7.1 Access to safe, easy and affordable credit and other financial services by the poor and vulnerable groups, disadvantaged areas and lagging sectors is recognised as a pre-condition for accelerating growth and reducing income disparities and poverty. Access to a well-functioning financial system, by creating equal opportunities, enables economically and socially excluded people to integrate better into the economy and actively contribute to development and protect themselves against economic shocks. Despite the broad international consensus regarding the importance of access to finance as a crucial poverty alleviation tool1 , it is estimated that globally over two billion people are currently excluded from access to financial services (United Nations, 2006a). In most developing countries, a large segment of society, particularly low-income people, has very little access to financial services, both formal and semi-formal. As a consequence, many of them have to necessarily depend either on their own or informal sources of finance and generally at an unreasonably high cost. The situation is worse in most least developed countries (LDCs), where more than 90 per cent of the population is excluded from access to the formal financial system (United Nations, 2006a).

7.2 Theories of development advocate that financial development creates enabling conditions for growth through either a ‘supply-leading’ (financial development spurs growth) or a ‘demand-following’ (growth generates demand for financial products) channel. Earlier theories of development hypothesised that a rise in inequality was inevitable in the early stages of development. The early literature on the subject focussed on the need to develop an extensive financial system that could tap savings and then channel the funds so generated to a wide spectrum of activities. The modern development theory perceives the lack of access to finance as a critical factor responsible for persistent income inequality as well as slower growth. A large body of empirical literature suggests that developing the financial sector and improving access to finance may accelerate economic growth along with a reduction in income inequality and poverty. Without an inclusive financial system, poor individuals and small enterprises have to rely on their own limited savings and earnings to invest in their education and entrepreneurship to take advantage of growth opportunities (World Bank, 2008).

7.3 In an underdeveloped financial system, certain segments of the population experience difficulties in obtaining appropriate access to financial services. As a result, they have to resort to high cost informal sources such as moneylenders. This is particularly true for the sporadic financing requirements of low income households for non-productive consumption pur poses and other emergency requirements such as medical expenditure. Benefits of growth, therefore, tend to concentrate in the hands of those already served by the formal financial system. In mature financial systems on the other hand, financial institutions develop appraisal techniques and information gathering and sharing mechanisms, which then enable them to finance even those activities or firms or individuals that are at the margin, thereby promoting their growth-inducing productive activities. However, developed financial systems also encounter difficulties in serving low income groups for financing their consumption and other needs. The availability of external finance to potential entrepreneurs and small firms enables new entrants leading to increased competition to incumbents. This, in turn, encourages entrepreneurship and productivity.

7.4 Inclusive finance, including safe savings, appropriately designed loans for poor and low-income households and for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, and appropriate insurance and payments services can help people to enhance incomes, acquire capital, manage risk, and come out of poverty (United Nations, 2006b). It has been well recognised that access to financial services facilitates making and receiving financial payments and reduces transaction costs. Furthermore, access to financial services contributes to higher production and social protection, as the financial sector – through stored savings, credit and insurance – serves as a measure of crisis mitigation. Broader access to financial services has, however, attracted less attention despite the emphasis it has received in the theory.

7.5 In India, growth with equity has been the central objective right from the inception of the planning process. Accordingly, over the years, initiatives have been taken continuously by the Government and the Reserve Bank to address the issue of inclusive growth. Notwithstanding the rapid increase in overall GDP and per capita income in recent years, a significant proportion of the population in both rural and urban areas still experiences difficulties in accessing the formal financial system. Recent concerns have arisen from an inadequate reduction in poverty levels, sectoral divergences in growth and employment opportunities and tardy improvement in other social indicators, despite higher economic growth. The Eleventh Five Year Plan, therefore, re-emphasised the need for a more inclusive growth in order to ensure that the per capita income growth is more broad-based. The farming, micro, small and medium enterprises have immense potential to play a critical role in achieving the objective of faster and more inclusive growth as these sectors contribute to output and employment generation in a significant way with capacity to expand regionally diversified production and generating widely dispersed off-farm employment.

7.6 Bringing the larger population within the structured and organised financial system has explicitly been on the agenda of the Reserve Bank since 2005 (Mohan, 2006). While several central banks focus solely on inflation, many in developed and emerging economies alike, including India, also focus on growth. There is currently a perception that there are a large number of people, potential entrepreneurs, small enterprises and others, who may not have adequate access to the financial sector, which could lead to their marginalisation and denial of opportunity to grow and prosper. The Reserve Bank has, therefore, introduced various new measures to encourage the expansion of financial coverage in the country. Financial inclusion is considered essential for fostering economic growth in a more inclusive fashion.

7.7 In a fast growing economy, an important issue is how to sustain and diversify growth so that the risk to growth process is diversified across sectors. It is in this context that the search for potential sources of incremental growth, i.e., sectors that have difficulty in accessing financial services, assumes importance. Therefore, including such segments or sectors would, on the one hand, unleash their productive capacities, and on the other, would augment domestic demand on a sustainable basis driven by income and consumption growth from such sectors. This would also have strong inter-sectoral linkages.

7.8 Against the above backdrop, this chapter, drawing upon the theoretical developments, country experiences and empirical findings, seeks to examine key issues in financial inclusion/exclusion in India. Section II discusses the conceptual framework and measurement related issues. The nature, causes and consequences of financial exclusion are discussed in Section III. Section IV details the policy initiatives undertaken for promoting financial inclusion in India. Section V analyses the nature and extent of financial inclusion/exclusion in India. Operating cost of financial inclusion and the role of technology in financial inclusion are discussed in Section VI. Drawing from country experiences and empirical analysis in the Indian context, Section VII, as a way forward, makes some suggestions to promote financial inclusion in India. Section VIII concludes the chapter.

II. ACCESS TO FINANCE: CONCEPTUAL

FRAMEWORK

Concept and Definition

7.9 Defining financial inclusion is considered crucial from the viewpoint of developing a conceptual framework and identifying the underlying factors that lead to low level of access to the financial system. A review of literature suggests that there is no universally accepted definition of financial inclusion. As measuring inclusion is perceived to be difficult, financial inclusion is generally defined in terms of exclusion from the financial system. Early discussion on financial exclusion was preceded by social exclusion and focussed predominantly on the issue of geographical access to financial services, in particular banking outlets (Leyshon and Thrift, 1993). However, financial exclusion is not just about physical access caused by the changing topography of financial services. Therefore, the debate has now broadened to include all types of people who make little or no use of financial services and the processes of financial exclusion (Ford and Rowlingson, 1996; Kempson and Whyley, 1998).

7.10 The definitional emphasis of financial inclusion varies across countries and geographies,depending on the level of social, economic and financial development; the structure of stake holding in the financial sector; socio-economic characteristics of the financially excluded segments; and also the extent of the recognition of the problem by authorities or governments. Broadly, financial exclusion is construed as the inability to access necessary financial services in an appropriate form due to problems associated with access, conditions, prices, marketing or self-exclusion in response to discouraging experiences or perceptions of individuals/entities.

7.11 Definitions of financial exclusion in the literature vary depending on the dimensions such as ‘breadth’, ‘focus’ and ‘degree’ of exclusion. The ‘breadth’ dimension is the broadest of all definitions linking financial exclusion to social exclusion which defines financial exclusion as the processes that prevent poor and disadvantaged social groups from gaining access to the financial system (Leyshon and Thrift, 1995). The ‘focus’ dimension is in the middle of the spectrum that links financial exclusion to other dimensions of exclusion. It defines financial exclusion as the potential difficulties faced by some segments of population in accessing mainstream financial services such as bank accounts/home insurance (Meadows et al., 2004). The definitions laying emphasis on the ‘focus’ also vary significantly to include various segments of population such as individuals, households, communities, and businesses. The ‘degree’ dimension, which is the narrowest of all definitions of financial exclusion, defines financial exclusion as exclusion from particular sources of credit and other financial services including insurance, bill-payment services and accessible and appropriate deposit accounts (Rogaly, 1999). Finally, definitions of financial exclusion vary considerably according to the dimensions such as the concept of relativity, i.e., financial exclusion defined relative to some standard (i.e., inclusion). This line of thinking defines the problem of financial exclusion as that emanating from increased inclusion, leaving a minority of individuals and households behind (Kempson et al., 2000). Thus, there exists duality of hyper inclusion with some having access to a range of financial products and at the same time a minority lacking even the basic banking services. This phenomenon is observed mostly in developed countries with high degree of financial development.

