Preface Finance is a powerful intervention for economic development. Access to finance, especially for the poor, is empowering because financial exclusion often leads to broader social exclusion. Yet, formal finance does not appear to have adequately permeated vast segments of our society, although progress is being made. To advance the process, the Reserve Bank has granted ‘in principle’ approval to a multitude of players in the financial eco-system to establish Payments Banks and Small Finance Banks. The recently announced Jan Dhan Yojana by the government marks a landmark in the quest for universal financial access. The government is also focusing on paying benefits directly into these accounts. This will ensure that a big chunk of the accounts opened under various schemes, which are presently dormant, witness ‘movement’, thereby integrating access with use. These are very heartening developments. Several Committees in the recent past have opined on our quest for a more inclusive financial regime. The thrust of their recommendations was towards having an enabling regulatory framework, improving delivery systems and exploiting its possible synergies. At the Reserve Bank Conference on Financial Inclusion in April 2015, the Hon’ble Prime Minister urged the Reserve Bank to take the lead in encouraging financial institutions to set concrete targets for financial inclusion to help transform the quality of life of the poor. Against this backdrop, this Committee on Medium-term Path on Financial Inclusion (CMPFI) was set up to devise a measurable and monitorable action plan for financial inclusion that encompasses both households and small businesses. The Committee sets a much wider vision of financial inclusion as ‘convenient‘ access to a set a basic formal financial products and services that should include savings, remittance, credit, government-supported insurance and pension products to small and marginal farmers and low-income households at reasonable cost with adequate protection progressively supplemented by social cash transfer besides increasing the access for micro and small enterprises to formal finance with greater reliance on technology to cut costs and improve service delivery, such that by 2021 over 90 per cent of the hitherto underserved sections of society become active stakeholders in economic progress empowered by formal finance. Thus, the financial inclusion initiative as envisaged by the Committee is much broader in scope, going beyond the traditional domain of the Reserve Bank. Meaningful financial inclusion is not feasible without government-to-person (G2P) social cash transfer. There is also an opportunity to usher in next-generation reforms by replacing agricultural input subsidy with income support, which increases the personal disposable surplus of the poor on a regular basis and could place the inclusion effort on a solid foundation. With the Jan Dhan, Aadhaar and Mobile (JAM)) trinity taking hold, there is an ideal opportunity to seamlessly integrate access and use and, in the process, ensure that leakages in financial transfers are substantially lowered. Innovative delivery channels, such as mobile wallet and e-money coupled with regulatory changes to allow interoperability across banks and non-banks, seem to hold the key to a more efficient payment system and reduce the fascination for cash. Banks need to integrate the Business Correspondent (BC) model into their business strategy and with help from technology can develop a low-cost, reliable, ‘last mile’ delivery channel that could win the trust of the common person. Biometric identification coupled with the provision of credit information to credit bureaus can help build a more robust credit system that can then be used as the basis for obtaining loans at reasonable costs while avoiding the pitfalls of over-indebtedness. For micro and small enterprises, professionals who can evaluate the creditworthiness of these firms by acting as intermediaries with the bank can help alleviate the significant credit gap in this sector. In agriculture, millions of small farmers live on the precipice, starved of credit. In the absence of bold structural reforms of land digitisation and tenancy certification to enable credit to the tiller, the problem is likely to persist. Agricultural distress can only be addressed satisfactorily by instituting universal crop insurance for small and marginal farmers at a heavily subsidised rate by the government, the money for which can be funded by doing away with the current interest subsidy scheme that has distorted the agricultural credit system and seems to have impeded long-term investment. The issue of gender exclusion can be addressed by a welfare scheme for the girl child linked to education. Similarly, exclusion based on beliefs can be explored by delivering simple interest free financial products through a separate window in conventional banks. While financial products have their benefits, there is a clear danger of mis-selling, which could damage marginalised segments who have an uncertain cash flow. Efforts on financial education need to be strengthened, including product-driven financial literacy so that the poor are not short-changed. Grievance redressal for customer complaints in banks needs some imaginative thinking. The overall governance structure would have to be more business-like, focused on delivery. The Committee believes that addressing significant pockets of exclusion, the adoption of technology and allowing multiple models and partnerships to emerge could effectively buttress the cause of financial inclusion. In its work, the Committee benefited from several quarters. I thank Dr. C. Rangarajan, Dr. Bimal Jalan, Dr. Y.V. Reddy and Dr. D. Subbarao, all former Governors of the Reserve Bank, for their words of wisdom, as this is an issue that engaged the attention of the Reserve Bank for several decades and continues to do so. I thank Ms. Anjuly Chib Duggal, Secretary and Shri Rajesh Aggarwal, Joint Secretary, Department of Financial Services, Government of India for sharing their insights on this issue. We thank Shri H.R. Khan, Shri R. Gandhi and Shri S.S. Mundra, Deputy Governors and Shri U.S. Paliwal, Executive Director for sharing their thoughts. Our gratitude to Dr. Raghuram G. Rajan, Governor for his vision and for giving us the responsibility. Finally, I thank the members of the Committee—Prof. Ashok Gulati, Dr. Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Mr. A. P. Hota, Mr. Paresh Sukthankar, Mr. Kishor P. Kharat, Mr. Subrata Gupta, Dr. Pawan Bakhshi, Mr. A. Udgata, Mr. Sudarshan Sen, Mr. Arun Pasricha, Mrs. Nanda S. Dave and Dr. Y.K. Gupta—for many evenings of stimulating discussion that make the report what it is. My special thanks to Dr. Saibal Ghosh for putting up with our endless demands for technical finesse. “…and miles to go before I sleep”, said Robert Frost, the celebrated American poet. The task of financial inclusion is onerous, but is, by no means, insurmountable. It is hoped that the Report will provide inputs and ideas for policymakers to drive forward the financial inclusion agenda, and make us a more efficiently financially included society. Deepak Mohanty

Acknowledgements The Report of the Committee on Medium-term Path on Financial Inclusion (CMPFI) was made possible with the support and contributions of many individuals and organisations. The Committee would like to gratefully acknowledge representatives of credit information companies, representatives of PPIs/Telcos, representatives of microfinance institutions, officials of state-level bankers’ committees, offices of lead banks in various states, BC agents and bank officials for providing insights from the ground. The Committee appreciates the support provided by the regional offices of the Reserve Bank at Chennai, Hyderabad, Guwahati and Kolkata in organising stakeholder meetings and conducting quick studies. The Committee places on record its appreciation of the valuable contributions from officials from the State Bank of India, Shri G.K. Kansal, Chief General Manager and Shri J. K. Thakkar, General Manager who were special invitees to the Committee meetings. In order to provide technical support, an Internal Working Group was ably led by Shri T.V. Rao, General Manager, supported by Shri Sanjay Singh, Assistant Adviser, Shri B.S Sonawane, Assistant General Manager, Shri Radheshyam Verma, Research Officer, Shri Sachin Sharma, Manager, and Ms. C. SreeRangini, Manager. The Committee also places on record the valuable contributions from Shri Jose J. Kattoor and Shri R.K. Moolchandani, General Managers, Shri Prabhat Kumar, Deputy General Manager, Ms. Mary Kochuvaried, Assistant General Manager and Smt. Manisha Kale, Shri Swapnil Kumar Shanu, Shri S. Subramanian, Ms. Chaitanya Devi and Shri Gajendra Sahu, Managers. The Committee would like to commend the enormous hard work put in by the Secretariat team from the Financial Inclusion and Development Department (FIDD) led by Shri Bipin S. Nair, Assistant General Manager supported by Smt. Mruga M. Paranjape, Shri Vergese Mathews, Managers, Shri Deepak H. Waghela, Assistant Manager, Shri Kumud Kumar and Shri Vikas Saini. The Committee also places on record the excellent assistance provided by Smt. S. Mane and Shri S.S. Jogale. The Committee thanks Dr. A.S. Ramasastri, Dr. Gautam Chatterjee, Smt. Balbir Kaur, Smt. Lily Vadera and Smt. Jaya Mohanty for their suggestions. Finally, the Committee would like to thank other institutions and members of the public who gave their comments and suggestions.

