences in

financial system and economic structure. Empirical studies, thus, have

proliferated with a focus on cross-country experiences and national

contexts in order to arrive at a generalised perspective on the subject.

In the Indian context, though financial stability has received

considerable attention from the authorities as evident from numerous

speeches of the central bank including Subbarao (2012, 2009), empirical

research on the subject with a focus on seeking answers to the above

questions is almost non-existent. Recently, Ghosh (2011) attempted at

constructing a simple index of banking fragility and identified the factors

affecting the index. Mishra et.al., (2013) provided an analysis of banking

stability as a precursor to financial stability. Both studies, however, did

not provide an analysis of dynamic interaction between macroeconomic

indicators and banking stability and fragility indicators. Thus, we are

motivated for undertaking a study in this direction. Moreover, we are

motivated with some applied perspectives. Firstly, from an operational

perspective, there is a considered view that financial system’s stability

can be attained by focusing on key institutions (Crocket, 2004). In the

Indian context, though financial system has witnessed a significant

diversification owing to reform, the banking sector continues to play a dominant role in three major areas: resource mobilisation

and allocation of such resources to productive sectors, payment and

settlement system, and key player in various financial market segments

such as money, credit, bond and foreign exchange markets. Therefore,

we focus on banking sector stability. Secondly, financial stability and

systemic risk can be postulated through multiple indicators comprising

soundness indicators of banks and financial institutions, indicators of

financial market prices and volatilities and macroeconomic indicators

(Sundarajan et.al., 2002). Illustratively, the soundness of banking

system envisaged under Basel principles, popularly known as CAMEL

approach recognises broadly five indicators: capital adequacy, asset

quality, management efficiency, earnings and liquidity. Studies show

that these indicators can be correlated with each other reflecting upon

banks’ behaviour and macroeconomic conditions. Thus, in line with

macro prudential regulation framework, central banks and numerous

research studies have engaged in constructing aggregated, synthetic

and composite indices for gauging stability of banking and financial

system as a whole (Cheang and Choy, 2010, Cardarelli, et.al. 2008,

Borio and Lowe, 2002, Van den End, 2006, Albulescu, 2010, Geršl and

Hermánek, 2006, BIS, 2001, Illing, and Liu, 2003 and 2006, Das et al.

2005, Misina and Tkacz, 2008, Balakrishnan, et.al. 2009). According to

Sundarajan (2002) and Das et.al. (2005), intuitively, a CAMEL index

aggregates quantitative and qualitative elements of the entire banking

sector and hence has a lot of appeal as a soundness indicator. We take

inspiration from these studies and construct the banking sector stability

index comprising CAMEL indicators for analysing the linkages among

financial stability, growth, inflation and interest rate. Thirdly, for the

empirical analysis, we follow the standard monetary transmission

mechanism literature and utilise the popular vector auto-regression

(VAR) methodology. In this context, we derive insights from Sims

(1992), Braun and Mittnik(1993), Dovern (2010), Kim et.al., (2011)

and Aikman et.al. (2009). These studies have not only highlighted

the inappropriateness of standard approach to monetary transmission

mechanism through a VAR model comprising three variables output,

prices and interest rate but also emphasised upon the usefulness of

an augmented VAR model taking into account banking and financial

stability indicators for meaningful policy analysis.

At the outset, our empirical analysis shows that financial stability

in terms of banking stability can share statistically significant bidirectional

Granger causal relationship with macroeconomic variables.

In terms of impulse response analyses of the VAR model, we found

that greater financial stability could be associated with higher economic

growth without much threat to price stability or inflation in the mediumlonger

horizon. Higher economic progress could lead to greater financial

stability. On the other hand, higher inflation or price instability could

adversely affect financial stability. Financial stability can help monetary

policy in terms of enhanced response of growth and inflation to interest

rate actions.. Also, financial stability can be associated with enhanced

output persistence and lower inflation persistence. In the following, the

paper is presented in five sections. Section II reviews the literature.

Section III discusses methodology and data followed by stylised facts in

Section IV, and empirical analysis in Section V. Section VI concludes.

Section II

Review of Literature

The copious literature on financial stability provides various

macroeconomic and micro foundation perspectives on the linkages

of the financial system and its stability with economic growth, price

stability and monetary policy. In the followings, we bring to the fore

some key perspectives that could justify our study.

II.1 Financial development and economic growth

The literature offers three major perspectives on the relationship

between financial sector development and economic growth. First,

there is the supply-leading theory, where financial development leads

to economic growth (e.g. Bagehot, 1873; King and Levine, 1993;

Schumpeter, 1911; McKinnon, 1973; Shaw, 1973) . Bagehot (1873)

emphasized that the financial system played a critical role in promoting

industrialization in England by facilitating the mobilization of capital.

Three decades later, Schumpeter (1911) recognized Bagehot’s view

and pointed out that financial innovations are facilitated by financial

institutions very actively by identifying and funding productive

investments decisions for future growth. McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1973) recognized the role of the financial sector in the mobilization of

saving and accentuation of capital accumulation, thereby, promoting

economic growth. Second, the demand-following response hypothesis

maintains that economic growth drives the development of the financial

sector. Robinson (1952) argued that financial sector development

follows economic growth. The third view maintains a simultaneous

causal relationship between financial development and economic

growth. Patrick (1966) found that the causal relationship between the

two was not static over the development process. When economic

growth occurs, the demand following response dominates the supply

leading response. But this sequential process was not generic across the

industries or the sectors.

Empirical studies also support the three hypotheses. As an example,

King and Levine (1993) showed a range of financial indicators robustly

and positively correlated with economic growth. Demirguc-Kunt and

Levine (1996) found a positive relationship between stock market,

market microstructure and the development of financial institutions.

Demetriades and Hussein (1996) found finance as a main factor in

the process of economic development. Odedokun (1996) showed

that financial intermediation supported economic growth in most of

the developing countries. Liu et.al. (2006) examined the relationship

between financial development and the source of growth for three

Asian economies, namely, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. They found that

high investment rate accelerated economic growth in Japan, while it did

not lead to better growth performance in Taiwan and Korea, reflecting

upon allocation efficiency in the two countries. Ang (2008) in a study of

Malaysia showed that financial development led to higher output growth

by promoting both private saving and private investment. The study’s

empirical analysis supported the hypothesis that through improved

investment efficiency the growth could be achieved. Odhiambo (2008)

studied the dynamic causal relationship between financial depth and

economic growth in Kenya and found a distinct unidirectional causal

relationship between economic growth to financial development. The

study also concluded that any argument in which financial development

unambiguously leads to economic growth should be treated with

extreme caution.