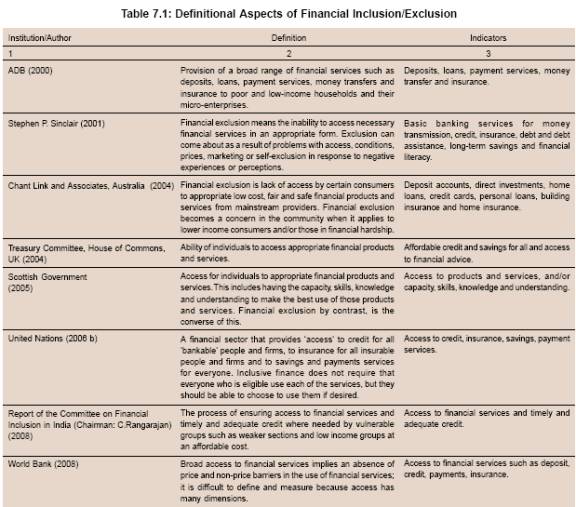

7.12 Over the years, several definitions of financial inclusion/exclusion have evolved (Table 7.1). The working or operational definitions of financial exclusion generally focus on ownership or access to particular financial products and services. The focus narrows down mainly to the products and services provided by the mainstream financial service providers (Meadows et al., 2004). Such financial products may include money transmission, home insurance, short and long-term credit and savings (Bridgeman, 1999). Furthermore, the operational definitions have also evolved from the underlying public policy concerns that many people, particularly those living on low income, cannot access mainstream financial products such as bank accounts and low cost loans, which, in turn, imposes real costs on them -often the most vulnerable people (H.M. Treasury, 2004).

7.13 The review of literature suggests that the most operational definitions are context-specific, originating from country-specific problems of financial exclusion and socio-economic conditions. Thus, the context-specific dimensions of financial exclusion assume importance from the public policy perspective. Furthermore, the definitions have witnessed a shift in emphasis from the earlier ones, which defined financial inclusion and exclusion largely in terms of physical access, to a wider definition covering access to and use and understanding of products and services.

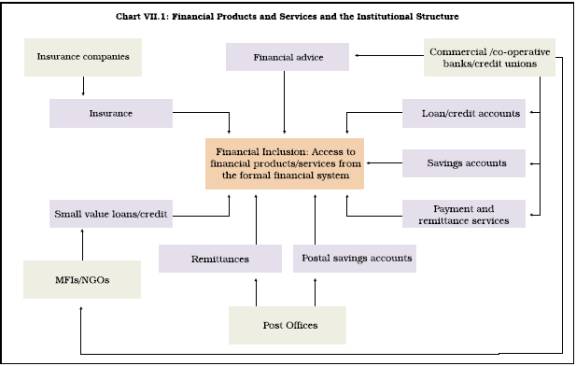

7.14 The operational definition of financial inclusion, based on the access to financial products or services, also underscores the role of financial institutions or service providers involved in the process. The anatomy of various financial products or services and the institutional structure is schematically presented in Chart VII.1.

Measurement of Financial Inclusion/Exclusion

7.15 While the importance of financial inclusion has been widely accepted, much less is known about how inclusive the financial systems are and who has access to which financial services. The literature on financial inclusion lacks a comprehensive measure that can be used to indicate the extent of financial inclusion across countries. Though indicators of the depth of banking system, capital markets, and insurance sector are widely available, there is less information available about the degree of financial inclusiveness. Lack of information is more conspicuous in developing countries where there is little systematic information on who is served by the formal financial sector, which financial institutions or services are the most effective at supporting access by poor households and small enterprises, or what practical and policy barriers may be hindering the accessibility. Individual indicators, viz., number of bank accounts and number of bank branches that are generally used as measures of financial inclusion, can provide only partial information on the level of financial inclusion in an economy. Financial services or products rendered by banks, postal savings banks, credit unions, finance companies, micro-finance institutions (MFIs), and other formal and quasi-formal non-bank institutions generally form the basis for measuring the financial inclusion.

7.16 It is often observed that people may have access to financial services, but may not wish to use them. Such voluntarily excluded persons, it is argued, should be included in measures of access even if they do not use financial services. However, even among the ‘voluntarily excluded’, this may in reality be because such services are unaffordable, unsuited to their needs, or because the potential users fear that they will be declined upon request. Among the ‘involuntarily excluded’ from services such as credit, some represent high credit risk that lenders are discouraged to prudently serve them.

7.17 There are various measures of access to finance. For instance, access to finance can be measured in terms of access to certain institutions (such as banks, insurance companies, and MFIs or in terms of access to the functions that such institutions perform, or the services that they provide (such as payments services, savings or loans and credits). Yet another approach is to look at details on the uses of specific financial products such as debit cards, credit cards, life insurance and home mortgages, among others. However, these are highly country-specific. The core access indicators often used are generally based on institutional distinctions concerning specifically the degree of formality of the financial institutions (World Bank, 2008).

7.18 Access covers a range of institutions from the more formal to less formal. At the one end of the spectrum are banks or near banks which are often defined as formal financial institutions which can provide multiple financial services to their clients, including deposits, payments and credit services. The attributes of banks and near banks are broadly comparable across countries. Other formal financial service providers are all other legal entities licensed to provide financial services. They are registered and subject to some reporting requirements. Thus, in the case of credit, this may include consumer finance companies, credit card companies or credit unions. Informal providers of financial services are other organised providers of financial services that are not registered as financial intermediaries and not subject to any oversight. Moneylenders and cheque cashing outlets, which are not regulated financial institutions, belong to this categor y. Based on the above characteristics of the financial service providers, the following measures/indicators can be summarised as the basic indicators used to measure the extent/ magnitude of financial exclusion in a country.

7.19 Core and headline indicators place a given population along a continuum of access, depending on its usage of formal, semi-formal, and informal financial services, and those excluded from the use of financial services. The access to finance could be divided into four segments (i) the proportion of the population that uses a bank or bank like institution; (ii) the population which uses service from non-bank ‘other formal’ financial institutions, but does not use bank services; (iii) the population which only uses services from informal financial service providers; (iv) percentage of population transacting regularly through formal financial instruments; and (v) the population which uses no financial services.

7.20 The second group of core indicators looks in greater detail at the kinds of financial services offered. This functional perspective enables a focus on specific service needs and their gradation in order of priority from less to more developed financial environment. These additional core indicators provide augmented understanding of the nature and depth of financial services. The financial service functions identified to be used as the basis for indicators are: (i) transactions or payment services; (ii) savings (deposit) and investment services; and (iii) loan or credit services. Risk transformation services such as insurance could arguably be added. However, it is conceptually similar to a sophisticated savings and credit product.

7.21 To sum up, no universally accepted definition of financial inclusion is available. Since measuring inclusion is perceived to be difficult, financial inclusion has generally been defined in terms of exclusion from the financial system. The working or operational definitions of financial exclusion generally focus on ownership or access to particular financial products and services.

7.22 There is no single comprehensive measure that can be used to indicate the extent of financial inclusion across economies. Specific indicators such as number of bank accounts, number of bank branches, that are generally used as measures of financial inclusion, can provide only partial information on the level of financial inclusion in an economy. Another approach is to look at details on the uses of specific financial products such as debit cards, credit cards, life insurance, and home mortgages, but these are highly country specific.

III. NATURE, CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF FINANCIAL EXCLUSION

Nature and Causes

7.23 The nature and forms of exclusion and the factors responsible for it are varied and, thus, no single factor could explain the phenomenon. The principal barriers in the expansion of financial services are often identified as physical access, high charges and penalties, conditions attached to products which make them inappropriate or complicated and perceptions of financial service institutions which are thought to be unwelcoming to low income people (Sinclair, 2001). These barriers to inclusion have not been constructed deliberately; they are a result of the structural operation of the financial services industry. Kempson et al. (2000) analyse a range of physical and geographical barriers to financial inclusion and a broad range of other factors that can contribute to financial exclusion for different products and individuals under certain circumstances. A number of ‘dimensions’ or ‘forms’ of financial exclusion have been identified. The critical dimensions of financial exclusion include: (i) access exclusion- restriction of access through the process of risk management (by financial services providers); (ii) condition exclusion - conditions attached to financial products which make them inappropriate for the needs of some segments of population; (iii) price exclusion- some people can only gain access to financial products at prices they cannot afford; (iv) marketing exclusion - some people are effectively excluded by targeted marketing and sales; and (v) self-exclusion - people decide not to opt for a financial product because of the fear of refusal to access by the service providers (Kempson and Whyley, 1999; Kempson et al., 2000; Connolly and Hajaj, 2001).

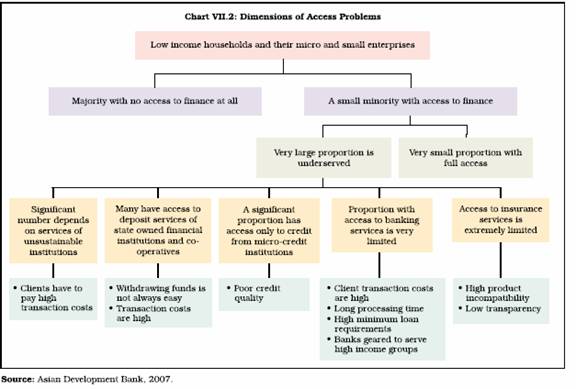

7.24 Measuring an individual’s or household’s usage of a particular financial service at a given time may not reveal whether exclusion is short-term or the result of a long-term process, nor whether access is diminishing or improving (Chant Link and Associates, 2004). Thus, financial exclusion is perceived as an ongoing process in terms of vulnerability to exclusion, rather than simply having access to certain financial services or not. In particular, financial exclusion may be a long-term phenomenon for many consumers or even a life-long process (Connolly and Hajaj, 2001). For families with particular constellations of socioeconomic characteristics, it may extend beyond the lifetime of an individual family member and become inter-generational. It has generally been recognised that it is the poorer sections of the population that do not have access to financial services - formal or informal. However, in many countries, many non-poor individuals, micro, small and medium entrepreneurs also have difficulty in accessing financial services. The most conspicuous dimension is that many of the low-income segments of the population do not have access to even the very basic financial services. Even amongst those who have access to finance, most are underserved in terms of quality and quantity of products and services and significant proportion of low-income households is dependent on unsustainable, subsidy-dependent and poorly performing institutions (Chart VII.2).