List of Abbreviations | AIC | Agriculture Insurance Company | | AIDIS | All-India Debt and Investment Survey | | ANBC | Adjusted Net Banking Credit | | AP | Andhra Pradesh | | APB | Aadhaar Payment Bridge | | ATM | Automated Teller Machine | | AWS | Automated Weather Station | | BC | Business Correspondent | | BCA | Business Correspondent Agent | | BCSBI | Banking Codes and Standards Board of India | | BDC | Benazir Debit Card | | BISP | Benazir Income Support Programme | | BNM | Bank Negara Malaysia | | BOS | Banking Ombudsman Scheme | | BPL | Below Poverty Line | | BRICS | Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa | | BSBDA | Basic Savings Bank Deposit Account | | BSE | Bombay Stock Exchange | | CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate | | CBS | Core Banking Solution | | CBSE | Central Board for Secondary Education | | CD Ratio | Credit-Deposit Ratio | | CEP | Consumer Education and Protection | | CEPD | Consumer Education and Protection Department | | CERC | Central Electricity Regulatory Commission | | CGAP | Consultative Group to Assist the Poor | | CGA | Credit Guarantee Agency | | CGCMB | Credit Guarantee Corporation Malaysia Berhad | | CGC | Commercial Guarantee Company | | CGS | Credit Guarantee Scheme | | CGTMSE | Credit Guarantee Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises | | CIC | Credit Information Company | | CIN | Corporate Identity Number | | CP | Consumer Protection | | CRAR | Capital to Risk Weighted Assets Ratio | | CSP | Customer Service Point | | CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility | | CSS | Centrally Sponsored Scheme | | DAR | Debt-to-Asset Ratio | | DBT | Direct Benefit Transfer | | DCC | District Consultative Committee | | DCCB | District Central Co-operative Bank | | e-KYC | Electronic – Know Your Customer | | EMDE | Emerging Market and Developing Economy | | E-Money | Electronic Money | | FCP | Financial Consumer Protection | | FIDD | Financial Inclusion and Development Department | | FII | Financial Inclusion Insights | | FINDEX | Financial Inclusion Index | | FIP | Financial Inclusion Plans | | FLCC | Financial Literacy Counselling Centre | | FLC | Financial Literacy Centre | | FSA | Financial Services Authority | | FSB | Financial Stability Board | | FSDC | Financial Stability and Development Council | | FSDC-SC | Financial Stability and Development Council – Sub Committee | | FY | Financial Year | | G20 | Group of 20 | | G2P | Government-to-Person | | GCA | Gross Cropped Area | | GCC | General Credit Card | | GDP | Gross Domestic Product | | GIS | Geographical Information System | | GOI | Government of India | | GPS | Global Positioning System | | GSM | Global System for Mobile | | GVA | Gross Value Added | | HQLA | High Quality Liquid Asset | | IBA | Indian Banks’ Association | | ICC | Integrated Contact Centre | | ICT | Information and Communication Technology | | IDB | Islamic Development Bank | | IFSB | Islamic Financial Services Board | | IMF | International Monetary Fund | | INR | Indian Rupee | | IOI | Incidence of Indebtedness | | JAM | Jan Dhan Aadhaar Mobile | | JLG | Joint Liability Group | | KCC | Kisan Credit Card | | KFH | Kuwait Finance House | | KODIT | Korea Credit Guarantee Fund | | KRW | South Korean Won | | LBS | Lead Bank Scheme | | LCR | Liquidity Coverage Ratio | | LPG | Liquid Petroleum Gas | | MCGA | Municipal Credit Guarantee Agency | | MENA | Middle East and North Africa | | ME | Medium Enterprise | | MFI | Micro-Finance Institution | | MGF | Mutual Guarantee Funds | | MIT | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | | MLI | Member Lending Institute | | MNREGA | Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act | | MSE | Micro and Small Enterprise | | MSME | Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise | | MUDRA | Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency Ltd | | NABARD | National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development | | NBFC | Non-Banking Financial Company | | NDP | Net Domestic Product | | NEFT | National Electronic Funds Transfer | | NGO | Non-Government Organisation | | NIC | National Informatics Centre | | NIPFP | National Institute of Public Finance and Policy | | NPCI | National Payments Corporation of India | | NPL | National Priorities List | | NRLM | National Rural Livelihood Mission | | NSA | Net Sown Area | | NSDP | Net State Domestic Product | | NSFE | National Strategy for Financial Education | | NSSO | National Sample Survey Organisation | | NUUP | National Unified USSD Platform | | O&M | Operation and Maintenance | | OBO | Office of Banking Ombudsman | | OIC | Organisation for Islamic Cooperation | | PACS | Primary Agriculture Credit Society | | PA-HAL | Pratyaksha Hastaantarit Labh | | PAN | Permanent Account Number | | PCGA | Provincial Credit Re-Guarantee Agency | | PCNSDP | Per Capita Net State Domestic Product | | PLS | Profit and Loss Sharing | | PMJDY | Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana | | PMRY | Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Yojana | | PoS | Point-of-Sale | | PPI | Prepaid Payment Instrument | | PPP | Purchasing Power Parity | | PSIA | Profit Sharing Investment Account | | PSL | Priority Sector Lending | | PTC | Pass-Through Certificate | | RAROC | Risk Adjusted Return on Capital | | RBI | Reserve Bank of India | | SLR | Statutory Liquidity Ratio | | SME | Small and Medium Enterprise | | SPV | Special Purpose Vehicle | | RIDF | Rural Infrastructure Development Fund | | RoR | Record of Rights | | RRB | Regional Rural Bank | | RSETI | Rural Self Employment Training Institute | | SBLP | SHG Bank Linkage Programme | | SCB | Scheduled Commercial Bank | | SERP | Society for Elimination of Rural Poverty | | SGSRY | Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rozgar Yojana | | SGSY | Swarnajayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana | | SHG | Self-Help Group | | SIDBI | Small Industries Development Bank of India | | SIM | Subscriber Identity Module | | SLBC | State Level Bankers’ Committee | | StCBs | State Co-operative Banks | | T&D | Transmission and Distribution | | TGFIL | Technical Group on Financial Inclusion and Financial Literacy | | TRAI | Telecom Regulatory Authority of India | | TSP | Technology Service Provider | | UCB | Urban Co-operative Bank | | UKFSA | UK Financial Services Authority | | USOF | Universal Service Obligation Fund | | UT | Union Territory | | ZIP | Zone Improvement Plan |

Summary of Recommendations 1 Given the enormity of the tasks and complexity of the issues, the Committee believes that dovetailing relevant financial policies with necessary structural reforms where the government has a central role can deliver real financial inclusion in a sustainable and stable manner [Recommendation 1.1]. The Committee felt that although a quantum jump in banking access has taken place, a significant element of regional exclusion persists for various reasons that need to be addressed by stepping up the inclusion drive in the north-eastern, eastern and central states to achieve near-universal access. This may entail a change in the banks’ traditional business model through greater reliance on mobile technology for ‘last mile’ service delivery, given the challenges of topography and security issues in some areas. The Government has an important role to play in ensuring mobile connectivity. In some of the areas, mobile connectivity may not be commercially viable to start with, but the telecom service providers may be encouraged to use their corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds for this purpose. The Commit-tee is of the view that the State-Level Bankers Committee (SLBC) is an appropriate forum to address such infrastructure issues in a collaborative manner. The use of Universal Service Obligation Fund (USOF), a non-lapsable fund designed to support a variety of innovation initiatives, can also be explored in this regard. [Recommendation 1.2]. Considering the still significant exclusion of women, the Committee recommends that banks have to make special efforts to step up account opening for females. Given the government’s emphasis on the welfare of the girl child, the Committee suggests that the government can consider a welfare scheme—Sukanya Shiksha —that can be jointly funded by the central and state governments. The scheme will link education with banking habits by crediting a nominal amount, in the name of each girl child belonging to the lower income group who enrols in middle school. This would make it incumbent on the school and the lead bank and its designated branch to open a bank account for social cash transfer. This scheme can also have the benefit of lowering school dropout rates and empower the girl child [Recommendation 1.3]. Given the predominance of individual account holdings, the Committee recommends that a unique biometric identifier such as Aadhaar should be linked to each individual credit account and the information shared with credit information companies. This will not only be useful in identifying multiple accounts, but will also help in mitigating the overall indebtedness of individuals who are often lured into multiple borrowings without being aware of its consequences [Recommendation 1.4]. The Committee recommends that a low-cost solution based on mobile technology can be a good candidate for improving financial inclusion by enhancing the effectiveness of ‘last mile’ service delivery [Recommendation 1.5]. The Committee recommends that a key component of the financial inclusion policy should be to improve the credit system for the underprivileged, particularly millions of poor agricultural households, so as to ensure a perceptible shift of credit demand from the informal to the formal sector [Recommendation 1.6].