II.2 Financial stability and economic growth

Until Kindleberger (1978), most studies on the role of the financial

sector in economic progress emphasized the degree of financial

development, usually, measured in terms of the size, depth, openness and

competitiveness of financial institutions. The stability and efficiency of

institutions did not receive much attention, possible due to the intuition

that the competitiveness and growth of financial institutions is due

to their efficiency in operations and resource allocation and optimal

risk management. Kindleberger (1978) and later Minsky (1991) put

forward a viewpoint about financial instability that indicated a negative

influence of financial sector on economic growth. Kindleberger

argued that the loss of confidence and trust in institutions could fuel

disintermediation and institutional closures, and when confidence falls,

investment probably falls too. According to Ang (2008), institutional

instability can also affect the organization of the financial sector and,

consequently, increase the cost of transactions and causes the problems

within the payments system. These transaction costs, which are real

resources leads to misallocation of the resources and hence the rate

of economic growth may suffer. Thus, a sound financial system

instils confidence among savers and investors so that resources can

be effectively mobilized to increase productivity in the economy.

According to Minsky’s (1991) “financial instability hypothesis”,

economic growth encourages the adoption of a riskier behaviour of the

financial institutions and speculative economic activities. Such an overleveraged

situation provides congenial conditions for a crisis caused by

firms default events on their loan repayments due to higher financial

costs. Consequently, higher financial costs and lower income can both

lead to higher delinquency rates and hence the economic recession.

Taking inspiration from Kindleberger (1978) and Minsky (1991),

Eichengreen and Arteta (2000) studied 75 emerging market economies

for the period 1975–1997. They showed that rapid domestic credit

growth was one of the key determinants of emerging market banking

crises. Similarly, Borio and Lowe (2002) using annual data for 34

countries from 1960 to 1999 showed that sustained and rapid credit

growth, combined with large increases in asset prices, increased the

probability of financial instability. Calderon et. al., (2004) on the other hand found that mature institutions and policy credibility allowed

some emerging market economies to implement stabilizing countercyclical

policies. These policies reduced business cycles and economic

fluctuations which led to more predictability power. This predictive

confidence provided a better investment environment that resulted in

more rapid growth.

II.3 Financial stability and inflation

The linkage of a financial system and its stability with inflation

conditions and monetary policy has been a very contentious issue in

the literature. Deliberation in this context entails two crucial issues: the

causal relationship between inflation and financial stability and whether

financial stability should be pursued as a goal of policy, especially by

inflation targeting central banks. Studies provide alternative perspectives

about the channels through which financial stability and inflation can

share a causal relationship (Bordo, 1998, Bordo et.al., 2001).

First, as derived from Fisher (1932 and 1933) and Schwartz (1995,

1997), there is a common perspective that inflation conditions can

interfere with the ability of the financial sector to allocate resources

effectively (Bordo et.al. 2001; Boyd, et.al. 2001; Issing, 2003; Huybens

and Smith, 1998, 1999). This is because inflation increases uncertainties

about future return possibilities. High inflation can be associated with

high inflation volatility and thus, the problem of predicting real returns

and, consequently, a rapid decline in banks’ lending activity to support

investment and economic activities. Bernanke and Gertler (1989) and

Bernanke, et. al. (1999) argued that business cycles could get aggravated

due to interaction between the price instability and frictions in credit

markets. An upward growth trajectory accompanied by high inflation

could cause over-investment and asset price bubbles. Sometimes, the

foundation for financial instability emanates from excessive credit

growth resulted due to realistic return expectations and not for real

investment (Boyd, Levine and Smith, 2001;Huybens and Smith, 1998,

1999). According to Cukierman (1992) banks cannot pass the policy

interest rate, an inflationary control measure of the central banks, as

quickly to their assets as to their liabilities which lead to increasing the

interest rate mismatch and, thus, market risk and financial instability.

Second, some studies emphasize that informational frictions

necessarily play a substantial role only when inflation exceeds certain

critical or threshold level (Azariadas and Smith, 1996, Boyd and Smith,

1998; Choi, et.al.,1996, Huybens and Smith, 1998, 1999; Rousseau,

2009 Rousseau and Wachtel 2002). According to these studies, credit

market frictions may be nonbinding under low inflation environment.

Therefore, low inflation may not distort the flow of information or

interfere with resource allocation and growth. However, beyond the

threshold level of inflation, credit market frictions become binding and

credit rationing intensifies and financial sector performance deteriorates.

When inflation exceeds a threshold, perfect foresight dynamics do not

allow an economy to converge to a steady state displaying either an

active financial system or a high level of real activity. According to Borio

(2006), financial imbalances can develop in a low inflation environment

owing to favourable supply side developments, productivity gains,

globalization and technological advances. In this context, the credibility

of price stability by anchoring inflationary expectations induces greater

stickiness in wages, can delay the inflationary pressures in the short

term but this may lead to unsustainable expansion of aggregate demand

in long run. The low inflation obviates the need of tighten monetary

policy and lead to the development of the imbalances.

II.4 Financial stability and monetary policy

The literature on the relationship of financial stability with

monetary policy and price stability is divided as to whether there are

synergies or a trade-off between them. Schwartz (1995) states that

price stability lead to low risk of interest rate mismatches and low

inflation risk premium. These minimisation of risks resulted from

the accurate prediction of the interest rate due to credibly maintained

prices. The proper risk pricing contribute to financial soundness.

From this perspective, price stability can serve as both necessary and

sufficient conditions for financial stability. Some authors, however, take

a cautious stance in this regard and argue that price stability can be

necessary but not a sufficient condition for achieving financial stability

(Issing, 2008; Padoa-Schioppa, 2002). Mishkin (1996) has argued that

a high interest rate measure to control inflation, could negatively affect

the balance sheets of both banks and firms. Herrero et.al., (2003) have argued that too lax a monetary policy can lead to inflation volatility.

Positive inflation surprises can redistribute real wealth from lenders to

borrowers and negative inflation surprises can have the opposite effect.

A very tight monetary policy may lead to disintermediation and hence

the financial instability. It is argued that a very low inflation levels

resulted from very tight monetary policy may lead to very low interest

rates that would make cash holdings more attractive than interestbearing

bank deposits and hence the disintermediation. Further, a sharp

increase in real interest rates have adverse effects on the balance sheets

of banks and may lead to credit crunch, with adverse consequences for

the financial and real sectors.

Driffill et.al., (2005) provided a theoretical argument that the

central banks interest rate smoothing process might induce a moral

hazard problem and promotes financial institutions to maintain riskier

portfolios. This phenomenon of interest rate smoothing sometimes lead

to indeterminacy of the economy’s rational expectations equilibrium

and inhibits active monetary policy. Thus smoothing may be both

unnecessary and undesirable.

Granville et.al., (2009) examined the relationship between financial

and monetary stability in EMU for a period 1994-2008 and found a long

term pro-cyclical relationship between the two. They suggested that

the interest rate instrument used for inflation targeting is conducive to

financial stability. Dovern et.al., (2010) used a VAR model with Uhlig’s

(2005) sign restrictions approach to understand the interaction between

the banking sector and the macro economy. Banking sectors stress

was captured alternatively through return on equity and loan writeoffs.

