|

Abstract:

This study assesses the recent credit dynamics and export performance of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). Demonetisation led to a further decline in the already decelerating credit growth of the MSME sector, while GST implementation does not seem to have had a significant impact on overall credit to MSMEs. The growth in credit to MSMEs has recovered since the lows of late 2017 to reach the mid-2015 level. Micro credit to MSMEs, including loans by banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), shows a particularly healthy rate of growth in recent quarters. In contrast to credit growth, MSME exports appear to be affected more by GST implementation vis-à-vis demonetisation.

I. Introduction

Globally, the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) segment plays a crucial role in employment generation and contributes significantly to overall economic activity. In India, the MSME sector constitutes a vast network of over 63 million units and employs around 111 million people. The share of MSMEs in overall GDP is around 30 per cent (GOI, 2018). The MSME sector accounts for about 45 per cent of manufacturing output and around 40 per cent of total exports of the country. However, the sector faces operational problems due to its size and nature of business, and is, therefore, relatively more susceptible to various shocks to the economy. MSMEs largely operate in the informal sector and comprise a large number of micro enterprises and daily wage earners.

The MSME sector has witnessed two major recent shocks, viz., demonetisation and introduction of goods and services tax (GST). For instance, contractual labour in both the wearing apparel and gems and jewellery sectors reportedly suffered as payments from employers became constrained after demonetisation (RBI, 2017). Similarly, the introduction of GST led to increase in compliance costs and other operating costs for MSMEs as most of them were brought into the tax net. In a recent survey conducted by SMERA Ratings Ltd. (SMERA, 2017), more than 60 per cent of respondents felt that their systems were not ready for the new tax regime. A study by Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) indicates that post-demonetisation and post-GST introduction, the relative credit exposure initially declined for most MSMEs but had recovered fully by March 2018 (SIDBI 2018a, SIDBI 2018b). During demonetisation, many smaller districts, which were witnessing higher growth, felt greater shock compared to larger centres.

Sectors such as manufacturing and construction were reportedly most affected by implementation of GST and demonetisation; however, both these sectors are showing signs of improvement (World Bank, 2018). Demonetisation and GST are expected to be positive in the long run with growth in digitisation, enhanced ease of doing business and creation of database of transactions which would facilitate better access to finance and improve the medium- and long-term growth prospects of the sector. These structural reforms, however, might have disrupted the performance of MSMEs in the short run. In the above backdrop, this study empirically examines how credit and exports of the MSME sector have fared in the wake of the recent shocks.

II. Credit

Despite significant contribution to economic growth, MSMEs face several bottlenecks inhibiting them from achieving their full potential. A major obstacle for the growth of MSMEs is their inability to access timely and adequate finance as most of them are in niche segments where credit appraisal is a major challenge. According to International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimates, the potential demand for India’s MSME finance is about US$ 370 billion as against the current credit supply of US$ 139 billion, resulting in a finance gap of US$ 230 billion (equivalent to 11 per cent of GDP) in comparison to a finance gap of US$ 5.2 trillion (19 per cent of GDP) for the group of developing countries (IFC, 2017a; 2017b).