__________________________________________________________ 2. The Committee observes that despite improved financial access, usage remains low, underscoring the need to better leverage technology to facilitate usage [Recommendation 2.1]. On the basis of cross-country evidence and our own experience, the Committee is of the view that to translate financial access into enhanced convenience and usage, there is a need for better utilisation of the mobile banking facility and the maximum possible G2P payments, which would necessitate greater engagement by the government in the financial inclusion drive [Recommendation 2.2].

__________________________________________________________ 3. The Committee recommends that in order to increase formal credit supply to all agrarian segments, the digitisation of land records should be taken up by the states on a priority basis [Recommendation 3.1]. In order to ensure actual credit supply to the agricultural sector, the Committee recommends the introduction of Aadhaar-linked mechanism for Credit Eligibility Certificates. For example, in Andhra Pradesh, the revenue authorities issue Credit Eligibility Certificates to Tenant Farmers (under ‘Andhra Pradesh Land Licensed Cultivators Act No 18 of 2011'). Such tenancy /lease certificates, while protecting the owner’s rights, would enable land-less cultivators to obtain loans. The Reserve Bank may accordingly modify its regulatory guidelines to banks to directly lend to tenants / lessees against such credit eligibility certificates [Recommendation 3.2]. The Committee recommends phasing out the interest subvention scheme and ploughing the subsidy amount into a universal crop insurance scheme for small and marginal farmers (detailed in Chapter 8) [Recommendation 3.3]. The Committee recommends that the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) should continue to have a built in consumption credit component, recognising that while agricultural income could be lumpy, expenditure is an on-going process that results in negative cash flow for several months. A scheme of ‘Gold KCC’ with higher flexibility can be introduced for borrowers with prompt repayment records. Expenditure towards organic certification should be allowed under KCC. The government-sponsored personal insurance may be dovetailed with the KCC scheme. Going forward, a KCC can be explored which can provide a benefits tracking mechanism [Recommendation 3.4]. The Committee is of the view that with the digitisation of land records, which secures ownership, co-operative farming should be encouraged at the local level by panchayats. This would enhance the use of mechanisation and reduce input costs and prices. NGOs and Farmer Associations should educate farmers on the benefits of land consolidation. In each district, the efforts of the supply co-operatives, marketing co-operatives and credit co-operatives should be strengthened to encourage co-operative farming [Recommendation 3.5]. The Committee is of the view that the best way to take JLGs forward would be to have them join hands and form Producer Organisations. Capacity building of JLG members should be made essential and ways should be devised for market linkage of the produce/products [Recommendation 3.6]. The Committee recommends that a universal crop insurance scheme covering all crops should be introduced starting with small and marginal farmers with a monetary ceiling say of ₹200,000. The insurance should be mandatory for all agricultural loans. The insurance should be made affordable, with the farmer paying a nominal premium and the balance coming from government subsidy. The government can phase out the agricultural loan interest subvention scheme and plough back that allocation into the crop insurance subsidy. A graded crop insurance could be made available to medium and large cultivators with higher monetary ceiling and lower government subsidy [Recommendation 3.7]. The government may restructure the Agriculture Insurance Company (AIC) to take up the role of a dedicated ‘Crop Insurance Corporation’. It should develop/run the programmes, promote competition including inviting bids from private insurance companies, usher in state-of-the art technology at all levels and arrange reinsurance of claims as well as the intensification of Automated Weather Stations (AWS) to ensure that at least one accredited AWS is set up every 10 kilometres. There would also be a need for installing additional rainfall data loggers [Recommendation 3.8]. The Committee feels that the use of technology would make the insurance scheme more efficient. Satellite imagery can be used for ‘crop mapping’ and to assess damage. GPS-enabled hand-held devices can be used for ‘ground trothing’. In addition, drones and dove, micro satellites could also be deployed to assess crop damages. This will reduce the number of crop-cutting experiments required and will ensure faster claims settlement [Recommendation 3.9].

__________________________________________________________ 4. The Committee recommends that any policy action for the MSME sector would need to consider several possibilities, be it new institutions or intermediaries who can help bridge the information gaps that plague these entities or even innovative ways of providing finance to this sector [Recommendation 4.1]. Keeping in view the extant over-extension of guarantees by the CGTMSE as well as the international evidence, the Committee recommends that multiple guarantee agencies, both public and private, that can provide credit guarantees in niche areas may be encouraged. This will not only reduce the burden on the CGTMSE but also make the extant insurance scheme economically viable [Recommendation 4.2]. In order to deepen the credit guarantee market, the role of counter guarantee and re-insurance companies should be explored [Recommendation 4.3]. MSEs that can provide collateral should not be put under the guarantee scheme, thereby reducing the pressure on the CGTMSE [Recommendation 4.4]. Accordingly, the Committee recommends a system of unique identification for all MSME borrowers and the sharing of such information with credit bureaus. While such identification and tracking is not an issue with registered MSMEs where the CIN/UAN can be used alongside their PAN number, biometric Aadhaar identification should form the basis for proprietary and partnership concerns. Even in the case of registered MSMEs, it will be useful to collect and link the Aadhaar identification of directors so as to check possible fraudulent operation by the same set of persons [Recommendation 4.5]. The Committee recommends exploring a system of professional credit intermediaries/ advisors for MSMEs, which could help bridge the information gap and thereby help banks to make better credit decisions. The credit intermediaries/ advisors could function in a transparent manner for a fee and be regulated by the Reserve Bank [Recommendation 4.6]. Besides exploring innovative financing methods, the Committee recommends that a framework for movable collateral registry for MSEs may be examined to step up financing to this sector [Recommendation 4.7].

__________________________________________________________ 5. The Committee recommends that commercial banks in India may be enabled to open specialised interest-free windows with simple products like demand deposits, agency and participation securities on their liability side and to offer products based on cost-plus financing and deferred payment, deferred delivery contracts on the asset side [Recommendation 5.1]. In the event that interest-free banking is allowed in India, the extant regulatory guidelines in respect of capital and liquidity as applicable in the case of commercial banks would have to be made applicable to those as well [Recommendation 5.2].