The authors found that the level of stress in the banking sector is

strongly affected by monetary policy shocks. Rotondi et. al., (2005)

found that the lagged interest rate influences the estimated policy rules

significantly which in turn promotes the financial stability. Goodfriend

(1987), Smith and Egteren (2004) argued that an aggressive monetary

policy induced macroeconomic stability might lead to riskier behaviour

of commercial banks and other financial institutions due to anticipated

implicit guarantees.

It is challenging task for central banks to maintain monetary and

financial stability simultaneously. The monetary stability in terms of low inflation could confound the imbalances that could lead to higher asset

price volatility which is having serious macroeconomic consequences

(Borio et.al., 2003; Borio and Lowe, 2002). Borio (2006) argued that

policymakers’ credibility in terms of the decisions to manage liquidity

that could result in an unsuccessful monetary policy in the one hand and

decreasing interest rates to increase liquidity could increase inflation on

the other hand. Poloz (2006) argued that successful inflation targeting

might lead to financial volatility and hence the central banks might

better focus on making financial systems more resilient than on trying

to develop more sophisticated policies aimed at reducing financial

volatility.

Kishan and Opiela (2000) argued that small and poorly capitalized

banks exhibit a significantly stronger loan contraction to monetary shocks

compared to large and well-capitalized banks. Kashyap and Stein (1995,

2000), pointed out the asymmetric effects of monetary transmission

under bank lending channel across banks size, capitalization and

liquidity. Monetary policy shocks have a very strong effect on banking

sector distress when the bank’s financial health is poor.

De Graeve, et.al. (2008) argued that an unexpected tightening

of monetary policy increases the probability of distress. The distress

responses have differential impact across the size, capitalization and

ownership of the banks. The authors found investigated that high

capital requirement is a necessary condition for ‘a’ resilient financial

system but not a sufficient condition. This finding supports the

regulators to think about extending the banking regulations beyond the

capital requirement. The nexus among price stability, financial stability

and monetary transmission highlights the crucial need for close coordination

between monetary and regulatory authority.

II.5 Macroeconomic impact of prudential indicators

While numerous studies have assessed the macroeconomic

implications of Basel’s prudential indicators, most have focussed on

capital and liquidity indicators. The Macroeconomic Assessment Group

(MAG, 2010a,b), of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

(BCBS) estimated the transition costs of the new Basel III regulatory

standards in terms of loss in GDP growth and found a modest impact of

capital ratio on aggregate output growth. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) (2010) analyzed the impact of Basel III bank regulatory

requirements on the global economy and found that the aggregate level

of GDP in the United States, euro area and Japan and compared it with

a scenario without regulatory reform. Slovik and Cournede (2011)

studied the medium-term impact of Basel III requirements on aggregate

economic costs for the same economies by combining an accountingbased

framework and found an increase in lending spreads by 0.5 per

cent and cost 0.15 per cent decrease in GDP growth per annum.

Angelini et.al., (2011) endeavoured to assess the long-term

macroeconomic impact of new regulatory standards that is the Basel III

proposal relating to stronger capital and liquidity requirements. They

found that the every percentage point increase in capital and liquidity

requirements could be associated with the model’s decline in steady

state output relative to the baseline.

Gambacorta (2011), using a vector error correction model

(VECM), showed that higher capital and liquidity requirements could

lead to limited negative effects on long-run output and banks earnings.

As compared with the cost of banking crises the economic costs of

Basel III implementation is almost negligible (BCBS, 2010b). The

cost-benefit analysis performed by Locarno (2011), attempted for

a long run and short run assessment for the Italian economy with an

exclusive consideration of capital and liquidity requirements. The

analysis corroborated those of the MAG (2010a,b) and of the Long-

Term Economic Impact Group (BCBS, 2010a). Overall, the economic

impact of the new regulation is small. Eichberger and Summer (2005)

showed that the immediate impact of a capital adequacy constraint

of a bank could lead to decrease of loans to firms and increase in its

interbank position. Banks take higher risk in their lending activity by

granting loans with higher default probability and loss given default

(credit risk), but also by lengthening the loan maturity as in Diamond

and Rajan (2012), i.e., liquidity risk-taking.

Wong et.al., (2010) attempted using VECM a cost-benefit analysis

of higher regulatory capital requirement for Hong Kong and found that

the long-term benefits could be gained in terms of a lower probability of

banking crises while the costs could be associated with a lower output.

Taking a similar cost-benefit approach, Yun et.al., (2011) argued that stronger regulatory requirement could be associated with net long-term

output gains in the U.K .economy. In the similar approach Caggiano

and Calice (2011) assessed the impact of higher regulatory capital

requirements on aggregate output in a panel data model framework for

African economies and found net benefits of higher regulatory capital

requirements in terms of the resilient banking systems.

Section III

Methodology and data

We follow studies on policy transmission mechanism and use

the standard VAR model for our empirical analysis. We refrain from

rehashing the technical details of the VAR model because of its popularity.

For our purpose, we consider two VAR models with common lag-length

(q) a standard VAR model comprising three variables, output (y), price

(p) and interest rate (r) and an augmented VAR model involving the

financial stability indicator (F) as shown here:

VAR(q)s = [y,p,r]

VAR(q)F = [y,p,r,F]

A pertinent question then arises. Why should VAR(q)F be preferred

to VAR(q)s ? In this context we derive insights from numerous studies

(Braun and Mittnik,1993; Dovern et.al, 2010 and Sims, 1992) that have

shown that the standard VAR model comprising output, price and interest

rate may prove inappropriate for policy analysis owing to price puzzles,

forward looking expectations and policy makers processing a variety of

other important information including financial market developments

and the soundness of banks and financial institutions and supply shocks

in deciding the policy stance. From a statistical perspectives, Braun and

Mittnik(1993) showed that a lower dimensional VAR model such as the

VAR(q)s compared with a higher dimensional model VAR(q)F could suffer

from omitted variables bias and misspecification problems, resulting

in biased coefficients in the VAR model and inappropriate impulse

response and forecast error variance decomposition analyses. Dovern

et.al., (2010) cautioned that the VAR model with several variables runs

into the usual degrees-of-freedom problems that eventually haunt all

VAR studies. Therefore, the authors used a slightly augmented VAR

model with output, price, interest rate and one or two banking indicators.

Another issue is whether financial stability indicator should be taken as

an exogenous or endogenous variable in the VAR model. We resolve

the issue through Granger causality and block exogeneity analysis.