7.25 Exclusion may also have resulted from a variety of structural factors such as unavailability of products suiting their requirements, stringent documentation and collateral requirements and increased competition in financial services. There has also been particular emphasis on socio-cultural factors that matter for an individual to access financial services (United Nations, 2006b). Substantial

proportion of households, especially those with low income and those living in rural and remote areas, is at present outside the ambit of the formal financial system in many countries. Literature on financial inclusion/exclusion has identified a number of factors that affect efforts to expand access to financial services (Box VII.1).

7.26 Apart from the supply side factors, demand side factors also have a significant bearing on the extent of financial inclusion. A higher share of population below the poverty line results in lower demand for financial services as the poor may not have savings to place as deposit in savings banks. Thus, low income leads to low demand for financial services, particularly savings products. Likewise, at low levels of development, investment activity may be low and hence, may lead to low demand for credit from banks and other formal financial institutions. However, as poverty levels decline and households move into higher income brackets, their propensity to save increases, which, in turn, leads to higher demand for financial services both for saving and investment purposes.

7.27 Financial inclusion is also influenced by specific credit needs of various segments of the society. The demand for credit by the people arises for a number of activities such as housing, microenterprises, agricultural operations and consumption needs. Owing to difficulties in accessing formal sources of credit, the poor individuals and small and microenterprises usually rely on their personal savings or internal resources to invest in housing, health and education, and entrepreneurial activities to make use of growth opportunities (World Bank, 2008).

7.28 In India, the financially excluded sections comprise largely marginal farmers, landless labourers, oral lessees, self-employed and unorganised sector enterprises, urban slum dwellers, migrants, ethnic minorities and socially excluded groups, senior citizens and women. Some of the important causes of relatively low extension of institutional credit in the rural areas are risk perception, cost of its assessment and management, lack of rural infrastructure, and vast geographical spread of the rural areas with more than half a million villages, some sparsely populated (Mohan, 2006).

Box VII.1 Factors Affecting Access to Financial Services

A number of factors affecting access to financial services have been identified in many countries. These are:

• Gender issues: Access to credit is often limited for women who do not have, or cannot hold title to assets such as land and property or must seek male guarantees to borrow.

• Age factor: Financial service providers usually target the middle of the economically active population, often overlooking the design of appropriate products for older or younger potential customers.

• Legal identity: Lack of legal identities like identity cards, birth certificates or written records often exclude women, ethnic minorities, economic and political refugees and migrant workers from accessing financial services.

• Limited literacy: Limited literacy, particularly financial literacy, i.e., basic mathematics, business finance skills as well as lack of understanding often constrain demand for financial services.

• Place of living: Although effective distance is as much about transportation infrastructure as physical distance, factors like density of population, rural and remote areas, mobility of the population (i.e., highly mobile people with no fixed or formal address), insurgency in a location, etc., also affect access to financial services.

• Psychological and cultural barriers: The feeling that banks are not interested to look into their cause has led to self-exclusion for many of the low income groups. However, cultural and religious barriers to banking have also been observed in some of the countries.

• Social security payments: In those countries where the social security payment system is not linked to the banking system, banking exclusion has been higher.

• Bank charges: In most of the countries, transaction is free as long as the account has sufficient funds to cover the cost of transactions made. However, there are a range of other charges that have a disproportionate effect on people with low income.

• Terms and conditions: Terms and conditions attached to products such as minimum balance requirements and conditions relating to the use of accounts often dissuade people from using such products/services.

• Level of income: Financial status of people is always important in gaining access to financial services. Extremely poor people find it difficult to access financial services even when the services are tailored for them. Perception barriers and income discrimination among potential members in group-lending programmes may exclude the poorer members of the community.

• Type of occupation: Many banks have not developed the capacity to evaluate loan applications of small borrowers and unorganised enterprises and hence tend to deny such loan requests.

• Attractiveness of the product: Both the financial services/products (savings accounts, credit products, payment services and insurance) and how their availability is marketed are crucial in financial inclusion.

References:World Bank, 2008; Asian Development Bank, 2007; and Kempson et al., 2004.

Costs and Consequences of Financial Exclusion

7.29 Broadly, the issue of cost of financial exclusion may be conceived from two angles, which are intertwined. First, the exclusion may have cost for individuals/entities in terms of loss of opportunities to grow in the absence of access to finance or credit. Second, from the societal or the national perspective, exclusion may lead to aggregate loss of output or welfare and the country may not realise its growth potential. The more tangible outcomes of financial exclusion include cost and security issues in managing cash flow and payments, compromised standard of living resulting from lack of access to short-term credit, higher costs associated with using informal credit, increased exposure to unethical, predatory and unregulated providers, vulnerability to uninsured risks, and long-term or extended dependence on welfare as opposed to savings (Chant Link and Associates, 2004).

7.30 Access to a bank account, credit and insurance are now widely regarded as essential supports for personal financial management and for undertaking transactions in modern societies (Speak and Graham, 1999). According to the Treasury Committee, UK (2006), financial exclusion can impose significant costs on individuals, families and society as a whole. These include (i) barriers to employment as employers may require wages to be paid into a bank account; (ii) opportunities to save and borrow can be difficult to access; (iii) owning or obtaining assets can be difficult; (iv) difficulty in smoothening income to cope with shocks; and (v) exclusion from mainstream society.

7.31 In terms of cost to the individuals, financial exclusion leads to higher charges for basic financial transactions like money transfer and expensive credit, besides all round impediments in basic/ minimum transactions involved in earning livelihood and day to day living. It could also lead to denial of access to better products or services that may require a bank account. It exposes the individual to the inherent risk in holding and storing money – operating solely on a cash basis increases vulnerability to loss or theft. Individuals/families could get sucked into a cycle of poverty and exclusion and turn to high cost credit from moneylenders, resulting in greater financial strain and unmanageable debt. At the wider level of the society and the nation, financial exclusion leads to social exclusion, poverty as well as all the other associated economic and social problems. Thus, financial exclusion is often a symptom as well as a cause of poverty. Financial exclusion is not evenly distributed throughout society; it is concentrated among the most disadvantaged groups and communities and, as a result, contributes to a much wider problem of social exclusion.