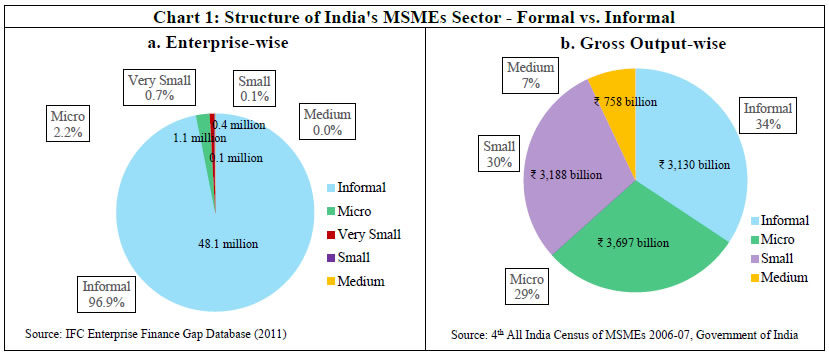

As noted earlier, MSMEs face constraints in accessing credit through formal channels because of their nature of operations. About 97 per cent of MSMEs operate in the informal sector (Chart 1).1 In value terms, the share of informal sector in gross output of MSMEs is about 34 per cent. As per National Accounts Statistics 2012, the share of informal (unregistered) sector manufacturing MSMEs in total GDP is estimated at around 5 per cent. A large number of these firms depend on informal channels because of easy accessibility and availability of credit without any documentation hassles and mortgages, even though the rate of interest on such loans may be very high. The challenges faced by MSMEs in accessing finance are due to lack of comprehensive formal documentation relating to accounts, income and business transactions. As a result, loans are provided to the MSMEs mainly through appraisal of their collaterals rather than assessing their true business potentials (Ayadi and Gadi, 2013). Further, banks do not trust start-ups, view such loans as risky and thus do not prefer extending finance to MSMEs (Biswas, 2014).2 All these observations suggest that there could be potentially large long-run benefits from formalisation of MSMEs.

II.1 Evolution of MSME Credit

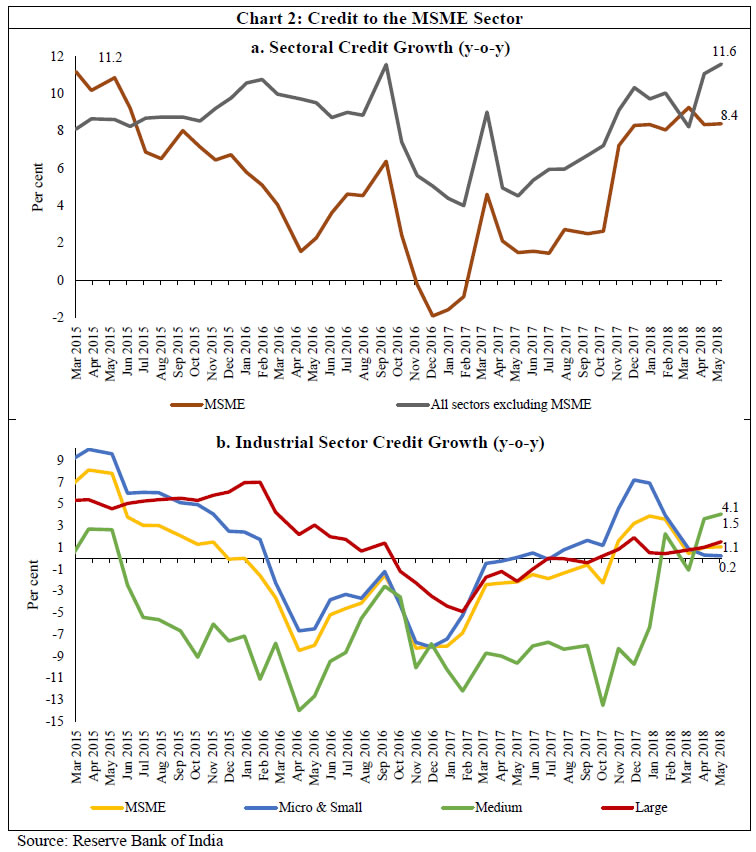

The year-on-year (y-o-y) growth of bank credit to the MSME sector decelerated gradually during 2015 to 1.6 per cent in April 2016 before exhibiting some recovery till October 2016 (Chart 2a). The deceleration in credit growth during 2014-16 was partly due to overall slowdown in economic activity, rising non-performing assets (NPAs) and reclassification of food and agro-processing units from MSME category to agriculture sector (as per the revised priority sector lending guidelines, issued to banks in April 2015). Credit growth fell significantly and turned negative during November 2016-February 2017. Therefore, it seems that demonetisation accentuated the slowdown in credit growth, particularly to industrial sector (Chart 2b). However, the growth in credit to the MSME sector recovered after February 2017 to reach an average of 8.5 per cent during January-May 2018. This slowdown in bank credit to MSMEs beginning late 2016 and its recovery since mid-2017 broadly mirrors the trends in overall bank credit. Furthermore, micro-credit i.e., small loans amounting to less than ₹ 10 lakhs (including credit by banks, non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and others), fell the most during demonetisation but has been growing rapidly since September 2017 (Chart 3).