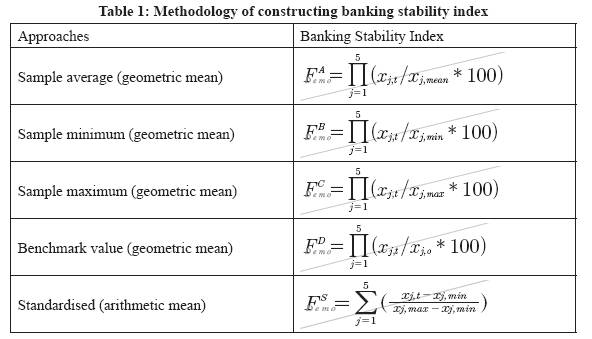

To implement the VAR model with a financial stability indicator,

we constructed an index of banking sectors stability comprising

CAMEL indicators pertaining to the ratio of capital to risk weighted

assets (CRAR), the ratio of gross non-performing loans (NPA) to total

loans and advances reflecting upon asset quality, managerial efficiency

defined in terms of operating expenses to total asset ratio (OEAR),

earnings and profitability measured by return on assets (ROA), and

liquidity ratio, that is, the proportion of liquid assets in total assets.

In this context, we derived insights from Mishra et.al. (2013), Das

et.al. (2005), Cheang and Choy (2009) and Maliszewski (2011)

and experimented with various ways of data mining to construct an

appropriate index using un-weighted (equivalent to equal weighted)

geometric mean and arithmetic mean indices as shown below.

where xj,t is the observed value of a CAMEL indicator j for the period

‘t’ and its sample period average, minimum, maximum and benchmark

values are xj,mean, xj,min, xj,max, and xj,o, respectively. For construction

of the Index FD, we set the benchmark value of xj,o, based on sample

statistics and applied perspectives. Accordingly, we used benchmark

value for capital adequacy ratio at 10 per cent in line with the regulatory requirement and the sample minimum values for other indicators i.e.,

NPA ratio at 2 per cent, operating expenses and provisions ratio at

3 per cent, return on assets at 0.9 per cent, and liquidity ratio 30 per

cent. Furthermore, it is to be noted that empirical CAMEL indicators

can have differential implications for financial stability. Illustratively,

higher CRAR could imply for risk aversion and lower leverage and

thus, improvement in financial stability. Similarly, higher return on

asset and liquidity ratio could be positively associated with financial

stability. However, an increase in the proportion of non-performing

loans in total loans could imply for deterioration of asset quality and

financial instability. Similarly, higher operating cost ratio could imply

for managerial inefficiency and financial instability. Therefore, we used

inverse of NPA and operating expense indicators for constructing their

indices, so that all CAMEL indicators could be linked with financial

stability in the same direction.

As regards data, we collected information from various sources

including the RBI, CMIE, NSE and individual bank websites. We had to

engage in data mining to create consistent series of CAMEL indicators

for a reasonably longer period. Illustratively, we could obtain data for

deriving CAMEL indicators for 39 banks comprising most public sector

banks and some of the old and new private sector banks for the period

1997:Q1 to 2012:Q3. We extended the series to begin from 1995:Q2

by using annual balance sheet data and extrapolation method*. It may

be mentioned that these 39 banks accounted for more than three-fourth

share of total banking sector (Table 2).

Table 2: Share of Sample Banks in the Banking Sector (excluding RRBs) |

(per cent) |

Capital and reserves |

78.6 |

Deposits |

90.1 |

Investment |

84.3 |

Gross loans and advances |

88.6 |

Total assets |

86.6 |

Gross NPAs |

92.0 |

Liquid assets |

86.2 |

Profit |

78.9 |

Section IV

Indian Banking System: Some Stylised Facts

India adopted reform in the early 1990s in the wake of balance of

payment crisis. The reform began with a focus on financial sector in

general and the banking system in particular, as the latter constituted the

principal component of financial system. As part of reform, the banking

sector was granted greater freedom in deposit mobilisation, allocation

of credit and pricing decisions. Competition in the banking system

was promoted by allowing new private sector banks and greater access

of foreign banks. The regulation and supervision system embraced

prudential regulation based on international standards such as Basel

principles. In order to support the banking sector operate effectively and

efficiently, financial markets were developed through newer instruments

and modern technology. Monetary policy framework shifted focus from

direct instruments such as reserve requirement to indirect instrument

such as interest rate and liquidity adjustment facility.

The reform led banking system showed significant improvement

in terms of soundness, operational and allocation efficiency parameters

(Table 3). Illustratively, during 1995-96, the capital adequacy ratio

(CRAR) for the entire banking system stood at 8.7 per cent with 75

banks showing capital adequacy ratio (CRAR) above the regulatory

requirement of 8 per cent and 17 banks showing CRAR below 8 per

cent. In the wake of the Asian crisis, the regulatory capital adequacy

requirement was increased to 9 per cent by March 1998. Since then

banks have shown sustained improvement in meeting the capital

requirement above the stipulated minimum. During 2007-08, the CRAR

for the banking system stood at 13 per cent, 400 basis points higher than

the minimum regulatory requirement. Similarly, asset quality showed

steady improvement as the ratio of gross non-performing loans to gross

advances ratio declined from as high as 17 per cent in 1995-96 to 2.4 per

cent during 2007-08. Managerial efficiency improved with operating

expenses to total assets ratio declining by one percentage point between

1995-96 and 2007-08. The liquidity ratio showed a moderation of 10

percentage points reflecting the impact of SLR reduction to enable

banks for providing increased credit to private sector to support growth, which is reflected in rising trend in credit-deposit ratio (CDR). The

profitability indicator, which showed a volatile trend during the 1990s,

exhibited stability as the return on asset ratio hovered around 1 per

cent during 2002-03 to 2007-08. After the global crisis, bank indicators

have shown some weaknesses especially during the last two years.

There has been moderation in capital adequacy indicator, increase in

NPA ratio, and rising operating expenses reflecting upon the impact of

macroeconomic conditions.