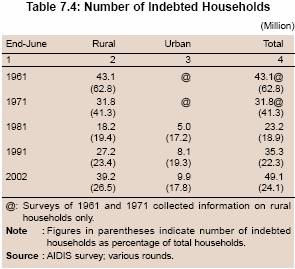

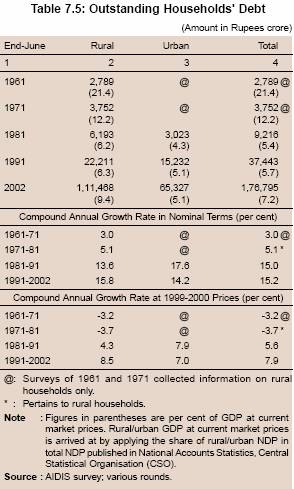

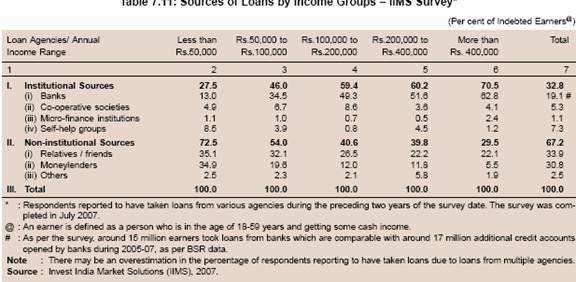

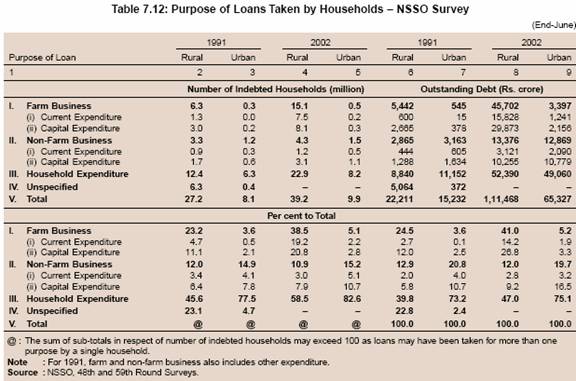

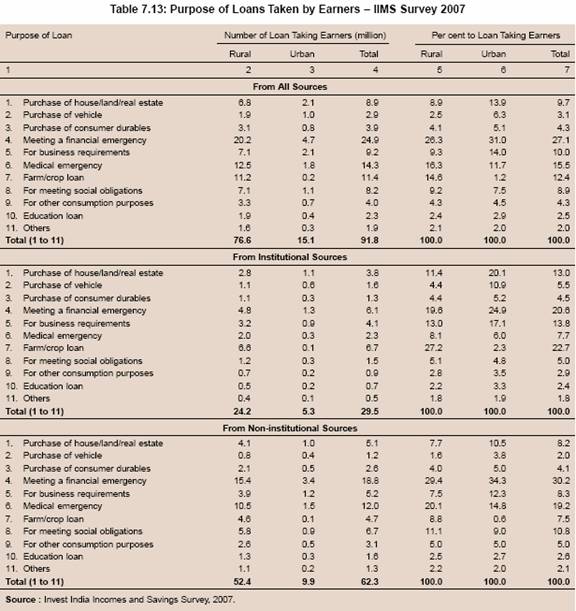

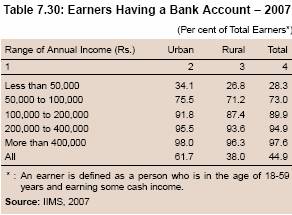

7.32 A significant portion of demand for credit by rural households arises in order to ease the financial burden of crop failures, illness or death, and health care. In the case of microenterprises, credit may be needed to achieve a reasonable and viable scale of activities. The rising entrepreneurship spanning rural, semi-urban and urban areas, particularly in the unorganised and informal sectors may give rise to large potential demand for credit. The evidence on the demand for credit in India suggests that medical and financial emergencies are the major reasons for household borrowings. Medical emergencies were particularly high for the lowest income quartile (IIMS, 2007)2 . Thus, the difficulty in obtaining finance from formal sources has major social implications.

7.33 Another cost of financial exclusion is the loss of business opportunity for banks, particularly in the medium-term. Banks often avoid extending their services to lower income groups because of initial cost of expanding the coverage which may sometimes exceed the revenue generated from such operations. These business related concerns of banks were, however, meaningful when technology development was at a nascent stage and expanding the coverage of financial services required substantial initial investment. The strides in technology have now reduced the required initial investment in a significant manner. What is required is to explore the appropriate technology which is suitable to socio-economic conditions of the region under consideration. Moreover, availability and usage of financial services by the otherwise excluded population groups would lead to increase in their income levels and savings. This, in turn, would have the potential to increase savings deposits as well as credit demand, implying profitable business for banks in the medium-term.

7.34 Two other factors have often been cited as the consequences of financial exclusion. First, it complicates day-to-day cash flow management -being financially excluded means households, and micro and small enterprises deal entirely in cash and are susceptible to irregular cash flows. Second, lack of financial planning and security in the absence of access to bank accounts and other saving opportunities for people in the unorganised sector limits their options to make provisions for their old age. From the macroeconomic standpoint, being without formal savings can be problematic in two respects. First, people who save by informal means rarely benefit from the interest rate and tax advantages that people using formal methods of savings enjoy. Second, informal saving channels are much less secure than formal saving facilities. Those who can afford it least, suffer the highest risk. The resultant lack of savings and saving avenues means recourse to non-formal lenders such as moneylenders. This, in turn, could lead to two adverse consequences – (a) exposure to higher interest rates charged by informal lenders; and (b) the inability of customers to service the loans or to repay them. As loans from non-formal lenders are often secured against the borrower’s property, this raises the problem of inter-linkage between two apparently separate markets. Judged in this specific context, financial exclusion is a serious concern among low-income households, mainly located in rural areas (Mohan, 2006).

7.35 To sum up, the nature and forms of exclusion and the factors responsible for it are varied and, thus, no single factor could explain the phenomenon. The principal barriers in the expansion of financial services are often identified as physical access, high charges and penalties, conditions attached to products which make them inappropriate or complicated and perceptions of financial service institutions which are thought to be unwelcoming to low income people. There has also been particular emphasis on socio-cultural factors that matter for an individual to access financial service. The most conspicuous dimension of exclusion is that a majority of the low-income population do not have access to the very basic financial services. Even amongst those who have access to finance, most of them are underserved in terms of quality and quantity of products and services. The critical dimensions of financial exclusion include access exclusion, condition exclusion (conditions attached to financial products), price exclusion, and self exclusion because of the fear of refusal to access by the service providers. The financial exclusion process becomes self-reinforcing and can often be an important factor in social exclusion, especially for communities with limited access to financial products, particularly in rural areas. Apart from the above mentioned supply side factors, demand side factors may also significantly affect the extent of financial inclusion. For instance, low level of income and hence low savings would result in lower deposits. Similarly, at low level of income, the ability to borrow is affected because of low repayment capacity and inability to provide collateral. In the Indian context, both demand and supply side factors have an important bearing on the usage of financial/banking services.

7.36 The issue of cost has been conceived from two angles, which are inter-twined. First, the exclusion may have cost on the individuals/entities in terms of loss of opportunities to grow in the absence of access to finance or credit. Second, from the societal or the national perspective, exclusion may lead to aggregate loss of output or welfare and the country may not realise its growth potential. Recognising the implicit and explicit cost of financial exclusion across the globe, many countries have initiated measures to deal with the same.

IV. INITIATIVES FOR FINANCIAL INCLUSION IN INDIA

7.37 As discussed in Chapter III, India has a long history of banking development. After Independence, the major focus of the Government and the Reserve Bank was to develop a sound banking system which could support planned economic development through mobilisation of resources/deposits and channel them into productive sectors. Accordingly, the Government’s desire to use the banking system as an important agent of change was at the core of most policies that were formulated after Independence. The planning strategy recognised the critical role of the availability of credit and financial services to the public at large in the holistic development of the country with the benefits of economic growth being distributed in a democratic manner. In recognition of this role, the authorities modified the policy framework from time to time to ensure that the financial services needs of various segments of the society were met satisfactorily.

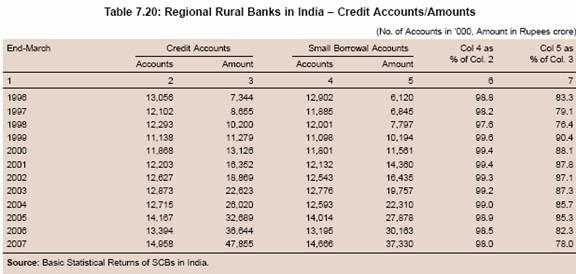

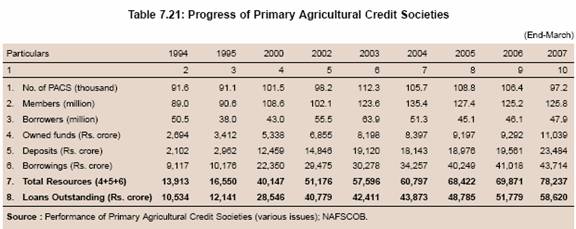

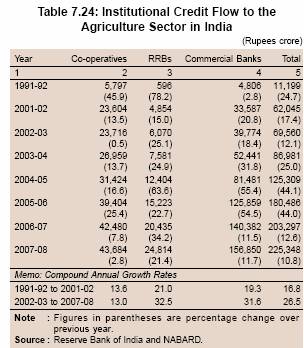

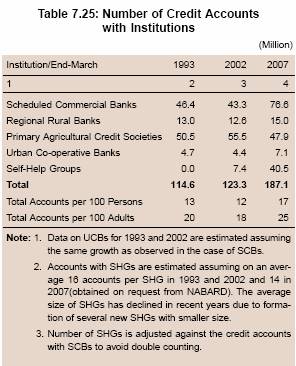

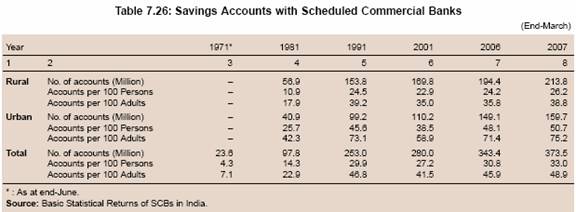

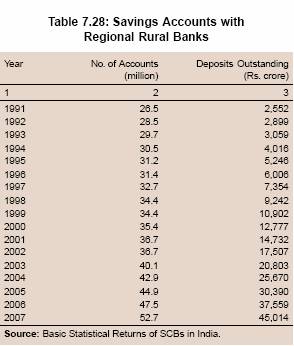

7.38 In order to expand the credit and financial services to the wider sections of the population, a wide network of financial institutions has been established over the years. The organised financial system comprising commercial banks, regional rural banks (RRBs), urban co-operative banks (UCBs), primary agricultural credit societies (PACS) and post offices caters to the needs of financial services of the people. Besides, MFIs, self-help groups (SHGs) also meet the financial service requirements of the poorer segments. Furthermore, development of the institutional framework in recent years has focussed on new models of expanding financial services involving credit dispensation using multiple channels such as civil society organisations (CSOs), non-government organisations (NGOs), post offices, farmers’ clubs, and panchayats as business facilitators/correspondents. Specific financial instruments/products were also developed in order to promote financial inclusion.