__________________________________________________________ 6. Multiple models and partnerships covering different niches should be encouraged. This is particularly the case among national full-service banks, regional banks of various types, NBFCs and semi-formal financial institutions, as well as the newly-licensed payments banks and small finance banks [Recommendation 6.1]. The Committee recommends that BCs should increasingly be established at fixed location BC outlets: the BC outlet/Customer Service Point (CSP) could be opened in the Village Panchayat Office, kirana shop, personal residence or any other convenient location that could win the confidence of the customer [Recommendation 6.2]. Monitoring of BCs should be allotted to designated link branches in the area. This will help strengthen BC operations and bridge the trust deficit [Recommendation 6.3]. The competence of BCs should not be taken for granted. Accordingly, the Committee recommends a graded system of certification of BCs, from basic to advanced training. BCs with a good track record and advanced training can be trusted with more complex financial tasks such as credit products that go beyond deposit and remittance. The BC model increasingly needs to move from cost to revenue generation to make it viable [Recommendation 6.4]. The Committee recommends that banks will have to consider introducing a cash management system that can help to scale up BC operations [Recommendation 6.5]. The Committee recommends that the Indian Banks’Association (IBA) may create a Registry of BC Agents wherein BCs will have to register before commencement of operations. The registration process should be simple online process with photo and Aadhaar identification. It could include other details such as name of the BC, type of BC, location GIS coordinates of fixed point BCs, nature of operations, area of operation and, at a subsequent stage, their performance record including delinquency. This database can be made dynamic with quarterly updates, including a list of black-listed BCs which no other bank should approach or work with. This would help banks and other agencies to track the movement of BCs and supervise their operations more efficiently [Recommendation 6.6]. The Committee recommends that the Reserve Bank should take the lead in creating a geographical information system (GIS) to map all banking access points which would help improve the efficiency of regulating, supervising and monitoring of banking operations. Over time, a harmonised database of financial inclusion footprints, in terms of outlets, service points, devices and agent networks, may be put in place using a GIS platform [Recommendation 6.7]. The Committee is of the view that it is imperative for banks to conduct periodic reviews of its efforts under their financial inclusion plans (FIPs) at the Board level. This would facilitate banks to take timely corrective steps and prepare concrete strategic action plans [Recommendation 6.8]. The Committee recommends that NABARD may work out a programme along with other stakeholders to step up the SBLP, particularly in regions with less penetration. In this context, the District Consultative Committee (DCC) and SLBCs are the appropriate forum to sort out inter-institutional issues and set monitorable and implementable targets (see Chapter 10) [Recommendation 6.9]. The Committee is of the view that training of BC should also include their sensitisation towards SHGs [Recommendation 6.10]. Keeping in view the indebtedness and rising delinquency, the Committee is of the view that the credit history of all SHG members would need to be created, linking it to individual Aadhaar numbers. This will ensure credit discipline and will also provide comfort to banks [Recommendation 6.11]. The Committee sees the SHG-corporate linkage working as ‘micro-factories’ of corporates. An example is ITC’s‘Mission Sunehra Kal’. Corporates can be encouraged to nurture SHGs as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives [Recommendation 6.12]. The Committee recommends that bank credit to MFIs should be encouraged. The MFIs must provide credit information on their borrowers to credit bureaus through Aadhaar-linked unique identification of individual borrowers [Recommendation 6.13]. The Committee thinks it important to ensure adequate funding from channels that have stronger access (e.g., banks) to channels that are equipped and have the appetite to extend small-ticket loans, but may not have the same access to funding (e.g., NBFCs). The suitability of the products for the customer needs to be kept in view in this regard. Encouraging the development of the securitisation market for such small-ticket loans could be useful in this respect and help commercial banks acquire loans that qualify for priority sector lending [Recommendation 6.14]. The Committee is of the view that in order to preserve institutional neutrality, credit reporting requirements need to be harmonised across all credit providers. For instance, all lenders to the small borrower segment must be mandated to report to credit bureaus as has been the case with NBFC-MFIs. Therefore, the picture of indebtedness of the borrower must also include outstanding KCC, GCC and SHG loans. Once a realistic picture of the total indebtedness of the borrowers has been obtained, restrictions such as the maximum number of lenders per borrower can be removed, paving the way for competition to push down interest costs for the small borrower [Recommendation 6.15]. CICs also have a significant role to play in enabling credit flow to MSMEs, especially those without formal registration and standard accounting practices by helping them build a sound credit history (Chapter 5 provides details) [Recommendation 6.16]. In the absence of a framework for sharing of information among CICs, the same credit information is required to be provided to all CICs, which not only leads to avoidable duplication but also magnifies the reporting burden. The Committee recommends that a mechanism for mutual sharing of basic credit information for a fee among CICs should be mandated so that the lender could report to any of the CICs [Recommendation 6.17]. The advent of Payment Banks, an increasing number of cash-in and cash-out points through BCs, micro ATMs, mobile wallets and Rupay in the rural areas will enable customers to increase their access to the formal payment system. Over time, this would make it easier for banks to assess customers’ repayment capability, as most of the cash flows will become digitally recorded. This, in turn, will lead to lenders being able to conceive and build automated credit decision models, which reduces the cost of credit underwriting. This would also enable banks to better monitor cash flows on an ongoing basis and to step up risk mitigating measures [Recommendation 6.18]. The Committee is of the view that the tax-exempt status for securitisation vehicles needs to be restored so that such entities do not have to pay distribution tax, given their critical role in efficient risk transmission. This will not lead to a loss of tax revenues since the income will still be fully traceable and taxable in the hands of the investors. Besides reviving and strengthening the securitisation market, these vehicles will allow a wide range of investors to participate in financing the pool of assets by means of Special Purpose Vehicles and rated Pass-through Certificates (PTCs). These would need to be structured such that the originator has continued incentives to monitor the project while having reduced their own exposure to the full extent of the project risk. This instrument can facilitate the growth of the retail credit market, particularly in areas such as home loans, farm loans and loans to landless labourers [Recommendation 6.19]. The current restriction requiring that the all-inclusive interest charged to the ultimate borrower by the originating entity must not exceed the base rate of the purchasing bank plus 8 per cent per annum must be removed, because this dissuades originators from expanding to low-access regions and sectors due to the high operating and borrowing costs [Recommendation 6.20].

__________________________________________________________ 7 The Committee is of the view that given the low penetration of ATMs, installing more ATMs in rural and semi-urban centres will create more touch points for customers. The Financial Inclusion Fund (FIF) may be utilised to encourage rural ATM penetration [Recommendation 7.1]. The Committee recommends that interoperability of micro ATMs should be allowed to facilitate the usage of cards by customers in semi-urban and rural areas across any bank micro ATM and BC. For this, connectivity of micro ATMs to the National Financial Switch should be enabled. Adequate checks and balances should be put in place to ensure customer protection and system safeguards [Recommendation 7.2]. Considering the widespread availability of mobile phones across the country, the Committee recommends the use of application-based mobiles as PoS for creating necessary infrastructure to support the large number of new accounts and cards issued under the PMJDY. Initially, the FIF can be used to subsidise the associated costs. This will also help to address the issue of low availability of PoSs compared to the number of merchant outlets in the country. Banks should encourage merchants across geographies to adopt such application-based mobile as a PoS through some focused education and PoS deployment drives [Recommendation 7.3]. The Committee feels that banks need to introduce a simple registration process for customers to seed their mobile number for alerts as well as financial services. The Reserve Bank has already required banks to enable an interoperable ATM channel for mobile number registration [Recommendation 7.4]. The Committee recommends that the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) should ensure faster development of a multi-lingual mobile application for customers who use non-smart phones, especially for users of NUUP; this will address the issue of linguistic diversity and thereby promote its popularisation and quick adoption [Recommendation 7.5]. The Committee is of the opinion that the government may undertake initiatives to resolve the issues of number of steps per session in a transaction on NUUP, session drops and session charges; the Reserve Bank and NPCI may co-ordinate with the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) on this matter. Aadhaar and e-KYC should be the uniform KYC accepted by all regulators including TRAI [Recommendation 7.6]. For smart phone users, the Committee recommends that the NPCI work on developing a standardised interface application, which will ensure interoperability in mobile-banking transactions for customers. It should be implemented with proper due diligence and the required security checks [Recommendation 7.7]. The Committee recommends that pre-paid payment instrument (PPI) interoperability may be allowed for non-banks to facilitate ease of access to customers and promote wider spread of PPIs across the country. It should however require non-bank PPI operators to enhance their customer grievance redressal mechanism to deal with any issues thereof [Recommendation 7.8]. The Committee is of the view that for non-bank PPIs, a small-value cash-out may be permitted to incentivise usage with the necessary safeguards including adequate KYC and velocity checks [Recommendation 7.9]. Currently, many merchants discriminate against card payment by levying a surcharge on credit card transactions, which should not be allowed once the merchant has voluntarily agreed to participate in such modes of payments [Recommendation 7.10]. As there is a gap not only between product availability and awareness about such products but also about the precautions to be followed while using a digital or electronic payment product, the Committee recommends a wider financial literacy drive that exploits all possible communication channels to educate customers. The financial support for such campaigns can be drawn from the FIF [Recommendation 7.11].