Table 3: CAMEL indicators of the Indian banking sector (%)* |

Year |

CRAR |

GNPAR |

OEAR |

ROA |

LQDR |

CDR |

Growth |

Inflation |

1996 |

8.70 |

17.40 |

2.94 |

0.15 |

|

55.16 |

7.3 |

8.0 |

1997 |

10.40 |

15.70 |

2.85 |

0.66 |

41.24 |

51.26 |

8.0 |

4.6 |

1998 |

11.50 |

14.40 |

2.63 |

0.81 |

41.89 |

50.39 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

1999 |

11.30 |

14.70 |

2.65 |

0.49 |

41.88 |

47.95 |

6.7 |

5.9 |

2000 |

11.10 |

12.70 |

2.48 |

0.66 |

42.25 |

49.26 |

7.6 |

3.3 |

2001 |

11.40 |

11.40 |

2.64 |

0.50 |

42.70 |

49.82 |

4.3 |

7.2 |

2002 |

12.00 |

10.40 |

2.19 |

0.75 |

41.77 |

53.69 |

5.5 |

3.6 |

2003 |

12.70 |

8.80 |

2.24 |

1.00 |

41.60 |

54.53 |

4.0 |

3.4 |

2004 |

12.90 |

7.20 |

2.20 |

1.13 |

42.68 |

54.82 |

8.1 |

5.5 |

2005 |

12.80 |

5.20 |

2.13 |

0.89 |

39.17 |

62.63 |

7.0 |

6.5 |

2006 |

12.30 |

3.48 |

2.13 |

0.88 |

34.46 |

70.07 |

9.5 |

4.4 |

2007 |

12.40 |

2.64 |

1.92 |

0.90 |

32.34 |

73.46 |

9.6 |

6.6 |

2008 |

13.00 |

2.39 |

1.79 |

0.99 |

32.46 |

74.61 |

9.3 |

4.7 |

2009 |

13.20 |

2.45 |

1.71 |

1.01 |

32.55 |

73.83 |

6.7 |

8.1 |

2010 |

13.58 |

2.51 |

1.66 |

0.95 |

32.42 |

73.66 |

8.6 |

3.8 |

2011 |

13.02 |

2.36 |

1.71 |

0.98 |

29.85 |

76.52 |

9.3 |

9.6 |

2012 |

12.94 |

2.94 |

1.65 |

0.98 |

28.94 |

78.63 |

6.2 |

8.9 |

2013 (Sep12) |

12.54 |

3.59 |

1.84 |

1.02 |

30.04 |

74.3 |

5.0 |

|

Note: * Excluding RRBs.

The term CRAR stands for the ratio of capital to risk weighted assets ratio; GNPAR is the ratio

of gross non-performing loans and advances to gross loans and advances; OEAR is the ratio

of operating expenses to total assets ratio; ROA is return on assets (ratio of net profit to total

assets); LQDR is the ratio of liquid assets to total assets and CDR is credit-deposit ratio.

Source: RBI Publications: Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy; Statistical Tables

Relating to Banks in India; Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India. |

Section V

Empirical findings

As common to time series analysis, our empirical analysis begins

with unit root test of economic and financial variables including output,

prices, interest rate and banking sector’s CAMEL indicators and the

financial stability index as shown in Table 4. We find that during the

sample period, the output indicator, real GDP (excluding agriculture

and public administration) in levels after seasonal adjustment and log

transformation, turned out to be non-stationary but stationary process

in terms of first difference and year-on-year growth. Similarly, the

wholesale price index turned non-stationary in level form but stationary

in first difference form. The call money interest rate can be stationary in

level form. Among banking indicators, three of the CAMEL indicators

pertaining to capital adequacy, asset quality and managerial efficiency

were found to be non-stationary variables in levels but stationary

processes in their first differences. On the other hand, return on assets and

liquidity ratio indicators could be stationary in levels. Thus, the index

of financial stability, after seasonal adjustment and log transformation,

turned out to be non-stationary in level but stationary in first difference.

Table 4: Unit root test |

| |

Levels |

First Differences |

ADF Statistic |

Probability |

ADF Statistic |

Probability |

CRAR |

-2.30 |

0.43 |

-8.77 |

0.00 |

GNPAR |

-0.94 |

0.94 |

-4.79 |

0.00 |

OEAR |

-2.31 |

0.42 |

-5.82 |

0.00 |

ROA |

-3.31 |

0.02 |

|

|

LQDR |

-3.29 |

0.03 |

|

|

FA |

-1.84 |

0.67 |

-5.04 |

0.00 |

FB |

-1.84 |

0.67 |

-5.04 |

0.00 |

FC |

-1.84 |

0.67 |

-5.04 |

0.00 |

FD |

-1.84 |

0.67 |

-5.04 |

0.00 |

FS |

-1.12 |

0.92 |

-10.80 |

0.00 |

LY |

-1.16 |

0.91 |

-7.74 |

0.00 |

LP |

0.82 |

1.00 |

-5.70 |

0.00 |

r |

-9.30 |

0.00 |

|

|

Deriving from the unit root analysis, we estimated VAR models

comprising alternative combinations of stationary variables in first

differences. Following the arguments of Dhal (2012), we also include

in the VAR models two exogenous variables pertaining to oil price

shock (first difference of log transformed mineral oil price index) and

food price inflation (first difference of seasonally adjusted and log

transformed food price index) in order to account for the supply shocks.

Table 5 provides summary statistics of these VAR models. Alluding to

our discussion earlier, the VAR models with banking stability index

based on various sample statistics show similar system properties. Thus,

we considered two alternative indicators of stability: the calibrated index

(FD), geometric mean index and the standardised index (FS), arithmetic

mean index. The summary statistics of the VAR models validate the

model with financial stability as compared with the model without

this indicator. Illustratively, consider the two VAR models; VAR1

comprising three variables, namely, the first differences of seasonally

adjusted and log transformed real GDP (dY) and Price Index (dP) and

call money rate (r) and VAR 2 which additionally included the first

difference of seasonally adjusted and log transformed financial stability indicator (dF). The model with financial stability indicator (VAR2), as

compared with the model without financial stability (VAR1), could be

validated in terms of predictive power as reflected in higher value of

log-likelyhood, lower value of the determinant of residual covariance

matrix and better i.e. lower value of information criteria. Thus, for

further analysis we confine our discussion to VAR models based on

banking stability index, FD and FS.

Table 5: Summary Statistics of VAR Models |

|

Model statistics |

VAR Models |

Determinant residual covariance (degrees of freedom adjusted) |

Determinant residual covariance |

Log likelihood |

Akaike information criterion |

Schwarz criterion |

VAR1:

[dy,dp,r] |

1.99E-09 |

7.51E-10 |

406.14 |

-10.84 |

-9.03 |

VAR2:

[dy,dp,r,dFA] |

2.64E-12 |

5.06E-13 |

551.24 |

-14.25 |

-11.31 |

VAR2:

[dy,dp,r,dFB] |

2.64E-12 |

5.05E-13 |

551.26 |

-14.25 |

-11.31 |

VAR2:

[dy,dp,r,dFC] |

2.64E-12 |

5.06E-13 |

551.25 |

-14.25 |

-11.31 |

VAR2:

[dy,dp,r,dFD] |

2.64E-12 |

5.05E-13 |

551.26 |

-14.25 |

-11.31 |

VAR2:

[dy,dp,r,dFS] |

1.02E-11 |

1.96E-12 |

507.25 |

-12.90 |

-9.96 |

Note: output, price and banking stability indices are first difference of seasonally adjusted log transformed series. |

Taking the analysis further, Table 6 provides results for Granger

non-causality block exogeneity test for two VAR models with financial

stability indicator. Results show that financial stability can share

statistically significant bi-directional Granger causal relationship with

macroeconomic variables including output, price and interest rate taken

together. Thus, financial stability can be considered as an endogenous

variable in the VAR model. As regards other variables, output and

interest rate shared significant bi-directional Granger causal relationship

with other variables. The price variable Granger caused other variables.