Within the formal financial sector, MSMEs receive loans mainly from banks (around 90 per cent). The share of credit provided by banks has declined since September 2016 partly reflecting the risk aversion of banks due to deterioration in their asset quality (Chart 4). In contrast, loans extended by NBFCs to MSMEs grew strongly at an annual average rate of 35 per cent during the same period and their share in total credit almost doubled from around 5.5 per cent in December 2015 to around 10 per cent by March 2018. Lower NPAs of NBFCs in MSME credit as compared to banks might have helped them in extending credit to the sector.

The share of credit extended to MSMEs in overall bank credit declined steadily to around 14 per cent by end-March 2018 from about 17 per cent in 2007; this could partly be due to over-lending to large corporates (now stressed) in the second half of 2000s. Additionally, within the credit to industrial sector, the share of credit to medium enterprises has dropped significantly as compared to the share of micro and small enterprises (Chart 5a). While the share of public sector banks (PSBs) in overall bank credit has fallen since 2015, it has increased for private sector banks (PVBs) (Chart 5b).

NPAs of both PSBs and PVBs pertaining to the MSME sector have increased over time, with the level being much higher in the case of PSBs (Chart 6). Despite rise in NPAs, credit to MSMEs by PSBs recovered in the second half of 2017-18. As against this, the growth in credit to MSMEs by PVBs decelerated during this period, although credit growth of PVBs remains higher than that of PSBs. Also, NPAs related to industrial sector MSMEs were higher compared to that of the services sector and the overall NPA level of the banking sector. Thus, asset quality deterioration might also have impacted the supply of bank credit, especially to MSMEs.

II.2 What explains the evolution of MSME credit by banks?

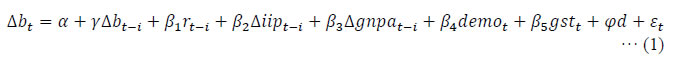

Taking into account both demand and supply side factors as suggested in literature [see Kashyap and Stein (1995); Ehrmann et al. (2001); Farinha and Margues (2001) and Khundrakpam (2011)] and augmenting with asset quality variable, the following reduced form equation has been used to assess the possible effects of demonetisation and GST on bank credit to the MSME sector:

where b is (log) real bank credit, r is real policy interest rate, iip is (log) industrial production and gnpa is gross NPA ratio (as percentage of total advances). demo and gst are dummy variables for demonetisation (takes value 1 for 2016-17:Q3 and zero otherwise) and GST (takes value 1 for 2017-18:Q2 and 2017-18:Q3 and zero otherwise), respectively. Other dummy variables ‘d’ have been used to capture the impact of the global financial crisis in 2009 and a few temporary spikes in credit growth. ∆ stands for first difference. Real bank credit is calculated by deflating nominal bank credit with consumer price index (CPI), whereas 6-month moving average of year-on-year CPI inflation is deducted from nominal policy rate to derive the real policy rate. To examine further as to whether the determinants of bank credit differ between the MSMEs and non-MSMEs, two variants of the above equation are estimated: one, using credit to MSME sector; and second using credit to sectors excluding MSME (i.e., non-MSME sector). Quarterly data for 2006-07:Q4 through 2017-18:Q3 are used and the variables, viz., credit, industrial production and CPI are adjusted for seasonality using Census X-13 methodology.