Overall Approach

7.39 Financial inclusion in the Indian context implies the provision of affordable financial services, viz., access to payments and remittance facilities, savings, loans and insurance services by the formal financial system to those who tend to be excluded. Besides access, emphasis is also placed on affordability (low cost) of financial services such as savings, loan, and remittance to the underprivileged segments of the population. Although the term ‘financial inclusion’ was not in vogue in India then, since the late 1960s both the Government and the Reserve Bank have been concerned about the non-availability of banking facilities to the under-privileged and weaker sections of the society. Accordingly, several initiatives have been taken over time such as nationalisation of banks, prescription of priority sector targets, lending to weaker sections at concessional rates, and initiation of the lead bank scheme. These initiatives were undertaken at different points in time to expand the outreach of banking facilities and increase the flow of credit to the rural areas. However, the broad approach towards financial inclusion followed in India in the 1970s and the 1980s was more oriented towards credit requirements of specific sectors/segments and there was relatively low emphasis on individual/household level inclusion. The Indian financial system essentially catered to the needs of planned development in a mixed-economy framework, where the Government sector had a predominant role in economic activity. The focus of banking policy during the 1990s and up to the early 2000s was more on creating a strong and efficient banking system. However, once the financial health of the banking system was restored, focussed attention was again paid towards promotion of financial inclusion.

7.40 The recent approach focuses on financial inclusion on the individual and household level (Box VII.2). The important difference in the recent focus on financial inclusion is the adoption of market oriented approach that recognises the importance of business consideration of banks and other financial institutions for the long-term sustainability of the process. The Annual Policy Statement for the Year 2005-06 of the Reserve Bank observed that although there had been expansion, greater competition and diversification of ownership of banks leading to both enhanced efficiency and systemic resilience, there were legitimate concerns with regard to the banking practices that tended to exclude vast sections of population, in particular pensioners, self-employed and those employed in the unorganised sector. The Statement further observed that while commercial considerations were important, the banks had been bestowed with several privileges, especially of seeking public deposits on a highly leveraged basis, and therefore, should be obliged to provide banking services to all segments of the population on an equitable basis.

7.41 The broad strategy for financial inclusion in India in recent years comprises the following elements: (i) encouraging penetration into unbanked and backward areas and encouraging agents and intermediaries such as NGOs, MFIs, CSOs and business correspondents (BCs); (ii) focussing on a decentralised strategy by using existing arrangements such as State Level Bankers’ Committee (SLBC) and district consultative committee (DCC) and strengthening local institutions such as co-operatives and RRBs; (iii) using technology for furthering financial inclusion; (iv) advising banks to open a basic banking ‘no frills’ account; (vi) emphasis on financial literacy and credit counselling; and (vii) creating synergies between the formal and informal segments (Thorat, 2008).

7.42 Various initiatives undertaken could broadly be categorised into three phases. In the first phase starting in the late 1960s through the 1980s, the focus was on channelling of credit to the neglected sectors of the economy. Special emphasis was also laid on weaker sections of the society. In the second phase spanning the early 1990s through March 2005, the focus was mainly on strengthening the financial institutions as part of financial sector reforms. Financial inclusion in this phase was encouraged mainly by the introduction of SHG-bank linkage programme in the early 1990s and Kisan Credit Cards (KCCs) for providing credit to farmers. In the third phase, beginning in April 2005, ‘financial inclusion’ was explicitly made as a major policy objective and thrust was on providing safe facility of savings deposits through ‘no frills’ accounts.

Progress till 1990

7.43 Before 1990, several initiatives were undertaken for enhancing the use of the banking system for sustainable and equitable growth. These included nationalisation of private sector banks, introduction of priority sector lending norms, the Lead Bank Scheme, branch licensing norms with focus on rural/semi-urban branches, interest rate ceilings for credit to the weaker sections and creation of specialised financial institutions to cater to the requirement of the agriculture and the rural sectors having bulk of the poor population. The announcement of the policy of social control over banks was made in December 1967 with a view to securing a better alignment of the banking system with the needs of economic policy. The National Credit Council was set up in February 1968 mainly to assess periodically the demand for bank credit from various sectors of the economy and to determine the priorities for grant of loans and advances. Social control of banking policy was soon followed by the nationalisation of major Indian banks in 1969. The immediate tasks set for the nationalised banks were mobilisation of deposits on a massive scale and lending of funds for all productive activities. A special emphasis was laid on providing credit facilities to the weaker sections of the economy.

Box VII.2 Financial Inclusion in India – Key Elements

(i) Financial inclusion is delivery of banking services at an affordable cost to the vast sections of disadvantaged and low income groups. Unrestrained access to public goods and services is the sine qua non of an open and efficient society. As banking services are in the nature of public good, it is essential that availability of banking and payment ser vices to the entire population without discrimination is the prime objective of the public policy (Leeladhar, 2006).

(ii) Financial exclusion signifies lack of access by certain segments of the society to appropriate, low-cost, fair and safe financial products and services from mainstream providers. Financial exclusion is thus a key policy concern, because the options for operating a household budget, or a micro/small enterprise, without mainstream financial services can often be expensive. This process becomes self- reinforcing and can often be an important factor in social exclusion, especially for communities with limited access to financial products, particularly in rural areas (Mohan, 2006).

(iii) Financial inclusion means the provision of affordable financial services, viz., access to payments and remittance facilities, savings, loans and insurance services by the formal financial system to those who tend to be excluded (Thorat, 2006).

(iv) The process of financial inclusion consists of seeking each household and offering their inclusion in the banking system (Reddy, 2007).

(v) The process of ensuring access to financial services and timely and adequate credit where needed by vulnerable groups such as weaker sections and low income groups at an affordable cost (The Committee on Financial Inclusion, Chairman: Dr. C. Rangarajan, 2008).

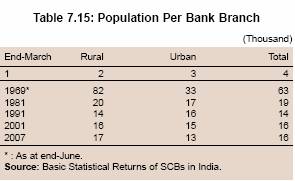

7.44 The administrative framework for rural lending in India was provided by the Lead Bank Scheme introduced in 1969, which was an important step towards implementation of the two-fold objectives of deposit mobilisation on an extensive scale and stepping up of lending to weaker sections of the economy. Realising that the flow of credit to employment oriented sectors was inadequate, the priority sector guidelines were issued to the banks by the Reserve Bank in the late 1960s to step up the flow of bank credit to agriculture, small-scale industry, self-employed, small business and the weaker sections within these sectors. The target for priority sector lending was gradually increased to 40 per cent of advances in the case of domestic banks (32 per cent, inclusive of export credit, in the case of foreign banks) for specified priority sectors. Sub-targets under the priority sector, along with other guidelines including those relating to Government sponsored programmes, were used to encourage the flow of credit to the identified vulnerable sections of the population such as scheduled castes, religious minorities and scheduled tribes. The Differential Rate of Interest (DRI) Scheme was instituted in 1972 to provide credit at concessional rate to low income groups in the country (see Chapter III for details).

7.45 Since the 1970s, the promotional aspects of banking policy have come into greater prominence. The major emphasis of the branch licensing policy during the 1970s and the 1980s was on expansion of commercial bank branches in rural areas, resulting in a significant expansion of bank branches and decline in population per branch. The branch expansion policy was designed, inter alia, as a tool for reducing inter-regional disparities in banking development, deployment of credit and urban-rural pattern of credit distribution. In order to encourage commercial banks and other institutions to grant loans to various categories of small borrowers, the Reserve Bank promoted the establishment of the Credit Guarantee Corporation of India in 1971 for providing guarantees against the risk of default in repayment. The scheme, however, was subsequently discontinued.

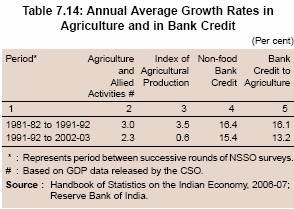

7.46 The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) was set up in 1982 mainly to provide refinance to the banks extending credit to agriculture. RRBs, which were set up in 1975 to cater, inter alia, to the credit requirements of the rural poor, have recently been restructured.

Recent Initiatives

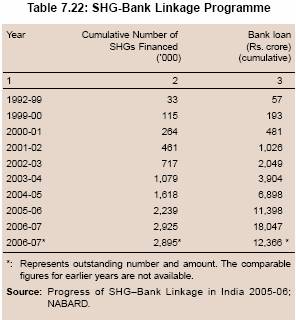

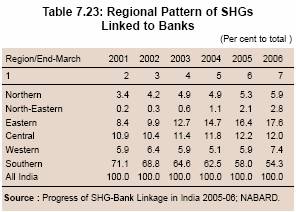

7.47 With the onset of economic reforms in the beginning of the 1990s, a strong and resilient financial sector was considered necessary for accelerating the growth momentum in the country and also for expanding the coverage of financial services in a sustainable manner. Accordingly, the financial sector refor m process placed more emphasis on creating a strong, vibrant and competitive banking system. An important step to bring financially excluded people within the fold of formal financial sector was the promotion of micro-finance in India. The SHG-bank linkage programme was launched by NABARD in 1992, with policy support from the Reserve Bank, to facilitate collective decision making by the poor and provide ‘door step’ banking. Banks, as wholesalers of credit, were to provide the resources, while the NGOs were to act as agencies to organise the poor, build their capacities and facilitate the process of empowering them (Box VII.3).