It was also Granger caused by other variables, albeit, at higher level of

significance at 10 per cent.

Table 6: Granger non-causality block exogeneity test |

| |

Model:

[dY, dP, r, dFD] |

Model:

[dY, dP, r, dFS] |

Granger Causal Relationship |

Chi-square (dof) / [probability] |

Chi-square (dof) / [probability] |

Output growth (dY) does not Granger cause others |

20.10 |

21.45 |

[0.065] |

[0.044] |

Other variables do not cause output (dY) |

34.75 |

34.50 |

[0.001] |

[0.001] |

Inflation (dP) does not Granger causes others |

28.50 |

19.57 |

[0.005] |

[0.076] |

Other variables do not cause inflation (dP) |

25.44 |

22.67 |

[0.013] |

[0.031] |

Interest rate (r) does not Granger causes others |

50.24 |

41.04 |

[0.000] |

[0.000] |

Other variables do not cause interest rate (r) |

31.69 |

32.29 |

[0.002] |

[0.001] |

Financial stability (dF) does not Granger cause others |

32.53 |

30.03 |

[0.001] |

[0.003] |

Other variables do not cause financial stability (dF) |

34.72 |

27.53 |

[0.001] |

[0.006] |

V.1 Impulse response analysis

In a VAR model, impulse responses can vary according to the

order of the variables appearing in the model. Thus, we considered

two types of impulse responses: Choleski decomposition procedure

and generalised impulse responses owing to Peasaran and Shin (1997).

Interestingly, both types of impulse responses appeared to be more

or less similar. Thus, we focus on the Choleski impulse responses of

the VAR model with output, price, interest rate and financial stability

indicator appearing in that order. Since our objective is to assess total

impact of a variable on other variables over shorter and medium-longer

horizons, we considered accumulated responses. The impulse responses

of variables along with asymptotic standard error bands arising from

the VAR model with financial stability indicator are shown in Annex

1 and 2. The impulse response analysis provides answers to some of

the critical issues we raised in the beginning. In this regard, we cull out

the impulse responses (suppressing the associated standard error) as

provided in the Annex for the following discussion.

V.1.1 Impact of financial stability on the macro indicators

We first consider the impact of financial stability on macro

indicators, viz., output growth, inflation and interest rates. From the model

estimated with first differences of output (dY), prices (dP), financial

stability (dF) and interest rate (r) in level, we found that a positive one

standard deviation shock to financial stability could be associated with

positive responses of both output and price variables accompanied by

softer interest rate (Chart 1). It was evident that financial stability could have significant impact on growth over the medium term between 8 to

24 quarters as the impact beyond 24 quarters could not be statistically

significant due to large standard errors. Moreover, financial stability

impact on output growth at about 1.2 per cent at 24-quarters horizon

was substantially higher than the inflation impact at 0.25 per cent. This

implies that financial stability could promote economic growth without

much threat to price stability over medium-longer horizon.

V.1.2 Impact of macroeconomic conditions on financial stability

Second, a positive standard deviation shock to output growth,

implying greater economic stability could be associated with enhanced

financial stability (see Table 7). However, a positive standard deviation

shock to the inflation rate implying price instability could adversely

affect financial stability. In absolute terms, both inflation and growth

shocks had more or less similar impact on financial stability over

the medium to long term horizon. Thus, economic stability and price

stability could promote financial stability.

Table 7: Impulse response of financial stability to macroeconomic shocks(%) |

Period |

Output Impact |

Price Impact |

Interest rate Impact |

1 |

0.62 |

-1.32 |

0.14 |

| |

(1.13) |

(1.13) |

(1.12) |

4 |

6.09 |

-4.48 |

1.46 |

| |

(2.19) |

(1.77) |

(1.76) |

8 |

5.67 |

-5.30 |

-0.09 |

| |

(3.10) |

(2.66) |

(2.40) |

12 |

6.29 |

-5.84 |

-1.04 |

| |

(4.04) |

(3.12) |

(3.12) |

20 |

6.95 |

-6.59 |

-1.87 |

| |

(5.47) |

(4.15) |

(4.43) |

40 |

7.31 |

-7.02 |

-2.38 |

| |

(6.80) |

(5.25) |

(5.83) |

60 |

7.35 |

-7.06 |

-2.43 |

|

(7.02) |

(5.44) |

(6.07) |

Figures in parentheses indicate asymptotic standard errors. |

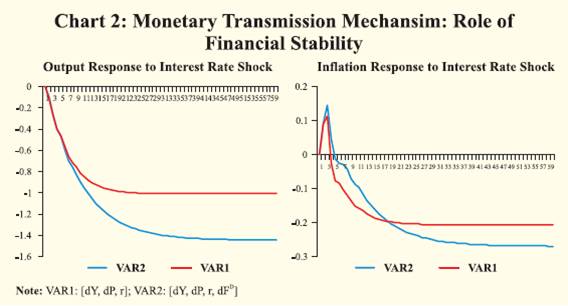

V.1.3 Effectiveness of monetary transmission: Role of financial stability

Thirdly, a positive standard deviation shock to interest rate,

reflecting upon tight monetary policy stance, can contain inflation but

adversely affect growth and financial stability. However, in terms of size, its impact on financial stability could be much lower than growth

and inflation effects. A comparative picture of the output and inflation

responses to call money rate shock arising from the model without

financial stability (VAR1) and the model with financial stability (VAR2)

provides insights about the role of financial stability in influencing the

effectiveness of monetary policy (see Chart 2). In this case, we find that

financial stability does not affect effectiveness of monetary transmission

mechanism in the shorter horizon. However, in medium and longer

horizons, output and inflation responses to monetary policy stance

could be a sizably enhanced due to financial stability. This is evident

from output and inflation responses to the call money rate shock arising

from the model with financial stability being 30 to 40 per cent higher

than the model without financial stability. Thus, financial stability can

contribute to medium-longer term effectiveness of monetary policy in

macroeconomic stabilisation.

V.1.4 Persistence of Growth and Inflation: Role of Financial Stability

Fourthly, a comparison between the two VAR models with and

without financial stability indicator also shows the changes in the nature

of output and inflation persistence to their own shocks (see Chart 3).

With the presence of financial stability indicator, output shock could

be more persistent and inflation less persistent over medium and longer

horizon. From a comparative perspective between output and inflation,

the increase in persistence of output is much higher than the moderation

of persistence in inflation owing to financial stability. Following Cochrane (1988) and Campbell and Mankiew (1987), persistence in

economic time series can reflect on the importance of their permanent

component relative to transitory component. Accordingly, the role of

financial stability in influencing output and inflation persistence can be

interpreted.