| Table 1: Determinants of Bank Credit Growth: All Banks |

| |

MSME |

Non-MSME |

| Variable |

Coeff. |

t-Stat |

Coeff. |

t-Stat |

| Constant |

1.25** |

(2.35) |

0.60*** |

(2.78) |

| Δbt-3 |

0.06 |

(0.57) |

0.36*** |

(4.65) |

| rt-1 |

-0.13** |

-(2.21) |

-0.07* |

-(1.67) |

| Δiipt-3 |

0.28** |

(2.37) |

0.41*** |

(5.95) |

| Δgnpat-1 |

-0.01** |

-(2.31) |

-0.01* |

-(1.74) |

| demot |

-3.23*** |

-(9.56) |

-1.11*** |

-(4.04) |

| gstt |

0.36 |

(0.51) |

0.49* |

(1.89) |

| d2009Q1 |

|

|

-3.38*** |

-(10.96) |

| d2009Q2 |

4.11*** |

(8.68) |

-2.30*** |

-(8.79) |

| d2011Q1 |

-5.85*** |

-(13.77) |

|

|

| d2014Q1 |

4.46*** |

(11.32) |

|

|

| R2 |

0.75 |

|

0.44 |

|

| LM –serial corr. (4) |

0.70 |

|

0.78 |

|

| ARCH (4) |

0.41 |

|

0.42 |

|

***, **, *: significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

Figures with respect to serial correlation LM tests and ARCH tests are p-values (numbers in brackets are lags selected for the test).

Source: Authors’ estimates. |

Regression estimates suggest that tighter monetary policy has a dampening effect on credit growth and vice versa (Table 1). In the short-run, i.e., with one quarter lag, an increase of 100 basis points (bps) in the policy rate could lead to a reduction in credit growth of the MSME and non-MSME sectors by 13 bps and 7 bps, respectively. The results also indicate adverse effects of deterioration in asset quality of the banking system on credit growth. The demonetisation dummy is found to be statistically significant, suggesting a contractionary effect on credit growth after demonetisation as also evident in the descriptive analysis (Section II.1). However, the effect of GST on credit growth of the MSME sector was found to be statistically insignificant.3,4

Regression estimates are also presented for Equation (1) using credit extended to MSMEs by public sector banks and private banks separately (Table 2). The results suggest that the effect of interest rates on credit growth is on the expected lines in case of public sector banks while the effect is found to be statistically insignificant in case of private banks. The coefficient of GNPA ratio is statistically insignificant for private banks, which implies that asset quality may not be a major concern for them, given their low NPAs. However, asset quality impacts the credit growth of public sector banks adversely. The adverse effect of demonetisation on credit to MSMEs is statistically significant for public sector banks and insignificant for private banks. These results point to the possibility that impaired balance sheets of public sector banks accentuated the effect of demonetisation on their credit growth. In contrast, strong balance sheets of private banks kept their MSME credit extension immune to the demonetisation shock.

| Table 2: Determinants of MSME Credit Growth: Bank Group-wise |

| |

Public Sector Banks |

Private Banks |

| Variable |

Coeff. |

t-Stat |

Coeff. |

t-Stat |

| Constant |

0.57 |

(0.85) |

1.11 |

(1.23) |

| Δbt-2 |

|

|

0.33** |

(2.58) |

| Δbt-3 |

0.27* |

(1.76) |

|

|

| rt-2 |

-0.16* |

-(1.80) |

-0.24 |

-(1.62) |

| Δiipt-1 |

0.35* |

(1.83) |

0.58** |

(2.25) |

| Δgnpat-1 |

-0.01* |

-(1.70) |

0.01 |

(0.54) |

| demot |

-3.39*** |

-(5.29) |

-0.37 |

-(0.55) |

| gstt |

2.57** |

(2.45) |

-0.40 |

-(0.36) |

| d2009Q1 |

4.84*** |

(6.48) |

|

|

| d2009Q2 |

-6.56*** |

-(12.00) |

|

|

| d2011Q1 |

4.52*** |

(8.62) |

|

|

| d2008Q4 |

|

|

-7.32** |

-(7.23) |

| R2 |

0.65 |

|

0.44 |

|

| LM –serial corr. (4) |

0.66 |

|

0.81 |

|

| ARCH(4) |

0.05 |

|

0.37 |

|

***, **, *: significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

Figures with respect to serial correlation LM tests and ARCH tests are p-values (numbers in brackets are lags selected for the test).