7.48 To further promote the SHG-bank linkage programme in the country, banks were advised in 1998 that SHGs that were engaged in promoting the saving habits among their members would be eligible to open savings bank accounts and that such SHGs need not necessarily have availed of credit facilities from banks before opening savings bank accounts. Subsequent to the Monetary and Credit Policy announcement for the year 1999-2000, banks were

Box VII.3 Self-Help Group – Bank Linkage Programme

An SHG is a group of about 15 to 20 people from a homogenous class who join together to address common issues. They involve voluntary thrift activities on a regular basis, and use of the pooled resource to make interest-bearing loans to the members of the group. In the course of this process, they imbibe the essentials of financial intermediation and also the basics of account keeping. The members also learn to handle resources of size, much beyond their individual capacities. They begin to appreciate the fact that the resources are limited and have a cost. Once the group is stabilised, and shows mature financial behaviour, which generally takes up to six months, it is considered for linking to banks. Banks are encouraged to provide loans to SHGs in cer tain multiples of the accumulated savings of the SHGs. Loans are given without any collateral and at interest rates as decided by banks. Banks find it comfortable to lend money to the groups as the members have already achieved some financial discipline through their thrift and internal lending activities. The groups decide the terms and conditions of loan to their own members. The peer pressure in the group ensures timely repayment and becomes social collateral for the bank loans.

Generally, the SHGs need self-help promoting institutions (SHPIs) to promote and nurture them. These SHPIs include various NGOs, banks, farmers’ clubs, government agencies, self-employed individuals and federations of SHGs. However, some SHGs have also been formed without any assistance from such SHPIs.

There are three different models that have emerged under the linkage programme:

• Model I: This involves lending by banks directly to SHGs without intervention/facilitation by any NGO.

• Model II: This envisages lending by banks directly to SHGs with facilitation by NGOs and other agencies.

• Model III: This involves lending, with an NGO acting as a facilitator and financing agency.

Model II accounted for around 74 per cent of the total linkage at end-March 2007, while Models I and III accounted for around 20 per cent and 6 per cent, respectively.

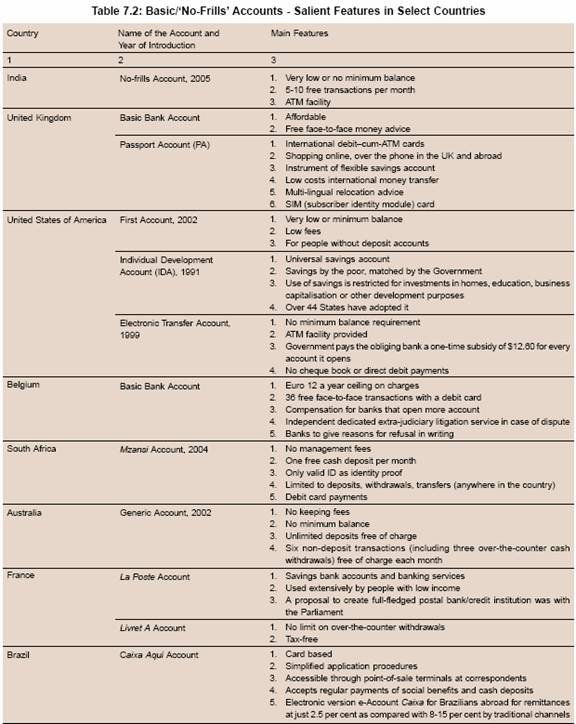

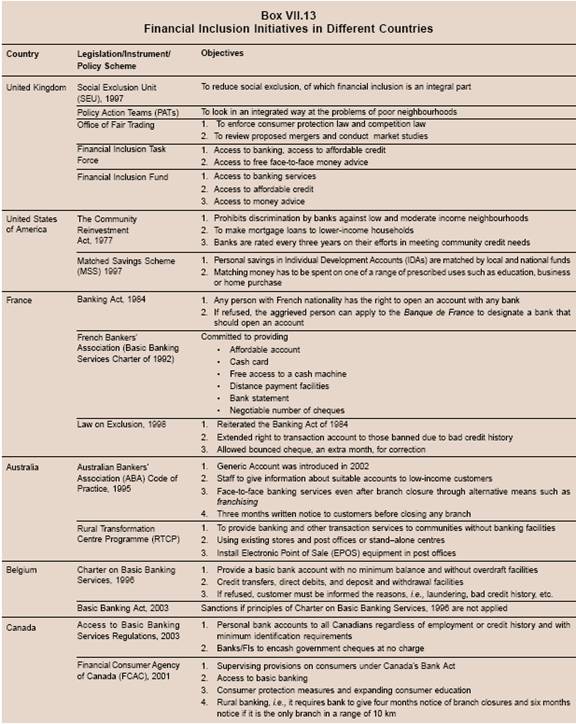

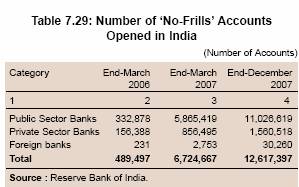

7.50 The process of financial inclusion received further impetus in November 2005, when banks were advised to make available a basic banking ‘no-frills’ account with low or nil minimum balances as well as charges to expand the outreach of such accounts to vast sections of the population. The low cost or free of cost account is internationally considered to be helpful in expanding the access of banking services, particularly to the low income groups. Similar types of accounts, though with different names, have also been extended by banks in various other countries with a view to making financial services accessible to the common man either at the behest of banks themselves or the respective Governments (Table 7.2).

7.51 In order to ensure that persons belonging to low income groups, both in urban and rural areas do not encounter difficulties in opening bank accounts, the know your customer (KYC) procedure for opening accounts was simplified for those accounts with balances not exceeding Rs.50,000 and credit limits not exceeding Rs.100,000 in a year. The simplified procedure allowed introduction by a customer on whom the full KYC drill had already been done.

7.52 Besides the KCCs, which were introduced in 1998, banks were advised in 2005 to consider introduction of a General Credit Card (GCC) facilityup to Rs.25,000 at their rural and semi-urban branches. Under GCC, based on the assessment of household cash flows, the limits are sanctioned without insistence on security or purpose. The credit facility is in the nature of revolving credit entitling the holder to withdraw up to the limit sanctioned. Based on assessment of household cash flows, the limits are sanctioned. Interest rate on the facility is completely deregulated. Fifty per cent of GCC loans are treated as priority sector lending.

7.53 The SLBC identifies one or more districts for 100 per cent financial inclusion.3 The responsibility is given to the banks in the area for ensuring that all those who want to have a bank account are provided with one by allocating the villages to the different banks. In April 2008, SLBCs reported achieving 100 per cent financial inclusion in 134 districts in 18 States and 6 Union Territories (UTs) of the country. The Reserve Bank is undertaking an evaluation of the progress made in these districts by independent external agencies to draw lessons for further action in this regard.

7.54 In Januar y 2006, the Reser ve Bank, permitted banks to utilise the services of NGOs/ SHGs, MFIs (other than NBFCs) and other civil society organisations as inter mediaries for providing financial and banking services through the use of business facilitator (BF) and business correspondent (BC) models. In April 2008, banks were permitted to engage retired bank employees, ex-servicemen and government employees as BCs, subject to appropriate due diligence. The BC model allows banks to do ‘cash in - cash out’ transactions at a location much closer to the rural population, thus, addressing the last mile problem. Banks are also entering into agreements with Indian Postal authorities for using the enormous network of post offices as BCs, thereby increasing their outreach. In order to provide social security to vulnerable groups, in some cases banks have provided, in association with insurance companies, innovative insurance products at affordable cost, covering life disability and health cover. SHGs and MFIs are also being used extensively for financial inclusion on the credit side.

7.55 The list of eligible sectors for treatment as ‘priority sector’ was expanded in the post-reform period to include investments in specified bonds and also activities such as venture capital. As a result, there was a growing perception of inadequate flow of credit to the traditionally preferred sub-sectors of the priority sector such as agriculture and small industries. In order to address these concerns, revised guidelines on the priority sector were issued in April 2007. Consequently, the priority sector is now restricted to advances to highly employment intensive sectors such as agriculture, small enterprises, retail trade, educational loans, micro-finance and low cost housing.

7.56 Given the low credit-deposit ratios in some States, it became necessary to identify unique problems in such lagging States for expanding banking facilities and formulating area-specific action plans for accelerated financial deepening. Such plans were drawn up with full participation of the State Governments, banks and other local developmental agencies in States such as Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Bihar, Andaman & Nicobar Islands and the North-Eastern States.

7.57 A growing component of inclusive banking is the lending by MFIs that are societies, trusts, cooperatives or ‘not for profit’ companies or non-banking financial companies registered with the Reserve Bank. The MFIs currently cover 8.3 million borrowers. The NBFC segment within this sector accounts for 42.8 per cent of the borrowers and is the fastest growing segment. Interest rates on lending to MFIs/NBFCs have been completely deregulated. Bank lending to such entities for micro-finance is treated as priority sector lending. Private sector and foreign banks are observed to be actively supporting this sector, which is also attracting private equity funding and philanthropy funding from outside the country (Thorat, 2008).