__________________________________________________________ 8. The Committee recommends that the deposit accounts of beneficiaries of government social payments, preferably all deposits accounts across banks, including the ‘in-principle’ licensed payments banks and small finance banks, be seeded with Aadhaar in a time-bound manner so as to create the necessary eco-system for cash transfer. This could be complemented with the necessary changes in the business correspondent (BC) system (see Chapter 6 for details) and increased adoption of mobile wallets to bridge the ‘last mile’ of service delivery in a cost-efficient manner at the convenience of the common person. This would also result in significant cost reductions for the government besides promoting financial inclusion [Recommendation 8.1]. Given the increased role of the states in public welfare and the elimination of poverty and the higher transfer payments by the state governments following the 14th Finance Commission recommendations, the Committee recommends that the states need to adopt direct benefit transfer (DBT) more vigorously. In this context, the State-Level Bankers Committee (SLBC) can play an active role in addressing issues relating to convenient banking access, Aadhaar linking of beneficiary accounts and related infrastructure challenges [Recommendation 8.2]. The Committee recommends that the government may phase out the agricultural input subsidy and replace it with an income transfer scheme, which could potentially transform the agriculture sector besides promoting financial inclusion. This would first require digitisation of land records for clear titles and credit linkage to establish evidence of cultivation [Recommendation 8.3].

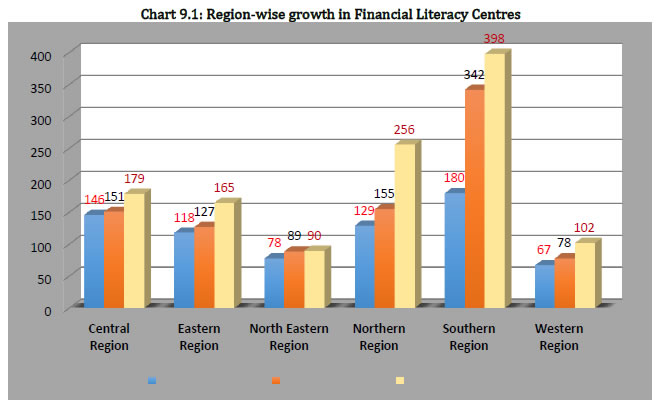

__________________________________________________________ 9. The FLC network needs to be strengthened to deliver basic financial literacy at the ground level. Banks need to identify a few lead literacy officers who could train the people manning FLCs. The lead literacy officer in turn could be trained by the Reserve Bank in its College of Agricultural Banking (CAB) for which simple course material can be developed by CAB in collaboration with the concerned department in the Reserve Bank, i.e., the FIDD. Since simplicity in communicating complex financial issues is important, CAB can associate creative communication experts in the design of key messages, exploiting innovative technologies and relevant content based on customer segments [Recommendation 9.1]. A ‘one size fits all’ approach for financial education might be less than ideal as different target groups need different kinds of financial education. As a result, the content needs to be customised for different target groups. These will need to be followed up at periodic intervals to ascertain its impact [Recommendation 9.2]. There is a need for a structured programme for holding periodic financial literacy camps in pre-identified areas in every district, which should be regularly monitored by the DCCs. The lead bank for the district should play a leading role in identifying and allocating areas among the participating banks [Recommendation 9.3]. Local resources such as NGOs and theatre groups can be tapped to spread the message of literacy in an interesting manner to the local population for which funding can come from financial inclusion fund [Recommendation 9.4]. A technology-driven system through interactive screens/kiosks to encourage self-learning by people newly inducted into the financial system can be explored. The content can be updated from a central location, using the existing software. Possible locations for such kiosks, such as post offices, community health centres and panchayat offices, can be explored [Recommendation 9.5]. A financial literacy week can be observed every year in which participants demonstrate and exhibit the financial literacy tools and techniques that they use and share their success stories. This will bring out best practices in the system to achieve large-scale financial literacy. This will serve as a platform for co-ordination among different stakeholders of financial literacy [Recommendation 9.6]. Rural Self Employment Training Institutes (RSETIs), which have a dedicated infrastructure in each district of the country to impart training and skill upgrading of rural youth, can also be used for financial education of MSMEs [Recommendation 9.7]. The Committee recommends that the Reserve Bank commission periodic dipstick surveys across states to ascertain the extent of financial literacy and identify gaps in this regard. The results can provide policy-makers with a better understanding of the demand-side challenges [Recommendation 9.8]. The first pillar of complaint and grievance redressal is the branch, failing which it is the bank’s internal ombudsman. Each branch should, therefore, be required to prominently display the name, phone number and email address of the designated officials for such complaints. The Reserve Bank should ensure compliance through random branch visits [Recommendation 9.9]. The Reserve Bank Banking Ombudsman at regional offices may make periodic field visits to directly receive customer complaints [Recommendation 9.10]. While continuing with the existing mechanism, all regulated entities would be required to put in place a technology-based platform for SMS acknowledgement and disposal of customer complaints, which can provide an audit trail of grievance redressal. All banks must have an online portal for customers to fill complaints [Recommendation 9.11]. Banks may be required to submit the consolidated status of number of complaints received and disposed off under broad heads to the CEPD, and the Reserve Bank, in turn, can release an annual bank-wise status in the public domain [Recommendation 9.12]. The Banking Codes and Standards Board of India (BCSBI) in collaboration with the Banking Ombudsman and the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA) can explore the possibility of devising a scheme based on transparent criteria that incentivises banks to expeditiously address customer grievances [Recommendation 9.13].

__________________________________________________________ 10. The Information Monitoring System needs to be strengthened. Currently, data flow takes a bottom-up approach wherein the branches of the banks in a district submit data to the lead bank and the lead bank consolidates the data manually and prepares the district-level database for review in meetings. Further, all lead banks submit data to the SLBC, which consolidates the state-level data for review in SLBC meetings. The Committee believes that it is equally important to explore a top-down approach for data flow, in a simple, uniform and meaningful format, with the help of the Core Banking Solution of the regional offices of the concerned bank. The monitoring process needs to be standardised in terms of reports, and also cover usage parameters. The data can flow from the central database of banks to various lower levels to ensure data consistency and integrity [Recommendation 10.1]. District credit plans need to be more realistic. The district-level credit plans should be prepared by lead banks, taking into account the potential linked plans prepared by NABARD every year which should take into account the availability of infrastructure, marketing facilities and policies/ programmes of the government, including the support by the concerned government departments of the local level in the spirit of the lead bank scheme [Recommendation 10.2]. At present, public sector banks have been given the lead bank responsibility with the exception of one private bank. The Committee feels that the responsibility of the SLBC / lead bank scheme should be given to different banks on a rotation basis for a fixed time-frame (of say 3 years) to facilitate fresh thinking and initiative as well as to instil a spirit of competition [Recommendation 10.3]. The Committee is of the view that banks with lead bank responsibilities can create a separate webpage with respect to their lead bank operations including the conduct of business in DCC meetings [Recommendation 10.4]. The current policy discussions across most SLBCs put substantial emphasis on the credit-deposit (CD) ratio. Rather, greater focus should be on development aspects for which the CD ratio could be a by-product. Such deliberations can include livelihood models, social cash transfer issues, gender inclusion, inclusion of different groups, Aadhaar seeding and universal account opening. There can also be other sets of issues that are region-specific and can focus on areas such as policy towards fraudulent deposit/ investment schemes, physical/network infrastructure and recovery management [Recommendation 10.5]. Given the focus on technology and the increasing number of customer complaints relating to debit/credit cards, the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) may be invited to SLBC meetings. They may particularly take up issues of Aadhaar-linkage in bank and payment accounts [Recommendation 10.6].

Chapter 1 : Financial Inclusion in India Access counts, but usage matters Reforming to transform is a marathon, not a sprint.