Source: Authors’ estimates. |

II.3 Reserve Bank measures to support MSME credit

Given the difficulties faced by MSMEs in debt repayments after demonetisation, the Reserve Bank announced a series of measures to provide some relief. The prudential norms were relaxed (on November 21, 2016) by providing an additional 60 days for repayment of dues, beyond what is applicable for loans to be considered as sub-standard for running working capital account, for accounts with sanctioned limit of ₹ 1 crore or less. The relaxation was extended (on December 28, 2016) by providing additional 30 days for repayment of dues. On December 29, 2016, the RBI advised banks to use the facility of providing ‘additional working capital limit’ to their MSME borrowers to overcome the cash flow mismatches. This was a one-time measure valid up to March 31, 2017.

Recognising the potential gains from transition of MSMEs to the formal sector, the Reserve Bank announced relief measures for GST-registered MSMEs with aggregate exposure of less than ₹ 250 million (as on January 31, 2018), which were standard as on August 31, 2017. Loans of such borrowers were to be declared NPA only if the dues (outstanding as on September 1, 2017 and payments due between September 1, 2017 and January 31, 2018) to the banks/NBFCs were more than 180 days past original repayment date. The measure is expected to have provided respite to 0.14 million borrowers whose accounts were standard in August 2017 but would have become NPA in January 2018. This is also estimated to have reduced the gross NPA amount of the banks by ₹ 129 billion (SIDBI, 2018).

Further, having regard to the input credit linkages and ancillary affiliations and to encourage formalisation of the MSME sector, the Reserve Bank in its developmental and regulatory policies of June 2018, temporarily allowed banks and NBFCs to classify their exposure as per the 180 days past due criterion, to all MSMEs, including those not registered under GST, as a ‘standard asset’. From January 1, 2019 onwards, the 180-day past due criterion in respect of dues payable by GST registered MSMEs would be aligned to the extant norm of 90-day past due criterion in a phased manner, whereas for entities that do not get registered under the GST by December 31, 2018, the asset classification in respect of dues payable from January 1, 2019 onwards would immediately revert to the 90-day norm. In February 2018, RBI also announced to remove the credit cap for loans between ₹ 50 million and ₹ 100 million for MSME services sector borrowers for consideration under priority sector.

III. Exports

The MSME sector contributes around 40 per cent to India’s total exports (GOI, 2018). Recognising significant contribution of MSMEs, the Government has put in place several measures in its Foreign Trade Policy (FTP) to promote exports by MSMEs. The Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) was introduced in the FTP 2015-20 effective April 1, 2015 with the objective to offset infrastructural inefficiencies and associated costs involved in exporting goods that are produced in India, including those by MSMEs. Other schemes offered by the FTP to MSMEs include: (i) interest subvention of 3 per cent for pre-and post-shipment Rupee Export Credit with effect from April 1, 2015 for five years; (ii) duty credit scrips at the rate of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 per cent of the FOB value of exported goods under MEIS scheme; (iii) by achieving a certain threshold level of exports, exporters are provided ‘Status Recognition Certificate’, which entitles them for certain privileges like faster clearance of goods by customs and provision for free cost of exports and exemption from furnishing Bank Guarantee under the Export Promotion Schemes; and, (iv) training/counselling under Niryat Bandhu Scheme.5

Among various items of MSMEs exports, gems and jewellery, carpets, textile, leather, handlooms and handicrafts items are highly labour intensive and depend heavily on cash for working capital requirements and payment towards contractual labourers. Hence, export shipments of these sectors could have been impacted by demonetisation. Karigoleshwar (2017) found that export shipments of gems and jewellery, readymade garments, meat and dairy products, handicrafts and carpets registered a decline or lower growth in November 2016 compared to October 2016. A quick survey by Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) in December 2016 indicated a sharp decline in arrivals of animal hide in major leather clusters. In view of constraints on availability of raw material as well as transportation and labour bottlenecks, about 60 out of 100 respondents indicated that they were no longer taking export orders.