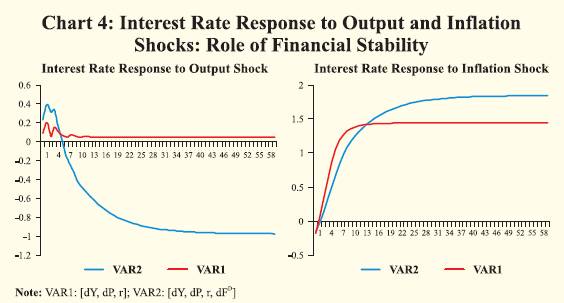

V.1.5 Interest rate’s response to growth and inflation: Role of financial

stability

The impulse response analysis provides insights about how interest

rate would react to growth and inflation shocks with and without

the presence of financial stability in the VAR model (see Chart 4).

Illustratively, in the model without financial stability (VAR1), interest

rate reacts positively to positive shocks to both output and inflation

indicators, though the interest rate’s response to price shocks is

substantially higher than its response to output shock. This finding could

be attributed to greater sensitiveness of policy rate to price stability

than economic growth. However, in the presence of financial stability,

i.e., VAR2 model, interest rate continues to react positively to inflation

shock and such reaction is enhanced in the medium term. On the other

hand, in response to output shock, interest rate reacts positively, albeit

marginally, in the short run but negatively and substantially in the

medium-longer horizon as compared with its short run response. This

implies that financial stability could facilitate softer policy to promote

growth and tighter policy to achieve price stability in the mediumlonger

horizon.

Section VI

Conclusion

In this study, we endeavoured at providing applied perspectives

on some crucial policy issues relating to the relationship of financial

stability with growth and inflation which characterise economic stability

and monetary stability objectives. We experimented with aggregate

banking sector soundness index comprising prudential CAMEL

indicators based on quarterly data for a sample of 39 banks comprising

all public sector banks and major old and new private sector banks.

We used an augmented VAR model for analysing the transmission

mechanism. Our empirical investigation brought to the fore some

interesting perspectives. First, financial stability, growth and inflation

could share a medium to longer term relationship, and this finding is

in line with several studies. Second, financial stability can promote

growth without posing much threat to price stability. Third, financial

stability can enhance the effectiveness of monetary transmission

mechanism. Fourth, economic growth can have positive influence on

financial stability. But inflation can adversely affect financial stability.

Finally, with financial stability, growth could be more persistent and

inflation less persistent. Since persistence could imply for permanent

component, we can infer that financial stability will be beneficial for

growth and price stability. Thus, we conclude that financial stability

goal can be pursued along with conventional objectives in the Indian

context.

These findings are expected to be useful for policy purposes.

Going forward, research on the subject could be extended inter alia

through two major directions. First, attempts can be made towards

constructing a quarterly index of financial stability index comprising

CAMEL indicators and financial market indicators for reasonably

longer period to examine further perspectives on the subject. Second,

on the methodological front, VAR models with Bayesian analysis and

sign restrictions on impulse response and structural identification could

be useful. In addition, attempts can be made to use the VECM to explore

long-run relationship between financial stability and macroeconomic

indicators.

References

Ang, J. B. 2008. “What are the mechanisms linking financial development

and economic growth in Malaysia?” Economic Modelling, 25: 38-53.

Azariadas, C., Smith, B. 1996. “Private Information, Money and

Growth: Indeterminacies, Fluctuations, and the Mundell-Tobin effect.”

Journal of Economic Growth, 1: 309-322.

Bagehot, W. 1873. Lombard Street: A Description of the Money market.

Irwin, Homewood, Ilinois.

Bank for International Settlement. 2010. “Assessing the macroeconomic

impact of transition to stronger capital and liquidity requirement.”

Final Report, BASEL.

Bernanke, B. S., Kuttner, K. N. 2005. “What Explains the Stock

Market’s Reaction to Federal Reserve Policy?” Journal of Finance,

60(3):1221-1257.

Bordo, M. D., Murshid, A. P. 2000. “Are Financial Crises Becoming

Increasingly More Contagious? What is the Historical Evidence on

Contagion?” NBER Working Papers 7900.

Borio, C. 2003. “Towards a macroprudential framework for financial

supervision and regulation?” CESifo Economic Studies, 49:181-216.

Borio, C., English, B., Filardo, A. 2003. “A tale of two perspectives:

old or new challenges for monetary policy?” BIS Working Papers 127.

Borio, C., Lowe, P. 2002. “Asset prices, financial and monetary stability:

exploring the nexus.” BIS Working Papers 114.

Borio, Claudio. 2006. “Monetary and financial stability: Here to stay?”

Journal of Banking & Finance, 30:3407-3414.

Boyd, J. H., Smith, B. D. 1998. “Capital market imperfections in a

monetary growth model”, Economic Theory, 11, 241-273.

Boyd, J. H., Levine, R., Smith, B. D. 2001. “The impact of inflation

on “financial sector performance.” Journal of Monetary Economics,

47:221-248.

Braun, P. A., Mittnik, S. 1993. “Mis-specifications in Vector

Autoregressions and Their Effects on Impulse Responses and Variance

Decompositions.” Journal of Econometrics, 59:319-341.

Calderon, C., Duncan, R., Schmidt-Hebbel, K. 2004. “The role of

credibility in the cyclical properties of macroeconomic policies:

Evidence for emerging markets.” Review of World Economics,

140(4):613-633.

Calvo, G. 1997. “Capital flows and macroeconomic management:

Tequila lesson.” International Journal of Finance and Economics,

1(3):207-223.

Campbell, John Y., and N. Gregory Mankiw. 1987. “Permanent and

transitory components in macroeconomic fluctuations.” American

Economic Review, 77(2): 111-117.

Cevik, E. I., Dibooglu, S., Kenc, T. 2013. “Measuring financial stress in

Turkey”, Journal of Policy Modeling, 35: 370-383.

Choi, S., Boyd, J., Smith, B. 1996. “Inflation, financial markets, and

capital formation”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 78: 9-35.

Cochrane, John H. 1988. “How Big is the Random Walk in GNP?”,

Journal of Political Economy, 96(5):893-920.

Cook, T., Hahn, T. 1989. “Federal Reserve Information and the

Behaviour of Interest Rates”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 24:331-

351.

Cukierman. 1992. Central Bank Strategy, Credibility and Independence:

Theory and Evidence. Cambridge, Mass, MIT press.

Demetriades, P. and Hussein, K. 1996. “Does Financial Development

Cause Economic Growth?: Evidence for 16 Countries”, Journal of

Development Economics, 51:387-411.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Levine, R. 1996. “Stock Market Development

and Financial Intermediaries: Stylized Facts”, World Bank Economic

Review, World Bank Group, 10(2):291-321.

Diamond, D. W., and R. G. Rajan. 2006. “Money in a Theory of

Banking.” American Economic Review, 96 (1): 30–53.

———. 2012. “Illiquid Banks, Financial Stability, and Interest Rate

Policy.” Journal of Political Economy,120 (3): 552–91.