Clearly, our financial inclusion reform has been transformational. Extracts from the Hon’ble Prime Minister’s Address at Delhi Economics Conclave, 6 November 2015 Financial inclusion, broadly understood as access to the formal financial sector for the mar-ginalised and formal-finance deprived sections of society, has increasingly come to the fore-front of public discourse in recent years. Policymakers all over the world are exploring ways and means to ensure greater inclusion of the financially excluded segments of society. There has been renewed global impetus to financial inclusion, particularly following the global financial crisis in 2008. It is believed that financial inclusion could be welfare-enhancing and, as a result, there is greater political support for the entire process. In India, providing access to formal financial services and products has been a thrust of banking policy for several decades. The current thinking at the global level has also had its echo in India, with policymakers at various levels undertaking a wide range of measures to include the excluded or the under-served within the fold of formal finance. Accordingly, the Government and the Reserve Bank have undertaken a whole host of innovative and dedicated measures to drive forward the financial inclusion agenda. Against this backdrop, the Committee felt that it would be useful to take stock of the current status of financial inclusion so as to better understand the kind of policy interventions that could accelerate the process. Accordingly, in what follows, the extant evidence is carefully analysed, focusing first on physical indicators such as branch network and accounts and, subsequently, on financial indicators such as credit and deposits. The international experience is dwelt upon, as appropriate and relevant. In order to keep the discussion contextual, the focus is on the more recent period, i.e., the period from 2006 onwards, because several previous Committees have already extensively documented India’s financial inclusion experience within a broader historical context (see Annex for a summary). The big push towards financial inclusion in India has emanated from the Pradhan Mantri JanDhan Yojana (PMJDY) in August 2014 and the Jan Dhan Aadhaar Mobile (JAM) trinity articulated in the Government’s Economic Survey 2014-15 as well as the special thrust on financial inclusion by the Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC) that includes a Technical Group for dedicated attention to this issue. Thus, the inclusion drive has gone beyond the confines of various financial regulators and assumed the character of a broader national development policy goal. Recommendation 1.1

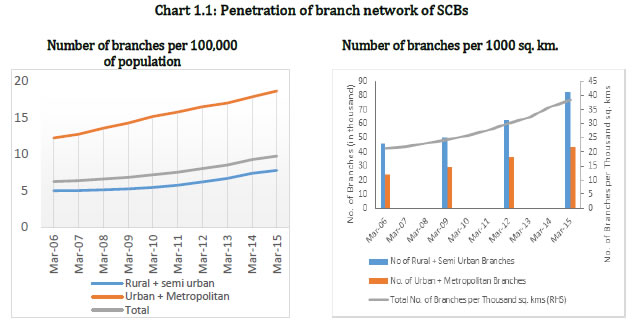

Given the enormity of the tasks and complexity of the issues, the Committee believes that dovetailing relevant financial policies with necessary structural reforms where the government has a central role can deliver real financial inclusion in a sustainable and stable manner. Banking penetration of rural and semi-urban areas has increased significantly At the turn of the century, the expansion of brick-and-mortar branches, despite several efforts, was limited. The low penetration of formal banking led the Reserve Bank to look at financial inclusion as a major policy drive. The slew of measures that followed were the introduction of Business Facilitators (BFs) and Business Correspondents (BCs) and deregulation of the opening of ATMs and branches, while ensuring sufficient coverage to hitherto unbanked areas. Concurrently, relaxations in the BC model were made to bridge the ‘last mile’ problem. This accelerated the pace of branch opening, with more branches being opened in rural and semi-urban areas. Notwithstanding this development, the number of branches per 100,000 of population in rural and semi-urban areas is still less than half of that in urban and metropolitan areas (Chart 1.1 and Table 1.1). | Table 1.1: Branch Expansion of SCBs | | As on March | Number of

Branches | Estimated population*

(in million) | Branches/

100,000 population | | Rural + Semi-urban | Urban + Metro-politan | Total | Rural + Semi-urban | Urban + Metro-politan | Total | Rural + Semi-urban | Urban + Metro-politan | Total | | 2001 | 44,905 | 20,713 | 65,618 | 851 | 177 | 1,028 | 5.3 | 11.7 | 6.4 | | 2006 | 45,673 | 23,904 | 69,577 | 920 | 195 | 1,115 | 5.0 | 12.3 | 6.2 | | 2010 | 53,086 | 31,072 | 85,158 | 980 | 211 | 1,191 | 5.4 | 15.2 | 7.2 | | 2014 | 76,753 | 40,958 | 1,17,711 | 1,044 | 228 | 1,272 | 7.3 | 17.9 | 9.2 | | 2015 | 82,358 | 43,716 | 1,26,074 | 1,061 | 233 | 1,294 | 7.8 | 18.7 | 9.7 | | June 2015 | 82,794 | 43,910 | 1,26,704 | 1,065 | 235 | 1,300 | 7.8 | 18.7 | 9.7 | | *Population estimates are based on CAGR between Census 2001 and Census 2011 data |

Concurrent with higher branch expansion in semi-urban and rural areas, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for both the number of individual saving bank deposit accounts as well as deposit amounts outstanding therein was the highest for semi-urban regions followed by rural, urban and metropolitan regions (Table 1.2). | Table 1.2: Growth in Individuals’ Savings Bank Deposits Accounts with SCBs | | Population Group | Number of Individual Saving Bank Deposits Accounts

(million) | Individual Saving Bank Deposits’ Amount Outstanding

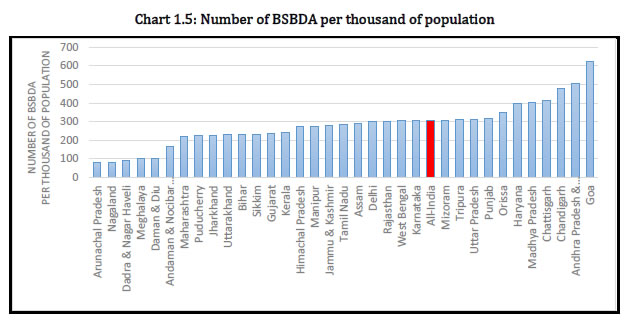

(₹. billion) | | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | CAGR (%) | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | CAGR (%) | | Rural | 104 | 167 | 384 | 15.6 | 962 | 1,703 | 3,601 | 15.8 | | Semi-urban | 85 | 136 | 320 | 15.9 | 1,124 | 2,155 | 4,470 | 16.6 | | Urban | 68 | 97 | 186 | 11.8 | 1,246 | 2,381 | 4,541 | 15.5 | | Metropolitan | 71 | 100 | 180 | 10.9 | 1,838 | 3,731 | 6,476 | 15.0 | | All India | 329 | 500 | 1,070 | 14.0 | 5,170 | 9,970 | 19,088 | 15.6 | | CAGR is for all scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) including regional rural banks (RRBs) during 2006-15. | In normal conditions, the availability of banking services could be predicated on the level of economic activity. The Committee examined whether the recent supply-push towards financial inclusion has made a difference. Regression analysis suggests that while per capita income is the dominant factor in explaining the penetration of banking services, the slope of the regression line has flattened over time, suggesting policy-induced improvements in supply in recent times (Chart 1.2). Apart from the regulatory thrust on branch expansion, in order to provide basic banking services to the marginalised sections of society, banks were advised to open ‘no-frills’ accounts, which were subsequently labelled as Basic Saving Bank Deposit Accounts (BSBDA). In the past five and a half years, these BSBD accounts have risen more than six-fold and nearly half of these accounts were opened through Business Correspondents (BCs) (Chart1.3). However, eastern, north-eastern and central regions lag behind in terms of banking penetration The relative position of various states/union territories in terms of bank branch coverage, normalised by population (demographic bank penetration) and area (geographic branch penetration), respectively, are given in Chart 1.41. While geographic penetration can be interpreted as a proxy for the average distance of a potential customer from the nearest physical bank outlet, higher demographic penetration would imply easier access. While demographic penetration has increased one-and-a-half times during 2006-15, the north-eastern states as also states such as Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh are less penetrated in terms of the number of branches in relation to their population. Even the state-wise numbers for BSBD account density as on March 2015 suggest that several north-eastern and eastern states lag behind (Chart 1.5).  Recommendation 1.2

The Committee felt that although a quantum jump in banking access has taken place, a significant element of regional exclusion persists for various reasons that need to be addressed by stepping up the inclusion drive in the north-eastern, eastern and central states to achieve near-universal access. This may entail a change in the banks’ traditional business model through greater reliance on mobile technology for ‘last mile’ service delivery, given the challenges of topography and security issues in some areas. The Government has an important role to play in ensuring mobile connectivity. In some of the areas, mobile connectivity may not be commercially viable to start with, but the telecom service providers may be encouraged to use their corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds for this purpose. The Committee is of the view that the State-Level Bankers Committee (SLBC) is an appropriate forum to address such infrastructure issues in a collaborative manner. The use of Universal Service Obligation Fund (USOF), a non-lapsable fund designed to support a variety of innovation initiatives, can also be explored in this regard. Notwithstanding substantial improvements, gender inclusion remains a concern Over time (2006-15), considerable improvements in terms of account density, i.e., the number of account per thousand of population, have been achieved. Although the account density for females has more than tripled, these numbers are far lower than the account density of males (Tables 1.3). | Table 1.3: Individual Savings Bank Account of SCBs – Female Population | | | Total female population | Rural female population | Total female population | | Number of female's savings bank accounts per thousand of female population | Amount outstanding per female’s savings bank account