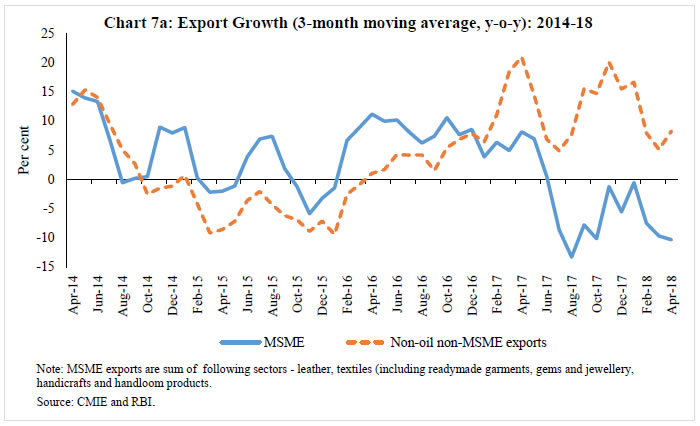

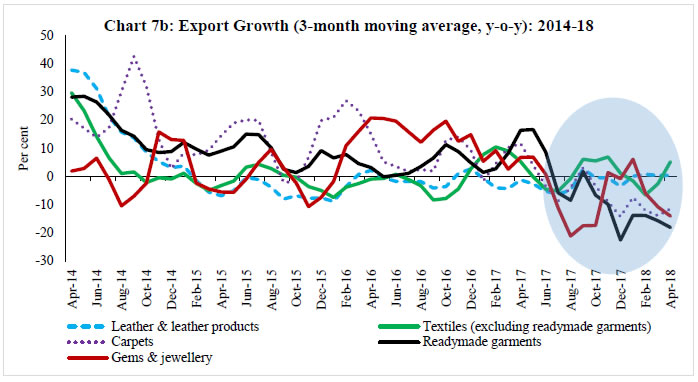

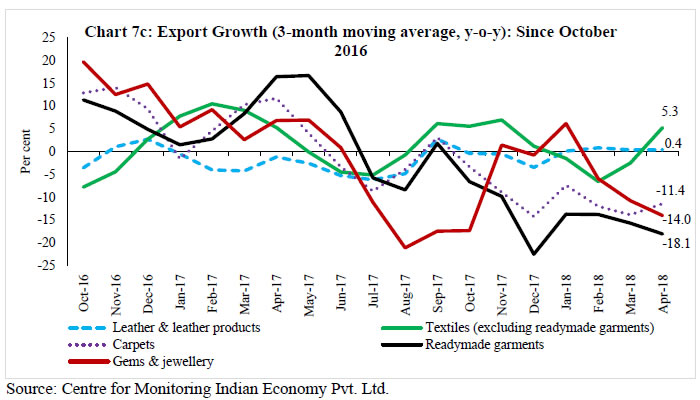

MSME exports showed only mild weakness post October 2016 (demonetisation period) but decelerated sharply during April and August 2017 (GST implementation period) with only a temporary recovery during the post-GST implementation period. In contrast, non-oil non-MSME exports growth showed healthy growth post demonetisation but also suffered a dip during April-July 2017 (Chart 7a). Even at sectoral level, MSME-dominated export items appear to have been impacted more adversely by GST than by demonetisation (Charts 7b and 7c). According to a survey (October 2017) by SMERA, the first phase of GST implementation and delays in the refund of the upfront GST hit the exporters in the MSME segment hard as they are largely dependent on daily cash flows for their working capital. This is also corroborated by empirical analysis in Tomar et al. (2018). Sharp rise in imports along with fall in production of these sectors supports the evidence of supply chain disruptions due to GST implementation rather than the weak demand conditions per se.