7.58 In India, there have been several innovative experiments with various variants of micro-finance taking into account the highly localised needs. An interesting example in this regard has been the efforts by Aryavart Gramin Bank which embarked upon a novel idea of financial inclusion in remote villages and hamlets of Uttar Pradesh (Box VII.4).

Box VII.4 Financial Inclusion: Novel Method of Financing

The Aryavart Gramin Bank embarked on a novel idea of financial inclusion in remote villages and hamlets of Uttar Pradesh where electricity supply was not available or if available was erratic. The villagers were dependent only on kerosene lamps for their lighting needs and often kerosene had to be bought from black markets, which was affecting their incomes. The bank embarked upon the novel idea of providing solar energy lights to the villages and identified a solar company in India, Tata BP Solar, for providing ‘Solar Home Lighting System’ for the village homes. The company and the dealer were ready to sacrifice their margins as the bank was agreeing to finance the system on a large scale. The system cost Rs.13,000 and consisted of a ready-to-use kit containing a 35 watt solar panel, low maintenance battery, MCR charge controller and two luminaries. The system could light two CFLs of 14 watt for more than 7 hours and could also support one mobile charger, one table fan and a television. The bank extended finance of around Rs.10,000 with Rs.3,000 as margin money to be contributed by the beneficiary. The amount together with interest was to be repaid in 60 equated monthly instalments of approximately Rs.222 per month. This was much less than the amount that the villagers had to spend for their kerosene requirements per month.

The bank had identified literate village youths as business facilitators who were trained by the company for maintenance of the systems. The bank is paying an honorarium of Rs.10,000 per annum to the business facilitators for maintaining 100 such systems. More than 1,300 households in Unnao District and about 500 houses in Barabanki District, were provided with Solar Home Lighting Systems by the bank as at end-December 2007. The bank aims to cover 25,000 households by October 2008.

Source: Website of Aryavart Grameen Bank; http://aryavart-rrb.com.

7.59 Another innovative micro-finance experiment was undertaken by the Mann Deshi Mahila Bank in the Satara District of Maharashtra which works towards the holistic development of women entrepreneurs into women business owners and bank customers (Box VII.5).

Box VII.5 Financial Inclusion: Women Empowerment

The Mann Deshi Mahila Bank, based in Mhaswad, in Satara District, Maharashtra, is an organisation that works towards the holistic development of women entrepreneurs into women business owners’ and bank customers. Founded in 1997, by Chetna Vijay Sinha, the Mann Deshi Mahila Bank has created 17,000 women entrepreneurs. The regulated co-operative that received an “A” grade from District Cooperative Department in 2000, equips its clients with liquid assets which help financial empowerment that, in turn, enables women to become entrepreneurs and plan a stable future for their families. Services which the bank offers include savings, loans, insurance and pensions. A partnership with UTI Mutual Fund had enabled the bank to be the first to offer pension schemes to its clients in Maharashtra.

The bank’s success led to the creation of several sub-organisations, one of which is the Mann Deshi Business School for Rural Women. Set up in partnership with HSBC Bank, the school primarily aims at making its range of courses accessible to women who, due to financial and cultural constraints, would be unable to access such training in neighbouring urban hubs. Unlike traditional business schools that delve into the theor y of microeconomics, accounting, organisational behaviour and so on, this business school focusses on imparting simple business skills. The school’s courses can be categorised into basic business-oriented courses, such as financial literacy, marketing and product development and entrepreneurial or skill-based courses. The business school in Vaduj, Mhaswad attracts women from the surrounding villages as well as larger towns. As most of the women who attend the school are part of larger joint families, the school’s courses are designed so as to enable them to attend the school after completing their household chores and supplement their household income with their earnings.

In 2007, in partnership with the Deshpande Foundation, which supports innovation and entrepreneurship in India, Mann Deshi and Mann Vikas (the NGO wings of the bank) established the Business School on Wheels for Rural Women. This currently operates in the Hubli-Dharwad district in the neighbouring State of Karnataka. A specially designed bus travels the district and offers courses similar to those of the business school. What is striking about the Mann Deshi Business School and the Business School on Wheels is that all their courses are designed not just to teach skills, but also at a larger level, to cater to the needs of the society. By enforcing a strict no educational qualification, no age bar policy, and with fees ranging from Rs.180 to Rs.1,800, the school has been able to attract, during the last year, 650 women from all social backgrounds and capacities, and provide them with skills they otherwise would never have been able to acquire.

Reference:

Creado, J. and R. Koshi. 2008. Creating Leaders at the Bottom of Pyramid, Microfinance Insight, March.

7.60 Micro-finance has emerged as a major mode of expanding outreach of the formal financial sector in a number of countries. The experiences of these countries provide useful inputs regarding the methodology and model of finance to be emulated in other counties (Box VII.6).

7.61 The Grameen system has been widely replicated by micro-finance organisations in several other countries, including some institutions in India. For instance, Activists for Social Alternatives(ASA), Tiruchirapalli (Tamil Nadu) provides a range of integrated financial andnon-financial services through its Gram Vidiyal (GV) programme. The GV consists of a federated structure built upon Grameen style small groups throughwhich financial and non-financial services are provided by ASA, a NGO/MFI (Tankha, 2002).

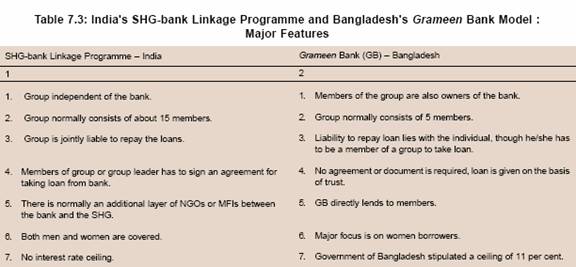

7.62 Though a variety of micro-finance models are followed in India, SHG-bank linkage programme is the predominant one. The model has broad similarities with the Grameen Bank model such as formation of groups, extending credit to poor people, and focus on capacity building. There are, however, certain differences in the methodology followed by SHG-bank linkages programme in India and that by Grameen Bank in Bangladesh (Table 7.3).

7.63 The Reserve Bank has been encouraging the use of IT solutions by banks for enhancing their outreach with the help of their BCs or otherwise. Certain banks have adopted technological solution (Box VII.7). Pilot studies have also been carried out in a few States. One of the technological solutions used is hand-held devices, which are essentially smart card readers. These devices are used for making payments to rural customers and receiving cash from them at their doorsteps. Mobile phones have also been developed to serve as card readers. Account holders are issued smart cards, which have their photographs and finger impressions.

Box VII.6 Grameen Bank in Bangladesh

The Grameen Bank (GB) was launched as a project in a village of Bangladesh in 1976 to assist the poor families by providing credit to help them overcome poverty. In 1983, it was transformed into a formal bank under a special law passed for its creation. It is owned by the poor borrowers of the bank who are mostly women. GB has reversed conventional banking practice by obviating the need for collateral. It has created a banking system based on mutual trust, accountability, participation and creativity. GB provides credit to the poorest of the poor in rural Bangladesh, without any collateral.

As GB was initiated as a challenge to the conventional banking, it rejected the basic methodology of the conventional banking and created its own methodology. The most distinctive feature of Grameen credit is that it is not based on any collateral, or legally enforceable contracts. It is based on ‘trust’ and not on legal procedures and system. It offers credit for creating self-employment, income-generating activities and housing for the poor, as opposed to consumption. It provides service at the doorstep of the poor based on the principle that the people should not go to the bank, bank should go to the people. In order to obtain loans, a borrower must join a group of borrowers. Although each borrower must belong to a five-member group, the group is not required to give any guarantee for a loan to its member. The repayment responsibility solely rests on the individual borrower, while the group and the centre/branch oversee that everyone behaves in a responsible way and none gets into repayment problem. There is no form of joint liability, i.e., group members are not responsible to pay on behalf of a defaulting member. Loans can be received in a continuous sequence. New loan becomes available to a borrower if her previous loan is repaid. All loans are to be paid back in instalments (weekly or bi-weekly).

The GB initially focussed on providing credit facilities and paid little attention to voluntary deposit mobilisation. This policy was changed in 2000, with increased emphasis on deposit mobilisation. GB currently offers four kinds of savings, namely personal savings account, special savings account, Grameen Pension Savings and credit-life insurance savings fund. After operating group lending for 25 years, the GB switched to individual lending recognising that with repeated loan cycles and greater credit exposure, homogeneity of the group would weaken as loan requirements vary with variation in the levels of upliftment attained. Thus, the more flexible Grameen II is more appropriate for reaching the poor because its products can be conveniently used for everyday money management as well as for microenterprises. GB II dispensed with the general loans, seasonal loans, family loans, and more than a dozen other types of loans. It also gave up the group fund; the branch-wise and zone-wise loan ceiling; fixed size weekly instalment; the rule to borrow for one whole year, even when the borrower needed the loan only for three months.