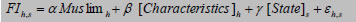

(in thousand) | | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | | Minimum among states/ UTs | 49 | 60 | 277 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 6 | | Maximum among states/ UTs | 712 | 893 | 1577 | 25 | 31 | 43 | 31 | 45 | 60 | | Median of States/ UTs | 146 | 189 | 588 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 14 | 18 | 16 | | All India | 143 | 196 | 536 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 17 | 15 | The higher the share of rural and women population, the lower the financial inclusion The various indicators of financial inclusion point toward differences in the level of financial inclusion across the population group as well as gender. It was found that states having a relatively higher share of rural population and a higher share of female population generally have a comparatively lower level of financial inclusion (Box 1.1). Box 1.1: The effects of women and rural population on financial inclusion It is generally known that rural areas and women typically encounter greater constraints in becoming financially included. To examine this empirically, the various indicators of financial inclusion are regressed on the share of rural population (Share_Rural) and the share of female population (Share_Female), respectively, after taking into account state-level controls, such as per capita income and literacy rates. The specification for state i is expressed as follows: The results suggest that states with a larger proportion of females and those with a larger share of rural populace exhibit significantly lower levels of financial inclusion. | Table: Financial inclusion and various characteristics | | Variable | Deposit accounts per 1000 of population | Credit accounts per 1000 of population | Per capita credit | Per capita deposit | | Share_rural | -0.18***

(0.05) | | -0.10

(0.08) | | -0.54***

(0.04) | | -0.14***

(0.03) | | | Share_female | | -0.15

(2.40) | | 5.89

(4.38) | | -10.9***

(3.03) | | -5.13***

(0.81) | | Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | | N.Obs; R-sq. | 32, 0.76 | 32; 0.73 | 32; 0.49 | 32; 0.54 | 32; 0.77 | 32; 0.68 | 32; 0.40 | 32; 0.52 | Controls include per capita NSDP and literacy rate, both expressed in logarithmic form.

Standard errors in parentheses

***, ** and * denote statistical significant at 1, 5 and 10%, respectively. | Recommendation 1.3

Considering the still significant exclusion of women, the Committee recommends that banks have to make special efforts to step up account opening for females. Given the government’s emphasis on the welfare of the girl child, the Committee suggests that the government can consider a welfare scheme—Sukanya Shiksha —that can be jointly funded by the central and state governments. The scheme will link education with banking habits by crediting a nominal amount, in the name of each girl child belonging to the lower income group who enrols in middle school. This would make it incumbent on the school and the lead bank and its designated branch to open a bank account for social cash transfer. This scheme can also have the benefit of lowering school dropout rates and empower the girl child. Not only deposit account penetration, but also commercial bank credit accounts and amount outstanding has improved, especially in rural and semi-urban areas During 2006-2015, while the number of credit accounts of SCBs increased at a CAGR of 6.0 per cent, the rate of growth was higher for rural and semi-urban areas. Even credit growth was more evenly distributed around the mean, with a particular tilt towards rural and semi-urban areas (Table 1.4). | Table 1.4: Credit Growth of Scheduled Commercial Banks | | | Credit accounts (million) | Credit outstanding (₹ billion) | | Population Group | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | CAGR (%) | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | CAGR (%) | | Rural | 29 | 36 | 50 | 6.4 | 1,261 | 2,493 | 5,982 | 18.9 | | Semi-urban | 21 | 27 | 41 | 7.4 | 1,514 | 3,200 | 7,600 | 19.6 | | Urban | 13 | 16 | 21 | 5.8 | 2,458 | 5,585 | 11,039 | 18.2 | | Metropolitan | 23 | 40 | 33 | 4.1 | 9,905 | 22,174 | 44,170 | 18.1 | | All India | 86 | 119 | 145 | 6.0 | 15,138 | 33,452 | 68,791 | 18.3 | | CAGR is for all scheduled commercial banks (SCBs), including Regional Rural Banks (RRBs), during 2006-15 | Individual and small accounts dominate commercial banks’ credit portfolio in terms of numbers, making it amenable to biometric Aadhaar linkage to manage credit risk, sniff out multiple lending and curtail over-indebtedness. At the all-India level, the share of individuals in the total number of credit accounts was 94 per cent in 2015 and the amount outstanding was about one-third of total credit. Small-size loans (i.e., up to ₹1 million) contributed to over 96 per cent of the total number of loan accounts. Occupation-wise, agriculture and personal loans together constitute about 85 per cent of the loan accounts and nearly 30 per cent loan amounts outstanding. Small and marginal farmers account for over 35 per cent of agriculture credit. Small agriculture loans up to ₹ 0.2 million accounted for over 42 per cent of agriculture credit. The information2 on the Incidence of Indebtedness (IOI), i.e., the percentage of households that had taken cash loans, was 31 per cent in rural areas with their debt-to-asset ratio (DAR) reflecting repayment capacity at 3.2 per cent. In contrast, for rural-cultivators in Andhra Pradesh the IOI was as high as 70 per cent with the DAR at 14.3 per cent. The Committee felt that better information and analysis of indebtedness could have helped mitigate the credit crisis in Andhra Pradesh. Recommendation 1.4

Given the predominance of individual account holdings, the Committee recommends that a unique biometric identifier such as Aadhaar should be linked to each individual credit account and the information shared with credit information companies. This will not only be useful in identifying multiple accounts, but will also help in mitigating the overall indebtedness of individuals who are often lured into multiple borrowings without being aware of its consequences. Rapid increase in mobile penetration alongside Aadhaar makes it the ideal tool for low-cost financial service delivery for realising the government’s JAM Vision As per the latest Census of House Listing and Housing Survey data 2011, the proportion of households availing of banking services has increased to 59 per cent in 2011 from 35 per cent in 2001. It also indicates that 59 per cent of households possess mobile phones. Subsequently, mobile penetration, Aadhaar coverage and BSBD accounts have accelerated sharply (Chart 1.6)3. Empirical evidence suggests that basic banking services could be delivered at low cost through mobile technology and the security of transactions could be enhanced through biometric identification. Recommendation 1.5

The Committee recommends that a low-cost solution based on mobile technology can be a good candidate for improving financial inclusion by enhancing the effectiveness of ‘last mile’ service delivery. At the current juncture of economic development, the bulk of rural households have low income, making their credit needs paramount, which is met to a large extent by the informal sector despite significant improvement in banking. A litmus test for financial inclusion would be to ensure that an increasing share of the credit demand of this segment is met by the formal credit sector. A primary requirement for opening a bank account is that people should have sufficient income to save after meeting consumption needs. The Socio-economic Caste Census 2011 reveals that more than half of the rural households depend on manual casual labour and another 30 per cent depend on cultivation for their livelihood. The main income-earning member of around three-fourth of rural households earns less than ₹ 5,000 per month. Only 8 per cent of rural households earn more than ₹ 10,000 per month. Of 138 million agriculture landholders, 67 per cent are marginal farmers (having land size less than 1 hectare) and on average they operate on 0.39 hectare, which implies that the income earned from agriculture produce for the majority of agricultural households is very low. This constant struggle of households with the credit system is vividly brought out by the All-India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS). The available data for 2002 and 2012 show that the reliance on non-institutional credit agencies by rural households was as high as 44 per cent in 2012 (Table 1.5). Given the huge credit demand, the Committee is of the view that this scenario may not have changed materially in the last couple of years. | Table 1.5: Percentage distribution of households' cash loans outstanding by credit agency | | Credit Agency | Rural | Urban | | 2002 | 2012 | 2002 | 2012 | | 1. Institutional Agencies | 57.1 | 56.0 | 75.1 | 84.5 | | of which: | | | | | | Co-operative Society/bank | 27.3 | 24.8 | 20.5 | 18.0 | | Commercial bank, including RRBs | 24.5 | 25.1 | 29.7 | 57.1 | | 2. Non-Institutional Agencies | 42.9 | 43.9 | 24.9 | 15.5 | | of which: | | | | | | Professional Moneylender | 19.6 | 28.2 | 13.2 | 10.5 | | Relatives and Friends | 7.1 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 4.2 | | Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | Disaggregated data on sources of cash loans show that in rural areas 61 per cent of households source such loans from non-institutional agencies, whereas in urban areas the number was 46 per cent. In rural areas, non-cultivators face comparatively greater difficulty in sourcing cash loans from institutional agencies than cultivators. Around one-third of rural households requiring credit approach professional moneylenders. Recommendation 1.6