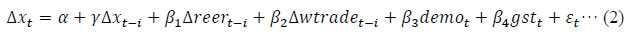

In order to formally assess the possible impact of demonetisation and GST implementation on MSMEs’ exports, the following reduced-form equation incorporating both demand and supply side determinants of exports is estimated (using monthly seasonally adjusted data for the period April 2011 through November 2017):

where x is real exports by MSMEs, reer is 36-currency trade weighted real effective exchange rate, and wtrade is world trade volume. demo is demonetisation dummy that takes value 1 for December 2016 and January 2017 and zero otherwise. gst is GST dummy that takes value 1 for July 2017 and zero otherwise.6 ∆ stands for month-on-month growth expressed in percentage terms calculated from the natural log of the respective variable. MSME exports in dollar terms are deflated by unit value index of imports of advanced economies to calculate real exports.7 Like in eq. (1), two variants of the eq. (2) are estimated: one, for MSME exports, and second for non-oil exports excluding MSME exports (i.e., non-MSME exports).

| Table 3: Determinants of Export Growth |

| |

MSME |

Non-MSME |

| Variable |

Coeff. |

t-Stat |

Coeff. |

t-Stat |

Coeff. |

t-Stat |

| Constant |

0.42 |

(0.70) |

0.73 |

(1.19) |

0.16 |

(0.30) |

| Δxt-1 |

-0.75*** |

-(5.94) |

-0.79*** |

-(6.13) |

-0.39*** |

-(5.16) |

| Δxt-2 |

-0.28** |

-(2.50) |

-0.33** |

-(2.77) |

|

|

| reert-2 |

-0.89** |

-(2.29) |

-0.90** |

-(2.21) |

-0.56* |

-(1.69) |

| Δwtradet-4 |

1.87** |

(2.55) |

2.33** |

(2.66) |

|

|

| Δwtradet-6 |

|

|

|

|

1.85** |

(2.45) |

| demot |

|

|

-2.87* |

-(1.97) |

1.97 |

(0.53) |

| gstt |

|

|

-16.29*** |

-(5.62) |

-4.46*** |

-(7.96) |

| R2 |

0.48 |

|

0.53 |

|

0.34 |

|

| LM (8) |

0.49 |

|

0.45 |

|

0.54 |

|

| ARCH(8) |

0.25 |

|

0.87 |

|

0.40 |

|

***, **, *: significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

Figures with respect to serial correlation LM tests and ARCH tests are p-values (numbers in brackets are lags selected for the test).

Source: Authors’ estimates. |

The price and income elasticities of MSME exports and non-MSME exports have correct signs and are statistically significant (Table 3). The short run elasticities of the MSME sector are somewhat higher than the non-MSME sector, while the long run elasticities are broadly comparable. These results suggest that exchange rate and global demand shocks have a relatively larger impact on the MSME sector in the short run, indicating their limited capacity to manage such shocks. For MSMEs, the coefficients of demonetisation dummy and GST dummy are found to be negative and statistically significant, suggesting some impact on their exports from these shocks.8 On the other hand, non-MSME exports appear to have been immune to demonetisation effect but were impacted by GST implementation.

In order to provide support to MSMEs in the context of implementation of GST, a host of measures have been undertaken by the government. Under the mid-term review of the FTP in December 2017, the government decided to provide additional relief worth ₹ 84.5 billion annually for labour-intensive and MSME sectors through measures such as: (i) increasing the rate of incentives under MEIS scheme by 2 per cent for labour intensive MSME sectors, which is additional for ready-made garments and made-ups where incentives were earlier enhanced from 2 per cent to 4 per cent; (ii) increasing incentives under Services Exports from India Scheme (SEIS) for notified service providers by 2 per cent. Further, to reduce the compliance burden of MSMEs, government has allowed businesses with a turnover of up to ₹ 15 million to file returns and pay taxes quarterly (instead of monthly).

While recognising the difficulties of cash blockage on account of having to pay GST/IGST (Integrated GST) upfront on the inputs, raw materials, and finished goods imported or procured for the purpose of exports, the GST Council re-introduced the pre-GST tax exemptions on such imports and introduced a special scheme of payment of GST @ 0.1 per cent on procured goods of exporters in October 2017. A refund of GST/IGST paid on domestic procurement made under Advance Authorisation, Export Promotion Capital Goods (EPCG) and Export Oriented Unit (EOU) schemes was also permitted up to March 31, 2018. An e-Wallet scheme9 was designed to credit notional or virtual currency by the DGFT to facilitate the exporters to make the payment of GST/IGST on the goods imported/procured by them so their funds are not blocked. During its 26th meeting held on March 8, 2018, the GST Council decided to extend the available tax exemptions on imported goods for further six months beyond March 31, 2018.