Dovern, J., Meier, C., Vilsmeier, J. 2010. “How resilient is the German

banking system to macroeconomic shocks?” Journal of Banking &

Finance, 34:1839-1848.

Driffill, J., Rotondi, Z., Savona, P., Zazzara, C. (2006): “Monetary

policy and financial stability: what role for the futures market?”, Journal

Financial Stability, 2, 95–112.

Eichberger, J., Summer, M. 2005. “Bank Capital, Liquidity, and Systemic

Risk”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2):547-555.

Eichengreen, B., Arteta, C. 2000. “Banking Crises in Emerging

Markets: Presumptions and Evidence”, Center for International and

Development Economics Research Working Paper No. 115.

Gambacorta, L.2011. “Do Bank Capital and Liquidity Affect Real

Economic Activity in the Long Run? A VECM Analysis for the US”,

Economic Notes, 40(3):75-91.

Ghosh, S. 2011. “A Simple Index of Banking Fragility: application to

Indian Data”, Journal of Risk Finance, 12(2):112-120.

Goodfriend, M. 1987. “Interest rate smoothing and price level trendstationarity”,

Journal of Monetary Economics” 19:335-348.

Graeve, F. De, Kick, T., Koetter, M. 2008. “Monetary policy and

financial (in)stability: An integrated micro–macro approach”, Journal

of Financial Stability, 4(3):205-231.

Granville, B., Mallick, S. 2009. “Monetary and financial stability in the

euro area: Pro-cyclicality versus trade-off”, Journal of International

Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 19(4):662-674.

Herrero, A. G., Rio, P. 2003. “Financial Stability and the Design of

Monetary Policy”, Banco de Espana Working Paper No. 0315.

Huybens, E., Smith, B. 1998. “Financial market frictions, monetary

policy, and capital accumulation in a small open economy”, Journal of

Economic Theory, 81:353-400.

Huybens, E., Smith, B. 1999. “Inflation, financial markets, and longrun

real activity”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 43:283-315.

Institute for International Finance (IIF). 2011. “The Cumulative

Impact on the Global Economy of Changes in the Financial regulatory

Framework”, Final Report, September.

Issing, O. 2003. “Monetary and Financial Stability: Is there a Tradeoff?”,

BIS Working Paper No. 18.

Kashyap, A.K., Stein, J.C. 1995. “The impact of monetary policy on

bank balance sheets”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public

Policy, 42:151-195.

Kashyap, A.K., Stein, J.C. 2000. “What do a million observations on

banks say about the transmission of monetary policy?”, American

Economic Review, 90 (3):407–428.

Kindleberger, C.P. 1978. Manias, Panics and Crashes. Basic Books,

New York.

King, R., Levine, R. 1993. “Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be

right”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108:717-737.

Kishan, R.P., Opiela, T.P. 2000. “Bank Size, bank capital, and the bank

lending channel”, Journal of Money ,Credit and Banking. 32(1):121-

141.

Kuttner, K. N. 2001. “Monetary policy surprises and interest rates:

Evidence from the Fed funds futures market”, Journal of Monetary

Economics, 47(3):523-544.

Liu, W., Hsu, C. 2006. “Role of financial development in economic

growth: experiences of Taiwan, Korea, and Japan”, Journal of Asian

Economics, 17:667-690.

Locarno, A. 2011. “The macroeconomic impact of Basel III on the

Italian economy”, Occasional Papers No. 88, Banca D’ Italia.

McKinnon, R. 1973. “Money and Capital in Economic Development”,

Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

Minsky, H. 1991. The Financial Instability Hypothesis: A Clarification.

in: M. Feldstein, ed., The Risk of Economic Crisis, University of

Chicago Press: Chicago, 158-70.

Mishkin, F. S. 1996. “The Channels of Monetary Transmission: Lessons

for Monetary Policy”, NBER Working Paper No. 5464.

Odedokun, M.O. 1996. “Alternative Econometric Approaches for

Analyzing the Role of the Financial Sector in Economic Growth: Time

Series Evidence from LDCs”, Journal of Development Economics,

50(1):119-146.

Padoa-Schioppa, T. 2002. “Central Banks and Financial Stability:

Exploring a Land in Between”, 2nd ECB Central Banking Conference.

Patrick, H. 1966. “Financial Development and Economic Growth in

Underdeveloped Countries”, Economic Development and Cultural

Change. 14(2):174-189.

Poloz, S. S. 2006. “Financial stability: A worthy goal, but how feasible?”,

Journal of Banking & Finance, 30: 3423-3427.

Rajan, R. G. 2005. “Has Financial Development Made the World

Riskier?” NBER Working Paper No. 11728.

Robinson, J. 1952. The Generalisation of The General Theory in: The

Rate of Interest and other Essays. McMillian, London.

Rotondi, Z. and Giacomo V. 2005. “The Fed’s reaction to asset prices”,

Journal of Macroeconomics, 30: 428-443.

Rousseau, P. L., Wachtel, P. 2002. “Inflation thresholds and the finance–

growth nexus”, Journal of International Money and Finance, 21:777-

793.

Rousseau, P. L., Yilmazkuday, H. 2009. “Inflation, financial

development, and growth: A trilateral analysis”, Economic Systems,

33:310-324.

Rudebusch, G. D. 2005. “Monetary Policy Inertia: Fact or Fiction?”,

International Journal of Central Banking, 2(4):85-135.

Schumpeter, J.A. 1911. The Theory of Economic Development. Oxford

University Press, Oxford.

Schwartz, A. J. 1995. “Why Financial Stability Depends on Price

Stability”, Economic Affairs, 21-25.

Shaw, E. 1973. Financial deepening in economic development. Oxford

University Press, New York.

Sims, C. A. 1992. “Interpreting the macroeconomic time series facts:

The effects of monetary policy”, European Economic Review, 36:974-

1011.

Sinha, A., Kumar, R., and Dhal, S.C. 2011. “Financial Sector Regulation

and Implications for Growth”, CAFRAL-BIS International Conference

on Financial Sector Regulation for Growth, Equity and Financial

Stability in the post-crisis world.” BIS Paper No. 62.

Slovik, P. and B. Cournède. 2011. “Macroeconomic Impact of Basel

III”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 844, OECD.

Smith, R.T., Egteren, V. H. 2004. “Interest Rate Smoothing and

Financial Stability”, Working paper, University of Alberta, Edmonton,

Canada.

Subbarao, D. 2011. “Price stability, financial stability and sovereign

debt sustainability policy challenges from the New Trilemma”, Second

International Research Conference of the Reserve Bank of India,

Mumbai, February 2012.

Subbarao, D. 2009. “Financial stability - issues and challenges”,

FICCI-IBA Annual Conference on “Global Banking: Paradigm Shift”,

organised jointly by FICCI and IBA, Mumbai, 10 September 2009.

|