The Committee recommends that a key component of the financial inclusion policy should be to improve the credit system for the underprivileged, particularly millions of poor agricultural households, so as to ensure a perceptible shift of credit demand from the informal to the formal sector. The vision of financial inclusion Driven by the government and financial regulatory initiatives, there has been substantial progress during the past decade in terms of financial inclusion indicators—be it in terms of branch penetration, account density or even credit and deposit numbers. Mobile telephony as a low-cost vehicle of communication and Aadhaar as unique biometric identifier have expanded rapidly. This will also aid focused and targeted distribution of benefits to the intended recipients, so as to improve the efficacy of distribution and minimise leakages. Notwithstanding these positives, several challenges remain to be addressed. First, in spite of the emphasis on supply, it does not appear to have adequately matched the demand. Nearly 35 per cent of the accounts across all banks were zero-balance accounts as on November 2015. Second, there are still substantial differences in exclusion across regions. Third, a significant gap in financial inclusion across gender persists. Fourth, interest-free banking remains an unaddressed concern. Fifth, access to finance for micro and small enterprises (MSEs) remains a major impediment. Sixth, technology does not appear to have been harnessed to the fullest extent in order to further the cause of financial inclusion. The Committee believes that the key ingredients of inclusion, the five Ps, as observed by Governor Rajan—a basic suite of products, ease of access and place of delivery, reasonable price of products, certain protection and the right incentive for formal financial entities to operate profitably in this space—still remain distant4. As aptly observed by Dr. Y.V. Reddy, harmonising the development objectives of the government with the central bank’s policy direction on inclusion with stability remains key to addressing various impediments in “achieving meaningful and universal financial inclusion”5. Against this backdrop, the Committee sets the vision of financial inclusion as ‘convenient’ access to a basket of basic formal financial products and services that should include savings, remittance, credit, government-supported insurance and pension products to small and marginal farmers and low-income households at reasonable cost with adequate protection progressively supplemented by social cash transfers besides increasing the access of micro and small enterprises to formal finance with a greater reliance on technology can cut costs and improve service delivery, such that by 2021 over 90 per cent of the hitherto underserved sections of society become active stakeholders in economic progress empowered by the formal finance. What follows The remainder of the Report is structured as follows. Chapter 2 discusses cross-country experiences in order to glean insights into key takeaways that can be suitably adapted to the Indian situation. Chapter 3 highlights the importance of agricultural credit and how policy interventions can further the financial inclusion agenda. Chapter 4 discusses the issue of credit flow to SMEs and what changes in products and policies can augment the flow of credit to this segment. The role of interest-free banking has been the focus of global policy discussions in recent times, an aspect that is dealt with in Chapter 5. The credit infrastructure and the changes that can be brought to bear on this area are examined in Chapter 6. Chapter 7 discusses the payments system. The demand side of the process and, in particular, the issue of Government-to-Person (G2P) payments is addressed in Chapter 8. Chapter 9 takes a close look at the issue of financial literacy and consumer protection and finally, Chapter 10 analyses governance issues that need to be addressed in the process.

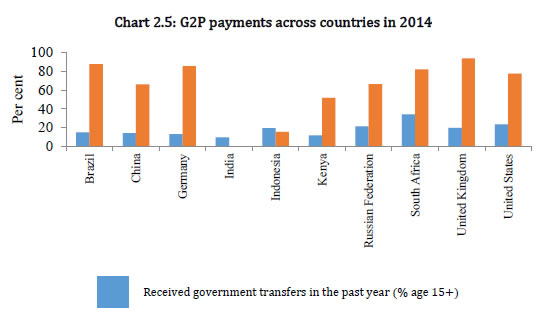

Chapter 2 : Cross-Country Experiences No one size fits all Globally, about 38 per cent of the adult population has no or very limited access to formal financial services. This makes a strong case for poor households to penetrate the boundary of formal finance. Loans or savings can help them to accelerate consumption, absorb unforeseen shocks such as health-related issues, make households investment in durable goods, home improvements or school fees (Collins et al., 2009). Insurance can also help them to cope better with risks. Moreover, macroeconomic evidence suggests that economies with deeper financial intermediation tend to grow faster and reduce income inequality (Beck et al. 2007). India does not compare very favourably with regard to financial inclusion even with peer emerging market economies In 2014, over 50 per cent of Indian adults held an account with a financial institution, compared to close to 70 per cent of adults in various BRICS economies, and an even higher percentages of adults in the US and UK. Similarly, in 2014, 6 per cent of Indian adults had borrowed from a formal financial institution in the past 12 months compared with 10 per cent or more in other BRICS economies (Chart 2.1). Furthermore, as of 2014 there were only 18 ATMs per 100,000 adult population in India against over 65 in South Africa and over 180 in Russia. Similarly, 10 per cent of individuals aged 15 years and above had made payments through debit cards in India as against approximately 40 per cent in South Africa (Chart 2.2). In terms of remittances, Kenya holds a leading position. In 2014, over 60 per cent of its adult population had received domestic remittances compared with less than 10 per cent in India. Similarly, only 3 per cent of the rural population in India had directly received wages into their accounts, as against 14 per cent in Brazil and 23 per cent in South Africa (Chart 2.3). The low use of accounts in India is also evidenced from the fact that in 2014 over 40 per cent of accounts did not witness any ‘movement’ (Chart 2.4).

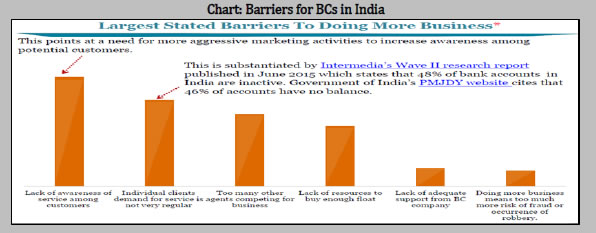

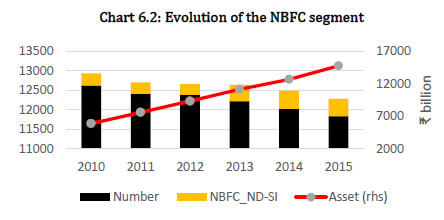

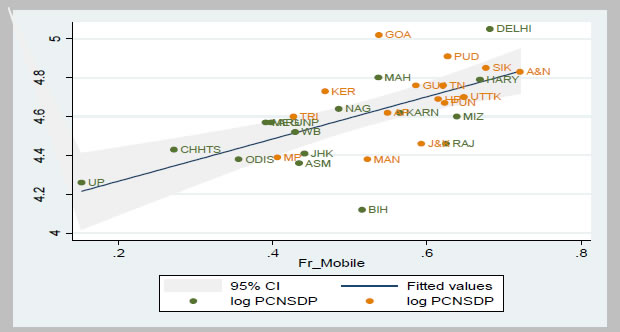

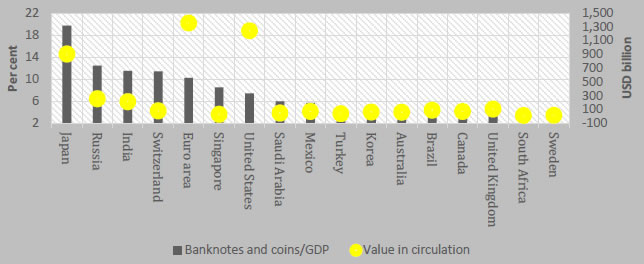

Recommendation 2.1