IV. Conclusion

This study assesses the recent dynamics of bank credit and export growth of MSMEs in the aftermath of demonetisation and GST implementation. The main findings are:

-

Credit growth in the MSME sector had started decelerating even before demonetisation, and declined further during the demonetisation phase. In contrast, GST implementation does not seem to have had any significant impact on credit. Overall, MSME credit and especially micro credit to MSMEs, including loans by banks and NBFCs, shows a healthy rate of growth in recent quarters. During the quarter April-June 2018, bank credit to MSMEs increased on average by 8.5 per cent (y-o-y), mirroring the level of growth during April-June 2015, with credit to micro and small enterprises growing at an even healthier rate.

-

In contrast, MSME exports were affected more adversely by issues relating to GST implementation than demonetisation due to delay in refund of upfront GST and input tax credit affecting cash-driven working capital requirements.

References

Ayadi, R. and Gadi, S. (2013). “Access by MSMEs to Finance in the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean: What Role for Credit Guarantee Schemes?” MEDPRO Technical Report No. 35/April.

Biswas, A. (2014). “Financing Constraints for MSME Sector”, International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies, 1(5), pp. 60-68.

Ehrmann, M., Gambacorta, L., Martinéz Pagés, J., Sevestre, P., and Worms, A. (2001). “Financial Systems and the Role of Monetary Policy Transmission in the Euro Area”, Working Paper Series 105, European Central Bank, December.

Farinha, L. and Carlos, R. M. (2001). “The Bank Lending Channel of Monetary Policy: Identification and Estimation using Portuguese Micro Bank Data”, Working Paper Series 102, European Central Bank.

Government of India (2018). Annual Report 2017-18, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, URL: https://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/MSME-AR-2017-18-Eng.pdf

---- (2011-12a). Final Report: Fourth All India Census of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises 2006-07: Registered Sector, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

---- (2011-12b). Final Report: Fourth All India Census of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises 2006-07: Unregistered Sector, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

International Finance Corporation (2017a). MSME Finance Gap Database.

---- (2017b). MSME Finance Gap: Assessment of the Shortfalls and Opportunities in Financing Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Markets.

Kashyap, A.K. and Stein, J.C. (1995). “The Impact of Monetary Policy on Bank Balance Sheets”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 42, pp.151-195.

Karigoleshwar (2017). “Impact of Demonetisation on MSMEs”, International Research Journal of Management and Commerce, 4(10), pp. 313-318.

Khundrakpam, J.K. (2011). “Credit Channel of Monetary Transmission in India - How Effective and Long is the Lag?”, RBI Working Paper WPS (DEPR): 20/ 2011.

Mundra, S.S. (2017), “Bankers & SME Borrowers – The Emerging Mantras”, Keynote address at the 3rd Bankers Borrowers Business Summit, organized by the ASSOCHAM, New Delhi, June.

Reserve Bank of India (2017). Macroeconomic Impact of Demonetisation- A Preliminary Assessment, March, url: https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/MID10031760E85BDAFEFD497193995BB1B6DBE602.PDF

Small Industries Development Bank of India (2018a). MSME Pulse, March.

--- (2018b). MSME Pulse, June.

SMERA Ratings Ltd. (2017). “Significant relief for Micro and Small Enterprises in GST Structure”, October 6, URL: https://www.smeraratings.in/analysis-msme-gst.htm.

Tomar, S., S. Mathur and S. Ghosh (2018). “Working Capital Constraints and Exports: Evidence from the GST rollout”, Mint Street Memo No. 10, Reserve Bank of India, February.

World Bank (2018). India Development Update: India's Growth Story, World Bank Group, New Delhi, March.

|