The Government of Bangladesh has fixed interest rate for government-run microcredit programmes at 11 per cent at flat rate, which amounts to about 22 per cent on a declining basis. The interest rate charged by the Grameen Bank is lower than that fixed by the Government of Bangladesh. There are four interest rates for loans from Grameen Bank: 20 per cent (declining basis) for income generating loans, 8 per cent for housing loans, 5 per cent for student loans, and 0 per cent (interest-free) loans for struggling members (beggars). All interests are simple interest, calculated on declining balance method. This implies an annual interest rate of 10 per cent for income-generating loan which is less than that (11 per cent) fixed by the Government of Bangladesh. GB offers attractive rates for deposits ranging from 8.5 per cent to 12 per cent.

As of March, 2008, it had 7.46 million borrowers, 97 per cent of whom were women. With 2,504 branches, GB provides services in 81,574 villages, covering more than 97 per cent of the total villages in Bangladesh.

Source: Website of Grameen Bank; www.grameen-info.org.

7.64 Recognising the potential of emerging business opportunities, some banks have also adopted innovative methods and appropriate technology to provide banking services to financially excluded people by enabling them to overcome obstacles such as procedural problems and difficulties in physical access. For instance, Corporation Bank has implemented the branchless banking model in the States of Goa, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh (Box VII.8).

7.65 To overcome financial exclusion which is widespread in urban areas, Indian Bank successfully experimented with an innovative model of providing access to slum dwellers in Mumbai (Box VII.9).

7.66 Housing to people with moderate income levels is internationally considered to promote financial inclusion (Box VII.10). In India, housing for the poor is one of the six elements of Bharat Nirman programme (announced in the Union Budget 2005-06) and is implemented through the Indira Awas Yojana (IAY). Against a target of 6.0 million houses, 4.11 million houses were constructed up to December 2007 and the cumulative number was expected to go up to 5.18 million houses by end-March 2008.4 Recognising the high cost of construction, the Union Budget 2008-09 proposed to enhance the subsidy per unit in respect of new houses sanctioned after April 1, 2008 from Rs.25,000 to Rs.35,000 in plain areas and from Rs.27,500 to Rs.38,500 in hill/difficult areas. The subsidy for upgradation of houses would be increased from Rs.12,500 per unit to Rs.15,000. In the Union Budget 2008-09, it was also indicated that financial inclusion can be taken forward by expanding the reach, inter alia, of the National Housing Bank (NHB). In order to increase the resource base of NHB, it was proposed to tap the resources of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) to the extent that they fall short of their obligation to lend to the priority sector. It was also proposed to create a fund of Rs.1,200 crore with NHB to enhance its refinance operations in the rural housing sector. The fund would be governed by the general guidelines that are now applicable to the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) with some modifications. The Reserve Bank, in February 2008, advised banks that the members of SC/STs satisfying the income criteria of the DRI scheme for weaker sections of the community can also avail of housing loan up to Rs.20,000 per beneficiary at a concessional interest rate of 4 per cent.5 Following the announcement made in the Union Budget 2008-09, the Reserve Bank in July 2008, advised public sector banks (PSBs) that the Government would provide interest subvention of 2 per cent to PSBs in respect of short-term production credit up to Rs.3 lakh extended to farmers at 7 per cent per annum.

Box VII.7 Successful Model for Financial Inclusion: A Case Study of Andhra Pradesh

The Rural Development Department of Government of Andhra Pradesh launched a pilot project in six Mandals of Warangal District for payment of Social Security Pensions (SSP) and National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) benefits to the beneficiaries. The pilot programme involved six banks viz., State Bank of India, Union Bank of India, State Bank of Hyderabad, Andhra Bank, A.P.Grameena Vikas Bank and Axis Bank. The benefits are paid to the villagers by the business correspondents of banks at the habitation level in the villages. The Rural Development Department, Government of Andhra Pradesh, played a very active role in the project and has financed a major portion of the cost of the cards and the devices. The project was coordinated by the Reserve Bank with the Regional Director, Hyderabad being the Convenor of the Steering Group for the project. The Institute for Development and Research in Banking Technology (IDRBT) was given the role of providing the management information systems (MIS) to the Government in the required format. In the second phase, the project will be scaled up to 50,000 villagers. The State proposes to scale up the efforts to the entire State in due course. The Andhra Pradesh Government also proposes to issue smart cards to all the SHG members in the State.

The project involves payment of SSP and NREGS benefits through BCs with the use of smart card and mobile technology. The BC uses a fingerprint scanner cum identifier, a mobile and a printer to process the payments. The beneficiaries hold smart cards with their photographs and images of their fingerprints pre-loaded at the time of their enrolment. The photograph and fingerprint are used for identification and authentication of the beneficiary. Once authenticated, the radio frequency identification device (RFID) chip embedded in the card gets charged. When the card with charged chip is brought close to the mobile phone, message templates for deposit, withdrawal and balance enquiry are generated in the mobile. The BC needs to select the relevant option and feed the amount of transaction through the mobile keypads and send the message to the back-end server. The server authenticates the message, processes the transaction and sends an update back to the mobile, which, in turn, writes back to the card. When the card is brought close to the printer, transaction report is printed in triplicate. The BC carries cash physically for making payments to the beneficiary. Thus, in effect, each BC carries a pocket ATM to the village in which it operates. The technology holds potential for whole range of activities that banks can conduct through BCs and this includes other products like fixed deposits, various loans, insurance, among others. The mobiles connect to a central data base server of the banks. The application has an off-line model also, which enables its operation in remote areas where there is no connectivity. Presently, the SSP and NREGS benefits are being paid through post offices which are given a commission of 2 per cent.

The State Government, for the initial pilot covering six mandals, agreed to pay Rs.90 per smart card, Rs.10,000 per hand held device and 2 per cent commission on transactions. The Government agreed to meet a part of the infrastructure costs to kick start the project. For the scaled up project, it is expected that the 2 per cent commission on turnover will be maintained and banks will fund the infrastructure. However, the model may have to be different in States with lesser turnover, as fixed cost per village is almost the same. The banks pay Rs.1,000 to the village organisation member in the village who is the representative of the BC of the bank. The cost of cards is a one-time exercise and enrolment of beneficiaries also involves an expense of Rs.50 per person in addition to the card cost.

The advantages to the bank are that the cost of transactions is reduced and there is scope for other services like crop loans, access to cheap savings in villages and micro-insurance, among others. The State Government can make all its payments through this mechanism. This would include salaries, pensions and contractor payments. The model ensures cost savings in the payment delivery mechanism and payments can be made centrally from the district or the State headquarters. An added benefit is that several bogus beneficiaries have been weeded out because of bio-metric identification and the State Government is expecting to save substantial amount on that account.

The model adopted for the project involves selection of technology and technology vendor by the bank; appointment of a BC; finalising the operating procedures with respect to transactions entered between bank and BCs such as movement of cash, crediting beneficiary accounts, payment of fee/commission and control mechanism. Other aspects of the model are enrolment and collection of critical data about the beneficiaries and issue of cards to them, training and sensitising the beneficiaries and meeting operational needs through ongoing support in servicing of instruments, constant monitoring and periodic evaluation of the project for improvement.

Box VII.8 Branchless Banking through Business Correspondents

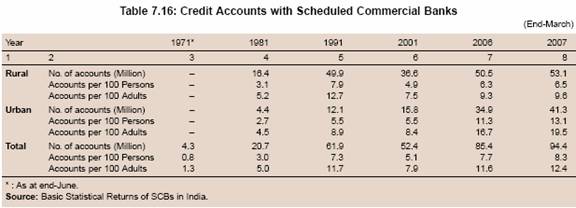

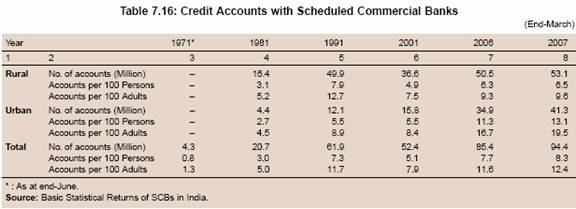

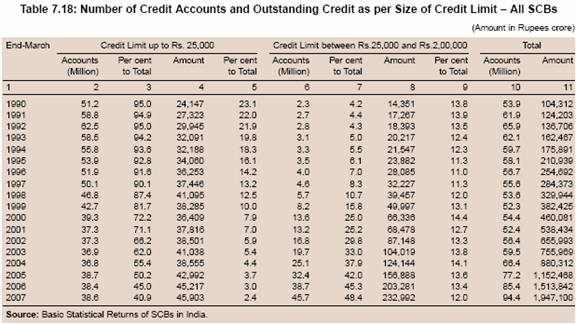

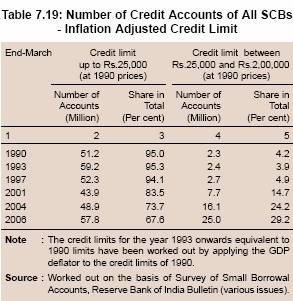

Corporation Bank has taken up an outreach programme through the use of technology in order to provide very simple and basic financial services to the poor and the disadvantaged in the rural areas. To accomplish the task, the bank conducted a survey in the identified villages to gather information regarding the structure and size of village, family/household details such as occupation, asset ownership and the use of financial services. The automation of the survey facilitated generation of Corp Pragathi Savings Bank (CPSB) Account opening forms along with the photograph of the user at the site for the family members who expressed their desire to open an account with the bank.